13,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

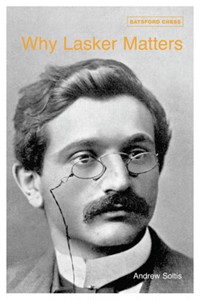

Emanuel Lasker was the longest-reigning world champion (1894-1921) and remained one of the world's top 10 players for nearly four decades. He competed against top players such as Capablanca, Rubinstein and Alekhine at the height of their game, and was consistently successful, yet almost no one studies his games today. Lasker is often overlooked by the modern chess player, and the secrets of his success remain a mystery. Chess journalist Andy Soltis reveals for the first time the winning formula behind Lasker's phenonemal achievements. With over 100 annotated games, Soltis analyses the tricks, traps and techniques behind the winning moves, and makes Lasker's methods accessible to today's players.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 791

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Why Lasker Matters

Andrew Soltis

BATSFORD

Introduction

“The greatest of the champions was, of course, Emanuel Lasker.” – Mikhail Tal

“Emanuel Lasker ... was a coffeehouse player.” – Bobby Fischer

“The idea of chess art is unthinkable without Emanuel Lasker.” – Alexander Alekhine

“I admired him ... until I studied his games.” – Bent Larsen

“My chess hero.” – Viktor Korchnoi

“The quality of (19th century games) games ... they are horrible. Even Steinitz-Zukertort, Steinitz-Lasker (groans). – Garry Kasparov

Emanuel Lasker is a controversy. But he’s also a mystery: How could someone who played so many profound and yet so many second-best moves have become world champion? And how could someone who played so many dull and also so many sparkling games – in short, so much bad chess as well as great chess – have remained champion for a record 27 years?

The answer that comes to the minds of many young players is that some stars of Lasker’s era would be, well, no better than mere masters today. There’s some evidence to support this. The level of play, particularly in defense, was poor when Lasker began to play, and endgame technique was uneven, to say the least. But Lasker’s opponents included Alexander Alekhine, Mikhail Botvinnik, Max Euwe, Jose Capablanca, Akiba Rubinstein, Yefim Bogolyubov, Richard Reti, Frank Marshall and Siegbert Tarrasch. They were much more than mere masters, to say the least. And his total record against the group is a big plus score.

Another explanation is that Lasker remained at the top for so long simply because he played so rarely. There is evidence for this, too. Lasker often went years between tournaments and world championship matches. But whenever he returned he was surprisingly active and surprisingly strong. Garry Kasparov once declared that he had “won the world championship title three times in three years, a record for chess history!” In fact, he didn’t. No one has ever won three championship matches in three years. But the closest was Lasker, who did it in four years.

Lasker’s contemporaries had their own explanations for his remarkable accomplishments: He beat Wilhelm Steinitz in their first match because he didn’t blunder and because he wasn’t 58 years old, they said. But that hardly explains how Lasker went on to amass a tournament record over the next 35 years that Reti said “must be considered the most successful of all chess masters.”

Tarrasch gave three answers to the Lasker riddle. Early in Lasker’s career Tarrasch presented the case that his fellow German was simply lucky. In his tournament book for Nuremberg 1896, he itemized examples of Lasker’s good fortune in a “luck scoretable” that explained why Lasker finished at the top of the real scoretable. Later Tarrasch had another explanation. He “circulated the legend that Lasker had a simple plan of play: trade off all the heavy pieces and go into the endgame,” Aron Nimzovich said. Still later, Tarrasch came up with a third answer: Lasker hypnotized his opponents. Only that can explain how the world’s best players made bad moves against him that they would never consider against anyone else, he said.

And then there was Euwe, who said there was simply no way to imitate Lasker. “It is not possible to learn much from him,” Euwe wrote, “One can only stand and wonder.” That view – that someone could play chess so powerfully and yet inexplicably – was exactly the kind of fuzzy thinking that would have outraged Lasker.

THE PSYCH HOAX

Long before Lasker, there were masters who made their decisions in the most practical way: They tried to find the moves that had the greatest chance of success, regardless of whether they were “correct.” After Adolf Anderssen lost three straight games in his match with Paul Morphy he abandoned 1 e4, in favor of 1 a3?!. Another of Morphy’s opponents met his 1 e4 with 1...f6? to avoid the American’s huge book knowledge. (It worked—he won.) Morphy himself switched strategies after he got off to relatively poor starts in his matches with Louis Paulsen and Daniel Harrwitz. Capablanca suggested that a player could take the practical approach even if he didn’t know his opponent. When Capa adopted a dubious Ruy Lopez line in a 1914 clock simultaneous he explained, “This defense is not good but I used it in the conviction that my opponent would not know what to play.”

But the pragmatic attitude was discredited by Wilhelm Steinitz. He said Morphy used his great “intuitive knowledge of human nature” to “play the man rather than the board.” Morphy’s quaint approach could now be retired, Steinitz added. In his era, science had great cache and Steinitz claimed to have applied the scientific method to formulate eternal rules. Anyone could apply these rules against an opponent. Only the board mattered. “My opponent might as well be an abstraction or an automaton,” Steinitz wrote.

It is well nigh impossible to underestimate the influence that Steinitz (and his disciple Tarrasch) had on chess thinking during their era. As a result when Lasker arrived on the scene – and successfully violated the Steinitz/Tarrasch rules – his success was a mystery. What could explain it?

Reti thought he figured it out when he read an interview Lasker gave to the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf after his victory at New York 1924. Lasker said that some of his opponents have recognizable quirks, such as Geza Maroczy who was better at defense than attack. Reti concluded that Lasker “is not so much interested in making the objectively best move as he is in making those most disagreeable to his opponent.” In other words, Lasker played the man.

But then Reti went completely off the rails: Lasker often accomplishes this, he wrote, “by means of intentionally bad moves.” This is nonsense.

If this were true, Lasker would not have been just a 2500-player as some of today’s players believe. Or a 2700-plus-player as retroactive ratings suggest. If Lasker could deliberately play badly against the world’s best players – and regularly beat them – he would have been over 3000.

The primary evidence cited by Reti and his successors in advancing the psychology hoax are:

–Lasker played obviously bad opening moves – such as g2-g4 in the Dragon Sicilian.

–He gave up material for something hard to define, something called “positional compensation.”

–He often played the “practical” move rather than try to find the best move, and

–He counterattacked and complicated even before his position was clearly bad.

Today’s players should look at this and laugh. In a typical Sicilian Defense nowadays you might see g2-g4 by White, a Black counterattack by move 10, a positional sack by either player and “practical” moves by both. No one would consider the moves deliberately bad or the slightest bit “psychological.”

Nevertheless, Reti offered a simple way of explaining the inexplicable – and Lasker was the perfect subject since his moves were often so original they defied any other explanation.

Lasker – Levenfish Moscow 1936

White to play

White’s center is collapsing. His chances of survival seem slim after 27 cxb4 ♘xd4 or 27 ♗xc6 ♗xc6 28 cxb4 ♕xd4+. Some computers recommend retreat (27 ♕f2) although that would likely lose without a fight (27...bxc3 28 ♗xc3 ♘xe5 29 fxe5 ♗xe5).

Lasker played 27♖e3! so that he could attack with ♕h4 and ♖h3. It’s a good try in a bad position. But even if everything worked out, all that White threatens is a check on h7.

