Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Phillimore & Co Ltd

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

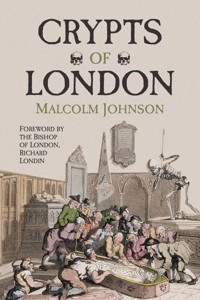

After the devastation of 1666, the Church of England in the City of London was given fifty-one new buildings in addition to the twenty-four that had survived the Great Fire. During the next hundred years others were built in the two cities of London and Westminster, most with a crypt as spacious as the church above. This book relates the amazing stories of these spaces, revealing an often surprising side to life – and death – inside the churches of historic London. The story of these crypts really began when, against the wishes of architects such as Wren and Vanbrugh, the clergy, churchwardens and vestries decided to earn some money by interring wealthy parishioners in their crypts. By 1800 there were seventy-nine church crypts in London, filled with the last remains of Londoners both illustrious and ordinary. Interments in inner London ended in the 1850s; since then, fifty-two crypts have been cleared, and five partially cleared – in each case resulting in the gruesome business of moving human remains. Today, many crypts have a new life as chapels, restaurants, medical centres and museums. With rare illustrations throughout, this fascinating study reveals the incredible history hidden beneath the churches of our capital. Malcolm Johnson is a retired priest, and has a PhD from King's College, London. His well-received St Martin-in- the-Fields was published by Phillimore in 2005.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 380

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Dr Julian Litten and Professor Arthur Burns.

With thanks and respect.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword by the Bishop of London

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

How long is it before a body and coffin will disintegrate?

Has anyone contracted a disease as the result of vault clearances?

What is today’s value of the sums given for fees and sales?

Where were the human remains removed to?

Is there a moral dilemma in exhuming bodies?

