Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

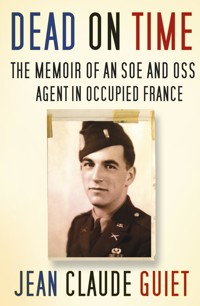

Jean Claude Guiet, born in France and raised in the US, attended Harvard aged 18 until, as a 'naïve' 19-year-old, he entered the US Army in 1943. As a native French speaker he was quickly assigned to SOE and the OSS (the precursor of the CIA) and parachuted into occupied France in the lead up to D-Day. After the liberation of Paris he was sent to Indochina to organise and train tribes in the jungles of the Far East to fight the Japanese. Subsequently he worked for the CIA in Washington. Told with characteristic understatement and charm, Jean Claude's writing perfectly captures the variety of his own long and fascinating life. Much more than one man's memoirs, Dead on Time is a tribute to a unique generation whose lives were regularly filled with both danger and laughter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 361

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am deeply indebted to my agent, Mark H. Yeats, for his practical guidance and his vast knowledge of and passion for all things SOE/OSS. His remarkable patience and professionalism was evident at every step of the process. He recognised my father’s memoir as a story that needed to be told and made it all possible.

I thank my editor, Chrissy McMorris at The History Press, who brought this endeavour to fruition with intelligence and sensitivity.

My deepest appreciation to Tania Szabó for writing her very thoughtful foreword to this book, for referring me to her agent Mark Yeats and for her kind support.

I am also very grateful to Robert Maloubier for his amazing foreword and for sharing experiences that illuminate my father as a young man.

I owe a great deal to Julie and Ron La Point for their deep personal interest in my father’s story and their assistance to him with word processing. My father referred to his computer as ‘that damned infernal machine’.

I am also thankful to Robert Forte, who has a great knowledge of the wireless radio that my father used and strongly supported the publication of this memoir.

CONTENTS

TITLE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FOREWORD BY ROBERT MALOUBIER

FOREWORD BY TANIA SZABÓ

FOREWORD BY CLAUDIA ALICE HOLZER

PREFACE BY JEAN CLAUDE GUIET

DEAD ON TIME: THE MEMOIR

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

POSTSCRIPTS

AFTERWORD BY CLAUDIA ALICE HOLZER

PLATES

COPYRIGHT

FOREWORD BYROBERT MALOUBIER

One day in May 1944, in London, our boss Major Charles Staunton told Violette Szabó, the ‘courier’ of our team, and myself:

The radio operator who is going to join us is a very young American, born of French parents, a tenderfoot, named Jean Claude Guiet. An OSS issue, he has been trained in the States. They have Special Training Schools similar to ours in the UK, you know. I suggest we have lunch together at Rose, the French restaurant in Soho, tomorrow. You know the place, don’t you?

Charles is the boss of our Special Operations Executive (SOE) team, ‘Salesman’. He has been on three secret assignments in occupied France. Captured by Vichy police in 1941, he had managed to escape across the Pyrénées to Spain, Portugal and back to England. A former international press correspondent, he is shrewd. The perfect boss and spiritual father for a youngster like me. I spent seven months as a saboteur under his command behind Normandy’s Atlantic Wall in 1943. We were flown back to the UK in February aboard a small plane of SOE’s Moonlight Squadron.

Rose is a typical bistro of Soho, a cosmopolitan district of London. A sort of narrow corridor invaded by kitchen smokes. Crude marble tables, thick earthenware plates. Nonetheless, Rose provides thick juicy steaks, and buckets of crisp chips. The bistro is unlicensed, so guests go and get their fill of thick red wine next door, at the York Minster, Dean Street’s famed French pub. His landlord, the Belgian Victor Berlemont, boasts London’s widest moustache: ‘ten inches from wing tip to wing tip’!

Jean Claude Guiet is dead on time. Impeccably clad in officer’s ‘pinks’, tall, sporty, handsome. Open face, frank grey eyes.

Violette whispers in my ear, ‘A good looker, isn’t he?’

Jean Claude sips his wine bravely, keeps wolfing his steak down. Mischievously, Violette stops him short. ‘It’s horse meat, you know! In the UK, meat is rationed, meat of all origins, but horse meat …’ Knowing how Yanks revere their horses, ‘the noblest conquest of men’, she expected him to choke. The lad is unruffled.

‘So, welcome to the club,’ says Violette. ‘Now tell us more about yourself.’