Yet Black called it “one of those moves which time and again have given Lasker the chance to save himself in a difficult position. When his strategic plan proves to be refuted, Lasker boldly and skillfully creates tactical complications and nearly always comes out of them the victor.”

That was the case here: 27...bxc3 28 ♗xc3 ♘xe5 29 fxe5 ♗xe5 30 ♕h4 ♖xc3? 31 ♖xc3 ♗xd4+ 32 ♔h1 ♗a4 (32...♗xc3 33 ♕d8+!) 33 ♖dd3 ♗b5 34 ♗xg6! fxg6 35 ♖h3 ♕d7 36 ♖cg3 ♗d3? 37 ♖xd3 Resigns.

Today we would say White complicated because he had to. But in Lasker’s day 27 ♖e3 was considered his special brand of sorcery. And Reti revealed the magician’s trick: His moves were part of elaborate mind games. In the 1920s “psychology” was a buzzword, just as “science” had been a few decades before, and so the mind-game explanation came into vogue. Nimzovich, for example, used “psychology” and “psychologically” nine times in his slim volume on Carlsbad 1929 to explain moves.

The hoax that Reti “foisted on the world” – to use Gerald Abrahams words – allowed annotators to become arm-chair Freuds. If you couldn’t explain a move, there was a simple answer. Psychology! In Game 81 Maroczy adopted a variation of the French Defense as White that Maroczy himself had discredited as Black years before. No one could explain why he did this. The possibility that the world’s leading authority on the French could have found improvements for White was ignored. No, the annotators concluded that Maroczy had a death wish, a “suicide mood,” as one put it, and that Lasker had encouraged it in some mysterious but diabolical way.

Even a move that was objectively best – but looked strange – would be rationalized in shrink terminology:

Ilyn-Genevsky – Lasker Moscow 1925

White to play

In this position from Game 87 White played 13 ♘ce2, which was given an exclamation point in the tournament book. (It deserves “?!” at best.) Lasker sacrificed his queen with 13...♕xa2 14 ♖a1 ♕xb2 15 ♖fb1 ♕xb1+ and Black obtained a rook, bishop and pawn as compensation. But he didn’t get a mating attack or even the initiative as a result. The conclusion then and one that is still being circulated is that “13...♕xa2?!” was pure psychology. “It probably wouldn’t occur to any modern master to sacrifice the queen in such a position,” wrote Yefim Bogolyubov.

And that’s been the unfortunate Reti legacy – a tendency to exaggerate the role of psychology in the moves of Lasker (or anyone else). In fact, 13...♕xa2! was simply the best move in the position. True, it was also a good move to play against such an inexperienced opponent. Lasker did play the man. But he didn’t play the fool.

LASKER ON LASKER

The one person who could unravel the mystery of Emanuel Lasker was Emanuel Lasker. But unlike Steinitz and others of this era, who kept few secrets, Lasker said fairly little about his chess instincts and often seemed to be trying to mislead his opponents. He regularly took calculated risks yet claimed that taking chances in chess “is nearly as difficult as to take chances, say, in geometry.” He reveled in complications but insisted the simpler of two equal moves was always better.

His critics ignored the contradictions. Reti cited the De Telegraaf interview to show how Lasker studied his opponent’s games. But he also attributed his success to “healthy common sense.” To illustrate this he told a story: After one of his matches, Lasker lectured at the Vienna Chess Club. A member of the audience asked whether the reason he chose certain openings was that his opponent had declared those lines to be unsatisfactory and Lasker had found flaws in the analysis. Lasker denied this. He chose the openings because they were grounded in solid, general principles, he said. “I did not study anything.”

So which was it? Lasker the clinical researcher who deeply scrutinized his opponents’ every move? Or Lasker who didn’t study anything? Reti accepted both notions and Lasker didn’t disabuse him of them. In one of his last articles Lasker had this to say:

“About my style very much has been written, comprehensible and incomprehensible, deep and superficial, praise and criticism. And after being silent on this question for a long time, I wish to speak about it myself.” He then went on, in the Soviet yearbook of chess for 1932-35, to say his talent “lies in the sphere of combinations”(!). Considering how rarely he combined, this must be one of his final jokes upon the chess world.

Lasker was more candid in an interview he gave nearly 40 years before, to the Berliner Schachzeitung in 1896, which can serve as a brief autobiographical introduction. Lasker, a brilliant, diligent student with an aptitude for mathematics, began to play chess seriously at 16. He followed his brother Berthold to Berlin’s chess cafes and a favorite tea parlor where he became a regular until he had to pursue his education elsewhere. “At 17 I went for two and a half years to a provincial town where I won a match of five games from the strongest local player – my mathematics teacher. Besides him there were only checker players there,” he said. When he returned to Berlin he began to frequent the Café Kaiserhof but found that many of the Berliners – “and unfortunately Mr. Horatio Caro was among them” – considered it harmful to play such a weak opponent.

I’m going to interrupt the narrative here to ask a question. The Lasker of the history books, the one he presented to the world, went from ♕-odds player at 16 to garden-variety amateur at 19 – to international star at 21. How did he manage this last Leko-like leap if he was a devoted student?

The answer is he wasn’t that student. By all accounts Lasker was two years ahead of pupils his age before he took up chess but later graduated “on time” or perhaps a year behind. Instead, he seemed to have become a fulltime café player, perhaps the youngest professional in the world. It was in the cafes and that teahouse, where he met his blood-rival Tarrasch, that Lasker learned chess. Most of all, he learned to sit on his hands. He acquired legendary patience, which paid off when he avoided bad moves that would have cost him games – and the lunch money he had wagered on their outcome. As a result Lasker blundered less often than any world champion.

End of interruption, Back to the official story.

Lasker’s sudden rise began as he turned 20. The Café Kaiserhof organized a tournament. Every player paid a thaler to enter and the winner collected the entire amount. Lasker won every game. He was convinced by an admirer to enter the biennial German Chess Congress, which would be held in Breslau in 1889. These events were hugely important at the time. Foreign players entered them in order to earn the master title, and masters entered them to gain international renown. Lasker was placed in one of the three “Hauptturnier” sections, or minor tournaments, “and to my surprise won first prize! So began my chess career.”

And so begins the Lasker mystery. How did he do what he did? No one has provided a satisfactory answer. Yet the clues are there, waiting for us, in the games.

The Games

1

What? Where is Lasker-Bauer? You know, the 2 bishop-sacrifice. Almost every collection of Lasker games begins with that, doesn’t it?

Yes, but we’re going to start earlier, with other games, because the Bauer crush is quite out of character for Lasker. He lost more brilliancy prize games than he won and his sacrifices rarely had to do with mating attacks.

What was truly typical of Lasker is that he relied on tactics, not combinations. There’s a difference. He pursued his goals with the help of tactics, often just two or three moves deep, in much the same manner as Sammy Reshevsky, Anatoly Karpov and Peter Leko.

Most of all Lasker wanted to win games with a logical, rational plan, as Steinitz so often did. Here’s a representative example of a Lasker plan working.

