5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

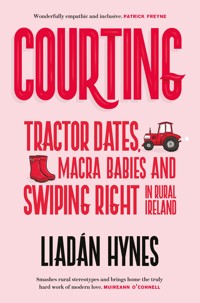

'Courting is a wonderfully empathic and inclusive book about love and community and all the different ways people can build a good life.'―Patrick Freyne Looking for love – the most human quest of them all – has been transformed in recent years, with new technology removing the need to be in 'the right place at the right time'. Dating has never been more convenient, varied or disposable and we Irish have taken to it with gusto ... and not just in cities. Courting: Tractor Dates, Macra Babies and Swiping Right in Rural Ireland tells a variety of honest and touching stories of trying to meet The One in a rural setting, where the ingredients for successful dating – choice, proximity, free time and, for some, alcohol and anonymity – aren't always guaranteed. Liadán Hynes travels from family farms to tiny islands, village pubs to remote communities, to sit down with childhood sweethearts, long-lost loves and singles, ever hopefuls and lonely hearts, as they navigate this quest through tractor dates, Macra, dating apps and more. They candidly describe swiping for love and moving for it, hooking up and settling down, all while inheriting a 24/7 farm job or coming out, returning to the home place or joining the pandemic exodus. Revealing the importance of community, diversity and, above all, hope and resilience, Courting is an insightful and unique window into dating in rural Ireland today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

COURTING

First published in 2022 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Liadán Hynes, 2022

The right of Liadán Hynes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84840-820-3

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-821-0

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland

For KevandMy sincerest gratitude to everyone who spoke to me for this book, for their time, honesty and energy.

Author’s Note

To protect the identity and privacy of some contributors to the book, the author has used pseudonyms where appropriate. In other instances, unique identifying characteristics have been altered in order to protect the privacy of contributors and their loved ones. Some quotes have been edited for clarity. All quotes included in the book are those of the relevant contributors.

Contents

Introduction

Part One: The Land

1 The Muddy Matchers

2 Tractor Dates

3 Macra Babies and Succession

4 A Bit of a Change

5 Tinder for Farmers and Someone to Talk To

6 The Home Place

Part Two: Blow-Ins

7 I Was the Last to Know

8 Love at First Sight

9 Pen Pals

10 Go on a Date and Drive for Five Hours

11 Cinegael Paradiso

Part Three: Finding Your Tribe

12 You’re Not Usually My Type

13 Small-Town Life Wasn’t for Me

14 I Didn’t Want to Be Alone

15 A Tinder Glitch

Part Four: Coming Home

16 How Are You Single?

17 I Never Want to Meet People in the Pub

18 I Knew of Him

19 Dating Apps Only Work if You Live in a City

20 Somebody from Home

21 A Smaller Pool of People

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Introduction

In 2018, Tinder released the Year in Swipe for the first time, a record of the most noticeable trends on the app that year. And there, just inside the top ten at number nine on the list of cities highest for Tinder activity, was Limerick. Two years later, in early 2020, dating.com listed Ireland as the third most active country in the world when it came to online dating.

My maternal grandparents met at a dance in Cork in the 1930s, when both were in their early twenties. After a long courtship of seven years, they got married and had seven children. My paternal grandparents, who hailed from Galway and Dublin respectively, met at an amateur dramatic society in the 1940s, also while both in their early twenties. They married and had four children. Both sets remained married for the rest of their lives.

My parents met at a house party in the 1970s when they were in their late twenties and early thirties, lived together for several years and eventually married. Unwed cohabiting wasn’t especially socially acceptable back then, something they felt particularly after my mother got a teaching job in a convent.

My boyfriend and I connected through Instagram direct messages (DMs), later realising we ‘knew of each other’ (a phrase that comes up often in interviews for this book, used to indicate a person one feels is safe, for being known, compared to the anonymity of internet dating). We’re both single parents, of one child each, in our forties.

How and who we date has changed utterly in Ireland over the past few generations: what age we are when we begin, or return, to trying to find a partner, and where we find them. Online dating has become the main method through which we expect to meet people. In terms of connectivity, the dating applications (apps) have made us accessible to people we would previously never have encountered, something especially relevant for people living in smaller communities. That’s the upside. The downside ranges from a culture of disposability in the face of endless choice, to communication that descends on occasion into harassment. Hardly anybody relishes the prospect of the apps, but most people accept their necessity if they want to find a partner.