2 Worship and Service

St Marylebone, Marylebone Road

St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square

St Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside

3 Museums and Research

Christ Church, Spitalfields

St Bride, Fleet Street

All Hallows Berkyngechirche-by-the-Tower, Byward Street

4 Westminster Abbey

The royal vaults and tombs

The nineteenth-century excavations

Other burials in the Abbey

5 St Paul’s Cathedral

St Augustine-with-St Faith

St Gregory-by-Paul’s

6 City of London – Central

St Lawrence Jewry, Gresham Street

St Matthew, Friday Street

St Mary Aldermanbury

St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard Street

St Michael Bassishaw

St Mildred, Bread Street

St Stephen Walbrook

7 City of London – East

St Botolph-without-Aldgate

St James Duke’s Place

St Michael Aldgate

Holy Trinity Clare Street, Minories

St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate

St Dionis Backchurch, Lime Street/Fenchurch Street

St Dunstan-in-the-East, Great Tower Street

St Helen, Bishopsgate

St Olave, Hart Street

8 City of London – North

St Andrew Holborn

St Bartholomew-the-Great, Smithfield

St Botolph, Aldersgate

St Giles Cripplegate, Fore Street

St Luke, Old Street

St Clement, King’s Square

9 City of London – West and South

Christ Church, Newgate Street

St Dunstan-in-the-West, Fleet Street

St James Garlickhythe, Garlick Hill

St Magnus the Martyr, Lower Thames Street

St Martin within Ludgate, Ludgate Hill

St Mary-at-Hill, Lovat Lane

10 Other City of London Crypts (Cleared)

All Hallows-the-Great, Upper Thames Street

All Hallows, Lombard Street

All Hallows, Staining, Mark Lane

St Alban, Wood Street

St Alphege, London Wall

St Antholin, Watling Street

St Benet, Gracechurch Street

St George, Botolph Lane

St Katharine Coleman, Fenchurch Street

St Martin Orgar, Martin Lane

St Martin Outwich, Threadneedle Street

St Mary Somerset, Upper Thames Street/Lambeth Hill

St Mary Magdalene, Old Fish Street/Knightrider Street

St Michael, Crooked Lane, Fish Street Hill

St Michael Queenhythe, Upper Thames Street

St Michael, Wood Street

St Mildred, Poultry

St Olave, Old Jewry

St Peter-le-Poer, Old Broad Street

St Stephen, Coleman Street

St Swithin London Stone, Cannon Street

St Thomas Chapel, London Bridge

St Vedast-alias-Foster, Foster Lane

11 Other City of London Crypts (Uncleared)

All Hallows, London Wall, No. 83 London Wall

St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe

St Andrew Undershaft, Leadenhall Street

St Anne and St Agnes, Gresham Street

St Bartholomew-the-Less, West Smithfield

St Benet, Paul’s Wharf, Upper Thames Street

St Clement Eastcheap, Clement’s Lane

St Edmund the King, Lombard Street

St Ethelburga within Bishopsgate

St Katherine Cree, Leadenhall Street

St Margaret Lothbury

St Margaret Pattens, Rood Lane

St Mary Abchurch, Abchurch Yard

St Mary Aldermary, Queen Victoria Street

St Michael Cornhill

St Michael Paternoster Royal, College Hill

St Nicholas Cole Abbey, Queen Victoria Street

St Peter, Cornhill

St Sepulchre-without-Newgate

12 North Westminster

Christ Church, Cosway Street

Holy Trinity, Marylebone

St John, St John’s Wood

St George, Hanover Square Grosvenor Chapel and St Mark, North Audley Street

St-Giles-in-the-Fields, St Giles High Street

St Mark, North Audley Street

Mayfair Chapel, Curzon Street

St John the Evangelist, Hyde Park Crescent

St Mary, Paddington Green

13 Central Westminster

All Souls, Langham Place

Hanover Chapel, Regent Street

Holy Trinity, Kingsway

St Anne, Soho

St Barnabas, Pimlico, St Barnabas Street

St James, Piccadilly

St Paul, Covent Garden

St Paul, Knightsbridge, Wilton Place

St Stephen, Rochester Row

14 South Westminster

St Clement Danes, Strand

St John Smith Square

St Margaret, Westminster

St Mary-le-Strand

St Peter, Eaton Square

Maps and Tables

Notes

Bibliography

Copyright

FOREWORD

Christian faith emerged from the empty tomb and the early Christians, in great cities like Rome, often chose to hold their services in the catacombs. Most religions have offered an approach to the mystery of death, and part of what signals the evolution of human beings in the earliest times is evidence of care in the disposal of human remains.

Against this background, Malcolm Johnson has amassed some fascinating material on the ‘eternal bedchambers’; the crypts of the churches of the Cities of London and Westminster.

I vividly remember conducting a requiem at St Andrew’s Holborn on the occasion, described in this book, when the remains of centuries were reverently transferred from the crypt of the church to the City of London Cemetery. Despite visits over the past twenty years to many of the places described in this book, I learnt a very great deal that was new to me, and I imagine that Dr Johnson’s work will prove a goldmine to local historians and the organisers of ghost tours for many years to come.

Our ancestors practised contemplation of their own mortality as a fruitful spiritual discipline and while Crypts of London is a significant contribution to social history, it is also a reminder that ‘here we have no abiding city’. Instead we look for ‘The life of the world to come’.

Richard Londin,

Bishop of London

2013

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My grateful thanks to Richard, Bishop of London, for taking the time in the midst of his busy life to write the Foreword.

I owe a debt of gratitude to the late Miss Isobel Thornley’s Bequest to the University of London which helped me financially to publish this book based on my PhD for King’s College, London. The photographs enhance it greatly, and I thank my friends Paul Thurtle, Kevin Kelly and Ian Brown for climbing over gravestones in cemeteries to take them. David Hoffman, a professional photographer, whose work for my homeless centre at Aldgate attracted much attention (and money), spent a day in the vaults of St Clement, King Square (by kind permission of Fr David Allen), and I find it difficult to thank him enough for some superb illustrations.

Dr Tony Trowles, Head of the Abbey Collection and Librarian, and Mr Jo Wisdom have kindly checked chapters 4 and 5 for me. My editors, Cate Ludlow and Ruth Boyes, have been supportive and patient with me and Stephen Green checked my grammar so I am grateful.

This book is dedicated to Professor Arthur Burns (my PhD supervisor) and to Dr Julian Litten. Both have guided and helped my research.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Introduction

Coffin being placed on train (courtesy John M. Clarke).

City of London Cemetery (by permission of Gary Burks, Cemetery Superintendent; photographs by Ian Brown).

Brookwood Cemetery (by permission of Brookwood Park Ltd; photographs by Paul Thurtle).

St Marylebone (courtesy of the rector and PCC)

The Revd Christopher Hamel Cooke in the crypt. The Standard, 7 February 1983 (photo by Ken Towner, reproduced by Derick Garnier).

Memorial at Brookwood Cemetery (photo by Dr Garnier).

Inscription on the 1983 memorial at Brookwood Cemetery (photo by Dr Garnier).

St Martin-in-the-Fields (St Martin’s Archives courtesy of the vicar and PCC)

Plaque on south-west stairs to crypt.

Case of bones ready to go to Brookwood Cemetery, 1938.

The Revd Canon Pat McCormick, vicar, views one of the vaults, 1938.

A vault before clearance, 1938.

Crypt before clearance, 1938.

Crypt air-raid centre, 1940.

Eileen Joyce plays to the Darby and Joan Club in the crypt, c.1953.

The homeless centre in the crypt, c.1980.

St Mary-le-Bow (by courtesy of the rector and PCC)

‘The Place’ – Crypt café.

Vicar General’s court meeting in crypt, c.1970.

Sketch by Frederick Nash, 1818 (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives).

Christ Church Spitalfields

Skull and portrait of Peter Ogier (portrait reproduced by permission of the governors of the French Hospital, La Providence, Rochester, and skull reproduced by permission of the Council for British Archaeology).

Portrait of Louisa Courtauld (courtesy Julien Courtauld).

Skull of Louisa Courtauld (reproduced by permission of the CBA).

Skulls of the Ogier family (CBA).

Body as excavated (naturally mummified) showing textiles (CBA).

Part of the eastern parochial (CBA).

The northern parochial vault (CBA).

St Bride Fleet Street crypt (by permission of the rector and PCC; photographs by Stephanie Wolff)

A nineteenth-century iron coffin. Charnel house.

Heap of bones. Skulls.

All Hallows by the Tower (photographs courtesy of the vicar and PCC)

Entrance to the crypt. Undercroft altar and columbarium.

The crypt museum. St Francis Chapel.

Westminster Abbey

Henry VII’s vault: an engraving after a drawing by George Sharf (collection of Julian Litten).

Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827) Death and the Antiquaries, 1816, aquatint (reproduced by kind permission of Derrick Chivers FSA).

