5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: James Bond 007

- Sprache: Englisch

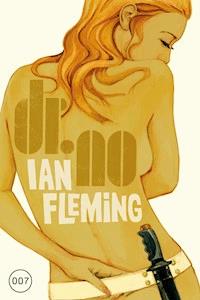

Meet James Bond, the world's most famous spy.Dispatched by M to investigate the mysterious disappearance of MI6's Jamaica station chief, Bond was expecting a holiday in the sun. But when he discovers a deadly centipede placed in his hotel room, the vacation is over.On this island, all suspicious activity leads inexorably to Dr. Julius No, a reclusive megalomaniac with steel pincers for hands. To find out what the good doctor is hiding, 007 must enlist the aid of local fisherman Quarrel and alluring beachcomber Honeychile Rider. Together they will combat a local legend the natives call "the Dragon," before Bond alone must face the most punishing test of all: an obstacle course - designed by the sadistic Dr. No himself that measures the limits of the human body's capacity for agony.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Dr. No

Dr. No

IAN FLEMING

Contents

1: Hear You Loud and Clear

2: Choice of Weapons

3: Holiday Task

4: Reception Committee

5: Facts and Figures

6: The Finger on the Trigger

7: Night Passage

8: The Elegant Venus

9: Close Shaves

10: Dragon Spoor

11: Amidst the Alien Cane

12: The Thing

13: Mink-Lined Prison

14: Come Into My Parlour

15: Pandora’s Box

16: Horizons of Agony

17: The Long Scream

18: Killing Ground

19: A Shower of Death

20: Slave-Time

01

Hear You Loud and Clear

Punctually at six o’clock the sun set with a last yellow flash behind the Blue Mountains, a wave of violet shadow poured down Richmond Road, and the crickets and tree frogs in the fine gardens began to zing and tinkle.

Apart from the background noise of the insects, the wide empty street was quiet. The wealthy owners of the big, withdrawn houses – the bank managers, company directors and top civil servants – had been home since five o’clock and they would be discussing the day with their wives or taking a shower and changing their clothes. In half an hour the street would come to life again with the cocktail traffic, but now this very superior half-mile of ‘Rich Road’, as it was known to the tradesmen of Kingston, held nothing but the suspense of an empty stage and the heavy perfume of night-scented jasmine.

Richmond Road is the ‘best’ road in all Jamaica. It is Jamaica’s Park Avenue, its Kensington Palace Gardens, its Avenue D’Iéna. The ‘best’ people live in its big old-fashioned houses, each in an acre or two of beautiful lawn set, too trimly, with the finest trees and flowers from the Botanical Gardens at Hope. The long, straight road is cool and quiet and withdrawn from the hot, vulgar sprawl of Kingston where its residents earn their money, and, on the other side of the T-intersection at its top, lie the grounds of King’s House, where the Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Jamaica lives with his family. In Jamaica, no road could have a finer ending.

On the eastern corner of the top intersection stands No. 1 Richmond Road, a substantial two-storey house with broad white-painted verandas running round both floors. From the road a gravel path leads up to the pillared entrance through wide lawns marked out with tennis courts on which this evening, as on all evenings, the sprinklers are at work. This mansion is the social Mecca of Kingston. It is Queen’s Club, which, for fifty years, has boasted the power and frequency of its blackballs.

Such stubborn retreats will not long survive in modern Jamaica. One day Queen’s Club will have its windows smashed and perhaps be burnt to the ground, but for the time being it is a useful place to find in a subtropical island – well run, well staffed and with the finest cuisine and cellar in the Caribbean.

At that time of day, on most evenings of the year, you would find the same four motor cars standing in the road outside the club. They were the cars belonging to the high bridge game that assembled punctually at five and played until around midnight. You could almost set your watch by these cars. They belonged, reading from the order in which they now stood against the kerb, to the Brigadier in command of the Caribbean Defence Force, to Kingston’s leading criminal lawyer and to the Mathematics Professor from Kingston University. At the tail of the line stood the black Sunbeam Alpine of Commander John Strangways, RN (Ret.), Regional Control Officer for the Caribbean – or, less discreetly, the local representative of the British Secret Service.

Just before six-fifteen, the silence of Richmond Road was softly broken. Three blind beggars came round the corner of the intersection and moved slowly down the pavement towards the four cars. They were Chigroes – Chinese Negroes – bulky men, but bowed as they shuffled along, tapping at the kerb with their white sticks. They walked in file. The first man, who wore blue glasses and could presumably see better than the others, walked in front holding a tin cup against the crook of the stick in his left hand. The right hand of the second man rested on his shoulder and the right hand of the third on the shoulder of the second. The eyes of the second and third men were shut. The three men were dressed in rags and wore dirty jippa-jappa baseball caps with long peaks. They said nothing and no noise came from them except the soft tapping of their sticks as they came slowly down the shadowed pavement towards the group of cars.

