Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

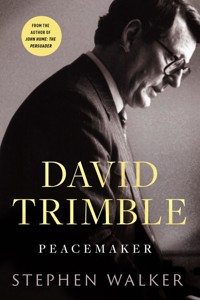

Nobel laureate, party leader, peacemaker, first minister and statesman – David Trimble had many roles. But what is the real story behind the man who made headlines and changed lives? In this definitive biography of Trimble's life and death, award-winning journalist Stephen Walker vividly details how a shy Belfast academic changed the political landscape of Northern Ireland. Written with the cooperation of his widow, Lady Trimble, and their grown-up children, Peacemaker offers unparalleled insights into the life of the first person to be elected first minister of Northern Ireland and the most significant unionist leader since the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921. From the beginning of his political career in the dark days of the Troubles, to bringing unionism and nationalism together to end decades of division and violence and secure peace, Trimble's personal journey mirrors the story of Northern Ireland itself. Drawing on over 100 fresh interviews, this is a colourful and personal account of the life of a key figure in Irish history and an essential companion to Stephen Walker's bestselling biography of John Hume.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 741

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DAVIDTRIMBLE

PEACEMAKER

STEPHEN WALKER

GILL BOOKS

For Katrin, Grace, Jack and Gabriel.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

1Bangor boy

2First among equals

3Vote Trimble

4Bringing down the house

5Breaking the Convention

6Hello, Daphne

7To have and to hold

8Murder in the morning

9The wilderness years

10Goodbye, Queen’s

11Snowballs and secret talks

12Stalking and walking

13Follow the leader

14New Labour, new ideas

15The final countdown

16Deal or no deal

17Just say yes

18From Omagh to Oslo

19Guns and government

20Stop start Stormont

21Hearts and minds

22Spies, splits and suspensions

23A good innings

24The final days

25Portrait of a peacemaker

Sources

Bibliography

Endnotes

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright Page

About the Author

About Gill Books

Advance Praise for David Trimble: Peacemaker

Photo Section

PROLOGUE

Castle Buildings, Stormont Estate, BelfastGood Friday, 10 April 1998

The door was locked. No one was coming in and no one was leaving.

For David Trimble and his party, it was decision time. The Ulster Unionist Party leader and his inner circle had much to discuss.

In the cramped, airless room, there was a groundbreaking deal to be considered. The pressure was intense.

Hours before, in the grounds of Stormont, there had been raised voices from Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party, who believed a sell-out was on the cards. Paisley, Ulster’s ‘Dr No’, so long the voice of uncompromising unionism, opposed power-sharing and had boycotted this round of talks.

He and his supporters had branded Trimble a traitor, while others had used the term ‘Lundy’ – a reference to Robert Lundy, who famously betrayed Protestants during the Siege of Derry in 1689.

As the talks process entered its final stages, Paisley had turned up to protest and demand that his main unionist rival should walk away.

Trimble was going nowhere.

Over the past 24 hours there had been no shortage of advice for the UUP leader, and calls to his mobile phone were constant. Prime Minister Tony Blair and Taoiseach Bertie Ahern had urged him to endorse what was on the table. They told him it was a good deal, and the agreement would deliver what he wanted. The two premiers argued that it was a historic agreement that could end Northern Ireland’s long-running political stalemate, cement Northern Ireland’s place in the UK, create a new cross-community government and change British and Irish relations.

It was a compromise, and Trimble was being urged to say yes. He knew what the deal could potentially deliver. This was an opportunity for peace. It was not perfect, and there was still much detail to be confirmed, but he believed it represented a fresh start. For the first time in a quarter of a century, politicians with different identities would share power at Stormont. The figureheads of this new administration would be a unionist and a nationalist.

On a personal level, Trimble knew that if this deal was endorsed by voters, he would become Northern Ireland’s inaugural first minister. He also knew it presented the opportunity to become the most important unionist leader since the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921. A student of the past, Trimble knew all that. Yet, he was not interested in making history for history’s sake. He wanted the agreement to be the best he could reach, and he felt it required improvements.

With the clock ticking, he needed some space and did not want to be disturbed or distracted. Away from the spin and the high-pressure sales talk, he had to gauge what his colleagues really felt.

The deadline had expired.

The former US senator George Mitchell, the American talks chairman, had made it clear that there would be no extra time. These were the final minutes. After 700 days of talking, the negotiating was over. Trimble’s team, like those of the other parties, were exhausted.

Some had slept on floors and chairs in adjoining offices as they read and re-read the deal. Some had no sleep at all. Trimble needed to get them to focus.

Key questions remained for unionists. Did the deal enhance and protect the union with the rest of the UK? Was the union stronger than when Trimble and his team began to negotiate? There were other big issues to consider. What would the unionist community make of the reforms to policing, the early release of prisoners and the issue of decommissioning?

As Good Friday wore on, the UUP leader desperately needed one more thing. Trimble said he would go back to the UK government on a single issue and asked his colleagues what that should be. They all agreed there must be a stronger link between the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons and Sinn Féin’s participation in a power-sharing government.

For the rest of the afternoon, Trimble and his colleagues shuttled between meetings with Tony Blair and his advisers. They made it clear to Blair that without a stronger commitment on decommissioning the Ulster Unionists could not support the deal. By that time, the other parties were getting restless and became aware of the UUP’s difficulty. A novel plan was then hatched by the British government. Blair agreed that he would write Trimble a letter to reassure him that he would support the exclusion of Sinn Féin from government if there had not been any weapons decommissioning. Downing Street also asked Bill Clinton to help, and the US president rang the UUP leader and urged him to endorse the agreement.

As Trimble and his colleagues continued their deliberations, Blair’s chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, finished typing the letter on his laptop and went in search of the Ulster Unionist leader.