Jean Claude was born in the Jura region of France, close to the Swiss border. His parents, both professors, settled later in the United States. In June 1940, he was holidaying in France with his elder brother when both were nearly caught by the Germans who had invaded the country. They managed to reach Spain, Portugal and thereafter board a New York-bound steamship. He was approaching graduation from Harvard when Hirohito hit Pearl Harbor. He decided to join the armed forces. There a talent scout noted that he spoke perfect French. The OSS took over. At Camp X, he qualified as a potential secret agent to infiltrate occupied France and was transferred to SOE’s ‘Baker Street Irregulars’.

‘From now on, you’re one of ours,’ Violette tells him.

Bi-national, born of a French mother and an English father, ‘Vi’ is a 23-year-old war widow, and the mother of 2-year-old Tania, who often babbles at her side. Her husband, a French legionnaire, had been killed at El Alamein. He had never set eyes on his daughter. Violette had conceived an irrepressible hatred for the Germans who had killed ‘the man of her life’. She had joined the Forces. Spotted as multilingual, she had been ‘invited’ to join SOE’s French Section.

We are members of a team just as close-knit as a bomber crew, going to the cinema together, spending dinner-and-dance evenings at our favourite Knightsbridge Studio Club, playing poker or pontoon – a variation on Black Jack – at Wimpole Street’s SOE ‘hostel’.

We were to parachute early June into a communist maquis group in Limousin, central France. Staunton was to assess its fighting strength, its will to fight and see that it was properly supplied with weapons and equipment to be dropped from England. I was to train its men in guerrilla warfare, lead groups of them to road and rail ambushes, organise air drops and sabotage roads and railroads. Jean Claude was to be in charge of radio transmissions, Vi was to liaise with nearby SOE networks.

In early June 1944 we made for Hazells Hall, a stately Edwardian manor nested in a huge and elegant park in Cambridgeshire, one of the French Section ‘departing stations’. We made two or three aborted attempts. On the eve of 6 June, our B-24 four-engine Liberator bomber took off for good. We played poker throughout the three- or four-hour flight to Limoges. Alas, above our assigned dropping zone, the captain came to us: ‘Sorry, lady and gentlemen. The reception committee that was to welcome you is missing. See for yourself: no lights on the ground! My orders are clear: I am not to drop you blind! Here we go, back to UK …’

Using our ’chutes as a pillow, we lay down on the bomb compartment floor and fell asleep. From time to time I woke up, paid a visit to the cockpit, had a chat with the crew, looked out to dense cloud. Through gaps in the thick clouds one could see a foamy sea ripped by ship’s wakes. I wondered loudly, ‘What are they?’

‘Well, ships’ wakes mean that a convoy is passing by across the Channel,’ replied the captain. ‘That’s all.’

Past dawn we touched down at Tempsford, our Moonlight Squadron airbase. A car took us back to Hazells Hall. A few minutes later, we were fast asleep.

Around noon a hullaballoo woke me up. The bar was seemingly going wild with merrymakers bursting with laughter, crying out with joy, yelling and singing their heads off as if they had been drinking the night through. The beaming batman who brought a cup of tea a few minutes later spelt the news: ‘It’s D Day gentlemen. “We” have landed this morning!’

So that explained why the Channel was rippled by the wakes of a convoy, one amounting to 5,000 vessels landing 140,000 men on the beaches of Normandy!

We parachuted on the night of 7 June. Jean Claude tapped a safe arrival message out to London.

Two days later, disaster struck: Violette, sent by Staunton to liaise with the head of a nearby SOE network, ran into the vanguard of the ravenous SS Panzer Division Das Reich, which had been ordered by Rommel to leave its station in southern France and help contain Normandy’s beachhead. She was captured. We were never to see her again.

Though we were grieving, there was a war to be won. So Jean Claude went on dispatching hundreds of messages and eventually joined me in ambushing enemy convoys. Months later, Limoges’ German garrison surrendered. We drove to Paris. Jean Claude was most welcome at my family’s home in Neuilly, a northwestern suburb of Paris. Soon after, he was called back to the States.

I enlisted with Force 136, SOE’s Far East branch and was posted to Calcutta. Jean Claude joined a similar section of the OSS, based in Kunming, China. We managed, I don’t know how, to exchange letters across the Himalayas. In one of these he humorously described the mess that was the so-called ‘indomitable’ Chinese army. Alas, the letter was scrutinised by OSS censorship and poor Jean Claude was to be tried by a court martial for defaming America’s Great Ally! By a stroke of luck – thanks to Japan’s surrender! – the court martial was suspended and Jean Claude was discharged from the army and set free to resume his studies at Harvard.

