6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

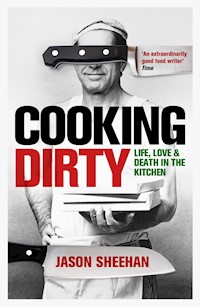

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

From his first job scraping trays at a pizzeria at the age of fifteen, Jason Sheehan has worked at all kinds of restaurants across America, from Buffalo to Tampa to Albuquerque: at a French colonial and an all-night diner, at a crab shack just off the interstate and a fusion restaurant in a former hair salon. In Cooking Dirty he tells the story of one man's addiction to the urgency, stress, and adrenalin of minimum-wage kitchen work. His universe becomes 'a small, steel box filled with knives and meat and fire', where the kitchen is a fraternity with its own rites and initiations: cigarettes in the walk-in freezer, sex in the basement, drugs everywhere. Restaurant cooking sets a series of seemingly endless personal challenges, from the first perfectly done mussel to the satisfaction of surgically sliced foie gras. The kitchen itself is a place in which life's mysteries are thawed, sliced, broiled, barbecued, and fried - a place where people from the margins find their community and their calling. Cooking Dirty is a passionate, funny, electrifying memoir of addiction: an addiction to kitchen work. It reveals the hell and glory of restaurant life, as told by a survivor. Jason Sheehan is his own unforgettable central character - edgy, driven, irresistible. Eating out will never be the same again.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Jason Sheehan won a James Beard Award – America’s top food award – in 2003. His work has appeared in Best American Food Writing every year for the past five years. Cooking Dirty is his first book.

First published in 2009 in the United States of America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 18 West 18th Street, New York, 10011.

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Jason Sheehan, 2009

The moral right of Jason Sheehan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84887 190 8 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 309 3

Designed by Gretchen Achilles Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

FOR EVERY CHEF WHO TRAINED ME, EVERY EDITOR WHO TOLERATED ME, ALL COOKS EVERYWHERE AND MOSTLY FOR MY TWO BEST GIRLS, LAURA VICTORIA AND PARKER FINN: IF THERE’S ANY GOOD IN ME THESE DAYS, IT’S ALL THEIR FAULT.

What matters is what you don’t know. That’s where they’ll get you. —PATTY CALHOUN

No matter where you go, there you are. —BUCKAROO BANZAI

PROLOGUE: FLORIDA, 1998

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

ALMOST FAMOUS

LEARNING CURVE

SEX, DRUGS AND KUNG PAO CHICKEN

WILL WORK NIGHTS

LA MÉTHODE

PREP AND PANTRY

THE WHITE COAT

FNG

PAST IS PROLOGUE

COOK’S HOLIDAY

MAL CARNE

CHICKEN HITLER

COOKING FOR DANNY

BALLROOM BLITZ

BAKED

ATOMIC CHEESEBURGER

COOKING LIVE

WAR STORIES

ON THE OUTSIDE

WHAT MATTERS IS WHAT YOU DON’T KNOW

EPILOGUE: TEN THOUSAND NIGHTS

Acknowledgments

We had this superstition in the kitchen: On Fridays, no one counted heads. No one counted tables at the end of the night, no one counted covers. When the last table was the dupes were just left there, mounded up on the spike. You didn’t look, not even in secret. No one even guessed. Bad things would happen if you did.

And even though no one looked, bad things happened anyway. Lane died on a Friday night due to complications of lifestyle—which is to say, he was shot by an acquaintance in a squabble over twenty dollars’ worth of shitty brown horse. He wasn’t found until Saturday morning; no one thought to call the restaurant to let us know that he wouldn’t be coming in to work that day. He was just considered AWOL—a no-call/no-show that left the line a man short going into the early-bird rush.

This was Tampa, Florida, in the middle nineties—a bad time for cuisine, a worse place. It wasn’t a great time for me, either. Worse for Lane, I guess, but everything is a matter of degrees. Of right and wrong places, right and wrong times.

Eventually, Lane’s name was found in a late edition of the Tampa paper. Or maybe someone saw it on TV. I don’t remember. In any event, we all found out, precisely too fucking late, that Lane was now fry-cooking in the sweet hereafter. The first hit was due in soon. And while there is a lot of voodoo in the air down in Florida, no one wanted to bet heavy on the long odds of Lane coming back as a zombie and retaking his place on the line. He’d been shit as a living cook anyhow. Being newly undead would probably only slow him worse than the smack had.

“This is why cooks should always have the decency to die in a public place,” said Floyd, the kitchen manager and nominal chef. “That way, they make the morning paper and we’d know who isn’t showing up for work.”

In the kitchen, we discussed the best methods for dying in a spectacularly newsworthy fashion,1 and Floyd promoted one of the afternoon prep crew into Lane’s slot on the line. The FNG—the Fucking New Guy—went on fryers. It was my fourth night on the line at Jimmy’s Crab Shack,2 and no longer the F-ingest NG, I was brevetted to grill/steamer, working beside Sturgis, who was grill/top.

Saturday night, early, no one was able to find a rhythm. We kept getting popped, then stalled, taking five tables like BangBangBangBangBang, then nothing for ten minutes. The FNG fell into the weeds—dans la merde even at this stuttering half-speed. Jimmy, the owner, was antsy on expo, alternating between giggling fits and bouts of screaming obscenity. Floyd rotated the line out for cigarettes. He had a speed pourer filled with rum and hurricane mix in his rack that he sucked at like a baby with a bottle, and he jumped on every check out of the printer as if it were the harbinger of the rush that steadfastly refused to come. It was difficult to see from the grill station at one end of the line to the fryers at the other because of the wavy heat-haze—the air squirming, like staring through aquarium water.