St Paul’s Cathedral (reproduced by permission of the Dean and Chapter)

The thirteenth-century Gothic crypt, etching by Hollar from Dugdale, 1658.

Effigy of Dr John Donne.

Wellington’s coffin suspended on chains above Nelson’s sarcophagus.

Today’s restaurant in St Paul’s Cathedral crypt (Graham Lacdao).

The remains of Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton being buried in St Paul’s Cathedral crypt, 1859 (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives).

Wellington’s funeral car (collection of Julian Litten).

St Botolph Aldgate

Three photographs of the crypt homeless centre (David Hoffman Photo Library).

St Helen Bishopsgate

Leaden shroud (collection of Julian Litten).

St Clement King Square crypt (by kind permission of the vicar, Fr David Allen; David Hoffman Photo Library)

Stacked coffins at eastern end.

The east-west passage.

The same passage.

The security cage of the Bedggood family vault.

Coffins in the Bedggood vault.

The entrance to the family vault of Mr Thomas Gall.

The north-south tunnel.

Coffins beginning to disintegrate.

St Andrew Holborn crypt (photos by Russell Bowes, courtesy of the Venerable Lyle Dennen and Dan Gallagher)

Anthropoid coffin. Steps from the church surrounded by coffins.

Jumbled coffins. Two skeletons share a coffin.

Lead coffin.

St Luke, Old Street (courtesy of Oxford Archaeology)

Coffin in crypt vault before clearance, 2001.

St James Garlickhythe (by permission of the rector and PCC; photos by Ellis Charles Pike)

The desiccated seventeenth-century corpse ‘Jimmy’, still resident in the church.

St Dunstan in the West crypt (by permission of the Revd William Gulliford; photos by Ian Brown)

Gate to north catacombs. Central vault.

Inside catacombs. Staircase to crypt.

Hoare family vault.

All Hallows Lombard Street (by courtesy of the vicar and PCC, All Hallows Twickenham; photos by Joe Pendock)

Father Time and the Grim Reaper.

Father Time.

St Clement Danes (photos by Alan Taylor)

West end of crypt, c.1956. Sunlight in crypt.

The crypt chapel today. Uncovered entrance.

Blocked crypt door.

St John Smith Square

Today’s crypt restaurant (Helen Bartosinski).

Holy Trinity Minories (by permission of the rector of St Botolph Aldgate; David Hoffman Photo Library)

Six depositum plates taken from the Dartmouth family coffins in the crypt. Notes by Dr Julian Litten.

ABBREVIATIONS

Repositories etc.

BL

British Library

GL

Guildhall Library

HS

Harleian Society

LDF

London Diocesan Fund Archives

LMA

London Metropolitan Archives

LPL

Lambeth Palace Library

ODNB

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

PP

Parliamentary Papers

TNA

The National Archives

UCL

University College London Library

WCA

Westminster City Archives

Source types

Br

Burial register

Ca

Churchwardens’ accounts

Tf

Table of burial fees

Vm

Vestry minutes

Unless otherwise stated the place of publication is London.

Key

[ * ]

Church still standing

[T]

Tower still stands

N.B.

Church or tower without symbol has been demolished

1

INTRODUCTION

The two cities of London and Westminster stank in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Thames, full of sewage, flowed past streets covered in human and animal filth. Smoke from chimneys made the air more putrid. The word ‘effluvium’, a noxious exhalation affecting the sense of smell, appears regularly in the early nineteenth century when a few Londoners began to suspect that there might be a link between disease, destitution and foul smells. One of these was the smell of death, almost unknown in Britain today, since corpses are embalmed soon after death. Such a smell inevitably led back to the Anglican burial places of the two cities, which were either crypts full of rotting coffins or graveyards, where bones were dug up after twenty or more years. Worshippers knew that beneath their feet as they walked into church or sat in their pews lay the decomposing bodies of their forebears, but, unlike in France, no one proposed changes until the 1830s.

In the early eighteenth century the City of London possessed seventy churches with crypts, thirty-one of which no longer survive. Westminster has had twenty-five churches with crypts since 1666, and only six have been demolished or leased after the human remains have been removed. Rarely do the published histories of these buildings mention these undercrofts. Two exceptions are Westminster Abbey, whose tombs are described in chapter 4, and St Paul’s Cathedral, whose crypt is described in chapter 5 (this relies heavily on a recent scholarly book).1 Obviously it is possible to visit the churches that have survived and establish precise details of their crypt; where it is not possible to enter, burial registers can give details of size and layout. For the churches that have not survived, the best descriptions of their undercrofts are often found in the faculties that authorised their destruction, and in vestry minutes recording the process of emptying the human remains and transferring them to a cemetery. Written accounts are rare, because few people visited these dark, dismal places apart from the sexton. However, an account by Frank Buckland of the undercroft at St Martin-in-the-Fields in 1859 has survived, and is contained in chapter 2.2 Two churches over the borders of the two cities – Christ Church Spitalfields and St Luke Old Street – are included because both have had the contents of their crypt removed, and thus provide valuable information. St Clement King Square is described because the incumbent has allowed me access.

