8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

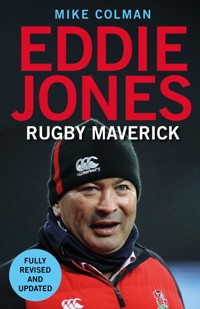

The first biography of the enigmatic coach who has completely transformed the England rugby team. After Eddie Jones began coaching England's rugby team, they won 22 of their next 23 matches. The side that limped out of the 2015 World Cup was thoroughly revitalised. But who was the unconventional figure responsible for this change of fortune? And, given recent setbacks, will Eddie be able to inspire England to bring their best to the 2019 World Cup? From his school days playing alongside the legendary Ella brothers to his masterminding of Japan's jaw-dropping World Cup victory over South Africa, Eddie Jones has always been a polarising figure, known for his punishing work ethic. Constantly controversial, never complacent, Jones has truly shaken up English rugby. Drawing on over a hundred interviews with former teammates, players, administrators, coaching colleagues and Jones himself, veteran rugby writer Mike Colman brings a rare level of insight to his biography of this singular man.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE:THE EX-SON-IN-LAW

1LARPA BOYS

2LITTLE GREEN MAN

3SCHOOL OF HARD KNOCKS

4CLASS ACT

5FIGHTING HARADA

6BOSS WALLABY

7THE CLIVE AND EDDIE SHOW

8ALL OR NOTHING

9DOWN AND OUT

10THE HELP

11RED FACES

12INSIDE THE BOKS

13RUGBY SAMURAI

14EDDIE-SAN

15THE BLOSSOM AND THE ROSE

16NO DAME EDNA

17THE EDDIE EFFECT

18UNSTEADY EDDIE

19THE HOME STRETCH

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PICTURE SECTION

List of Illustrations

Matraville’s 1977 first XV, featuring Eddie (circled in second row), Glen Ella (circled in front row) and Mark Ella, third from the left in the front row. The team captain holding the ball is future Wallaby Lloyd Walker.

Eddie, far left, with his team mates at Randwick including Mark Ella (fourth from left) and Lloyd Walker (far right).

Eddie with future Wallabies coach Ewen McKenzie following a Randwick win.

Playing for NSW (#2) on the 1989 Lions tour of Australia.

Eddie with International Grammar School colleagues Rita Fin and Peter Balding, on a mufti day in December 1987 when the staff came dressed as the students.

Eddie (wearing red jumper), sitting between Rita Fin and Reg St Leon in the International Grammar School staff photo, 1987.

ACT Brumbies captain and halfback George Gregan and coach Eddie field questions at a press conference in May 2000.

Eddie and John Eales in the Wallabies’ dressing room following victory in the Bledisloe Cup, 2001.

Training drills for the Wallabies, August 2004.

A tense Eddie, coaching the Reds, looks on as his team loses to Western Force 38-3 in the Super 14 competition, March 2007.

Jake White, Eddie and Allister Coetzee celebrating South Africa’s victory over England in the final of the IRB 2007 Rugby World Cup.

A Japanese fan shows his support for Eddie during the 2015 World Cup match between USA and Japan.

Early in his England tenure, Eddie leads his squad in a training session at Pennyhill Park.

Eddie celebrates with Danny Care following England’s victory over the Wallabies in Melbourne, June 2016.

Eddie and his schoolfriend (then England skills coach) Glen Ella at Sydney’s Coogee Beach during the England tour of Australia, 2016.

Eddie accepts the World Rugby Coach of the Year Award from Sir Clive Woodward in Monaco, November 2017.

Eddie with wife Hiroko chatting to fellow Australian, sporting legend Rod Laver and Andrea Eliscu in the royal box during Wimbledon 2017.

Irish fans send a message to Eddie following the Six Nations clash between England and Ireland at Twickenham on St Patrick’s Day, 2018.

Maverick: A person who thinks and acts in an independent way, often behaving differently from the expected or usual way.

(Cambridge English Dictionary)

Prologue

THE EX-SON-IN-LAW

Eddie Jones is the ex-son-in-law who has gone away and made good. Now he’s back and wants to buy the big house across the road. Every time you open the front curtains he wants you to see him driving in and out in his Rolls Royce, and he wants you to think, ‘We never should have let him go.’

Courier-Mail, 10 June 2016

When Eddie Jones brought his team to Australia six months after being appointed England coach he scoffed at suggestions he was seeking revenge over the country that had cast him aside. Not too many believed him. As one columnist noted: ‘Eddie Jones has a long memory.’

Sacked as Wallaby coach in 2005, Eddie had endured an at-times torturous climb back to the top of world rugby over the following decade. Humiliated during an abortive one-season stint at the Queensland Reds, he was then roundly criticized in Australia for assisting South Africa in its successful 2007 Rugby World Cup campaign. Another disheartening term cut short with English club Saracens saw him coaching corporate rugby in Japan, a far cry from the glory days of leading Australia to the final of the 2003 World Cup. It was only the stunning upset win by his Japanese ‘Brave Blossoms’ over the Springboks at the 2015 World Cup that saw him back in the frame and appointed to coach England, the best-resourced team in world rugby.

With the English scheduled to embark on a three-Test tour of Australia in June 2016, well before his appointment, the series against the World Cup finalists could not have provided a better opportunity for Eddie to prove a point to his many detractors down under.

Rarely has there been a character in Australian sport who has polarized opinion to the degree of Eddie Jones. His most favoured ex-players and staff members avow that while a perfectionist workaholic and hard task-master, he can be warm, funny and loyal. Those in the opposing camp are just as vehement that he is despotic, cruel and unreasonable. Former Wallabies such as Elton Flatley and Wendell Sailor describe him as the best coach they ever had. Others, including former Australian Rugby Union boss John O’Neill, are quick to label him almost impossible to work with.

None of this is a secret to Eddie, who knows that there were many, past and present, in the corridors of power at ARU headquarters who all but rejoiced in his very public fall from grace following the 2003 RWC final.

