14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

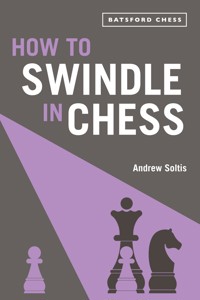

A book by stalwart chess writer on an aspect of chess that is quite common, but little is written about, swindling in chess. In chess, a swindle is a ruse by which a player in a losing position tricks his opponent, and thereby achieves a win or draw instead of the expected loss. Renown chess writers Horowitz and Reinfeld observe that swindles, "though ignored in virtually all chess books", "play an enormously important role in over-the-board chess, and decide the fate of countless games". Andrew Soltis, American chess journalist, says swindles are not accidental or a matter of luck. Swindling is a skill. But there has been almost nothing written about how to do it, how to make yourself lucky in chess. Swindling means setting traps that exploit an opponent's over-confidence. It means choosing the move that has the greatest chance of winning, rather than the move that has the least chance of losing. Soltis' new proposal will explain to players of all levels how to do just that with plenty of examples to explain along the way.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

How to Swindle in Chess

Andrew Soltis

Contents

Chapter One Outrageous Fortune

Chapter Two Swindle-Think

Chapter Three Traps

Chapter Four Make Yourself Lucky

Chapter Five The Swindlee

Chapter Six False Narrative/Bluffing

Chapter Seven Panic Worthy

Chapter Eight The Swindling Process

Chapter Nine Swindler Versus Swindlee

Chapter Ten Royal Swindles

Chapter Eleven The Very Lucky

Quiz Answers

Chapter One:

Outrageous Fortune

Victories show how well you play. Defeats show how unlucky you are.

This is how we often feel when we lose after achieving a promising position: It was an accident. You were on your way to a well-deserved victory. But suddenly something – something unfair – spoiled it.

But if luck is random and accidental, why are some players luckier than others?

Anand – Ivanchuk

London 1994

White to play

Black’s threats of 23...♗xh1 and 23...♗e3+ must win material. White could have prepared to defend. Instead, he prepared to be lucky, with 23 ♖d3!.

This stops ...♗e3+ but also threatens to mate with 24 ♖h3 and 25 ♕h8. Experienced players – especially experienced swindlers – try to find moves that not only defend but give them a chance to win.

This was a speed game but Black had time to look at 23...♗xh1. Of course. he saw that on the expected 24 ♖h3 there would be only one good reply, 24...♗e3+!.

That looks strong because 25 ♘d2 allows 25...♕a1 mate and 25 ♔d1 invites a series of powerful checks (25...♕b1+ 26 ♔e2 ♕xc2+ 27 ♔xe3 ♕e4+! 28 ♔d2 ♖fd8+ or 28 ♔f2 ♕f5+ 29 ♔g1 ♕b1+ etc.).

Therefore the normal course of the game was 23...♗xh1 24 ♖h3 ♗e3+ 25 ♖xe3 and the outcome would be highly uncertain.

Instead, Black shot back 23...♖ac8!!.

White to play

This is stronger than 23...♗xh1 for the same reason White chose 23 ♖d3: It gives him a chance to force a win. If White followed his plan, 24 ♖h3, then 24...♖xc2+! 25 ♔xc2 ♖c8+ hands Black a strong attack.

Black’s move did something else, perhaps unintended. It made it much more difficult for either player to calculate accurately. The tactics have become sharper.

That increases the luck factor: White could see how 24 g6 fxg6 25 ♘xg6 threatens 26 ♘e7 mate.

But only if he had plenty of time could he foresee what might happen after 25...♖xc2+ 26 ♔xc2 ♖c8+. (A perpetual check is likely: 27 ♔d1 ♕b1+ 28 ♔e2 ♗xh1 29 ♘e7+.)

Instead, luck intruded. He played 24 ♖h3? and the position became chaotic, 24...♖xc2+! 25 ♔xc2 ♖c8+. As the players got closer to forfeiting on time, the luck factor was soaring.

White to play

White could safeguard his king with 26 ♖c3!. But that gives up hope of ♕h8 mate. The initiative would be Black’s and he would have all the winning chances after 26...♗e4+!.

White went for broke with 26 ♔d1?? and kept his ♕h8 mate plan alive.

After 26...♕b1+! 27 ♔e2 he would win in case of 27...♕c2+?? 28 ♘d2!.