Five o’clock came and went. It seemed to me suddenly like there wasn’t enough air on the line for all of us to breathe. I had chills. Cold flashes skittered up and down my spine while my front half baked. This being Florida and me being too young for menopause, I imagined it was malaria and stood firm, waiting for the hallucinations to kick in. With the ventilation hood going full blast, Roberto and Chachi couldn’t keep the pilots on their unused burners going so had to keep kissing them back to life—leaning over and blowing across the palms of their hands to get the flame from one to jump to the next with the gas turned all the way up. The alternative method: smacking a pan down on the grate at an angle and hard enough to catch a spark. They did it over and over again until Floyd yelled at them to quit it. After that, they fought over the galley radio. After that, they amused themselves by drinking the cooking wine (sieved through a coffee filter to separate out all the grease and floating crap and then mixed with orange soda) and pegging frozen mushroom caps at Jimmy whenever his back was turned.

At some point, Jimmy—in an attempt to catch whoever was throwing things at him, and half in the bag to begin with—spun around too fast, caught his foot on the edge of one of the kitchen mats and went down hard, his head spanging off the rounded edge of the expo table with a sound like someone throwing a melon at a gong. He was unconscious before he hit the floor.

There was an instant of shocked silence, then a crashing wave of laughter. Seeing anyone fall down is funny, but seeing a drunken fat man fall down beats all. One of the waitresses ran for the hostess (who also doubled as FOH manager), and she came at the best sprint she could manage in her stiletto heels and stirrup pants. The prep/ runner crew treated Jimmy like any other heat casualty, breaking in a wing and descending like Stukas to drag him clear of the flow of service. It took four of them. Jimmy was a big man and moving him was like trying to roll a beached whale back into the sea.

They dumped him, loose-jointed, beside the cooler and calmly went back about their business. Jimmy’s T-shirt (Pantera on that day, I think, black and sleeveless, making his thick, pasty-white arms look like they were made of lard) rode up over his hairy, pony-keg belly. His eyes were closed. There was no blood, which secretly disappointed us all.

Floyd spoke to the line. “No one cops to this. No one snitches.”

He ordered Roberto to the wheel, shifted Dump, the roundsman, from second steamer (backing me) to second fryer (backing the new FNG), and vaulted the line to take Jimmy’s place at expo himself.

As was only to be expected, that was when the real dinner hit finally came tumbling in. With the hostess seeing to Jimmy (and probably quietly looking to see how she could get at his wallet) the floor was left unmanaged. Waitresses double- and triple-sat their own sections in the absence of an egalitarian hand. The ticket machine began to spit. Like a pro, Roberto false-called a half dozen steaks to the grill, crabs to the steamers, and twenty-upped fries to get things rolling in anticipation of steaks going well-done and missed sides down the line, then started working actual tickets, hanging them ten at a time. The machine didn’t stop. The paper strip grew long, drooping like a tongue, spooling out and down onto the floor. On the galley radio, the DJ came back from a commercial and kicked into the Misfits doing “Ballroom Blitz,” and I—up to my wrists in meat and blood, crouching down at the lowboy trying to retrieve cheap-ass skirts and vac-pac T-bones from the dim interior—yelled that I’d kill the next cocksucking motherfucker that touched the dial. After that, we were in it, the machinery in motion.

Sturgis and I sang along with the radio, bouncing on our toes, burning energy while we had it and twirling tongs on our fingers like gunslingers before dropping them onto the steamer’s bar handles. We shouted callbacks to Floyd with the strange, exaggerated politeness and house slang of the line: “Firing tables fifty-five, thirty, sixty-eight, thank you. Going on eight fillet. Four well, three middy, one rare. Working fourteen all day, hold six. Five strip up and down. Temps rare, rare, middy waiting on po fries, two well going baker, thank you. Wheel, new fires, please. We’ve got space.”

We yelled at Roberto, at Floyd, at the radio and each other. We yelled at the runners to bring more compound butter and plates of oil (a cheap trick for getting those grill marks to char faster—dragging the steaks through cheap salad oil, which scorched up black and nutty in seconds), and when we weren’t yelling, we were muttering, cursing, talking to the meat, the fire; begging and cajoling more heat out of the grills, bricking the steaks with iron weights, throwing them in the microwave to speed them along to temp, constantly poking and prodding and plating them to the rail; waiting for po—for starch—and veg and wrap.

Jimmy regained consciousness and sat glaze-eyed, staring and concussed on the floor until he was capable of standing without help. He retook expo like the marines taking a hill: lurching, wild-eyed and under fire. Floyd came back onto the line at the wheel. Roberto surrendered his position without a word, just turning and going straight back to his burners one step away with no interruption in the flow of orders. On fryers, the FNG was so deep in the weeds and lost that Dump had to crutch him full-time while I racked and emptied the stinking steamers, leaving dozens of pounds of crab legs and freezer-burned lobster tails and hundreds of clams to die in hotel pans under the heat lamps. The smell was . . . staggering.

Then the FNG passed out from the heat. The runners plunged onto the line, hip-checking their way through the chaos to drag him off.

Floyd shouted, “Hydrate that bitch!”

The FNG was dumped over a floor grate near the coolers and doused with ice water. He came to with a scream, sputtering and kicking, and while he recovered, another runner stood stage at his station, slicing bags of fries open with a silver butterfly knife he’d pulled out of his pocket and emptying them straight into the smoking fryers; fishing out an order at a time with long tongs and setting up sell plates under the lamps to catch up, his fist wrapped in a wet side towel to defend against the rivulets of hot oil that ran back down the grooves—another good trick, one that the FNG just hadn’t had time yet to learn.

The night rolled on. Ice buckets were called for and installed at each station. You bent down and stuck your whole head in whenever you started to see fireworks—sure sign of an impending blackout. A plastic bottle of cornstarch made the rounds, everyone on the line dumping the stuff right down the front of our chef pants to soak up the sweat and keep the tackle from sticking. “Making pancakes,” that was called, from the way the starch caked up on either side of one’s ballsack.

I went down around nine. I felt it coming—the blackness squeezing into my head like heavy velvet. There was time enough to step back so I didn’t topple over on the grill, then just the sensation of falling for miles.