When Powell arrived at the UUP room he could not get in as it was locked. He quickly managed to attract the attention of a young unionist near the door and, once he was inside, the letter was passed to Trimble.

The UUP leader opened the envelope and read Blair’s words, with John Taylor, the former Stormont home affairs minister, looking anxiously over his shoulder. Taylor was quick to finish reading the short message and then declared, ‘That is fine, we can run with that.’ It was now game on.

At 4.46 p.m., Trimble lifted the phone to Mitchell. He told the talks chairman, ‘We’re ready to do the business.’ Trimble was now able to do something that no unionist had ever done: to agree to a multi-party administration at Stormont that involved unionists, nationalists and republicans.

For Trimble, it represented another remarkable step in his political journey. Having been a hard-line street protestor who opposed the last attempt at cross-community government at Sunningdale, he was about to endorse power-sharing. As an outspoken Orangeman, he had once walked hand in hand with Ian Paisley in Portadown. Yet now, he was plotting his own course. When he was at Queen’s University, he had missed out on promotion three times. Now, he was the front-runner for the most powerful job in Northern Ireland, and within months he would become a Nobel laureate.

As he prepared to make his decision public, the media were waiting. For days they had chronicled the twists and turns of a process that at times seemed pointless and ready to collapse. Wasn’t that always the narrative? In the reportage of Northern Ireland, the words ‘talks’ and ‘failure’ were often part of the same sentence. Amongst the pockets of seasoned reporters were many who had covered Northern Ireland’s bloodied past. Days painfully etched in their memory – anniversaries that were synonymous with pain. Bloody Sunday, Bloody Friday, the Poppy Day bombing in Enniskillen, Halloween night in Greysteel. The list was long and filled with heartache.

So, was all that about to change? Was Northern Ireland about to witness a new chapter? Were the leaders of unionism and nationalism really committed to sharing power – nearly a quarter of a century after the last attempt?

Beyond the perimeter fence amidst the television satellite trucks and temporary buildings the word had spread that an announcement was coming.

The deal was done and reporters and producers readied themselves for interviews. It had been a most unusual day in so many ways.

Even the weather was defying predictions. The sun had shone, it had rained and now it was trying to snow. Northern Ireland in April. Four seasons in one day.

Inside Castle Buildings, 53-year-old William David Trimble was about to make history and say he was ready to preside over a new form of power-sharing government. He began the negotiations as an MP and party leader, but he was about to get a new title: first minister.

For the politician and peacemaker, life would never be the same again.

1

BANGOR BOY

‘His work is dirty, carelessly set out and his compositions are so full of ridiculous mistakes that often it is not worth marking.’

David Trimble school report, 1955

David Trimble was running for his life. His would-be attacker was armed with a hatchet and seemed pretty intent on causing him harm. David had the advantage of being a few paces ahead of his assailant and knew if he could just reach the sanctuary of his house, he would be safe. He sprinted and made a beeline for the glass-panelled back door, which was at the side of his house.

In the summer months it was used all the time and was normally kept wide open. As David reached the house, he quickly pushed his body forward.

On this occasion the door was surprisingly shut, and the momentum resulted in his arm going straight through the glass. There was a scream, followed by blood and tears. Pandemonium broke out. It was not meant to end like this. His pursuer was none other than his younger brother Iain. He and his sister Rosemary had been playing in the back garden of their Bangor home when David had surprised them and had tried to frighten them by pretending to be a scary monster. Iain’s decision to fight back ended badly, leaving his brother with scars that he would carry for the rest of his life. Their parents were understandably furious that an innocuous bit of fun had ended in such a horrific way. Iain was told that he had behaved badly and recalls that he was punished for his behaviour and remembers being ‘in the doghouse for ages’.1

The incident did not damage his relationship with his brother, however. In later years, often over a glass of wine, the two men would make light of that dramatic day. David would be characteristically blunt: ‘Iain, do you remember the day you tried to kill me with a hatchet?’2

Iain may have been the villain on that occasion, but there were other times when David’s temper got the better of him. David recalled getting cross on one occasion:

I do remember when I was aged about five having an argument with another person and he got me so angry that I put my head down and ran at him. The other lad of course did the smart thing and stepped to one side, and I ran straight into a wall.3

This may be the first time the famous Trimble temper was aired in public. However, it was something his brother Iain would become well used to. The two boys were born four years apart. David was older, having been born in Belfast on 15 October 1944, while Iain was born on 14 December 1948 in Bangor. They got on well together, so much so that Iain was David’s best man when he married Daphne Orr in 1978. Yet, the two brothers were very different. David was shy, awkward and bookish, with no interest in sport. He was the more intellectual of the two:

I remember a teacher saying, ‘You’re David’s brother, aren’t you?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ ‘Oh,’ came the reply. And then there is an expectation which I could never fulfil because I am not that bright.4

Iain clearly looked up to his older brother. While they played together as kids, it was clear David was perfectly happy in his own company.

He had a room of his own, you never saw him, except for meals. He was in his room reading. He got told off time and time again for reading in the middle of the night by candlelight.5

Rosemary, the eldest, was born on 8 April 1943 in a private nursing home in Belfast. She got on well with her brothers:

We had plenty of room. We had a big garden at the back and a garden at the front. There was grass and fruit bushes, raspberries and gooseberries. We had lots of fun, chasing each other and playing all sorts of games. It was idyllic.6

Like Iain, Rosemary remembers David would disappear and often go and sit alone. She recalls how he was happy in his own company, but if he was missing he would be easy to locate. ‘If you could not find David, you would find him with his nose in a book.’7

Their parents were Billy and Ivy, although Ivy was not her original name. She was going to be called Annie Margaret Elizabeth, which were the names of three great aunts. Her mother, David’s grandmother, could not decide which name to use, so she decided to call her Ivy, which, according to Iain, was ‘the name of the heroine of the book she was reading at the time’.8

Ivy was born on 4 November 1911 and met Billy Trimble while they were working as civil servants for the Ministry of Labour in their home city of Londonderry. That was how the Trimbles referred to Northern Ireland’s second city. Others preferred to call it Derry, but Ivy and Billy used the longer title. The name of the city has always been controversial and cuts to the core of Northern Ireland’s identity battle. Unionists have traditionally called it Londonderry, which was the name given to it by the trade guilds from London during the Plantation of Ulster. Nationalists generally regard the ‘London’ prefix as colonial appropriation and therefore refer to the city simply as Derry.