All of this combined to make the 2016 mid-year series the most eagerly anticipated for years. Since the heady days of the 2003 World Cup, which netted hosts Australia an unprecedented $43 million windfall, the stock of the Wallabies had fallen alarmingly. With Eddie sacked after eight losses from nine Tests, former Queensland coach John Connolly was given the task of mounting Australia’s campaign at the 2007 World Cup. It ended in the quarter-finals, with the Wallabies’ nemesis Jonny Wilkinson kicking four penalty goals in England’s 12-10 win. Eight months later, John O’Neill took the unprecedented step of hiring Australia’s first-ever foreign-born head coach in former All Blacks assistant Robbie Deans.

Deans, who had enjoyed great success as coach of the Canterbury Crusaders, taking them to five Super Rugby titles, was seen as the man to halt the disturbing slide in rugby’s popularity in Australia. Just prior to Deans’ appointment, O’Neill had commissioned a report on the game’s health. In summary it read: cash down, crowds down, TV ratings down and participation rates down 1.8 per cent – the first drop in ten years.

The hoped-for Deans-led revival never came. Live TV coverage on Channel 7 of his first Test in charge, an 18-12 win over Ireland in Melbourne, was out-rated by a rerun of the movie Richie Rich on rival network Channel 9. In the lead-up to the Wallabies’ next match, against France at Sydney’s 80,000-seat ANZ Stadium a fortnight later, ticket sales were so slow that stadium management offered them free to anyone who spent more than $80 at a local shopping centre. An ambitious national second-tier competition proved little more than a money pit, draining the ARU ‘war-chest’ down to just $8 million.

High hopes had been held for the 2011 Rugby World Cup in New Zealand, but it too was a disappointment. Deans placed enormous faith in his precocious backline stars James O’Connor, Kurtley Beale and Quade Cooper – dubbed ‘The Three Amigos’ by the Australian press corps – but they failed to live up to his expectations. Mercurial fly-half Cooper was hounded from one end of New Zealand to the other by crowds and local media, who labelled him ‘Public Enemy Number One’. His confidence shot, he fell apart, and the team’s attack imploded with him. The Wallabies lost their pool match against Ireland and were shown the exit door 20-6 in the semi-final by eventual Cup winners the All Blacks. Deans followed eighteen months later after a series loss to the British and Irish Lions.

If things were bad they were going to get worse. Replacing Deans was former Wallaby front-rower Ewen ‘Link’ McKenzie whose tenure ended controversially three years later following a much-publicized clash between Beale and a team manager.

With the public image of Australian rugby at its lowest ebb, the dubious honour of coaching the Wallabies was handed to Eddie’s former Randwick team-mate Michael Cheika.

The playing styles of Eddie and Cheika could not have been more different: Eddie a diminutive hooker as renowned for his ceaseless chatter as high work-rate, Cheika a hard-boiled back-rower who preferred to let his take-no-prisoners physicality do his talking for him.

It is the same with their coaching styles. Eddie has a reputation for ripping into his players and coaching assistants with his razor-sharp tongue, his sarcasm and straight-out abuse known to reduce even hardened Test forwards to tears. Cheika is more likely to use his powerful body language to get the message across, as Eddie noted: ‘We played four or five years together. He was pretty rough and tough. He was always smart, always a thinker, but he definitely had a temper. I think maybe he’s got control of that now that he’s got older, but he still has that aura that allows him to impose his personality on his players.’

As Wallaby scrum-half Nick Phipps put it, ‘Sometimes if someone makes a mistake Cheik will rub it in with a bit of a laugh. Other times . . . well, there’s no laughing.’

Stories of Cheika’s toughness during his playing days are legendary. Long-time Randwick player and coach Jeff Sayle tells the story of Cheika copping a boot to the head that required thirty-eight stitches and showing up at training four days later determined to play the following weekend. Sayle took one look at the festering wound and told him to get to a doctor.

‘If the doctor says you can play, you can play,’ Sayle said, knowing the chances of that were nil. The doctor did a quick examination and booked him into hospital for immediate treatment. The scar is still evident, although not as prominent as the cauliflower ears Cheika earned in over three hundred club games.

But while on-field they might have been poles apart, off-field Eddie and Cheika had followed a similar road to get to the top of international coaching. When Eddie, the son of an Australian father and Japanese mother, described Cheika to a reporter during the 2015 Rugby World Cup, he could have been talking about himself.

‘I think he was always a bit of an outsider, a Lebanese kid in what was then an upper-class private-school game. I think that’s why he was so determined to make it.’

And make it he did, at just about everything he put his mind to. When his playing career ended in 1999, Cheika moved into coaching at Italian club Padova. In 2001, when his father fell ill, he returned to Australia and coached Randwick, taking them to the Sydney premiership in 2004. The following year he joined Leinster, in 2009 coaching the Irish club to its first-ever European title with a 19-16 Heineken Cup victory over Leicester Tigers at Murrayfield. In 2014 he coached NSW Waratahs to the Super Rugby title, becoming the first coach to win major professional competitions in both northern and southern hemispheres.

At the same time as playing and coaching rugby, Cheika was establishing a highly successful wholesale fashion operation in Australia and Europe. A millionaire many times over and fluent in English, Lebanese, French and Italian, Cheika has a rough exterior that belies a shrewd business mind, as ARU officials found when they faced him over the negotiating table.

Three months after the Waratahs’ historic Super Rugby victory, with the sudden departure of Ewen McKenzie, he was appointed Australian coach. Four days after that, he was introducing himself to Wallaby players at the airport as they headed to England to start their four-Test spring tour. With just one win, over Wales, and losses to Ireland, France and England, the tour was not successful on the scoreboard but in terms of laying the first foundation stones for Australia’s 2015 Rugby World Cup campaign it was invaluable.

A year after being handed control of a team in turmoil, Cheika took the Wallabies all the way to the World Cup final, in the process dealing a killer blow to Stuart Lancaster’s England side and opening the door to the biggest career opportunity of Eddie Jones’ life.

Upset by Wales in their second pool match, England had to beat Australia at Twickenham in their next game in order to make it through to the quarter-finals. Instead, the Wallabies produced their best World Cup performance since Eddie’s side had beaten New Zealand in the semi-final of the 2003 tournament, belting England 33-13 and handing them the unwanted title of first World Cup hosts to be eliminated in the pool stage. The loss rendered England’s next game against Uruguay meaningless and ended Lancaster’s tenure in failure. With Eddie given the job, and handed a blank cheque by England’s Rugby Football Union to turn things around, the stage was set for a series to remember in Australia.

