15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

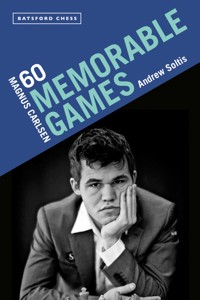

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Following on from the long success of one of the most important chess books ever written, Bobby Fischer: My 60 Memorable Games, renowned chess writer Andrew Soltis delivers a book on today's blockbuster chess player Magnus Carlsen. Magnus Carlsen has been the world's number one player for more than a decade, has won more super-tournaments than anyone ever and is still in his prime. He is the only player to repeatedly win the world championships in classical, speed and blitz chess formats. This book details his remarkable rise and how he acquired the crucial skills of 21st-century grandmaster chess He will defend his world championship title this autumn and if he wins, it will set a record of five championship match victories. This book take you through how he wins by analysing 60 of the games that made him who he is, describing the intricacies behind his and his opponent's strategies, the tactical justification of moves and the psychological battle in each one.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 553

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Magnus Carlsen:60 Memorable Games

Andrew Soltis

Contents

Introduction: What Made Magnus

1 Carlsen – Harestad, Copenhagen 2003

2 Zimmerman – Carlsen, Schwarzacher Open 2003

3 Carlsen – Laqua, Schwarzacher Open 2003

4 Carlsen – Diamant, Halkidiki 2003

5 Carlsen – Stefansson, Aeroflot Festival, Moscow 2004

6 Djurhuus – Carlsen, Norwegian Championship 2005

7 Carlsen – Predrag Nikolić, Wijk aan Zee 2005

8 Brynell – Carlsen, Gausdal Bygger’n Masters 2005

9 Jobava – Carlsen, Skanderborg 2005

10 Carlsen – Vescovi, Wijk aan Zee 2006

11 Agdestein – Carlsen, Norwegian Championship 2006

12 Carlsen – Nunn, Youth vs. Experience, Amsterdam 2006

13 Carlsen – Ivanchuk, Morelia-Linares 2007

14 Carlsen – Aronian, Candidates match, Elista 2007

15 Mamedyarov – Carlsen, Wijk aan Zee 2008

16 Topalov – Carlsen, Morelia-Linares 2008

17 Kramnik – Carlsen, Wijk aan Zee 2008

18 Carlsen – Grischuk, Linares 2009

19 Anand – Carlsen, Melody Amber (blindfold), Nice 2009

20 Carlsen – Topalov, Sofia 2009

21 Carlsen – Leko, Nanjing 2009

22 Aronian – Carlsen, Melody Amber (blindfold), Nice 2010

23 Carlsen – Bacrot, Nanjing 2010

24 Smeets – Carlsen, Wijk aan Zee 2011

25 Carlsen – Nakamura, Medias 2011

26 Carlsen – Gelfand, Tal Memorial, Moscow 2011

27 Carlsen – Nakamura, Wijk aan Zee 2011

28 Radjabov – Carlsen, Moscow 2012

29 Carlsen – Caruana, Sao Paulo 2012

30 Carlsen – Anand, Sao Paolo 2012

31 Carlsen – Judith Polgar, London 2012

32 Carlsen – Harikrishna, Wijk aan Zee 2013

33 Anand – Carlsen, World Championship, Chennai 2013

34 Carlsen – Caruana, Shamkir 2014

35 Carlsen – Anand, World Championship, Sochi 2014

36 Nakamura – Carlsen, Zürich 2014

37 Carlsen – Wojtaszek, Olympiad, Tromsø 2014

38 Carlsen – So, Sinquefield Cup, St. Louis 2015

39 Carlsen – Naiditsch, Baden Baden 2015

40 Carlsen – Vachier-Lagrave, Shamkir 2015

41 Carlsen – Nakamura, London 2015

42 Carlsen – Li Chao, Qatar Masters, Doha 2015

43 Anand – Carlsen, Baden – Baden 2015

44 Caruana – Carlsen, Sinquefield Cup, St. Louis 2015

45 Carlsen – So, Bilbao 2016

46 Carlsen – Karjakin, World Championship, New York 2016

47 Karjakin – Carlsen, World Championship, New York 2016

48 Carlsen – Aronian, Paris Blitz 2016

49 Eljanov – Carlsen, Isle of Man Masters, Douglas 2017

50 Carlsen – Ding Liren, St. Louis 2017

51 Dreev – Carlsen, World Cup, Tbilisi 2017

52 Carlsen – Wojtaszek, Shamkir 2018

53 Adhiban – Carlsen, Wijk aan Zee 2018

54 Carlsen – Jones, Wijk aan Zee 2018

55 van Foreest – Carlsen, Wijk aan Zee 2019

56 Carlsen – Rapport, Wijk aan Zee 2019

57 Svidler – Carlsen, Baden – Baden 2019

58 Vachier-Lagrave – Carlsen, Sinquefield Cup, 2019

59 Giri – Carlsen, Zagreb 2019

60 Firouzja – Carlsen, Wijk aan Zee 2020

Index of Opponents

Index of Openings

ECO Openings Index

Index of Middlegame Themes

Index of Endgames

Introduction:What Made Magnus

As 2020 began Magnus Carlsen celebrated ten straight years as the world’s highest rated player. He held three world championship titles, in blitz, rapid and “classical” chess, an unprecedented achievement. Within days of the new year he broke the record for playing more than 107 straight games without a loss.

The term “super-tournament” has no precise meaning. But it has come to mean a round robin with classical time controls, in which each player is an elite grandmaster. In recent years the Sinquefield Cup, Norway Chess, Wijk aan Zee and the Gashimov Memorial have become synonymous with super-tournament.

Bobby Fischer never won a super-tournament. Garry Kasparov won outright or tied for first place in 35 super-tournaments in his nearly-30-year career. His fans said this was further evidence that he was the greatest player in chess history.

But Magnus Carlsen won some 40 super-tournaments, plus another 14 “super” speed tournaments before he was 30.

“What makes Carlsen different?” is a good question. But a better one is: How did he make himself different?

The simplest answer is that he played an extraordinary amount of chess and did it long before he was a master. One on-line database, Chessgames.com, contains 1,000 games he played before he was 17.

In contrast, Kasparov played his 1,000th game when he was 27 – and had already been world champion for five years, according to the same source.

Of course, large numbers of games, even of a famous player, are typically missing from databases, especially in their early years. But the 1,000th game of Fabiano Caruana preserved by Chessgames.com came after he had been competing in tournaments for 16 years. Carlsen did it in half that time.

Playing a lot doesn’t necessarily teach. What did Carlsen learn from so much chess?

Playability

Perhaps the most important is the ability to judge which positions are easier to play than others.

Carlsen – Vasily Ivanchuk

Sao Paolo 2011

Nimzo-Indian, Three Knights Variation (E21)

1 d4 ♘f6 2 c4 e6 3 ♘c3 ♗b4 4 ♘f3 b6 5 ♕c2 ♗b7 6 a3 ♗xc3+ 7 ♕xc3 ♘e4 8 ♕c2 f5 9 g3 ♘f6 10 ♗h3 0-0 11 0-0 a5 12 ♖d1 ♕e8 13 d5 ♘a6 14 ♗f4 exd5 15 ♗xf5 dxc4 16 ♘g5! ♕h5 17 ♖xd7! ♔h8 18 ♖e7? ♘d5 19 ♗g4 ♕g6 20 ♘f7+ ♔g8 21 ♗f5 ♕xf5 22 ♕xf5 ♘xe7 23 ♘h6+ gxh6 24 ♕g4+ ♘g6 25 ♗xh6

Carlsen missed opportunities to put the game away earlier (18 ♖ad1! ♘xd7 19 ♖xd7, for example).

