Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Elizabeth Wydeville, Queen consort to Edward IV, has traditionally been portrayed as a scheming opportunist. But was she a cunning vixen or a tragic wife and mother? As this extraordinary biography shows, the first queen to bear the name Elizabeth lived a tragedy, love, and loss that no other queen has since endured. This shocking revelation about the survival of one woman through vilification and adversity shows Elizabeth as a beautiful and adored wife, distraught mother of the two lost Princes in the Tower, and an innocent queen slandered by politicians.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 552

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ELIZABETH

ENGLAND’S SLANDERED QUEEN

About the Author

Arlene Okerlund is Professor of English at San José State University in California. She first encountered Elizabeth Wydeville, the mother of the two princes murdered in the Tower of London, in Shakespeare’s Richard III. When she discovered that this queen’s notoriety as a low-born, calculating, greedy and arrogant woman originated in slander spread by enemies, Professor Okerlund determined to expose the lies and to restore this Queen’s reputation.

England’s Forgotten Queens

edited by ALISON WEIR

Series Editor

Alison Weir has published eleven books: Britain’s Royal Families, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, The Princes in the Tower, Children of England, Elizabeth the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry VIII: King & Court, Mary Queen of Scots & the Murder of Lord Darnley, Lancaster & York: The War of the Roses, Innocent Traitor: A Novel of Lady Jane Grey and Isabella, She-Wolf of France, Queen of England. She is at present researching for a book on Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt. Alison Weir’s chief areas of specialism are the Tudor and medieval monarchies. She has researched every English queen from Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror, to Elizabeth I, and is committed to promoting the studies of these important women, many of whom have been unjustly sidelined by historians.

Published

Arlene Okerlund, Elizabeth: England’s Slandered Queen Michael Hicks, Anne Neville: Queen of Richard III

Commissioned

Patricia Dark, Matilda, England’s Warrior Queen

Further titles are in preparation

ELIZABETH

ENGLAND'S SLANDERED QUEEN

ARLENE OKERLUND

This book is dedicated to

Cynthia P. Soyster, the student and friend who first provoked my passion for Elizabeth Wydeville.

Elizabeth Van Beek, a teacher who inspires students to study and love history.

Linda Okerlund, my daughter whose wit and achievements keep me humble.

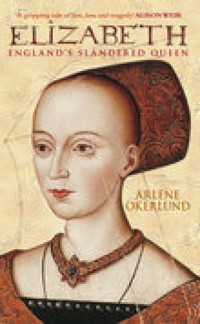

Cover illustration: Elizabeth Wydeville, by permission of the President and Fellows of Queens’ College, Cambridge.

This edition first published in 2006 by Tempus Publishing

Reprinted in 2009 by The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2014

All rights reserved © Arlene Okerlund, 2009, 2014

The right of Arlene Okerlund to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5984 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

1The Widow and the King

2Edward’s Decision to Marry Lady Elizabeth

3The Truth About the Wydevilles

4The Cousins’ Wars

5Consternation and Coronation

6Setting Up Housekeeping

7Marriages Made in Court

8The Queen’s Churching

9Fun, Games and Politics at Court

10Enemies Within

11War Within the Family

12Elizabeth in Sanctuary

13York Restored

14Problems in Paradise

15Life at Ludlow

16War and Peace

17George, Duke of Clarence: Perpetual Malcontent

18Anthony Wydeville: Courtier Par Excellence

19The Queen’s Happy Years, 1475–1482

201483 Begins

22The Mother v. The Protector

22A Woman Alone

23Queen Dowager Elizabeth

24Legacy

Genealogical tables

1The Wydevilles

2The House of York

3Lancaster, York and Tudor Connections

4The York-Neville Connection

5The Lancaster, Beaufort and Tudor Connections

6Elizabeth Wydeville Descendants

Charts

Timeline: Edward IV and the Wydevilles

The Wydeville Family

Wydeville Marriages

The Cousins’ Wars: Battles and Events

Children of Elizabeth Wydeville

Abbreviations

Notes and Citations

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Any student of historical biography stands shakily on the shoulders of preceding scribes and scholars. When writing about the fifteenth century, one discovers that truth is particularly tenuous. Most of the original documents are partisan in nature, reflecting both the bias of the writer and the opinions and prejudices of the informants. A modern biographer must piece together conflicting versions of the same event, provide coherence where information is missing, and develop a perspective guided by a sense of historical and psychological plausibility.