Mark of one’s perceived toughness: I was hydrated on the spot, Sturgis upending an ice bucket onto me while Floyd frantically waved off the runners. The floor was ankle-deep in shit—food scraps and packaging and dropped utensils and dirty towels. All the detritus of a killer service in a restaurant where people didn’t care as much about what they were eating as they did about its being served fast, cheap and in gargantuan portions. I lay there on my back like I was trying to make a garbage angel, blinking, gasping and spitting. When I stood up again, I had a crab leg stuck in my hair.

Sturgis called me Crab Head from then on out.

I went right back to the grill—not because I was so tough or because I wanted to, but because I was too embarrassed to do anything else. I had to strip out of my chef coat and T-shirt because the water in them started to boil. The guys whistled at me. Sturgis rubbed my thin, bare belly. A runner brought me a dry jacket, and while I was shrugging into it, there was a sudden, odd quiet. The ticket machine had paused—first time since the rush had begun in earnest. We all stared as if it were our own hearts that’d stopped beating.

“Fire all!” Floyd yelled. “Hang ’em and bang ’em. Expo, all call.”

We ran the rail, cooking everything in sight in one massive push to get ahead of the curve. And when it was done, Sturgis and I cooked through the last half hour of service on autopilot, going on gut and reflex with sore hands and boiling blood and eyes like broken window-panes. Things were winding down, the siege broken, the fort once again saved from the Indians, whatever. We wiped down, wrapped and stored our station while the last of the straggling tables cleared, then gave the line over to the prep crew, who were also responsible for all the heavy cleaning. Four hours had snapped past like a minute.

This was The Life. The part they can’t teach in culinary school, don’t ever show on TV. The unscheduled death and disasters and heat and blistering adrenaline highs, the tunnel vision, the crashing din, smell of calluses burning, crushing pressure and pure, raw joy of it all as the entire rest of the world falls away and your whole universe becomes a small, hot steel box filled with knives and meat and fire; everything turning on the next call, the next fire order, the twenty, thirty, forty steaks in front of you and the hundreds on the way. This was what made everything else forgivable. And I knew that if I could just do this one thing, all night, every night, under the worst conditions and without fail, nothing else mattered.

Please, God, just this. The rest is only details.

We retired, with the rest of the crew, first to the dock to pass a bowl around and hammer down cigarettes, then to the locker room to change, then to the bathroom—transformed briefly into a white-trash version of Studio 54 with ugly men in terrible clothing dry-swallowing OxyContin tablets or tying off in the stalls with the proficiency of practiced habit—then, finally, to the bar, where the air tasted of tin and overworked air-conditioning machinery and the hostess stood pouring restorative cocktails of pineapple juice and well vodka into finger-smudged highball glasses.

It took a minimum of two drinks before any of us were able to get it together enough to speak, three before what came out of our mouths approached language. We talked about the night the way impressionists painted, in splashes of color and hard, angular jive; speaking in broken sentences, disjointed bursts of wasted rage mixed with thumping bravado bouncing back and forth while we sat, all clotted up around the service end of the bar in too few chairs as if, even in an empty dining room, we strove to isolate ourselves from where the customers—the enemy—sat and business was done.

Floyd sat slumped over with his arms folded on the bar top, head resting on his crossed wrists. Sturgis and Chachi were chattering at each other like monkeys, grooving on the same Colombian frequency. Roberto and I sat bracketing the FNG (who’d finished out the night standing, which was noble enough), filling him with liquor and trying to name him now that his cherry had been popped; running down a list of funny Spanish words, French, kitchen slang, settling finally on Chupo—garbled Spanish for “I suck.”

Jimmy came teetering out of the kitchen like a sea captain negotiating a rolling, rain-slick deck. The entire left side of his head had swollen like he’d caught half a case of encephalitis, but he said nothing about it—seeming to have forgotten the mushroom-cap mutiny entirely, like it was a hundred years ago and never that big a deal to begin with. He squeezed my shoulder in passing, patted Roberto’s belly, grabbed Chupo by the back of the neck and shook him like a puppy, telling him he’d done good, that he would be on the line again tomorrow night, and that he shouldn’t be drinking because he was only eighteen, but if anyone outside the house said boo to him, to just tell them he’d robbed a liquor store.

Jimmy made the rounds and ended up at the bar beside Floyd. I watched him lay a hand gently on his top guy’s back, between Floyd’s bony shoulders. They talked too quiet for me to hear, but Floyd would raise his head only to answer direct questions, staring off into some weird middle space between his eyes and the bar mirror when he did, then settling his head back again onto his arms. He looked like some wasted angel, a stick-skinny cherub, a galley saint—white as alabaster, beat to shit, spacey from the junk and exhausted. No one lasted more than a few hours or a few days on the line at Jimmy’s Crab Shack. If you made it a month, you were almost like family.

Floyd had been holding down his post for two years.

LATER THAT NIGHT, full of house liquor and smelling like low tide on the gutting flats, I went out back alone for a quiet smoke. Stumbling through the large, darkened kitchen, my fingers trailing, bumping along the tile walls, I went out onto the dock. There, away from the insulating comfort of cooks, away from the furious noise and action of the hot line, away from the familiarity of plastic ashtrays and ice-frosted glasses, the language of kitchens, the screwheaded weirdness and zapped-out combat-zone chic of being a working cook at the ragged end of a long, bad night, all of reality came crashing back in on me. Here was only the night, the dark, the green, fecund stink and distant highway roar, the wet pressure of just trying to breathe in this swamp and the fat black cockroaches that crawled along the cement. Here was the realization of exactly how fast I’d fallen, and from what middling height.

Suddenly, the thought of crawling back to my room and my alleged fiancée, of smoking cigarettes, lying slit-eyed on the couch, too exhausted to sleep and watching another Spanish-dubbed version of Red Dawn on Telemundo, was all just too much. Standing rigid, eyes aching, feet throbbing, blood humming in the hollows behind my ears to fill the sudden quiet, I stared up into the night and the stars.