Tietz – Lasker German Chess Congress, Hauptturnier A, Breslau 1889Ruy Lopez (C79)

1

e4

e5

2

♘f3

♘c6

3

♗b5

a6

4

♗a4

♘f6

5

0-0

d6

This is sometimes called the Steinitz Defense, Doubly Deferred. Among its points is that 6 d4 allows 6...b5! 7 ♗b3 ♘xd4 8 ♘xd4 exd4 and then 9 ♕xd4? c5, the trap as “old as Noah’s Ark.” (But when you check databases you’ll find one example of 5...d6 before this game.)

6

d3

♗e7

7

h3

0-0

8

♗xc6

White’s sixth move was suspicious, his seventh cowardly and this one looks just wrong. What was he thinking? Before we give up on the game here and skip ahead to Lasker-Lipke, let’s try to figure these moves out.

The basic idea comes from Adolf Anderssen, who was the world’s top active player when he introduced it in slightly different form. Anderssen worked out an attacking plan with g2-g4 and ♘e2-g3. To limit Black counterplay and keep the center somewhat closed, he felt White needed ♗xc6.

8

...

bxc6

9

♘c3

c5!

A fine idea of Louis Paulsen, the first great defensive player. Black prepares the maneuver ...♘d7-b8!-c6-d4 and the attack on the center with ...♗b7/...c4.

10

♘e2

♘e8

The young Lasker tried to emulate Steinitz. But he kept finding himself in situations in which Steinitz’s principles conflicted with one another. One principle suggested the player with the two bishops should give them scope (10...c4 11 ♗e3 cxd3 12 ♕xd3 ♖b8). But Steinitz also said a player should not open the position until he finishes development.

11

g4?!

White continues the Anderssen plan and stops the freeing ...f5. He can continue to build up via ♘g3, ♗e3 and ♕d2 while keeping the center closed (c2-c4). Once he’s ready he can open matters with ♘h2 and f2-f4 or just keep building (♔h2, ♖g1-g3/♖ag1/♘f5).

11

...

h5!!

Of course. After 12 gxh5 ♗xh3 13 ♖e1 f5 Black exploits the exposed kingside. So why the double exclam? Wasn’t the idea of ...h5 routine, predictable – totally obvious?

The answer is: Not in 1889. Compare this with the problem that King’s Indian players wrestled with more than 70 years later when they tried to find a solution to the Saemisch Variation (1 d4 ♘f6 2 c4 g6 3 ♘c3 ♗g7 4 e4 d6 5 f3 0-0 6 ♗e3). A main line was 6...e5 7 d5 c6 8 ♕d2 cxd5 9 cxd5 a6 10 g4 ♘bd7 11 ♘ge2.

White’s edge becomes manifest if he can play ♘g3 and h2-h4-h5. But Svetozar Gligoric introduced a daring idea, 11...h5!, in 1958. The conventional wisdom said that once Black castles kingside, the only open lines he wants there come from ...f5. But that had repeatedly failed. Instead, Gligoric said, Black should challenge g4 head on. He obtained good play after 12 h3 ♘h7 (13 gxh5 ♕h4+ or 13 0-0-0 h4 followed by ...♗f6-g5).

12

♘h2

A natural positional plan is 12...hxg4 13 hxg4 ♗g5. But Black is not eager to dissolve the h3 target. Instead, his plan is ...g6/...f5/...♘f6.

12

...

♗h4

13

♗e3?!

g6

14

♔g2

f5!

Now 15 gxh5? f4! would decide the game strategically. That’s the kind of game Lasker wanted to play. With the g-file opened and h3 exposed, Black should win with simple moves (16 ♗d2 ♕g5+ 17 ♔h1 ♗xh3 18 ♖g1 ♕xh5).

15

f3

White loses the game during moves 13-16. Opening a file with 15 gxf5 gxf5 16 exf5 ♗xf5 17 ♘g3 ♕d7 18 ♘xf5 ♕xf5 is dubious. But he can put up a good fight for the kingside with 15 f4 ♗b7 16 gxf5 and 17 ♘c3.

15

...

♘f6

16

gxf5?

After f2-f3 White had to leave his pawns where they are – not this or 16 g5? ♘h7. Black certainly has the better chances following 16 ♘g1 ♖f7 17 ♕e2 but there’s still a lot of game left.

16

...

gxf5

17

♗f2

♘h7

18

♕e1

After 18 ♗xh4 ♕xh4 19 ♘g1 Black can win a pawn with ...fxe4 and ...♘g5 or play for more with 19...♔h8, e.g. 20 ♕e1 ♖g8+ 21 ♔h1 ♖g3.

Another conflict in basic principles. Should Black trade his bad bishop? Or should he avoid exchanges because they ease White’s restriction?

18

...

♗e7!

It’s the restriction that makes the plan work. White has no adequate defense to ...f4 followed by the doubling of Black pieces on the g-file and the c8-h3 diagonal.

19

h4

♔h8

20

♔h1

f4!

21

♖g1

♕e8

Black could also win the h-pawn with ...♗f6, ...♕e7, ...♖g8 and ...♘f8-g6.

22

♕f1

♗e6

23

♗e1

♕f7

24

♖d1

This will enable White to swap all rooks on the g-file.

24

...

♖g8

25

♖d2

♖g6

Tarrasch believed there was only one right move in any position. “Each position must be regarded as a problem where it is a question of finding the correct move, almost always only one, demanded by that position. In a game of chess secondary solutions are almost non-existent,” he wrote.”

Lasker disagreed. When a position is strategically won, there is likely to be a secondary solution, and here it was winning the h-pawn with 25...♘f8 and ...♘g6 (26 ♖xg8+ ♕xg8 27 ♗f2 ♘g6 28 ♕e1 ♕d8).

26

♖xg6

♕xg6

27

♘g1

♖g8

Now on 28 b3 Black would revert to the pawn-winning plan of ...♘f8/...♕g7/... ♘g6. White’s choice makes it even easier

28

♖g2?

♕xg2+

29

♕xg2

♖xg2

30

♔xg2

♗xa2!

31

♘e2

♗b1!

White resigned after: 32 ♘c1 ♗xc2 33 b3 ♘f8 34 ♔f1 ♘e6 35 ♗f2 a5 36 ♔e2 a4 37 bxa4 ♗xa4 38 ♘a2 ♘f8 39 ♘c3 ♗d7 40 ♘d5 ♗d8

2

Every world champion is, to some degree, a critic of his predecessor. Kramnik found faults in Kasparov just as Kasparov did with Karpov and so on. Lasker’s critique of Steinitz was below the surface. He went to extraordinary lengths to praise him in words. But his moves showed how he had found flaws in Steinitz’s thinking. Steinitz emphasized positional strengths and weaknesses. Lasker thought in terms of targets, that is unprotected or inadequately protected enemy material that could be assaulted, like the h-pawn through most of the last game. Here’s another illustration.

Lasker – Lipke German Chess Congress, Hauptturnier A, Breslau 1889Vienna Game, Paulsen Variation (C26)

1

e4

e5

2

♘c3

♘f6

3

g3

This system came briefly into fashion when Paulsen adopted it in the 1870s.

3

...