Beyond the name linking it to the UK, there are other reasons why unionists see the ‘Maiden City’ as a special place. The old streets and the world-famous walls close to the River Foyle are all part of the Ulster Protestant psyche. Those of a unionist tradition in a majority nationalist city often felt outnumbered and talked about being ‘under siege’ politically. It was here where the loyalist battle cry ‘No surrender’ was first heard, and it was home to Robert Lundy, who sought to negotiate a surrender. The name Lundy became synonymous with being a traitor to Protestantism. It was a term of abuse often hurled in David Trimble’s direction when he backed the Good Friday Agreement.

The city of Derry is an important part of the Trimble story and helps to explain how he got some of his politics and beliefs. In later life, he often talked about his parents growing up there. Beyond his mother and father, the young Trimble was influenced by Captain William Jack and his wife, Ida, who were his maternal grandparents. Grandfather Jack worked in a timber merchants’ firm and was then employed in the building company Robert Colhoun Ltd, which was run by his wife’s family.

His politics were unionist, and, like many, he signed the Ulster Covenant in 1912, which was part of the campaign to oppose Home Rule. The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 changed everything. The Home Rule Crisis was postponed and thousands of men signed up to fight and help Britain’s war effort. William Jack was one of the many Ulstermen who went off to war, and he initially served with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

He later transferred to the Royal Irish Regiment and eventually ended the war in Egypt. He returned to Derry and settled back into a normal routine, and for the rest of his life lived with Ida. After he died, Ida came to live with the Trimbles in Bangor. She needed some care and support at this stage, as she was elderly and confined to a wheelchair. However, she quickly fitted into family life, and a bedroom was made for her in the dining room.

Even though Ida was physically limited, she was mentally sharp and had a strong influence on young David, as he recalled:

I remember one year when school was off because it was a polling station. I remember coming down a little bit later because I did not have to go to school to find that Grandmother was up and out of bed and in her wheelchair. She was rattling her stick saying, ‘Where is David to take me up to the polling station?’ She grew up in Londonderry, where every vote counted.9

Trimble’s use of the name ‘Londonderry’ illustrates the division over the city’s name perfectly. It was a term he most likely heard from his relatives, like Ida. David’s sister Rosemary says it was clear there was a special bond between David and Ida, and she observed that the ‘two of them really seemed to hit it off’.10

As a child, David enjoyed hearing Granny Ida’s recollections and was particularly fascinated to learn that he may have had ancestors who played a role in the Siege of Derry. Ida was not the only figure who helped to influence his political thinking. A cousin of his mother’s was Jack Colhoun, who was known affectionately as Uncle Jack. He was well known in Derry and was a former politician who ran a construction firm and helped to build the city’s Altnagelvin Hospital. David held him in high esteem and often had political conversations with him at family gatherings. So, when stories emerged about discriminatory practices in the city against Catholics as the civil rights campaign began in the 1960s, David questioned whether the claims were valid:

When we had first of all street disorders associated with a movement calling itself the Civil Rights Association … this was in 1968, I was 24 … it came to me as quite a shock. And what I found most difficult to cope with in that shock is all the things that were being said about discrimination in Londonderry, the city of Londonderry. And it just so happened that my mother came from Londonderry, and a close relative of hers who we refer to as Uncle Jack. Uncle Jack was Mayor of Londonderry. He was active politically and he was Mayor of Londonderry for three or four years in the late ’50s and early ’60s. And these allegations were being made about quite reprehensible behaviour, and I knew Uncle Jack. And I knew him to be a person of personally irreproachable character, and this did not figure.11

For David it was personal. How could unacceptable things be happening in a city where Uncle Jack was a leading figure? It was an example of how David thought and shows how his politics came to be shaped by relatives and friends. Aside from roots in the northwest corner of Ireland, the Trimble family can also be traced back to County Longford, where David’s grandfather, George David Trimble, was born in 1874. Employment was limited, and, instead of farming like many of his neighbours, he joined the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in 1895. He liked the career in uniform and was stationed in a variety of places, including Tyrone, Sligo and Armagh. He married Sarah Jane Sparks from County Armagh in 1903, and the pair had three children. The youngest was Billy, David Trimble’s father. He was born in 1908. There were two other boys, the eldest being Norman, who emigrated to America, and Stanley, who continued the family tradition of policing and joined the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). George arrived in Belfast in 1909 and would gain much experience dealing with the city’s sectarian tensions and rioting.

Policing in Belfast before and after the Great War was tough, and George often found himself at the heart of the trouble. In the 1920s, there was much rioting and violence in the city. At over six foot tall and well built, he was an imposing figure and was clearly well regarded by his superiors. After the partition of Ireland and the creation of Northern Ireland, he also joined the RUC, rising to the rank of Head Constable. He left the force in 1931 and died in 1962, aged 87.

George spent most of his life north of the border, but the family connection to the Irish Republic has not been completely forgotten. In 2023, a bust of David Trimble was unveiled in the Dáil to mark his contribution to Irish history and the peace process. The sculpture by John Sherlock sits near a bust of John Hume, Trimble’s fellow laureate. At the ceremony in Leinster House, Daphne Trimble was reminded of her husband’s links south of the border. She was presented with a piece of stone from the original Trimble homestead, which was situated in the townland of Sheeroe, in County Longford, north of Edgeworthstown.