And maybe this should’ve been one of those big moments. Maybe I should’ve asked myself the big questions: What’s next, Jay? or How in the fuck did you end up here? It’s possible that I even did. Tired as I was, beaten cross-eyed like I was and just trying to catch my breath among the roaches, cigarette dog-ends and hot trash stink, the scene was certainly set for all manner of hammy self-indulgence.

This is my story. If I wanted, I could tell it exactly that way. I could make myself appear deep, introspective or wise. If I wanted to seem a tough guy, I’d just have me suck it up, light a fresh smoke and stride off purposefully, bravely, into an ambiguous future.

But I’m none of those things. I’m not wise, I’m dumb. I’m not a tough guy, I’m a coward. And the big questions? They all had small and inconsequential answers that were the same every time I asked them. I’d ended up where I did because of poor life choices and an even worse sense of direction. What was next was another cigarette, another drink at the bar, another rehashing of the night’s action.

“Hey, remember when . . .”

“Or what about when Jimmy . . .”

What was next was a swift retreat back into the warm, close embrace of a gang of cooks doing what cooks do best when there’s no more work to be done, which is everything possible to stall off having to leave the orbit of their kitchens, the nocturnal world and closed society of this thing of ours. To be in that—to be buried and surrounded by it, regulated by it, protected by it—was a comfort. It meant never having to be bothered by the big moments, the big questions.

So whether I found clarity there on the dock that night is immaterial. Whether I looked deep into my soul, wept and gnashed my teeth over blown opportunities and potential pissed away, or simply stood for a minute or two or ten, lost in the quiet and hot, wet dark. What matters is what I did, and what I did was turn my back on the outside, square up my head and go back to the bar.

What’s next? Tomorrow night’s shift and tomorrow night’s disasters.

And how the fuck did I end up here?

Because I couldn’t remember ever wanting anything else.

When we were done talking, Angelo shook my hand, told me to come back tomorrow, and when I did, to come in through the back door.

To a kid, that’s pretty exciting right from the start. I’d never walked in through the back door of anywhere except my parents’ house; had never seen the inside, the back room, the inner workings, of anything.

Okay, so it wasn’t like getting asked backstage at the rock show or being given a guided tour of the space shuttle. Just an invitation into the kitchen of Ferrara’s Pizza on Cooper Road, a neighborhood joint fifteen minutes’ walk from home. It wasn’t even a job so much as a test. “You come,” Angelo had said. “You like me, I like you, then maybe, eh?” He’d shrugged. “Then maybe you come back. Maybe not.”

The next day, I came back. I remember the smell of ripe Dumpsters, acidic like hot tomatoes and yeasty like stale beer. I remember the intimate crunch of my shoes as I walked alone down into the alley/parking lot behind the place, cigarette butts strewn on the broken concrete and the sound of raised voices on the other side of the rickety screen door that let into the kitchen. I heard shouting that sounded happy and serious both at the same time—impossible for me to reconcile with the simple emotional architecture of my particular and quiet suburban upbringing, where shouting only ever meant something bad—and impossible to translate because it was in Italian. I, of course, spoke not a word of Italian and (perhaps unwisely) had taken my first job in a place where Eyetie was the primary language. At the time, this seemed only a minor inconvenience.

I remember reaching for the door and feeling the dry heat baking through the screen on the palm of my outstretched hand.

Wow, I thought. That’s uncomfortable. Maybe the air conditioner isn’t working.

My second thought was that perhaps my choice (guided by my mother) in wearing a cadaverous blue button-down shirt and dark slacks with pointy-toed dress shoes to my first day of work had been a mistake.

But she’d been so proud, so happy. She’d insisted that—at least on their first day at a new job—everyone ought to dress as though they were attending a formal ball where one’s clothing, carriage and grace would be studied with some rigor. Because one never truly knew what they were in for on their first day of anything, it was all a matter of first impressions. And Mom was a big believer in first impressions. I’ve seen pictures of myself when I was a small child, in the years before I had any control over how I dressed me, and have witnessed the full flowering of my mom’s obsession with firsts. Coming home from the hospital, I looked like a small ham dressed for trick-or-treating in a Winnie-the-Pooh bunting complete with ears and paws. First day of school? Corduroy Toughskins and what appears to be a midget’s dinner jacket. In my first-grade school picture I am wearing a plaid bow tie and cummerbund and a gap-toothed grin so wide and crazy I am frankly amazed I wasn’t immediately prescribed something. At my First Communion, I looked like I should be serving drinks.

There is a treasured family photo of the four of us—Mom, Dad, me and my little brother, Brendan—posing on the edge of some mountain in the Adirondacks. It’s the first mountain the four of us climbed together, according to my mother. Myself, I’d say it was probably just taken in the woodlot down at the end of the street where I grew up, except that the ground behind us in the picture seems to be slanting upward at some ridiculously steep angle, and none of us are actually standing. We are, in fact, clinging, crablike, with fingers and bootheels to a rock outcropping and quite plainly trying to keep from sliding off to our deaths.

In the picture, my mom and dad both look like teenagers. She’s wearing shorts and hiking boots and pigtails and a look of manic, totally insane joy—an expression she wears, in one form or another, in every photo ever taken of her. He has a beard and a mustache, a flannel shirt, and the air of a man expecting to be eaten by a bear at any moment. Brendan is four years old so it doesn’t matter what he’s dressed in, but I have been attired in what appears to be a pair of miniature lederhosen like a tiny pitchman for European throat lozenges.

Anyway, Mom was big on firsts and big on dressing up for them. So it being 1988 and this being my first day of work, that was what I’d done—dolling myself up in my blue shirt with the too-large collar and poly-blend slacks and pointy shoes, looking like a short, skinny thrift-store version of the lead singer from Foreigner and having balked only at the addition of my best red leather tie. It was a pizza joint, I figured. A tie would just be overdoing it.