Then Black would only have a few checks left, such as 28...♗f3+ 29 ♔xf3! ♕f5+. He could safely resign following 30 ♔g2.

But only when the game is over can you be sure about tactical shots like these. That is when you know which player was the lucky one. Or, rather, the luckier one.

Black to play

With 27...♕e4+! it seemed certain that Black was the luckier. He could now force checkmate in, at most, five moves.

It would be faster after 28 ♔d1 ♕c2 mate and 28 ♔f1 ♕e1 mate.

White kept the game going with 28 ♔xf2 ♖c2+ 29 ♔f1. The game should have ended with 29...♕xh1 mate.

Had that happened, White could have honestly said it was an unfair result. After all, he had found a great move in 23 ♖d3!, when it seemed his only options were dismal – such as 23 ♕e2? ♗xh1 that only prolong a losing game.

Besides that, he would probably have drawn if he had had the time to calculate 24 g6!.

But he didn’t have to complain about bad luck that day.

Black to play

Incredibly, Black overlooked 29...♕xh1 mate. He played 29...♕f4+???.

This should have turned certain victory into probable defeat following 30 ♘f3!. White had renewed the threat of 31 ♕h8 mate, while holding an extra rook and a piece. Black would run out of checks soon after 30...♖c1+ 31 ♘xc1 ♕xc1+ 32 ♔g2.

But White only had slightly more time than Black. After 30...♔f8 he passed up the routine and easily winning 31 ♕h8+ and 32 ♕xg7.

Instead, this strange game continued strangely, 31 g6?? ♕c4+ 32 ♔g1 ♕xb3 33 ♕e5 ♖c1+ 34 ♔f2 ♕c2+ 35 ♔e3 ♕b3+ 36 ♔e2? ♕c4+? (36...♗xf3+) 37 ♔f2 ♕c2+ 38 ♔e3 ♕b3+!.

White to play

White avoided perpetual check with 39 ♔f4??. He was lost, 39...♖c4+! 40 ♘d4 ♕xh3 41 ♕b8+ ♖c8 42 ♕d6+.

But as Black played 42...♔g8! his flag fell. And these were two of the very best players in the world.

One-player luck

What can we make of this? Clearly, the outcome was extremely lucky. That is, unexpected. But was it just horribly played by both players?

To say that we have to look only at the ghastly moves and ignore the splendid ones (23 ♖d3!, 23...♖ac8!!, 24...♖xc2+!, 27...♕e4+!, 30 ♘f3!, 38...♕b3+!, 39...♖c4+!).

White played more of the bad moves and Black found more of the good ones. But they both chose to increase the likelihood of a lucky result. Both players wanted to be the lucky one.

As much as we ascribe success in chess to other factors, luck abounds. It happens at the amateur level and among super-GMs. “We have a lucky champion,” Vladimir Kramnik said when then-world champion Garry Kasparov had once again escaped from a bad position against him.

Yuri Averbakh was a promising scientist when he considered switching careers and becoming a professional chessplayer. A friend who was a strong master told him he was “out of his mind.” It is crazy to get into a line of work, the friend said, “where so much depends on luck.”

Lucky results are by nature unfair, sometimes outrageously so. A player who did nothing but try to avoid losing gets a full point. His opponent commits suicide. We can call these cases of one-player luck:

Bu – Nakamura

Gibraltar 2008

White to play

Black had constructed an impregnable fortress earlier. White’s queen cannot win unassisted. He managed to send his king on a voyage from c5 to a7, then c8 and d8, and finally c7. But there was no progress to be made.

Yet there was a decisive result. White played 68 ♔d6?? and permitted 68...♘e4 mate.

Black was lucky. But the finish wasn’t a true swindle. Black resisted. But he did nothing to provoke 68 ♔d6.

A swindle is something else. The would-be swindler chooses moves that do more than just resist. He defends actively, often by setting traps. The more primitive the trap, the more an unexpected result seems lucky. Here’s an example from the very first international tournament.

Staunton – Anderssen

London 1851

White to play

Black is winning. The white knight is attacked and pinned because 29 ♘f2 loses to 29...♖xg2+.

White could try 29 ♕xd5 hxg4 30 hxg4, thinking he would have two pawns as compensation for the knight.

But that allows an immediate mate by a queen check at h6 or h7.