Rarely do the stars align as they did when Eddie and his men arrived at Brisbane airport on Thursday, 2 June 2016. The machinations behind the scenes couldn’t have been more perfect if they had been scripted by Rugby Australia’s marketing department. There was Eddie, the disgruntled former coach, riding into town at the head of the white-shirted Poms, who had snatched the World Cup from Australia’s grasp back in 2003; the confident Wallabies, who had brushed England aside on their way to the RWC final just eight months earlier; an England side still smarting from the embarrassment dealt to them by Australia on their own ground; and two fiercely competitive ex-teammates, outwardly friendly, but desperately keen to finish the series with bragging rights. To add even more spice to the mix, if England won they would leap-frog Australia to the number two world ranking behind New Zealand. There was also the matter of the World Rugby Coach of the Year award bestowed on Cheika after the World Cup. Many believed it should have gone to the All Blacks’ Steve Hanson or even, after the heroics of the Brave Blossoms, Eddie. Given how many times he alluded to it throughout the tour, it would appear that Eddie fell into the latter group.

A lot had changed in Australian rugby since Eddie had left under a cloud over ten years earlier, but there was still one direct link to his time as national coach. Captaining the Wallabies was hooker Stephen Moore, the last remaining player from Eddie’s time in charge of the team. Moore, who had made his Test debut in 2005, could well have ended up playing for Ireland if not for Eddie’s intervention.

‘It was in 2003 just after the World Cup. I was nineteen at the time, studying at Queensland University and playing for the university club. I was in the Australian Under-21 squad but I hadn’t played any senior representative football at that stage. My parents are both Irish, and there was a bit of interest from the Irish Rugby Union asking if I’d be interested in going over and playing for one of the provinces and maybe playing for Ireland. I remember I was at uni waiting to go into a lecture one day and my phone rang, and it was Eddie. It was, how can I put this . . . an animated conversation. He was like, “Mate, we want you to sign with the ARU. You need to sign straight away.” It was my first interaction with him, but I remember at Under-21 camps I’d see Wallabies standing around sweating bullets waiting to go in for meetings with Eddie and they’d come out soaked in sweat, so he was a pretty daunting character. It was pretty intimidating. I was scared to be honest. I got off the phone and rang my mum and dad straight away. I signed the next day, and it was 100 per cent the right thing to do. I’ve never regretted it for a moment. That’s just the way Eddie was, big on detail, very professional. He taught me a lot about trying to be the best in the world at what you do. I knew that playing against a team coached by Eddie would be hard. I was pretty young when I played under Eddie, first at the Wallabies and then the Reds, but I’ve always thought I would have loved to play under him as a senior player. He knows what is important when it comes to winning. He has a good grasp of that; it’s something I’ve always admired about him.’

When Eddie’s flight touched down, the only people happier than ARU officials with their looming financial bonanza were the Australian rugby media. Nobody gave better copy than Eddie, and Cheika was no slouch either, as evidenced by his outburst after the New Zealand Herald printed a caricature of him dressed as a clown ahead of an All Black Test. Even so, Cheika refused to be drawn into a war of words with Eddie throughout the series. Not that it mattered. Eddie did enough stirring for both of them. Even before he’d left the airport to head to the team hotel he made his theme for the tour clear: he would be playing the role of the victim.

‘I just went through immigration and I got shunted through the area where everything got checked. That’s what I’m expecting, mate. Everything that’s done around the game is going to be coordinated. All coordinated to help Australia win. We’ve got to be good enough to control what we can control. Australia are second in the world. They’ve got the best coach in the world. They’re playing in their own backyard; they’re going to be strong favourites for the tour. Our record in Australia is three Tests since Captain Cook arrived, so it’s not a great record, is it?’

Perhaps not, but the England side Eddie had shaped since taking on the job was very different from the one that the Wallabies had destroyed at Twickenham in their previous meeting. Different, in fact, from any England side that had ever toured Australia. Recently crowned champions of Europe following their Grand Slam win in the Six Nations, they were fit, strong, fiercely combative and, just like their coach, had plenty to prove against the Wallabies.

Before announcing his touring squad, Eddie made a statement that he, more than anyone, knew would incite Australians. A great lover of cricket and well versed in the game’s history, he invoked memories of the infamous 1932–33 Ashes series, during which the England leg-side tactics sparked a diplomatic crisis between the two countries.

‘We’ve got to take a side down there to play Bodyline. If we’re going to beat Australia in Australia, we’ve got to have a completely physical, aggressive team.’

Eddie later claimed that by ‘Bodyline rugby’ he meant England would have to be inventive, rather than violent, if they were to upset the Wallabies.

‘It’s a figure of speech. The whole thing is, we’ve got to do something different here. We can’t do what’s been done by previous English teams. We’ve got to have a different mindset, a different way of how we play the game against Australia to change history.’

Regardless of the semantics, the result was the same. England ran out for the first Test determined to overpower the Wallabies in the forwards, and that is exactly what they did. After Australia had shot out to a two-try 10-0 lead after fifteen minutes, it looked like England’s six-Test unbeaten run under Eddie was about to come to an inglorious end. Instead, the boot of Owen Farrell drew them within a point, 9-10, before the English forwards, led by flankers James Haskell and Chris Robshaw, the Vunipola brothers, front-rower Mako and number eight Billy, and exciting lock Maro Itoje, took control. The scoresheet showed that Australia scored four tries to three and had another disallowed in going down 28-39, but no one who saw the game was in any doubt: this was a win to England every bit as comprehensive as the loss they had suffered at the hands of the Wallabies eight months earlier.

It was England’s first-ever win in Brisbane and the most points they had ever scored against Australia. It also gave Eddie a perfect six-from-six Test record at Suncorp Stadium after five wins with the Wallabies. The joy it gave him was evident from the way he jumped to his feet, arms raised above his head, before ‘high-fiving’ his friend and assistant coach Glen Ella as wing replacement Jack Nowell ran onto a perfectly weighted George Ford kick to score the win-clinching try.

So happy was Eddie, in fact, that even he might have struggled to find a reason to continue his victim routine if not for the untimely intrusion at the post-match media conference of a camera crew led by former Wallaby back-rower Stephen Hoiles.