I pulled open the door and stepped inside. A radio was playing something unrecognizable and full of accordions. The air above and around the three double-deck pizza ovens was warped by the furnace heat radiating from them, like looking at the world through water, and everywhere else was thick with flour. It hung like a dusty cloud. The floor was gritty with it, every flat surface covered with it. The kitchen was a microcosm of motes and streamers, the thin stratus formations disturbed only by the passage of bodies through it and the suck of ventilating fans; a universe of flour that whitened everything it touched. To take a breath was to inhale whole galaxies of finely ground wheat, and the taste was like chalk on the tongue riding an olfactory wave of tomatoes, oregano and char. In two minutes, I’d sweated through my pretty blue shirt. After three, I was ready to pass out.

Angelo saw me standing there and broke out laughing, the cigarette in the corner of his mouth bobbing, the dusty skin around his eyes wrinkling. Natalie, his wife, made a face like I was the funniest, saddest thing she’d ever seen. And I just stood there, weaving in place and sweating while the accordions honked and everyone in the kitchen erupted in laughter and language I didn’t understand.

Finally, Angelo took off his glasses and wiped at his eyes. He pointed to a corner of the kitchen with a coatrack and some clean aprons stacked on a shelf. “Jason. Go. Change,” he said.

So I did.

MY MOM HAS THIS STORY she likes to tell. Well, not a story exactly. It’s more like an act, a shtick she falls back on whenever someone asks her what I was like as a kid.

Jay used to be such a sweet boy. You remember that show Family Ties? Well, Alex P. Keaton was his hero. He dressed like him, acted like him. He was always more comfortable around adults, you know? Very polite. Very smart. When he was little, he used to dress up all the time. One day he’d put on an army helmet and a backpack and be a soldier. The next day he’d wear this adorable little Boy Scout uniform and carry this bird book around with him. And I’d always get a call from Mrs. So-and-So down the end of the street and she’d say, “Cindy, Jason’s running away again. And he’s dressed like a spaceman or something.”

But he always came home, didn’t he? He always came home and he was always so sweet. See? Look at this . . .

At which point she will unearth a box of pictures or, worse, a framed-portrait collection of me through the years, from like five or six years old on through maybe eighteen. It’s an annual, one portrait from every year, arranged in an oval around one central photo, larger than all the others: a studio portrait of yours truly at eighteen looking like King Dickweed in a turtleneck sweater and blue jeans, brown leather jacket thrown jauntily over one shoulder, shot against a backdrop of disco lights as though I’d been caught by the paparazzi on the dance floor of the Dork Club.3 It has come to be known over the years as the Wheel O’ Jay.

With the Wheel serving her like documentary evidence, she will run through the years with quick and practiced ease.

This one, he’s what? Nine years old? Maybe eight?

I’m eight. She knows that perfectly well. And even if she didn’t, you’d think the Cub Scout uniform and the manic, wild-eyed leer of total elementary school picture-day psychosis would be a dead giveaway.

Look at him here, she’ll continue, her voice hard and nasal like Marge Gunderson from Fargo after a toot of helium. Isn’t he cute? That little tie and sweater vest. That was the year we all went to Atlantic City. To the boardwalk. He was so excited. And this one. Doesn’t he look happy? He was twelve here. Our first cat had just died . . .

Her affection for the photos starts to wane considerably by the late eighties, by the time I’d made it to high school. But still, she’ll shrug, tap at the glass. She will claim that I was nothing short of a perfect little mama’s boy until I reached my eighteenth birthday. An absolute angel, sweet as a gumdrop. Never mind that by eighteen, I’d already spent my first night in lockup, had already held and left three different jobs, had moved out (and subsequently back in) twice. She doesn’t mention to guests making the rounds of the Wheel what it was like to stand up in the judge’s chambers and agree to discipline a wayward son who was up on charges of possession of controlled substances, criminal trespassing and contributing to the delinquency of a foreign exchange student. She doesn’t tell the story of how, in an effort to get me to quit smoking on my seventeenth birthday, she gave me a pack of Marlboro Reds with a picture of my grandpa tucked inside the cellophane. He’d recently died of lung cancer (among other things), so the picture showed him in his casket. And she’d painstakingly written Hi, grandpa! in blue ballpoint pen on each individual cigarette, then somehow managed to get them all back in the pack.

Granted, that’s a creepy thing for a mom to do, but catching me by the elbow on my way out the door on my way to my senior prom and pressing a twelve-pack of condoms into my hand—is that worse?

No. What’s worse is that she’d wrapped them in pretty green paper. What’s worse is that she’d known full well my date was already waiting in the car and would be sitting right next to me when I—thinking that she’d perhaps purchased me some sort of functional gift like a hip flask or a pistol—unwrapped her little present. What’s worse is that the condoms she’d bought were ribbed.

She holds to her version of the past—the one in which I didn’t go wrong until the day I left the nest, went away to college, fell in with a bad crowd. And while there is some truth to that rendering (I didn’t discover amphetamines until college, for example, or their over-achieving cousin, crystal methamphetamine, and while I might have been marginally screwed up before that magic moment, after it I was both screwed up and awake for days at a time), it really happened much sooner than that. If my opinion counts for anything in this (and I’m not entirely sure that it does), I would say that everything changed—that I changed—when Angelo told me to. Mom can say whatever she likes (and will, given the least excuse or opportunity), but I was there. I was the one in my skin and in that ridiculous blue dress shirt and in those pointy shoes, standing in the heat and floury clamor of the kitchen at Ferrara’s, so when Ange wiped his eyes, pointed to the corner with the coatrack and aprons, and said, “Jason. Go. Change,” I did. It was the first order I took from a chef, the first of a million to come.

I STRIPPED DOWN to a white T-shirt and tied on an apron. I tied it wrong and Natalie had to show me how to do it correctly—strings crossed in the back, tied in the front, the bib tucked inside. The shoes were still a problem, but since I wasn’t going to work barefoot, I suffered with them. At least I looked like half a cook—the top half of one, crudely laced onto the bottom half of a short used-car salesman or the kind of guy who, in my town, would try to sell you shrimp or stolen stereos out of the back of a van.