Only slightly better is 30 fxg4 in view of 30...♖5xg4! (since 31 hxg4 allows another mating queen check).

White played the desperate 29 ♘f6+!.

It was confusing to Black, if only because he had six legal responses.

Black to play

The first was the most natural, 29...gxf6. But after 30 ♕xe6+ Black’s win is gone:

White can take the bishop with check after 30...♔h7? or 30...♔g7?.

He can meet 30...♔h8 with 31 ♕xe7 because 31...♖xg2+ 32 ♖xg2 ♖xg2+ 33 ♔h1 ends Black’s mating attack.

Then Black has to find 33...♖h2+! 34 ♔xh2 ♕g3+ to draw by perpetual check.

There was more for Black to look at. He must have seen that he could meet 29 ♘f6+ with 29...♔h8.

But once again he would have nothing much after 30 ♕xe6 ♖xg2+ 31 ♖xg2 ♖xg2+ 32 ♔h1 or just 30 ♕e8+ ♕xe8 31 ♘xe8.

So, Black played the only move that discouraged ♕xe6. The game ended with 29...♔f7?? 30 ♕e8 mate.

That swindle required the efforts of both players. It was, of course, an unfair result. Black could have won with 29...♗xf6! 30 ♕xe6+ ♔h7! because of 31 exf6 ♖xg2+ 32 ♖xg2 ♖xg2+ 33 ♔h1 ♕g3!.

Nevertheless, 29 ♘f6+ was the pragmatic move because it had the greatest chance of saving the game.

Practical versus “computer-best”

Chess has gotten a lot more sophisticated since 1851. We defend much better today. But we are also much better at swindling.

Topalov – Glavina

San Cugat 1992

White to play

White has barely survived since he blundered away his queen earlier. Black’s last move, 49...c3, prepared to queen a pawn and end resistance.

A passive defense such as 50 ♖e2 would lose in various ways. One is 50...d4 and ...d3. Another is 50...c2 51 ♖xc2 ♗e5 followed by either 52...♕f4+ or 52...♗xc7 53 ♖xc7+ ♔xe6.

White kept hope alive with 50 ♘e8!, attacking the f6-bishop.

It is not just the move with the best chance of avoiding a loss. It is the move with the best chance of winning: 50...♗d4?? 51 ♘d6+ ♔g8 52 ♖e8+ ♔h7 53 ♖2e7+.

Then 53...♔h6 54 ♘f7+ or 53...♗g7 54 ♖h8+! ♔xh8 55 ♘f7+.

Only slightly better is 50...♗d8? in view of 51 ♘d6+ ♔g8 52 ♘f5 c2 53 ♖c6 and White has turned the game around.

But he was lost after 50...c2!.

White to play

White’s 50 ♘e8! was objectively the best move available. The swindle begins now: The “computer-best” move – the one recommended by engines – is a bad choice.

Computers recommend 51 ♖xf6+. Black has nothing better than 51...♕xf6 52 ♘xf6 c1(♕) with a long ♕-vs-♖+♘ endgame ahead.

White might draw if he could play 53 ♘xd5. But that loses to 53...♕h1+ and ...♕xd5.

So he would have to play another knight move and try to defend after, say, 53...d4. Computers say White might hold on for 30 moves before he gets mated.

But White realized he had greater practical chances with 51 ♘xf6. Then 51...♕xf6?? loses because 52 ♖xf6 is check and White has time for 53 ♖c3.

So play went 51...c1(♕)! 52 ♖e7+.

Black to play

This is a true swindle attempt because:

(a) With proper play, Black would win more quickly than if White had played the computer-best 51 ♖xf6+, and

(b) White is setting traps. So far they are simple ones – 52...♔xf6?? 53 ♖3e6 mate and 52...♔f8?? 53 ♘h7+.

Black is playing well and 52...♔g6! should have won. White had one trick left, 53 ♘h5!. It threatened to win with 54 ♖3e6+.

It is surprising to see that even with two queens, Black would achieve nothing from checks (53...♕h1+ 54 ♔g3 ♕g1+ 55 ♔f3 ♕d1+ 56 ♔g3).

But when you have two queens you have the luxury of giving one away: 53...♕xe7! 54 ♖xe7 ♕xa3+ 55 ♖e3 ♕a1.

