Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

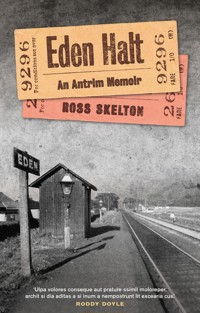

Eden Halt describes a childhood spent on a remote coast of Northern Ireland, in the shadow of the Second World War. With his father absent in the African campaign, a young Ross Skelton's constant companion is his taciturn grandfather, a UVF veteran and caretaker of the local big house. His father, Tom Skelton, returns, troubled by malaria and nightmares. An aspiring writer, with connections to Louis MacNeice in nearby Carrickfergus, and to the artist Raymond Piper, he deserts the civil service for the life of a navvy, given to sudden absences, tramping the roads and sleeping rough, as the family falls from comfort to extreme poverty. They live off fishing and beachcombing in a tiny community of wooden bungalows on the wild Antrim coast, inhabiting a 'land that God forgot'. Despite primitive surroundings, the family is highly literate, with Ross's mother an avid reader, while his father writes at night. The memoir sensitively evokes a boyhood spent in a ceaseless quest for driftwood by a sea in its restless and violent moods, escaping to the hills on his home-made bicycle and raising racing pigeons in a make-shift loft. Reconstructing a time and place long gone, its sounds, smells and echoes, Ross Skelton pieces together the fragments that constitute a life, and gave rise to his career as a psychoanalyst and writer.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

for Maya and Noah

It wasthe last psychoanalytic session with a woman patient whom I had been seeing for some time. When she had first come to my consulting room, she had been partly paralysed and unable to walk. Now, after a long analysis, she was able-bodied and fully mobile again. As I rose to show her out, she turned and spoke: ‘I must say I never really cared for you.’ She paused and, as she closed the door behind her, added, ‘But you certainly knew what you were doing!’

I sat down and stared idly at my bookshelves. At the top were volumes of logic and philosophy, in the middle shelf upon shelf of books on psychoanalysis, and near the bottom, at my elbow, works of literature; it looked like the layers of my life. Had I known what I was doing in all those reading phases? It seemed as if I had been sleepwalking for years, finally finding my feet as a psychoanalyst. I had studied widely diverse fields: as an undergraduate at Trinity College, Dublin, I had felt a deep need for clarity of thought and scientific certainty. Ever since I was a boy, I had been constantly infuriated by my father’s endless mysticism, speaking as he did of the Beyond as if it were a personal friend to whom only he and a few selected individuals had access. I had found a kind of intellectual home in Logical Positivism, a philosophical movement dedicated to the ‘worship’ of objectivity and rigorous logic – where philosophy aped the natural sciences. I had been delighted to discover that the logical positivists had referred to metaphysicians as ‘misplaced poets’ and religion as nonsense. Logical philosophy would have no truck with any of Father’s speculations and I had embraced it enthusiastically. In retrospect, I realized that, paradoxically, I had been greatly impressed by a Hegel lecturer whose views came suspiciously close to the mystical.

At the University of London I did graduate work on logic and the foundations of mathematics for three years, after which I was offered a lectureship in logic and philosophy at Trinity. On my return to the college in 1970, to my surprise I was told I would also be teaching political philosophy. I had been for a short while at the London School of Economics during the 1968 riots – an offshoot of those in Paris. In those exciting times I had read the anarchism of Kropotkin and the early papers of Marx and, so tailoring the course to my own interests, I began teaching what I knew. My colleagues in the Philosophy Department, though dubious of my choice of teaching material, said nothing and the course became a popular one.

It was to become a strange career at Trinity, for although I loved teaching logic and philosophy, from the very beginning I had a disadvantage: I could not write. Unable to finish my doctorate in philosophy and logic at the University of London, I soon found I was incapable of writing anything at all. No articles flowed from my pen, no learned tomes emerged; however, I did love teaching anarchism and divided my time between talking with students and doing logic proofs (a form of algebra) instead.

Over the years, working in a philosophy department, I tried several times to read Heidegger and other continental philosophers, but found that my logical training had cut deep and I was unable to sustain belief in their more literary and subjective approach. In time an appreciation of continental philosophy was to come from an unexpected quarter: I went into psychoanalysis.

I had attended the Freud lectures of Richard Wollheim, Grote Professor of Mind and Logic at University College London, and I invited him to speak on the subject at Trinity. Afterwards, over a drink, I bemoaned the fact that there was no psychoanalysis in Dublin. He directed me to a small group of Freudians known as the Monkstown Group, which I immediately joined.