♗c5

But it went out of vogue after the turn of the 20th century, in part because of 3...d5 4 exd5 ♘xd5. One Lasker biography claimed 5 ♗g2 ♗e6 favors Black. That view wasn’t overthrown until Smyslov-Polugaveysky, 1961 Soviet Championship: 6 ♘f3 ♘c6 7 0-0 ♗e7 8 ♖e1 ♗f6 9 ♘e4 0-0 10 d3 ♗e7 11 a3 ♘b6 12 b4 and ♘c5 with advantage. Smyslov played the Vienna for the first time in his life and said he had been inspired by Lasker.

4

♗g2

0-0

5

♘ge2

d6

6

0-0

♘c6

7

d3

♗e6

A standard White option, which he had at moves 6-8, is ♘a4 and ♘x♗. But he has another use for the knight, stopping 8...d5!.

8

♘d5!

Paulsen originated the ♘d5 idea when ...♗xd5/exd5 is a fork. Lasker-Popiel, Berlin 1889 went 7 h3 ♗e6 8 ♘d5 and 8...♗xd5 9 exd5 ♘e7 10 c4 ♕d7 11 d4.

8

...

♗xd5

White was intending 9 ♗g5 as well as 9 c3/10 d4, winning a piece.

9

exd5

♘e7

If Black threatens the d-pawn the other way, 9...♘b4, then 10 ♗g5?! is answered by 10...h6. But on b4 the knight cannot get back to exploit the d4-hole and Black would be worse after 10 c4! and 11 a3.

10

♗g5

Modem masters are always looking for a positional pawn-sacrifice and here the candidate is 10 d4 exd4 11 ♘xd4. But White’s compensation is thin after 11...♘exd5 12 c4 ♗xd4 13 ♕xd4 ♘b4 or 12 ♘b3 c6 13 ♘xc5 dxc5.

10

...

♘d7

White doesn’t expect big advantages in the 3 g3 Vienna. One of the small ones he might enjoy is 10...♘f5 11 ♘c3 h6 12 ♗xf6 and then 12...♕xf6 13 ♘e4 ♕e7 14 ♘xc5 dxc5 15 c3.

11

d4

exd4

This was the first Lasker game that attracted annotators, and virtually all of them cited 11...♗b6 12 dxe5 dxe5 as an alternative. They continued that analysis with 13 d6! cxd6 14 ♕xd6 ♖e8 15 ♖ad1 ♘f8 16 ♕xd8 ♖axd8 17 ♖xd8 ♖xd8 18 ♗xe7 and wins. But 12...♘xe5! is obviously superior and nearly equal.

12

♘xd4

h6!

13

♗e3

♘e5?!

There are usually two general policies for Black in such positions. He can maximize piece play or he can trade enough pieces so that White’s space edge is not significant. The text adopts the first policy but the second one, 13...♘f6 14 c4 ♕d7 and then 15 ♕-moves ♘g4!, was better. White can try 15 h3 ♘f5 16 ♘xf5 ♕xf5 17 ♗xc5 dxc5 instead. But Black, with ...♘e4-d6 in mind, is equal.

14

♕e2

♕d7

15

h3

Now on 15...♘f5 16 ♘xf5 ♕xf5 17 ♗xc5 dxc5 White’s bishop is not as bad as in the last note (no c2-c4) and he can use his extra tempo to play 18 ♖fel with advantage.

15

...

♖ae8

16

♖ae1!

Steinitz’s principles held that White’s strengths – his bishops and space edge – should guarantee him an advantage. He can marshall his strengths with f2-f4 and g3-g4, and try to overwhelm Black with f4-f5-f6. But this requires considerable care. After 16 f4 ♘5g6 17 ♕f2 Black can simplify nicely with 17...♗xd4! 18 ♗xd4 ♘f5 (19 ♗c3 ♘e3).

16

...

a6

Lasker was more concerned with specific targets. He can see targets at g7 and h6 but he knows that he created a target for Black by leaving his a-pawn unprotected. To play 16 ♖ae1 he had to assure himself that 16...♕a4 would not be strong.

Black apparently agreed, seeing ♕-traps after 17 b3!, e.g. 17...♕xa2?? 18 ♖a1 ♕b2 19 ♖fb1 ♕c3 20 ♘b5 ♕b4 21 ♖a4 or 17...♕b4? 18 c3 ♕xc3 19 ♘b5 ♕b4? 20 ♗d2.

Better is 17...♕a5 18 ♕b5 ♕c3 or 18...♕xa2 but Black is still a bit south of equality.

17

f4

♘5g6

18

♕f2

The threat is 19 f5 and 20 f6. And 18...f5?? 19 ♘e6 would have sent Steinitz into apoplexy.

18

...

♗xd4

The kingside is the more vulnerable target: 18...♕a4 19 b3 ♕xa2 20 f5 ♘e5 21 f6 ♘7g6 22 fxg7 ♔xg7 23 ♘f5+ followed by ♗xc5 and ♕d2xh6+ wins.

19

♗xd4

♘f5

20

♗c3

White will try to expose g7 with 21 g4.

20

...

♖xe1

There have been relatively few forcing moves to consider so far. But 20...h5, with the idea of 21...h4 22 g4? ♘g3, would force both sides to calculate 21 g4 hxg4 22 hxg4.

Then 22...♘fe7 allows a strong 23 f5! and 22...♘fh4 similarly fails to 23 ♖xe8 ♖xe8 24 f5 ♘xg2 25 fxg6!. That leaves 22...♘h6 but after 23 g5! ♘f5 24 ♗e4 White’s position is growing stronger.

20

...

♖xe1

21

♖xe1

♖e8

Once all the rooks are gone Black can counterattack with ... ♕a4!.

22

♗f3

To play 22 ♗e4!, which threatens 23 g4 and 24 f5, you have to see that 22...h5 is met strongly by 23 ♕f3 h4 24 ♕g4!. White apparently didn’t.

22

...

♖xe1+

23

♕xe1

The minor piece ending, 23...♕e7 24 ♕xe7 ♘fxe7, leaves Black with no compensation for the two bishops.

23

...

♘fe7

Soviet teacher Vladimir Zak, whose students included Boris Spassky and Viktor Korchnoi, was a Lasker fan. In his book on Lasker, Zak investigated the ♕-raid at various points and pointed out that 23...♕a4 24 h4! is strong (24...♕xc2? 25 ♗e4 or 24...♕xa2? 25 h5 and 26 g4). The text, which threatens ...♕xh3, is an attempt to improve the idea.

Since ...♕a4 always allows White’s queen a free hand on the e-file and d4-g7 diagonal, the more solid alternative is 23...♕b5 and ...♕c5+. White’s bishops keep his edge after 24 ♔g2 ♕c5 25 ♗e4 but progress is unclear.

24

♔g2

♕a4

25

♕d2

♕xa2

26

♕d4

f6!

The knights have to avoid situations in which they alone defend one another (26...♘f5? 27 ♕e4 ♘ge7 28 ♗g4 g6 29 ♗xf5).

27

♕e4!

♕b1?

On a2 the queen prevented the f3-bishop from moving (... ♕xd5). White would have to show what he had after 27...♔f8! 28 h4 a5. Black’s queen can become active later. For instance, 29 ♔h3 b5 30 ♗h5 looks good – 30...♘h8 31 ♕h7 ♘f7 32 ♗xf6.

