Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

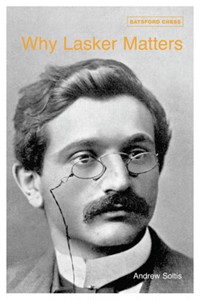

Strategies and examples for beating a superior opponent in chess. Chess history is littered with David vs Goliath chess struggles where the weaker player has prevailed. Chess masters, even international grandmasters, can be defeated by young, improving players who use the right techniques and proper attitude. In David vs Goliath Chess, renowned chess writer Andrew Soltis takes you through 50 annotated games that show how weaker players have scored stunning upsets by overcoming a superior opponent's greater knowledge and experience. He gives tips on everything from the best psychological mindset to take on a strong player, to studying your opponents past games, identifying weaknesses and identifying chess strategies he or she won't expect. A great chess improver book that will benefit any regular chess player, including club players, giving the reader confidence to take on anyone at chess.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 303

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Chapter One: It’s Good To Be A David

Chapter Two: When Titans Fall

Chapter Three: All Hail the Unknowns

Chapter Four: One, But A Lion

Chapter Five: First Round Fearless

Chapter Six: Show Time

Index of Players

Index of Openings

Chapter One:

It’s Good To Be A David

Masters are our heroes. Grandmasters are our super-heroes. We honor them and study their games. We respect their strengths, their superior skills.

How can a much lower-rated player, a David, manage to last long against such a Goliath, we wonder?

What we fail to appreciate is that stronger players also have vulnerabilities. They are not vulnerable in spite of their strengths. They are vulnerable because of their strengths:

Goliaths fear draws

A player who outrates his opponent by one class (200 points) should score better than 75 percent. That is, in a four-game match, he would be expected to get at least three points. If the rating difference is a bit more, he should get three wins and only allow one draw, according to the Elo system.

He would be satisfied with that, wouldn’t he? No, not at all.

Higher-rateds feel that wins are the natural result when they face much weaker players. Wins should happen. Draws shouldn’t. Draws are disappointing.

What this means for a prospective David is that a Goliath won’t be content to draw. If the game goes on long enough, he may try to get more out of the position than he deserves.

Or to put it more exactly, more than the position deserves.

Play went 1 ... ♕h3+ 2 ♔g1 ♕h5.

White signaled his willingness to shake hands, with 3 ♔g2.

Black saw nothing better than 3 ... ♕h3+ and White replied 4 ♔g1.

Black was a strong grandmaster. He had once been the world’s third-ranked player and a potential world championship challenger. But in this position he had no reason to refuse the tacit offer of a draw that White has made.

Objectively, the position is even. White is the one who is most likely to open the center favorably with e4-e5.

Black chose 4 ... ♔g7? and quickly went downhill, 5 ♗f1 ♕c8 6 ♗g2 dxe4 7 fxe4 ♘xa6 8 e5!.

Now 8 ... fxe5 9 ♘xa6 ♕xa6 10 ♖xe5 ♖xe5 11 dxe5 would threaten ♕xg5 and ♕d7+ (11 ... ♕b6+ 12 ♔h1 ♕d8 13 ♕xd8 ♖xd8 14 ♗xc6 is a big endgame edge for White). Or 11...♘f7 12 e6!.

Instead, the game went 8 ... ♘xc5?? 9 exf6+ ♔xf6 10 ♖xe7 ♖xe7 11 ♖xe7. Since 11 ... ♔xe7 12 ♕xg5+ is hopeless, Black played 11 ... ♕f5 and resigned after 12 ♖e5 ♕b1+ 13 ♖e1.

Why did Black reject a draw? He would have readily accepted one against a player who was closer to him in rating. His position didn’t tell him to play for a win. His rating did.

You’ll find similar examples in this book in which a much higher-rated player loses because of an irrational fear of perpetual check or repetition of the position. But rejecting a tacit – or overt – draw offer is not the only way that a fear of drawing endangers stronger players:

A Goliath as Black may avoid playing the opening he knows best. Why? Because that opening is designed to equalize against other Goliaths.

For example, he may normally meet 1 e4 with the Petroff Defense or the Berlin Defense of the Ruy Lopez when playing an equal. But those are not high-percentage weapons. Rather, they are I’m-happy-to-draw-with-you-today, Fellow-Goliath openings.

So, he may choose to play a Sicilian Defense that he knows less about, just because it is sharper. There are several examples of Sicilian upsets in this book. Similarly, a Goliath may answer 1 d4 with 1 ... d5 against another Goliath. But against a David he will risk a King’s Indian or Benoni Defense – and live with the consequences.

In addition, a Goliath may opt for a double-edged middlegame when he would normally head into a slightly favorable endgame. He is abandoning his usual style of play – what former world champion Vladimir Kramnik called “normal chess.”