Discovering psychoanalysis was like coming home (almost literally because my father had read Jung) and I quickly took to it, attending seminars night and day and becoming involved in a London group studying the logic of the unconscious. My epiphany came a few years later when I was invited to lunch with the eminent Pakistani analyst, ‘Prince’ Masud Khan. During the long lunch, he evidently pieced together the essentials of my story and in a lull in the conversation suddenly announced, in a tone reminiscent of Freud which I will never forget: ‘An academic who does not like to write?’ The question hung in the air and all at once the ludicrous nature of my position was clear to me; before we parted, he directed me to a French analyst then practising in Dublin.

In the course of that analysis I began to read the poems of Louis MacNeice – a much-admired acquaintance of my father’s. Before long I had managed to write and publish a few critical articles on his work. At that stage, I had embarked on part-time training as a psychoanalyst at St Vincent’s Hospital in Dublin and was slowly becoming conversant with the highly subjective and intuitive aspect of that mental discipline, poised, as it is today, between the neurosciences and literature. To practise clinically I had to learn how to suspend the conscious logical method in which I had been trained and reserve it for college lecturing. The clinical course was dominated by the theory and practice of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who had been deeply influenced by Hegel. Ironically, I had come full circle – almost like a return to the father, for Hegel, while immensely insightful in rational terms, has a mystical core, believing as he did that AbsoluteGeistor Spirit comes to know itself only by the evolution of our human life-world. As Hegel puts it: ‘The owl of Minerva only spreads her wings with the falling of the dusk.’ – that is, the truth of our lives can be seen only by looking back. We travel hopefully in life, encountering successes and failures, but it is only when looking back that we can see what was important. In fact, a central tenet of psychoanalysis is that whereas we live our lives forwards, we understand what Freud called ourpsychicalreality in memoir.

By this time, my interest in Freud was becoming dominant and, disenchanted with the endless arguing of philosophers, I decided to start a Freud study group. But who would come? My landlady, who coincidentally was in analysis, said she would attend; so I had one participant. Then she suggested that her friend could come and when I asked if the friend was interested in Freud, she said she didn’t know but the friend was unemployed and needed something to do. Reluctantly, I agreed and we began reading and discussing once a week. Before long, one or two philosophy students joined us and each week the group grew until one day the then head of department, wondering where his class had vanished to, went in search of them only to find most of his students crowding my office. The group had become so popular, he suggested I start a new course of my own called Existentialism and Psychoanalysis. This eventually gave birth to a master’s in Psychoanalysis at Trinity and paved the way for a clinical course based in St James’s Hospital Department of Psychiatry in Dublin.

I was still a reluctant writer and struggled on until one day I received a letter from Edinburgh University Press offering me a contract to compile an encyclopaedia of psychoanalysis. I jumped at this opportunity and put myself to work in my office – a shed at the bottom of the garden. With a view of white fantail pigeons, commuting from lawn to dovecote to roof and back, I enlisted a team of nearly four hundred scholars and analysts from around the world.

For six years I spent three hours every morning mostly on email dealing with the flood of material that had arrived from North America through the night. By lunchtime I was drained and had to rest before going to college to teach. By the sixth year I began to feel that the book was literally killing me. One morning, my then wife (also a psychoanalyst) came down to the shed and asked me to come up to the house and look at something on her computer. On the screen was an item entitled ‘Burnout – signs of’ and a list of six danger signs. I scanned it: I had four out of six.

With this shock I started easing back from the brink by working less. But the book was near completion – the one thousand entries, covering seven schools of psychoanalysis, were nearly ready – another six months should do it. I decided to compromise. Since finishing analysis, I had begun to keep a diary that seemed increasingly drawn back to my childhood. It was becoming the high point of my day. I decided I would give myself the first hour of the morning to writing about where my imagination took me.

By the time the thousand-entry encyclopaedia was ready for publication, it had become clear that work on the book had damaged my marriage, and my wife and I separated. I had been so immersed in my work that I had not noticed what had been obvious to everyone else. With our marriage in ruins, my thoughts turned to my parents. My relationship with my parents, particularly with my father, had never been good, but now that they were dead I could not turn to them for help. Yet I kept writing what would eventually become this memoir of childhood. I now realize that every day I spent in their ghostly company was invisible mending; that finally I was beginning to understand, to love them and at last to see myself in them.

***

I was standingin my office in Trinity College, Dublin, looking out of the large window over Front Square. On the desk lay philosophy lecture notes, which I had just read over. The phone rang. The secretary told me someone wanted to speak to a philosopher. It was a few minutes before the lecture, so I asked her to send him in.