The three blind men would not have been incongruous in Kingston, where there are many diseased people on the streets, but, in this quiet rich empty street, they made an unpleasant impression. And it was odd that they should all be Chinese Negroes. This is not a common mixture of bloods.

In the cardroom, the sunburnt hand reached out into the green pool of the centre table and gathered up the four cards. There was a quiet snap as the trick went to join the rest. ‘Hundred honours,’ said Strangways, ‘and ninety below!’ He looked at his watch and stood up. ‘Back in twenty minutes. Your deal, Bill. Order some drinks. Usual for me. Don’t bother to cook a hand for me while I’m gone. I always spot them.’

Bill Templar, the Brigadier, laughed shortly. He pinged the bell by his side and raked the cards in towards him. He said, ‘Hurry up, blast you. You always let the cards go cold just as your partner’s in the money.’

Strangways was already out of the door. The three men sat back resignedly in their chairs. The coloured steward came in and they ordered drinks for themselves and a whisky and water for Strangways.

There was this maddening interruption every evening at six-fifteen, about halfway through their second rubber. At this time precisely, even if they were in the middle of a hand, Strangways had to go to his ‘office’ and ‘make a call’. It was a damned nuisance. But Strangways was a vital part of their four and they put up with it. It was never explained what ‘the call’ was, and no one asked. Strangways’s job was ‘hush’ and that was that. He was rarely away for more than twenty minutes and it was understood that he paid for his absence with a round of drinks.

The drinks came and the three men began to talk racing.

In fact, this was the most important moment in Strangways’s day – the time of his duty radio contact with the powerful transmitter on the roof of the building in Regent’s Park that is the headquarters of the Secret Service. Every day, at eighteen-thirty local time, unless he gave warning the day before that he would not be on the air – when he had business on one of the other islands in his territory, for instance, or was seriously ill – he would transmit his daily report and receive his orders. If he failed to come on the air precisely at six-thirty, there would be a second call, the ‘Blue’ call, at seven and, finally, the ‘Red’ call at seven-thirty. After this, if his transmitter remained silent, it was ‘Emergency’, and Section III, his controlling authority in London, would urgently get on the job of finding out what had happened to him.

Even a ‘Blue’ call means a bad mark for an agent unless his ‘Reasons in Writing’ are unanswerable. London’s radio schedules round the world are desperately tight and their minute disruption by even one extra call is a dangerous nuisance. Strangways had never suffered the ignominy of a ‘Blue’ call, let alone a ‘Red’, and was as certain as could be that he never would do so. Every evening, at precisely six-fifteen, he left Queen’s Club, got into his car and drove for ten minutes up into the foothills of the Blue Mountains to his neat bungalow with the fabulous view over Kingston harbour. At six twenty-five he walked through the hall to the office at the back. He unlocked the door and locked it again behind him. Miss Trueblood, who passed as his secretary, but was in fact his No. 2 and a former Chief Officer WRNS, would already be sitting in front of the dials inside the dummy filing cabinet. She would have the earphones on and would be making first contact, tapping out his call-sign, WXN, on fourteen megacycles. There would be a shorthand pad on her elegant knees. Strangways would drop into the chair beside her and pick up the other pair of headphones and, at exactly six twenty-eight, he would take over from her and wait for the sudden hollowness in the ether that meant that WWW in London was coming in to acknowledge.

It was an iron routine. Strangways was a man of iron routine. Unfortunately, strict patterns of behaviour can be deadly if they are read by an enemy.

Strangways, a tall lean man with a black patch over the right eye and the sort of aquiline good looks you associate with the bridge of a destroyer, walked quickly across the mahogany-panelled hallway of Queen’s Club and pushed through the light mosquito-wired doors and ran down the three steps to the path.

There was nothing very much on his mind except the sensual pleasure of the clean fresh evening air and the memory of the finesse that had given him his three spades. There was this case, of course, the case he was working on, a curious and complicated affair that M had rather nonchalantly tossed over the air at him two weeks earlier. But it was going well. A chance lead into the Chinese community had paid off. Some odd angles had come to light – for the present the merest shadows of angles – but if they jelled, thought Strangways as he strode down the gravel path and into Richmond Road, he might find himself involved in something very odd indeed.

Strangways shrugged his shoulders. Of course it wouldn’t turn out like that. The fantastic never materialised in his line of business. There would be some drab solution that had been embroidered by overheated imaginations and the usual hysteria of the Chinese.