“I should play more normal chess,” Kramnik said in a 2015 open tournament where he faced weaker opponents. “But somehow I want to win too much every game.”

There are other vulnerabilities of higher-rated players:

Goliaths are overconfident

Their success fosters complacency. Complacency breeds carelessness. Carelessness costs.

Take the case of John William Schulten and his battles with Paul Morphy. Schulten was a 19th century American wine merchant who often visited Europe on business. He loved to drop in at chess hangouts and challenge the best players.

His enthusiasm far outran his ability. As a result he became one of the greatest losers in chess history.

Virtually all of his surviving games are defeats – and there are likely to be hundreds of other losses that were not recorded. The list of his vanquishers reads like a Who’s Who of Romantic-era chess – Adolf Anderssen, Johannes Zukertort, Pierre Saint Amant, Ignatz von Kolisch, Lionel Kieseritzky, Bernhard Horwitz, Gustav Neumann and Morphy.

Schulten came to New York in 1857 solely to play Morphy, according to Morphy biographer David Lawson. They contested 24 games over a short period. Morphy won 23. Here’s the 24th:

Schulten – Morphy

New York 1857

Falkbeer Countergambit C31

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 ♘c3!?

This was considered a reasonable alternative to 4 d3 at the time.

4 ... ♘f6 5 ♗c4 c6?! 6 d3?! ♗b4

The drawback to 4 ♘c3 is this pin, which can occur in a number of move orders.

7 dxe4 ♘xe4 8 ♗d2 ♗xc3 9 ♗xc3

9 ... 0-0?

Schulten refused to accept material odds so Morphy was playing blindfold. That is, he made his moves without looking at the board. But his moves indicate he chose them without caring about the board. Against a stronger player he would have won with 9 ... ♕h4+ 10 g3 ♘xg3.

10 ♕h5 ♖e8 11 0-0-0 ♘xc3 12 bxc3 ♕a5 13 ♔b2 g6 14 ♕h6 ♗g4? 15 ♘f3 ♗xf3 16 gxf3 b5? 17 f5!

A small miracle has occurred. Now 17 ... ♘d7 18 ♗d3 b4 allows 19 fxg6 fxg6 20 ♗xg6 and wins.

17 ... bxc4?? 18 f6 Black resigned.

“Undoubtedly the monotony induced by so many wins accounts for his lapse in a single game,” Lawson wrote.

This is far from unique. Some of the worst defeats suffered by the greatest players came about because they just weren’t concentrating. The following game was played by a world champion during a 33-board simultaneous exhibition.

Capablanca – Kevitz

Brooklyn 1924

Orangutan Opening A00

1 b4 d5 2 ♗b2 ♗f5 3 e3 e6 4 f4 ♘f6 5 ♘f3? ♗xb4

Black couldn’t take the pawn earlier (4 ... ♗xb4? 5 ♗xg7). Capa apparently just forgot that it was hanging.

6 ♘c3 ♘bd7 7 ♘e2 ♘g4!

The threat of 8 ... ♘xe3 prompts another concession. Computers recommend 8 ♗c3 or even 8 ♘c3. Those moves are beneath the dignity of a world champion.

8 c3? ♗e7 9 h3 ♘c5!

With a threat of ... ♘d3 mate. Black later became a strong master but at the time he was just a promising amateur.

10 ♘g3 ♗h4! 11 ♘xh4 ♕xh4 12 ♕f3

Hoping for 12 ... ♘e4? 13 hxg4 ♕xg3+ 14 ♕xg3 ♘xg3 15 ♖h3! and White has turned the game around.

12 ... ♘xe3!

But now 13 dxe3 or 13 ♕xe3 allow 13 ... ♘e4 and Black will be two pawns up.

13 ♕f2? ♘xf1 White resigned.

In view of 14 ... ♘d3(+). Also winning was 13 ... ♘c2+.

Another Achilles heel of stronger players is:

Goliaths want to win effortlessly

Davids usually beat themselves. They make blunders when paired way up. Goliaths can rely on routine moves and wait for the double-question-mark moves.

“Well, I haven’t seen this lemon before,” GM Maxim Dlugy wrote about a dubious sixth move that a much lower-rated opponent played against him. “I guess I should just let him get in his weakening moves.”

Dlugy responded with hum-drum replies. Soon his position was only slightly favorable. He got careless, blundered and lost.

A Goliath knows he can beat most Davids with very little thought. He can choose most of his moves based on intuition. He plays the first move that occurs to him.

Thanks to their superior intuition, this usually works. This is why a master can give a 20-board simultaneous exhibition, and score 19-1 or even 20-0 in less than three hours.

But when a Goliath depends on intuition he isn’t calculating as he would against an equal. Many upsets come about because Goliaths didn’t see a tactical resource for their opponent.