Before proceeding it is necessary to clarify matters of terminology. Dr Julian Litten, a leading authority on funeral fashions and furnishings, describes a vault as ‘The eternal bedchamber’. His The English Way of Death is a good starting point for anyone interested in this topic, covering as it does burial customs over a long period.3 A burial vault, he says, is a subterranean chamber of stone or brick capable of housing a minimum of two coffins side by side and with an internal height of at least 5½ft. Anything narrower is best understood as a brick-lined grave. A crypt is a semi-subterranean copy of the floor plan of the building. The bays below a church’s side aisles were often private freehold vaults, partitioned, whereas under the nave was one large space for parish or public interments. Clerical corpses were usually placed under the chancel in open or closed vaults. Family brick graves or single brick graves covered with a ledger stone differed only slightly from vaults, and the incumbent decided where they should be – perhaps under a particular pew.4 Earth graves were often unmarked. The vaults could not be emptied or sold, so if a family moved away the space became unproductive; but in the City all this changed when the Great Fire destroyed many churches, and in the rebuilding programme vaults were cleared.5 The new crypts were open plan and space was easily available, although private vaults were soon located behind grilles in the bays around the walls. When a death occurred, families could ask the sexton to find where their forebears lay, so that they might be interred there too. Rarely did mourners enter a crypt, because the committal was said at its door or in church.

Until 1666 only the royal family and the aristocracy were interred in vaults, usually beneath a cathedral. Medieval monarchs were laid in tomb chests above ground, but Henry VII built a chapel at the east end of Westminster Abbey with chambers underneath, in which the Tudor and Stuart sovereigns still lie.6

After the Reformation, burial within a church was seen as a mark of social distinction. The nobility regarded it as their right, but by the mid-seventeenth century the professional classes were also seeing it as a sign of a successful career. Over the next century doctors, solicitors, high-ranking soldiers and ‘gentlefolk’ frequently left instructions in their wills for intramural burial, although some cautioned prudence and economy in arranging it because fees could be high. By law, according to the Revd William Watson, an eighteenth-century canonist,7 the incumbent alone decided who should be interred in the crypt:

Because the Soil and Freehold of the Church is in the Parson alone, and that the Church is not, as the Churchyard is, a common Burial-place for all the Parishioners, the Church-wardens, or Ordinary himself, cannot grant Licence of Burying to any Person within the Church but only the Rector, or Incumbent thereof … yet the Church-wardens by Custom may have a Fee for every Burial within the Church, by reason the parish is at the Charge of repairing the Floor.8

Precise figures of intramural interments are hard to establish, because rarely are they recorded separately by the parish clerk. In the eighteenth century the percentage of burials in church varied from 3 per cent in the poor parish of St Botolph Bishopsgate to around 60 per cent in the wealthy parishes of St Margaret Pattens and St Stephen Walbrook. An examination of parochial records in the two cities suggest that an average for intramural interments was between 5 and 8 per cent.

Burial fees represented a high proportion of parish income. According to my research, until 1700 the City of London parishes could receive between 7 and 20 per cent of their non-poor rate annual income from burial dues. In the eighteenth century most received around 7 per cent of their income from interments, although at St James Garlickhythe the average was 26.9. By contrast, all the five Westminster parishes had a high burial income at the end of the eighteenth century: it was around 35 per cent of the wardens’ income at St Martin-in-the-Fields and 25 per cent at St James Piccadilly. It thus made a significant contribution to the parish economy.

The cataclysmic Great Fire of 1666 had a profound impact on burial provision in the City of London: eighty-six churches were destroyed along with St Paul’s Cathedral (where the congregation of St Faith, who met in the crypt’s Jesus chapel, also lost their place of worship). Of these churches thirty-two were not rebuilt, although twenty-four in the east or north-east of the City were not affected. Crypts were destroyed with their buildings, so the space available for intramural burial declined.

During the next thirty years Wren, together with Robert Hooke, Peter Mills and Edward Jerman, designed and built St Paul’s Cathedral and fifty-one replacement churches. Most of Wren’s churches had vaults beneath them, and nearly all had burial grounds, which were well used because the population of the Square Mile was still large. Most of the sites of churches that were not rebuilt were now used as burial grounds.

During the next 150 years fourteen of these churches were rebuilt, either to enlarge them or because of dilapidation; all except St James, Duke’s Place, had a crypt as spacious as the church above.9 In Westminster the five churches in existence in 1600 all had undercrofts, and three of these retained them when rebuilt. Crypts were also given to the twenty additional churches built in Westminster before 1852. The clergy, churchwardens and vestries10 decided to use these spaces to earn money by interring wealthy parishioners in them, instead of using the space for other purposes. In doing so, however, they went against the advice and opinions of both architects and others. Some had always doubted the wisdom of burying the dead among the living. In 1552 Bishop Hugh Latimer thought it ‘an unwholesome thing to bury within the city’, considering that ‘it is the occasion of great sickness and disease’.11 Mainly for architectural reasons Wren was also opposed to burial in or close to the church, and his first designs for the rebuilding of the City contained no churchyards. Some years later he wrote to the commissioners responsible for building fifty new churches:

I would wish that all burials in churches might be disallowed, which is not only unwholesome, but the pavements can never be kept even, nor pews upright: If the Churchyard be close upon the Church, this also is inconvenient, because the Ground being continually raised by the Graves, occasions in Time, a Descent by Steps into the Church, which renders it damp … It will be enquired, where then shall be Burials? I answer, in Cemeteries seated in the Outskirts of the Town … they will bound the excessive growth of the City with a graceful Border, which is now encircled with Scavengers Dung-stalls. The Cemeteries should be half a Mile, or more, distant from the Church, the Charge need be little or no more than usual; the Service may be first performed in the Church.12