His comment here is revealing: “White certainly has the easier game.”

That is, it is easier to find good moves for White than it is for Black. And it is easier for Black to err than for White.

This was borne out by the rest of the game: 25...♖f7 26 ♖d1 ♖e8 27 h4! ♘c5 28 h5 ♗c8 29 ♕xc4 ♘e5 30 ♕h4 ♘c6? (30...♘e6!) 31 ♖d5! ♘e6 32 ♕c4 ♘cd8? 33 ♕g4+ ♘g7 34 ♕xc8 Resigns.

Now you might say: “So what? Carlsen wasn’t trying to evaluate the position in the diagram. He was just stating a personal opinion.”

Oh, but he was evaluating the position. He was judging it in terms of playability. That is not a precise concept. There is no metric to quantify it and computers cannot appreciate it. But in real-life situations, playability is as valid as more familiar ways of evaluating a position, such as piece mobility or pawn structure.

Over and over in Carlsen’s notes to his games he said the move he chose was the one that lead to an “easier” position, the “more pleasant” game, a “more comfortable” one. Playability was a crucial factor for him in deciding whether to take an irrevocable step, such as sacrificing a pawn or the Exchange.

Karjakin – Carlsen

World Championship match, 3rd playoff game, New York 2016

White has just played 30 ♖a3. Computers recommend 30...♕d8, 30...♕b8, 30...♕c8 and 30...♗h4. But they can’t find a significant advantage after any of these moves.

Carlsen chose 30...e4. It forced a trade of bishops, allowed him to maintain his knight on e3 and opened the dominating square e5 to his queen.

Some engines say his winning chances declined, slightly or to a large degree, after 31 dxe4 ♗xc3 32 ♖xc3 ♕e5.

But grandmasters around the world who followed the game on-line smiled when they saw 30...e4!. They knew that it was exactly the kind of move you should play in such a position. Regardless of what machines say, Black’s winning chances were soaring. The position was simply much easier for him to play.

They were right, as Game 47 shows. If there is any single Magnus move that saved the world championship title he first earned in 2013, it was 30...e4!.

Universality

What else did his early tournament experience teach Carlsen? An answer is remarkable versatility.

Every great player has his kind of positions, the ones he knows best from past experience. But every great player, and this includes world champions, has other positions that he does not know as well and consequently plays less well.

Very early in his career Carlsen amassed an extraordinary amount of experience in virtually every opening, every pawn structure and every endgame.

Versatility is not just a feature of his play, according to Vishy Anand. It is his main strength. Magnus is “capable of being many different players,” Anand told the New Yorker magazine. “He can be tactical. He can be positional.”

In another interview Anand was asked to compare Carlsen with an earlier paragon of versatility, Anatoly Karpov. Anand knew them both. He had played nearly 100 games with Karpov and well over 100 with Carlsen. “I think Carlsen’s much more universal,” Anand said. “There haven’t been many such players at all, perhaps Spassky in his best years.”

Like almost every 1 e4 player, Carlsen learned how to play the Ruy Lopez. But he also played the Ponziani Opening, the Bishop’s Opening and the Vienna Gambit as well as the exotics such as 1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 ♘c6 3 d3, the Four Knights Game with 4 a3, the King’s Gambit Accepted with 3 ♘c3 and even 1 e4 e5 2 ♕h5 (in rapids and blitz).

As Black he defended the Ruy Lopez, as do most of the world-class players of the last half century. But he also adopted the Philidor’s Defense and brought 1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 ♘c6 3 ♗b5 ♗b4!? out of mothballs. He used oddities against top-notch opponents, such as meeting Vladimir Kramnik’s 1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 ♘c6 3 ♗c4 ♘f6 4 d3 with 4...♕e7 5 ♘c3 ♘a5. In the 2019 Norway Chess (blitz) tournament he defeated Caruana with 1 e4 g6 2 d4 ♘f6 3 e5 ♘h5.

Of course, there have always been strong grandmasters who varied their openings. But Carlsen weaponized his versatility. It was a huge asset when playing rivals who spent enormous amounts of time preparing to play him.

Most elite grandmasters are obsessed with openings. Hikaru Nakamura spends about 80 percent of his study time preparing his first moves for future opponents. He spends another 10 percent reviewing his games and the final 10 percent on endgames, he said on Reddit.com in 2014.

But preparing for Magnus is almost impossible. Since he and Nakamura first met over the board in 2006, Carlsen defended against his 1 d4 with the King’s Indian, Nimzo-Indian, Grünfeld, Bogo-Indian and Queen’s Indian Defenses and the Slav and various other versions of the Queen’s Gambit Declined.

He “seems to feel at home in all” kinds of positions, Jan Timman said. “He is not hampered by the prejudices that used to be part and parcel of classical chess,” Timman added. One of Carlsen’s seconds, Jon Ludwig Hammer, joked that a regular opening for Magnus means one he has played more than twice in a row.

Against lesser mortals, Carlsen’s opening versatility can be devastating. In the final days of 2019, he won this game.

Carlsen – Bartosz Socko

World Blitz Championship, Moscow 2019 Queen’s Indian Defense, Fianchetto Variation (E15)

1 d4 ♘f6 2 c4 e6 3 ♘f3 b6 4 g3 ♗b7 5 ♗g2 c5 6 d5

This quasi-gambit dates back at least to Fritz Sämisch in the 1920s.

6...exd5 7 cxd5!?

But Sämisch played 7 ♘h4 and that is still the standard move.

7...♗xd5 8 ♘c3 ♗xf3

Bartosz Socko – and his wife, IGM Monika Socko – were among the world’s experts at defending the Black position after 6...exd5. He didn’t show it.

9 ♗xf3 ♘c6 10 ♗f4 ♗e7 11 0-0 0-0 12 e3 ♘e8 13 h4!

For his pawn, Magnus has kingside prospects (♕c2/♘g5) and potential pressure on the center (♕a4/♖ad1).

The rest was inexactly played – well, it was a blitz tournament. But Black was clearly uncomfortable, even in an opening he knew well.

13...h6 14 h5 ♘c7 15 ♕a4 ♘e6 16 ♖ad1 ♖c8 17 ♘d5 ♘xf4 18 gxf4 ♖e8 19 ♔g2! ♗f8 20 ♖g1 ♘e7?? (Black remains worse after the computer-recommended 20...♘b4 21 ♘xb4 and 20...b5 21 ♕xb5 ♖b8 21 ♕e2) 21 ♘f6+! gxf6 22 ♖xd7 b5 23 ♕xa7 ♖a8 24 ♖xd8 Resigns.

Carlsen plays so well in so many different openings that the choice of the first moves seems irrelevant to him. When his game with Kramnik began at Wijk aan Zee 2010, he closed his eyes and remained motionless for nearly two minutes. He was trying to choose between 1 e4 and 1 d4. Kramnik joked afterward that he wondered if he should wake him up.