Automatically, another part of Strangways’s mind took in the three blind men. They were tapping slowly towards him down the sidewalk. They were about twenty yards away. He calculated that they would pass him a second or two before he reached his car. Out of shame for his own health and gratitude for it, Strangways felt for a coin. He ran his thumbnail down its edge to make sure it was a florin and not a penny. He took it out. He was parallel with the beggars. How odd, they were all Chigroes! How very odd! Strangways’s hand went out. The coin clanged in the tin cup.

‘Bless you, Master,’ said the leading man. ‘Bless you,’ echoed the other two.

The car key was in Strangways’s hand. Vaguely he registered the moment of silence as the tapping of the white sticks ceased. It was too late.

As Strangways had passed the last man, all three had swivelled. The back two had fanned out a step to have a clear field of fire. Three revolvers, ungainly with their sausage-shaped silencers, whipped out of holsters concealed among the rags. With disciplined precision the three men aimed at different points down Strangways’s spine – one between the shoulders, one in the small of the back, one at the pelvis.

The three heavy coughs were almost one. Strangways’s body was hurled forward as if it had been kicked. It lay absolutely still in the small puff of dust from the sidewalk.

It was six-seventeen. With a squeal of tyres, a dingy motor hearse with black plumes flying from the four corners of its roof took the T-intersection into Richmond Road and shot down towards the group on the pavement. The three men had just had time to pick up Strangways’s body when the hearse slid to a stop abreast of them. The double doors at the back were open. So was the plain deal coffin inside. The three men manhandled the body through the doors and into the coffin. They climbed in. The lid was put on and the doors pulled shut. The three men sat down on three of the four little seats at the corners of the coffin and unhurriedly laid their white sticks beside them. Roomy black alpaca coats hung over the backs of the seats. They put the coats on over their rags. Then they took off their baseball caps and reached down to the floor and picked up black top hats and put them on their heads.

The driver, who also was a Chinese Negro, looked nervously over his shoulder.

‘Go, man. Go!’ said the biggest of the killers. He glanced down at the luminous dial of his wristwatch. It said six-twenty. Just three minutes for the job. Dead on time.

The hearse made a decorous U-turn and moved at a sedate speed up to the intersection. There it turned right and at thirty miles an hour it cruised genteelly up the tarmac highway towards the hills, its black plumes streaming the doleful signal of its burden and the three mourners sitting bolt upright with their arms crossed respectfully over their hearts.

‘WXN calling WWW . . . WXN calling WWW . . . WXN . . . WXN . . . WXN . . .’

The centre finger of Mary Trueblood’s right hand stabbed softly, elegantly, at the key. She lifted her left wrist. Six twenty-eight. He was a minute late. Mary Trueblood smiled at the thought of the little open Sunbeam tearing up the road towards her. Now, in a second, she would hear the quick step, then the key in the lock and he would be sitting beside her. There would be the apologetic smile as he reached for the earphones. ‘Sorry, Mary. Damned car wouldn’t start.’ Or, ‘You’d think the blasted police knew my number by now. Stopped me at Halfway Tree.’ Mary Trueblood took the second pair of earphones off their hook and put them on his chair to save him half a second.

‘WXN calling WWW . . . WXN calling WWW.’ She tuned the dial a hair’s breadth and tried again. Her watch said six twenty-nine. She began to worry. In a matter of seconds, London would be coming in. Suddenly she thought, God, what could she do if Strangways wasn’t on time! It was useless for her to acknowledge London and pretend she was him – useless and dangerous. Radio Security would be monitoring the call, as they monitored every call from an agent. Those instruments which measured the minute peculiarities in an operator’s ‘fist’ would at once detect it wasn’t Strangways at the key. Mary Trueblood had been shown the forest of dials in the quiet room on the top floor at headquarters, had watched as the dancing hands registered the weight of each pulse, the speed of each cipher group, the stumble over a particular letter. The Controller had explained it all to her when she had joined the Caribbean station five years before – how a buzzer would sound and the contact be automatically broken if the wrong operator had come on the air. It was the basic protection against a Secret Service transmitter falling into enemy hands. And, if an agent had been captured and was being forced to contact London under torture, he had only to add a few hair-breadth peculiarities to his usual ‘fist’ and they would tell the story of his capture as clearly as if he had announced it en clair.

Now it had come! Now she was hearing the hollowness in the ether that meant London was coming in. Mary Trueblood glanced at her watch. Six-thirty. Panic! But now, at last, there were the footsteps in the hall. Thank God! In a second he would come in. She must protect him! Desperately she decided to take a chance and keep the circuit open.

‘WWW calling WXN . . . WWW calling WXN . . . Can you hear me? . . . can you hear me?’ London was coming over strong, searching for the Jamaica station.

The footsteps were at the door.

Coolly, confidently, she tapped back: ‘Hear you loud and clear . . . Hear you loud and clear . . . Hear you . . .’