White to play

This ♕-vs.-♖+♘ ending is much easier to win than the one that might have arisen after 51 ♖xf6+ ♕xf6. Black doesn’t have to create a passed queenside pawn now. They already exist. He can just push one to the eighth rank.

White can do little to stop that. He would lose soon after 56 ♘f4+ ♔f7 57 ♘xd5? ♕h1+ and ...♕xd5.

A better try is 57 g5 and 58 g6+. This looked dangerous. Looks help create swindles.

But this look is a bluff. After 57...b4 58 g6+ ♔f8 White can safely resign (59 ♘e6+ ♔g8 or 59 h4 b3 60 ♖xb3? ♕d1+).

But Black correctly saw that on 56 ♘f4+ he can restrain the white pawns with 56...♔g5 and also threaten to win the knight (57...♕f1+!).

If White safeguarded the knight with 57 ♘e2, Black wins by pushing (57...b4 or 57...a5 and 58...a4).

So White defended against ...♕f1+ with 57 ♔g3 and then 57...♕g1+! 58 ♘g2.

Black to play

White’s knight has become a pinned, inactive piece. Black had no reason to fear 59 ♖e5+ ♔g6 60 ♖xd5 because his remaining pawns are too strong (60...b4).

He must have noticed that 59 h4+ was possible. But the king could safely retreat to f6 or g6.

Since there was apparently no threat, Black played 58...a5??.

But he resigned after 59 ♖e6!. There was no way to stop 60 h4 mate.

Championship Swindling

Why do some great players become world champion and others don’t? Paul Keres – one of those in the “don’t” category – had an answer: Champions are lucky. The others aren’t.

Keres cited the 1959 Candidates tournament. He scored an impressive three wins out of four games against Mikhail Tal. But Tal won the tournament and became world champion the next year.

Keres particularly remembered one game, which Tal drew from a dead lost position. ‘You cannot fight against such luck,” Keres told fellow GM Bent Larsen. Games like that convinced Keres that “fate was against him,” Larsen recalled.

Tal’s luck, like that of all great swindlers, was a collaboration. But it was not a collaboration of him and some mysterious force of destiny. It required the unintended cooperation by his opponent, who had been world champion just one year before.

Smyslov – Tal

Candidates tournament 1959

1 e4 c5 2 ♘f3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 ♘xd4 a6 5 ♗d3 ♘c6 6 ♘xc6 bxc6 7 0-0 d5 8 ♘d2 ♘f6 9 ♕e2 ♗e7 10 ♖e1 0-0 11 b3 a5 12 ♗b2 a4 13 a3 axb3 14 cxb3 ♕b6 15 exd5 cxd5 16 b4 ♘d7 17 ♘b3 e5 18 ♗f5 e4 19 ♖ec1 ♕d6 20 ♘d4 ♗f6 21 ♖c6 ♕e7 22 ♖ac1 h6 23 ♖c7! ♗e5 24 ♘c6!

Black to play

Tal would lose material if his attacked queen goes to e8 (25 ♘xe5 ♘xe5 26 ♖xc8).

The computer-best 24...♕f6 would also lose after 25 ♗xe5 ♘xe5 26 ♘e7+ and ♗xc8.

Moreover, Tal had spent so much time trying to conjure up counterplay earlier that he only had two or three minutes to reach the time control at move 40.

“I had nothing to lose,” Tal admitted afterward. “I attempted only to complicate my opponent’s task in any way possible.”

He seized his slim chance for kingside play with 24...♕g5.

This could lose faster than 24...♕f6. The reason is 25 h4! since 25...♕xf5?? 26 ♘e7+ hangs the queen.

So play went 25...♕xh4 26 ♘xe5 ♘xe5 27 ♖xc8.

Black to play

White has won a piece for a pawn. Computers will tell you Black’s best options are 27...♘d3 and 27...♕f4. But they admit that those moves offer almost no survival chances after 28 ♖xa8 ♖xa8 29 ♖c8+ ♖xc8 30 ♗xc8.

Tal’s instinct told him to search for tactics, any tactics that offered hope. He found 27...♘f3+ 28 gxf3 ♕g5+.

Then 29 ♗g4 ♖fxc8 wins back material and 29 ♔h1 ♕h5+ 30 ♔g1 ♕g5+ repeats the position.

White was playing the best moves and that continued 29 ♔f1! ♕xf5 30 ♖xf8+ ♖xf8 31 fxe4 dxe4.