All authors are dependent on other scholars who have spent long, dusty hours deciphering the faded squiggles of documents handwritten centuries ago in idiosyncratic styles. Only after these source materials have been edited and published do they become available for analysis and synthesis by others. Thus, every scholar listed in the bibliography contributed to this work, but I must offer special gratitude to Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs for their meticulously researched articles about Elizabeth Wydeville. Since much of their research was published by the Richard III Society, the members of that organisation deserve special appreciation for promoting ‘in every possible way’ research and scholarship about the fifteenth century.

Above all, this book could not have been written without the assistance of librarians. Most especially, I am indebted to the interlibrary loan staff at San José State University, who produced fifteenth-century texts and facsimiles otherwise unavailable in this future-focused Valley of Silicon: Cathy Perez, Kara Fox, Shirley Miguel and Elena Seto. Special thanks also go to Stephen Groth and Judy Strebel in Special Collections; Judy Reynolds, English and Foreign Languages Librarian; and Florie Berger, Adjunct Librarian.

Librarians at the Huntington Library in San Marino also offered ready and efficient assistance: Susi Krasnoo, Mary Robertson, Steve Tabor and Mona Shulman.

I particularly thank everyone in the United Kingdom who warmly welcomed my research efforts and provided a sense of local history. Once again, my list of indebtedness begins with librarians and curators: Christine Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of the Muniments, Westminster Abbey; Christina Mackwell and Clare Brown, Lambeth Palace Library; C. Salles, Library Assistant, Stony Stratford Library; all superintendants and assistants – too many to list – in the Manuscript and Reading Rooms of the British Library.

A special place in my heart is reserved for all history-loving Brits – found in every cranny of the UK, but especially: the Duke of Grafton for permission to publish ‘The Queen’s Oak’; Lord Charles FitzRoy, who facilitated the acquisition of photographs from Grafton Regis; Sue Blake, local historian, and Peter Blake, keykeeper of St Mary the Virgin’s Church at Grafton Regis, for inviting me into their living room to discuss history over tea; David and Rosemary Marks of Potterspury, who drew a map and provided directions to Queen’s Oak Farm and the famous tree under which Elizabeth Wydeville changed history; Jill Waldram and Alison Coates, heritage wardens at Groby, who opened their homes and their books about the Greys of Groby; Juliet and Michael Wilson, churchwardens at Fotheringhay, and their two dogs (one an overnight guest), who led me up into the tower above the bells of St Mary and All Saints and down into the vault below the church floor, all the while narrating the history of Fotheringhay; Robin Walker, assistant bursar, Queens’ College, University of Cambridge, who guided me through the Old Court that Elizabeth Wydeville visited; and Peter Monk, curator, Ashby-de-la-Zouch Museum, whose boundless enthusiasm for the history of the Hastings family is infectious.

Back at home, colleagues helped translate medieval texts: Sebastian Cassarino (Italian); Marianina Olcott (Latin); Danielle Trudeau (French); and Bonita Cox (Latin and French). Jean Shiota in Academic Technology provided essential computer assistance when my own technological expertise faltered. Other colleagues read the first inchoate manuscript and provided invaluable suggestions for improvements: Cynthia Soyster, Helen Kuhn, Judy Reynolds, Susan Shillinglaw, and Bonita Cox.

Without publishers, of course, history would never be transmitted from one generation to the next. Tempus Publishing and Jonathan Reeve assure that British history continues to thrive with twenty-first-century vigour. In selecting Alison Weir as general editor of their series of books about medieval queens, Tempus Publishing is adding a significant new dimension to historical research. Had I been offered my choice of historians to evaluate my manuscript, I would have chosen Alison Weir, whose books I have read and admired for years. I have benefited greatly from her graciousness in encouraging other authors, her acuity in correcting errors, and her generosity in providing dates and facts that augmented my own research.

Historical knowledge depends on the collective efforts of those who treasure the past as a way of comprehending the present. A great tradition of scribes, scholars, curators, librarians, writers, editors and publishers has made this biography possible.

