Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

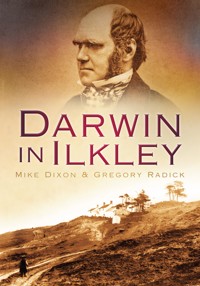

When the Origins of Species was published on 24 November 1859, its author, Charles Darwin, was near the end of a nine-week stay in the remote Yorkshire village of Ilkley. He had come for the 'water cure'- a regime of cold baths and wet sheets - and for relaxation. But he used his time in Ilkley to shore up support, through extensive correspondence, for the extraordinary theory that the Origin would put before the world: evolution by natural selection. In Darwin in Ilkley, Mike Dixon and Gregory Radick bring to life Victorian Ilkley and the dramas of body and mind that marked Darwin's visit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Darwin In Ilkley

Darwin In Ilkley

Mike Dixon & Gregory Radick

For Mark, Jane and Anna DixonandBen and Matthew Radick

First published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

©Mike Dixon & Gregory Radick, 2009, 2013

The right of Mike Dixon & Gregory Radick to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5266 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

About the Authors

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter One: First Impressions

Chapter Two: The Lord Chancellor’s Verdict

Chapter Three: Illness and the Water Cure

Chapter Four: The Malvern of the North

Chapter Five: Problems with Progress and Pallas

Chapter Six: North House

Chapter Seven: Smoothing the Way

Chapter Eight: Publication and Publicity

Chapter Nine: A Medical Postscript

About the Authors

Mike Dixon is Emeritus Professor of Gastrointestinal Pathology at the University of Leeds and has lived in Ilkley since 1970. In parallel with a distinguished clinical and academic career in Pathology, he pursued a keen interest in local history. The introduction of hydropathy and the Victorian development of Ilkley are particular interests, and through them he came to study the town’s most illustrious water cure patient, Charles Darwin. This involvement in local history has led to the publication of Images of England: Ilkley (1999) and Ilkley – History and Guide (2002).

Gregory Radick is Senior Lecturer in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Leeds and has lived in Ilkley since 2000. His interests as a historian have centred on Darwin’s theory of evolution, its historical contexts and its legacies within and beyond biology. Previous books include The Simian Tongue: The Long Debate About Animal Language (2007) and, as co-editor (with Jonathan Hodge), The Cambridge Companion to Darwin (second edition, 2009). Currently he is researching the early years of Mendelian genetics.

Preface

On 4 October 1859, Charles Darwin arrived in Ilkley to take the ‘water cure’. At that time, Ilkley was no more than a village, similar to many others in the old West Riding of Yorkshire but distinguished from them by its hydropathic establishments. Darwin stayed for just nine weeks; but it was during this visit that his famous book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection was published. A man who was already recognised as a gifted naturalist and scientific voyager was on the verge of becoming one of the most influential, celebrated and controversial figures of all time. The publication of the Origin on 24 November 1859 marked the start of Darwin’s new identity as a theorist of evolution.

Darwin’s visit to Ilkley attracts only brief mention in recent biographies.1 Yet the visit coincided with an important period in Darwin’s life. During his time in Ilkley, he had to cope with chronic illness and the rigours of the water cure, make the final corrections to the text of the Origin, and manage the reception of a book that he had come to refer to as his ‘abominable volume’.2 We shall examine the scenes of all this intense activity: Wells House Hydropathic Establishment, including the treatments, amenities and Darwin’s fellow guests; the social life of the Hydro and his participation in it; the austere surroundings of North House, a temporary residence made bearable by the presence of his family; and Ilkley itself, rustic and inaccessible, but a Northern Mecca for the ‘water patient’.

That Darwin came to Ilkley to undergo the water cure raises intriguing questions. How was it that a man of his scientific calibre was drawn to a treatment that many at the time considered to be quackery? Why did he feel compelled to travel over two hundred miles from Down House in Kent to a village in Yorkshire to undergo this treatment, which was available much closer to home? In answering these questions, we will also consider the mysterious nature of Darwin’s illness and the well-documented failure of orthodox treatments. Darwin’s experiences of the water cure regime in Ilkley turn out to disclose evidence that, we suggest, may allow a final settling of the debate over what ailed him.