Our appetite for settling down does not seem to be diminishing. According to 2016 census data, the married population in Ireland increased by 4.9 per cent between 2011 and 2016. That said, remaining married for life is no longer a given. Between 1996 and 2016 the number of people who were divorced grew, as did the number of those who remarried. The proportion of the population that is single increased from 41.1 per cent in 1996 to 43.1 per cent in 2006, then dropped again to 41.1 per cent in 2016.

Interestingly, the largest proportions of single people (aged fifteen or over) were in the cities: Galway was the highest at 53.5 per cent, followed by Dublin at 53.2 per cent and Cork at 51.9 per cent (Leitrim, Roscommon and Meath were the counties with the lowest proportion of single people). The younger the population of a county, the more likely it was to have a high percentage of single people while the older the population, the more married and widowed inhabitants there were. Towns with a population of 10,000 or more people aged fifteen or over had high numbers of singletons.

While married people as a percentage of the population increased between 2011 and 2016 – up from 47.3 per cent to 47.7 per cent – urban areas saw a larger increase than rural ones.

This book looks at the 21st-century dating landscape in rural Ireland: how we meet people, what dating looks like there, how online dating has had an impact on the countryside. Does the place you choose to live inhibit how you will meet someone? Do the traditional ways of meeting a partner – matchmakers, dances, the pub – still provide the most opportunities, or have they been replaced as we all disappear behind a phone screen? And if so, is this a good thing? Is it easier now, or harder, to find a match?

I wanted to look at the modern practicalities of dating in rural Ireland by speaking to as wide a variety of people as possible: people living in farms and on islands, in towns and villages, those who grew up in rural Ireland, some who never left, some who did and then returned, and those who moved there for the first time as an adult.

Dating services aimed specifically at rural communities have long existed. Among these are the annual Lisdoonvarna Matchmaking Festival, built out of our tradition of matchmaking (a process that was originally as much a business proposition as a matter of finding love); matchmaker Mairéad Loughman’s The Farmer Wants a Wife events; Macra na Feirme (not officially a matchmaking service, but a voluntary organisation which aims to foster community in rural Ireland, which acts as a place where many couples find love). And alongside them, the social outlets: social dancing, motor meets, investment clubs, sea-swimming. And now, to complement the online era: Muddy Matches, a website that allows you to ‘meet rural singles in Ireland’.

All these organisations in their own way acknowledge the specific conditions and challenges involved in trying to meet someone in rural communities.

Isolation – work that can be solitary, lifestyles that revolve around small communities – does not often throw a person in the way of meeting new people. As professional matchmaker Mairead Loughman put it, ‘if you put a radius in Tinder of two kilometres, and you’re in Dublin, regardless of what age group you’re in, you’re guaranteed you’ve got 2–3,000 people to pull out of. If you do that in some parts of rural Ireland, you possibly don’t have anybody. And if there are, they’re possibly your cousin, or they’re your neighbour-down-the-road’s daughter who you went to primary school with, and there were only ten kids in the class.’

It’s reductive at this stage to suggest that living in a rural setting inherently means living amidst conservative values. As some of the stories here will show, acceptance of diversity can be abundant. But in smaller communities, just by dint of numbers, anyone outside the ‘mainstream’ can find it harder to find others of a similar mindset. What if you’re not straight, not white – what is the experience of dating in smaller, rural communities like then? Conditions such as the experience of being single when it seems like everyone around you is settling down and beginning to have children; chatting on a dating app with someone you may run into professionally in the future; re-entering the dating world, maybe for the first time, after divorce; the value of someone who understands your historical frame of reference, who knows your place and the people from it; the dissonance between those who left and returned and those who always stayed; the tension of loving your home, but knowing it is unlikely to provide you with you a partner? Distance is a further factor, the matter of how you get to know someone when you live counties apart and are not part of each other’s day-to-day lives, and the later-in-a-relationship question of who’s going to move, given the high unlikelihood that you will meet someone living nearby. What do early dates look like if you’re driving long stretches to get to each other?

While the starting points were prosaic – how we meet, internet dating and social media and its impact on these things, social outlets, the technicalities of how it all works – so much more came out during my interviews for this book. Conversations about Tinder led to examinations of how being a single woman in a small town has changed, what kind of life one is ‘allowed’ in those circumstances, and about not wanting children in a society that feels as if it is centred around the family. Speaking to someone about growing up on an island led to a reimagining of the structure of a family. Talking to those in farming revealed matters of vocation, of generational guilt, of a love of a way of life that caused people to leave behind family, friends and place to move to Ireland.