Foreword

Elizabeth Wydeville is one of the most fascinating and enigmatic figures in English history. She became the wife of Edward IV, and was the first English Queen whose marriage was made for love – or possibly lust – rather than for reasons of state, a circumstance that caused great scandal. She was also the grandmother of Henry VIII, and – more poignantly – the mother of the two princes in the Tower, Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, who were imprisoned in that fortress by their uncle, Richard III, and were never seen again.

Elizabeth Wydeville was one of the great beauties of her age, and by the clever use of her charms she ensnared its greatest womaniser, Edward IV. She lived through one of the most turbulent periods in English history. Yet her character is an enigma. Was she the scheming adventuress portrayed by contemporary writers, or is the truth rather different? It is possible that she has been grossly maligned by chroniclers and historians alike.

In this comprehensive and brilliantly detailed new biography, Arlene Okerlund presents a fresh and thought-provoking assessment of Elizabeth Wydeville. Her findings may prove controversial, but they will not fail to stimulate and engross the reader, nor to engage the emotions. For, as the author points out, Elizabeth’s story is constantly marked by tragedy and loss. Arlene Okerlund unfurls this sad pageant with vivid clarity, re-evaluating every aspect of Elizabeth Wydeville’s life and triumphantly crafting a three-dimensional portrait of a remarkable and much-misunderstood woman.

Alison Weir

The purest treasure mortal times afford Is spotless reputation; that away, Men are but gilded loam, or painted clay.

William Shakespeare, Richard II (1.1.177-79)

CHAPTER ONE

The Widow and the King

The newly widowed Lady Elizabeth Grey, née Wydeville, watched Edward IV, King of England, ride through the woods in the midst of his courtiers. Tall, handsome and already a bit hedonistic at the age of nineteen, Edward IV was celebrating his victories during the bloody and brutal Wars of the Roses. Loving the hunt, he had come to Whittlewood Forest in Northamptonshire for a holiday after his decisive victory at the battle of Towton. The royal hunting preserve near Stony Stratford lay close by the Grafton manor of Elizabeth’s father, Richard Wydeville, Lord Rivers.

Recent battles had been particularly bloody in these wars between cousins. The Lancastrian troops of King Henry VI and his wife Margaret of Anjou had killed Edward’s father, Richard, Duke of York on 30 December 1460, and spiked his head on a pole above Micklegate Bar in York to warn other rebels of the fate of traitors. The paper crown placed atop the Duke’s head to taunt his royal aspirations did little to deter his eldest son, Edward, Earl of March from taking up his father’s cause, commanding the Yorkist banner, and continuing the fight against the House of Lancaster.

The year 1461 brought more bloodshed, with battles seesawing across the English countryside. Edward’s Yorkist victory at Mortimer’s Cross on the border of Wales on 2 February was followed by a Lancastrian triumph at St Albans, just north of London, on 17 February. But when the Lancastrians failed to take control of London itself, Edward marched into the city where his charismatic vigour and the people’s hatred of Margaret’s marauding army allowed him to declare himself king on 4 March. Then he marched his army north to Towton, where the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil ended in a Yorkist victory on 29 March. As Henry VI and Queen Margaret fled to Scotland, King Edward IV headed to London to celebrate.

How ironic that this newly proclaimed Yorkist King would stop to hunt at his royal preserve near the Wydeville home of Grafton manor. The Wydevilles were staunch Lancastrians, prominent and intimate members of the courts of both Henry V and Henry VI. Lady Elizabeth’s grandfather had been ‘Esquire of the body’ to Henry V, and her father, Richard, had been knighted by Henry VI in 1426. Created Baron and Lord de Rivers in 1448, his service in fighting the Yorkist rebels had contributed significantly to Lancastrian success – until the bloody battle of Towton.

Elizabeth’s mother, Jacquetta, had first married John, Duke of Bedford, and brother of Henry V. After Bedford’s death, Jacquetta married Sir Richard Wydeville, but she retained her title as Duchess of Bedford and her status as the first lady of England until the marriage of Henry VI. When Henry VI contracted to marry Margaret of Anjou, the Wydevilles were sent to France to help escort the fifteen-year-old bride to England. Thus began a long friendship between Jacquetta and Queen Margaret. Jacquetta, the daughter of Luxembourg nobility, and Margaret of Anjou shared continental ties that bound them together in this new and different land of the Angles. No wonder that Jacquetta’s firstborn, a daughter named Elizabeth, entered service with Queen Margaret and married into another prominent and landed Lancastrian family, the Greys of Groby.