Attention to Darwin’s life in Ilkley likewise throws new light on the intellectual run-up to the Origin’s publication. The unparalleled examination offered in these pages of Darwin’s Ilkley correspondence reveals a mixture of trepidation at the book’s likely reception and assertiveness over the correctness of his theory. Against the backdrop of the moor, Darwin took part in one of the most challenging debates that he would ever enter into over the Origin, touching on everything from whether he had relegated God to an implausibly small role in the making of new species to whether domesticated dogs have more than one wild ancestor (a politically charged question at that moment).

Taken together, these reconstructions give us a composite portrait of a man who, far from the cringing recluse of legend, comes across here as warm, convivial and socially and intellectually confident. Yet for all that Darwin is at the centre, the book is also a work of local history. From 1859 onwards numerous hydropathic hotels were opened in Ilkley, leading to an upsurge in visitors and providing additional employment. The hotels also encouraged an expansion of shops and services in the town, and the population grew – albeit slowly at first. Rapid growth followed the opening of the railway lines to Leeds and Bradford in 1865. Thus at the time of Darwin’s visit, Ilkley was in its last years as a minor spa. Over the next decade, its new transport links and a marked increase in house building would change it into a commuter town, as well as a fashionable inland resort.

We feel, therefore, that it is both fitting and timely to give a detailed account of Darwin’s short but eventful visit to a small Yorkshire village that was itself on the cusp of ‘transmutation’.

Notes

1 In Bowlby, J., Charles Darwin:A New Life (W.W. Norton & Co., New York 1991) less than two of 466 pages of text are devoted to the Ilkley visit, and in Desmond, A., and Moore, J., Darwin (Michael Joseph, London 1991) there are just over two of 677 text pages on the subject. In her biography, Janet Browne gives a more detailed account but this only extends to eight of 497 text pages in the second volume of her two-volume work, (Browne, J., Charles Darwin: The Power of Place, Jonathan Cape, London 2002).

2 ‘So much for my abominable volume, which has cost me so much labour that I almost hate it’, C.D. to W.D. Fox, 23 Sept 1859; Correspondence (see Abbreviations, p. 10).

In the published Correspondence the date of the letter is given in a standard form, but those elements not taken directly from the letter text are supplied in square brackets.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank:

Dr Roger Pyrah of Skipton, who in May 1988 first alerted Mike Dixon to Charles Darwin’s visit to Ilkley, and for his continuing interest in Darwin’s illness.

Alex Cockshott for information regarding Wells House and Wells Terrace, and the photograph of Marshall Hainsworth. Dennis Warwick and Brian Clayton for genealogical information concerning the Hainsworth family, and Jean Hawley and Anne Sanders for information concerning South View and Laburnum Cottage.

Colin Clarkson for access to the title deeds of Rombald’s Hotel and maps relating to its period as Usher’s boarding house.

Peter J. Adams of Heritage Cartography for permission to publish the map of Ilkley in 1859, modified from his 1847 version.

The late Kate Mason for details relating to White Wells in the Addingham records, and the late Chris Hellier of the Museum of Farnham for information relating to Moor Park, Surrey.

Thanks are due to the staff of Ilkley Public Library, to Kathryn Emmott, Sandra Hanby and the late Roland Wade for photographs, and to May Pickles for the etching of Ben Rhydding Hydro. We are particularly indebted to the late Gordon Burton and his wife Betty, for the loan of items from his unique collection of old Ilkley photographs. All unattributed photographs are from Mike Dixon’s collection.

Finally we wish to thank Gerry Shaper for spurring us to action in time for the anniversary of Darwin’s visit to Ilkley, and Lindsay Gledhill, Jon Hodge and Jo Lawton for their perceptive and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

We have used the following abbreviations in the sources and notes at the end of each chapter:

C.D. – Charles Darwin

Autobiography – Nora Barlow, Ed. The autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, with original omissions restored. (Collins, London: 1958).