But 30...b4 32 ♗d4 ♕b1! is tough to crack (33 ♗xg6 ♘xg6 34 ♕xg6 ♕h1+ 35 ♔g4 ♕d1+ and ...♕xd4 with a winning ending).

28

h4!

♔f8

29

♗h5

Now 29...♘h8 30 ♕h7 ♘f7 again loses to 31 ♗xf6! (31...♘f5 32 ♕xf5 gxf6 33 ♕g6).

29

...

f5

30

♕d4

Not 30 ♕e6? ♕xc2+ 31 ♔h3 ♕e4. White might have tried 30 ♕d3, which threatens to win a piece (31 ♗xg6 ♘xg6 32 ♕xf5+). That makes 30...♔g8 31 ♕d4! much stronger because ♕xg7 is more than a check.

The crucial defense is 30...♔f7. Then White can transpose into the game with 31 ♕d4 ♕xc2+ 32 ♔h3 ♕e4. Or he can try 31 g4!? when 31...♔g8 allows him to win a piece with 32 ♗xg6 ♘xg6 33 ♕d4. But 33...♘xf4+ 34 ♕xf4 ♕xc2+ looks like a perpetual check.

30

...

♕xc2+

Isaac Linder, the Russian historian, said this game was one of the first examples of a player sacrificing two queenside pawns for a kingside attack.

31

♔h3

♕e4!

The threat of ...♕h1 mate forces White to rely on checks.

32

♕xg7+

♔e8

33

♗xg6+

Now 33...♘xg6 34 ♕xg6+ ♔d7 35 ♕f7+ ♔c8 36 ♕e6+ wins.

33

...

♔d7

Threatening perpetual check (34 ♔h2 ♕e2+ 35 ♔g1 ♕e3+ 36 ♔f1 ♕f3+).

34

♗xf5+!

♕xf5+

35

♕g4!

White’s kingside pawns are very fast (35...h5 36 ♕xf5+ ♘xf5 37 g4! hxg4+ 38 ♔xg4 or 35...♔e8 36 ♕xf5 ♘xf5 37 ♔g4 ♘e3+ 38 ♔h5 ♘xd5 39 ♗d2 as in the game).

35

...

♕xg4+

36

♔xg4

♘xd5

Another fundamental difference is that Tarrasch believed “a good game of chess is decided in the middlegame.” That seemed to be true in an earlier era, when defense was so hideous. But Lasker encountered situations like this, in which a good defender has been outplayed but can reach an endgame with survival chances. Black has potential passed queenside pawns, a centralized knight and an agile king.

37

♗d2!

This keeps the knight at bay (compared with 37 ♗g7 ♘e3+ 38 ♔h5 ♘f5 or 37 ♔h5?? ♘xc3 38 bxc3 a5).

37

...

♘f6+

Black’s king can’t stop the pawns by itself (37...♔e7 38 ♔f5 ♔f7 39 g4). His choice was between bringing the knight back or starting a pawn-race with 37...c5.

But White has the right queenside pawn to slow down Black’s majority. For example, 38 ♔f5 c4 39 ♔g6 b5 40 ♔xh6 b4 looks dangerous but White prevails after 41 ♗c1 c3 42 h5.

38

♔f5

♔e7

39

g4?

White has to keep the Black knight and king from key kingside squares. He wins after 39 ♔g6 ♘e4 40 ♗e3! (40...♘xg3 41 f5).

39

...

d5?

Black misses his opportunity, 39...♔f7 40 g5 ♘g8! (not 40...hxg5 41 fxg5 ♘g8 42 g6+ and 43 h5, e.g. 42...♔g7 43 h5 ♘e7+ 44 ♔g5 ♘g8 45 ♗c3+).

After 40...♘g8 White is stopped by 41 g6+? ♔e7 because his h-pawn isn’t passed. Better is 41 h5 but Black has useful moves like 41...c5 and 41...b6.

40

g5

hxg5

41

fxg5

♘d7

Black is lost (41...♘e8 42 h5 ♘d6+ 43 ♔g6) and played until: 42 g6 ♔f8 43 h5 d4 44 h6 ♔g8 45 h7+ ♔h8 46 ♔e6 ♘f8+ 47 ♔f7! Resigns

3

Okay, it can’t be delayed any longer. This is the brilliancy that made Lasker famous. But it was for the wrong reasons. Thanks to it, he became known for his originality in combinational play. But his combination had been played before. What is generally overlooked is that White’s victory is based on a well-grounded plan that was designed to create a huge mismatch on the kingside.

Lasker – Bauer Amsterdam 1889Birds Opening (A03)

1

f4

d5

2

e3

♘f6

3

b3

This was considered a sophisticated plan at the time. White obtains a powerful bind after 3...c5 4 ♘f3 ♘c6?! 5 ♗b5! ♗d7 6 ♗b2 followed by ♗xc6 and ♘e5 – a plan that served Nimzovich well in the 1920s just as it did for Fischer in 1970. Today’s players recognize it in reversed form, from lines of the Bogo- and Queen’s Indian.

3

...

e6

Savielly Tartakower suggested White was avoiding ♘f3 because he didn’t want to rule out ♕f3 and ♘h3. But this is an error that Black should punish with 3...d4!.

4

♗b2

♗e7

5

♗d3

b6

6

♘f3

♗b7

7

♘c3!?

Henry Bird had tried nearly every piece configuration available to make White’s first move work. Along with ♘a3 and ♘bd2, as well a quick ♗b5+ and ♗e2, he experimented with ♗d3 and ♘c3-e2.

For example, Bird-Burn, match 1886, went 1 f4 d5 2 ♘f3 e6 3 e3 ♘f6 4 b3 ♗e7 5 ♗b2 0-0 6 ♗d3 c5 7 0-0 ♘c6 8 ♔h1 a6 9 a4 ♗d7 and now 10 ♘c3 ♘b4 11 ♘e5 and ♘e2. That’s the same basic recipe Lasker has in mind: Shift everything to the kingside.

7

...

♘bd7

8

0-0

0-0

9

♘e2

Another rightward shift, used by Tchigorin, is ♘e5, ♕f3 and ♘d1-f2-h3-g5.

9

...

c5

Jean Dufresne, who helped make this game famous in his Das Buch der Schachmeisterpartien, recommended 9...♘c5 and a quick ...♘xd3, which would equalize.

10

♘g3

In light of what follows one might have expected 1 f4 to become a regular part of Lasker’s arsenal. Yet he never played it again except for exhibition games.

10

...

♕c7

White has to begin a plan before Black gets going with ...c4, or ...a6/...b5 first. White has a logical idea. If he can trade off all four knights, what remains on the kingside is one Black piece to defend against White’s queen, king’s rook and two bishops.

11

♘e5

White is already threatening 12 ♘h5 and 13 ♘xd7 – and surely must have seen the basic idea that would make him famous, that 12 ♘h5 ♘xh5 could be met by 13 ♘xd7 ♕xd7 14 ♗xh7+! as in the game.

11

...

♘xe5

White’s last move granted Black another chance for ...d4. After 11...d4 12 exd4 cxd4 Black’s queen’s bishop diagonal is opened, White’s diagonal is closed and the c2-pawn becomes a target on a half-open file. Black’s idea is tactically based on 13 ♗xd4 ♗c5!, which regains his pawn and equalizes. However, 13 ♕e2 and 14 ♖ae1 is much better, as Kasparov pointed out, e.g. 13...♕d6 14 ♖ae1 ♘c5 15 f5.