On 17 February, however, Elizabeth’s husband, Sir John Grey, was killed at the battle of St Albans, while leading the Lancastrian cavalry as its captain. Elizabeth, at the age of twenty-four, found herself a widow with two small sons, Thomas, aged six, and Richard, five. Even worse, the lands given by her husband as part of their marriage contract were in legal dispute, depriving her of income. She had moved from her husband’s large estate at Groby to return to the warmth of the home where she grew up at Grafton.

Even here, her situation was perilous. Despite the bucolic peace of Grafton manor and the emotional support offered by her large, close-knit family, a word from the new monarch could attaint both the Wydevilles and the Greys. In May 1461, the King had issued a commission to confiscate all the possessions of Richard Wydeville.1 Given the ferocity of the recent fighting, forgiveness seemed unlikely. The widow’s future under the new Yorkist King could not have looked more bleak.

But Elizabeth was not without assets. Her beauty, her charm and her cultured background placed her among the most fortunate of women. Besides, she was smart. When she heard that King Edward IV was hunting nearby, she devised a meeting where she might, in time-honoured tradition, request a boon of the King, a judgement that would restore her dower lands.

Elizabeth knew well the propensities of the nineteen-year old King, since their families had shared political and military ventures for decades. Her father, Sir Richard Wydeville, and Richard, Duke of York were knighted by Henry VI at the same ceremony in 1426. Sir Richard Wydeville had joined the Duke of York’s French retinue at Pontoise in July 1441, just months before Edward was born at Rouen on 28 April 1442.2 Mary Clive speculates that Jacquetta might even have been in the Duchess of York’s room when Edward IV was born.3

The small world of English nobility placed the two families in close proximity, especially when the Duke of York served as Protector during Henry VI’s bouts of insanity. In February 1454, York brought his twelveyear-old son and heir to the Parliament at Reading to learn about politics first hand. The adolescent Edward, then Earl of March, surely observed more than political ceremony at the various court affairs. Among the Queen’s attendants, the sophisticated Elizabeth, an ‘older woman’ with the savoir faire of a seventeen-year-old beauty, must have ignited Edward with all the passion typical of adolescent boys.

At Grafton, Elizabeth was on home territory. The Wydeville manor lay within a mile of Whittlewood Forest where the King was hunting. Having grown up here, Elizabeth knew the course that the hunters would take, the fields where the deer would be chased for the kill, the grassy spots ideal for picnics. Choosing a large oak tree, she stationed herself and her two small sons beneath it and waited. Hard in pursuit of prey, Edward saw the beautiful young mother with her children, pulled his horse up short, and marvelled at the bucolic tableau.

Thomas More describes the encounter of Edward and Elizabeth:

This poor lady made humble suit unto the King that she might be restored unto such small lands as her late husband had given her in jointure. Whom when the King beheld and heard her speak, as she was both fair and of a good favour, moderate of stature, well made and very wise, he not only pitied her, but also waxed enamoured on her. And taking her afterward secretly aside, began to enter in talking more familiarly.4

But Elizabeth knew well the ways of men, as More takes great delight in recounting:

Whose appetite when she perceived, she virtuously denied him. But yet did she so wisely and with so good manner, and words so well set, that she rather kindled his desire than quenched it. And finally after many a meeting, much wooing, and many great promises, she well espied the king’s affection toward her so greatly increased, that she durst somewhat the more boldly say her mind… And in conclusion, she showed him plainly that as she knew herself too simple to be his wife, so thought she herself too good to be his concubine.5

Some critics dismiss More’s tribute to Elizabeth’s virtue as nothing more than Tudor propaganda, since some of his information came from John Morton, who served Henry VII (Elizabeth’s son-in-law) as Archbishop of Canterbury and as Chancellor. More himself was in service to Henry VIII when he wrote The History of King Richard the Third. Yet decidedly non-Tudor sources tell similar stories about the encounter and Elizabeth’s virtuous actions.