David’s parents, Billy and Ivy, began their lives together in Derry, and got married at the city’s Great James Street Presbyterian Church on 7 December 1940. Billy was christened William, but he never used that name. Instead, he was universally known as Billy. When David was born, Billy kept up the family tradition and gave his first son the name William David. However, to distinguish him from his father, he was known as David.

An opportunity arose within the civil service, and the Trimbles moved from Derry to Belfast, where Billy was offered a management role at the labour exchange in the city centre. It was a good move, but rather than make their home in Belfast, they decided to settle in Bangor, a pretty seaside resort along the County Down coast. It seemed like a good choice for family life. There was a direct rail line to Belfast, and the town had an excellent mix of shops and good schools. Add to this the access to beaches and the sea, and for the Trimble children it provided the backdrop to an idyllic childhood.

The family’s first home was a terraced house in King Street which was close to the town centre and a short walk to the railway station. They did not remain there long, though, and when David was four years old, the Trimbles moved a short distance to better accommodation in Victoria Road. One of David’s neighbours in Bangor was David Montgomery. He was younger than David and, like many boys who passed the 11-plus examination, would also go to Bangor Grammar School. Montgomery would eventually leave Northern Ireland and carve out a very successful career in the media. As chief executive of Mirror Group Newspapers in the 1990s, he would help Trimble make connections with Labour politicians, including Tony Blair:

The Trimble family were very familiar because they stood out because of their red hair, which was unusual. And they were right at the end of the drive that I lived in. We lived in a terraced house and the Trimbles lived in a semi-detached. In those days, there was a sort of social pecking order. Those people in semi-detached or detached houses would be seen as somewhat grander than the ones in terraced houses. Everybody was very conscious of their status in life.12

The family were now settled into life in Bangor, and schooling was top of the agenda for Billy and Ivy. David initially went to Central Primary School close to the town centre and later transferred to the bigger Ballyholme Primary School, which was nearer the family home. Life at school for the young pupil was mixed. It is clear from his school reports that he struggled in certain subjects, and there were some lessons that he found particularly difficult. His work was not always neat, and some teachers had great difficulty reading his handwriting. At Ballyholme Primary School, Miss Martin recorded that 10-year-old David was very bright and able, but the presentation of his work needed to improve:

David is probably one of the most intelligent in the class yet this report rates him just very average – halfway down. So long as progress is made by written examinations he will remain in this category. Unless he makes a real effort to overcome his indifference and write legibly and intelligently. His work is dirty, carelessly set out and his compositions so full of ridiculous mistakes that often it is not worth marking. Very often he can’t decipher his own figures. Look at his accuracy marks. Five out of ten.13

On the question of whether David might get into grammar school, Miss Martin issued this strong warning: ‘There is not the slightest hope of David getting the scholarship next year unless he eradicates this gross carelessness.’14

David’s parents desperately wanted their son to get a scholarship so he could go to grammar school, which meant that the report from Ballyholme Primary School must have been particularly difficult to accept. Other remarks from Miss Martin showed that David was intellectually capable but was not responsive to the efforts of teachers. In 1955, she wrote: ‘Received little cooperation this year. A pity to make so little use of a good mind.’15

In the months that followed, Trimble’s school work clearly improved, and Miss Martin’s prediction of failure did not come to pass. Much to the relief of his parents, David passed the 11-plus exam and was accepted into Bangor Grammar School. He would be the only Trimble child to pass the test, as both Rosemary and Iain failed.

The Trimbles were naturally delighted that David had secured a place at the local school, which was just a minute’s walk from the family home in Victoria Road. So, in the autumn of 1956, David went through the doors of Bangor Grammar School for the first time. He was a shy, awkward 11-year-old and felt like he did not belong. The early years were difficult, and as with his time at Ballyholme Primary School, his experience at the grammar school would be mixed. Bangor Grammar School was an all-boys school where pupils were streamed, and David was placed in the B stream – a decision based on a test he sat when he arrived at the school. Before he was admitted, he was interviewed by the headmaster, Randall Clarke.

Clarke had only been in charge for a couple years but had already established a reputation as a formidable figure. It soon became clear that he and David were not going to get on.

Clarke had previously taught at Campbell College in Belfast, which had a reputation for being one of Northern Ireland’s leading grammar schools. It was fee-paying, had a boarding department and attracted many pupils from an affluent background.

When he was appointed to Bangor in 1954, the expectation was that Clarke would mimic the ethos and style of his previous school. Ken Hambly, who was in David’s year, says after the new head-master’s arrival the school was jokingly called ‘Little Campbell by the sea’.16

He also recalls how some boys at Bangor Grammar were teased by pupils from other schools for being ‘Bangor snobs’.17 Trevor Low, another contemporary of Trimble’s, says Clarke clearly aspired to turn Bangor Grammar into one of Northern Ireland’s poshest schools: ‘While he was from Northern Ireland himself, he sounded more as if he would really prefer to be the headmaster of Eton or Harrow.’18

Headmaster Clarke had plans for Bangor Grammar and wanted to make the school the first choice for the most able pupils in North Down. He was viewed by the boys and staff as autocratic, and he was not averse to using corporal punishment. He would routinely discipline those who stepped out of line, and he famously expelled several pupils after they kidnapped the Head Boy, roughed him up and abandoned him in the countryside. Clarke wanted his pupils to conduct themselves in a certain way, as Low recalls:

There was a school rule whereby you had to wear your school cap and your school uniform downtown all the time, and that included Saturdays and Sundays. So, you didn’t come home from school and change into casual wear and then go downtown to go shopping or something. You had to wear your school uniform all the time.19