White was a nine-year-old player rated 1681. Black was a master, rated nearly 600 points above her. The rating system says his winning chances – compared with losing chances – were about 96 percent.

And he could have won with 1 ... ♖d8!, cutting off the knight’s escape. There is no defense to 2 ... ♖d7 and 3 ... ♕f7 followed by capturing the knight.

Instead, he played 1 ... ♖c8?? and was lost after 2 ♘d5! ♕e6 3 ♖xc8 ♖xc8 4 ♖xc8+ because 4 ... ♕xc8 5 ♘e7+ loses the queen. White, a future grandmaster, went on win. But at the time this was played, she was the youngest player to defeat a US master.

Some Goliaths want to win quickly

They don’t want to just beat much weaker opponents. They want to crush them.

So they may try a risky opening. This often results in a win in fewer than 25 moves against an opponent who is seeing this line for the first time.

Paul Keres won many games like that. But this adventurism also carried risks:

Keres – Menke

Correspondence 1933

King’s Gambit Accepted, Mason Gambit C33

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘c3 ♕h4+ 4 ♔e2 d5 5 ♘xd5 ♗g4+ 6 ♘f3 ♘c6 7 ♘xc7+ ♔d8 8 ♘xa8 ♘e5 9 h3

Here or on the next move White should play ♕e1.

9 ... ♗h5 10 ♖g1??

10 ... ♕g3! 11 ♕e1 ♘xf3 12 gxf3? ♕xf3 mate.

Anti-Goliath strategies

There are occasions when a very strong player beats himself. Here is how a former world champion self-destructed against an opponent he outrated by more than 300 points.

Lieb – Spassky

Munich 1979

Vienna Game C26

1 e4 e5 2 ♘c3 ♘f6 3 ♗c4 ♗c5 4 d3 ♘c6 5 f4 d6 6 ♘a4!?

The normal move is 6 ♘f3. White’s move scores well in databases and was a favorite idea of Boris Spassky’s in similar positions.

6 ... ♗xg1 7♖xg1 ♘g4 8 g3 exf4 9 ♗xf4

Spassky may have been tempted by 9 ... ♘ge5 because it threatens 10 ... ♗g4, followed by a knight fork, or 10 ... ♘xc4, eliminating the nice bishop and damaging White’s pawns. But 9 ... ♘xh2 also threatens 10 ... ♗g4 and it wins a pawn.

Unfortunately, Spassky overlooked 10 ♕h5!, which threatens mate on f7. He struggled for another 13 moves after 10 ... ♕f6 11 ♕xh2 before resigning.

But in the vast majority of cases, a David has to make an upset possible.

There are four guidelines that serve as good advice.

They are:

Play actively

Too many would-be Davids begin a game defensively. They are already thinking about losing. When they realize their position is inferior, they hunker down. They look for defensive moves, passive moves.

Goliaths thrive on exploiting that. “A strong player’s sense of weakness is kind of like a dog’s,” GM Larry Christiansen said before giving a simultaneous exhibition in 2016. “If you play like ‘Mr. Passive,’ we welcome that.”

Davids should be looking for aggressive moves. Nothing is more likely to disorient a Goliath than threats. By the time he has built up a big edge, the idea of losing has been banished from his mind. He may be vulnerable to even a desperation tactic.

Beukema – van Herck

Belgian Open Championship 2013

Caro-Kann Defense, Advance Variation B12

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 c5 4 c3?! ♘c6 5 ♗b5 ♕b6 6 ♗xc6+ bxc6!

Black, a 2100-player, tricked his lower-rated opponent with a somewhat rare third move (best met by 4 dxc5!).

His last move is the kind a superior player finds with his intuition. He created a second c-pawn to attack the center (... cxd4 can be followed by ... c5!). He also opened the best diagonal on the board for his c8-bishop.

7 ♘e2 e6 8 0-0 ♗a6 9 ♖e1 h5 10 ♘f4 g6 11 ♕c2 ♘h6 12 b3 ♘f5 13 ♗e3 ♖c8!

Black could have assured himself of an advantage with ... cxd4 at any point, with or without ... ♘xe3. He is playing for more, perhaps to win in fewer than 30 moves.

14 ♕d2 cxd4 15 cxd4 ♗b4! 16 ♘c3 ♘xd4! 17 ♗xd4 c5

It’s been an embarrassment of riches for Black. He could have secured a solid edge with 16 ... ♘xe3 and 17 ... c5. Also good was the immediate 16 ... c5 because 17 dxc5 ♕a5 would win material (18 ♖ac1 d4! 19 ♗xd4 ♖d8).

But his choice should also win, e.g. 18 ♗e3 d4 (19 ♖ac1 ♗xc3 20 ♖xc3 dxc3 21 ♕xc3 ♕b4 22 ♕c1 c4).

Instead of rolling over and dying that way, White found:

18 ♘fxd5! exd5 19 e6!