These are stories about knowing what you want from life and finding the person who shares those priorities. In some cases, it turns out it is not a person, but a place that provides. A place which might, at the same time, make it harder to find your person. Or even a temporary person.

The stories in this book reveal that in the quest to find a partner, there can be a tension between love and place, that an attachment to place – to the very spot in the world that defines you and where you belong – can make you sacrifice the possibility of meeting someone in favour of the lifestyle you are afforded by the location you have chosen. Or that attachment may be the very thing that identifies exactly who you should be with: a person who understands that lifestyle, that place, and similarly prioritises it.

Part OneThe Land

1

The Muddy Matchers

It was 2009 in Borris, County Carlow, and the Muddy Matchers were there to host a speed-dating event, their first foray into the Irish rural dating scene. The Muddy Matchers are Lucy Rand and her sister Emma Royall, founders of the dating website muddymatches.co.uk. The next morning, the pair sat in a local café surrounded by people talking about the previous night – the same people unaware that its instigators sat amongst them. Lucy smiles at the memory. ‘It was the chat of the place. They didn’t realise that we were the Muddy Matchers. It was “shock, horror there’s been a speed-dating event”.’ The event, as it turned out, had been a huge success, it was ‘a hoot. We had a really good time doing it.’ Lucy smiles now.

Nearly twenty years ago, Lucy and Emma were early adopters in the field of what are referred to as niche dating sites, or more commonly apps which, rather than casting their net at the entirety of the singles market, identify specific communities, tastes and proclivities and cater exclusively to those. These days Muddy Matches is far from being the only one of its kind: name a preference or a community, chances are it has its own dating app. There’s Cougar, for mature women; Fitafy, a fitness dating app (‘meet active singles and friends who value health and fitness’); Frolo, for single parents; OutdoorLads; Trek Dating; Kippo, the dating app for gamers; Muzz, for Muslim and Arab singles, dating and marriage; Christian Dating Ireland (‘calling all single Christians!’); Veggly, vegan and vegetarian dating; Kink D: BDSM, fetish dating; Stache Passions, for moustache lovers; Redhead Dates (‘you’re sure to find your ginger flame’); Dead Meet, for those who work in the death industry; Bristlr, for beard lovers; Tastebuds, which pairs people in accordance with their musical preferences; and GlutenFreeSingles, for those who practise a gluten-free way of life.

At its most extreme are the invitation-only elite dating apps. Raya, Tinder for celebrities as it is often called, or The League – ‘are you told your standards are too high? Keep them that way … The League, a community designed for the overly ambitious.’ The possibility of being turned down upon application to a dating app, a potential further layer of rejection in online dating, has quite the air of what-fresh-hell-is-this to it.

Back when the sisters first launched their business, in the mid-noughties, it was the early days of internet dating, and looking for a partner online was only just on its way to becoming something that was widely considered acceptable, rather than an odd, somewhat embarrassing situation to find oneself in, in some ways an admission of failure. Match.com had launched in 1995, OkCupid in 2004, although it would be years before dating apps made the internet the first port of call for most daters.

LinkedIn had launched in 2003, followed by Facebook in 2004 and Twitter in 2006, all of which had meant that gradually, almost imperceptibly, people were becoming used to the impingement of the internet on their personal space, living parts of their lives online.

Lucy describes the perceptions at the time of online dating as largely something which felt shameful. ‘People were starting to talk about it in London. Unfortunately, it was kind of seen as freaks and weirdos, or people who were a bit desperate.’ Slowly, though, a shift was happening in people’s perceptions, she adds.

It was early 2006. The idea for a dating site that appealed specifically to people for whom country living was a priority, and who had a genuine understanding of what that involved, had first come about in the pub. Lucy was living in London when her sister Emma came to visit for the weekend from the countryside. Over drinks, she confided to Lucy about the difficulties of meeting people when living in a rural area. Had she tried online dating? Lucy wondered. She had, but it was full of ‘townies’.

Both sisters immediately realised the issue here. They had grown up on a farm in a village. They knew that this could both predispose a person to certain priorities about their way of life, and give them an understanding, insight and yen for rural life that those who grew up differently simply would not comprehend.

‘We just kind of figured that everyone knew that that was a thing, it was a niche,’ Lucy says. Surely there must be something specifically aimed at people living in the countryside, they thought.