Antonio Cornazzano, a minor Italian poet, romanticised Edward’s courtship of Elizabeth in ‘La Regina d’ingliterra’, a poem written sometime between 1466 and 1468 and published as a chapter in De mulieribus admirandis. While the poem contains many errors of fact, its dramatic homage to the widow’s virtue indicates that her fame had spread to northern Italy soon after her marriage to the King. In Cornazzano’s poem, Edward attempts to seduce Elizabeth, who had appeared at his court as a reserved, shy, retiring lady. Her modesty only inflamed the King, of course, who ordered her father to force his daughter to submit. Her father begs her to acquiesce to the King’s pleasure, but she refuses – causing her father and his sons to be banished from the kingdom. Her mother, who also begs her to comply with the King’s demands, is frustrated to the point of saying that she wishes her daughter had died at the moment of birth.

With her mother in tears, Elizabeth regrets the anguish and distress she has caused her family and finally agrees to be presented to the King. But she stands before the King not as a ‘meretrice’ (prostitute), but as an ‘immaculata una phenice’ (a pure, perfect, rare human being). She kneels before him and begs ‘una gratia’ (a gift from his Grace). The affable King tells her that he would give her the tallest mountain or make Antarctica navigable or pull out Hercules’ columns, and swears that he means what he says.

At that point, the lady presents the King with a knife she had hidden under her dress and says:

I implore you, my dear Lord, to take my life: this is the ‘gratia’ that I want from you, because, since I will lose what makes a woman live in glory, I want my soul to leave my body… Think, my Lord, King of Justice! Your vain pleasures will soon be over, but I’ll remain in eternal filth and squalor… To be your wife would be asking too much. Let me then live and die on my terms and may God save you in a peaceful Kingdom.

The King, amazed at the lady’s words and actions, becomes still and silent like a statue. He leaves the knife in her hands, takes a gold ring from his finger, lifts his eyes to heaven and says: ‘God, you be my witness that this woman is my wedded wife.’6

If Cornazzano’s idealised romance contains more fiction than fact, the story of the dagger was repeated almost twenty years later when Dominic Mancini, an Italian visiting England in 1482–3 to gather information for Angelo Cato, advisor to Louis XI of France, recorded a similar version in his official report:

…when the king first fell in love with her beauty of person and charm of manner, he could not corrupt her virtue by gifts or menaces. The story runs that when Edward placed a dagger at her throat, to make her submit to his passion, she remained unperturbed and determined to die rather than live unchastely with the king. Whereupon Edward coveted her much the more, and he judged the lady worthy to be a royal spouse, who could not be overcome in her constancy even by an infatuated king.7

Adding to the Queen’s mystique, a contemporary chronicle compiled sometime between 1468 and 1482 commends Lady Elizabeth for her wisdom and beauty:

…King Edward being a lusty prince attempted the stability and constant modesty of divers ladies and gentlewomen, and when he could not perceive none of such constant womanhood, wisdom and beauty, as was Dame Elizabeth, widow of Sir John Grey of Groby late defunct, he then with a little company came unto the Manor of Grafton, beside Stony Stratford, whereat Sir Richard Wydeville, Earl of Rivers, and Dame Jacqueline, Duchess-dowager of Bedford, were then dwelling; and after resorting at divers times, seeing the constant and stable mind of the said Dame Elizabeth, early in a morning the said King Edward wedded the foresaid Dame Elizabeth there on the first day of May in the beginning of his third year…8

Thomas More, therefore, was reporting a story that was generally current in England and throughout Europe. He further writes that Edward, who ‘had not been wont elsewhere to be so stiffly said ‘nay,’ so much esteemed her countenance and chastity that he set her virtue in the stead of possession and riches. And thus taking counsel of his desire, determined in all possible haste to marry her.’9

Thus begins the modern reputation of Elizabeth, Queen Consort to Edward IV of England, as a ‘calculating, ambitious, devious, greedy, ruthless and arrogant’ woman (to quote Alison Weir’s The Wars of the Roses).10 In describing the marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth, Anne Crawford, editor of Letters of the Queens of England, more subtly demeans the Queen: ‘She was several years older than her royal husband and was generally believed to have demanded marriage as the price for her virtue.’11

‘What price virtue?’, one may well ask. Because Elizabeth refused to sell her virtue to please a King, history (or more accurately, historians) has maligned the woman mercilessly. To the majority of historians and novelists today, Elizabeth is a conniving, grasping, overreaching female, who was manipulative at best, greedy and ruthless at worst. Scholars who, on the basis of irrefutable facts, have applauded Elizabeth’s benevolence, piety and lifelong loyalty to husband, children and siblings seem to have whispered their words into the wind. Perhaps even worse, to the general public she is an unknown woman.