Thereafter we lost sight of each other for nearly forty years, until a resident of Wormelow, a village near Hereford where Vi had spent some holidays, founded a museum dedicated to her. The event being highly publicised, Jean Claude and I were invited to attend. After a forty-year gap, the ‘youngster’ had not changed much. Hair thinning, but not an extra pound of fat on him. His straightforward look and sense of humour were still there. It was a happy reunion. Later we met again in Paris and Lons-le-Saunier, where he had a family home.

Thanks to his memoirs, anyone can now learn about the adventures of an American ‘tenderfoot’ fighting for the liberation of France and getting through, all smiles.

Thank you, Jean Claude!

Bob Maloubier

FOREWORD BYTANIA SZABÓ

Jean Claude Guiet, half-French, half-American, was a quiet man, self-contained and a tower of strength within a medium frame. He had proved his supreme suitability to be an SOE operative. On the occasions that I met him I was struck by his stillness, quickness and understanding of tight security – characteristics essential to the war-time wireless operator.

He tells his story without arrogance and self-aggrandisement – it is a simple tale of a simple man who accomplished his tasks superbly well under the most dangerous of circumstances. His irritation at lack of security, or transmissions that were far too long – and thus perilous – was well known.

He was born, educated and lived in France as a youngster and then in the US. This background was perfect for the tasks set him not only during those war years but in the post-war years until his retirement, where he sought excitement his own way, but always in control with his outwardly reserved and instinctively careful nature.

He admired and was somewhat smitten by Violette Szabó GC, CdeG*, my mother and fellow SOE agent, when they met in London to prepare for their June 1944 mission in the Haute Vienne, ‘Salesman II’. His team, made up of Philippe Liewer aka Major Charles Staunton, Bob Maloubier aka Bob Mortier and Violette aka Louise, were quartered in Sussac while Jean Claude remained alone and concealed in a small rural house near a watermill with his wireless equipment. Violette was captured after a gunfight with an advance unit of the Panzer Division Das Reich, ‘Der Führer’, so it fell to Jean Claude to send and receive ‘a flurry of transmissions concerning her capture’ under very dangerous circumstances.

It was very much my pleasure and honour to have met him and spoken with him. With great kindness he wrote the introduction to the 2007 hardback edition of Young, Brave and Beautiful, my account of Violette’s two missions of 1944, in the second of which Jean Claude played such an important role.

Violette was clearly drawn to him as, pushing her bike, she accompanied him to his little house while they chatted about their mission and got to know one another. So, thank you from the heart, Claude, for providing a sense of stability and thoughtfulness to Violette on the eve of that fateful day.

Tania Szabó

FOREWORD BYCLAUDIA ALICE HOLZER

Jean Claude Guiet’s parents, René Georges Guiet and Jeanne Zelie Seigneur, were married on 26 May 1920 in Urbana, Illinois. His parents both took guest professorships in French at the University of Illinois in Urbana in 1921. Jean Claude’s older brother, Pierre, was born in Urbana the same year. In 1923, the family returned to Belfort, France, where Jean Claude was born on 24 March 1924. In 1925, the family immigrated to the US and settled in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Jean Claude’s father, René, had been born in Laval, France, in 1896. He was a graduate of the French military college at Saint-Cyr and served in the First World War, earning the Croix de Guerre for exceptional conduct. He also received a Bachelor’s and PhD from the Sorbonne. His doctoral thesis dealt with opera libretti in France from Gluck to the French Revolution. He taught at the University of Illinois and Hunter College before joining the faculty at Smith College in 1926. Smith College is one of the so-called Seven Sisters, seven highly ranked colleges for women comparable to the Ivy League colleges. René was a well-respected professor emeritus of French language and literature and Chairman of the French Department for decades. He was an accomplished violinist and played in the Smith College orchestra. As a child, Jean Claude also played the violin.

Jean Claude’s mother, Jeanne, was born in Mandeure, western France in 1896. She was a respected assistant professor emeritus of French, also at Smith College. She was a master gardener and worked tirelessly on her flower beds. She also was a legendary hostess who employed an excellent chef, who happened to be her sister, Claire Seigneur.