12

♗xe5

This move invariably goes by without a comment but 12 fxe5 deserved a look. White is threatening a ♘f6+ sack following 12...♘d7 13 ♘h5 and would be better after 12...♘e4 13 ♗xe4 dxe4 14 ♕g4.

However, he’ll be lucky to get a perpetual check after, say, 12...♘d7 13 ♘h5 ♘xe5 14 ♘xg7 ♔xg7 15 ♕g4+ ♔h8 16 ♗xh7 d4.

12

...

♕c6

The immediate 13 ♘h5 allows Black to threaten mate with 13...d4! and buy time for a safe ...♘xh5.

13

♕e2!

Kasparov called this a psychological trap. White seems to be threatening 14 ♗b5 but his real goal is to play 14 ♘h5, which is stronger now that g2 is protected and 14...d4 would not threaten mate.

13

...

a6??

But there is another good explanation for this move that has nothing to do with psychology. Black’s counterplay comes from ...c4, which White just delayed by preventing 13...b5. Bauer, whose promising career was cut short at age 29 by tuberculosis, may have simply been preparing 14...b5 and what he overlooked was the sacrifice of both bishops. As in many great games, it is easy to find improvements (13...♘e4/14...f6 and even 13...g6).

14

♘h5!

Thanks to White’s last move, 14...d4 could be ignored – 15 ♗xf6 ♗xf6 16 ♕g4!, e.g. 16...e5 17 ♗e4! ♕xe4 18 ♘xf6+ or 16...♔h8 17 ♖f3 and wins with 18 ♘xf6 gxf6 19 ♕h4 (or 17...♖g8 18 ♗xh7!).

14

...

♘xh5

There are several quick losses such as 14...♘e8 15 ♗xg7!. The best try was 14...♖fd8 but 15 ♘xf6+ ♗xf6 16 ♗xh7+! (16...♔xh7 17 ♕h5+ ♔g8 18 ♗xf6 gxf6 19 ♕h6!) or 15...gxf6 16 ♕h5 ♔f8 17 ♕h6+ lose eventually.

15

♗xh7+!!

Not 15 ♕xh5 because of 15...f5, closing White’s window of opportunity (16 g4? d4 or 16 ♖f3 ♗f6 17 ♖h3 h6).

15

...

♔xh7

16

♕xh5+

♔g8

17

♗xg7!

This and 15 ♗xh7+!! established Lasker’s reputation, much like Carlos Torre’s 25 ♗f6!! against Lasker at Moscow 1925 and Fischer’s 17...♗e6!! against Donald Byrne. The 2 bishop-sack has been copied dozens of times and dubbed “Lasker’s Combination,” the title of a 1998 book devoted to it.

But this raises a question that will recur in these pages. Just how original was Lasker? There had been published examples of the 2 bishop-sack before, played in Great Britain in 1867 and 1884. Those combinations were carried out by masters (Cecil de Vere and John Owen) much better known than Lasker was in 1889. Why isn’t it “de Vere’s Combination”?

One school of thought would argue: What counts is who played an idea for the first time. Lasker doesn’t deserve the credit for coming in third.

Another school replies: But Lasker was almost certainly unaware of the British games. (They were little known until mentioned in the British Chess Magazine in 2003.) Therefore Lasker was being original in terms of his own understanding of chess.

Besides, this school would argue, the Bauer game was played in an international tournament, one of the few held in the 1880s. Surely a player who first tests his ideas in major events deserves the credit. That’s why openings such as Alekhine’s Defense or the Benko Gambit have those names even though others played the moves earlier.

The argument can go back and forth: Is every 10-year-old who discovers the optimal strategy in tic-tac-toe being original simply because they didn’t know what every previous 10-year-old had discovered?

Back to Bauer ...

17

...

♔xg7

18

♕g4+

♔h7

The prettiest finish is 18...♔f6 19 ♕g5 mate.

19

♖f3

e5

If not for White 22nd move, this would be a winning defense.

20

♖h3+

♕h6

21

♖xh6+

♔xh6

22

♕d7!

Necessary and sufficient. Black will have only a rook and bishop to battle a queen and two pawns.

22

...

♗f6

23

♕xb7

♔g7

Or 23...exf4 24 ♕xb6 ♔g7 25 ♖f1 and wins.

24

♖f1

♖ab8

25

♕d7

♖fd8

26

♕g4+

♔f8

27

fxe5

Since 27...♗xe5 loses to 28 ♕f5 f6 29 ♕xe5, Black played 27...♗g7. The rest was: 28 e6 ♖b7 29 ♕g6 f6 30 ♖xf6+ ♗xf6 31 ♕xf6+ ♔e8 32 ♕h8+ ♔e7 33 ♕g7+ ♔xe6 34 ♕xb7 ♖d6 35 ♕xa6 d4 36 exd4 cxd4 37 h4 d3 38 ♕xd3 Resigns

Scroll ahead to 1914: World Champion Lasker has won the St. Petersburg super-tournament. Tarrasch, his bitter rival, finished fourth but consoled himself with a brilliancy prize victory. However, it was only the second brilliancy prize because Tarrasch’s winning idea, a 2 bishop-sacrifice, seemed to lack...something.

At the final banquet, Tarrasch looked for an ally to appeal the prize jury’s decision. According to Pyotr Romanovsky, who was present, he found himself asking Lasker for support. “Isn’t it true, Doctor, that my victory over Nimzovich was a genuine creation of art?” he asked.

“Oh, yes, without a doubt,” Lasker replied. “Similar games are only played once in...25 years.”

4

Early in his career Lasker began to recognize that he would be facing some opponents over and over, and that he could use his insights into their styles to his advantage. Today this is obvious. Every tournament player wants to have extra information: Which opponents play well in time pressure and which don’t, who is a swindler and who falls for swindles, and so on. We wouldn’t call it psychology and in Lasker’s youth no one did either. His success against Jacques Mieses – nine wins and four draws in 13 games – is more a case of his understanding of human nature. Mieses was among the world’s top 20 players at the turn of the century and a feared attacker. Lasker sought ways to stop him from attacking. In their 1889-90 match, for example, he switched from 1 e4 to 1 d4 and even 1 ♘f3.

Mieses – Lasker Exhibition game, Berlin 1889Vienna Game, Paulsen Variation (C26)

1

e4

e5

2

♘c3

♗c5

Lasker liked this move, which allows Black to reach a King’s Gambit Declined (after 3 f4 d6) in which he could avoid ...♘c6 and a possible ♗b5 pin. An 1891 game saw Lasker (Black) obtain an edge after 3 f4 d6 4 ♘f3 ♗g4 5 h3 ♗xf3 6 ♕xf3 ♘f6 7 f5? c6! and ...d5.

3

g3

♘c6

4

♗g2

d6

Black’s best formation may be ...♘ge7/...d6 and ...♗e6, with ...a6 added at some point to preserve the c5-bishop. Mieses had won a brilliancy at Breslau 1899 that went 4...a6 5 ♘ge2 d6 6 d3 ♘ge7 7 ♘d5 ♘xd5 8 exd5 ♘e7 9 d4 exd4 10 ♘xd4 – along the lines of Game 2. White won after 10...♘f5 11 ♘e2 ♕f6 12 0-0 ♗d7 13 ♘c3 0-0-0 14 ♗d2 ♖de8 15 ♘e4 ♕g6 16 ♘xc5 dxc5 17 b4! ♗b5 18 bxc5! ♗xf1 19 ♕xf1 ♘d4 20 c6.