Before a game two years later at Wijk aan Zee, Carlsen asked his father to pick a letter from “a” to “h.” He chose “f.” So Carlsen played 1 ♘f3 that day and defeated Vugar Gashimov.

Memory

There are other attributes that made Carlsen exceptional. For example, he developed a remarkable memory very early. By age five he reputedly could recite the populations of all 422 Norwegian municipalities.

Chess memory is a more specific brand. Carlsen’s memory of middlegame themes and not just opening variations was noticeable in his first master-level results.

Carlsen – Adnan Orujov, Peniscola 2002, began 1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 ♘c6 3 d4 exd4 4 ♘xd4 ♘f6 5 ♘xc6 bxc6 6 e5 ♕e7 7 ♕e2 ♘d5 8 c4 ♗a6 9 b3 0-0-0 10 g3 ♖e8 11 ♗b2 f6 12 ♗g2 fxe5 13 0-0.

These moves look odd, if not bizarre. But the little previous experience that there was had shown that White stands well if he carries off the maneuver ♕d2-a5.

The game confirmed this: 13...g6 14 ♕d2! ♘b6 15 ♕a5 ♔b7 16 ♗a3 ♕f6 17 ♗xf8 ♖hxf8 18 ♘c3 ♕e7 19 ♘a4!.

The threat is 20 ♘c5+. Black would be lost after 19...♘xa4 20 bxa4 followed by ♖ab1+ (20...♗xc4 21 ♖ab1+ ♔a8 22 ♕xc7 ♖b8 23 ♗xc6+ or 22...♗a6 23 ♖fd1).

Carlsen would be the first to admit that his rivals prepare their openings better than he does. They often win short games while he is playing 70+ moves. This was an exception:

19...d6 20 ♗xc6+! ♔xc6 21 ♕xa6 e4 22 c5 dxc5 23 ♘xc5 ♔xc5 24 ♖fd1 ♕e5

25 b4+ ♔xb4 26 ♖ab1+ ♔c3 27 ♖b3+ ♔c2 28 ♕e2 mate.

Gata Kamsky ridiculed the role that openings played in the games of today’s elite players. “All they have to do is simply memorize those preparations, get to the board and just show the preparation,” he said in New In Chess in 2011 “There is no chess skill involved in that! It’s just all memory, and that’s it.”

This is not Carlsen. He does not sit down and memorize dozens of inexplicable moves that a computer tells him to play. Rather, he has a sponge-like memory that picks up and retains striking ideas from games he has seen. This became noticeable after the game Carlsen – Sipke Ernst from the C group of Wijk aan Zee 2004:

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 ♘c3 dxe4 4 ♘xe4 ♗f5 5 ♘g3 ♗g6 6 h4 h6 7 ♘f3 ♘d7 8 h5 ♗h7 9 ♗d3 ♗xd3 10 ♕xd3 e6 11 ♗f4 ♘gf6 12 0-0-0 ♗e7 13 ♘e4 ♕a5 14 ♔b1 0-0 15 ♘xf6+ ♘xf6 16 ♘e5 ♖ad8 17 ♕e2 c5

Magnus won in stunning style: 18 ♘g6 fxg6? 19 ♕xe6+ ♔h8 20 hxg6! ♘g8 21 ♗xh6 gxh6 22 ♖xh6+ ♘xh6 23 ♕xe7 ♘f7 24 gxf7 ♔g7 25 ♖d3 ♖d6 26 ♖g3+ ♖g6 27 ♕e5+ ♔xf7 28 ♕f5+ ♖f6 29 ♕d7 mate!

How much of this was “prep”—that is, what Carlsen had studied just before this game?

The answer he gave Lubosh Kavalek after the game was that he didn’t even know his opponent played the Caro-Kann: “Ernst left my preparation at move one!” Carlsen said.

When the opening unfolded he remembered that 17 ♕e2 was “book.” But it took him 25 minutes to figure out why.

And that’s how he remembered that 18 ♘g6 had been played before. The first new move was 24 gxf7!, improving over 24 ♕f6+, which had led to a draw in a previous game.

Other Factors

Another Carlsen strength that came from playing so much is psychological: He learned how to deal with losing.

Many Soviet-era players grew up believing that two draws were better than a win and a loss. A loss was a psychological blow that cannot be repaired quickly. “When you beat your opponent in a chess game, you destroy his ego,” as Kasparov said “For a time you make him lose confidence in himself as a person.” The agony of defeat far outweighs the thrill of victory, Soviet juniors were taught. After losing, a player needed to recover, perhaps by making a quick draw.

Carlsen’s rivals can be plagued by memories of defeat. Nakamura recalled his spectacular collapse against Carlsen at Zürich 2014. Computers said he had an advantage of greater than +6.00 for several moves and it grew to double digits. Then he lost. “I had nightmares about the Carlsen game for four days afterwards,” he said.

Carlsen has had bad periods. In the middle of his record non-losing streak in 2019-20, he suffered a meltdown in speed and blitz tournaments. “When things start to go wrong, it is easy to doubt oneself. I tried to play more aggressively rather than trying to play safer, but it doesn’t really seem to work out any more,” he said. “I am constantly doubting myself.”

But Magnus manages to recover from defeat more easily than his rivals. Tigran Petrosian used to say that he was more upset when his Spartak team lost at football than when he lost at chess. Carlsen is similar: “I get more upset at other things than chess,” he told Dylan Loeb McClain. “I always get upset when I lost at Monopoly.”

After he lost a game in his first high-profile tournament, Wijk aan Zee 2004, he won his next three games. He moved on to the Aeroflot Open and lost in the first round. Then he beat grandmasters in the next three games, beginning with this:

Carlsen – Sergey Dolmatov

Aeroflot Festival, Moscow 2004 Réti Opening (A04)

1 ♘f3 f5 2 d3 d6 3 e4 e5 4 ♘c3 ♘c6 5 exf5! ♗xf5 6 d4 ♘xd4 7 ♘xd4 exd4 8 ♕xd4 ♘f6? 9 ♗c4 c6 10 ♗g5 b5 11 ♗b3 ♗e7? 12 0-0-0 ♕d7 13 ♖he1 ♔d8

14 ♖xe7! ♕xe7 15 ♕f4 ♗d7 16 ♘e4 d5 17 ♘xf6 h6 18 ♗h4 g5 19 ♕d4 Resigns.

What else made Magnus? His speed chess experience gave him a better clock sense than anyone, perhaps anyone ever. When he and his opponent have only seconds left he has a superior feeling of which moves to play and how quickly to play them.

This is evidenced in two ways. First, he has been able to dominate the increasingly popular tie-breaking playoffs. He was “Mister Tie Break” as the Russian magazine 64 called him on its cover in January 2016. Between 2007 and 2019 he hadn’t lost such a major playoff.

Another valuable quality he acquired as a pre-teen is knowing how to swindle. He often outplayed opponents in bad and even lost positions. By the time he was 30 he had swindled more opponents than Mikhail Tal in his entire career.