Hoiles, who had been handed his first Test jersey by Eddie in 2004, was working for The Other Rugby Show, a new ‘alternative’ cable TV programme on the Fox Sports network, official broadcasters of the Test series. With its premiere episode airing the following week, the producers had concocted a supposedly humorous segment in which Hoiles would be given a list of unrelated words and have to include them in a question to Eddie. It backfired horribly. Not only were legitimate journalists appalled and angry at having their workplace invaded by a second-rate comedy act, it gave Eddie ammunition to use as motivation for his team in the lead-up to the second Test.

Hoiles’ question was: ‘You seem to be in the press a bit more than Donald Trump this week, and the lads were pumped up. There was a bit of moisture out there, and I think you and Glen had a good moment, looked lubed-up and a fair bit of shrinkage. How did you enjoy that moment with your old mate Glen up in the box?’

Caught off guard, Eddie answered: ‘Sorry? Repeat the question, mate. I don’t like the tone of the question, mate . . . Are we not allowed to enjoy a win, mate?’

There was an awkward silence before a serious question was asked by a member of the working press, but after the media conference had broken up and he had regained his composure, Eddie was quick to get stuck into Hoiles and also the Fox Sports promotional campaign that featured former Wallabies turned Fox commentators Tim Horan, Phil Kearns, Greg Martin and Rod Kafer making fun of English rugby failures. Asked if Holies had disrespected him, he replied: ‘Without a doubt. You get that sort of ridiculous question from Hoiles. You’ve seen the Fox promos, they are disgusting. All I am saying is there’s been quite a disrespectful way in which the team has been treated in the media here. It is quite demeaning, disrespectful to the team, so we’re not going to let this opportunity pass.’

The segment never aired, with host Sean Maloney instead offering an apology to Eddie, the England team and the working media for any offence caused. Hoiles also contacted Eddie personally to apologize. It was an apology that Eddie accepted, but he still milked the situation for all it was worth, before moving on to Melbourne with a parting dig at Cheika.

‘They’ve got the world’s best coach, and the expectation’s high for them. The pressure’s on them next week.’

If Eddie was starting to irritate his old team-mate with continued references to his Coach of the Year award, Cheika wasn’t showing it, telling reporters who asked why he wasn’t returning serve, ‘He hasn’t called me fat or bald or anything.’

Besides, it wasn’t snide comments from Eddie that Cheika was concerned with. It was his team’s inability to beat England.

The second Test was another win to the visitors, this time 27-3, an astonishing result given Australia’s dominance everywhere except the scoreboard. Incredibly, the Wallabies had 70 per cent of possession, ran the ball 172 times to England’s 53, and gained 962 run metres to England’s 282. Most telling of all, England were forced to make 217 tackles against Australia’s 81.

It was a series-clinching win that defied logic, but Eddie gave reporters one of his best lines of the tour, claiming that giving the Wallabies so much ball that they ran out of steam was a move borrowed from Muhammad Ali’s famous tactic against George Foreman in 1974’s ‘Rumble in the Jungle’: ‘We had to play Rope-a-Dope today,’ he said.

Wallaby fly-half Bernard Foley isn’t too sure about the Ali–Foreman analogy, but he does know that England were well prepared that night and followed Eddie’s instructions to a tee.

‘That was very smart the way they changed their game plan from the first Test. That had been our first match since the World Cup, and we expected the momentum to continue, which was poor judgement on our part. We were both different teams to what we had been at Twickenham. We had four players making their debuts on a week’s preparation, and England were a different beast to what they had been. They had a new strategy and they implemented it well. We underestimated what needed to be done. In saying that, we couldn’t have started that first game better. We scored some good tries and then we made an error, and they capitalized. They got on a roll, and we struggled to stop the flow. That changed everything for the next game in Melbourne. The expectation was all on us. We were the ones in a must-win situation to keep the series alive. Eddie knew we would be throwing everything at them and they changed their structure so they were defending more in a line. They kept tackling, we kept chasing the win, and when they got a chance they scored.’

For Eddie it was proof positive that all the hard work he and the team had been doing for the previous six months had paid off. Not only had England beaten their European rivals, they had also been able to adapt to Southern Hemisphere conditions and tactics.

‘We have to be tactically flexible in Test rugby,’ Eddie said. ‘That’s why I’m so pleased. They had all the ball, and then we had the opportunity to score a try and we took it. That’s the sign of a good side.’

A side that, with the series and world number-two ranking safely locked away, now had another goal: a 3-0 whitewash.

‘The boys started talking about it on the field, and we’re committed to doing that. We want to be the best team in the world. If the All Blacks were in this situation now, what would they be thinking? They’d be thinking 3-0. If we want to be the best team in the world, we have to think 3-0.’

And 3-0 it was. The record highest score against Australia of 39 that England had posted in the first Test lasted just two weeks, with Eddie’s men ending their tour with a 44-40 victory. It was the first 3-0 series drubbing the Wallabies had suffered since they went down to the Springboks in 1971. Eddie resisted the opportunity to gloat at the post-match media call, describing the banter throughout the series as ‘all a bit of fun’, and allowed himself only one minor dig at the country of his birth.

‘It’s been great to be in Australia,’ he said. ‘Obviously, being an Australian, I’m always grateful to Australia for what they’ve done for me in rugby . . .’ He then flashed the tiniest of cheeky smiles. ‘. . . but it’s certainly nice beating them 3-0.’

He then twisted the knife ever so slightly, making special mention of the work Australia’s long-time tormentor Jonny Wilkinson had done with the England kickers Owen Farrell and George Ford prior to the tour. Farrell, whose goal-kicking Eddie described as ‘solar-system class’, had been the difference in the third Test, booting a Wilkinson-like twenty-four points.

Australian captain Stephen Moore, who retired in 2017 with 129 caps, believes the Wallabies, playing their first Tests of the season, weren’t in the right mental place to withstand the battle-hardened Englishmen.

‘There’s no doubt we took things for granted after 2015. We thought the spirit and culture that we’d built up through the World Cup would just follow over. On the flip side, England had a lot to prove after being bowled out of their own tournament. It was a hell of a series, though. Both sides played good footy. They were some of the best opposition I ever encountered in my career and they showed what a good team they were over the next couple of seasons. Given the way Eddie left the Wallabies, I’m sure he would have enjoyed it, but Eddie is a proud Australian and he has never shied away from that.’