5

♘a4

♗e6!?

In the 3 g3 Vienna, Black usually met ♘a4 with ...♗b6 in order to preserve his pawn structure. Instead, Lasker prepares ...♕d7/...♗h3.

6

♘xc5

This capture should be delayed because after ...dxc5 Black can play ...c4.

6

...

dxc5

7

d3

Objectively best is 7...c4 with a slight edge for Black after 8 dxc4 ♕xd1+ 9 ♔xd1 0-0-0+.

7

...

♘f6

But even at this early stage in his career Lasker seemed to have divided the world into two hemispheres – the players whom he might be able to beat in the middlegame and the players who might be able to beat him in the middlegame. Against the latter, Lasker headed for endgames. But Mieses lived in another hemisphere.

8

♘e2

♕d6

Now that it is available, d6 is a better square for the queen because it allows the bishop to retreat (after f2-f4-f5) and protects c5 (compared with 8...♕d7 9 ♗e3 c4?! 10 d4).

9

f4

Against 9 ♗g5 Black might reply 9...♘g8! and ...f6/...♘ge7.

9

...

h5

An obvious plan – yet databases cite only a few previous examples of Black playing ...h5 in the 3 g3 Vienna.

10

f5

The modern way of handling the position is 10 h3 and if 10...h4 then 11 g4. This is best even though it surrenders control of e5 (11...exf4 12 ♗xf4 ♘e5).

10

...

♗d7

11

♗g5

The bishop discourages ...h4.

11

...

♘h7!

12

♗e3

0-0-0

White has to decide around here what kind of middlegame he wants. If he castles kingside Black can open the position with ...♖dg8/...g6, followed by ...♘e7 and ...h4. If, on the other hand, White castles queenside (13 ♕d2, 14 0-0-0) his king is vulnerable to ...f6/...♗e8-f7 and ...♘d4 or ...♘b4, as in Game 28.

13

♘c3

♘f6

14

♘b5

Mieses picks a third option, taking aim at the enemy king (♘b5, c2-c3, ♕a4, and possibly a2-a3/ b2-b4) while temporarily keeping his own in the center. A better idea is 14 ♗g5 followed by ♗xf6 or ♘d5, e.g. 14...c4 15 ♗xf6 gxf6 16 ♘d5 cxd3 17 ♕xd3.

14

...

♕e7

Black is ready for 15...c4 (and 16 dxc4 ♗xf5). White should forget about the attack and take precautions (15 ♕e2).

15

c3?

c4!

There is more to this than 16 ♘xa7+ ♘xa7 17 ♗xa7 b6. White can obtain compensation after 18 a4 ♔b7 19 a5 ♔xa7 20 axb6+ ♔xb6 21 dxc4 but Black does better with 19...♖a8 or just 18...♗c6 (19 a5 cxd3 20 axb6 d2+!).

16

b4

Better was 16 ♕a4! a6 17 dxc4! because of 17...axb5 18 ♕a8+ ♘b8 19 ♗a7. Black should keep the initiative with 17...♘g4! 18 ♗g1 ♕g5.

Lasker revealed little of his thought processes. We don’t know why he rejected moves or which he considered or even how many candidate moves he looked at. But we can make some educated guesses.

Here, for example, he must have considered 16...a6, which defends and attacks.

Since White appears lost after 17 ♘a3 cxd3, he would have wondered about the piece sack 17 a4 axb5 18 axb5. He almost certainly didn’t stop there but also looked at the pawn-sack 17...cxd3 18 ♗c5 ♕e8 19 ♕xd3 ♗xf5 20 ♕e3.

16

...

♘xb4!

Grabbing material in either line seems to favor Black. Yet Lasker makes his own sack, perhaps because it is much easier to calculate. For example, 17 cxb4 ♕xb4+ and 18...♗xb5 is clearly very good.

17

♘xa7+

♔b8

18

cxb4

♕xb4+

Now 19 ♕d2 ♕xd2+ (or 19...c3) and 20...b6 allows Black to regain his piece favorably, as does 19 ♗d2 ♕c5.

19

♔f1

♘g4!

Better than 19...b6 20 ♖c1 with chances for both sides (20...♔xa7 21 ♖xc4 ♕d6 22 a4 or 20...♗a4 21 ♕d2).

20

♗g1

♗a4

21

♖b1!

Finding shots like this is what Mieses did well. The endgames favor Black (21 ♕e1 ♕xe1+ 22 ♔xe1 b6). But in the middlegame of 21 ♖b1 ♕a5 there is no threat of 22...♗xd1 because of 23 ♘c6+. If the queen goes to a3 or c3 White has ♘b5.

21

...

♕a3!?

There was quite a bit to calculate here, including 21...♕c3 22 ♘b5 ♕xd3+, which favors Black slightly, and 22...♗xb5 23 ♖xb5 ♖xd3 24 ♕b1, which seems promising for White.

Retreating the queen to a5 allows White a nice resource of 22 h3! after which 22...♖xd3 23 ♕e1 ♕xe1+ is a small edge for Black and 22...cxd3! 23 hxg4 d2 might win.

22

♕e2

A key point of Black’s move is that 22 ♘b5 ♗xb5 23 ♖xb5 ♖xd3 24 ♕b1 is much better with Black’s queen on a3, rather than c3, because he can continue 24...♖hd8 25 ♖xb7+ ♔a8! 26 ♖a7+ ♕xa7 27 ♗xa7 ♖d1+.

White can keep the game going with 26 ♗f3! ♖xf3+ 27 ♔g2. However, Black has 27...♘e3+! because 28 ♔xf3 ♘f1+ 29 ♔e2 ♘d2 forces White into a lost ending (30 ♖a7+ ♕xa7 31 ♗xa7 ♘xb1). White is also doomed following 28 ♗xe3 ♖xe3 or 28 ♔h3 h4.

22

...

♖xd3!

So that 23 ♕b2? ♖d1+.

23

h3

Now 23...♘e3+ 24 ♗xe3 ♖xe3 25 ♕xc4 ♔xa7 favors Black’s extra pawn. But Mieses was a member of the hemisphere who could be mated.

23

...

♖hd8!

The threats of 24...♖d1+, 24...♖d2 and 24...c3/... c2 are too much.

24

hxg4

c3

Also winning was 24...♖d2 25 ♕xc4 ♕xg3 26 ♖h2 ♖d1+ or 25 ♕e3 ♖d1+.

25

♘c6+

White couldn’t meet the ...c2 threat with 25 ♗e3 c2 26 ♖c1 ♖xe3 or 25 ♘b5 ♗xb5 26 ♖xb5 ♖d1+ 27 ♔f2 ♖8d2.

25

...

♗xe6

26

♗e3

26

...

c2!

The last chance to blunder was 26...♖xe3 27 ♕xe3 c2 28 ♖xb7+! and ♕xa3.