Loek van Wely – Carlsen

Wijk aan Zee 2016 Grünfeld Defense (D83)

1 d4 ♘f6 2 c4 g6 3 ♘c3 d5 4 ♗f4 ♗g7 5 e3 0-0 6 ♖c1 ♗e6 7 cxd5 ♘xd5 8 ♘xd5 ♗xd5 9 ♗xc7 ♕d7 10 ♗g3 ♗xa2 11 ♘e2 ♗d5 12 ♘c3 ♗c6 13 h4 ♖d8 14 ♕b3 ♕f5 15 h5 e6 16 hxg6 hxg6 17 ♕d1 ♘d7 18 ♗d3 ♕a5 19 ♔f1 ♘f6 20 ♗e5 ♖ac8 21 ♕d2 ♘g4 22 ♗xg7 ♔xg7 23 f3 ♕g5?? 24 fxg4 ♖xd4 25 ♔e1 ♕e5 26 ♘e2 ♖xg4 27 e4

His piece sacrifice at move 23 was unsound and now he knew. He could try 27…♖h8 28 ♖xh8 ♔xh8 and grovel in a lost endgame after 29 g3 and 30 ♕c3.

But White was severely short of time. Magnus gambled on 27...♖xg2 and allowed 28 ♕h6+ ♔f6.

Fans who watched the game online were told by computers that 29 ♕h4+ g5 30 ♕h3! would trap the g2-rook and win.

But White played a natural defensive move, 29 ♖c3?.

After 29...♖d8! 30 ♕h3 ♕g5 31 ♖f1+ ♔g7 32 ♕f3 ♖d7 33 ♖f2 his advantage had evaporated.

A good swindler knows to retain material until there is a good reason to swap (not 33...♖xf2).

Carlsen’s 33...♖g4 immediately induced a collapse, 34 ♘f4 ♕h4 35 ♗e2? ♖g1+ 36 ♗f1 ♔g8 37 ♘e2? (37 ♘g2!) ♖xf1+! 38 ♔xf1 ♖d1+ 39 ♔g2 ♗xe4 White resigns.

Engines pointed out that 36...e5! was better and that 36...♔g8? threatened nothing. But his moves had the proper, jarring effect.

Stamina

All great players have an intense will to win. “Not winning a tournament is not an option for me...” Carlsen said in 2011.

But many of his rivals have the same desire. What helps make Magnus different is he combines this with the stamina that allows him to play and play. This makes him reminiscent of another great player.

Bobby Fischer – Bent Larsen

Zürich 1959White to play

Bobby Fischer was often criticized in his teenage years for playing out “obviously drawn” endgames. These were not “book” positions but ones with, for example, equal pawns, all on the kingside, like this.

Mikhail Tal ridiculed Fischer. It was naïve to think experienced grandmasters could be defeated in a position like this, just by prolonging the game, he said. “What’s the matter?” Tal wrote in the tournament book about this position. “ ‘Why is the game not drawn here,’ the reader might rightfully ask.” Fischer played another 42 moves before accepting a draw.

Kasparov described Carlsen as essentially a positional player – “more Karpovian...with Fischerlike intensity.” But Carlsen is Fischer on steroids.

Nigel Short – Carlsen

London 2009White to move

Even Fischer might have accepted a draw. Instead, the game went 69 ♕b5+ ♕d5 70 ♔xa4 ♕xb5+ 71 ♔xb5 draw. “It’s always nice to end with bare kings,” Carlsen said. He also played his last-round game at Wijk aan Zee 2020 until he and Wesley So had just their kings left.

Whether intentional or not, both Fischer and Carlsen followed a premise of the Soviet School: If you keep tension in the position long enough, opponents get nervous and err. This was basic to the thinking of Soviet players when they played abroad. “Western players can play ten good moves. But if the position continues to be unclear they may make one silly move and lose,” as Alexander Khaliman put it.

In addition, if you keep trying to win, opponents may consider a position so hopelessly drawish that they will make needless concessions. A case in point was Carlsen’s game with Nakamura at the 2018 Sinquefield Cup. Their rivalry had become legendary – and lopsided. They had played nearly 120 games by that time and Carlsen had won over and over.

Carlsen – Hikaru Nakamura

Sinquefield Cup 2018Black to move

Carlsen had failed to make inroads for more than 20 moves with queens and rooks on the board. With just rooks on, Nakamura can defend easily, for example, with 62...♔g6 63 g5 ♔h5!.

There are even stalemate tricks such as 62...♖c7 63 g5+ ♔h5! 64 gxf6 ♖f7 65 fxg7 ♖xg7+ 66 ♔h3 ♖g3+!.

But Nakamura chose 62...g5?, granting Carlsen a protected passed h-pawn. Play went 63 h5 ♔g7 64 ♔f2 ♖b7 65 ♖a3 ♔h6 66 ♔e3.

Magnus had made progress but the game should still be drawn as 66...♖d7 67 ♖d3 ♖b7 68 ♔d2 a5 shows (69 ♔c3 a4 70 ♔c4 ♔g7 71 ♖a3 ♖d7! and ...♖d4+ or ...♖d3).

Nakamura made another concession, 66...a5??. He believed he had an impregnable fortress after 67 ♖xa5 ♖b3+ 68 ♔f2 ♖b2+ 69 ♔g3 ♔g7 70 ♖a7+ ♔g8 71 ♖a1 ♔g7 72 ♖f1 ♖a2 73 ♖f2 ♖a3.

But Carlsen has famously said he does not believe in fortresses. First, he freed his king, 74 ♖d2 ♖a7 75 ♔f2 ♔f7 76 ♔e2 ♖b7 77 ♖d3.

Then he sent it on a march on a great circle route: 77...♖a7 78 ♔d2 ♔e6 79 ♔c3 ♔e7 80 ♔c4 ♖c7+ 81 ♔b5 ♖c1 82 ♖b3 ♔f7 83 ♔b6 ♖c2 84 ♔b7 ♖c1 85 ♔b8 ♔g8 86 ♖b6 ♔g7 87 ♖b7+ ♔g8

Finally he broke the c-file barrier at the cost of a pawn, 88 ♖c7! ♖b1+ 89 ♔c8 ♖b3 90 ♔d7! ♖xf3 91 ♔e6 ♖f4 92 h6!.

Nakamura resigned after 92...♔h8 93 ♖b7 ♔g8 94 ♖g7+ ♔h8 95 ♔f7 ♖xe4 96 ♔g6 ♖a4 97 ♖h7+ because he was losing all of his pawns, 97...♔g8 98 ♖e7 ♖a8 99 ♔xf6 and ♔xg5, for example.

Carlsen routinely wins endgame positions that were rated equal by computers. In fact, he has won more positions that were roughly even at move 60 than anyone in history. Again, his experience can help explain it. By 2020 he had played more than 550 games that went beyond move 60, according to databases. Garry Kasparov played fewer than 250 such games in his entire career.

Magnus Myths

His spectacular rise caused Carlsen-watchers to come up with theories to explain him. Early in his career, older GMs said he was simply a cheapo artist. He was a master of the ICC whose lack of depth would be exposed when he faced his elders. “He’s an unusually weak player,” Viktor Korchnoi said. All he does is prompt his opponents to make mistakes: “He knows what will cause them to err!” Korchnoi said. He did not consider that a skill.