In 1926, Jean Claude’s parents bought a beautiful house that had been built in 1857 at 70 Washington Avenue. It had extensive gardens which were Jeanne’s pride and joy. Jean Claude’s parents entertained with lavish formal dinner parties in the best French tradition. Their house was furnished with gorgeous French and American antiques, and oriental rugs of the finest quality graced their floors. It was truly exquisite. This is the world in which Jean Claude spent most of his childhood, except for summers in France. Jeanne demanded that only French be spoken at home.

Jean Claude’s childhood was sheltered and culturally very different from the informal American ways, which made him feel out of the norm. René was distant and intellectual. He believed that children should be seen and not heard. Jeanne was domineering, difficult, demanding and tough. To her, appearances were of paramount importance and she gleaned much pleasure from the beautiful objects surrounding her, much more than from people. She was emotionally distant and Jean Claude worked hard to please her, even though it was clear that Pierre was her favourite. Sadly, trying to please his mother was a driving force through much of his life. He had a close relationship with Pierre, his older brother and his only playmate. It is no wonder that, by his own admission, his overly sheltered childhood ‘resulted in a weak development of self-confidence’. He was timid and nervous in interactions outside his family and had an astounding lack of knowledge of the world around him.

Thankfully for Jean Claude, the family summered in France in the Jura village of Conliège. The woman Jean Claude referred to as his Grandmama, Marte Beley, was grandmother in name only, but he loved her very much and she was a wonderful influence on him. Jean Claude had a close connection to her and he truly enjoyed his summers with her. She allowed him to be a boy, to get his clothes dirty and to play and laugh. He worked alongside the farmers, learning how to harvest hay and a variety of other chores such as churning butter, making cheese, killing and plucking chickens, chopping wood and building fences from tree branches. Jean Claude’s mother was not pleased that he was acting like a ‘peasant’, but his Grandmama prevailed saying that she needed these chores to be done, thus liberating Jean Claude from his mother for a few short months. He loved to ride his bicycle and explore the countryside in complete freedom. Working the land remained a pleasure in Jean Claude’s life.

In the summer of 1939, only Pierre and Jean Claude made the trip to France. With Hitler threatening invasion, they spent an unsettled summer helping their Grandmama stock up on provisions. Pierre had a US passport since he was born there. But being the son of two French citizens made him a French citizen too. He had also turned 18 the previous February. Under French law, that made him eligible for the French army draft. Jean Claude was not affected since he was too young. René and Jeanne tried to straighten out the situation from the US, but realised that it would take time. Stuck in France, Pierre and Jean Claude were enrolled in the lycée in Lons-le-Saunier. Finally, Pierre received a French passport and a travel visa to Spain. They managed to flee to Lisbon, and in September 1940, they sailed on the ship Excalibur to New Jersey, where their parents met them.

The family spent that night with Tante Margot (Jeanne’s sister) and Oncle Lorenzo Marchini, who had a lovely apartment in New York City. Jean Claude had a good relationship with Margot and Lorenzo and he stayed with them whenever he was in town. The family returned to Northampton, Massachusetts, and Jean Claude attended Deerfield Academy for the next two and a half years. He entered Harvard University in 1942 but was immature and did little work in his first year. He lived in Dunster House and recalled lining up peas on the end of a knife and flicking them at some unsuspecting housemate. Maturity would come later! It was a relief to him when he received his draft notice since he was worried he was about to be kicked out of Harvard for low grades. He entered the US Army in June of 1943. Aged 19, he was an immature, naïve, privileged and innocent young man. He had completed most of his basic training when it was ‘discovered’ that he was French-born and a native French speaker. As a result, he was evaluated and assigned to SOE/OSS. He took his training seriously but admitted that the non-regimented life in SOE/OSS was much more to his liking than the highly organised regular military. His training and war-time experiences shaped the man he would become. He developed a strong sense of duty and responsibility. When he was discharged, he was much more ready and capable of dealing with the realities of civilian life.

Claudia Holzer

PREFACE BYJEAN CLAUDE GUIET

On my seventieth birthday I received a computer. My experience with them had been limited to studying the output of mainframe units, and the reality of hands-on working with one was an entirely new and frustrating experience. With the help of my children and grandchildren, as well as Word for Dummies, I have managed to master enough of the operational complexities to feel sufficiently competent to try writing. Naturally, at my age, when one reaches what Disraeli called one’s anecdotage, the first thing that one feels comfortable with is one’s memoirs.

The fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, with its heightened interest in that conflict, motivated a long-dormant realisation that I should perhaps relate my experiences during the war (not that they represented anything much out of the ordinary from the myriad activities that occurred throughout it). Indeed, my experiences are of interest in part because of the popularity and hype of James Bond Syndrome and the fact that I was involved in an operation in which the outstanding importance was the actions and fate of our courier, one of three women who were the only agents in the Secret Operations Executive (SOE) to have been awarded the George Cross. For me, the importance and particular personal interest lies in the operation’s relative ease, enjoyment and lack of contention compared to the norm for that war. Ben Bradlee summarised one aspect of it perfectly in his 1995 book A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures: the war had been ‘more exciting, more meaningful than anything I’d ever done. This is why I had such a wonderful time in the war. I just plain loved it. Loved the excitement, even loved being a little bit scared. Loved the sense of achievement, even if it was only getting from Point A to Point B, loved the camaraderie.’

Right after my discharge in November 1945, until the reality of the needs of starting civilian life took over, I had toyed with the idea of writing a memoir of my adventures. In the short time before returning to college, I had even filled an exam book with notes that might serve as an aide-mémoire. Rediscovery of that exam book, which had survived many moves, contributed greatly to my decision to go ahead with the project even though its data often turned out to be incomplete because I had too often omitted dates, names and place names, probably on the assumption they would never be forgotten. Yet the sequence of events was still there and the few details that were recorded helped jog my memory on to many more memories, reinforcing the realisation that many details would be more difficult to recall or trace the longer I waited. There are still many specifics and fairly important events about which I have no clear memory other than the fact they happened.

I have undertaken this effort somewhat as a challenge and for my personal satisfaction with, perhaps, an undercurrent of recording my experiences for family posterity should anyone be interested. I may well have had the desire to add my ‘two cents’ worth’ to the war tales of the early post-war period and current fiftieth anniversary though, in fact, most seemed to be more moving and interesting than mine, as were many of the accounts I have heard from other veterans. From all of these sources I realised that my army experiences, combat and other, had none of the regimented group discipline of the regular combat units or the extended exposure to the many horrors – weather, tedium, fatigue, exhaustion, and all the other battle dangers – of participants in the Pacific operations, the Italian campaign, D-Day or the Ardennes. I can only invoke and apply the view of Teddy Roosevelt: I had a relatively ‘lovely little war’.

DEAD ON TIMETHE MEMOIR

CHAPTER 1

My introduction to the war came well before my direct involvement in it, when my brother Pierre, three years my senior, and I happened to be in France when war was declared on 3 September 1939. As we quite regularly had done in previous years, we had come over in June on the Normandie. For the first time we had made the trip alone without our parents, a major event in itself in our lives. I was fifteen with no experience of life outside a protective first-generation French family. My brother, at least, had experienced being away from home at school.

We spent a pleasant early summer in the Jura with our grandmother in her large house and garden in a small farming village where the cows followed a cowherd out in the morning and returned with him in the evening. Each cow returned on its own into its stable. The milk was taken straight to a cooperative and sold retail as well as wholesale immediately, refrigeration being non-existent. It was a daily meeting place. Other than dairy and some agriculture, the vineyards and winemaking were the primary village activity. It was a peaceful existence with weekly trips to the nearest city for the weekly Thursday marché.

As war became imminent we ran into our first difficulties when we went to Lyon to get the necessary visas for the return to America. Being fifteen I had no problem at all obtaining an exit visa on my French passport: Pierre, however, though born of French parents in Urbana, Illinois, and therefore an American citizen by birth, could not obtain a French exit visa on his US passport. By French law, being born of French parents he was French and, being eighteen, he was eligible for the draft. It was reluctantly decided after much correspondence that we would remain in France and attend the lycée while our parents worked on the problem and pulled strings from the United States. In retrospect, a great deal of faith was obviously being placed in the reputation of the French army.

We spent a difficult six months in the very unfamiliar environment of the French educational system, where in almost every subject our classmates were way ahead of us. My two years of Latin (translation of Latin to English) were faced with their four years (translation of Latin to French and French to Latin); they were starting a third year of geometry and a first year of algebra versus my one year of algebra and no geometry; while I could speak and read French fluently, I had no experience in writing it, and in the twice weekly dictée my fellow students’ neatness (underlining the title twice without crossing any part of a letter that projected below the line, and accomplishing the entire dictation accurately in ink without corrections) was beyond me. Never did I miss pencil and eraser so much.