Correspondence – Frederick H. Burkhardt, Sydney Smith, et al., Eds. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, vols 1 – 14 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1983-2004).

DCP – Darwin Correspondence Project; www.darwinproject.ac.uk. This source is used for recently discovered letters that do not appear in the published Correspondence. Each letter in the catalogue has a unique identifying number.

Life and Letters – Francis Darwin, Ed. The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin. Vols. I-III (John Murray, London: 1887).

Journal – Darwin’s personal ‘Journal’ (Cambridge University Library DAR 158) is available online (www.darwin-online.org.uk) but has also been transcribed and reproduced as appendices (‘Chronology’) in the published volumes of Correspondence.

Chapter One

First Impressions

I am in the establishment & have a sitting room and bedroom. I always hate everything new & perhaps it is only this that makes me at present detest the whole place & everybody except one kind lady here, whom I knew at Moor Park. – It would be excessively nice if you were to come here for a time. Dr Smith, I think, is sensible, but he is a Homoeopathist!! & as far as I can judge does not personally look much after patients or anything else. – There is a capital steward & the House seems well managed.1

So wrote Charles Darwin from Wells House Hydropathic Hotel on Thursday 6 October, two days after his arrival in Ilkley. His correspondent, the clergyman and naturalist William Fox, was a close friend from his Cambridge days (indeed a second cousin), now living in Cheshire – at that time, about five hours journey from Ilkley. These opening lines in Darwin’s first surviving letter from Ilkley touch on two key elements of his visit: the hotel itself, and the people he encountered there.

Built three years before Darwin’s visit, Wells House still stands, having recently been converted into apartments. The building occupies a prominent position 300ft above the centre of Ilkley. When the hotel was built, Ilkley was little more than a small collection of streets and houses straddling the main Otley to Skipton turnpike on the south side of the River Wharfe. Wells House was not the first hydropathic hotel to be built in the Ilkley area. That distinction goes to Ben Rhydding Hydropathic Hotel, opened in 1844, an even larger edifice a mile down the valley. By the late 1840s, Ben Rhydding was seen to be manifestly successful. The owner, Dr William MacLeod, was a charismatic figure who had established a considerable reputation for his ‘water cure’, and large numbers of patients visited the establishment – the first purpose-built hydropathic hotel in England.2

Others sought to follow his example, but the lack of availability of suitable building sites put a bar on such developments. Apart from smallholdings in the centre of the town, much of the land in Ilkley was in the ownership of the hereditary Lords of the Manor, the Middeltons. Successive Lords of the Manor had resolutely opposed any sale of land, but by 1850 the family were facing serious financial difficulties and they became more receptive to such proposals. In October that year, the then Lord of the Manor, Peter Middelton, was approached by the representative of a group of ‘commercial gentlemen’ with an offer to purchase nine acres of land at the top of Wells Road.3 The land comprised two large fields – Little and Great Intake4– surrounding a dilapidated former cotton-mill (by then converted into three shabby cottages rented by the Hodgson family).5 Since the annual rent from the land and cottages only amounted to £14, the offer of £4,000 by the joint-stock company was a bargain too good to miss. Thomas Constable, the Otley solicitor acting for the Middeltons, urged acceptance of the offer, ‘not only because £4,000 is an enormous price for nine acres of inferior hillside land, but still more because the establishment will be tenanted by wealthy and numerous occupiers whose wants will greatly enhance the value of all the adjoining property’. Peter Middelton was persuaded but, partly as a consequence of conveyancing difficulties, the transaction was not finalised until 8 June 1854.6 In order to secure a plentiful supply of pure water for their hydropathic hotel, the developers also purchased a direct supply from the spring behind the old bath-house, White Wells, on the hillside above the site of the proposed hotel. Spring water was diverted via an underground cistern near the bath-house and then led underground through a 1in diameter pipe down to the hotel.7

Above: Wells House in June 1860 with a more accurate representation of the approach and main entrance to the hotel. The east terrace, which contained the treatment rooms beneath it (accessed at basement level from the hotel), is clearly shown.