There was little to lose. White gets to make threats (♗xh8 and exf7+).

Black might be tempted by 19 ... ♖h7 but 20 ♕g5! is strong (20 ... cxd4 21 ♘xd5! or 20 ... ♗xc3 21 exf7+ ♔xf7 22 ♖e7+ and wins).

19 ... 0-0??

But 19 ... cxd4! would have won quickly. Black may have assumed he could capture on the next move.

20 ♕h6! cxd4 21 ♘xd5! Resigns

There was no defense: 21 ... ♕d8 stops mate but allows 22 ♖e5 and 23 exf7+.

Of course, Black should have won, even after 18 ♘fxd5. White’s refusal to go quietly made the upset possible.

Encourage chaos

John Grefe, who co-won a US Championship, was vulnerable to Davids. In open tournaments, he was occasionally beaten by players rated more than 500 points below him. “I can’t play against them,” he complained. “They don’t know what they’re doing.”

What they were doing was creating the kind of double-edged position, even at positional cost, that Grefe hated to play. They sought chaotic middlegames and double-edged endgames.

One of Simon Webb’s mantras in his classic book Chess for Tigers was that weaker players should try to “randomize.” As he put it,

“The basic principle is to head for a complicated or unclear position such that neither of you has much idea of what to do, and hope that he makes a serious mistake before you do.”

This sounds like terrible advice: After all, won’t a Goliath be able to calculate a chaotic position, a random position much better than you?

Well, if the position is one given to calculation, the answer is yes. But Goliaths aren’t computers. There are severe limits to human evaluation.

Just as bad as facing an unpredictable position is playing an unpredictable opponent. Less experienced players “don’t know what to be afraid of,” as Magnus Carlsen put it .

“So they play without fear, without prejudice, and that’s sometimes difficult to face,” the world champion said.

Be yourself

A David may think to himself, “Grandmaster Goliath knows my favorite openings much better than me. I should try something new.”

Wrong. As GM Alex Yermolinsky said, “Nothing makes a GM happier than when his less experienced opponent gets ‘creative’ from the very first moves.”

“If you think your openings are good, play them against anyone, especially grandmasters!” he advised.

And the fourth guideline is:

Bend, don’t break

The longer that a lower-rated player can put up significant resistance, the greater the chance that his opponent will err. Goliaths get tired just like anyone else.

This doesn’t mean you should play on a rook down. It means you should make it as difficult to win as possible for as long as possible.

Patay – Rubinstein

Merano 1924

Colle Opening D04

1 d4 d5 2 ♘f3 ♘f6 3 e3 ♗f5 4 ♗d3 e6 5 ♘e5 ♘bd7 6 ♘d2 ♗d6 7 f4 0-0 8 ♘df3 ♘e4 9 0-0 h6 10 ♘xd7 ♕xd7 11 ♘e5 ♕e8 12 c4 c6 13 c5 ♗c7 14 b4 f6 15 ♘f3 a5! 16 bxa5 ♖xa5 17 ♕b3 ♕a8 18 a3 b6! 19 ♘d2 bxc5 20 ♘xe4 c4! 21 ♗xc4 ♗xe4 22 ♗d3 ♖b8 23 ♕c2 ♗xd3 24 ♕xd3 ♖ab5 25 ♖f2 ♖b3 26 ♕d1 ♕a6

Black has a clear positional advantage based on White’s weak a-pawn and bad bishop and Black’s control of the b-file and the prospect of opening lines with ... c5 and/or ... e5.

Many of Akiba Rubinstein’s master opponents would have lost if they were handling the White pieces now. The obscure player of the White pieces finds ways to prolong – and complicate.

27 a4 ♗a5! 28 ♖c2! ♗c3 29 ♖aa2 e5! 30 fxe5 fxe5 31 h3!? exd4 32 exd4

32 ... ♕c4?

Black’s last move seems to win the d4-pawn. But the superior 32 ... ♕b6! would have won after 33 ♗e3 ♖b1 or 33 ♔h1 ♕xd4 (33 ... ♗xd4 34 a5 is less clear) 34 ♕xd4 ♗xd4 35 ♖xc6 ♖e8! and ... ♖e1+.

33 ♔h2! c5?

Black is looking for more than the favorable endgame of 33 ... ♕xd4! 34 ♕xd4 ♗xd4 35 ♖xc6 and now 35 ... ♗e5+! 36 ♔g1 ♗g3. He may not win then. But it’s the best he can get now.

Rubinstein saw that 33 ... c5 34 dxc5 allows 34 ... ♗e5+! (35 ♔g1 ♖d3! and wins because of 36 ♕g4 ♕xg4 37 hxg4 ♗g3!, threatening ... ♖d1 mate). What he misjudged was:

34 ♗f4!