Behind her there was an explosion. Something hit her on the ankle. She looked down. It was the lock of the door.

Mary Trueblood swivelled sharply on her chair. A man stood in the doorway. It wasn’t Strangways. It was a big black man with yellowish skin and slanting eyes. There was a gun in his hand. It ended in a thick black cylinder.

Mary Trueblood opened her mouth to scream.

The man smiled broadly. Slowly, lovingly, he lifted the gun and shot her three times in and around the left breast.

The girl slumped sideways off her chair. The earphones slipped off her golden hair on to the floor. For perhaps a second the tiny chirrup of London sounded out into the room. Then it stopped. The buzzer at the Controller’s desk in Radio Security had signalled that something was wrong on WXN.

The killer walked out of the door. He came back carrying a box with a coloured label on it that said PRESTO FIRE, and a big sugar-sack marked TATE & LYLE. He put the box down on the floor and went to the body and roughly forced the sack over the head and down to the ankles. The feet stuck out. He bent them and crammed them in. He dragged the bulky sack out into the hall and came back. In the corner of the room the safe stood open, as he had been told it would, and the cipher books had been taken out and laid on the desk ready for work on the London signals. The man threw these and all the papers in the safe into the centre of the room. He tore down the curtains and added them to the pile. He topped it up with a couple of chairs. He opened the box of Presto firelighters and took out a handful and tucked them into the pile and lit them. Then he went out into the hall and lit similar bonfires in appropriate places. The tinder-dry furniture caught quickly and the flames began to lick up the panelling. The man went to the front door and opened it. Through the hibiscus hedge he could see the glint of the hearse. There was no noise except the zing of crickets and the soft tick-over of the car’s engine. Up and down the road there was no other sign of life. The man went back into the smoke-filled hall and easily shouldered the sack and came out again, leaving the door open to make a draught. He walked swiftly down the path to the road. The back doors of the hearse were open. He handed in the sack and watched the two men force it into the coffin on top of Strangways’s body. Then he climbed in and shut the doors and sat down and put on his top hat.

As the first flames showed in the upper windows of the bungalow, the hearse moved quietly from the sidewalk and went on its way up towards the Mona Reservoir. There the weighted coffin would slip down into its fifty-fathom grave and, in just forty-five minutes, the personnel and records of the Caribbean station of the Secret Service would have been utterly destroyed.

02

Choice of Weapons

Three weeks later, in London, March came in like a rattlesnake.

From first light on 1 March, hail and icy sleet, with a Force 8 gale behind them, lashed at the city and went on lashing as the people streamed miserably to work, their legs whipped by the wet hems of their macintoshes and their faces blotching with the cold.

It was a filthy day and everybody said so – even M, who rarely admitted the existence of weather even in its extreme forms. When the old black Silver Wraith Rolls with the nondescript number-plate stopped outside the tall building in Regent’s Park and he climbed stiffly out on to the pavement, hail hit him in the face like a whiff of small-shot. Instead of hurrying inside the building, he walked deliberately round the car to the window beside the chauffeur.

‘Won’t be needing the car again today, Smith. Take it away and go home. I’ll use the tube this evening. No weather for driving a car. Worse than one of those PQ convoys.’

Ex-Leading Stoker Smith grinned gratefully. ‘Aye-aye, sir. And thanks.’ He watched the elderly erect figure walk round the bonnet of the Rolls and across the pavement and into the building. Just like the old boy. He’d always see the men right first. Smith clicked the gear lever into first and moved off, peering forward through the streaming windscreen. They didn’t come like that any more.

M went up in the lift to the eighth floor and along the thick-carpeted corridor to his office. He shut the door behind him, took off his overcoat and scarf and hung them behind the door. He took out a large blue silk bandanna handkerchief and brusquely wiped it over his face. It was odd, but he wouldn’t have done this in front of the porters or the liftman. He went over to his desk and sat down and bent towards the intercom. He pressed a switch. ‘I’m in, Miss Moneypenny. The signals, please, and anything else you’ve got. Then get me Sir James Molony. He’ll be doing his rounds at St Mary’s about now. Tell the Chief of Staff I’ll see 007 in half an hour. And let me have the Strangways file.’ M waited for the metallic ‘Yes, sir’ and released the switch.

He sat back and reached for his pipe and began filling it thoughtfully. He didn’t look up when his secretary came in with the stack of papers and he even ignored the half-dozen pink Most Immediates on top of the signal file. If they had been vital he would have been called during the night.

A yellow light winked on the intercom. M picked up the black telephone from the row of four. ‘That you, Sir James? Have you got five minutes?’

‘Six, for you.’ At the other end of the line the famous neurologist chuckled. ‘Want me to certify one of Her Majesty’s Ministers?’