I got up, opened the door and there stood a bearded man in an old raincoat. I started – he looked just like my father. I told him to wait. After I had composed myself and showed him in, he sat down. I asked him why he wanted to speak with a philosopher and he told me he wanted to reconcile the world’s religions. As he talked, scribbling notes at the same time, it soon emerged that he had the kind of mind that connects everything with everything. I was thinking how much he reminded me of Father and my eyes must have glazed over for he suddenly became irritable.

‘I am the King of Heaven but it would take too long for me to explain this to you,’ he shouted.

I told him I would have to leave soon. Angry now, he leaned in to my face and asked me if I even knew what he was talking about.

‘I may have to kill hostages,’ he said.

I froze, but did not react. This was not good.

‘Do you know what I’m talking about?’

‘I realize that things must be difficult for you,’ I replied.

‘How do you mean?’

‘With your new ideas.’ I was wondering how to get rid of him.

‘They’re not new ideas!’ He was very angry now.

‘Well they are your modern version of ancient ideas. I really must go downstairs now.’

To my relief, he seemed mollified by this and when I reminded him again that I had to go, we rose. At the door he told me there was no way I could contact him. I wished him good luck with a sigh of relief.

I gave the lecture but kept forgetting what to say. Ending ten minutes early, I returned to my office.

At the door I heard the phone ring. I hurried in and picked it up. It was my brother, Joss, who rang only when someone had died.

‘The father’s gone, this morning at ten to eight.’

After we had finished talking, I didn’t feel anything. The examination bell began to ring. I had a cup of coffee, and then went off to give my next lecture.

When I returned, I rang home. Mother answered.

‘We’re having vegetable soup here,’ she said.

‘I wanted to ask how was it – at the end.’

‘Well, he’s gone – that’s it! We’re having soup now, me and your brother.’

‘For Christ’s sake, that’s your eldest son you’re talking to!’ I heard my brother shout in the background.

‘The funeral’s soon,’ she said.

When Ihad first learned Father was ill three years earlier, Mother drove me to Larne Hospital and we entered the stone building. Our footsteps echoed along the top corridor; in the distance I could see his bearded face in a bed facing us at the end. I stepped ahead of my mother and walked up to him. His eyes widened.

‘Christ, if you’re here, it must be bad,’ he said, looking stricken.

I felt sorry for him but at the same time I wanted to leave. Whenever I visited him and my mother, within two days I had to find some excuse to head for Dublin.

‘It’s good to see you,’ I said.

After some initial talk of doctors’ opinions, he lapsed into self-pity.

‘I’m a nobody. I’m not anyone of importance.’

‘You’re my father, that’s who you are.’

This calmed him. Now was the time to be kind. I looked out the window, filled by a large green hill, and thought of the school hymn, ‘There is a green hill far away, without a city wall’.

I glanced at the man asleep in the next bed and was told it was my old headmaster at Eden village. At this he stirred and I asked him if he remembered predicting that cars of the future would run on something the size of a nut. He did and after a brief conversation between the four of us we bade Father goodbye.

When Mother and I left the ward there were tears in my eyes. As we passed the nurses’ station, one remarked aloud that he would be a long time with us yet. In the car my mother was cheerful, glad even, talking all the time, for she had been relieved of the burden of nursing my father at home.

***

His illness progressedand he was put in a nursing home in Whitehead, a seaside town near my parents’ Islandmagee home. After some searching, I found it in a street facing away from the sea. The home, which looked like a brick cube, stood in the shadow of pine trees grouped around it. I banged the knocker and a young nurse let me into the twilight of the hall. ‘Amidst the encircling gloom,’ I thought.

Inside, in a large shabby room, the inmates were gathering to have tea. My father and I stayed back on a sofa, talking.

‘Come and eat, Mr Skelton,’ the nurse called, but he would not join the diners. Eventually I assured him I would wait and he took a place, sitting on his own at a single table. After tea the dozen or so men and women sat in a circle; I was beside Father. The others ignored our low conversation and appeared to be resting; one or two exchanged a few words. As we talked, it became plain that he hated being there and wanted to leave. However, I also knew that my mother had said she could not cope with his illness at home. He complained that although he had rewrittenFeet Over Six– his account of tramping through the six counties of Ulster – neither she nor I had sent the manuscript off to the publishers. This gave me an opportunity. I suggested that authors’ partners were often jealous of their work. This seemed to satisfy him and slowly the conversation turned to my career.

‘You’ve done well – I’m proud of you,’ he said. Those magic words – there they were at last, but after years of waiting for them, I felt nothing. Then he began to work the conversation around to his illness. I knew he had cancer, but Mother and the doctors had decided not to tell him. I looked up; everyone around us in the circle was asleep. Then he spoke of a neighbour who had died recently, adding as an afterthought, ‘but then, he had cancer’. The thought hung between us. I stayed silent. Two weeks later he was back home.