Right: Ben Rhydding Hydro, Ilkley’s first hydropathic hotel, was built high above the then hamlet of Wheatley beneath the Cow and Calf Rocks. (May Pickles)

The developers had their land and a water supply, now they set about appointing an architect. In a bold and inspired choice, they settled on a young Leeds architect, Cuthbert Brodrick, who already had one magnificent design in his growing portfolio – Leeds Town Hall. Indeed, building of the Town Hall was in progress when he undertook to design the hotel in Ilkley. Brodrick was brought up in Hull, and at the age of sixteen (in 1837) was apprenticed there to a highly successful practice belonging to Henry Francis Lockwood. In 1845 he set up his own practice in Hull and was responsible for several local projects, including the splendid Royal Institution building completed in 1854. Two years earlier, he had won an open competition for the design of Leeds Town Hall – with a prize of £200 – and had moved his office to Park Row in Leeds.8 Despite his comparative youthfulness, Brodrick was a highly sophisticated architect. During his years in Hull, he took several months leave of absence to undertake a ‘Grand Tour’ of the European capitals. This exposure to continental influences was to inform his designs in ways that were beyond the experience of his provincial competitors.9 His design for Wells House embodied much of his flair for restrained grandeur. The style revealed Brodrick’s Italian influences, being reminiscent of a palazzo in the form of a square with towers at each corner and a central courtyard. Unfortunately, his restraint in design did not extend to the cost. The completed project cost in the region of £30,000, equivalent to at least £3 million pounds in today’s values.

Ilkley from the Cow Pastures, 1855. This artist’s impression shows a rustic village with little of note apart from the tower of the parish church and the large house on the opposite hill side – Myddelton Lodge, home of the Lord of the Manor. The houses on the left mark the line of Wells Road leading up to the moor and to Wells House.

By February 1856, the directors were sufficiently confident about their scheme to issue a ‘news story’ via the Leeds Mercury:10

Ilkley Wells:- To many of our readers these words bring to mind an irregular whitewashed building, about half way up the hills above Ilkley, containing two formidable looking wells, or plunge baths, into which the strong minded searchers after health have been in the habit of immersing themselves and their families these hundred years and more. But time works wonders – for now, when he hears of “Ilkley Wells,” instead of associating this humble though venerable pile, the reader must picture to himself a stately edifice, a veritable Italian palace, which now claims that name, and which, during two years past, has been gradually rearing its towers above the lovely valley of the Wharfe. Health and relaxation, cold water and creature comforts, appear to have been the object in view with the projectors of this bold undertaking.

Wells House was built close to the foot of the donkey track leading up to the old bath-house on the moor, White Wells. Guests with a south-facing bedroom would have enjoyed a view similar to this.

The building is designed for a hydropathic establishment and hotel, and, truly, the votaries of hydropathy and the frequenters of watering-place hotels may search far and wide before they find a resting-place to compare in architectural effect with this noble structure. It stands not very far distant from the Old Wells, which still remain to assert their ancient title, and which share with it the waters of their crystal spring. The situation is thus very happily chosen, as all frequenters of Ilkley will know, who remember the charming views from this position on the hill. If pure cold water and free bracing air can do much towards restoring health, certainly the new Hydropathic Establishment will be in possession of two important remedies; and summer tourists will have another object added to the list of attractions in hill and valley scenery... At present the place presents a busy scene of preparation, both in the house and grounds, but it is said that all will be complete in readiness for the approaching season.

The building was completed by May 1856. The elevated site (Wells House is 517ft above sea-level) had two main advantages; firstly, the ‘bracing air’ at this height was claimed as an important adjunct to the water cure regime, and secondly, the building formed a striking feature of the landscape and could be seen from almost everywhere in the vicinity. The main entrance was on the south side facing the moor, and a curved drive led down to the extended Wells Road, a road linking it directly to the centre of the town. The house was surrounded by gardens laid out by the celebrated landscape gardener Joshua Major, who had been responsible for the design of Manchester’s first three municipal parks.11 In addition to decorative flower beds and paths, many trees and shrubs were planted, and lawns laid out for tennis and croquet. Two small lakes opposite the entrance of the hotel completed the scene.