Korchnoi eventually changed his opinion. So did Khalifman, a strong grandmaster who won a FIDE knockout world championship in 1999. Khalifman was struck by the lineup of players in the top section of Wijk aan Zee 2007. Thirteen of the 14 players had “schooling,” he said. They followed the proven precepts of the Mikhail Botvinnik method: Study your own games and detect weaknesses. Read the classics of chess literature, like Aron Nimzovich’s My System. Study comes before playing.

The 14th player in the tournament was Magnus. Every day during the tournament Carlsen played dozens of speed games on the Internet. That was bound to show up as superficiality in his moves, said Khalifman. But after examining his “classical” games, Khalifman admitted he was wrong. “Carlsen didn’t read Nimzovich and doesn’t need to,” he said in the August 2008 issue of 64 magazine. “To hell with Nimzovich.”

Quite a different criticism came from other GMs. They said Carlsen is “a child of the computer era.” He was a Fritz clone, programmed by constant study with engines to play the way they do.

This is the greatest Magnus myth. He didn’t even use a database during the first years he took chess seriously. His first coaches were amazed at what he called his “computer incompetence.”

“Honestly, when I was about 11-12 I didn’t even know what ChessBase was,” he told an interviewer from Chesspro.ru. “Back then I simply put a board in front of me, took the books I was studying at the time and looked at everything on that. And the first time I needed a computer for chess was when I started to play on the internet.”

Intuition

It is remarkably difficult to explain how Carlsen chooses the moves he does. Often it seems more whim than algorithm.

Carlsen – Michael Adams

World Cup 2007Nimzo-Indian Defense, Classical Variation (E36)

1 d4 ♘f6 2 c4 e6 3 ♘c3 ♗b4 4 ♕c2 d5 5 a3 ♗xc3+ 6 ♕xc3 dxc4 7 ♕xc4 b6 8 ♗f4 ♗a6 9 ♕xc7 ♕xc7 10 ♗xc7 0-0 11 ♘f3 ♖c8 12 ♗f4 ♘bd7 13 ♘d2 ♖c2 14 ♖b1 ♖ac8

He explained what happened next by saying, “I simply couldn’t resist the urge to put my knight on a1.” Play went 15 ♘b3 ♗c4 16 ♘a1 He went on to win in 77 moves.

Among those who appreciated how un-computer-like Carlsen was is the American grandmaster Sam Shankland: “I saw some statistic that of the top ten players in the world he matches the top choice of the computer the least of all of them.” That is, Carlsen’s rivals are more likely to play the candidate move that machines regard as best.

But computers have also shown us that the difference between the objectively “best” move and the second-best and even the third-best is often slight. What impressed Shankland is that of the same top-ten players, Carlsen is the one most likely to select one of the computer’s three top choices. “Magnus might not play the best move any more often than anyone else,” Shankland said. “But he always plays a good move ...because his natural feel is so great.”

Carlsen – Sergey Karjakin

Wijk aan Zee 2013White to move

Computers look at moves like 29 ♕c2 with the possibility of going to c4.

Carlsen chose 29 ♕h1! with the idea of maximizing his strength on light squares after 30 ♔g1!.

Computers said his idea only made matters worse. Yet White’s position slowly improved and, after a trade of queens following a prepared ♕h3, Carlsen slowly ground down his opponent in 92 moves.

Another myth is that Carlsen is a calculating machine. Yes, he can visualize positions five, ten or more moves into the future. But so can Caruana, Nakamura, Wesley So, Alexander Grischuk, Levon Aronian and several others. One of his prime advantages over them is superior ability to evaluate the end-positions of their mutual calculations. His opponents choose forcing moves in order to reach a position they consider satisfactory for them. But the position is not nearly as good as they thought, as several games in this book can show.

“Play Magnus”

That is the name of the popular software that allows you to play a game with a computerized Carlsen. The different levels are based on his skill and playing style at different ages.

When you take on Magnus-at-5, he asks you, “Can you beat me while I’m busy reading geography books?” His father tried to get him interested in chess at that age but he was more into memorizing the capitals, populations and flags of the world’s countries. His strong suit was curiosity, not obvious intelligence.

“Despite some of the preconceptions about me I wouldn’t say I have a freakishly high IQ. I am just someone who is naturally curious. I like to stretch myself,” he recalled to the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph.

“I was doing jigsaw puzzles before I was two. A year later I started memorizing the names of motor cars. Then it was onto geography. By the time I was five or six, I was studying maps,” he said.

His father Henrik Carlsen, an information technology consultant, is a chess player of about 2100 strength. He tried to interest Carlsen again at age 6, without success. Magnus-at-6 would rather dress up as Pirate Captain Sabertooth than play chess.

At 7 he had moved on to pretending to be Harry Potter. But he felt a bit of sibling rivalry when he saw his father and sister Ellen play chess. “I was lucky,” Carlsen later told Shortlist.com. “I was brainwashed by my parents into believing video games were bad for me. So, because the weather was sufficiently bad and I was sufficiently bored, I started playing my father chess at eight.”

He didn’t beat Ellen, a year older than him, until he was eight and a half and couldn’t defeat his father even at blitz until he was nine. Henrik Carlsen recalled: “I asked him if he wanted to play in the Norwegian under-11 championship the next summer. He agreed and almost every day he studied chess two or three hours.” By then he was reading his father’s chess books, such as Bent Larsen’s Find the Plan and Eduard Gufeld’s The Complete Dragon. He developed the ability to study without a board and pieces. He read books, looked at the diagrams and visualized the moves as he went from page to page. He played in his first tournament at the age of eight years and seven months. He soon had a trainer, Torbjorn Ringdal Hansen. But he appears to be more self-taught than any world-class player in memory. “For as long as I can remember, I have liked to learn things for myself by trial and error, rather than have them drummed into my head by someone else,” Magnus said.

At the end of his life, Vasily Smyslov asked listeners to guess what he considered his greatest achievement. Was it beating Mikhail Botvinnik in a world championship match? Or was it winning two Candidates tournaments? No, he said, it was winning a junior tournament with an 11-0 score. And his most memorable game was one he won when he had been playing for only a few months.

Carlsen’s experience was similar. A year after his introduction to tournament chess, he won the Norwegian under-11 championship with a score of ten wins and two draws. He called it “the single most important tournament win for me... That was a big deal for me.” After a year of taking chess seriously his rating rose 1,000 points, to about 1900 (Hikaru Nakamura’s first posted rating was 684 in January 1995, when he was seven years and two months old. By July 1996 it was 1500).

Henrik Carlsen gave up his job and began to work as a consultant in 2001 to have more flexibility in his work hours. Norway’s best player, Simen Agdestein, took over as Magnus’ trainer. Carlsen found himself playing regularly on the ICC, about 7,000 games from 2001 to 2004, according to Agdestein.

When Magnus was 12 the Carlsens, including his three sisters and his mother Sigrun Carlsen, a chemical engineer, packed into the family’s 1994 Hyundai and took off to travel about Europe. He played 150 tournament games and tied for first in the world under-12 championship. He was awarded the international master title in August 2003.

When he only tied for ninth in the world under-14 championship it seemed like a minor setback. But he was the only international master in the tournament, which included Ian Nepomniachtchi and Maxim Vachier-Lagrave. Within six months he had his first grandmaster norm. He was on his way.