The last timeI saw my father was a year later. I had got off the train at Whitehead station and eventually found the second nursing home, a cream house with a conservatory, on the sea front. It was a quiet morning; the only sound the waves dropping on the beach, followed by the rattle of shingle.

Inside, the matron was ticking off a nurse who was standing behind a wheelchair. She turned to look at me. I asked for my father.

‘Room thirteen, first floor,’ she said. ‘Go on up – and tell him to come down and sit in the sun.’

On the landing I glimpsed my father’s back. He was sitting in an easy chair facing the light from the window.

‘How are you?’ I said brightly. He half-turned.

‘Not the worst. Your mother was in yesterday.’

‘How is she?’

‘I don’t think she wants me back at home.’

‘Perhaps if you were nicer …’

‘Too late for me to change now. She doesn’t want me there.’

I said nothing.

‘Mr Skelton, Mr Skelton! Come down and get some sun.’ It was the matron.

‘That woman won’t leave me alone.’

He stared down at his thumbs, which were resting on his thighs. We sat in silence, his clock’s red second hand sweeping.

‘It’s too late for me. It’s all too late for me now.’

‘Philip Larkin said: “Sexual intercourse began in 1963 – which was rather late for me” ’ I said, hoping to raise a smile, but he just glared at the wall.

‘Why don’t you get a bit of sun?’ I asked.

‘For what?’

‘I have to go soon.’ His face was frozen.

‘Goodbye. I’ll see you again, then,’ I said. He did not raise his head as I left.

On the island,my brother Joss drove the jeep downhill to the funeral, his wife Maggie beside him. I sat in the back. Our descent ended at my parents’ cottage, which was overshadowed by the power station chimneys on the lough shore. About twenty people had gathered at Ferris Bay harbour. Backs turned to a wind off the sea between the island and Larne port; they were watching a large ferry leaving. Outside the cottage a wooden coffin sat on trestles and a little way off stood three men inRAFuniform, one bearing a flag.

‘God, look at your mother!’ Maggie said as we got out of the jeep. ‘What a colour to wear for your husband’s funeral.’ My mother was dressed entirely in purple. My brother, stubbing out a cigarette in the dashboard ashtray, replied that at least she looked in good form. She was talking to the undertaker – a short, portly man in a top hat; he seemed familiar. I asked Joss if he was Billy Mahood from school, but was told he called himself William now. The man had a solemn moon-face and was grasping a black umbrella at chest height just below the handle.

My mother came towards us with a smile that bordered on a grimace.

‘Colour party,halt!’ We stood watching as a wind-torn, blue flag was marched by anRAFsergeant with an officer on either side up to the coffin. I hadn’t expected a military funeral for my father, though he had been a Flight Lieutenant during World WarII. It seemed strange, all this pomp and ceremony outside a cottage.

Mother was shaking the hand of a clergyman. He had a scrawny neck and quick eyes.

‘We’d better make a start, Alec,’ she said to this cousin of my father’s.

Raising one hand to the sky, the other holding a Bible to his chest, he began to speak. The group fell quiet.

‘Tom and I met in the war …’ The wind was blowing his words and, as he spoke, it grew dark. A passenger ship glided close behind him, blotting out the sky. Sheer sides towered over us as a bellow from its foghorn vibrated the ground under our feet. The clergyman’s mouth moved in silence.

‘… And Tom loved nature and he loved metaphysics …’ Far away, another foghorn called and I looked at my merchant seaman brother.

‘Did you have anything to do with this?’

He smiled.

‘I thought we should give the old bastard a good send –’

‘Atten…tion!’ roared the colour sergeant and a trumpet sounded ‘The Last Post’. A few ex-servicemen in the gathering stood to attention. Then as the Reveille sounded, notes bending in the wind, people began to shift and murmur. William, the undertaker, came over.

‘We’ll have the coffin-bearers over here,’ he called, just loud enough to be heard over the wind. My brother and I stepped forward. Tom, Joss’s pale, teenage son, looking embarrassed, came over and asked Harry, an old airman in a beret, where he should stand.

‘Hallo, Harry. A sad day for the old soldiers,’ I said.

‘Indeed it is. Indeed it is. But we gave him a good show – the Colour Party.’

‘God, I’ll soon be an old soldier myself. No trumpets for me,’ I laughed, referring to my own time in theRAF.