‘Not today.’ M frowned irritably. The old Navy had respected governments. ‘It’s about that man of mine you’ve been handling. We won’t bother about the name. This is an open line. I gather you let him out yesterday. Is he fit for duty?’

There was a pause on the other end. Now the voice was professional, judicious. ‘Physically he’s as fit as a fiddle. Leg’s healed up. Shouldn’t be any after-effects. Yes, he’s all right.’ There was another pause. ‘Just one thing, M. There’s a lot of tension there, you know. You work these men of yours pretty hard. Can you give him something easy to start with? From what you’ve told me he’s been having a tough time for some years now.’

M said gruffly, ‘That’s what he’s paid for. It’ll soon show if he’s not up to the work. Won’t be the first one that’s cracked. From what you say, he sounds in perfectly good shape. It isn’t as if he’d really been damaged like some of the patients I’ve sent you – men who’ve been properly put through the mangle.’

‘Of course, if you put it like that. But pain’s an odd thing. We know very little about it. You can’t measure it – the difference in suffering between a woman having a baby and a man having a renal colic. And, thank God, the body seems to forget fairly quickly. But this man of yours has been in real pain, M. Don’t think that just because nothing’s been broken . . .’

‘Quite, quite.’ Bond had made a mistake and he had suffered for it. In any case M didn’t like being lectured, even by one of the most famous doctors in the world, on how he should handle his agents. There had been a note of criticism in Sir James Molony’s voice. M said abruptly, ‘Ever hear of a man called Steincrohn – Dr Peter Steincrohn?’

‘No, who’s he?’

‘American doctor. Written a book my Washington people sent over for our library. This man talks about how much punishment the human body can put up with. Gives a list of the bits of the body an average man can do without. Matter of fact, I copied it out for future reference. Care to hear the list?’ M dug into his coat pocket and put some letters and scraps of paper on the desk in front of him. With his left hand he selected a piece of paper and unfolded it. He wasn’t put out by the silence on the other end of the line. ‘Hullo, Sir James! Well, here they are: “Gall bladder, spleen, tonsils, appendix, one of his two kidneys, one of his two lungs, two of his four or five quarts of blood, two-fifths of his liver, most of his stomach, four of his twenty-three feet of intestines and half of his brain.” ’ M paused. When the silence continued at the other end, he said, ‘Any comments, Sir James?’

There was a reluctant grunt at the other end of the telephone. ‘I wonder he didn’t add an arm and a leg, or all of them. I don’t see quite what you’re trying to prove.’

M gave a curt laugh. ‘I’m not trying to prove anything, Sir James. It just struck me as an interesting list. All I’m trying to say is that my man seems to have got off pretty lightly compared with that sort of punishment. But,’ M relented, ‘don’t let’s argue about it.’ He said in a milder voice, ‘As a matter of fact I did have it in mind to let him have a bit of a breather. Something’s come up in Jamaica.’ M glanced at the streaming windows. ‘It’ll be more of a rest cure than anything. Two of my people, a man and a girl, have gone off together. Or that’s what it looks like. Our friend can have a spell at being an inquiry agent – in the sunshine too. How’s that?’

‘Just the ticket. I wouldn’t mind the job myself on a day like this.’ But Sir James Molony was determined to get his message through. He persisted mildly. ‘Don’t think I wanted to interfere, M, but there are limits to a man’s courage. I know you have to treat these men as if they were expendable, but presumably you don’t want them to crack at the wrong moment. This one I’ve had here is tough. I’d say you’ll get plenty more work out of him. But you know what Moran has to say about courage in that book of his.’

‘Don’t recall.’

‘He says that courage is a capital sum reduced by expenditure. I agree with him. All I’m trying to say is that this particular man seems to have been spending pretty hard since before the war. I wouldn’t say he’s overdrawn – not yet, but there are limits.’

‘Just so.’ M decided that was quite enough of that. Nowadays, softness was everywhere. ‘That’s why I’m sending him abroad. Holiday in Jamaica. Don’t worry, Sir James. I’ll take care of him. By the way, did you ever discover what the stuff was that Russian woman put into him?’

‘Got the answer yesterday.’ Sir James Molony also was glad the subject had been changed. The old man was as raw as the weather. Was there any chance that he had got his message across into what he described to himself as M’s thick skull? ‘Taken us three months. It was a bright chap at the School of Tropical Medicine who came up with it. The drug was fugu poison. The Japanese use it for committing suicide. It comes from the sex organs of the Japanese globe-fish. Trust the Russians to use something no one’s ever heard of. They might just as well have used curare. It has much the same effect – paralysis of the central nervous system. Fugu’s scientific name is Tetrodotoxin. It’s terrible stuff and very quick. One shot of it like your man got and in a matter of seconds the motor and respiratory muscles are paralysed. At first the chap sees double and then he can’t keep his eyes open. Next he can’t swallow. His head falls and he can’t raise it. Dies of respiratory paralysis.’