Ken Hambly says it would be wrong to portray Bangor Grammar as elitist, and, in his experience, he thought it was ‘a perfectly ordinary regional school’.20 What is clear is that Clarke’s tenure helped to define the ethos of the school and in turn that influenced how pupils behaved and learned. Terry Neill, another Bangor Grammar School old boy, who was at school at the same time as David, recalls the influence that Clarke had on the pupils:

He had a great respect for academic excellence and prowess and was encouraging. He was a bit humourless. He was stern, a sort of a disciplinarian.21

Trimble clearly experienced Clarke’s stern side, and the headmaster regarded him as academically challenged. The personality clash between Trimble and Clarke may partly explain why he did not look back at his days in Bangor Grammar with much fondness. Marion Smith, who served as a local UUP councillor in Bangor, and was mayor of North Down, remembers being asked by Trimble, when he was an MP, to deputise for him and attend an event at Bangor Grammar School. Trimble had been invited as a guest speaker but did not attend.

Smith got the distinct impression it was simply because Trimble’s schooldays were not happy ones. Much of his unhappiness may be linked to his poor relationship with Clarke who, as well as being the headmaster, taught Trimble history:

There were only seven of us in that class and I disliked Randall intensely as a person because he was fussy and was reluctant to let me in. For the first months of that course, he kept telling me how lucky I was to be in it.22

David made a slow start to life at Bangor Grammar. In his first few years his results were average, and he made little academic progress. An early report showed that in a class of 47 boys he was placed 32nd. For David’s parents it must have seemed like history was repeating itself. Their son’s spelling was regarded as disappointing and, as with his time at primary school, the staff found his work ‘too often untidy’. The concluding remarks suggested that he had potential but needed to work harder. The teacher’s analysis read: ‘Quite a good report. He has definite capabilities which too often he does not use to the full.’23

A theme was beginning to emerge about David’s approach to school-work. He was clearly bright and a good thinker, but his written work was messy and careless, which resulted in him not reaching his academic potential. What is also clear from his early days at the grammar school is that he did not take things seriously. Iain remembers one incident when David’s tomfoolery had serious consequences:

He was misbehaving somewhat in class and decided for whatever reason he was going to run down the length of the classroom on top of the desks. So, he is leaping from desk to desk and he hit his head on one of the beams and knocked himself out.24

It is not known if the young Trimble was disciplined for his desk walking, nor is there any suggestion that the bang on the head did any major damage. There are other reports of David allegedly misbehaving at the school. A fellow pupil claims the future politician was part of a group of boys who bullied him during his time at Bangor Grammar. He claims David was ‘not vicious compared to other boys in the gang’ but says he was humiliated by him.25

The victim decided to take revenge and, according to the journalist and biographer Henry McDonald, he went to a Bangor gunsmith and purchased an old rifle and then made his own ammunition. His intention was to go to school and frighten or shoot David. According to McDonald, the plan was thwarted by a teacher, who handed the would-be gunman over to the RUC.

Away from the classroom there was much to occupy the mind of the young teenager. David was interested in the Royal Air Force (RAF), and at one stage it was thought he might join. His brother Iain did join, aged 16, and had a very successful career in the force, but David’s prospects always seemed limited, as he had poor eyesight. Despite this, he enrolled with the RAF 825 Squadron of the Air Training Corps (ATC) in Bangor and threw himself into the group’s activities.

He quickly became enthusiastic about the opportunities the ATC offered, and his spare time was spent on training nights, exercises and trips across Northern Ireland and in Great Britain.

The summer camps presented lots of fun for David and his friends. They learned about handling weapons, had glider training and were taught map-reading skills. At night in the barracks, they would play cards, or they would sneak off to the local pub in the hope that the bar staff would not question their ages. It was a formative time for David and helped him mature and learn valuable life lessons. It was there he met Leslie Cree, who would become a lifelong friend and would have a strong influence on Trimble’s decision-making.

The two had similar interests and would both end up joining the Orange Order and the UUP. Cree would later serve as a Member of the Legislative Assembly at Stormont when Trimble was party leader. He remembers that, when he met David for the first time as a schoolboy, he thought he was ‘shy, timid and a bit of a boffin’.26

He also recalls that David enjoyed learning to shoot:

He was a bit short-sighted, but you know at a 25-yard range with a .22 rifle it was not a problem. He liked that. That was a big interest we had in common. I was mad keen on shooting too.27

Iain was also an ATC member and would often accompany him on trips and at training camps. He remembers one occasion when brotherly love was forgotten, and David failed to look out for him:

We had gone to RAF Cosford, which is an RAF training camp in the Midlands, on the ATC summer camp. And during the night there was a fire practice, so everybody got up and went outside to line up, except me who was fast asleep. And my brother didn’t even come back to wake me up.28

Home life for David was pretty settled. He had school during the day and the ATC at night and at weekends. Going to church was part of the family routine and they worshipped at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Bangor, as Iain recalls:

We went to church every Sunday. We sat in the same pew and that was that. We went to Sunday School and there was Bible Class later and church in the evenings and things like that. So, it was typically a standard Irish Presbyterian upbringing.29

David clearly enjoyed church life, and as he got older, he began to get more involved in helping at church services. On Sundays, as Iain recalls, he ‘took over controlling the volume of the loudspeakers which were at the back of the church and up in the gallery’.30

David’s faith was a constant in his life, and when he got married and had children, his own family followed a similar routine to the traditional Sunday he experienced in his youth. As a child in Bangor, David and his siblings enjoyed modest family holidays, often in Scotland and across Ireland. They went cycling and travelled on a budget, frequently staying in youth hostels.