The question over Eddie’s allegiances has long been a matter of debate. Many believe that a former national coach should not be coaching another country against his old team. Eddie always makes it clear that there is a distinction between one’s country of birth and their country of employment, and whoever pays him will have his loyalty.

At the media conference after the final Test of the series he was asked by an Australian journalist if he believed the success of England’s defence against Australia’s policy of all-out attack had proved the Wallabies needed to be more flexible.

‘They’re well coached,’ he answered. ‘They’ll work it out for themselves. I’m not coaching Australia. I’m coaching England, and it’s an honour for me to coach England. If I was coaching Australia, I’d tell you.’

A year later he gave a more telling insight into his feelings at the time when recounting an experience he had had at the start of the first Test in Brisbane.

‘I’m Australian and I love Australia, but any semblance of a conflict was destroyed when I walked up the grandstand and sat in the box, and there was this woman sitting outside. She was immaculately dressed. She had the Yves Saint Laurent shoes on, the nice scarf, everything. And she turns after the national anthems and starts giving me the finger and an assortment of words, and I thought, “Maybe I’m not in love with Australia any more.”’

And even more so back in 2015, when the ex-son-in-law was asked, the day after he had been appointed England coach, how he would feel preparing a team to beat the Wallabies.

‘I didn’t divorce Australia,’ he answered. ‘Australia divorced me.’

1

LARPA BOYS

Eddie Jones was nine years old when he first saw the face of racism up close. Eddie had always known he was different, but he lived in a rarefied little world where everyone was different, and that difference was embraced rather than suppressed or rejected.

But not on this day in 1969, with his father away with the Australian armed services in Vietnam and his mother left alone with Eddie and his two sisters at their home in the Sydney southeastern suburb of Little Bay.

It was customary for members of the local Returned Services League to help out the families of soldiers serving overseas. A roster would be drawn up, and RSL members, many veterans of conflicts in the Second World War or Korea, would arrive unannounced for a few hours’ gardening or handyman work. Eddie remembers well the day a man from the RSL pushed a lawnmower up their garden path.

When Eddie’s Japanese mother opened the front door, the man took one look at her, growled, ‘I’m not mowing your lawn,’ and headed back down the path. Eddie’s mother shrugged, said calmly, ‘Looks like we’ll have to mow our own lawn,’ and shut the door.

It wouldn’t be the last time Eddie would be subjected to racist attitudes or slurs. He would hear them from time to time on sporting fields around Sydney, but like his mother he learned to stay calm and move on.

‘If she had said, “Oh, they are racist,” then it would have been embedded in me, but it wasn’t,’ he says. ‘I never grew up feeling isolated. My mother was dead against us having any sort of Japanese characteristics because of the environment, so we were brought up dinky-di Aussies.’

Eddie’s father Ted was a career soldier who had served as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces in Japan after the Second World War. It was there that he met Nellie, who was working as a translator at BCOF headquarters at Eta Jima, 8 kilometres west of the major port of Kure. Having spent much of her life in the US, Nellie spoke perfect English. Her father had moved from Japan to California before the war and established an orchard in the Sacramento Valley. The future looked bright in his new country, and then came 7 December 1941 and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Nellie’s family, along with an estimated 120,000 other US residents of Japanese descent, were rounded up and relocated. The fruit in the orchard rotted on the trees as for four years they were split up and shunted between a series of internment camps. Nellie’s father never went back to California. At war’s end, angered and humiliated by the treatment they had received at the hands of the US authorities, he returned to Japan and arranged for his family to join him.

By then twenty-one years old, Nellie had to learn a new culture and a second language all over again. She may have looked Japanese, but her life experiences and thought processes were very much American. It made assimilation difficult, but her knowledge of western ways and language skills made her a valuable acquisition when she began work at BCOF headquarters. It also made it easier for her and Ted Jones to communicate and fall in love.

Fraternization between members of the occupying forces and local girls was inevitable and, while officially frowned upon, the longer the occupation lasted, the more accepted it became. But the sight of Australian servicemen walking down the street or dining with Japanese women in Kure was one thing. The idea of them marrying, and returning to 1940s Australia, quite another altogether.

When Australian forces arrived in Kure in 1946, many straight from the former battlefields of the Southwest Pacific, Australia was still reeling from four years of bitter conflict with the Japanese. Newsreel vision of returning prisoners of war being stretchered off ships in shocking physical condition, and newspaper reports of the cruelty and deprivation they had been subjected to at the hands of the Japanese, were still very fresh in the minds of the Australian public. Over the ten years that the occupation continued, the attitudes of many of the occupying soldiers towards the Japanese may have mellowed, but for many back home they remained as bitter and intractable as ever.

In October 1947 Corporal H. J. Cooke became the first Australian soldier to apply for permission to marry a Japanese bride and bring her back to Australia when his deployment ended. In rejecting the application, Australia’s minister for immigration, Arthur Caldwell, spoke for many of his countrymen when he said, ‘It would be the grossest act of public indecency to permit a Japanese of either sex to pollute Australia.’

By the time Ted and Nellie made their application to marry, the prevailing attitudes had softened. The peace treaty between the Allied Powers and Japan was signed in September 1951, and seven months later legislation was passed in the Australian parliament to allow Australian servicemen to bring their Japanese wives and children home to Australia.

The first to do so was Sapper Gordon Parker, who arrived with his wife Nabuko, known as Cherry, and their two children in June 1952. By the time the last Australian occupying troops left Japan in November 1956, another 650 couples had joined them, including Ted and Nellie Jones.

In 1960, Ted, Nellie and their two daughters, Diane and Vicky, were living close to the city of Burnie, Tasmania, as Ted worked at Kokoda Barracks in nearby Devonport. It was at Burnie, on 30 January, that Eddie was born. Soon afterwards Ted was posted to Sydney’s Randwick Barracks, and the family moved to Little Bay, a working-class suburb in the Randwick municipality. Bounded by Matraville, Malabar and Chifley, it is also a short walk to La Perouse, a bayside suburb that would have enormous significance for Eddie and the sport of rugby union itself.