‘Lucky he got away with it.’

‘Miracle. Thanks entirely to that Frenchman who was with him. Got your man on the floor and gave him artificial respiration as if he was drowning. Somehow kept his lungs going until the doctor came. Luckily the doctor had worked in South America. Diagnosed curare and treated him accordingly. But it was a chance in a million. By the same token, what happened to the Russian woman?’

M said shortly, ‘Oh, she died. Well, many thanks, Sir James. And don’t worry about your patient. I’ll see he has an easy time of it. Goodbye.’

M hung up. His face was cold and blank. He pulled over the signal file and went quickly through it. On some of the signals he scribbled a comment. Occasionally he made a brief telephone call to one of the Sections. When he had finished he tossed the pile into his Out basket and reached for his pipe and the tobacco jar made out of the base of a fourteen-pounder shell. Nothing remained in front of him except a buff folder marked with the Top Secret red star. Across the centre of the folder was written in block capitals: CARIBBEAN STATION, and underneath, in italics, Strangways and Trueblood.

A light winked on the intercom. M pressed down the switch. ‘Yes?’

‘007’s here, sir.’

‘Send him in. And tell the Armourer to come up in five minutes.’

M sat back. He put his pipe in his mouth and set a match to it. Through the smoke he watched the door to his secretary’s office. His eyes were very bright and watchful.

James Bond came through the door and shut it behind him. He walked over to the chair across the desk from M and sat down.

‘Morning, 007.’

‘Good morning, sir.’

There was silence in the room except for the rasping of M’s pipe. It seemed to be taking a lot of matches to get it going. In the background the fingernails of the sleet slashed against the two broad windows.

It was all just as Bond had remembered it through the months of being shunted from hospital to hospital, the weeks of dreary convalescence, the hard work of getting his body back into shape. To him this represented stepping back into life. Sitting here in this room opposite M was the symbol of normality he had longed for. He looked across through the smoke clouds into the shrewd grey eyes. They were watching him. What was coming? A post-mortem on the shambles which had been his last case? A curt relegation to one of the home sections for a spell of desk work? Or some splendid new assignment M had been keeping on ice while waiting for Bond to get back to duty?

M threw the box of matches down on the red leather desk. He leant back and clasped his hands behind his head.

‘How do you feel? Glad to be back?’

‘Very glad, sir. And I feel fine.’

‘Any final thoughts about your last case? Haven’t bothered you with it till you got well. You heard I ordered an inquiry. I believe the Chief of Staff took some evidence from you. Anything to add?’

M’s voice was businesslike, cold. Bond didn’t like it. Something unpleasant was coming. He said, ‘No, sir. It was a mess. I blame myself for letting that woman get me. Shouldn’t have happened.’

M took his hands from behind his neck and slowly leant forward and placed them flat on the desk in front of him. His eyes were hard. ‘Just so.’ The voice was velvet, dangerous. ‘Your gun got stuck, if I recall. This Beretta of yours with the silencer. Something wrong there, 007. Can’t afford that sort of mistake if you’re to carry an 00 number. Would you prefer to drop it and go back to normal duties?’

Bond stiffened. His eyes looked resentfully into M’s. The licence to kill for the Secret Service, the Double 0 prefix, was a great honour. It had been earned hardly. It brought Bond the only assignments he enjoyed, the dangerous ones. ‘No, I wouldn’t, sir.’

‘Then we’ll have to change your equipment. That was one of the findings of the Court of Inquiry. I agree with it. D’you understand?’

Bond said obstinately, ‘I’m used to that gun, sir. I like working with it. What happened could have happened to anyone. With any kind of gun.’

‘I don’t agree. Nor did the Court of Inquiry. So that’s final. The only question is what you’re to use instead.’ M bent forward to the intercom. ‘Is the Armourer there? Send him in.’

M sat back. ‘You may not know it, 007, but Major Boothroyd’s the greatest small-arms expert in the world. He wouldn’t be here if he wasn’t. We’ll hear what he has to say.’

The door opened. A short slim man with sandy hair came in and walked over to the desk and stood beside Bond’s chair. Bond looked up into his face. He hadn’t often seen the man before, but he remembered the very wide-apart clear grey eyes that never seemed to flicker. With a non-committal glance down at Bond, the man stood relaxed, looking across at M. He said ‘Good morning, sir,’ in a flat, unemotional voice.

‘Morning, Armourer. Now I want to ask you some questions.’ M’s voice was casual. ‘First of all, what do you think of the Beretta, the .25?’

‘Ladies’ gun, sir.’

M raised ironic eyebrows at Bond. Bond smiled thinly.