They did some research and quickly realised that, while there were some sites aimed at people living in rural settings, they were very limited in scope. There was a niche within a niche: a specifically equestrian-related dating site, and also a matchmaking site that required a large fee in return for organising only a couple of dates.

Lucy and Emma knew there was a gap: space for something that was a bit of fun, aimed at people who shared a love of the countryside – not just those who were horsey; a space for those who were either already living in or wanted to get back to a rural setting, or who wished to move there for the first time and who were really aware of some of the specific challenges thrown up by farming or rural living; a space where these kinds of people could find each other.

Lucy points to the demanding nature of farming on a person’s time. ‘Farmers have to cancel dates because they’ve got trespassers or cows in a ditch. You can’t just stop that, it’s a way of life, it totally takes over. You’re always going to put the animals first, and the farm.’

Then there’s the isolation, which living in a rural setting can involve. She tells a story of a former client, a gamekeeper who lived in an especially secluded spot in Scotland. On rare nights out he would meet women and it would often go well – occasionally things might get so far as someone moving in. But within a month or so his partner would be struggling with the long hours he worked, with loneliness, the distance from everything.

‘He found it really, really hard to meet someone who could fit in with his lifestyle, and in the end he gave up gamekeeping for a woman because it had happened so many times to him. He never wanted to give up that work, but he wanted that other [domestic] side of his life as well,’ Lucy says.

Lucy and Emma didn’t imagine Muddy Matches would be a full-time career but decided to ‘have a bash at it’. They had been right when they had intuited that there was a desire for a dating forum which placed rural living at its centre. They wanted to create something where people who understood this way of life could find each other. It took off, and the site – yet to be an app (they’re a small, family-run business, these things take time, Lucy explains with a grin) – is soon to celebrate its fifteenth year in business. Their oldest Muddy Matches baby is now fourteen.

Not all their members currently live in a rural setting: ‘You don’t have to live in the countryside to be muddy.’ There are younger siblings who didn’t inherit the farm and were unable to afford a country property themselves. Now living in town, they are keen to get back to that way of life.

There are ‘signed-up townies’, those who aspire to a greener way of life and would like to find someone who wants to live off the grid with them. And then there’s a few people who like the idea of marrying a farmer, but don’t understand the farming way of life: ‘not really actually that muddy’, Lucy smiles wryly. Although the stigma around online dating was beginning to slowly shift when they launched the business, it was slower to dissipate in the countryside. This was even more pronounced in rural Ireland than in England, Lucy recalls. That said, soon after they launched their business in Britain, they began receiving emails from Ireland asking why they were not providing the service in this country. ‘Why don’t you have this in Ireland? We thought, why not?’

At that first event in County Carlow, daters were typically between their thirties and fifties. ‘Proper farming community, proper rural people came to that. It was a lot of fun.’ At the time of their event, they told the Irish Times that they had approximately 2,000 members from the island of Ireland and that, unlike their British members, amongst whom there were slightly more women, membership in Ireland was split equally between men and women. They had chosen Borris because it was one of the ‘top ten bachelor hotspots in Ireland’ – information gleaned from the 2006 census.

Now everyone dates online, so Muddy Matches has all ages. As the site is subscription-only, it typically attracts people more interested in a relationship than in hook-ups, something they can easily find on the free dating apps. People tend to pay for subscription dating apps for various reasons, for example to avoid the often-brutal nature of the free sites, unsolicited nude pictures, a sense of disposability. ‘It’s like a cattle mart … [the men] are showboating, and they think that they can take their pick of women,’ one woman I spoke to told me of how she felt about online dating. ‘They seem to have a few on the go at the one time. It’s very easy – I could be sitting here watching the TV and having a conversation with four guys if I wanted to, lining them up for each night of the week. That’s obviously what people are doing. I felt like I was on a shelf inside of a place, waiting for someone to pick me.’

There is the sense of being more likely to find someone on a site for which you’ve both paid to be a member. Privacy is also part of the appeal if your tastes run to something you’d rather keep off Facebook and out of the knowledge of those in real life (IRL).

Sometimes, spreading the net more tightly can actually have the inverse effect of revealing someone right under your nose who you might otherwise have missed. One of Lucy’s favourite success stories is a couple who had always lived in the same village, always noticed each other from afar, ‘maybe they’d seen each other down the pub but not talked.’ The village was big enough that they had moved in different circles. It was only through seeing their profiles on Muddy Matches that they realised they were both single and finally got together.