Tal was not playing “best” moves and that is why White’s advantage has grown substantially since 24...♕g5. His opponent assumed Tal was playing badly because he now had only seconds left.

White to play

But Tal had created tactical opportunities on White’s weakened light squares that White’s extra piece – a dark-squared bishop – cannot deal easily with.

Instead, White can use his heavy pieces to defend the kingside. Both 32 ♖c3 or 32 ♕e3 are useful.

White preferred 32 ♕e3 so his queen could go to g3, where it would threaten ♕xg7 mate. That threat would either prompt a losing queen trade (...♕g5) or a weakening of Black’s own kingside (...f6 or ...g5).

Computers say Tal’s 32...♖d8 made matters even worse for him. But for the first time in several moves he was making a real threat (33...♖d3! 34 ♕c5 ♕h3+ or 34 ♕e2 e3).

White answered with the move he had planned, 33 ♕g3, so that 33...f6? 34 ♖c7.

Tal replied 33...g5

White to play

This is the first point in the game when we can say White erred. With 34 ♕c3! f6 35 ♕b3+! he would edge closer to victory.

For example, 35...♔g7 36 ♖c7+ ♔g6? 37 ♕f7 is mate. On 35...♔h8 he has 36 ♖c6 followed by a capture on f6 or even 36 ♖c5! ♕f4 37 ♖c6!.

But when you have as great an advantage as White, you don’t feel that a lot of calculating is necessary. Vasily Smyslov saw something that looked simpler and stronger, 34 ♖c5.

Then 34...♕e6 allows 35 ♖xg5+! (35...hxg5 36 ♕xg5+ ♕g6 37 ♕xd8+).

Tal used his best tactical resource, 34...♖d1+. Once again, White avoided calculating long lines (like 35 ♔e2 ♕d7 36 ♕b8+). He chose the more natural 35 ♔g2 and after 35...♕e6:

White to play

Black is threatening ...nothing. But he keeps creating situations in which his opponent has not-so-simple choices.

Here it looks like there must be a forced mate after 36 ♕b8+ ♔h7 37 ♕h8+ ♔g6 38 ♕g8+ ♔h5. But there is no mate, just an eventual win after 39 ♕c8!.

Rather than calculate lines like that, White assumed he could win with his pawns, 36 b5.

Then 36...♔h7! eliminated a check with ♕b8. That doesn’t seem like much – until you see that Black now has a threat, 37...♖d3!.

For example, 38 ♕e5 ♕h3+ and mates, or 38 ♕h2 ♕g4+.

Both players were now short of time and four moves away from the time control. The natural moves 37 ♖c6 ♕d5 were played.

White to play

This is the position that convinced fans – and Paul Keres – of Tal’s luck.

It looks like the best position White has had all game. And it is: He can win outright with 38 ♕h2! because of the threat of 39 ♕xh6+ and mates.

But to play 38 ♕h2! White had to see that 38...e3+ could be safely met by 39 ♔g3!. Black would almost certainly have resigned then.

But what happened was 38 ♕e5?? ♖g1+!. White may have seen 39 ♔xg1 ♕d1+ 40 ♔g2 ♕g4+ 41 ♕g3 but not 40...♕f3+! 41 ♔h2 ♕h5+ with perpetual check.

The game ended with 39 ♔h2 ♖h1+! 40 ♔g1 ♖g1+ draw. Tal was told after the game that Smyslov had seen 38...♖g1+ but not 39...♖h1+.

It is easy to explain the surprise finish by saying that White missed a tactic. But it took a remarkable effort for Tal to have any tactics after 24 ♘c6!. The final result depended on White’s contribution – and Black’s.

The first time that Pal Benko, another world-class player of that day, played Tal he had a winning position after 39 moves. Then he made three bad moves in a row. He awarded himself a total of five question marks for them. He lost and said it was his first experience with “the legendary Tal luck.” As usual with a swindle victim, he didn’t appreciate what his opponent did to create that luck.

Next-to-Last

Luck is fickle. It can help one player and then switch affections to the other.

That is what happened at the end of the Smyslov – Tal game. But no one appreciated it at the time.

Black to play

Black’s 37...♕d5?? was actually a blunder.

Correct was 37...♕f5! with at least a draw because of the threat of 38...♖d3.

Then 38 ♕e5?? allows 38...♕f3+ and mate next. And 38 ♖c3 ♕xb5 threatens 38...♕f1+ as well as 38...♕xb2.