The slander began immediately when the marriage was announced. Enemies attacked Elizabeth as unfit for a King who could choose his bride from the daughters of European royalty. Critics sneered the word parvenu in her direction. A whispering campaign accused both Elizabeth and her mother, Jacquetta, of witchcraft and sorcery in seducing Edward. Why else would a King, the handsomest man in England, marry a widow five years older than himself?

These attitudes have infiltrated the historical record. Charles Ross, Edward IV’s biographer, accuses Edward of showing ‘excessive favour to the queen and her highly unpopular Woodville relatives’ (‘Woodville’ is a modernised spelling of the family name) and describes the Wydevilles as ‘a greedy and grasping family’.12 Michael Stroud identifies Elizabeth as ‘a social-climbing widow of the lower nobility’.13 Alison Weir succinctly summarises: ‘In his choice of wife, King Edward was “governed by lust”’.14 Hardly. Edward IV easily and frequently satisfied his lust elsewhere. He bragged about his illegitimate children before his marriage and about his mistresses afterwards. It was not lust, but love, that compelled Edward to marry Elizabeth, a love that persisted through nineteen years of trauma and tragedies that would have destroyed less devoted relationships – and lesser women.

The biographies of this remarkable woman vary in their objectivity and understanding of her life. Agnes Strickland’s Lives of the Queens of England blames Elizabeth for many of Edward’s problems as King:

…over his mind Elizabeth, from first to last, certainly held potent sway, – an influence most dangerous in the hands of a woman who possessed more cunning than firmness, more skill in concocting a diplomatic intrigue than power to form a rational resolve. She was ever successful in carrying her own purposes, but she had seldom a wise or good end in view; the advancement of her own relatives, and the depreciation of her husband’s friends and family, were her chief objects. Elizabeth gained her own way with her husband by an assumption of the deepest humility; her words were soft and caressing, her glances timid. 15

Not until 1937 did Katharine Davies provide a more balanced and less hostile judgment of Elizabeth in The First Queen Elizabeth. In the next year, however, David MacGibbon’s better-known biography repeated spurious tales that subtly demeaned the Queen, in Elizabeth Woodville: Her Life and Times (1938).

Subsequent articles should have set the record straight. A.R. Myers in 1957 proved that Elizabeth was a careful manager of money who spent less on her household and personal needs that any predecessor Queen of the previous century. J.R. Lander in 1963 cleared Elizabeth of charges that she sought prestige and money for her family through inappropriate marriages for her siblings (see chapter 7 below: ‘Marriages Made in Court’). Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs, in 1995, verified Elizabeth Wydeville’s piety and culture in ‘A “Most Benevolent Queen”‘, just one of several meticulously researched articles that refute past slanders.

Still, defamatory attacks rage on. Most egregiously, The Book of Shadows, a deservedly obscure novel published in 1996, sets its fictional stage with this demeaning and inaccurate ‘Author’s Note’: ‘The Woodvilles, as a group, were robber barons of the first order: brilliant, brave, charismatic and totally ruthless’.16 The novel depicts Queen Elizabeth as a vain, hard, harsh woman actively involved in black sorcery. Edward is a hot-blooded fool besotted with love. A fictional commissioner of the King describes the Queen: ‘She’s a very dangerous woman. No injury, no slight, no threat is ever forgotten.’17 Though historical fictions traditionally sensationalise their subjects, this characterisation is a particularly cheap shot.