Although it was only a few minutes’ drive to some of Sydney’s most expensive waterfront suburbs, La Perouse was far from affluent. In fact, it has been described as ‘Sydney’s Soweto’. Known as ‘Larpa’, in the early 1800s it became a dumping ground for the city’s Aborigines, who were herded together in a government-run mission to keep them isolated from the fast-growing white settlement. As the years went on, Aborigines from country areas who came to the city would also gravitate to Larpa and live in crudely built shacks and lean-tos outside the mission gates.

Among these non-mission families were Gordon and May Ella and their twelve children, including twin boys Mark and Glen – born in 1959 – and brother Gary, younger by one year. Like the dozens of other youngsters growing up in Larpa, the Ellas were active, spirited and sporty. They made their own fun outdoors, on the streets, playing in spare lots and fishing or swimming in the bay. They had little choice. Their ramshackle two-bedroom home was not a place in which to spend time. It had no hot running water or sewerage connection. There were only two power points, and the family would bathe outside in a copper tub using water heated in a kettle. Cooking was done on a fire stove fuelled with wood collected by the children from nearby scrub. The family ate in the kitchen, so small that meals were served at the four-seat table in shifts, and Mark, Glen and Gary slept together on a single mattress on the floor of their parents’ bedroom.

It was a world devoid of comforts, but full of family, friends and fun, a world that seemed like boy heaven to Eddie Jones, and one that the Ellas were more than happy to share.

The day that Nellie took five-year-old Eddie a few minutes’ walk to the local pre-school would prove to be one of the most fortunate of his life.

‘I was very lucky,’ he says. ‘The first day I went to kindergarten at La Perouse, sitting next to me on the mat were the Ella brothers, three of the greatest athletes ever to play rugby. They changed the way the game was played and the expectation of how it could be played.’

For the next thirty years in local junior teams, then at La Perouse State School, Matraville High School and Randwick Rugby Club, Eddie would have a front-row seat as the Ellas put on a show those lucky enough to witness it will never forget. He saw them do things with a rugby ball in their hands never done before or since – much as Eddie has tried to replicate it in the teams he coaches.

‘That’s always been my dream, to go back to those days and to see the game played the way they played it.’

Rugby union would bring Eddie and the Ella brothers fame and – in his case – fortune, but it wasn’t the only game that they played together in the early days. In fact, it wasn’t even their major sporting interest.

‘Rugby league was probably our favourite back then,’ says Glen Ella, whose uncle Bruce ‘Larpa’ Stewart was an exciting and popular league player for South Sydney and Eastern Suburbs in the 1960s. Stewart also played A-grade league for the La Perouse All Blacks, and it was the ambition of every Larpa youngster to do the same.

The Ellas, and Eddie, played junior rugby league for La Perouse on Saturdays, and union for Clovelly Eagles on Sundays.

‘Whatever we were into, he was too,’ Glen says. ‘Union, local league, cricket . . . and we were always playing touch footy. Whenever and wherever we could we’d be playing touch; on the oval, on the asphalt playground at school, it didn’t matter. If we had a ball we’d use it, if we didn’t, we’d use a can or a bottle or something.’

In summer the sport of choice was cricket, and it was as captain of his local junior team that Eddie first began to show the character traits for which he would become renowned.

‘I probably spent the most time with Eddie in the early days because even though all four of us were in the same grade at school, Mark and Glen were older,’ says Gary Ella. ‘That meant I was in the same age group for local sports as Eddie. He was very popular because his Dad had a car, and he’d drive us to all the games. He seemed pretty quiet when we first met him, but that’s probably because he was concentrating more on his studies than us. He was always smart, and not just in the classroom. He was a smart footballer, a very clever dummy-half at rugby league for La Perouse and a good flanker and then hooker at rugby, but cricket was where he really came into his own.

‘He was captain, opening batsman and off-spin bowler for our junior side and as captain he took it very seriously. He was always a thinker, always a planner. We were playing in a local suburban competition, so you’d play against the same kids a lot. Eddie would work out their strengths and weaknesses and have a game plan to beat them. The rest of us would just show up for a game, but Eddie would have it all mapped out. He knew exactly what he wanted us to do.’

And if they didn’t do it, he’d let them know about it.

‘That was when the sledging started. He was so quick-witted, and the sarcasm would come out. Eddie’s never been too scared to let people know what he thinks, and it wasn’t just the players on the other sides. Eddie would always put himself in the most difficult position. He’d be the one fielding closest to the bat. That way he could get into the opposition batsmen’s face, but if someone in our team did something wrong he’d let them have it too.

‘That’s just the way he is. If he puts the time in, he demands it of others.’

While he and his friends continued to play cricket throughout their school days and, in Eddie’s case, beyond (he joined Randwick Cricket Club and rose through the grades to the Second XI), rugby union would usurp rugby league as their major sport once they started at Matraville High School in 1972.

At the time, rugby union in Sydney was seen very much as a blue-blood sport, with its roots firmly in the private-school system. Then an amateur code, unlike professional rugby league it offered no financial incentive and so was not considered an attractive sporting option for young men of limited means.

And Matraville High was a school full of young men of limited means. With its proximity to La Perouse, the school had a high percentage of Aboriginal students. A cruel and racist joke of the period suggested that when the boys graduated from Matraville High they could simply walk straight across Anzac Parade to begin their new life at Long Bay Jail.

It was a slur typical of the prevailing attitudes of the time, with Indigenous Australians treated as second-class citizens legally and socially. The feeling of marginalization had a flow-on effect, leaving many young Aborigines frustrated and without hope. What was the point in going to school, they asked themselves, when they would never get a decent job because of the colour of their skin? From the day the school opened in 1964 truancy at Matraville High was a major problem, as teachers struggled to keep pupils motivated. The solution they came up with was sport. If the kids were keen to play in school teams, they reasoned, they would at least show up for classes.

The obvious winter sport for Matraville High to play was rugby league, with the school in the heart of the giant South Sydney Rugby League catchment area, and for the first four years of its existence that was the game it played. That changed in 1968 with the arrival of deputy principal Geoff Mould. A physical education teacher who had played both league and union in his youth, Mould was convenor of the Combined High Schools rugby union programme and so pushed for Matraville to change over to the fifteen-a-side game. It was a suggestion that did not please the school’s parents, many of whom saw professional rugby league as a way for their boys to get a start in life. There was also an element of reverse snobbery. Rugby union, they felt, was the domain of the toffee-nosed private-school set. How could little Matraville with only 900 students – half of them girls – hope to compete with rugby powerhouses like Sydney Boys’ High, Cranbrook, North Sydney Boys’ High or, the grand-daddy of them all, St Joseph’s College, Hunters Hill?