1

Magnus’ Morphy

By the time Carlsen was world champion he had forgotten the way he once played. He discovered this when he tested the app “Play Magnus.”

When Carlsen played against the 12-year-old clone of himself, he concluded the app designers got it wrong. “Magnus 12 is only going for king attacks and he has no technique,” he said. “It’s all tactics. That’s not right. That’s not how I played at that stage.”

But then Carlsen took another look at games he played when he was 12. That was a shock. “I realized it was right,” he said of the app. At 12 he was tactics-focused, just like “Magnus 12.”

This game has his most impressive finish from his early years. He could have played much better, by shifting between queenside pressure and kingside threats. But then we would have never seen his sparkling queen sacrifice.

Carlsen – Hans Harestad

Copenhagen 2003Ruy Lopez, Tchigorin Defense (C98)

1

e4

e5

2

♘f3

♘c6

3

♗b5

a6

4

♗a4

♘f6

5

0-0

b5

6

♗b3

♗e7

7

♖e1

d6

8

c3

0-0

9

h3

♘a5

10

♗c2

c5

11

d4

♕c7

12

♘bd2

♘c6

13

d5!

The knight would be offside after 13...♘a5 14 b3.

13

...

♘d8

14

a4!

Unlike computer-oriented juniors, the young Carlsen read books. And like generations before him he was taught in textbooks how 14...b4? was punished by 15 ♘c4! in a José Capablanca game, 15...a5 16 ♘fxe5 ♗a6 (16...dxe5 17 d6) 17 ♗b3 dxe5 18 d6 ♗xd6 19 ♕xd6!.

14

...

♖a7

Black’s rooks were not connected so 15 axb5 was a threat (15...axb5?? 16 ♖xa8).

Control of the open a-file is enough for a small White plus after 14...♖b8 15 axb5 axb5 16 b4.

15

♘f1

But now we can see why 14...♖a7? was a mistake.

If the d8-knight moves to b7, White can isolate the a-pawn, e.g. 15...♗d7 16 ♗e3 ♘b7 17 axb5 ♗xb5.

That pawn will be a middlegame target after, say, 18 b3 and 19 c4.

Another problem is that on a7 the rook makes a plan of ♗e3 and b2-b4 more desirable, since ...c4?? or ...cxb4?? would hang the rook.

15

...

g6

16

♗h6!

♖e8

17

♘g3

White’s options include doubling rooks on the a-file after ♖a2.

That’s a problem for many mature players – too many good plans.

For example, 17...♕b8 would protect the a7-rook so that he can continue ...♘b7 and meet axb5 with ...axb5.

But White can ignore the queenside and shoot at the king, with 18 ♘h2 and 19 f4!.

Also good is the more aggressive 18 ♕d2 and 19 ♘f5! (19...gxf5?? 20 ♕g5+ and mates).

17

...

♘d7

18

♘h2

f6!

This move frees a square for the d8-knight (19 f4? ♘f7).

But it should have given Magnus a reason to consider h3-h4-h5!.

19

♗e3

♘b6

20

axb5

axb5

21

♗d3

This demonstrates Carlsen’s inexperience. After 21 ♖xa7 ♕xa7 22 h4 he would have stood better on both wings.

But after 21 ♗d3 his queen can be misplaced after 21...♖xa1 22 ♕xa1 ♗d7 and ...♘f7.

21

...

♗d7

22

♕d2

♘f7

23

♖xa7

♕xa7

24

♕e2?

Magnus has delayed h3-h4-h5 so long that Black can make queenside threats. Here 24...c4! 25 ♗c2 ♖a8 is at least equal for Black. Black should play ...c4 on one of the ensuing moves.

24

...

♕a6

25

♘g4

♔g7

26

♗c1

♘a4

It is frustrating to search for an attack that isn’t there – 27 ♕e3 and 28 ♘h6 wouldn’t threaten anything.

Also 27 ♘e3 c4 28 ♗c2 ♘c5 and now 29 ♘ef5+? gxf5 – isn’t close to being a sound sacrifice.

27

♗c2

♖a8

28

♕e3

c4

29

♖f1

♘c5?

Black’s position is solid enough and 29...♕a7 or 29...♗xg4 30 hxg4 ♗d8! and ...♗b6 would give him good winning chances.

30

♘h6

♘g5

Carlsen prepared 31 ♘xf7 ♔xf7 32 f4! with a strong attack.

Black could have defended better with 30...♘xh6 31 ♕xh6+ ♔g8 and ...♗f8.

31

f4!

exf4

At first glance, 31...♔xh6 32 fxg5+ fxg5 looks harmless (33 h4 ♔g7).

But 33 ♖f7! is deadly – 33...♖e8 34 ♖xe7 ♖xe7 35 ♕xg5+.

After 33...♗d8 Carlsen could choose between two wins, 34 h4 and 34 ♕f2!, which threatens 35 ♘f5+ gxf5 36 ♕h4+ and mates.

32

♕xf4

Black intended 32...♔xh6 but now appreciated 33 h4!.

There is no forced win after 33...♖f8! 34 hxg5+ fxg5.

But the absence of the Black queen from the kingside defense means White has the better chances after 35 ♕h4+ ♔g7 36 ♗xg5.

32

...

♗xh3?

33

♕h4!

The trap was transparent (33 gxh3?? ♘xh3+). Magnus is winning now.

33

...

♗d7

34

e5!

It is hard to criticize such a nice combination but he could have won without pyrotechnics.

For example, 34 ♗e3! and 35 ♗d4! creates a threat of ♕xg5 that is surprisingly hard to meet.

Also good is reversing the move order of Magnus’ combination, 34 ♘h5+! and then 34...gxh5 35 e5!, with the game’s finish after 35...dxe5.

Or 34...♔xh6 35 ♘xf6+ ♔g7 36 ♗xg5.

34

...

dxe5

35

♘h5+!

gxh5

The mundane finish is 35...♔h8 36 ♗xg5 fxg5 37 ♕g3 and ♕xe5+ (or 37...♗d6 38 ♕xg5).

Carlsen could have announced mate in three moves.

36

♕xg5+!

fxg5

37

♖f7+

♔xh6

38

♖xh7

mate!

This is the closest we have to a “Morphy finish” by the young Carlsen.

The next time he would finish a game with a truly sparkling queen sacrifice, he got a lot more attention. It was the final game of the 2016 world championship match.

2

Total Board

Carlsen at 12 was not always as one-sided as that game indicates. Early on, he developed a good sense of how to conduct operations on the entire board. After his pressure on the enemy center leads to a static situation in this game, he turns to the queenside. Then he switches to a decisive kingside plan.

Yuri Zimmerman – Carlsen

Schwarzacher Open 2003Grünfeld Defense (D84)

1

d4

♘f6

2

c4

g6

3

♘c3

d5

4

cxd5

♘xd5

Now 5 e4 ♘xc3 6 bxc3 has been played gazillions of times. Black gets more pressure on the d4-pawn with 5...♘b6?! but it isn’t enough to equalize after 6 ♗e3.

5

♗d2

This was a trendy move at the time. White wants to retake with the bishop on c3 after ...♘xc3.

5

...

♗g7

6

e4

♘b6

Carlsen does not oblige him. He will enjoy an extra tempo compared with the 5 e4 ♘b6?! 6 ♗e3 variation but his knight is somewhat misplaced on b6.