It was a happy home, although David’s relationship with his parents appears at times to have been strained. Rosemary says it was their mother who ran the household: ‘Mummy could have been strict. Father was easier going.’31

Ivy Trimble was clearly class-conscious and wanted her children to socialise with other children from similar backgrounds. According to David, she viewed herself as ‘very middle class’.32

Billy Trimble enjoyed a drink and was a smoker. Iain remembers how his father would often come home from work, eat his evening meal, listen to the news and then go off into Bangor for a few drinks. He says during his teenage years David rarely spent time with his father and ‘would stay out of his way in his bedroom with a book’.33

David was very happy in his own company as a child:

I have always been fairly independent. At an early age my mother complained that I’d always do things in my own way.34

While he was at school, he began to take an interest in pop music, and particularly Elvis Presley. The American singer was a worldwide sensation. His good looks, charm and unique voice brought him global fame. David was fascinated by him and regularly bought his records, and even went to the cinema in Bangor and Belfast to watch his films. It was the start of a lifelong fascination. Rosemary remembers her brother’s obsession:

He had quite a collection of Elvis Presley records. He had most of the hit records. I can remember him going upstairs to study and go to his room. Then a few minutes later the music came down as well. He was always playing those records, over and over again. Everyone was well used to hearing Elvis. Mum and Dad just put up with it and shrugged their shoulders.35

A job as a barman in the Queen’s Court Hotel in Bangor helped the young music fan subsidise his record buying. If he wasn’t saving up for Elvis records, he was frequenting bookshops and purchasing history books. By his mid-teens, his results at Bangor Grammar began to improve and his reports started to reflect that he was maturing and showing a greater commitment to his schoolwork.

By the summer term of 1959, it was clear he was trying hard, and several teachers praised his efforts, although the old Trimble academic trait of ‘careless errors’ still popped up in the comments section.

When the Easter term of 1960 arrived, David’s schoolwork had improved even further. He was first in the class in geography, scored well in history and performed better than expected in arithmetic, algebra and geometry, but his German teacher, unsurprisingly, noted that his work was ‘far too careless and untidy’.36 Aside from the need to smarten up his presentation of essays and coursework, it is clear he was now becoming a more confident student and beginning to develop opinions and ideas.

David did well in his exams and successfully entered sixth form with much confidence. His end-of-term reports got better, his work was tidier and he was starting to get glowing references from his teachers. He studied Geography, Ancient History and Modern History at A level and was at last living up to his academic potential.

He was also interested in learning to drive, and he promptly went out and with his earnings bought himself a Rover car. However, on the first day he took his new purchase out on the road it all went horribly wrong, as Iain recalls:

He bought a car when he was still relatively young, and his first lesson was when we were living in Clifton Road. He came along Clifton Road towards the crossroads at the top of High Street and he turned left. He forgot to straighten out and he ran straight into the lamppost.37

Ivy was furious when she heard about the accident and gave her son a telling-off for his carelessness. In contrast, David’s siblings and friends in the ATC found the episode highly amusing and routinely teased him about his inability to drive. The accident had quite the effect on him. It ended his driving career for years, and he did not proceed with any more lessons.

The crash had put him off driving, and for the next two decades he relied on public transport and lifts from other people. He only learned to drive later when he was married with children.

David had also started to become interested in the Orange Order, and while he was away at ATC camps, he began to have conversations with Leslie Cree, who was already a member. There were a number of active lodges in Bangor, and Cree was a member of Bangor Abbey lodge, also known as Loyal Orange Lodge 726. Cree remembers chatting to David one night about joining:

I talked about it and the history to do with it, how it had been involved in politics and world affairs … And he was interested. He asked me lots of questions about how it works, and I explained to him the structure and all that [this was a private lodge]. He also knew that another six or eight of the boys [in the ATC] were members of it too.38

Trimble’s decision to join the Orange Order is worth examining.

He was aware of its exclusive membership criteria and knew that it excluded Catholics. This obviously meant his Catholic friends at Bangor Grammar and the ATC could not join. He would have also been mindful that it was viewed by some as a bigoted and extreme organisation. Yet, that did not seem to be a barrier to him. On the face it, for a middle-class grammar schoolboy, joining the Orange Order might seem like an odd thing to do. There was no expectation within the Trimble household that he would become involved, although he did have family connections to the Order.

He later told the BBC that one of his grandfathers was in the Order, and Thomas Trimble, his grand-uncle, who lived in County Longford, was Worshipful Master of the Kilglass Loyal Orange Lodge.

Interestingly, his parents Billy and Ivy were not members, although his brother Iain did join. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Orange Order was an influential body in Northern Ireland and was linked to the Unionist Party. Most of its MPs were members and party meetings were often held in Orange halls. The Order was seen by many as an integral part of the state of Northern Ireland, and Orange culture often set the narrative for unionist rule at Stormont. David would have known about the Order’s influence as a student of history and current affairs. However, his desire to join may have been based on social reasons rather than careerist motives.

Once a member, he became active in the lodge, attending meetings, often with Leslie Cree at his side, and taking part in parades, including the traditional 12 July demonstration that commemorates King William’s victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. This was another extracurricular activity for David, which meant outside school he was very busy with his bar job, church, the ATC and now his membership of Loyal Orange Lodge 726.

However, as he approached his A levels, he knew studying had to take priority.