Bertram Fields in Royal Blood (1998) defames ‘the ambitious and greedy Woodvilles’18 and condemns their social ‘overreaching’19 by studiously ignoring their stature and service in both Lancastrian and Yorkist courts. Cornazzano’s contemporary poem, for instance, compliments the Wydevilles by comparing them to the wealthy and influential Borromei who served the Sforzas of Milan. Fields also repeats the speculation that Elizabeth might have plotted to kill Richard III, an accusation first promulgated by Richard himself, but the source of this charge is not mentioned. More subtly but no less demeaning, Fields refers to Edward V and Prince Richard as ‘the Woodville princes’ – as if their father had no part in their begetting or nurturing.20

More recently, Geoffrey Richardson’s The Popinjays (published in 2000) characterises the Wydevilles as vain, pretentious, empty people. Richardson takes his title from Bulwer-Lytton’s characterisations in his fictional The Last of the Barons, a paean of praise to Earl Warwick – the very man who hated and executed Elizabeth’s father and brother, Warwick’s personal bête noire. As with too many of his predecessors, Richardson relies on fiction and fabrications to build his case.

Countering such inaccuracies, David Baldwin’s biography, Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower (2002), begins by objectively examining the evidence, but concludes with unsubstantiated speculations about Elizabeth’s opposition to Henry VII. Baldwin believes that Elizabeth supported the son of Clarence, a man she loathed, and Robert Stillington, the bishop whose testimony invalidated her marriage and bastardised ten of her twelve children. Such highly improbable speculations distort the final seven years of the Queen Dowager’s life during the reign of Henry Tudor, her son-in-law, and Elizabeth of York, her daughter.

Telling the true story of Elizabeth Wydeville is important not merely to disprove the slanders and retrieve her from obscurity, but to explore how history happens. Her story provides essential insights into the historical process and the creation of reputation. It reveals that errors, if repeated often enough, become facts. It shows that writers, even if they may desire to tell truth, always and necessarily present information from a limited perspective. If we study history to avoid repeating it, the story of Elizabeth Wydeville embodies a quintessential warning about the power of propaganda to pervert truth.

As one small example, a letter written on 16 August 1469 to Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan helped establish Elizabeth’s reputation: ‘The king here took to wife a widow of this island of quite low birth’. The letter’s Italian author, Luchino Dallaghiexia, accuses the Queen of exerting herself ‘to aggrandize her relations, to wit, her father, mother, brothers and sisters’. This letter perpetuates the lies about Elizabeth’s social status and the myth of her rapacious advancement of family. No one seems to notice that Dallaghiexia was a supporter of Warwick, the man who had just executed Lord Rivers and Sir John Wydeville four days earlier, even though Dallaghiexia commends ‘the Earl of Warwick, who has always been great and deservedly so’.21 In 1469, Warwick, a sworn enemy of the Queen and rebel against Edward IV, was spreading lies to promote his own quest for the throne. While the Italian correspondent should not be blamed for disseminating the propaganda of Warwick at the height of the Earl’s power, subsequent historians must be chastised for not considering the letter’s source, context and perspective.

Because such testimony has too often been accepted at face value, the negative reputation of Elizabeth Wydeville and her family grew. Lies, gossip and character assassination by enemies, both personal and political, slandered this woman who lived during one of the most troubled and violent eras of human history. In fifteenth-century England, this woman fought for family and life with intelligence and persistence against men who used swords, power and propaganda to annihilate their enemies. Her victories were few; her losses eternal.

Most famously, of course, Elizabeth Wydeville was the mother of the two princes who disappeared from the Tower of London during the reign of Richard III. Everyone knows about the two princes. Hardly anyone knows that they had a mother. Yet this mother desperately tried to save her sons from the grasp of ambitious men. The tragedy of the two princes was but one of many. Elizabeth’s few years of glory and grandeur as Queen Consort to Edward IV were framed by profound suffering and personal tragedy:

1461

The death of her first husband, Sir John Grey, killed at the second battle of St Albans. Her dowry property was challenged by her mother-in-law.

1469

The beheading of her much-loved father, Earl Rivers, and her brother, Sir John Wydeville; murders ordered by Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick (Edward IV’s cousin) and by George, Duke of Clarence (Edward IV’s brother).

1470

The exile of Edward IV, leaving Elizabeth alone in London, eight months pregnant and the sole custodian of their three daughters Elizabeth, Mary and Cecily (ages four, three and one).

1470

The birth of their first son and future King, Edward V, while Elizabeth was in sanctuary at Westminster Abbey.

1483

The untimely death of Edward IV at the age of forty on 9 April.