It was a valid concern, but rather than being put off by rugby’s cultural traditions, Mould was attracted to them.

‘I found that among the various school sports, rugby was one of the few which was devoted to an amateur philosophy. The game’s traditional approach appealed to me. The old school tie can be ridiculed at times but it can also be a valuable asset.’

Mould had another reason for wanting to promote rugby union at the school. Soon after he arrived at Matraville, he was approached by Bob Outterside, coach of Randwick’s first-grade side, to help with the club’s pre-season fitness campaign. Although in his mid-thirties at the time, as he ran and worked out with the players Mould felt himself drawn back into the rugby club environment and signed up to play for Randwick in the unofficial fifth-grade competition. For two years until he finally retired from the game, Mould embraced everything that rugby and Randwick had to offer. Like many before and since, he was smitten by the club’s playing style, which relied on the backline standing flat in attack, quick ball movement through the hands, backing up and daring counterattack from anywhere on the field. Randwick’s commitment to running rugby, which earned the club the nickname ‘The Galloping Greens’, traces its origins to the legendary Waratahs side that toured the UK, France and Canada in 1927–28. Unable to call itself an Australian side because the Queensland Rugby Union had collapsed and so the game was run entirely out of New South Wales at the time, the Waratahs were led by Sydney University’s Arthur Cooper ‘Johnnie’ Wallace, who, as a Rhodes Scholar, had won rugby Blues at Oxford from 1922 to 1925, and played nine Tests in the centres for Scotland.

It was Wallace who instilled in the Waratahs the philosophy of running rugby that would thrill crowds as they won thirty-one of thirty-seven games on tour, including Tests against Ireland, Wales and France. The Test against England, in which the Waratahs came back from an 18-5 deficit to lose 18-11, was described at the time as the greatest match ever seen at Twickenham. Randwick had two representatives in the Waratahs, halfback Wally Meagher and Wallace’s centre partner Cyril Towers, who would spread the running rugby gospel with almost religious zeal on their return.

‘They actually first saw it being played in New Zealand,’ says former Randwick and World Cup-winning Wallaby coach Bob Dwyer, who played back row in first-grade sides coached by Towers.

‘Their captain, Johnnie Wallace, said, “This is the way to play the game,” and they latched onto it. They all brought it back to their clubs, but it was only Randwick that fully embraced it. When Wally Meagher died, Cyril continued to coach that style. He wasn’t the best explainer. One night at training he shouted at me, “I’ll never coach another team that you’re playing in.” When I started coaching Randwick I kept pestering him to re-explain his theories until finally one night I told him, “Okay, okay, I get it.”’

It wasn’t just first-grade players that Towers tutored on what he believed was the only way to play the game. He would carry a jar of old coins in his pocket and line them up on the clubhouse bar to demonstrate backline formations to anyone who showed an interest. One such person was Geoff Mould, who, when he introduced rugby to Matraville High, put everything Towers had taught him into practice.

It helped that amongst his small playing group he unearthed one of the greatest schoolboy talents to ever play the game.

Russell Fairfax, with blond hair falling halfway down his back and a spindly physique that suggested a decent tackle would break him in half, looked like he would be more at home on a surfboard than a rugby pitch, but appearances were deceiving. Talked into joining Mould’s first Matraville side, Fairfax was a sensation. Playing at fullback, but popping up wherever the ball was, Fairfax embraced the running rugby credo with spectacular results. In 1969 he was chosen in the first-ever Australian Schoolboys side that toured South Africa. The following year, while still at school, he was playing first grade for Randwick when picked for the Sydney representative team to play against Scotland. If any Matraville parents still had doubts that Mould was on the right track, they had only to look at Fairfax.

When Eddie and the Larpa boys arrived at Matraville High in 1972, Fairfax had moved on to bigger things, including eight Tests for the Wallabies before attracting cult-star status with the Eastern Suburbs rugby league side, but his influence remained. In four short years Matraville, in no small way through its association with the Fairfax name, was fast becoming a respected force in high-school rugby.

Schoolboy rugby in NSW is split into several groups, the major organizations being the privately funded Greater Public Schools (GPS), Combined Associated Schools (CAS), NSW Combined Catholic Colleges (NSWCCC) and government-funded Combined High Schools (CHS). Each organization runs its own competition, the most prestigious being that of GPS, but there was one tournament open to all schools in the state: the Waratah Shield. For the most part the elite GPS schools chose not to enter the knock-out tournament, but it still attracted around a hundred teams each year and was regarded as one of the ultimate school sporting competitions in the country.

As Eddie and his friends began their high-school education at Matraville, there was no question about who were the biggest men on campus. The whole school would turn out to cheer on the 1st XV each Wednesday afternoon as they knocked over one opponent after another on their way to the Waratah Shield final and, ultimately, lifting the shield for the first time.

‘They were great players,’ says Mark Ella, who would go on to captain the Wallabies in ten of his twenty-five Tests and score a try against each of the four Home Nations on the 1984 ‘Grand Slam’ Tour.

‘It was inspiring to watch them. They would run onto the field immaculately dressed in the school’s colours, and the crowd would go wild every time they scored a try. It made a big impression on us, and the only thing we wanted to do was play in the firsts and win the Waratah Shield.’

Before that could happen they had to work their way up through the age divisions. It didn’t take long for the newcomers to make their mark. When Matraville High mathematics teacher Allan Glenn looked at the motley collection of boys who showed up for the first practice of his Under-13 team, he wondered what he was getting into. When he handed them the ball and told them to throw it around, he couldn’t believe what he was seeing. At first glance they seemed an eclectic group; a mish-mash of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, shapes and sizes, but on a football field they meshed together like few school teams before or since.

The backline was made up entirely of Aboriginal players, apart from red-headed winger Greg Stores – earning it the nickname ‘the blackline with the red tip’. Outside halfback Darryl Lester were four future Wallabies in the three Ellas and silky-skilled centre Lloyd Walker. The only forward with any size was second-rower Warwick Melrose, who, like many of the team, would become a regular first-grader at Randwick. Eddie Jones was the smallest, but punched well above his weight.