2

FIRST AMONG EQUALS

‘William David Trimble, 39 Clifton Road, Bangor, gained the Bachelor of Law with First Class Honours. The only Queen’s student to do so for the past three years.’ County Down Spectator, 5 July 1968

By the start of summer 1963, David Trimble was on track to do well in his final exams at Bangor Grammar. His teachers, some of whom had been very critical, now had high hopes for him. His ancient history teacher wrote that he was ‘a keen pupil and has worked well throughout the year’. His House Master was also complimentary and commented that ‘he has shown remarkable improvement and a maturity of thought’.1

There was still concern amongst the teaching staff as Trimble prepared to leave. In his final report, one teacher wrote of the future Nobel laureate, ‘this boy has a lively mind which sometimes leads him into irrelevance which can be disastrous in examination answers’.2

However, the expectation was that Trimble was on course to perform well. Even his severest critic, the stern headmaster Randall Clarke, was upbeat. He said that Trimble had achieved ‘a most creditable report. He has improved very considerably this year in every respect.’3

Clarke’s assessment was light years away from his earlier comments, when he suggested that Trimble was lucky just to be in his history class. As Trimble’s time at Bangor Grammar ended, it was clear he had defied expectations and was beginning to shine academically. He was also developing quite an interest in politics.

He was well read, probably better than most of his peers, and he was well informed on world events. Trevor Low remembers their final days together at Bangor Grammar School:

In our last year of school, we had a current affairs class and David and I actually sat right next to each other. And back in those days the main subject of conversation was probably communism with all the trouble between Cuba and Nikita Khrushchev as the Russian leader. JFK was the American leader, and that last year of school was probably one of the main topics of conversation. And David was always very interested in the political situation and the world situation. He always struck me as being a very serious-minded boy. Yes, he had a sense of humour, but he was not one of the lads.4

Even though Bangor Grammar School had quite a sporting pedigree, it did little to excite Trimble the teenager. He had no interest in playing cricket or rugby and preferred the library to the games pitch. He continued to devour books and, with his growing knowledge of current affairs, was able to hold his own in debates and discussions. Even though he was naturally shy, there were times when he felt confident to challenge the opinions of strangers. Leslie Cree remembers being at an ATC camp in England when he and Trimble wandered into a nearby town centre:

We were walking along, and this guy was on a street corner pontificating about something and there was a crowd around him. And we stopped to listen. And before you could say, ‘Jack Robinson’, David was saying, ‘No, that is not correct’. And the rest of us just looked at him.5

Near the end of Trimble’s time at school, he started to have conversations with his parents about what he should do next. His father was keen on his son taking a job rather than going to university, and he encouraged David to think about a career in banking or the civil service.

When his exam results came in, they were excellent. He performed well in modern and ancient history, and geography. Trimble loved history and clearly had an aptitude for it. His desire was to study it at Queen’s University. However, he had been told by a teacher at Bangor Grammar that to be a history student with honours at Queen’s he needed a Latin qualification. Trimble didn’t have one, and because of the guidance he was given he did not apply. It transpired that the information from the careers master was incorrect – and Trimble could have applied for his dream course.

By the end of summer of 1963, it was too late to reapply, so he had to think of an alternative option.

Not surprisingly, Billy Trimble continued to talk to his son about the possibility of other careers. The idea of joining a local bank was mooted, as was the prospect of applying to the Northern Ireland Civil Service, which would have meant following in his father’s footsteps. Billy was keen on this option and firmly believed that a role with a government ministry would provide a decent salary and job security for his son. As luck would have it, an advert seeking staff for the Northern Ireland Civil Service appeared, and within days the 18-year-old was a candidate. Trimble’s application was successful, and in September 1963 he began life as a civil servant and found himself working as a clerk in the Land Registry offices in Belfast, where title deeds were stored. His job involved recording the details of property transactions and in particular changes of ownership.

It was dull work and involved much laborious form-filling, which Trimble disliked. However, the ambitious Trimble had a cunning plan, one that he hoped would take him away from the boredom. His employer had recently introduced a scheme to offer staff members legal training, as the civil service was experiencing a skills shortage. Trimble recalled what happened next:

The civil service was having difficulty retaining people in two legal branches, Land Registry and the Estate Duty Office. So, they were going to send civil servants to take a law degree, guarantee them promotion up to a certain level if they did so. So, after a year in the civil service, I started doing this course.6

In 1964, the Northern Ireland Civil Service awarded two places to Land Registry staff to allow them to study law degrees on a part-time basis. They would keep their jobs and combine studying with working, and once they were legally qualified they would hopefully advance up the career ladder. Trimble was delighted to be selected. He had finally arrived at Queen’s University – albeit via a circuitous route. He had become the first member of his family to go to university. The civil service scheme was very competitive, and he was awarded a place alongside Herb Wallace, who, like Trimble, had not long joined the department. The two men became friends and would later become colleagues at Queen’s University. Wallace remembers being introduced to Trimble in the Land Registry office and first noticed ‘his really red hair’.7

He would get to know Trimble very well:

I think he was an odd man in many ways, but he was very principled. You know some people are like that and David was the kind of person who could never tell a lie to anybody. He would not think that was appropriate at all. And I think that was woven throughout his career. Sometimes, I think he hurt people because he just told them the truth.8

Wallace was a little like Trimble. He was shy, ambitious and keen to make a success of the opportunity at Queen’s. They went to classes together, shared lecture notes and began to spend a lot of time in each other’s company. Wallace was impressed with Trimble’s grasp of current affairs and the two would often chat about what was in the news:

We would both have been supporters of the Ulster Unionist Party, although I think David was slightly more interested in politics than I was. We wouldn’t have disagreed with anything politically and we worked very closely together in our studies. We helped each other with studies and so on. There was actually no rivalry between us, certainly at that stage. I regarded him as a fairly close friend.9

The two men were part of the second phase of civil servants who went to Queen’s as part of the scheme. Sam Beattie, who was also employed in Land Registry, had gone the year before:

We were trained in the civil service, and we tended to treat it with respect. If we had a lecture from ten to eleven, we were back in the office at half eleven. If you had a lecture in the afternoon, you attended it and went back into the office. So, you were up and down the University Road a lot. Trimble and Wallace followed us in and realised very quickly that there was room for manoeuvre here. So, they didn’t come back into the office as sharply as they might have done.10

Staff from Land Registry on the degree scheme were allowed to leave the office to attend classes at Queen’s but were expected to return to work promptly after the end of a lecture or tutorial. However, Trimble and Wallace got a little crafty with the way they combined work with their studies. They quickly realised that they could choose the timings of their tutorial groups, and if they planned things carefully, they could stay away from work for a bit longer and maximise their time at Queen’s. Both men coordinated their timetables, so questions were never raised by their superiors.