The exit visa problem was finally resolved early in the spring on the advice of a family friend. It was a simple, if somewhat irregular solution, and perhaps typical of a country that came up with the adage that laws are made to be bypassed. Pierre was to obtain a French passport from a different Prefecture without making any mention of the US passport. It was astonishingly simple in those pre-computer days, and in late April he had a French passport with an exit visa to visit Spain with no more than an admonition to keep in contact for possible call up. Since there were no other visas on this French passport he was, it was thought, limited to travel in Spain. Our plans were obviously quite different: once into Spain, Pierre would destroy his French passport and proceed under the American passport. By April everything seemed to be in place and just before the beginning of the debacle, Mother had made boat reservations for us, but events overtook us.

There was a growing uncertainty that all was well and we had felt somewhat uncomfortable with the apparent hesitancy on both sides of what came to be called ‘the phony war’. The photo in Life magazineshowing a French soldier on guard sitting on a chair with his feet in slippers in front of one of the fortress doors in the rear of the Maginot Line (in retrospect) epitomized the situation. Throughout that winter we had wondered, as did many others, what was really happening. Listening to French radio broadcasts, which began with eight catchy notes from Auf der Luneburger Heide, did little to enlighten us. Pervasive among the population was a considerable apathy, almost passivity, and not much confidence in official government war communiqués.

We continued to ride our bikes every day except Sunday, cycling the five kilometers to the lycée in Lons-le-Saunier, past the barracks where the Moroccan troops seemed to do nothing but stand around, and our only other contact with the reality of the war occurred when several companies of reservists were quartered in our village and in our garage with a mobile field kitchen in back in a courtyard. The soldiers slept on straw and hay and used their overcoats for blankets. Their equipment was old, 1918 Lebel rifles with long, thin bayonets that looked more like fencing foils than lethal weapons, and they left them lying casually about. They, too, wandered about the village with bits of straw and hay on their uniforms doing nothing during the two weeks of their stay and, while we enjoyed watching the preparation and distribution of the meals in the mobile field kitchen, even our youthful enthusiasm did not succeed in impressing us with any of the ‘military might’ we were witnessing. Our only participative war effort involved us in an informal group keeping an ineffective and disorganized lookout for enemy paratroopers (for which the French army provided us with cigarettes). It was with this encouragement that as a teenager wanting to act adult I started to smoke in earnest.

The reality of the situation (which we had seriously begun to suspect with the change in command from General Gamelin to General Weygand) became a strong, almost impossible-to-deny certainty by the middle of May, when the first refugees started passing through town. It really hit home hard on 13 June, when we were all abruptly, and with no specific explanation, sent home from school and told the lycée would be closed until further notice. The very next day some distant cousins, who were being relocated by the Peugeot factory to near Saint-Étienne in central France, stopped by and brought with them a sense of urgency and fear. We started to get the old Renault ready and agreed to take our neighbor’s son Dédé (who was a little younger than I) and daughter Mimi (who was probably seventeen) with us. This made five of us with grandmother, who kept insisting she was responsible for us and had to come.

At about 4:00 a.m. on the fifteenth we were awakened by tremendous detonations which rattled the windows. With a sense of adventure, Pierre and I hastened cautiously to town on our bikes to find out what was happening. The gasoline storage tanks in Lons had been blown up to keep them from the Germans. The town was in pandemonium; the narrow streets were noisy and more crowded than on market day with an excited melee of evacuees from the north trying to get through and locals getting ready to leave. Military vehicles of all sorts added to the confusion. In a very short time there was near gridlock.

We hurried home appalled, and it was quickly decided that it was time we should leave. I cannot remember any specific reasons why we made the decision, but excitement, stress and the element of public panic was obviously involved. It just seemed like the thing to do. We managed to strap two mattresses, blankets and suitcases on the roof of the car; stuffed food and sandwiches as well as two cans of gasoline in the small trunk; and left shortly after noon with no more specific destination in mind than heading south.

Our experience with gridlock in Lons that morning kept us on back roads, bypassing all big towns whenever possible. That afternoon we got south of Lyon and stopped at the edge of a wheat field to camp for the night. The farmer came down, worried that we might damage his field, but when he saw we were careful people he kindly offered to rent a room for the women and let the boys sleep on hay in a shed.