Now 34 ... ♖f8 35 ♗e5! allows White’s pieces to get active.

A draw would be likely after 35 ... cxd4 36 ♕g4 ♖b7 37 ♕e6+. For example, 37 ... ♖bf7 38 ♖f2. Or 37 ... ♖ff7 38 ♗xd4! ♕xd4 39 ♕c8+. Or 37 ... ♔h7 38 ♖f2.

34 ... ♖e8

So that 35 ♗e5 can now be met by 35 ... ♖xe5! 36 dxe5 ♗xe5+ 37 ♔h1? ♕f4 and wins, or 37 ♔g1 ♕e4!. But Black is entering a death spiral.

35 ♕h5! ♖e4? 36 ♗e5 cxd4? 37 ♖f2! ♖xe5

Or 37 ... ♖b7 (to stop ♕f7+) 38 ♕e8+ ♔h7 39 ♖f8.

38 ♕xe5 ♖b7? 39 ♕e8+ ♔h7 40 ♖f8 Black resigned.

Of course, following these four guidelines won’t guarantee an upset. In fact, it is often impossible to follow all of them because they contradict one another.

If you are better at endgames than tactical middlegames, “Be yourself” tells you to trade queens. That may be the opposite of playing actively or breeding chaos. Here’s a remarkable example:

Badrakh Galmandakh – Alexander Motylev

Gibraltar 2015

Irregular Opening A00

1 d3 d5 2 e4?!?

White, a minor Mongolian master, had opened the same way, against a grandmaster opponent who outrated him by 400 points, at the previous year’s Gibraltar tournament.

Black avoided the endgame with 2 ... e6?! and later made a promising sacrifice of his queen for a rook and bishop. But White didn’t break and agreed to a draw – on the 129th move.

2 ... dxe4 3 dxe4 ♕xd1+ 4 ♔xd1 e5 5 ♗e3 ♘f6 6 f3

The truth is that this is a very hard position for Black to win, even with a 410-point rating edge. White has no weaknesses. His king is not a significant target with queens traded.

6 ... ♘bd7 7 ♘d2 a5 8 a4 ♗c5 9 ♘c4 ♗xe3 10 ♘xe3 ♘c5 11 ♘c4 ♘fd7 12 ♘h3 ♔e7 13 c3 ♘b6?!

This is a curious decision. Black damages his queenside pawn structure – and concedes d5 to White’s pieces – in the hopes of generating strong rook-play on the c-file.

14 ♘xb6 cxb6 15 ♗c4 ♗d7 16 b3 ♖ac8 17 ♗d5! ♖c7

Black repeatedly passed up the pawn-wrecking ... ♗xh3. What was he afraid of?

Perhaps positions like 17 ... ♗xh3 18 gxh3 ♘e6 19 ♔c2 ♖c7 20 ♖hg1 g6 when 21 ♗xe6 ♔xe6 22 ♖ad1 brings about a rook endgame in which his winning chances are problematic.

18 ♘f2 ♖fc8 19 ♔c2 f5? 20 c4!

Black certainly couldn’t be complacent, over-confident or expecting to win quickly any more. Nevertheless, he still has some Goliath weaknesses.

20 ... fxe4 21 ♘xe4 ♘a6 22 ♔b2 ♘b4 23 ♖ad1 ♗f5? 24 ♖he1? ♖d8 25 ♘g3

Black is beginning to miscalculate – allowing 24 ♗xb7! ♖xb7 25 ♘d6.

Now he had to try something like 25 ... ♗c2 26 ♖d2 ♔f8, since 27 ♖xe5 ♘d3+ is a marginal White edge.

25 ... ♘d3+? 26 ♔c3 ♘xe1 27 ♘xf5+ ♔f6 28 ♘e3!

This is apparently what Black overlooked. The Black knight is trapped. Although 28 ... ♘xg2 29 ♘xg2 gave him approximate material equality, White had most of the winning chances. Black conceded on the 77th move.

The idea for this book – and its title – came from Batsford’s themselves. In choosing 50 instructive upsets I sought games in which the stronger player was at least 200 rating points better than his opponent. In several cases, the difference was much greater. You can enjoy the games in any of several ways.

First, you can root for the underdogs. We all like to see high-rated players being humbled. It’s schach-schadenfreude.

Second, there are techniques employed in these games that may apply to your own games when playing a stronger opponent.

And, finally, these games are also a warning of what not to do when you are the one playing a much weaker opponent. Some days you will be a David and some days you will be a vulnerable Goliath.

It’s not just an upset when a world-class player is beaten by a much weaker player. It’s a historic event. The next chapter shows how super-Goliaths were slain.

Even though they were measurably stronger than other upset victims we’ll see, they fell for many of the same reasons outlined in the first chapter. The Davids relied on active play or they fostered chaos. They exploited complacency, impatience, fear of drawing, and miscalculation.