My first duty was scraping sheet pans—using a bench scraper to flake off the skins of dried dough that’d stuck there after the trays had been pulled from the proofing box and the balls of raw dough removed, turned and laid in for a second rise in the humid air of the kitchen. Ferrara’s Pizza went through an amazing number of sheet pans in a day, working a two-rise rotation that kept probably two hundred of them constantly moving from box to racks to dishwasher and back again. Fifty or more would be used to hold raw dough headed for the proofing box—the balls arranged in two rows of six, twelve to a tray, twenty-some trays to a box—and would stay in there overnight. In the morning, someone (not me) would strip the proofed dough, now all stiff and leathery, from the trays, turn it, move it to a new set of clean sheet pans, stack the dirty ones on the floor, and shove the pans of turned dough into open racks near the prep tables. The dirty pans would be scraped, cleaned and stacked, awaiting the next batch of raw dough, and as Angelo took ball after ball of proofed and risen dough from the pans in the open racks, these would begin to form a second stack of dirties.

That stack then became my responsibility—each pan needing to be scraped perfectly clean of dried-out dough because any trace of it left behind would collect in the dish machine’s filter, eventually causing it to back up and flood the kitchen.

So I scraped the pans as best I could, but these were old pans, a batterie de cuisine that’d been in constant use for probably twenty years. They were warped, dented, buckled. There were pans whose sides had rolled, whose corners had pouched after thousands of violent, hurried probings with the sharp corner of a bench scraper. And each pock and ding and rough spot held flakes and dollops of dough; dough that sometimes came off easy like an old, dry scab, that sometimes turned to dust, that’d sometimes turned wet and gooey and would cling like a booger to anything it touched.

Each pan I finished on that first day I stacked on the loading end of the dishwasher until I had a mighty tower. I’d worked hard. I’d worked as fast as I was able, considering this was all completely new to me and I had no idea what exactly I was doing or how it fit into the grander scheme of Ferrara’s nightly pizza production. I’d gotten the basic gist of the necessary interaction between scraper and tray pretty quickly; had developed something like a system about halfway through the stack, which involved a flashy double pass over the flat surfaces with the blade of the bench scraper and then a vigorous (if not particularly effective) assault on the edges, corners and rough spots with the handle of a spoon I’d pulled out of one of the drying racks. If nothing else, it made me look as though I was working hard and, after my inauspicious entry into the kitchen, looking like I knew what I was doing was very important to me.

It took me almost two hours to finish scraping fifty or maybe a hundred trays. When I was done, I figured they’d now become a dishwasher’s responsibility, though I saw no dishwasher standing around anywhere, just waiting to jump in.

All around me, pizzas were being ordered and constructed with frightening speed. Things were being chopped and diced. The radio was playing and people were yelling and the ovens were cranked to their top settings, the doors left open, heat pouring out of them like liquid. The dinner rush was on and it was exciting, overwhelming. I felt lost, so I edged my way around the kitchen and stepped close to Angelo—wanting to learn how to throw dough, to ladle sauce and work the pizza stick (the big, flat, scorched wooden paddle with which pizzas were loaded and unloaded from the ovens), but terrified at the same time that I’d be asked to do anything other than to stand quietly in a corner and try not to faint. Timidly, I asked him what I could do next.

“Wash,” he said without looking at me. “Run the machine.” Then he made some strange stacking and lever-pulling motions with his hands, which were what passed for operating instructions for the dishwasher—a large, loud and (I assumed) expensive piece of industrial equipment full of spinning arms and harsh chemicals and boiling hot steam, which I was now expected to operate with some degree of expertise.

Again, I did my best, and again my best amounted to very little. I was quite pleased that I was even able to get the machine started, since I didn’t even know how to work our dishwasher at home and most of my dealings with unfamiliar machinery (such as toasters, microwave ovens, my dad’s Betamax or the lawn mower) involved pushing buttons or flipping switches at random until something unexpected—like a fire—happened. If nothing happened, I would get frustrated and resort immediately to violence, as if the toaster were deliberately trying to ruin my sandwich or the record player purposefully refusing to act as a centrifuge for the G.I. Joe action figures I’d taped to the turntable. Later, when my mom would demand to know who’d kicked the door off the broiling compartment of the oven or heaved my dad’s good power drill up onto the patio roof, I’d pretend I had no idea what she was talking about. I’d tell her it was probably Bren, then calmly go back to smashing my old cassette player with a rock.

Anyway, I was considerably less pleased when, within minutes, I’d managed to flood the entire kitchen. Probably pounds of unscraped dough had swollen in contact with the hot water inside the machine and found their way to the drain screen. At the first sign of trouble (which announced itself in the form of a stinking geyser of drainwater shooting up from the machine’s well), I panicked, jerked open the loading door in the side of the machine, and got a face full of superheated steam.

Natalie came to my rescue, indelicately muscling me aside and killing the machine with a quick stab at the big red button marked STOP that I’d entirely failed to notice. No one else in the kitchen even slowed down. Ignoring the floodwaters lapping at their boots and what I’d guess was probably a high and girlish screeching coming from me, they simply soldiered on, deconstructing fresh peppers, slicing pepperoni and throwing crusts with a focused concentration I initially took to be an intentional snub.

It wasn’t. It was just that cooks—good cooks, in the middle of a solid hit—are monstrously single-minded creatures. When the rush is on, a cook cooks. He puts his head down and just burns. A flood ain’t nothing till it gets so bad that it starts wetting his prep.

“Is okay,” Natalie said to me, touching her fingertips to my chest, my arms, gently tapping and trying to calm me or something. “Is okay. Try again.”

So I did. I ran the dish machine for the rest of the night, overflowing it at least twice more and kicking at its legs when no one was looking, but slowly figuring out its intricacies and what it could and couldn’t do. It could wash an evenly spaced and carefully arranged load of sheet trays provided it was coddled along and not put under any sort of undue stress. It couldn’t be made to work faster or better no matter what names I called it or how many times I hit it.