‘He was small, but it didn’t faze him,’ says Glen Ella. ‘We scored a lot of tries, but you can’t do that if you don’t have possession. It was amazing how many times Eddie would go into a maul and come out with the ball.’

At a time when a try was worth four points they would regularly put fifty, sixty or more points on the opposition. Allan Glenn’s half-time speeches often consisted of little more than ‘Do you think you can double it?’, and usually they would.

Glen Ella says what they did in organized matches was simply an extension of what they had been doing in games of touch footy for years. The only difference was they now always had a football to play with instead of a can.

‘It was just basic catch and pass, use the open field. We were a small team so when we got the ball we made the most of it. The forwards would fill in like backs.’

In 1974 the NSW Rugby Union started an Under-15 version of the Waratah Shield, the Buchan Shield, named after long-time junior administrator and referee Arthur Buchan. Early in the season, Buchan was at one of Matraville’s matches. When Allan Glenn pointed him out to his players, Glen Ella marched up to him and said, ‘Hey Mister, we’re going to win your shield.’ He was right. Matraville beat St Ives High 33-11 in the final.

The shield win, played at the Sydney Cricket Ground as curtain-raiser to an Australia–England school international won 28-9 by England, did wonders for the boys’ confidence and esteem. The true personality of the once quiet, shy Eddie Jones emerged.

‘He was a ratbag,’ says Mark Ella. ‘That’s the funny thing. Everyone thinks that Eddie is so serious now, but at school level he was just as crazy as everyone else. He was probably more academically attuned than the rest of us but he was out there. There’s this image of him now being something of an outsider, a loner, but he was just part of the gang back then.

‘No one treated him any different from anyone else, and I can’t recall him copping any racial taunts when we played footy for our school. We had five Aborigines in the backline, a half-Japanese hooker and a redhead on the wing. If anyone had anything to say it was levelled at all of us, and anything Eddie copped he could give back with interest.

‘He was fairly competitive at rugby and cricket, but the biggest thing about him was his quick tongue. He’ll never die wondering. He and [former Matraville High, Randwick, Brumbies and Wallabies five-eighth] David Knox were the best sledgers I ever played with.’

But it wasn’t fear of being ‘out-sledged’ by Eddie that stopped opponents from making racist comments about him or any of his team-mates, according to Gary Ella.

‘We were winning just about everything during that period, and the opposition didn’t want to stir us up.’

It is a viewpoint that Eddie subscribes to, and one that has stayed with him.

‘I copped a little bit of racist stuff through my career. There was a game when I was playing for NSW against Queensland, and their prop called me a Chinese so-and-so. I told him, “Mate, you’re too stupid to know the difference between Chinese and Japanese.” Back then in Australia you were either white or Aboriginal. There weren’t any Asians. When you’re young you want to be liked and you have to be good at something. The only thing I could be good at was sport, and the racial thing wasn’t too bad because I came through with the Ellas. They were just unbelievable sportsmen, so we won everything, and because you are winning, you tend to get less people mouthing off. If you are winning, there’s not much that people can say, is there?’

Winning became a habit for the Matraville High teams in which Eddie played. Allan Glenn believes their for-and-against in the years he coached them would have been in the vicinity of 1000 points for, fifty against. When they graduated to the 1st XV and the coaching of Geoff Mould, the success continued. It could be argued that the natural talents of players such as the Ellas and Lloyd Walker meant they didn’t require any tutoring, but Mould refined and polished the skills they’d been born with. To do so he called on the experience of the man who knew more about Randwick-style running rugby than anyone: Cyril Towers.

Aged in his early seventies, Towers would walk several kilometres from his home in South Coogee each week to help with the team’s preparation. It was the start of a coaching education that would have a lasting effect on Eddie as he moved through the ranks at Randwick.

‘I remember Cyril coming up and helping coach my high-school team. The Ella brothers were in that side, so he had a huge part in the way we played. Then when we went to Randwick it was a natural progression.

‘Cyril coached Bob Dwyer. Bob coached me and Ewen McKenzie and Michael Cheika, and we all coached the Wallabies. Ewen moved away from the Randwick style a bit, but Michael and I have tried to stick with that flat-ball game. It’s the way we were brought up to play.’

Towers, who died in 1985 aged seventy-nine, called that Matraville High side the best schoolboy team he had ever seen. It won the Waratah Shield in 1976 and 1977, but it was an unofficial pre-season match that cemented its reputation in the minds of those who really know Sydney rugby. In the lead-up to the 1976 season Mould extended an invitation to play a trial match to the mighty St Joseph’s College.

At that time the GPS premiership had been contested on fifty occasions. ‘Joeys’ had won thirty of them and would add title number thirty-one in that season. The school has produced more Wallabies than any other, and it is compulsory for all students to attend all matches in full uniform, creating an intimidating wall of sound at their Hunters Hill oval. Few casual observers would have given the Matraville boys a ghost of a chance against the thoroughbreds of schoolboy rugby. The Joeys side that day included future Wallabies lock Steve Williams and hooker Bruce Malouf, who would keep Eddie in reserve grade when he arrived at Randwick. The Joey’s players and supporters arrived in a fleet of eight buses. Eddie and his team-mates ran onto the field wearing an odd assortment of different-coloured shorts and socks. In the crowd, getting his first look at the players he would later coach, was Bob Dwyer.

‘When I watched the two teams come out, it looked like a scene out of an American movie. We were seeing the kids from the wrong side of the tracks trying their hand against the superstars. One team ran out beautifully attired, fit and strong and healthy. Then Matraville emerged, half of them looking like members of the Jackson Five, with skinny legs and socks around their ankles.

‘While Joeys played strong, quick rugby full of initiative and aggression, the little Matraville guys would just tackle and tackle, until their opponents coughed up possession. Their approach was, bang, bang, zing, zing, twenty passes, tackle, contest, keep the ball going, try. They won by twenty points, back in the era when a try was only worth four.’

In actual fact the final score was 15-9 to Matraville, but in terms of sending shockwaves through the stodgy schools rugby community, it seemed far greater.