This kind of openness is not always the case; matchmaker and dating specialist Mairead Loughman describes sending a couple from the Tullamore area on a date. The date was taking place elsewhere, and when the woman going on the date asked if it could be moved to Tullamore so there would be less travel, the man, from a small town nearby, immediately refused. ‘He was like “definitely not, I’d be afraid somebody would see me”. People are more aware of perception, and the people around them and what people think as well.’

She also points to our reflex instinct in Ireland of finding a middle person, to connect a new acquaintance to those we already know. This is not always helpful from a dating perspective. ‘So, if you say you’re from Mullingar, then they say do you know that family, then you’re like, “oh my god, I know her uncle. Eject, eject.” There are so many times a guy will come back to me and say, “She’s a lovely girl, I don’t know if she’s the person for me, I would like to have met her again but I know her uncle, I meet him at the mart. I’d just be afraid, say if she took a shine to me, and it didn’t work out, sure I’d be the worst in the world. So actually, I’m not going to meet her for a second date.” That’s rural Ireland for you.’

2

Tractor Dates

Vicki had been out of a relationship for a while when she decided to try Muddy Matches. Now twenty-seven, she was then in her early twenties and, tired of being single, had decided to finally try online dating. ‘I started using Tinder, and, like, all those rubbishy, weird apps,’ Vicki, who is an upbeat, pragmatic kind of a person, says with a roll of her eyes. She tried Bumble and Plenty of Fish as well. ‘That was my first time using them and I just met weirdos.’

She found herself, ‘talking to people who never in a million years would you think about meeting in real life, because they were just weird. There were a couple of people who I went on dates with, and I just thought, No. No, not for me. Your pictures were lovely, but your personality is not what I’m looking for, thank you very much,’ she adds briskly.

Vicki grew up in Essex in England, ‘literally in the middle of town. What I would class as a normal upbringing, whereas I’m sure the guys here would class it as an abnormal upbringing,’ she laughs, waving a hand around at the farm where she now lives.

When she was five, she took up ballet lessons. At the time, her grandfather, who had always loved animals, a trait he has passed on to his granddaughter, suggested she also try horse riding. Her mother told her she wasn’t paying for both, so Vicki had to choose. She picked horse riding and ‘never looked back’.

Now she cannot remember a time when she didn’t think she would work with horses. She studied equine training and management at university, going on afterwards to work on the farm of a National Trust stately home. The internet dating was not going well when she came across Muddy Matches through an ad for the site on Facebook. ‘It piqued my interest, an online dating website, specifically for farmers-slash-outdoorsy people.’

The thought of paying a subscription fee initially put her off, however, and she decided to carry on with ‘crappy dates, meeting weirdos’ for a little longer. Nothing improved, and eventually Vicki thought, ‘Sod it. I’m going to pay for one month’s subscription, and I might meet somebody amazing.’

And she did. Within three days she had met her now boyfriend, Stephen.

‘My lifestyle didn’t really fit with a normal person’s lifestyle, someone who did a nine-to-five job in an office,’ Vicki explains. ‘I didn’t have enough in common with people I was meeting.’ When she would mention things like staying late at work to wait for the vet to attend to a sick animal, they would look at her blankly and say, ‘It’s five o’clock, go home.’

There’s a vocational element to how Vicki views her work – it and the rest of life are in communion with each other rather than being independent entities. It’s a sensibility that is common in farming, in that it is not just a job but a way of life. There is good and bad within this – a life spent so much in nature, but also an acceptance of the at times all-consuming demands of farming life; a love for the pace of it, relentless on occasion, but also less gruelling in many ways than more urban-based work.

For Vicki, the importance of an existence which prioritised the outdoors meant there was too much of a disconnect between her and the men she met on the regular apps she had been trying before joining Muddy Matches. It’s not that you have to be with someone who is exactly the same as you, she is quick to add. But some things are too big, too important, to not have a mutual interest in and understanding of.

‘Stephen and myself are incredibly different people, but the thing that we have in common is the love for farming and the outdoors and animals. And that is more important. I would much rather have someone … who is different than me, but who gets the lifestyle, than have someone who has all the exact same hobbies and interests as me but doesn’t like farming and animals.’

When they first connected on Muddy Matches, Stephen was living about forty minutes away, working on a large arable farm where he had been employed for three years on the tractors. Does she remember what it was that first struck her about him?