Trimble and Wallace threw themselves into the course at Queen’s and impressed the teaching staff with their ability and coursework. As they approached their final year, they were invited to a meeting by two senior lecturers, William Twining and Lee Sheridan, to discuss their future. The Queen’s professors rated the two students and had a suggestion for them. Wallace remembers what happened:

David and I were invited together to a meeting with these two guys, and they said, ‘We think you are both candidates for a first-class honours degree. They said they were ‘not sure you can achieve it if you are only part-time students, spending a lot of time in the Land Registry. So, would you consider becoming full-time students for your final year?’ At that stage, I had a wife, a mortgage and a child that was due to be born within weeks. I decided I just could not afford to do that. David, on the other hand, at that stage, did not have any encumbrances like that. He decided to go full-time for his final year.11

Trimble jumped at the leave of absence from Land Registry for the concluding year of his degree and became a full-time student. By that time, the Trimble family were living in a bigger house in Clifton Road in Bangor. It meant the three children could have a room each and Trimble stayed at home and travelled to Belfast every day. Iain Trimble remembers that he saw little of his brother. He recalls that most days he ‘came home, had his meal and disappeared upstairs or occasionally he would disappear with some of his friends’.12

Home life was not without its difficulties. Billy Trimble was not well. He had been diagnosed with lung cancer and initially doctors thought they could operate and prolong his life.

However, it became clear that his condition was advanced, and surgery was not an option. He only had a short time to live, and as his son’s final year at Queen’s progressed, he became gravely ill.

Trimble threw himself into his studies in the summer of 1968, and was awarded first-class honours. It was an outstanding achievement, as the awarding of such honours was rare. He was also the recipient of the McKane Medal for Jurisprudence. Trimble’s decision to step away from his civil service role had paid off, and he had delivered what his professors said he was capable of. Wallace says Trimble’s success was impressive:

A first-class degree never went to more than one person from the year, and in some years, nobody got a first … we graduated in 1968, and I know in 1967 there were no first-class honours afforded. So, it was a big thing, and it was a big achievement for him.13

Sam Beattie says Trimble’s triumph was richly deserved and he was by far the best student in his year, as he was ‘well read, well informed and able to argue well’. News of the success reached the offices of Trimble’s local paper in Bangor, and on 5 July 1968 the County Down Spectator ran a story on its front page.

At this time of year, it gives us pleasure, if also a headache, trying to follow the fortunes of the many local students at Queen’s to record academic successes as they become known. In the Faculty of Law, William David Trimble, 39 Clifton Road, Bangor, gained the Bachelor of Law with First Class Honours. The only Queen’s student to do so for the past three years. David achieved this while studying part-time and working in the civil service.14

The article was accompanied by a photograph of the successful graduate. Trimble was featured looking smart, with short hair and his trademark thick glasses. He did not recall reading the article at the time, but in a BBC interview he was presented with a copy of the article and read it out on air. He told the interviewer, John Wilson, that he recalled the summer of 1968 for a variety of reasons:

I was certainly proud of the result. I don’t remember seeing that [the newspaper article]. The other thing I have to say was that my father was fatally ill at the time and died the night before graduation.15

Billy Trimble’s final days were difficult. He had fallen and broken his leg at the family home in Clifton Road and had been admitted to hospital. The lung cancer at this stage was well advanced, and in the days after his fall he declined rapidly. Iain, who was serving with the RAF in Cyprus, was given compassionate leave to come home. He arrived back in Bangor for his father’s last days and was also able to attend David’s graduation. Understandably, Billy’s death rocked the family. As David graduated, on what should have been a joyous occasion, he was having to deal with the realisation of his father’s death. It was a poignant and bittersweet moment.

By being admitted to university and then being awarded a degree he had done something that no other member of his family had ever experienced. He had defied the odds and proved teachers at Bangor Grammar School wrong. Unlike during his early days at school, he had found something that sparked his imagination, and he had triumphed in style. For Trimble, 1968 was life-changing. On the strength of his success at Queen’s, he was offered a teaching post at the university, which was quite rare.

He became an assistant lecturer in the Law Faculty with the responsibility to teach land law and equity. It meant his days in the civil service were over. The new job was only part of a fresh beginning.

In September 1968, a few weeks shy of his 24th birthday, Trimble married Heather McCombe at Donaghadee Parish Church. The pair had begun a relationship when they worked together at the Land Registry offices. It was Trimble’s first serious love affair, and their union and subsequent marriage surprised many of his friends. Herb Wallace remembers that the first time he saw the pair together was at the office Christmas party in 1967, and he was taken aback to discover they had started dating. A few of Trimble’s friends and family members thought they were an unusual match, although they kept their thoughts private.

Trimble and his wife had contrasting personalities. He was introverted and awkward, whereas Heather was an extrovert, outgoing and popular. Despite their differences, the couple were in love, enjoyed each other’s company and began planning a life together. After their wedding in County Down, they honeymooned in County Wicklow and then set up home together.

Life for David Trimble was changing at a dramatic pace. He had graduated, lost his father, got a new job and become a married man, all in the space of a few months. By the autumn of 1968, he was getting used to teaching undergraduates at Queen’s – some of whom were just a few years younger than he was.

At the same time, Northern Ireland was now making world headlines. A civil rights campaign highlighting discrimination against Catholics was gaining momentum and attracting media interest.