‘You were never in the war,’ he said, taking off his beret and then putting it back on. I went quiet. Uncle Jack, my father’s brother, who had thick glasses, joined us and took up the rear of the coffin with young Tom. Joss and I were at the front; we hoisted the coffin and moved off. I thought of him in there, my bearded father, inside that wooden box. In his life he had always been a know-all. After he died, my mother remarked. ‘Now he really does know everything!’

On one of my visits he had been in bed and, as my daughter played on the floor, he began to talk. It was only partly coherent, not unlike Lucky’s long speech inWaiting for Godot– an intellectual confession, passionate but lost. He had tried this idea and hared off after that notion, but in the end had found no answers. He ended his life perplexed.

Above us on a height, framed against the big chimneys, stood the undertaker waiting for us. Arms outstretched and coat-tails flapping in the wind, he directed us with his umbrella like a farmer guiding sheep. By his demeanour he seemed to be saying: ‘I am death and all of you belong to me.’

It began to rain. With the coffin stowed in the hearse, we headed over to the black limousine and, after helping my mother in beside Maggie, young Tom, Joss and I sat facing them in two foldout seats.

‘Did you have to wear purple?’ my brother said, ‘to the father’s funeral?’

‘ “I shall wear purple”,’ she began to recite as we stared, amazed, ‘ “with a red hat that doesn’t go, and doesn’t suit me. And I shall spend my pension on brandy and summer gloves …” ’

She went quiet. ‘Then I shall wear purple’ – it’s a poem, by Jenny Joseph,’ she said.

The undertaker, who had been waiting under his umbrella, came over and stuck his head in the window.

‘Will we go by the scenic route to the graveyard?’

We looked at my mother.

‘What do you mean, the scenic route? Where’s that?’ she asked.

‘Along the coast, so that we can remember his last journey on this earth,’ the undertaker intoned.

‘Stop your nonsense, Billy! Take the shortest way!’ she snapped.

My brother and I exchanged looks. Tom looked shaken.

‘Very well, as you wish,’ the undertaker replied and the cortège set off with him at the head. As the slow journey up the hill to the graveyard began, mother drummed her fingers on the window ledge. The only other sound was the rhythm of wipers clearing rain.

‘Are we nearly there yet? Is it far? Can you hurry it up,’ my mother said to the driver.

‘For God’s sake –’ said Joss.

The others were embarrassed.

‘Hurry up, driver. Get a move on! We haven’t got all day!’ She leant forward. I looked at the driver. Impassive, he did not register even a slight smile.

‘Behave yourself!’ Joss snapped and she subsided in her seat.

Back at the house,I started drinking and could hear my own loud laughter, which the guests politely ignored – but I felt good, knowing I should feel bad.

I went up to Father’s empty bedroom while the mourners were drinking downstairs. There was something I wanted. The door was ajar and I saw a high stool in the centre of the room. On it was a parcel – his last manuscript – tied up with string and ready for posting. This one, at least, would not be rejected because no one would send it. Writers often speak of being able to paper the walls with publishers’ rejection slips, but Father could have papered the ceiling too, as well as the outside of the house.

I was looking for what might be in his desk and, reaching into a drawer, drew out a few ledger-type volumes. Sitting down in the captain’s chair, I checked dates. A few years seemed to be missing, but after some time I located them in various places around the room, all except 1957. The year I wanted. Perhaps he had hidden it somewhere during the forty years that had elapsed. That would make sense. The more I searched, the more convinced I became that he had hidden or even destroyed the diary for that year.

I watched from upstairs as the last mourners disappeared in ones and twos back down the hill. A bit drunk, I had gone upstairs on an impulse and was now standing beside the desk. Where could the diary be? My eye fell on a green ammunition box under the bed; it was locked. I took a screwdriver from a pot of pens and pencils on the desk and levered open the box, twisting the metal lid. There it was – a royal blue diary! I stared at it, then took it out. It fell open at April. The back cover was loose. Then I saw: all the pages from September 1957 to Christmas had been torn out – the precise period I had wanted to read about.

***

Some years laterMother too died. I had been visiting Joss, on Islandmagee at his large house overlooking the Antrim coast. We were having breakfast outside with Maggie. I was gazing up the coast and across the Irish Sea towards Scotland when Joss left the table and returned with what looked like a thick paste-in book. He handed it to me saying it was Mother’s diary. I opened it at random and read what appeared to be a letter in my father’s hand.

Dearest Fuffles,

Just a few lines: we’re on the move again. Food bloody awful – corned beef and spuds (garnished with sand), marginally better than powdered egg for breakfast I suppose. The men are longing for some leave and so am I: fat chance. Battery is running out and tent blowing down. I think of you every night and hope you will soon be safe at Sunnylands.

I love you so very much.