27

♕xc2

♖xe3

Now 28 ♕xc6 ♖d1+ 29 ♔f2 ♖e2+! mates (30 ♔xe2 ♕d3+ 31 ♔f2 ♕d4+).

28

♔f2

♖c3

Resigns

In view of 29 ♕b2 ♕c5+ or 29 ♕e2 ♕c5+ 30 ♔f1 ♖c2 31 ♕f3 ♗b5+ 32 ♖xb5 ♖d1+ and mates.

5

In Lasker’s early years the prevailing wisdom about openings is that there were two kinds – good ones and bad ones. Steinitz, representing the “New School,” agreed on this with Tchigorin, of the “Old.” It was the responsibility of masters to figure out which openings were inherently good and play them. When Steinitz and Tchigorin met in the world championship matches of 1889 and 1892 they stuck to their favorite openings – and that cost each man point after point.

Lasker took a different point of view. There were, of course, some openings that were stinkers. But no openings were absolutely best, he felt. Most were neither good nor bad but simply “playable.” An opening may be unpopular – like the Evans Gambit in the decades before 1995 or the Scotch Game before 1990 – but that didn’t make it unusable.

Blackburne – Lasker Match, seventh game, London 1892Center Game (C22)

1

e4

e5

2

♘c3

♘f6

3

d4!?

The opening of this game is often incorrectly given as 2 d4 exd4 3 ♕xd4 ♘c6 4 ♕e3. Why did Blackburne choose the other, highly unusual route? Perhaps to avoid the defense that he adopted himself as Black, with 4...g6, 5...♗g7 and ...♘ge7 followed by an early ...d5 or ...f5.

3

...

exd4

4

♕xd4

♘c6

5

♕e3

Everyone knows the Center Game is bad. “The early development of White’s queen is a serious breach of the basic rules of development,” said Batsford Chess Openings. “A serious breach of principles,” wrote Reuben Fine. “A serious breach of principles,” echoed Larry Evans in Modern Chess Openings. (No one explains why violating the same principles – a tempo down – is perfectly all right in the Center Counter Defense.)

5

...

g6

For most of the 20th century the book refutation of the Center Game was 5...♗b4 6 ♗d2 0-0 7 0-0-0 ♖e8. A Capablanca analysis that began 8 ♕g3 ♘xe4 9 ♘xe4 ♖xe4 10 ♗f4 ♕f6 was usually cited (with an accompanying note that 8...♖xe4!? may be even better).

But in the 1960s Yakov Estrin and Vasily Panov, in an influential Russian book, argued that 10 c3 ♗f8 11 ♗d3, rather than 10 ♗f4, offered serious compensation. In addition, 8...♖xe4 wasn’t as strong as it seemed because of 9 a3 ♗d6 10 f4.

Few modern players have looked at any of this. When Karpov was confronted with 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 ♕xd4 ♘c6 4 ♕e3 at his first Olympiad, he replied 4...d6? 5 ♘c3 ♘f6 6 ♗d2 ♗e7 7 0-0-0 0-0 and nearly lost to an obscure amateur after 8 ♕g3 a6 9 f4 b5 10 e5!.

6

♗d2

♗g7

7

0-0-0

0-0

One of the best-known collections of Lasker’s games, by Fred Reinfeld and Fine, gave a possible continuation as 8 ♗c4 ♘a5 9 ♗e2 d5, with exclamation points for Black’s moves. But 10 exd5 ♘xd5 loses to 11 ♕c5!.

8

f3

d5!

Now, however, White is in danger of getting the worst of it because 9 exd5 ♘xd5 10 ♘xd5? ♕xd5 11 ♗b4, which he may have intended, is bad after 11...♕xa2 12 ♗xf8 ♕xb2+. Other complications (9 ♕e1 dxe4! 10 ♗g5 ♕e8) favor Black.

9

♕c5

Best was 8 exd5 ♘xd5 9 ♕c5!, since 9...♘xc3 10 ♗xc3 ♗h6+ 11 ♗d2 is harmless.

9

...

dxe4

Here’s a paradox. Early in his career Lasker played his simplest games yet relied on calculation to a greater degree than later on. The explanation is that the older Lasker had acquired an instinct for playing moves he didn’t have to calculate. Here, for example, the older Lasker might have played 9...d4 and obtained a favorable middlegame after 10 ♘d5 ♗e6 without having to look half as far into the future as 9...dxe4 requires.

10

♗g5

♕e8

Forced say Reinfeld/Fine. But 10...♕e7 is perfectly playable because 11...♕xe7 ♘xe7 12 ♘xe4 ♘xe4 13 ♗xe7? allows 13...♘f2! with a winning advantage.

11

♗xf6

Experience tells White to cut his losses. He will only be slightly worse in the coming endgame, whereas he could get killed in the 11 ♖e1 middlegame after 11...b6 12♕f2 ♕e5.

11

...

♗xf6

12

♘xe4

♗g7

13

♗b5

♕e5!

Obviously better than 13...♗d7 14 ♘e2. Black forces an ending (14 ♗xc6? ♕xb2+) in which the two bishops guarantee some degree of superiority.

14

♕xe5

♘xe5

15

♘e2

White’s bishop and king’s knight compete for the same squares now. But 15 f4, intending 16 ♘f3, allows 15...♘g4. Even better is 15...a6!, with the idea of driving the bishop off the diagonal so Black can meet 16 ♗f1 ♘g4 17 ♘f3 with 17...♖e8. If 16 ♗a4, Black has 16...♘c4.

15

...

a6

Black uses forcing moves when they present White with a choice between two equally unpleasant alternatives. After 16 ♗a4 ♘c4 17 ♘2c3 ♗f5 or 17 ♘d4? ♘e3 Black is better.

16

♗d3

16

...

f5!

In My System Nimzovich described a technique he called the “hemming-in process” – “A pawn mass...guided by a pair of bishops can roll forward fairly far and this leads to the imprisoning of the enemy knights.” He illustrated this with a Tarrasch game but the ideas are similar here: 17 ♘c5 b6 18 ♘b3 c5 or 17 ♘g5 h6 and 18...g5.

17

♘4c3

♗e6

Black can win a second “minor exchange” whenever he wants. But 17...♘xd3+ 18 ♖xd3 ♗e6 19 ♘d5 allows White more freedom than he deserves.

18

♔b1

♖fd8

19

♘f4

♗f7

20

♗e2

♘c6!

What is impressive here is how Lasker avoids forcing variations that might allow his opponent out. Here, for example, 20...♘c4 threatens ...♗xc3 and ...♘a3+. But it invites 21 ♗xc4! ♗xc4 22 ♘cd5, e.g. 22...♗e5 23 b3 ♗b5? 24 ♘e6! with advantage.

21

♖xd8+

White takes the opportunity to trade rooks before ...♘d4 denies him. Other active ideas fail tactically – 21 ♘cd5? g5! and 21 ♘fd5 ♗d4! (22 ♘xc7? ♖ac8 or 22 ♗c4 ♗xc3! 23 bxc3 ♘a5).

21

...

♖xd8

22

♖d1

♖e8

Black should retain rooks until he has a kingside target for his king. This move threatens 23...♗xc3 24 bxc3 g5, winning a piece.

23

♗f1

Forcing matters now with 23...g5 24 ♘fd5 ♗