Who benefits from these finesses? White, very slightly.

7

♗e3

0-0

8

♗b5

This is a sophisticated idea. White offers Black another extra tempo, after 8 ♗b5 c6 9 ♗e2.

But the tempo is ...c6, which prevents him from playing ...♘c6.

Black needs pressure on the d4-pawn in the Grünfeld, as 8 ♘f3 ♗g4! followed by ...♘c6 shows.

8

...

♗e6

Carlsen opts for a trade of bishops rather than 8...♘c6 9 ♘ge2.

His move fits in with the Hypermodern thinking of Ernst Grünfeld’s defense – to lure White’s center pawns one square further and then exploit them.

Black would stand well now after 9 d5? ♗d7 – or even 9...♗c8 – followed by 10...c6!.

9

♘f3

The tempo-losing battle could continue with 9...♗g4!? 10 ♗e2 ♗xf3! 13 ♗xf3 c5. Black has spent another move on his bishop. But after ...♘c4 he would have a fine game.

9

...

♗c4

This could be tested by 10 ♗xc4 ♘xc4 11 ♕b3 but the Grünfeld-style 11...♘xe3 12 fxe3 c5 13 ♕xb7 ♘d7 should suffice (14 0-0 ♗h6).

10

b3

♗xb5

11

♘xb5

♕d7

12

♘c3

♘c6

13

♕d2

Time is on White’s side. If he can castle and develop his rooks, his advantage in space promises a serious advantage.

Carlsen needs to pressure his center before then. But 13...e5? 14 d5 and ♗c5 isn’t the right way.

13

...

♖ad8

14

♖d1

f5!

This is. Now 15 exf5 ♖xf5 16 0-0 ♘d5 and later …e5 dooms White’s formerly impressive pawn center.

15

e5

It looked risky to weaken e6 with ...f5. But 15 0-0 fxe4 16 ♘xe4 ♕g4! would keep White from exploiting it.

After 17 ♘g3 e5 Black would have equalized.

15

...

♘d5

16

♘xd5

♕xd5

17

0-0

♕b5

Carlsen’s best plan is to double rooks on the d-file and tie White to the defense of his d4-pawn. He is also watching for an opportunity to win it with ...f4.

18

♗h6

♖d5

19

♗xg7?

♔xg7

20

♕c3

h6!

The trade of bishops seemed logical. It rendered ...f4 harmless and might have made the Black kingside vulnerable.

But now endgames (after ...♕b4xc3) would favor Black because the d4-pawn is a chronic target.

A broad pawn center decreases in value as wood is exchanged, as Bobby Fischer reminded us.

21

♖d2

♖fd8

22

♖fd1

♕b4

23

♕e3

e6

Carlsen is ready for a reorganization such as ...♖5d7 and ...♘e7-d5.

White can prevent that with 24 ♖c1 ♖5d7 25 ♖dc2 ♕b6 26 ♖c4.

He might be worse after 26...♘e7 and ...♘d5.

But how would Black make progress after that?

Another plan is 25...♕e7 and ...♘b4-d5, with the added idea of ...g5-g4.

White has an interesting sacrifice, 26 ♖xc6!? bxc6 27 h4 and ♖xc6. Then Black is better but his rooks are strangely ineffective.

24

h4?

♕e7!

25

♕f4

♖h8

His rooks would play very well after 25...♖a5! and 26...♘b4. But Carlsen wants to open a second front and he can do it with ...g5.

26

♕g3

♔f7

27

♕f4

♔e8

Carlsen’s idea is ...♔d7-c8 and ...♕g7/...♖g8. This makes it safe enough for a winning ...g5!.

28

♖c2

♘b4

29

♖c4

♖d7

Not the dangerous 29…♘xa2? 30 ♕d2 b5 31 ♕xa2 bxc4 32 bxc4. By retreating to d7 Carlsen made his rook available for kingside reinforcement at h7 or g7 after ...g5.

30

♕d2

♘d5

31

b4

31

...

g5!

Strategic thinking is over. It is tactics time. Now 32 g3 f4! 33 g4 gxh4 and ...♖g8 is lost.

32

hxg5

hxg5

33

♕xg5

Plugging the h-file with the knight, 33 ♘xg5 f4 34 ♘h3, is doomed by 34...♕h4 and ...♖g7.

For example, 35 ♕d3 ♖g7 36 ♔f1 ♕g4.

Instead, White can set a trap with 34 ♘f3 ♕h7 35 ♔f1 ♖g7 36 ♕c2.

Then 36...♕h1+ 37 ♔e2 ♕xg2 38 ♖g1! turns the tables.

But this is foiled by 36...♘e3+! 37 fxe3 ♕h1+ 38 ♔e2 ♖xg2+.

33

...

♕h7

34

♔f1

♖g7

35

♕c1

35

...

♖xg2!

This is not the only way to win – 35...f4! also does it, as in the last note.

But this is faster (36 ♔xg2? ♕h3+ mates).

36

♔e2

♕g7

White would love to sacrifice on c7 and eliminate that powerful knight.

But even 36...♕h5 37 ♖xc7 ♕g4! 38 ♖c8+ ♔f7 wins.

For example, 39 ♖xh8 ♕e4+ 40 ♔f1 ♕xf3 (41 ♕d2 ♘f4).

37

♖g1

♖h3!

38

♖xg2

♕xg2

39

♘e1

♕e4+

40

♔d2

♘f4

41

♕d1

♖d3+

42

♘xd3

♕xd3+

White resigns

3

Closing Gaps

Young players typically develop their skills unevenly. They may play the opening well but handle endgames horribly. They can calculate forcing variations but can’t tell when an uneventful position is dead even or a White advantage to the tune of +0.50.

There were still major gaps in Carlsen’s skill set in 2003. But he was closing some of them. He was beginning to win games in which he demonstrated both combinational talent and powers of evaluating simple positions. Here is a remarkable sacrifice which is essentially a forcing way to trade queens into a winning endgame.

Carlsen – Christian Laqua

Schwarzacher Open 2003Catalan Opening, Closed Variation (A46)

1

d4

♘f6

2

♘f3

e6

3

g3

d5

4

♗g2

♗e7

5

0-0

0-0

6

c4

c6

The closed variation of the Catalan is far less popular than the open one (6...dxc4). It defers tactics until the early middlegame.

7

b3

The next five moves could be played in different orders, with little difference.

There is no better place for Black’s queenside pieces than ...♗b7, ...♘bd7 and ...♖c8. White’s queen works best on c2 and his rook does well on d1.

7

...

b6

8

♕c2

♗b7

9

♘c3

♘bd7

10

♗b2

♕c7

11

♖ad1

♖ac8

12

e4

This is the first move of the game that could be called forcing. Black should not allow the space-gaining 13 e5!.

12

...

♘xe4

13

♘xe4

dxe4

14

♕xe4

The pawn structure grants White more space. Black lacks support for changing it with ...e5. He aims instead for ...c5.

Back in the 1970s, 14...c5 was the common continuation – until 15 d5! was found to be strong.

For example, after 15...♘f6 16 ♕c2 exd5 17 ♗e5! Black must misplace his queen or allow 17...♗d6 18 ♗xf6 gxf6 19 cxd5 and ♘h4-f5.