Your Bof

Fuffles? Bof? I had never heard these names before but after reading several letters from my father in wartime I reached the astonishing conclusion that these were love letters – longing and passionate – astonishing, because for decades my parents had just seemed to hate each other.

I knew that my mother, Christine Mildred Knight, had come from a respectable Devon family. Her father was a banker and her mother was consumed by charity work. There were four sisters: Rachel, Grace, Doreen and my mother. Rachel, highly artistic, became matron to a boarding school and eventually died a Scientologist at the age of ninety-six in Florida. Grace became a model and married an inventor in South Africa. Doreen went to the Royal College of Art in London where she met her husband, Harold, another painter. My mother had set her heart on flower-arranging but her mother disapproved of her becoming a florist. Headstrong, she rebelled against her family’s world of tea and tennis and joined the wartimeRAFin 1940, where she met my father. By the age of twenty she was pregnant with me and when my father was posted abroad she had to leave for Carrickfergus, Country Antrim, to live with his parents, Ma and Pa.

For the rest of that morning I read the paste-in book and learned a great deal about those early years.

***

On 10 may 1941at sunrise, the Stranraer ferry from Scotland had steamed along the Antrim coast and into Larne Lough. ThePrincess Victoriahad been facing into a dark sky over Belfast and was closing steadily on the quietly busy harbour of Larne. It had been a good crossing for my mother, who had only heard a single burst of machine-gun fire during the night. Her career in the Women’s Royal Air Force and bid for freedom from her mother had lasted precisely seven months. When she and my father realized she was to become the mother of their child, he had applied for leave for them to get married. The Commanding Officer, a Squadron Leader Meany, not a generous man, had given them only twenty-four hours.

‘Invite me to the christening,’ he had said slyly, as Father left his office, furious that he had guessed they were marrying for the baby.

As the ship drew alongside the dock, she recognized her father-in-law from his photo. John Skelton, my grandfather, was a small, muscular man. That day he was wearing a blue suit and bowler hat. As she stumbled down the rickety gangway, she was grateful that he quickly came to her aid, took the large suitcase and led her to the waiting Belfast train.

Her diary notes that she saw a porter rolling milk churns, slanted on their edge, one at a time to the guard’s van. The carriage jolted as, with huge slow puffs, the engine pulled the carriages out from under the wooden canopy. After passing over the narrow Larne streets, they emerged from the entrails of the seaport. The train steamed through flooded marshland filled with rotting trees and on into the countryside.

They had stopped at Whitehead, a pretty Edwardian seaside resort with the waves breaking on the sand. Like Devon, or anywhere in England in wartime, the station sign was missing, leaving instead a pair of posts. Shortly afterwards they arrived at Kilroot, Dean Swift’s first parish, now a deserted Victorian brick station. One dour-looking man got off, and, wheeling his bicycle out of an archway, disappeared.

Next, the train moved slowly past a strange structure, resembling a small station. It was, in fact, a rusty corrugated iron hut on top of a kind of platform made of cinders and railway sleepers. There was no nameplate there either. This was Eden village. Behind the hut, in the far distance across the sea, was a large Norman castle.

They got off in view of the castle at Carrickfergus and, slipping through a hole in the hedge, started up a cinder avenue. They then passed through a barbed-wire military enclosure where she got a few wolf-whistles from the Canadian soldiers stationed there. Halfway up the avenue, my grandfather had to help round up some cattle and Mother went on ahead, walking towards the wooded end of the path.

In years to come, my mother never tired of telling of her reception at Sunnylands House. As she passed through the trees, she saw, on the right of the swerving avenue, a handsome ivy-covered house and, on her left, a large overgrown lawn. She approached what appeared to be the front door, in a conservatory, and pressed the ceramic button set in a dull brass surround. A bell rang far away in the house. She turned to look around and saw, some distance away, a dark figure in a hat, hunched in a wheelchair, watching her from behind horn-rimmed glasses. She was surprised at this imposing house and thought my father had exaggerated his humble origins. No one came to the door; she rang again, longer this time. Presently, through the glass, she saw a tall, thin woman in tweeds appear. She looked annoyed at being disturbed.

‘Mrs Skelton? I’m Christine,’ she had said.

‘They’re round the back,’ the woman said. ‘Go round to the back door!’

Blushing, my mother continued on round the side of the house. At home, her own mother would never even speak to a servant like that.

At the back door she got a warm welcome from her mother-in-law. Ma, a handsome imperious woman with a strong Ulster accent, introduced her to her new sister-in-law. About her own age, Sadie was working in the scullery, scrubbing potatoes over a large white rectangular sink. A brass tap was running while a Primus stove quietly roared on the draining board.