The hotel had its own stables, which were built on the site of the old cotton mill. The stalls for the horses and storage accommodation for the carriages were arranged around a large central yard whose entrance was flanked by two cottages, a porter’s lodge and a house for the gardener.

Internally, no expense had been spared in the furnishing and equipping of the bedrooms and public rooms. The hotel had ‘a dining room capable of seating between 80 and 100 guests, a large public drawing room, a private drawing room for ladies only, and a coffee room for general visitors or those not wanting to join the company at the table d’hote, a billiard room, thirteen private sitting rooms, eighty-seven bedrooms and six bathrooms’.12 Although viewed from our perspective the number of bathrooms seems grossly inadequate, the Victorian hotel relied on bedrooms having movable, rather than plumbed-in fittings. The usual practice was to wash or bathe in one’s own room, and on request a chambermaid would bring hot water to fill a bowl on the wash-stand or provide a hip-bath. Likewise, a midnight hike to some distant lavatory was circumvented by use of the bedside commode.

The hotel corridors were spacious and well-lit. Walking around the corridors formed a valuable alternative to outdoor exercise when the weather was poor – an essential facility in Ilkley. The treatment rooms occupied the extensive basement under the terrace on the east of the building. They contained a variety of baths, douches, massage and wet-sheet tables. The marble walls and the richly patterned tiles provided a suitably opulent backcloth for the watery arts of the hydropathic practitioner.

The building was officially opened on 28 May 1856 when ‘about 150 ladies and gentlemen partook of a sumptuous collation, most tastefully served in the large dining hall, under the direction of the manager, Mr Strachan. To enliven the proceedings the band of the North York Rifles played during the splendid repast’.12 The host at this celebratory meal was the chairman of the board of directors, a redoubtable Bradford wine and spirit merchant, Benjamin Briggs Popplewell.13 The ‘top table’, which must have been a long one, was made up of fellow directors and their wives, civic dignitaries, clergymen and people otherwise connected with the enterprise, like Cuthbert Brodrick and the Middelton’s solicitor, Thomas Constable.14

Wells House Stables. One of the two cottages that flanked the entrance to the stable yard, photographed in the 1890s. The cottage, ‘Ivy Lodge’, has been enlarged recently and is now a private house.

Wells House Stables. The yard, with a ‘four-in-hand’ carriage occupying pride of place.

The staircase leading from the ground floor of the hotel down to the baths and treatment rooms situated below the east terrace. Photograph taken in 1999, prior to the redevelopment of the building and conversion into apartments. (Kathryn Emmott)

Ground floor corridor in Wells House photographed in the 1930s.

Despite this ambitious start, all did not go well for Mr Popplewell and his fellow directors. Guests were not attracted in the numbers required and the enterprise was soon in financial difficulties. Some of the blame was levelled at the resident physician, Dr Antoine Rischanek, a ‘water-doctor’ from Vienna who had presided over a similarly unsuccessful period after the opening of Ben Rhydding Hydropathic Hotel. Two years after his appointment there, he had been dismissed and, after a year’s inter-regnum, replaced by Dr Macleod, who had gone on to make such a success of the place.14 Now, Rischanek was to suffer a similar fate. He departed in April 1858 and was immediately replaced by a doctor from Sheffield with an interest in hydropathy, Dr Edmund Smith. As at Ben Rhydding, Rischanek’s replacement appears to have turned around the fortunes of the place. By the summer of 1859, the hotel, and its physician, had managed to acquire a good reputation.

Benjamin Briggs Popplewell, Bradford wine and spirits merchant and chairman of the directors of the Wells House Hydropathic Establishment.

The main dining room photographed in the 1930s. In the Victorian era, the diners would have sat at long, refectory-type tables.