So Tal was lucky that Smyslov answered 37...♕d5?? with 38 ♕e5??. But if Smyslov had found 38 ♕h2!, fans would say he was the lucky one, because Tal missed 37...♕f5!.

Savielly Tartakower made many wise observations but perhaps the one that is most useful to a competitive player is:

The winner is the player who makes the next-to-last error.

This is an exaggeration but with Tarkakover’s usual kernel of truth: One mistake rarely decides a game. What is typical is a series of mutual errors. This is what a would-be swindler has to expect – and exploit.

Goletiani – Sharevich

St. Louis 2015

White to play

The position is so highly double-edged that any mistake is bound to swing the advantage to one side. In mutual time pressure, mistakes – plural – are likely.

For example, 36 ♗xc3 is obvious. But it turns out badly after 36...bxc3. If the attacked knight moves it allows 37 ...♗e4!, e.g. 37 ♘f3 ♗e4! and ...♕g3! (38 ♔g2 ♗h4).

White found 36 ♗f3! with a threat to win with 37 ♗xd5.

Black needed more than a routine reply. She would face a very hard defense after 36...♕c8? 37 ♕xc8+ ♖xc8 38 ♗xf6 and ♗xd5.

After the game, 36...♔h8! was discovered. Then Black threatens to win with 37...♘g5 (38 ♕xd5 ♖d3). And 37 ♕xf7 ♖c7 is fine (38 ♕-moves ♗xb2).

But she played 36...♖c2??.

White to play

That was the first twist of fate. It seemed that 37 ♗xf6 would lose to 37...♖xd2 followed by 38...♕h2 mate or 38...gxf6.

But what both players overlooked was that 37 ♗xf6 ♖xd2 allows a winning 38 ♗e5! (38...♕xe5 39 ♕c8+ and mates).

If the game had ended with that mate, or after 38...♕d8 39 ♗d4! and 40 ♗xd5, we would know what the final mistake of the game was.

But the effects of 36...♖c2?? were reversed by 37 ♗xd5??.

Why would this seem like the right move? Because it was more forcing than 37 ♗xf6. It threatens mate after 38 ♕xf7+ and 39 ♗xf6. And it wins after 37...♖xb2 38 ♕xf7+ and 39 ♖xf6!.

But Black could have turned a lost position into a winning one with 37...♖xd2!.

That threatens mate on h2. This time 38 ♕xf7+ ♔h8 39 ♗e5 fails to 39...♗xe5 40 ♕f8+ ♗g8!.

Instead, the wheel of fortune was turned again by 37...♗g6?? and then 38 ♗xf6 ♖xd2 39 ♗e5!.

Black to play

This time White saw this move. It works, but not nearly as well in the 37 ♗xf6 ♖xd2 38 ♗e5! version.

Black faced another crucial decision. Both 39...♕d8 and 39...♕b5 would threaten ...♕xd5+.

In either case, 40 ♖xf7 ♕xd5+ 41 ♕xd5 ♖xd5 42 ♖xg7+ would grant White a very good endgame.

But that is the best Black can get now. There was no better 39th move for Black.

In time pressure it is natural to play the most forceful move. Here 39...♕b5 seems better than 39 ...♕d8 because it also threatens 40...♕f1+. It would virtually force White to respond 40 ♖xf7.

But Black chose 39...♕d8!.

White to play

A good swindler knows that often the less forcing move has greater chance of inducing an error because it gives the opponent more choice.

White might consider 40 ♗g2 because it threatens to win quickly with ♕xg6. There is even a pretty mate, 40...♔h7? 41 ♕xg6+! ♔xg6 42 ♗e4+ and so on.

But Black would meet 40 ♗g2? with 40...♕d7. Then the 41 ♕xd7 ♖xd7 endgame is a bit less disadvantageous than the one that would arise after 39...♕b5 40 ♖xf7 ♕xd5+.

Black reaped an unexpected bonus when White passed up both 40 ♖xf7! and 40 ♗g2? in favor of 40 e4??.

Once again, a logical move is a blunder. After 40...♕h4! White was getting mated.

So which move was decisive?

It wasn’t 36...♖c2??, because White responded with 37 ♗xd5??.

It wasn’t 37...♗g6?? because the outcome was still in some doubt.

No, only the last blunder, 40 e4??, would be called unlucky.