Chapter Two:

When Titans Fall

1 Walter Grimshaw – Wilhelm Steinitz

London 1870

Scotch Game, Steinitz Variation C45

Few tournament players will recognize the name Walter Grimshaw. But every lover of composed problems certainly would.

His fame is secured by the “Grimshaw theme”: Black pieces are forced to interfere with one another and allow a mating move. Grimshaw is also credited with winning the first-ever problem solving tournament in Great Britain, in London in 1854.

But he was also a strong over-the-board player, as this game attests. It was apparently played at the celebrated London chess hangout Simpson’s Divan.

1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 ♘c6 3 d4 exd4 4 ♘xd4 ♕h4

This last move was a Steinitz specialty that is periodically revived.

It violates general opening principles. But as 19th century players knew well, abstract notions about a position are always secondary to what’s happening on the board. In this case, Black’s threat of 5 ... ♕xe4+ takes center stage.

5 ♘b5!

Play actively! Grimshaw’s move ignored Black’s threat by making a bigger threat (6 ♘xc7+).

If White were following the general principles that Black violated, he would choose 5 ♘c3.

Then the 5 ... ♗b4 pin renews the ... ♕xe4+ threat. Black would stand well after 6 ♘b5? ♗a5.

Better is 6 ♗e2 ♕xe4 7 ♘b5 ♗xc3+ 8 bxc3 ♔d8, when Black has a better version of what happens in the game

Bear in mind that Steinitz was well aware of 5 ♘b5. Databases show that he eventually defended this position at least nine times. He scored seven wins and one draw, with only one loss.

5 ... ♕xe4+? 6 ♗e3

Today 6 ♗e2 is more popular. Steinitz liked to meet that with 6 ... ♗b4+ and, if 7 ♗d2, then 7 ... ♔d8.

6 ... ♗b4+ 7 ♘d2!

This is superior to 7 c3 because if Black defends c7 with 7 ... ♕e5?, he stumbles into 8 c3 and 9 ♘c4!.

Also 7 ... ♔d8? loses the bishop to 8 c3!, because 9 ♘xe4 is the main threat.

7 ... ♗xd2+ 8 ♕xd2 ♔d8

Steinitz is credited with saying that an extra pawn is worth a little trouble. But it’s hard to imagine how he thought he could complete development. He was betrayed by over-confidence in his own opening and chess philosophy.

9 0-0-0 ♕e6

This would have been the shortest loss by a world champion after 9 ... d6?? 10 ♘xc7! resigns.

Steinitz’s move protects the key d6 square and eyes ... ♕xa2. But White has been ignoring Black’s threats since 5 ♘b5! and he can continue to do so.

10 ♗f4! d6 11 ♗xd6!

White also wins after 11 ♘xc7 ♔xc7 12 ♗xd6+ (12 ... ♔b6 13 ♕c3! and 12 ... ♔d8 13 ♗f8+ and ♗xg7 or 13 ♗b5). But the text is more punishing.

11 ... cxd6 12 ♘xd6

Some computers prefer 12 ♕g5+ followed by ♖xd6+ or ♕xg7. The text allows Black to play a lost endgame after 12 ... ♔c7 13 ♗c4 ♕h6 14 ♘xf7 ♕xd2+.

12 ... ♕xa2

But Steinitz evidently wanted the game over. White can mate in nine moves with 13 ♘xc8+ or in six (if Black meets 13 ♘b5+ with 13 ... ♕d5).

13 ♘b5+! ♔e8 14 ♘c7+ ♔f8 15 ♕d6+ ♘ge7 16 ♕d8+! ♘xd8 17 ♖xd8 mate

This game was so embarrassing that in later years Steinitz repeatedly used his International Chess Magazine to deny that it happened. “Bogus manufactured forgery” were his words. However, eyewitnesses eventually stepped forward to say, yes, it occurred. They all saw a Goliath mated in 17 moves.

2Milton Otteson – Bobby Fischer

Milwaukee 1957

Reti Opening A05

Bobby Fischer had already earned international fame with his “Game of the Century” in 1956. He was a month away from winning the US Open when he played this game in a holiday weekend tournament.

He began it impressively, outplaying his opponent in the opening, seizing a positional advantage by move 12 and then a slight material edge five moves later.

But Fischer’s Achilles heel was a tendency to relax when he felt his position was won. His opponent capitalized on this complacency.

1 ♘f3 ♘f6 2 g3 g6 3 b4 ♗g7 4 ♗b2 0-0 5 ♗g2 d6 6 d4 e5!

This is a good way of handling this and the similar positions with 3 b3. Black threatens to gain space and a small edge with 7 ... e4.

7 dxe5 ♘g4 8 ♘bd2

8 ... ♘c6!