But Darwin was not much impressed by reputation, and the discovery that Dr Smith was a homoeopathist would have irritated him. He had a deep-seated antagonism towards homoeopathy – the administration of minute amounts of drugs in order to excite symptoms similar to those of the disease to be treated. Writing some years before to his Cheshire cousin Fox, Darwin made his views clear:

You speak about Homoeopathy; which is a subject which makes me more wrath, even than does Clair-voyance: clairvoyance so transcends belief, that one’s ordinary faculties are put out of the question, but in Homoeopathy common sense & common observation come into play, & both these must go to the Dogs, if the infinitesimal doses have any effect whatever.15

Edmund Smith practised for many years as an ‘orthodox’ medical practitioner before turning to homoeopathy. He had previously worked as a surgeon in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, and then acquired a medical practice in Sheffield.16 The date of Dr Smith’s ‘conversion’ to homoeopathy is not recorded but he is listed in the British Journal of Homoeopathy in 1850 and in the British and Foreign Homoeopathic Medical Directory and Record of 1855.17 In 1858, he was created M.D. by the Archbishop of Canterbury – a so-called ‘Lambeth degree’, given in recognition of his medical experience but also an acknowledgement of his services to the Church of England. As regards his medical expertise, Dr Smith was not a shining example of the efficacy of either homoeopathy or the ‘water cure’, for he suffered chronic ill health and was debilitated throughout his time in Ilkley.18 This could explain Darwin’s observation that Dr Smith ‘does not personally look much after patients or anything else’.18

Although the directors of Wells House had appointed Dr Smith as ‘Medical Director and Manager’, the latter title held an ambiguity.19 Smith managed the patients but the hotel was managed by Henry Strachan, a man with over ten year’s experience as House Steward at Ben Rhydding before joining the staff at Wells House.20 Given that Darwin considered the place ‘well managed’, Strachan must have run a ‘tight ship’. Wells House required the usual hotel personnel including a general housekeeper, a cook, kitchen maids, porters, waiters, chambermaids and gardeners, together with the male and female bath-attendants required for the hydropathic treatments.21 The latter had to be carefully chosen. An air of decorum had to be maintained in the treatment rooms and, to this end, the attendants had to be mature and discreet. Female bath-attendants had to be ‘respectable’, ‘not less than thirty years of age’ and ‘have had considerable experience’.22

Despite all this attention to detail, Darwin’s initial reaction, as we have seen, was to ‘detest the whole place’. Given the facilities at Wells House and the beauty of its setting, this must have been a highly unusual response. Darwin, however, was a highly unusual visitor. Over many years, he had become increasingly anxious when meeting new people, and by his own admission found social gatherings an ordeal. ‘I find by dear bought experience that I cannot visit anywhere, as the excitement invariably does me harm for days afterwards’.23 He wrote in 1852 of leading the life of a hermit,24 and a year earlier had confessed that ‘I very seldom leave home, as I find perfect quietude suits my health best’.25 Darwin generally only left Down House (his home in Kent) reluctantly, and then in the company of his wife; he carefully controlled the number of visitors he saw, and normally shunned conversation with those outside his circle of family and close friends.26

Given this psychological background, it was no less than heroic for Darwin to make the solitary journey to Ilkley and to place himself in a large hydropathic establishment with its unappealing clientele, the sick and suffering of the upper-classes – the effete, the neurotic, the halt and the lame. Certainly the prospect filled him with foreboding. It was no doubt this dread of a house filled with strangers that prompted him to write to Miss Mary Butler, the ‘kind lady’ who had made an impression on him when he had stayed at Moor Park, a hydropathic establishment in Surrey, earlier that year.

Mary Butler was a charming Irish woman who regaled fellow guests at Moor Park with witty conversation and ghost stories.27 She appears to have quickly won Charles Darwin’s attention when he stayed there in February 1859. This is unsurprising; Darwin’s weakness for attractive younger women was well known to his family. His son Francis Darwin recounted:

He was particularly charming when “chaffing” any one, and in high spirits over it. His manner at such times was light-hearted and boyish, and his refinement of nature came out most strongly. So, when he was talking to a lady who pleased and amused him, the combination of raillery and deference was delightful to see.28