As they left the scullery, my mother had noticed long cracks in the wall from floor to ceiling, but, on entering the kitchen she felt a strong feeling of homeliness. Facing her was a big black range; there was a red glow from the grate on the right. Above it was a generous mantelpiece with a large carriage clock in the middle. At either end tall figurines held torches aloft, on the left ‘Le Jour’, on the right ‘La Nuit’. There was a framed black and white photograph of a yacht and she was told that wasThe Scamp, with which Pa had won so many cups. Her eye lit on a magnificent silver rose bowl in the centre of a polished table.

After tea, Sadie led her from the tiled kitchen into the scullery and brought her on a tour of the house. She was shown the solid wooden door of the pantry, Pa’s workshop, and then they passed a large dark space around the bottom of a long staircase. This, she was told, had been the billiard room. At the foot of the stairs were large oblong shapes covered in dustsheets. There was a crumbling harpsichord and a piano. She began idly playing the scale with one hand and Sadie was delighted they had the piano in common.

She found that her bedroom overlooked a farmyard. On the wall was a small picture of Highland cattle grazing in some Scottish glen; the hills were purple. On a Victorian washstand was a floral jug and basin. There was also a candlestick with a half-burned white candle. The candlestick was encrusted with dry melted wax. It had slowly dawned on her … no electricity.

Ma’s room had a brass bedstead with one of its pear-shaped knobs at a queer angle. The bed itself was beside a large window which had a small hole in the middle, plugged by a wad of paper. Three long cracks spread from the hole to the far edges of the window frame, beside which was a bedside table crammed with medicines.

Pa slept in an adjoining narrow room and what caught her attention was an open trunk half full of coins. She noted it was like a pirate’s sea chest. Sadie told her it was the rents which Pa collected around the town for a solicitor.

Outside the house she came upon Pa’s yacht in the byre and met Dash, his red setter gundog, who slept in the stable. Mother asked about the man in the wheelchair and was told that he and his wife, the Bates, rented the front of the house. She learned that Pa was only the caretaker and that he and his family had lived there rent-free for thirty years, ever since the owner had gone to Australia. Mr Bates was the brother of Sir Dawson Bates, a government minister, and therefore they could not be expected to live in the back of the house. She also found out that there had been a row years before: Pa had borrowed the Bates’ new axe and had lost it.

In the middle of the day she noted they ate something called ‘champ’ – mashed potato with chopped scallions and a lump of butter in the middle. It was washed down with tea. She had found it comforting and slept a little afterwards.

At four there was no cup of tea, like at home, but later Pa lit the oil lamp on the polished kitchen table and at six they had the evening meal called ‘tea’ – it was cheese on toast. Then Sadie played piano while my mother read by the lamp, thinking how romantic it all was and got ready for an early night.

Sadie handed her a candlestick with a loop handle – just like the ones in children’s stories. She said goodnight to Ma and Pa, then started up the long staircase. Halfway up, the candle flame guttered, there was a sudden noise. She hesitated. Suddenly the piano rang out in the blackness. Haphazard notes going up the keyboard, then down. Silence. She froze; the flame blew out. Sadie called down the stairs that it was only the mice in the piano.

Her bedroom door was open and there was a candlestick on the bedside table. She undressed and, folding her clothes neatly on the chair, knelt in prayer for a few seconds, then got into bed. It smelt musty and was cold but her feet found a stone hot water jar.

On her first morningat Sunnylands she was woken at six by two cocks crowing in ragged unison. Then she went back to sleep until nine. Out of bed, she washed in cold water from the floral jug on the dressing table and went down to breakfast. Ma sat at a large square polished table beside a tall oil lamp looking out at the hens in the large farmyard. Sadie was frying breakfast on the range.

They all sat at the big table with the large silver rose bowl in the middle. Ma poured tea for my mother, who blanched at how dark it was – even after milk.

‘For God’s sake you could trot a horse on that tea – give her some milk,’ Sadie had said. When my mother tasted the eggs and bacon, she pronounced this the best breakfast ever.

Pa didn’t seem to do anything except cut wood and shoot hares and plover in the fields that lay around. She soon discovered that to a considerable extent the Skeltons lived off the land. Sadie had asked her to come up the garden to get potatoes. Pa accompanied them and they watched while Sadie dug them up. She thought it was like magic, how perfectly formed purple potatoes came up out of the dark earth with the turn of the garden fork. Pa picked them out and filled her basket, for, being pregnant, bending down was too hard for her now. She liked Pa – he was kind – but she wasn’t sure about Ma. Only that morning she had been trying to light the methylated spirits in the little tray in the Primus stove. It was difficult and the match kept going out. Aware someone was looking, she glanced up to see Ma watching her efforts without offering to help.