‘Really! And why do you say that?’

‘No stopping power, sir. But it’s easy to operate. A bit fancy-looking too, if you know what I mean, sir. Appeals to the ladies.’

‘How would it be with a silencer?’

‘Still less stopping power, sir. And I don’t like silencers. They’re heavy and get stuck in your clothing when you’re in a hurry. I wouldn’t recommend anyone to try a combination like that, sir. Not if they were meaning business.’

M said pleasantly to Bond, ‘Any comment, 007?’

Bond shrugged his shoulders. ‘I don’t agree. I’ve used the .25 Beretta for fifteen years. Never had a stoppage and I haven’t missed with it yet. Not a bad record for a gun. It just happens that I’m used to it and I can point it straight. I’ve used bigger guns when I’ve had to – the .45 Colt with the long barrel, for instance. But for close-up work and concealment I like the Beretta.’ Bond paused. He felt he should give way somewhere. ‘I’d agree about the silencer, sir. They’re a nuisance. But sometimes you have to use them.’

‘We’ve seen what happens when you do,’ said M dryly. ‘And as for changing your gun, it’s only a question of practice. You’ll soon get the feel of a new one.’ M allowed a trace of sympathy to enter his voice. ‘Sorry, 007. But I’ve decided. Just stand up a moment. I want the Armourer to get a look at your build.’

Bond stood up and faced the other man. There was no warmth in the two pairs of eyes. Bond’s showed irritation. Major Boothroyd’s were indifferent, clinical. He walked round Bond. He said ‘Excuse me’ and felt Bond’s biceps and forearms. He came back in front of him and said, ‘Might I see your gun?’

Bond’s hand went slowly into his coat. He handed over the taped Beretta with the sawn barrel. Boothroyd examined the gun and weighed it in his hand. He put it down on the desk. ‘And your holster?’

Bond took off his coat and slipped off the chamois leather holster and harness. He put his coat on again.

With a glance at the lips of the holster, perhaps to see if they showed traces of snagging, Boothroyd tossed the holster down beside the gun with a motion that sneered. He looked across at M. ‘I think we can do better than this, sir.’ It was the sort of voice Bond’s first expensive tailor had used.

Bond sat down. He just stopped himself gazing rudely at the ceiling. Instead he looked impassively across at M.

‘Well, Armourer, what do you recommend?’

Major Boothroyd put on the expert’s voice. ‘As a matter of fact, sir,’ he said modestly, ‘I’ve just been testing most of the small automatics. Five thousand rounds each at twenty-five yards. Of all of them, I’d choose the Walther PPK 7.65 mm. It only came fourth after the Japanese M-14, the Russian Tokarev and the Sauer M-38. But I like its light trigger pull and the extension spur of the magazine gives a grip that should suit 007. It’s a real stopping gun. Of course it’s about a .32 calibre as compared with the Beretta’s .25, but I wouldn’t recommend anything lighter. And you can get ammunition for the Walther anywhere in the world. That gives it an edge on the Japanese and the Russian guns.’

M turned to Bond. ‘Any comments?’

‘It’s a good gun, sir,’ Bond admitted. ‘Bit more bulky than the Beretta. How does the Armourer suggest I carry it?’

‘Berns Martin Triple-draw holster,’ said Major Boothroyd succinctly. ‘Best worn inside the trouser band to the left. But it’s all right below the shoulder. Stiff saddle leather. Holds the gun in with a spring. Should make for a quicker draw than that,’ he gestured towards the desk. ‘Three-fifths of a second to hit a man at twenty feet would be about right.’

‘That’s settled then.’ M’s voice was final. ‘And what about something bigger?’

‘There’s only one gun for that, sir,’ said Major Boothroyd stolidly. ‘Smith & Wesson Centennial Airweight. Revolver. .38 calibre. Hammerless, so it won’t catch in clothing. Overall length of six and a half inches and it only weighs thirteen ounces. To keep down the weight, the cylinder holds only five cartridges. But by the time they’re gone,’ Major Boothroyd allowed himself a wintry smile, ‘somebody’s been killed. Fires the .38 S & W Special. Very accurate cartridge indeed. With standard loading it has a muzzle velocity of eight hundred and sixty feet per second and muzzle energy of two hundred and sixty foot-pounds. There are various barrel lengths, three and a half inch, five inch . . .’

‘All right, all right.’ M’s voice was testy. ‘Take it as read. If you say it’s the best, I’ll believe you. So it’s the Walther and the Smith & Wesson. Send up one of each to 007. With the harness. And arrange for him to fire them in. Starting today. He’s got to be expert in a week. All right? Then thank you very much, Armourer. I won’t detain you.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Major Boothroyd. He turned and marched stiffly out of the room.