The next day we got through Saint-Étienne and into true refugee traffic. While the traffic north of Saint-Étienne had been acceptable thanks to the back roads, we were now limited to main roads through the very mountainous Massif Central. Overloaded cars and trucks struggled to crawl up the steep, curving road; radiators overheated, trucks overturned at sharp turns on the very concave Route Nationale, and there were frequent pileups caused by frantic drivers trying to get past anything they perceived as an obstacle delaying their progress. We finally reached Le Puy in the Haute Loire department, stressed, tired and somewhat shaken and wondering if we had done the right thing. We had been told by some northern refugees that we could find places to sleep there, but everything was full. We finally found a barn we could stay in, on our mattresses and the hay. We had planned to go further south, but spent the next day there, too, both because it was raining hard and because the radio was mentioning the possibility of an armistice and urging everyone to stay where they were. So we continued our search for housing.

Luckily, we found a place in a large farm outside the village of Sanssac l’Église. In addition to the barn, the outbuildings and the usual enormous manure pile, the farmhouse was a large two-story building that at one time had been a small manorial holding.

Immediately upon our arrival, even before showing us what she had to offer in terms of lodgings, the farmer’s wife invited us in for a snack (le gouté). We must have looked very much in need. As we entered the enormous kitchen, she shooed chickens off the table and pushed two sheep back outside. Poor grandmother, who was neat and clean to the point of extreme fastidiousness, was obviously disconcerted. The plates, however, were clean and the fresh, homemade wholewheat bread with unsalted butter that had been churned just that morning, homemade sausage, and cheese were deliciously satisfying, most welcome, and thoroughly enjoyed.

The room available for us was, like the kitchen, disconcerting. It was up a flight of worn stone stairs and had until very recently been used to store barley. Yet it was spacious and well lit by several large windows and had a closed-off fireplace from which hung a stovepipe. Through a small alcove there was an open balcony from which a large flooring stone had been removed. This was our bathroom, open to the elements, overlooking the back of the huge barn and three flights up due to the slope of the land. While the opening from the missing stone was too small to fall through, it was big enough to give the impression that it was a possibility. There was a definite impression of altitude and vertigo, not to mention complete visibility and the need to forego any shyness.

We borrowed brooms, swept up as well as we could, and brought up our bedding and luggage. The farmer’s wife insisted on loaning us an additional cornhusk mattress, a rickety table with two old chairs and some wooden boxes to sit on, a rusty two-burner wood stove (which luckily fitted the stovepipe), a few plates, glasses, and forks. One apparently was assumed to carry the locally ubiquitous multipurpose and seldom-washed pocketknife. Not wanting to appear demanding, we bought some knives in the village. We placed all three mattresses in a corner, all of us sleeping together in order to share the blankets.

The stovepipe determined the stove location and the table and chairs were placed near the stove, where they could be used for interim storage and food preparation. Despite our cleaning efforts, we still had rats rustling around at night, I was told (I never heard them in my sound sleep), and therefore we stored what little food we had not eaten in a box hung from a convenient hook in the ceiling. For the older ones, sleeping was difficult and fitful. Arrangements for washing up were more often than not quite awkward and involved, especially since we had to bring the water up from the pump by the dishpan full. It then had to be heated if we wanted warm water. It was, of course, dumped three stories down through the toilet with a satisfying splash.

For the approximate two weeks of our stay, the days and evenings were long. Every day, after housekeeping chores, some of us went into the village for basics like bread and, more importantly, information. However, we bought most of our food from the farm: eggs, butter, milk, fresh vegetables and an occasional chicken. With nothing to do during the day we volunteered to help with the haying. This activity differed from what I was accustomed to in that the hay was barely cured and was pitchforked green and sometimes even wet into the loft, where large quantities of salt were added to eliminate spontaneous combustion. We also helped in the hand-churning of the butter every other day. The reward for helping was the afternoon gouté, a filling high tea type of snack similar to the one we had enjoyed when we first arrived.

Evenings, however, were a trial with little to combat the boredom and only one weak light bulb hanging from the ceiling in the center of the room. There was no radio and nothing to read other than an occasional old newspaper. By dark we were all in bed. We did, nevertheless, appreciate that we were indeed well off. Pierre quite regularly went to the village because he did not particularly enjoy physical labor and made the best of the excuse that he went primarily to seek information. It turned out that he was very competent in that, and one day on his return from Le Puy, where he had gone on a borrowed bike, he excitedly announced, ‘We’re going home! I’ve found some gas. All we have to do is go pick it up.’