Sadie soon taught her what she needed to learn and she became accustomed to washing potatoes and chopping vegetables, to accompany whatever Pa could shoot for the pot; mostly rabbit. As a girl, she had kept a pet rabbit in a neat hutch at the bottom of the garden, but now, when doing the washing up, she often turned round to stare at a rabbit hanging head down on the back door. For some reason they always had blood on their teeth.

Her life, like Sadie’s, was now revolving around the range, preparing and cooking broth. Since they had piano in common, the two young women got on well. Sadie, the primary school teacher, regaled her with tales of the classroom at the Knockagh school to which she cycled uphill, three miles every morning. She had a reputation for being tough but fair. In later years I met one of her ex-pupils, who remarked: ‘the softest part of that woman was her teeth’. But Sadie had her vulnerable side, for she was very keen on a man called Afie and would often cycle up to the Blahole, a windy spot above Whitehead where young people gathered, in the hope of meeting him. But Afie seemed uninterested and on the rebound she began dating a soldier stationed at the camp down the avenue.

During this period of the pregnancy, Mother occupied her evenings writing and pasting in topical clippings from the papers to make a diary-cum-scrapbook. One entry shows on the left page a photograph of a young woman scrubbing a floor on her hands and knees. On the facing page is a ballerina resting on the floor. The two young women are kneeling in the same way: on the left the ballerina, on the right the skivvy. It was clear Mother had been contrasting what she had once dreamed of being with what she felt she had now become. Odd memories occur in the diary too, like the day she got soaked in Belfast buying a Gor-Ray skirt, but mostly it was about missing dear Bof and longing for letters that often didn’t arrive.

The German bombers, en route to Belfast, always woke her at three in the morning. One night, after their engine noise had died away, she sat up in bed and wrote: ‘I hope our son has a true Irish voice, deep and grand but quick as one of their reels.’

I came a few days early; her waters had broken in the early evening after tea at six. Pa was sitting reading theNews Letterby the fire; Sadie was reading a magazine and Ma was sewing. Mother felt something shift inside her and told Ma, who told Pa to go for nurse G.

After they cycled back together, Pa settled downstairs, reading the paper by the range. There he sat while Sadie, Ma and the nurse came and went, giving him bulletins on the candlelit birth, which had not begun until three in the morning. At dawn, my mother told me, I came into the world to the ragged crowing of the two cocks and the dawn chorus.

Nurse G pronounced me a hefty infant and since I had started bawling, remarked on my lusty lungs. She began washing me in a shallow bowl, as Mother lay back exhausted, listening to water run off my skin and back into the bowl. The birdsong died away gradually and soon she was holding me and looking into my eyes as the morning sun lit the walls of the room. Eleven days later, there was an air raid and we all had to go downstairs. My mother wrote how she sat with Pa, Ma and Sadie, who held me as they huddled together under the staircase with the bombers roaring over the house.

From early on, Ma always liked to wheel my pram and, as I grew, she would often pick me up. But what annoyed Mother most was that, as time wore on, Ma took me into her bed in the morning. One day she woke and, finding me gone, rushed to Ma’s room: there she found us sitting up in bed together. Ma was feeding me with a teaspoon. But it was the way I looked over at her, she wrote, as if to say: who are you? She felt defeated by Ma and determined to leave. And she did. For the remainder of the war she and I lived with her sister Doreen in Surrey. Later we moved to a caravan behind a pub at Trodds Lane in Surrey where Mother helped in the bar.

My main memory from that time was a rare visit from Father, who put me out to play while presumably he and Mother spent some time alone together. While I was playing outside, a pig burst through the hedge and my cries brought Father rushing out to see what was wrong. He just laughed and Mother picked me up. Another time the publican, who was cutting the hedge with a billhook, let me, a five-year-old, have a go and I promptly cut my finger to the bone. Mother seems to have been very angry about this but as the Allied victory was imminent, we went back to Sunnylands to await Father’s return from the war.

One day Mother was in the scullery at Sunnylands when there was a knock at the door. Outside stood a man in uniform and, without waiting to look at him or ask what he wanted, called back over her shoulder to Sadie that it was just another soldier looking for water.

‘You bloody fool, it’s me!’ the soldier had snapped. It was my father, so sunburnt and emaciated that she had not recognized him.

When I saw him, apparently I opened my mouth and bawled for I had no idea who this stranger was. He, in his turn, no doubt traumatized by war, was perplexed by my reaction and probably felt helpless. In retrospect, it seems that on the day of Father’s return, our relationship had got off on the wrong foot.

***

From the ages