If the queen goes to c6, d7 or d8 White can assure himself an advantage with 18 ♘g5!, which threatens mate on h7 after ♗xf6.

Eventually defenders improved Black’s chances with 15...♗f6, instead of 15...♘f6.

Then White would be worse after 16 ♗xf6? ♘xf6.

But the ♗e5 idea of the previous variation was so good that White found he could get a nice game with 16 ♗c1! and ♗f4.

14

...

♖fd8

15

♖fe1

c5

Another version of that maneuver is 15...♗f6 16 ♗c1!, again with a slight edge.

16

d5

♗f6

17

♗c1!

The idea is not just ♗f4 but also ♘g5.

This is very similar to the position that could have arisen after 14...c5 15 d5 ♗f6 16 ♗c1.

In this version each side has added one move – ♖fe1 for White and ...♖fd8 for Black. Which player benefits more?

Black has additional pressure on d5, such as 17...exd5 18 cxd5 b5 and ...♘b6.

However, on d8, the rook would be attacked after 19 ♘g5! ♗xg5? 20 ♗xg5.

Then 20...♖e8? 21 ♕xe8+ and 20...f6? 21 d6 are clearly bad.

Less obvious is 20...♖f8 21 ♕f5!, which threatens 22 d6.

The alternatives to 19...♗xg5 aren’t pleasant either. Black loses after 19...g6? 20 d6!.

For example, 20...♗xe4 21 dxc7.

Also 20...♕c6 21 ♘xf7! so that 21...♔xf7? 22 ♕e6+ and ♗xc6.

Or 21...♕xe4 22 ♗xe4 ♔xf7 23 ♗xb7.

17

...

♕b8

Now 18 ♕g4 exd5 19 ♘g5 is good.

18

♘g5!

It is tempting to play 18 ♗f4 ♕a8 first and then 19 ♘g5 ♗xg5 20 ♗xg5 ♖e8 21 dxe6! ♗xe4 22 ♗xe4.

Since 22...♕b8?? 23 exd7 is lost, Black would play 22...♖xe6 23 ♗xa8 ♖xe1+ 24 ♖xe1 ♖xa8.

There are two differences between 18 ♘g5! and 18 ♗f4 ♕a8 19 ♘g5, as we’ll see.

18

...

♗xg5

19

♗xg5

♖e8

20

♗f4

♕a8

One of those differences is that in this move order, 20...e5 was possible.

But for positional reasons (the passed d5-pawn, the dead b7-bishop) White stands very well.

There is also a tactical trick, 21 ♗h6! with a threat of ♕g4.

For example, 21...♘f6 22 ♕f5 ♕d6 23 ♕g5 and 21...♘f8 22 ♗d2 and ♗c3 is close to lost.

In other words, this move order gives Black an option (20...e5) that was better than what happened in the game – but still bad for him.

Now comes a series of forcing moves beginning with a queen sacrifice. It does not win material but reaches a very favorable rook endgame.

21

dxe6!

♗xe4

22

♗xe4

♖xe6

Black would be a pawn down after 22...♕xe4 23 ♖xe4 ♘f6 24 exf7+ or a piece down after 23...fxe6? 24 ♖xd7.

23

♗xa8

♖xe1+

24

♖xe1

♖xa8

25

♖e7

Let’s scroll back to the note to 18 ♘g5.

If Carlsen had begun with 18 ♗f4 ♕a8 and played the same queen sacrifice, his bishop would now be on g5, not f4.

That would substantially help Black because of 25...♘f8! and 26...♘e6.

With his rook on the seventh rank, White would have a big advantage but not yet a winning one.

25

...

♘f8

But what about 25...♘f6 ? If the bishop were on g5, that would have been met strongly by 26 ♗xf6! gxf6 27 ♖b7.

Instead, the pawn-winning plan Magnus executes in the game would have led to 26 ♖b7 ♘e4 27 ♗b8 ♘c3.

However, he would still be winning because he can make slow progress with ♔g2-f3, while Black’s pieces are passive.

For example, 26 ♔g2 ♔f8 27 ♖c7 ♔e8 28 ♗e5 and ♗xf6 (28...♔d8? 29 ♖xf7).

And did you see the trap in the last variation?

After 27 ♖b7 ♔e8 28 ♗e5 Black could play 28...♘d7 because 29 ♗xg7? ♔d8 and 30...♔c8 will trap the rook.

26

♖b7!

♘e6

27

♗b8!

♘d8

28

♖e7

The threat of ♖e8 mate gains time to win the a7-pawn. Black finds a forcing way to make it a rook ending.

28

...

♘e6

29

♗xa7

♔f8!

Now 30 ♖d7? allows him to force a draw, 30...♔e8 31 ♖b7 ♘d8! (32 ♖c7 ♘e6 33 ♖b7 ♘d8).

30

♖b7!

♘d8

31

♖b8

♖xa7

32

♖xd8+

♔e7

33

♖d2

♔e6

When one player has an extra queenside pawn in a rook ending and each side has three kingside pawns, the outcome often depends on who can attack the kingside pawns.

Black could pose more problems with 33...g5, which discourages White’s plan of h2-h4 and g2-g3.

After 34 ♔g2 f5 35 ♔f3 ♖a3 he would also stop a2-a4 and tie White’s rook to the defense of the a2-pawn.

That shouldn’t be enough to draw but White would need to figure out another way to win, perhaps after 36 h4 h6 37 h5 or 37 hxg5 hxg5 38 g4.

34

♔g2

h5

35

h4

g6

Both players safeguarded their kingside. Only the pawns at f2 and f7 are not protected by a fellow pawn.

But Carlsen’s rook is much more active than Black’s and he can win with routine moves, such as a2-a4, ♔f3 and ♖d5.

Therefore Black has to generate counterplay. Better practical chances were to be offered by 35...f6 36 ♔f3 g5 and 37 ♔e4 gxh4 38 gxh4 ♖g7 (39 f3 ♖g1).

36

♔f3

♔e5

37

a4!

♖c7

38

♖d5+

♔e6

39

♔f4

The king is headed to g5.

Black can stop that with 39...f6 but then the g6-pawn will be vulnerable after 40 ♖d8.

Black soon runs out of moves, e.g. 40...♔e7 41 ♖g8 ♔f7 42 ♖b8 ♖c6 43 ♖b7+ ♔e6 44 ♖g7 or 43...♔f8 44 ♔e4.

Similar is 40...♖c6 41 ♔e4 ♖c7 42 ♖e8+ ♔f7 43 ♖b8 ♖c6 44 ♔d5 ♖e6 45 ♖b7+.

39

...

♖c8

40

♔g5

♖a8

41

f4!

This threatens 42 ♖e5+ ♔d6 43 ♔f6.

There was a good alternative plan of 41 f3 and 42 g4 so that 42...hxg4 43 fxg4 and 44 h5 creates a passed pawn.

For example, 41...♖c8 42 g4 ♖h8 43 ♖d1 should win but progress is slower after 43...♔e7 44 ♖e1+ ♔f8.

41

...

f6+

42

♔h6

This is a mature move. White would still win after 42 ♔xg6 ♖g8+! 43 ♔xh5 ♖