She grins. ‘He’s very pretty. I know it sounds like it should be so much deeper because the site is more specific, but you’re still meeting somebody based on their photograph, and there’s still that sort of shallowness of “yes, this person is pretty, let’s find out more about them”.’

Vicki messaged first: Stephen had also just signed up to the site. Numbers were soon exchanged and they began talking on WhatsApp. After about a week a date was arranged. He had organised bowling, which impressed her, ‘I think it’s the only thing he has booked in our entire time together, but it was enough,’ she laughs.

What happened next was what made this date so different from all the others. ‘At the end of the bowling I said to him, “We need to go somewhere else, let’s go to a pub or do something.” I didn’t want it to end. All the other dates, you get to the end of them and you’re like, oh thank god, I can go home again now – I don’t have to keep forcing the conversation.’

With Stephen she thought, no, I’m not done yet, you need to stay. Happily, he felt the same.

They went on five dates in the space of a week. It was like finding someone who understood exactly the thing that was most important to her, Vicki recalls. ‘We were having those conversations like, “oh my god I know what you mean”. Or he’d tell a story and I’d be like, “almost exactly the same thing happened to me, listen to my version of it”.’

None of Vicki’s family or friends is in farming, so she relished finding someone who had the same appreciation as she did. ‘And he is cracking. He’s always been awesome. I think I knew pretty quickly … yeah, you’ll do.’

The ‘talk’ – whereby two people agree that they will no longer speak to anyone else on dating apps – happens at various stages but for Vicki and Stephen it came quite quickly. ‘I think both of us had been still talking to a few other people on the website, because you go on so many rubbish dates that you kind of think it’s pointless not talking to anybody else. Quite quickly we had the conversation of “are you still talking to people on the website or not?”,’ she smiles shyly. ‘And you kind of go, “I’m not if you’re not.”’

It was February when they met and by the end of the summer they were living together. This acceleration in the progress of their relationship was mainly because of Stephen’s job, and the all-consuming pace of farming at certain seasons. Come the harvest, if she hadn’t ‘put the effort in’ she would never have seen him, so long were his hours. Some nights Stephen could be out working on the tractor until three, come home, get some sleep and then be back out again by eight in the morning. It’s not a timetable that leaves much room for conventional dating. Vicki was unperturbed by this.

‘There’s nowhere in that time where you can say “oh right, now we’re going for a date”. And I totally got that. That’s the life, that’s what you expect.’

To combat this, they came up with a concept that worked around, or rather with, Stephen’s work. Tractor dates. If Stephen couldn’t take time off work to meet Vicki, she would simply go to his place of work: the field, where she would sit up in the tractor with Stephen.

‘They have periods of time where the job has to get done by a certain date. But you can’t start the job until a certain time, so everything has to happen in the space of two weeks. If I didn’t go and sit up in the tractor for a couple of hours, I wasn’t going to see him.’

Your evenings no longer consist of sitting in front of the TV, you have to accept that, Vicki says. Instead, it’s ‘sitting in a tractor. Because otherwise you won’t get to spend time with the person’.

Dates on the farm get a mixed reaction. One woman I spoke to recounted in tones of can-you-believe-it how she was once invited to the milking parlour on a date. Another told me proudly of how her partner, also a farmer, had come to the farm she worked on for their date, a rare reversion in the gender balance of how these things tend to play out, she felt. Vicki loved tractor dates and looks a shade wistful when she talks about them and how she quite misses them. ‘There’d be times when you’d be like, “oh this is such a pain,” but on the whole I used to really love it.’

Vicki would bring her dog Wispa and food, maybe a pizza, and drive to a field where Stephen was working. Her favourite tractor dates were those on weekend mornings rather than weekday evenings, as it would be bright and she could spend the entire day with Stephen, driving up and down the field, chatting, listening to music.

Every so often Vicki would get out and take Wispa for a few laps around the edge of the field while Stephen kept the tractor going up and down. At lunchtime, she would head into town for supplies.

‘It would turn into a whole-day kind of thing, which I think we both kind of enjoyed, because he enjoyed the company and I enjoyed getting to spend time with him and being out and about. At the beginning of our relationship, I was much less farmy, so for me it was the novelty of it. It did very quickly become more commonplace and less exciting and new. Whereas at the start it was definitely “ooooh, look how big the tractor is, and I get to sit in it”,’ she laughs.