Fischer’s choice is more ambitious than 8 ... ♘xe5 9 ♘xe5 dxe5 (or 8 ... dxe5 9 h3 e4 10 ♗xg7 exf3 11 ♘xf3). Fischer scored 6-1 in his other games in this tournament and was seeking more than equality in this one.

9 b5 ♘cxe5 10 ♘xe5 ♘xe5 11 0-0

His goal was to win the two-bishop edge with ... ♘f3+ followed by ... ♗xb2.

If White protects his b2-bishop, 11 ♖b1, he runs into other problems, such as 11 ... a6! 12 a4 axb5 13 axb5 ♕e8! (14 c4? ♘d3+).

11 ... ♘f3+! 12 ♗xf3! ♗xb2 13 ♖b1 ♗g7 14 ♘c4

Black would like to complete development quietly. But after 14 ... ♗e6 15 ♘a5! his queenside comes under fire.

14 ... ♗h3! 15 ♖e1 ♗c3

Black wants to convert the “2Bs” into a harder currency, the Exchange. He would also have good winning chances after 16 ♘d2 ♗e6 17 a4 d5 or 17 ♗xb7 ♖b8, for example.

16 ♗xb7!? ♗xe1 17 ♕xe1

Now 17 ♗xa8?? ♕xa8 loses a piece because of the threat of ... ♕g2 mate.

17 ... ♖b8 18 ♗f3 ♕g5 19 a4

Does a trade of bishops help White or Black? The answer is Black in variations such as 19 ... ♗g4 20 ♗xg4? ♕xg4.

But from now White has the good square c6 – and later d5 – for his bishop. Preserving material (19 ... ♗g4 20 ♗c6!) preserves his chances to make matters more double-edged.

19 ... ♕c5 20 ♘e3 ♗e6!

Black’s rooks can’t act like rooks and that means the extra Exchange isn’t significant yet. For example, 20 ... ♖fe8 21 ♘d5 ♔g7 looks right, to rule out ♘f6+ tricks.

But then 22 ♖b3! followed by 23 ♕a1+ or 23 ♖c3 is suddenly looking good for White.

21 c4! a6?

Not 21 ... ♗xc4?? 22 ♖c1! d5 23 ♗xd5. It’s not clear what Fischer had in mind since a pawn exchange on b5 will hand his opponent an outside passed pawn.

22 ♖d1 axb5 23 cxb5! ♗b3 24 ♖c1 ♕d4

Suddenly White is better. Or he would have been, if he had realized the value of his passed pawn.

With 25 ♗c6! it would threaten to advance to a6. For instance 25 ... f5 26 a5 f4 27 gxf4 ♖xf4 28 a6.

To play 25 ♗c6! he would have to see the tactics that protect the a-pawn.

They are 25 ... ♗xa4 26 ♖c4 ♕a7 27 ♕a1! and 25 ... ♕xa4 26 b6!, threatening ♗xa4 or bxc7.

Instead, he opted for another anti-Goliath strategy, making threats on the opposite wing.

25 ♖xc7!? ♕xa4 26 ♕c3

Now a capture on b5 permits 27 ♘g4! followed by ♘h6 mate or a strong ♘f6+. The position is getting murky.

26 ... ♗e6 27 ♗c6 ♖fc8

When his position declines, a Goliath sets traps.

This is a neat one – 28 b6 ♖xc7 29 bxc7 looks like it wins for White.

But 29 ... ♖b3! is solidly in Black’s favor (30 ♗xa4? ♖xc3, 30 ♕c1 ♕b4 or 30 ♕c2 ♕a1+ 31 ♔g2 ♖b1).

28 ♖e7! d5

Returning the Exchange, 28 ... ♖xb5 29 ♗xb5 ♕xb5, offered no real winning chances. Only slightly better is 28 … ♕xb5 (29 ♖e8+ ♖xe8 30 ♗xb5 ♖xb5).

29♕f6!♖xc6?

The threats were 30 ♘xd5 and 30 ♖xe6. But they should have been stopped by 30 … ♕e4!.

Fischer seemed confused about what to expect around this time. He didn’t want a draw last move (28 … ♖xb5 or 28 … ♕xb5). But now he wanted one and must have thought that giving back material would do the trick.

30 bxc6♕xc6 31♘g4!

31 ...♕c1+?

He must have seen that 31 … ♖b7 stops the threat of 32 ♘h6+ ♔f8 33 ♖xf7+.

But he probably talked himself out of it because of 32 ♘h6+ ♔f8 33 h4 and 33 ... ♖b1+ 34 ♔h2.

What he missed is the insertion of 31 … ♖b1+! turns 32 ♔g2 ♖b7! into a trap.

The difference is that 33 ♘h6+ ♔f8 34 h4?? loses the queen to 34 … ♗h3+!.

That doesn’t end the tactics. White might have found 33 ♕e5!