It seemed that restrictions on travel that had been in effect were being lifted, that an armistice had either been signed or was about to be signed, and that we had to have a rather large amount of cash for the gas he had located. The cash we managed (although it left us without much reserve), but the real problem was how to get the gas and the car in the same place; the Renault was on empty.

Again the farmer’s wife came to the rescue, selling us four bottles of home-brewed eau-de-vie which, with what little gas remained in the car, got it sputtering and without much power to the gasoline source, which, luckily, was not up any steep hills. With the tank and our two cans full, we returned to the farm, loaded everything up, and early the next morning (after thanking the farmer’s wife warmly and expressing the hope that her husband would soon be back from the army) we left. We made the return trip in one day, encountering little traffic and only the battered and burned out wrecks that had occurred on the way out.

We drove up the village street triumphantly honking the horn and discovered that not only were we the last of those who had left to have returned, but that we needn’t have left at all. Nothing had happened, Conliège was in the Non-Occupied Zone. Still, it was wonderful to be back!

July and early August were very busy for us. First we made contact with our parents in the US, who made several ship reservations for us out of Lisbon and forwarded money for both us and grandmother which we were able to pick up relatively safely and easily in Geneva. Since grandmother insisted on staying in France, we did our best to help her get ready for the winter and the unknown, unfinished war.

With the assistance of the farmers I had regularly helped with haying in previous summers, we hauled and cut several cords of wood; located and transported huge burlap bags of sawdust (which burned slowly in the stoves in lieu of coal, as we had discovered the past winter); went up to the plateau with hand carts to collect all the pine cones we could find; cut endless amounts of vineyard trimmings into kindling; made sauerkraut; dug two of the large boxwood-bordered lawn squares of the formal garden into future vegetable garden plots; built two more rabbit hutches; and laid in all the canned goods, sugar, and cooking oil we could locate. Finally, before mid-August, the time for departure had arrived. The time was guesstimated by how long it would take to reach Lisbon, all the more unsubstantiated since we were not certain what crossing the frontier into Spain would involve.

Our departure was undoubtedly more of an emotional strain on our grandmother than on us. While we were concerned about leaving her alone and nervous about whatever unknowns we might encounter, we had the optimism of youth and rather enjoyed the whole idea of this adventure. We left confidently on a beautiful, sunny market day for Lons, taking advantage of the little trolley that came down from Saint-Claude. We then took the train from Lons to Avignon. We each carried a small suitcase, having decided that suitcases better suited two young vacationers on their way to visit Spain than the rucksacks that many refugees seemed to carry. We also had a musette bag for food that contained mainly bread and cheese. I, who until then had shunned cheese as an inedible thing, would have to learn to like it; it was that or go hungry. We had originally planned to stay in Avignon, but the local train to Perpignan was immediately available and we jumped on board, reaching our destination early that evening. I remember the meal of eggplant, tomatoes, and garlic swimming in much strong olive oil we received in a small local restaurant. Perhaps I remember it because I had not eaten the bread and cheese we had with us and I was starving.

The next day we took a smaller ‘milk run’ local to the frontier town of Cerbère. It was crowded with an odd mix of passengers: locals getting on and off at every stop, gossiping in their strong southern French accents and intonations or arguing heatedly that if the vineyard owners did not kill a pig for the help, they could certainly expect to pick the grapes all by themselves (s’ils ne le tuent pas le cochon, ils peuvent bien se les cueillir les raisins); a few non-locals who were obviously French by their different accents, clothing, mannerisms and their rather restrained conversation limited to the members of their own group; and finally a group who were neither local nor French, individuals of all ages who sat in strained, tired silence.

We all got off as it was the end of the line (the rail gauge in Spain was wider than in France); the locals quickly and certain of their destinations, but the rest of us more slowly and hesitantly. We were among the last, and as we approached the entrance to the customs area we encountered some of our fellow non-local French passengers (who had preceded us) coming out, complaining despondently and indignantly among themselves that the frontier was closed.

While this was disconcerting for us, the stress and worry of the non-French travelers, whose comprehension of that announcement was uncertain, was quite manifest. Not trusting hearsay, we went into the customs area, received the same news from the only person there, but with the additional bit of information that things would be operating the next day with ‘damned visitors’ present. Until now we travelers had scarcely acknowledged each other’s existence, much less talked to one another, so we were somewhat taken aback on our way out when one of the non-French travelers asked in very halting, heavily-accented French what had been said. When we had finally succeeded in making ourselves understood, he shook his head sadly saying, ‘police allemande’ and left with two others.