Chess can be a game of swift and fatal changes. Positions are turned from losing to winning in a move or two. You can deplore the changes as unfair. They often are. But if you want to live in the real world of chess luck you need to take advantage of it. That is what this book is about.

Quiz

There will be quiz positions at the end of each chapter. Solutions on pages 235-240.

1.

Le Quang Liem – Caruana

St. Louis 2017

White to play

White should lose regardless of how he captures on g7. Why did he pick 50 ♖dxg7 ?

2.

Jakovenko – Grischuk

Khanty-Mansiysk 2009

Black to play

The final moves were 56...♖a1 57 ♔d2 ♖a2+ 58 ♔d1 ♖f2 59 ♗d2 ♖f5 60 ♗e1 ♖d5 61 ♔d2 ♖d4 62 ♖g3+ ♔f1 63 ♔e3 ♖d5 64 ♗f2 resigns.

How many of these moves were blunders?

3.

Nakamura – Carlsen

St. Louis 2017

White to play

And which, if any, of these moves were blunders? – 88 ♔b1 ♖d2 89 ♗xg1 ♖d1+ 90 ♔b2 e1(♕) 91 ♖xe1 ♖xe1 92 ♗b6 draw.

Chapter Two:

Swindle-Think

Frank Marshall didn’t invent swindling. But he made it his trademark, even naming the first collection of his games “Marshall’s Chess Swindles.”

What Marshall appreciated better than his contemporaries is that in bad positions there are fundamentally different criteria for choosing moves. The standards that we usually trust to point us towards the most successful moves often do not apply.

Marshall – Gruenfeld

Moscow 1925

1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 ♘c6 3 ♘c3 ♘f6 4 ♗b5 ♘d4 5 ♗c4 ♗c5 6 d3 d6 7 ♘a4 ♗b6 8 ♘xb6 ♘xf3+ 9 gxf3!? axb6 10 ♖g1 0-0 11 ♗g5 ♗e6 12 ♕d2 ♔h8 13 ♗h4?

Black to play

Marshall has been seeking play on the g-file since 9 gxf3. His last move prepares a typical Marshall sacrifice, 14 0-0-0 followed by 15 ♖xg7! ♔xg7 15 ♕g5+ ♔h8 16 ♕xf6+ and mates.

But he overlooked 13...♘xe4!. It is based on 14 ♗xd8 ♘xd2, when Black emerges with an extra pawn or more (15 ♔xd2 ♖fxd8 or 15 ♗xc7? ♘xf3+).

If he was looking to minimize Black’s advantage Marshall would have found 14 ♕h6!, the “computer-best” move and also a clever one. It damages Black’s pawn structure by forcing 14...gxh6, so that 15 ♗xd8 ♖fxd8 16 fxe4 gives him a fighting chance in the endgame.

Marshall wasn’t interested in hours of dogged and perhaps doomed defense. He raised the ante with a second pawn, 14 fxe4? ♕xh4 15 ♕c3 ♕xh2.

White to play

Nor was he inclined to the computer-best 15 ♕g5 ♕xg5 16 ♖xg5.

He chose 16 0-0-0 and then came 16...♗xc4 17 ♕xc4.

Black could have safely grabbed a third pawn (17...♕xf2). But two pawns is enough to win any foreseeable endgame – and an endgame seemed to be coming soon, thanks to his next moves, 17...♕h6+ 18 ♔b1 ♕e6!.

But there was no way Marshall was going to accommodate him with 19 ♕xe6?. He has been seeing things differently since move 14.

White to play

He stopped trying to just minimize Black’s advantage, the way a computer would. Instead, he began thinking like a swindler.

He looked for tactical chances. But after 19 ♕xc7 it seemed clear that Black had all the possible checks and dangerous moves, beginning with 19...♕xa2+ 20 ♔c1.

Marshall understood that when a player has the kind of material advantage that Black enjoys here, he is not likely to look for sacrifices. (The game might have been over before move 30 if Black had found 20...♖fc8 21 ♕xb6 ♖c6 22 ♕xb7 ♖cc8! and ...♖cb8.)

Much more likely is what happened, 20...♕a1+ 21 ♔d2.

Black to play

Believe it or not, this is the kind of position Marshall had been seeking since 14 fxe4. For the first time since then he has tactical chances.