I found and cleaned the drain screen, familiarized myself with the machine’s proper loading and unloading, played with all the buttons and switches, whose labels and settings had worn off ages ago. I was ready to walk out after the first disaster, but I was no quitter so figured I’d at least hang in until the end of the night, when I would no doubt be summarily fired.

EVENTUALLY IT WAS NINE O’CLOCK. My fancy, pointy shoes were ruined. I’d run out of obscenities to yell at the dish machine. I was hurting and exhausted and frustrated, soaked with sweat and dishwater from the top of my head to my kneecaps. I was embarrassed at how bad a job I’d done, sorry for repeatedly flooding this nice couple’s kitchen, and I smelled awful. As the night wound down toward closing time, Natalie had shown me where the mop and bucket were kept, and I’d spent the final hour of my first day as a working man hopelessly trying to repair some of the damage I’d done. The combination of water from the dish machine and the flour that covered everything had coated the floor in a sticky, gloppy plaster, and my pointlessly swirling the mop around on the cracked cement floor was doing little more than moving gooey wads of gray-brown crap from one place to another.

One by one the cooks filed out, without a word, until just me and Ange and Natalie were left. I’d managed to corral most of the gunk near a central drain cut in the floor and was picking it up with my hands and depositing it in a garbage can because I couldn’t figure out any other way of getting rid of it when Ange called me over to the back door. I went. I assumed this was it and told myself that I would be a man about it. Ange stepped outside onto the back stair. I followed. He held the door open for me. For a minute, he did nothing but look at me—squinting through the smoke from the Marlboro that was forever hanging from his lip. I remember how great the cool night air felt on every inch of me that was sore and steam-burned. I remember how much better everything smelled than me.

And I remember Angelo smiling, lacing his fingers behind his back, stretching his whip-thin frame until his spine cracked, and saying, “You’re still here.”

Now over the years, at the conclusion of many other bad nights, I’ve returned to that line in my head. I’ve never been sure if he meant that as a question (as in “What the hell are you still doing here?”), as an expression of his frank disbelief (as in “After what you did, I can’t believe you’re still here”) or as a sort of existentialist’s comment on the nature of really bad first days of work, like “Even after everything bad that’s happened tonight, you are still here.” Personally, I’ve always preferred the philosophical translation because it makes me seem somewhat heroic just for not giving up. And it makes Angelo seem like the sort of man who appreciated the quiet heroism of fifteen-year-olds too dumb to work a mop but also just too fucking stubborn to quit.

However he meant it, though, I looked back at him and repeated, “I’m still here.”

Now, I thought. Now he’ll fire me.

He nodded once, reached into the breast pocket of his T-shirt, took out a cigarette and forty bucks and handed both to me.

“That’s good,” he said. “Tomorrow, same time, okay?”

If I’d had a glass of water handy, I would’ve done a spit-take. “Really?”

He shrugged. “Tomorrow will be better.”

I put the cash in my pocket and the cigarette in my mouth. He lit it for me with a battered Zippo. And then the two of us stood there, not talking, just smoking and feeling the cool night air.

I was in love. If I had to make a list of all the best moments of my life, then that one—standing there in the dark by the back door smoking a cigarette with Angelo—would be high up on the inventory. Maybe not at the top, but close. I swore hard that I’d do better tomorrow, and better than that the day after. I promised myself that I wasn’t going to let this guy down, ever.

And I did, of course. A hundred times in probably my first month alone. But at the end of every night, I was still there.

On my first night, though, anything was still possible. All the small successes and failures of a highly checkered life were far, far away just then, so when I was finished with it, I flicked the butt of my cigarette out into the dark and stepped down onto the gravel of the alley. I started walking away.

“Hey,” Angelo called after me. “Where you go? Finish the floor first, huh?” He jerked his shoulder back in the direction of the kitchen, back toward the clots of wet dough around the drain and the wreck of the dish machine.

I laughed, shrugged, and slunk back in past him. He stayed on the steps, lit another cigarette off the stump of the first, and stared off into the dark while the radio played quietly and Natalie counted out the day’s receipts on the glass of the front counter. I picked up the mop again and heard Angelo from outside, yelling at me.

“Tomorrow, wear better shoes.”

At this point, I would love to be able to say something along the lines of “And it was after this first inauspicious day and these encouraging words from my lifelong friend and mentor Angelo Ferrara that I knew for certain I wanted nothing more in my life than to become a chef.”

I would then settle comfortably into a straight retelling of my smooth rise into the ranks of American über-chefs; how I struggled against some sort of externally presented adversity, overcame it with the help of Jesus and a good woman, then went on to get my own Food Network show, my own line of retail sauces and marinades and my own restaurant with two Michelin stars and a reputation for otherworldly excellence totally out of line with its location on a small Pacific island accessible only by hovercraft.

I’d love to be able to tell that story because that story would be familiar. There would be a clear beginning—a first day of work (very much like the one I have described), some words of encouragement from a trusted elder that would kindle my love affair with food. This would be followed by a juicy middle, the ubiquitous training montage; a breakdown, or a shark attack; and a scene in which I collapse, weeping, in the rain, then am found and comforted by a beautiful woman. After that, I am healed. My path becomes clear, and I follow it steadily toward ridiculous success. As with all tales like this, it would end with my best girl and me riding magical dinosaurs off into the sunset.

These kinds of stories are comfortable, recognizable, easy to follow. They’re the kind of stories people like to read.

This is not one of those stories.

I feel like it’s my responsibility as the teller of this story to say that if you’re looking for some four-star confessional, for the cooking secrets of master chefs or some effervescent, champagne-and-twinkle-lights twaddle about bright knives, foie gras and sweaty love among the white jackets, go find another book. Plenty of other books out there deal with the glam end of cooking in what has become a grossly celebrity-driven industry. Books about food obsessions that come from clean, clinical and intellectual places. About cuisine that isn’t born of pain and damage. About chefs who don’t have any scars.