There was a moment’s silence. The sleet tore at the windows. M swivelled his chair and watched the streaming panes. Bond took the opportunity to glance at his watch. Ten o’clock. His eyes slid to the gun and holster on the desk. He thought of his fifteen years’ marriage to the ugly bit of metal. He remembered the times its single word had saved his life – and the times when its threat alone had been enough. He thought of the days when he had literally dressed to kill – when he had dismantled the gun and oiled it and packed the bullets carefully into the spring-loaded magazine and tried the action once or twice, pumping the cartridges out on to the bedspread in some hotel bedroom somewhere round the world. Then the last wipe of a dry rag and the gun into the little holster and a pause in front of the mirror to see that nothing showed. And then out of the door and on his way to the rendezvous that was to end with either darkness or light. How many times had it saved his life? How many death sentences had it signed? Bond felt unreasonably sad. How could one have such ties with an inanimate object, an ugly one at that, and, he had to admit it, with a weapon that was not in the same class as the ones chosen by the Armourer? But he had the ties and M was going to cut them.

M swivelled back to face him. ‘Sorry, James,’ he said, and there was no sympathy in his voice. ‘I know how you like that bit of iron. But I’m afraid it’s got to go. Never give a weapon a second chance – any more than a man. I can’t afford to gamble with the Double 0 Section. They’ve got to be properly equipped. You understand that? A gun’s more important than a hand or a foot in your job.’

Bond smiled thinly. ‘I know, sir. I shan’t argue. I’m just sorry to see it go.’

‘All right then. We’ll say no more about it. Now I’ve got some more news for you. There’s a job come up. In Jamaica. Personnel problem. Or that’s what it looks like. Routine investigation and report. The sunshine’ll do you good and you can practise your new guns on the turtles or whatever they have down there. You can do with a bit of holiday. Like to take it on?’

Bond thought: He’s got it in for me over the last job. Feels I let him down. Won’t trust me with anything tough. Wants to see. Oh well! He said: ‘Sounds rather like the soft life, sir. I’ve had almost too much of that lately. But if it’s got to be done . . . If you say so, sir . . .’

‘Yes,’ said M. ‘I say so.’

03

Holiday Task

It was getting dark. Outside the weather was thickening. M reached over and switched on the green-shaded desk-light. The centre of the room became a warm yellow pool in which the leather top of the desk glowed blood-red.

M pulled the thick file towards him. Bond noticed it for the first time. He read the reversed lettering without difficulty. What had Strangways been up to? Who was Trueblood?

M pressed a button on his desk. ‘I’ll get the Chief of Staff in on this,’ he said. ‘I know the bones of the case, but he can fill in the flesh. It’s a drab little story, I’m afraid.’

The Chief of Staff came in. He was a colonel in the Sappers, a man of about Bond’s age, but his hair was prematurely grey at the temples from the endless grind of work and responsibility. He was saved from a nervous breakdown by physical toughness and a sense of humour. He was Bond’s best friend at headquarters. They smiled at each other.

‘Bring up a chair, Chief of Staff. I’ve given 007 the Strangways case. Got to get the mess cleared up before we make a new appointment there. 007 can be Acting Head of Station in the meantime. I want him to leave in a week. Would you fix that with the Colonial Office and the Governor? And now let’s go over the case.’ He turned to Bond. ‘I think you knew Strangways, 007. See you worked with him on that treasure business about five years ago. What did you think of him?’

‘Good man, sir. Bit highly strung. I’d have thought he’d have been relieved by now. Five years is a long time in the tropics.’

M ignored the comment. ‘And his number two, this girl Trueblood, Mary Trueblood. Ever come across her?’

‘No, sir.’

‘I see she’s got a good record. Chief Officer WRNS and then came to us. Nothing against her on her Confidential Record. Good-looker to judge from her photographs. That probably explains it. Would you say Strangways was a bit of a womaniser?’

‘Could have been,’ said Bond carefully, not wanting to say anything against Strangways, but remembering the dashing good looks. ‘But what’s happened to them, sir?’

‘That’s what we want to find out,’ said M. ‘They’ve gone, vanished into thin air. Both went on the same evening about three weeks ago. Left Strangways’s bungalow burnt to the ground – radio, code-books, files. Nothing left but a few charred scraps. The girl left all her things intact. Must have taken only what she stood up in. Even her passport was in her room. But it would have been easy for Strangways to cook up two passports. He had plenty of blanks. He was Passport Control Officer for the island. Any number of planes they could have taken – to Florida or South America or one of the other islands in his area. Police are still checking the passenger lists. Nothing’s come up yet, but they could always have gone to ground for a day or two and then done a bunk. Dyed the girl’s hair and so forth. Airport security doesn’t amount to much in that part of the world. Isn’t that so, Chief of Staff?’