For example, 21...♕a5+ 22 ♔e2! would tempt Black to take another pawn, 22...♖ac8 23 ♕e7 ♖xc2+.

But after 24 ♔f3 there are no more checks and Black’s f8-rook is hanging. He would be mated after 24...♔g8? 25 ♖xg7+! ♔xg7 26 ♖g1+.

The same ♖xg7! tactic works after 24...♕a8 25 ♖xg7! when Black has to try for a draw with 25...♕d8!.

Even the apparent safety-move, 24...♖g8, only draws after 25 ♖xg7!. For example, 25...♖xg7! 26 ♕d8+ ♖g8 27 ♕f6+ ♖g7 28 ♕d8+.

Black may or may not have seen all this. But after 21...♕xb2 he was shocked by – you guessed it – 22 ♖xg7! one more time.

Black to play

This time 22...♔xg7? loses, to 23 ♖g1+ and 24 ♕e7!.

It is too late to offer a queen trade, 22...♕b4+ 23 ♔e2 ♕c5, because 24 ♕e7 assures a draw.

But you can bet that Marshall would have played 24 ♖h1! instead. It threatens 25 ♖hxh7 mate. It’s the best move because it requires Black to find a defense that is not so obvious, 24...♔xg7 25 ♕e7! h6!. Then 26 ♖g1+ ♔h7 27 ♕f6 draws.

In any case, Black played the move that looked crushing, 22...♖ac8.

Then the star move in other variations, 23 ♕e7, loses to 23...♖xc2+ 24 ♔e1 ♖e2+ 25 ♖f2+ 26 ♔g1 ♔xg7.

But Marshall had perpetual check with 23 ♖xh7+! ♔xh7 24 ♖h1+. The rest was 24...♔g6 25 ♖g1+ ♔h6 26 ♖h1+ ♔g6 27 ♖g1+ draw.

If the king tries to advance to f4 it allows a deadly queen check (25...♔h5 26 ♖h1+ ♔g4?? 27 ♕d7+! or 25...♔h6 26 ♖h1+ ♔g5?? 27 ♕e7+).

Black’s final mistake was 21...♕xb2. What was his first? Ironically, it was the cautious 17...♕h6+/18...♕e6 – and the assumption that White would play his “best” available moves.

Computers confirm that 19 ♕c7! was not just a crazy Marshall move. It was the best move available.

And, as often happens in a great swindle, there were less detectable mistakes. Black could have won with 21…♕a5+ 22 ♔e2 ♕c5.

Computer versus Coffeehouse

Today we regard computers as the ultimate chess authorities. We check our opinion of the move we want to play with an engine’s evaluation. We feel good when our choice is rated number one by the machine. If our move isn’t rated the best, we try to figure out why not.

But often the move most likely to succeed against a human is not the move a computer strongly recommends. One game in particular made this difference known.

Duchess – Kaissa

World Computer Championship 1977

White to play

In a battle of two of the strongest engines of the day, White played 34 ♕a8+. Black replied 34...♖e8 and lost, of course, following 35 ♕xe8+.

The spectators – who included former world champion Mikhail Botvinnik – were stunned. Botvinnik helped create Kaissa. Why, he wondered, did it put a rook en prise? Obviously, 34...♔g7 was the right move, wasn’t it?

No, it was the second worst move (after 34...♕d8??). The reason is that White could have answered 34...♔g7 with 35 ♕f8+! ♔xf8 36 ♗h6+ and mate with ♖c8+.

In contrast, 34...♖e8 prolonged the game. It lasted until move 48 when it was adjudicated a win for White.

This is the problem that players face in the 21st century when they get a bad position. If they think like computers and play the “computer-best” moves they will last longer – provided they are playing computers.

But if their opponent is a human, they should think differently. Against a human, the only move to consider is 34...♔g7. A fallible White might not see 35 ♕f8+. Both moves should lose. But one offers a chance not to.

Least Worst

Computers don’t see the significance of that difference. Their algorithms are calibrated to find the least-worst move in a lost position. A move that keeps a Black disadvantage at +5.00 – the equivalent of an extra rook – must be better than one that allows a disadvantage of +6.00. Computers like minimizing moves.

Good swindlers see no benefit in minimizing. Rather than endure a hopeless position an additional ten, twenty or thirty moves, they will go for the move that offers some hope.

Jimenez – Larsen

Palma de Mallorca 1971