I know a lot of kitchens out there operate not at all like the hot, cramped asylums and dens of terrible iniquity that I came up through. I understand there are chefs who are true gentle geniuses. But I never knew any of them. I didn’t work on their lines. And I can only tell my story and the stories of my guys—the ones I knew and worked beside, fought with, loved better than brothers (and the occasional sister), labored under, and eventually left behind like some kind of miserable, slinking Judas for a desk job, a byline and health insurance. My guys named their knives the way rock stars do their guitars, got butcher’s diagrams of broken-down pigs tattooed on their asses, and went to jail for assaulting police dogs. They slept and screwed on the flour sacks in the basements of a thousand different restaurants; lifted waitresses (and sometimes customers) right up on the stainless and knocked the cutting boards loose; prepped cool, fat-slick lobes of foie gras with the skill of surgeons in restaurants where they never could’ve afforded to eat. They weren’t pretty. They weren’t nice. They smelled bad almost all the time. They weren’t the guys you see on TV. They were the guys who make the guys on TV look good.

They were the guys who cook your dinner.

And after that first night at Ferrara’s, I was one of them. My real story and the imaginary story I would like to tell may not have many similarities, but they do have one vital detail in common: love. I was hooked. I couldn’t wait to get back into that kitchen. Like the guy who ends up staying forever with the girl who mercifully unburdens him of his virginity, I’d found true love on my very first try.

Just like my mom had said, you never know what can happen on your first day.

TRUTH: I was fifteen years old when I went to work for Ange and Natalie, but I didn’t do it because I had any love for food or for cooking. The same is probably true of the majority of my peers—regardless of how their PR-spun bios might read. I know one who took his first kitchen job at sixteen because he had a crush on a waitress two years older than him. Another started washing dishes at fifteen because his boss let him keep a radio at his station and play heavy metal all night. Another did it to get off the family farm (where he now returns two or three times a year to clear the place out of expensive mushrooms and sugar beets and to fish the streams clean of trout). Another because it was either the corner diner or eventually taking his place beside his father at the factory where the old man had been working for twenty years.

I took my first cooking job for the basest of all possible reasons: because I needed money. I threw my lot in with Ange and Natalie just because Ange and Natalie were the first people I’d found who were willing to accept my fudged work permit and hire a fifteen-year-old kid whose only real skills were jerking off and quoting verbatim from Star Wars, Star Trek, Star Blazers and certain books on sailing and wilderness survival.

I didn’t want to be a chef. I was fifteen years old. If I wanted to be anything, it was a pirate or, failing that, a rock star (that I couldn’t play guitar and was hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean notwithstanding).

Still, by the time I was done with my first week as a working man, I’d at least gotten a feel for the rhythms and idiosyncrasies of the job. I could actually go an hour or more without anything terrible happening. In that hot, cramped, hectic kitchen, I was serving a purpose. Without me, sheet trays wouldn’t get scraped. Dishes wouldn’t get done. I liked to imagine that without me at my post, things in the kitchen would slow down, that the smooth operation of a crew who could, on a good night, serve out a couple hundred handmade pizzas would suffer.

Granted, without me there would’ve also been fewer messes, fewer catastrophic floods, fewer mushroom clouds of yeasty steam belching out of that damn ancient dish machine when some molecule of unscraped dough caused it to puke its guts up all over the floor and cease working for a half hour. I was becoming a skilled operator. I was becoming important. And if not important, at least it was nice to be expected somewhere.

Professional kitchens on the high end of the industry are staffed by small, private and extraordinarily well-trained armies and organized (in the best cases) along military lines. There are gods and generals, lieutenants and foot soldiers, all with vital jobs to do. But on the low end, kitchens are run like machines with people there only to serve the process, to carry out the necessary steps of fabrication whereby a bunch of produce, meat and dry stock is put into one end and, in short order, is turned into a pizza (or a cheeseburger or a churro or a sandwich) at the other. There is very little thought involved. No deviation from the process is allowed. At Ferrara’s, dough was made the way it was because that was the way dough was made. Sauce was strained because the sauce needed straining. Beautifully circular logic, pat and simple.

And yet, those who work to service the machinery of production are not mindless automatons. Just the opposite. To be useful, you have to be a smart automaton. You have to be adaptable and always prepared to acquire new skills—sometimes in a very large hurry. Everything you learn today is based on something you learned yesterday, on the utilization of skills and reflexes hammered into you over weeks and years.

So I learned and I adapted. I became a better dough scraper so that the dish machine would upchuck with less frequency. With the dish machine upchucking less, I made less of a mess of the floors. With the floors less messy, I had more time for scraping trays.

See? A beautiful system.

Now, when the dish machine chugged to a stinking, sweaty halt, I could diagnose the problem with authority (gunk in the thingamajig), decide on an effective course of action (first, kick machine; second, yell at machine; third, clean thingamajig) and effect repairs with expediency.

Being better at my job also gave me more time to escape the clamor and stand on the back step smoking cigarettes with Ange and the other cooks. Being outside got me, at least temporarily, out of the heat of the kitchen, and that was a big motivator. It also got me away from the kitchen radio, which was forever tuned to a station that, near as I could tell, played only one song that was twelve hours long, sung by a gay Italian man who’d recently been punched in the mouth, and prominently featured an accordion being played by a spastic and tone-deaf monkey.

After my first week’s work at Ferrara’s, a surprising thing happened. There was a second one.

And I don’t mean that there was a Friday, followed by a couple beers with Midge and Jimmy from accounts payable, a nice weekend of relaxation spent lounging on the couch, then a slow drift down into another Monday-morning commute.

No, there was Friday and Friday’s work (differentiated from my first four days by its being as busy in one night as it had been in the last four all put together) and Friday’s smoke on the back steps with Ange, and then, just like every previous day, there was Ange saying, “Come back tomorrow.”

I remember thinking that perhaps the old man was addled. It was hot in that kitchen, after all. It’d been a very busy night. And Ange was, to my teenager’s eyes, about three hundred years old. I thought maybe he’d forgotten it was Friday.