Sir John Vanbrugh agreed with Wren, and suggested that suburban walled cemeteries should be opened.13 When submitting his designs for fifty new churches in 1710, he described burial in churches as ‘A Custome in which there is something so very barbarous in itself besides the many ill consequences that attend it; that one cannot enough wonder how it ever has prevail’d amongst the civiliz’d part of mankind …’

Although in 1711 the second New Churches in London and Westminster Act had stated that ‘No Burial shall, at any Time hereafter, be in or under any of the Churches by this Act intended to be erected’, this applied only to the fifty new churches that were to be built, so other churches continued to use their crypts to earn money. Moreover, only three vestries obeyed the commissioners (those of St George Hanover Square, St George Bloomsbury and St John Smith Square).14 It soon became obvious that the ban on intramural burial was unenforceable, because the dues derived from interments were an important source of income for incumbents and their vestries.

Crypts could, however, have been put to other uses. After 1666 they might have been used for charity schools or perhaps rented to local merchants for storage. This would have been nothing new, because the crypt of the pre-fire St Mary-le-Bow had been leased for cellar storage, as had part of the crypt of All Hallows the Less. In 1612 the authorities of All Hallows, Honey Lane had re-possessed their vaults from a neighbour, and beneath St Mary Colechurch were shops and part of the Mitre Tavern. In these cases coffins had to be placed between the floor of the church and the roof of the vaults.15

During the eighteenth century the vaults of St John Smith Square, Westminster, were let to various tenants, but despite the temptation of increasing their income, the churchwardens refused their incumbent’s request to allow interments there. Early in the nineteenth century the vestry of St George Hanover Square also leased their vaults, which had never been used for interments, to a local wine merchant to lay down wine, but this was terminated after a while because the bishop objected.

Until the 1830s most people in England were buried in their local church or churchyard – ‘God’s acre’. Each knew their place in death as in life, with the wealthy coffined in the vaults below the building and everyone else buried in the churchyard – the poor, the unbaptised and social outcasts usually in the northern part, and the better-off in the sunny southern portion. Small city graveyards might not be able to make such distinctions, but their crypts were reserved for those who could pay substantial fees. Outside ‘The mingled relics of the parish poor’16 were jumbled namelessly together, possibly in pits, and pauper burial was feared by all. No member of the Established Church was refused burial; it was their right to be interred in their parish church or churchyard, although the unbaptised or those who had taken their own life had no such right. There is no record of a City church turning away plague victims in 1665, although pits rather than individual graves were used, the largest of which was in Aldgate, where 1,114 corpses were interred.17

In the early nineteenth century growing concern about the capital’s poor sanitary conditions and the need to improve burial provision coincided with the opening of new cemeteries beyond the City boundaries. Ten of the first thirteen successful cemetery companies in England were opened by nonconformists, who objected to the established Church’s privileges in burial provision. A few privately owned burial grounds already existed in the metropolis, mainly used by dissenters, such as Bunhill Fields, a short distance north of the City.

The first joint-stock cemetery in London was established at Kensal Green.18 George Carden, a London barrister and philanthropist, had visited Paris in 1821 and been impressed by the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise, which had opened in 1804.19 On his return he invited influential friends to consider whether the Parisian model might be copied. By 1830 he had assembled a provisional committee chaired by Andrew Spottiswoode, MP for Colchester, which resolved that ‘The present condition of the places of interment within the Metropolis’ was ‘offensive to public decency and injurious to public health’ and ‘afforded no security against the frequent removal of the dead’. This was an important consideration, because the trade in cadavers was lucrative: the demands for dissection were increasing. The General Cemetery Company was established, and in May 1830 a petition for a new cemetery was presented to the House of Commons by Spottiswoode, who mumbled so badly that at first members thought that a new road was being proposed.20 Land was purchased at Kensal Green in December 1831, and after negotiations with Blomfield, Bishop of London, about clergy fees, he consecrated it on 24 January 1833. Over the next twelve years a further seven joint-stock cemeteries opened, forming ‘a jet necklace around the throat of London’.21 They offered families a freehold tenancy for their deceased members that churches could not – unless interment was in a crypt.

The vestries responded in different ways to these challenges. Jealous of their rights but loath to authorise any expenditure, they needed to be encouraged by legislation to make changes. Fortunately another key player was now the local secular state: the minutes of the City Corporation, for example, show that on 23 September 1847 the City of London Court of Common Council ‘carried by acclamation’ a motion asking Parliament ‘to prohibit interment of the dead in the churches and churchyards of the City and other large towns’. Notably absent from the discussion until then was the government, whose members considered that this was the concern of local vestries. Now they were forced to take action.

The government was influenced by two important reports – a Report from the Select Committee on Improvement of The Health of Towns together with the Minutes of Evidence. Effect of Interment of Bodies in Towns (1842), and Edwin Chadwick’s Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns (1843). Chadwick was one of the men who most influenced Parliament and public opinion concerning sanitation and the undesirability of burials in urban areas.22 Formerly Jeremy Bentham’s literary secretary and playing a decisive role in Poor Law, policing and factory legislation, by the late 1830s he developed from his experience what he called ‘The sanitary idea’.23 At Bentham’s house in Queen Square, Chadwick met doctors, political economists and lawyers, who informed and helped his work on public health. Not only do the two reports illuminate the contemporary culture of interments in London, but the minuted evidence given by clergy, undertakers and others is detailed and important, making it evident that legislation was necessary.