That is based on 33 … ♖xe7?? 34 ♘h6+ ♔f8 35 ♕h8 mate. White would have kept winning chances after 33 … ♔f8 34 ♖xb7 ♕xb7 35 ♕h8+ and ♕xh7.

But now he gets a once-in-a-lifetime chance to mate a future world champion.

32♔g2♖f8

33 ♖xe6

This is good enough to win. But 33 ♖c7! would have made 33 ... ♕d2 34 ♖c2! ♕xc2 35 ♘h6 mate one of the prettiest-ever defeats of Fischer.

33 ... fxe6 34 ♕xe6+ ♔g7 35 ♕e5+ ♔f7 36 f4 ♖c8 37 ♘h6+?

This and the errors that follow look like the spawn of time pressure. White should have won quickly with 37 ♕f6+ ♔e8 38 ♘e5!.

37 ... ♔f8 38 ♕h8+ ♔e7 39 ♕xh7+ ♔d6 40 ♕xg6+ ♔c5 41 ♕d3 ♕c4 42 ♘g4 ♖g8?

There were slim drawing chances available in the 42 ... ♕xd3 43 cxd3 ♔d4 endgame.

43 ♘e5 ♕xf4? 44 ♕c3+ ♔b5 45 ♕c6+ ♔a5 46 ♕xd5+ ♔a4 47 ♕xg8 ♕xe5 48 ♕c4+ ♔a3 49 h4 Black resigned.

3Artiom Samsonkin – Hikaru Nakamura

Toronto 2009

Sicilian Defense, Kan Variation B43

Hikaru Nakamura was already a world-class grandmaster when he met a 19-year-old Canadian student midway through a large Swiss System open tournament. One careless move in the opening should have warned Black that he was entering must-calculate territory. Only two mistakes were enough to lose.

1 e4 c5 2 ♘f3 e6 3 ♘c3 a6 4 d4 cxd4 5 ♘xd4 ♕c7 6 ♗d3 ♗e7 7 0-0 ♘f6 8 a4 b6 9 ♕e2 d6

Black has been keeping his options wide open. He didn’t commit his d-pawn until he needed it to stop 10 e5. He doesn’t make a decision about his QN until he’s decided against ... ♘c6. And he doesn’t castle early because it would have given White a reason for g2-g4-g5!.

10 f4 ♗b7 11 ♗d2 ♘bd7 12 ♖ae1 ♘c5

That stay-flexible policy seems to be working because 13 e5? gives Black a small pull after 13 ... ♘xd3! 14 ♕xd3 dxe5 15 fxe5 ♘d7.

That fits in with a Sicilian rule of thumb: If e4-e5 doesn’t generate immediate White threats, it fizzles out quickly.

Well, if White can’t exploit Black’s failure to castle with e4-e5, what about forcing matters on the queenside?

13 b4!? ♘xd3 14 cxd3

The test of White’s idea is 14 ... 0-0 15 ♖ac1 ♕d7. The queen move avoids a discovered rook attack on it (16 ♘d5).

But what’s next? White doesn’t achieve anything by doubling rooks, 16 ♖c2 ♖fc8 17 ♖fc1 ♗f8.

More adventurous is 16 g4 and then 16 ... ♘e8 17 f5. But 17 ... d5! gets to a very double-edged endgame after 18 fxe6 fxe6 19 exd5 exd5 20 ♕e6+ that Black may be happy to play.

14 ... ♘d7? 15 ♖c1 ♕d8

Black’s knight retreat is hard to explain. There was no reason to fear e4-e5.

16 f5!

White wants to create either a target on e6 or an outpost on f5 (16 ... exf5? 17 ♘xf5).

After 16 ... ♗f6! 17 ♗e3 e5 18 ♘b3 he would have chances on either wing, with ♘d2-c4 on the queenside or ♕g4 on the kingside.

Black has to be careful because he is behind in development. For example, 17 ... ♕e7 (instead of 17 ... e5) would allow 18 fxe6 fxe6 19 ♕h5+ g6 20 ♕h3.

If Black counters the 21 ♘xe6 threat with 20 ... ♖c8 he’d get a Goliath-sized surprise from 21 e5! (21 ... ♘xe5 22 ♘d5! ♗xd5 23 ♖xc8+ or 21 ... ♗xe5 22 ♘d5! exd5 23 ♖xc8+ ♗xc8 24 ♘c6!).

16 ... e5?

What happens in the next three moves looks impossible for a David to calculate. It isn’t because:

(a) An improving David would know that ♘e6 (or ♘xe6) is a common sacrificial theme in the Sicilian Defense.

(b) He could see White’s most forcing moves that follow 17 ♘e6.

(c) He would then see that Black’s replies are more or less forced.

17 ♘e6! fxe6 18 ♕h5+ g6

Or 18 ... ♔