Vestry minutes show the frustrations felt by congregations at the delays in setting up alternative burial arrangements, but only two vestries decided to open their own cemeteries. In 1854 St George Hanover Square Burial Board purchased 12 acres in Hanwell, and in the same year the St Marylebone Board founded the St Marylebone Cemetery, with 47 acres in East End Road. Why did others refuse to make what would almost certainly be a good investment? The response of St Anne Soho’s vestry was typical: ‘it would be a very great expense to buy a piece of land and build two chapels as required by law and maintain it’.24 Instead several vestries decided to buy land at Brookwood.

An ‘Act to make Better Provision for the Interment of the Dead in and near the Metropolis’ was passed by Parliament without a division on 20 June 1850, but had to be abandoned two years later since there were financial problems;25 it was difficult to implement; no mortuaries had been built; no cemeteries purchased; and no Officers of Health appointed. It was replaced by the 1852 Metropolitan Burial Act, which contained many of the earlier Act’s provisions. Parochial Burial Boards were to be set up, and the Commissioners of Sewers became the Board for the City of London and its Liberties. This was a severe blow to the incumbents and vestries of the Square Mile. Not only would their parishes lose considerable income, but also, unlike their Westminster counterparts, the incumbents, despite being compensated, would not be members of a Burial Board. Their influence over burial provision had ended, and although the archdeacon of London, William Hale, complained, it was obvious that the City Corporation had no intention of involving the clergy in the work of the Commissioners of Sewers. Hale disagreed with his friend Blomfield on intramural burial, but did not say so until his lectures and Charge to the clergy of 1855.26 It occasioned a rare joke from the bishop: ‘I have two archdeacons with different tastes: Sinclair is addicted to composition and Hale to decomposition.’

The 1852 Act allowed the Parochial Boards to raise money from the Poor Rate to buy land for new cemeteries, and confirmed that the sovereign could, by an order-in-Council, close urban crypts and churchyards; this began to happen over the next few years. An exception was made for Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s, some private freehold vaults and for Quaker and Jewish burial grounds if they were not injurious to health. The Queen could also make specific exceptions – the only example traced being that of St Stephen, Rochester Row for Baroness Burdett-Coutts and her friends Dr William Brown27 and his wife Hannah, the baroness’s adored governess and later companion. The baroness had prepared her own tomb there in 1850, but when she died on 30 December 1906 she was buried in the Abbey, after a dispute with the Chapter who would only accept her cremated remains.28 They eventually changed their minds, and so her body was buried close to the memorial of her friend Shaftesbury on 5 January 1907.

Over the next few years all the vaults and churchyards in the two cities were closed. In consequence the clergy lost influence, and contact with their parishioners began to wane as families opted to use the new cemeteries, realising that they would no longer be able to ‘lay their bones beside those of their relatives’.

Sextons and clerks, unlike incumbents, received no compensation for their lost burial fees. Furthermore the parishes themselves lost considerable income. My research suggests that in the City of London the ten parishes with a population over 3,000 lost an annual income of between £30 (today £3,420) and £70 (£7,980). The monetary loss in the twelve Westminster parishes was much greater, because all except St Mary-le-Strand had large populations with a large number of interments. The annual parish burial income, which now ended, would have varied from around £6,000 (£684,000) at St Margaret Westminster, £2,500 (£285,000) at St Marylebone and £378 (£43,092) at St James, Piccadilly.

What happened to the crypts and churchyards now that they were closed? Over the next 150 years many churches were demolished for road widening, to construct new buildings such as the Royal Exchange, or to raise funds. Sales were obviously a lucrative source of revenue, and parishes, diocese and Church Commissioners (after 1836) shared the proceeds. In the City of London since 1666 there have been ninety-seven separate sales and one long lease of churches and/or churchyards. Obviously much depended on the size of the site, but where a church and churchyard were sold the sum received varied from £2 million to £13.5 million in 2012 values. In Westminster, where there have been thirteen sales of burial grounds and nine sales of churches with crypts, the sum paid for a church and churchyard varied from £3 million to £12½ million in today’s terms.

In Westminster there have only been eighteen sales of Anglican burial grounds and four of churches with crypts, with one still to be sold, but the sum paid for only nine is known.29 It is unlikely that more will be found because, although the London Diocesan Fund Archives revealed some sums, the Church Commissioners informed me that the files relating to post-war sales of burial grounds were ‘destroyed as part of a departmental appraisal of records a number of years ago’.30 It is also unlikely that there will be further sales because the local authority would almost certainly not give permission.

Today fifty-nine of the churches in the two cities have a crypt the same size as the church floor, of which ten are fully cleared and in use, five are cleared but empty, and five are in part use. Three crypts that have never been used for interments are also in use. It could be argued that this is a surprisingly small percentage of cleared space, not least because in central London meeting rooms are much sought after. Before 1852 these undercrofts contributed significant income to the parishes. Until a survey is conducted of the thirty-three uncleared crypts it is impossible to decide if they could be cleared and used.

The removal of human remains has always been a complicated business, involving the parish, diocese, Church Commissioners, the local authority (after 1881), Home Office, undertakers, architects and builders. The costs were and are considerable, but if the reason for clearance was sanitation, or what today would be called ‘health and safety’, a charge could be made on the rates. If a building including the undercroft was demolished in order for the site to be sold, then the cost was taken from accrued profits. If the building remained and a new use for the crypt was found, then an appeal for funds was made, such as at St Bride Fleet Street in the 1950s, when its museum was equipped from the gifts of nearby publishing firms. Other churches have attracted grants from the Lottery fund, statutory bodies, charitable foundations, business houses or individual donors.

After 1852 there were three possible functions for a cleared crypt – to be of service to the community, which might include the congregation of the church, to earn money for the church, or a combination of both. The space might be used for worship, social service, parish space, restaurants or museums, and these are described in the chapters that follow. The first time a crypt cleared of human remains was used for a purpose other than storage was in 1915, when the vicar of St Martin-in-the-Fields, Dick Sheppard, set up a canteen to welcome men returning from the Front (see chapter 2). Crypts were also used during the Second World War as air-raid shelters. Geoffrey Fisher, Bishop of London, was scandalised that an incumbent was considering applying for £100 (£4,740) compensation, so on 16 February 1940 he told Prebendary Eley of the London Diocesan Fund, who had described them as ‘lumber-holes’, that ‘a vicar or parish should not try to profiteer over its use as an air raid shelter’.31 Eventually the rent was fixed at £1 pa Another possible use is the interment of ashes, but at present only eight churches have a columbarium.

Three parishes have demonstrated that their crypt can produce a good income to fund their work and worship; forty-four crypts in the two cities produce no revenue for their church; and six only a small income. However, before starting a project the incumbent and the Parochial Church Council should have a clear aim and vision of what the use will be, obtain the approval of the diocesan authorities, draw up a business plan and consider how the necessary funds can be raised.

Finally, this book poses several questions:

HOW LONG IS IT BEFORE A BODY AND COFFIN DISINTEGRATE?

Interment in a crypt obviously preserves a corpse and coffin longer than if it was buried in a churchyard. Even so, at the exhumation of 983 bodies, dating from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, from the crypt of Christ Church Spitalfields in the 1980s the state of preservation of those in coffins varied from virtually complete, including skin, hair and internal organs, to a sediment of crystal debris, being all that remained of the bones. If lead had been used, as it was in this crypt after 1813, this preserved the cadaver longer, but if air or water was allowed to penetrate then decomposition became quicker.

There are, however, stories of completely sealed coffins exploding, which is why sextons often pierced the lead. The 1842 Select Committee examined an undertaker, George Whittaker, who told them that gas can escape from a lead coffin: ‘Some drill a hole, put a pipe in, and then […] set the gas alight. It burns for 20 minutes.’ The 1843 Supplementary Report contained evidence from Mr Barrett, a surgeon and Medical Officer of the Stepney Union, who observed that he knew of a coffin which had exploded in a vault with ‘so loud a report that hundreds had flocked to the place’, and a great number were attacked with sudden sickness and fainting.

The speed of decay of vault-deposited cadavers depended on a number of factors: age and weight at death, what the individual died of, how soon after death the body was encased, and the weather conditions at the time of death. Crypt coffins were often covered with charcoal, which absorbs the smells, and quicklime, which acts as a disinfectant, although insects might bore into and weaken wooden coffins. After a while the coffins were occasionally removed elsewhere, as at St Martin Ludgate, but most remained in situ, although the sexton might re-stack them if more space was needed. At Spitalfields coffins were often stacked up to seven high, which meant that the lowest could have a quarter of a ton pressing on it, so even lead caskets might be flattened, particularly if the atmosphere was damp.

Water from the body is sufficient for the formation of adipocere (a chalky wax-like substance generated from fat deposits). If the lead coffin was standing at an angle then the part of the corpse soaked in body liquor often showed signs of preservation, while the part of the corpse above the liquor was skeletonised. Coffins containing sawdust packing yielded clean, dry bones.32

Decomposition is much quicker in soil. A body decomposes faster than its coffin. After two years in soil the coffin remains (unless the soil is very damp), but inside the coffin only bones, hair and skin tissues are left. Wet soil means everything rots quickly, although a chipboard coffin could be intact after sixteen years because it contains resin.33 The survival of bones depends on the acidity of the soil; chalk preserves them, but acid gravel dissolves them quickly.34 Bones will disappear eventually, but how long will that take? Remains in graves from Neolithic cultures (at least 6,000 years ago) are still being found.

HAS ANYONE CONTRACTED A DISEASE AS THE RESULT OF VAULT CLEARANCES?

Dr Julian Litten knows of one. In October 1902 part of T.G. Jackson’s scheme for re-ordering the church of St Thomas, Portsmouth (now Portsmouth Cathedral), included transferring the remains from all of the brick graves in the main body of the church to a new purpose-built vault in the north-east corner of the building. ‘The work had only gone on for two days when the stench from the open vaults, polluted soil and decomposing remains became so overpowering that the Medical Officer of Health, Dr A. Mearns Fraser, inspected the works and ordered the closure of the church.35 In mid-December the Revd Charles Darnell, vicar of St Thomas, was taken ill with typhoid fever, with septicaemia intervening. All efforts to save his life were fruitless and he died on 6 January 1903.’36 Regulations for the exhumation of human remains are very strict today, and are described in the section on Spitalfields in chapter 3.

WHAT IS TODAY’S VALUE OF THE SUMS GIVEN FOR FEES AND SALES?

To calculate this I have used the Bank of England’s Inflation Calculator (1750–2012), and the 2012 value has been put in brackets after the sum quoted. The sums paid for church sites are listed in the Appendix.

WHERE WERE THE HUMAN REMAINS REMOVED TO?

A minority went to the East London Cemetery, Plaistow, or to the Great Northern London (now New Southgate) Cemetery. Some relatives were allowed to take the coffin of a family member to a burial ground of their choice, but most were taken to Brookwood or Ilford.

Brookwood, Surrey

At the end of 1849 Richard Sprye and Sir Richard Broun decided to provide a ‘City for the Dead’ at such a distance from the metropolis that it would never be part of the capital. Edwin Chadwick was not enthusiastic, and in an undated angry letter to Blomfield referred to ‘a large new trading job, the Woking scheme, vulgar projections, a vulgar architect trying to get a Bill for the purpose and to make a market with the parishes’.37 Some 2,200 acres of land owned by Lord Onslow on Woking Common at Brookwood were duly purchased by the newly formed London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company. Despite opposition Royal Assent was given to the London Necropolis Bill on 30 June 1852, but the first funeral was not held there until 13 November 1854. Soon afterwards several Westminster parishes, including St Anne Soho, St Giles-in-the-Fields and St Margaret Westminster, reserved plots there. Unusually, interments at Brookwood could take place on Sundays, which was an added advantage.

A coffin being loaded into a hearse van on the train to Brookwood, c.1905. The funeral party has probably just emerged from a private waiting room on the left.

The Necropolis train en route to Brookwood, passing Wimbledon, on 25 June 1902. The hearse vans are the third and last coaches.

St Magnus the Martyr. Fallen obelisk 1893–94 at Brookwood. (The plot contains 534 cases of remains.)

Coffins and mourners were transported by special trains from a private terminus near Waterloo to the cemetery’s two stations, one for Anglicans and one for others.38 Addressing the 1842 Select Committee, the bishop had already suggested that a railway should not be used to transport the funeral party because few were used to it, and the ‘hurry and bustle’ was ‘inconsistent with the solemnity of a Christian funeral’. He also found the idea of assembling a number of funerals from widely social backgrounds in the same conveyance ‘offensive’. ‘It might sometimes happen,’ he told members, ‘that the body of some profligate spendthrift might be placed in a conveyance with the body of some respectable member of the church, which would shock the feelings of his friends.’39 The bishop would certainly not have approved of the notice in the station refreshment room at Brookwood: ‘Spirits served here’.40

It was originally thought that the cemetery would be sufficiently large to contain all London’s dead forever, and Dr Sutherland of the Home Office estimated that the 60,000 who died each year in the 1850s could be accommodated in separate graves in perpetuity. It is estimated that 80 per cent of the Brookwood interments were of paupers, and each year Necropolis tendered for the burial of the poor from London parishes who often, as at St Giles-in-the-Fields, left the location to be decided by Necropolis.41 This meant that most of the middle classes were not attracted to Brookwood, and Necropolis succeeded in attracting only a small proportion of metropolitan burials: in the twenty years after consecration the average annual number of interments there never exceeded 4,100.42

Sadly the plots purchased by the City and Westminster parishes at Brookwood are now an overgrown wilderness, with the memorials in a parlous condition. Fortunately in the last ten years the picture has begun to change thanks to the formation of a Friends organisation, and priority is being given to green areas.43

City of London Cemetery, Ilford

In 1848 the City Corporation appointed Sir John Simon as its first Medical Officer of Health, and he persuaded the corporation to purchase their own burial ground. In 1853 he recommended that ‘a very eligible site’ of 200 acres at Aldersbrook Farm near Ilford be acquired.44 Opened in 1856 and approximately 8 miles north-east of the City, this cemetery was used by nearly all the City parishes once the Corporation’s Commissioners of Sewers became the Burial Board for the Square Mile under the 1852 Burial Act. Recompense was agreed with the incumbents and a chaplain appointed. This did, however, mean that the City vestries, unlike those in Westminster, lost control of burial provision. Since then over forty City parishes have removed crypt remains to Ilford, which is today one of the most beautiful cemeteries in Great Britain.45

Holy Trinity the Less. City of London Cemetery. House Tomb with decorated tracery, 1872. (The plot contains remains from the churchyard.)

IS THERE A MORAL DILEMMA IN EXHUMING BODIES?

Can the Church justify clearing the remains of those whose relatives paid dearly for a place of ‘perpetual’ deposit in the vaults? In taking money a contract was established, so what restitution, if any, should descendants of the deceased expect? Burial in a churchyard or municipal cemetery was precisely what these relatives were trying to avoid through purchasing a vault. Should human remains be disturbed? In the Middle Ages the Church often had no compunction in disturbing burials and putting bones in a charnel house, and this continued into the eighteenth century. Parish councils planning a clearance might consider cremating the remains and placing the ashes below the crypt floor, as happened at St Clement Danes and St Mary-le-Bow, or they might stack coffins in one area and wall them up.