1483

The execution on 25 June of her cultured and scholarly brother, Anthony Wydeville, Earl Rivers, and her son, Sir Richard Grey (murders ordered by Richard III).

1483

The disappearance of her two sons, King Edward V and Prince Richard of York, from the Tower of London. They were last seen in late summer, and Elizabeth never knew their fate with any certainty.

1484

A parliamentary decree in January declaring her nineteen-year marriage to Edward IV to be adulterous and their ten children illegitimate.

1464, 1469, 1483

Repeated accusations of witchcraft and sorcery against her mother and herself, charges that had sent earlier royal women to imprisonment and exile.

1492

Death at the age of fifty-five while living in Bermondsey Abbey with so few worldly possessions that her will mentions only ‘such small stuff and goodes that I have’ for distribution to her family and debtors.

Elizabeth Wydeville was a survivor who ultimately found her own peace in a hostile world. Her contributions to posterity are enormous. Her grandson, Henry VIII, and her great-granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth I, are among the most famous and important of English rulers. Both of these famous monarchs inherited much of their spirit, intelligence and gutsy fortitude from the first English Queen to bear the name ‘Elizabeth’. She was also the ancestor of Mary, Queen of Scots and of Lady Jane Grey. In fact, Elizabeth Wydeville’s blood runs in the veins of every subsequent English monarch, even until today.

Elizabeth Wydeville’s story deserves a fresh look and a reconsideration of the facts that have fallen into the cracks of history. Perhaps, after all, truth can be the daughter of time.

CHAPTER TWO

Edward’s Decision to Marry Lady Elizabeth

No one knows exactly when Elizabeth and Edward IV first met. The encounter in Whittlewood Forest near Grafton manor, described by Edward Hall in his Chronicle of 1548, is dated ‘during the time that the Earl of Warwick was in France concluding a marriage for King Edward’:

The King being on hunt in the forest of Wychwood beside Stony Stratford, came for his recreation to the manor of Grafton, where the Duchess of Bedford sojourned, then wife to Sir Richard Wydeville, Lord Rivers, on whom then was attending a daughter of hers, called Dame Elizabeth Grey, widow of Sir John Grey, Knight, slain at the last battle of St. Albans, by the power of King Edward. This widow having a suit to the King, either to be restored by him to some thing taken from her, or requiring him of pity, to have some augmentation to her living, found such grace in the King’s eyes that he not only favoured her suit, but much more fantasied her person…1

Agnes Strickland’s Lives of the Queens of England placed their meeting under an oak tree:

Elizabeth waylaid Edward IV in the forest of Whittlebury, a royal chase, when he was hunting in the neighbourhood of her mother’s dower-castle at Grafton. There she waited for him under a noble tree still known in the local traditions of Northamptonshire by the name of the Queen’s Oak. Under the shelter of its branches the fair widow addressed the young monarch, holding her fatherless boys by the hands, and when Edward paused to listen to her, she threw herself at his feet and pleaded earnestly for the restoration of Bradgate, the inheritance of her children. Her downcast looks and mournful beauty not only gained her suit, but the heart of the conqueror.

The Queen’s Oak, which was the scene of more than one interview between the beautiful Elizabeth and the enamoured Edward, stands in the direct track of communication between Grafton Castle and Whittlebury forest.2

Despite several errors in Strickland’s account (Grafton was not Jacquetta’s dower-castle, but the ancestral home of the Wydevilles), the meeting beneath the oak tree rings true. The legend still lives today. A public footpath between Potterspury and Grafton Regis leads to the charred ruins of an oak tree on a farm whose gatepost sign proudly reads ‘Queen’s Oak Farm’. Sue Blake, an historian who lives in the village of Grafton Regis, dismisses the claim that the tree stump remaining after five centuries and innumerable lightning strikes is the same tree that stood tall in 1461, but she finds the meeting of the couple under a tree in the royal forest to be quite credible. Oral history sometimes preserves details lost in the written documents.

But surely, this meeting would not have been the first between Elizabeth and Edward. The prominence of the Wydevilles in Henry VI’s court and the long association of Sir Richard Wydeville with the Duke of York during the French campaigns would have assured that their children met much earlier. The families of Lancaster and York, after all, were on the same side until 1455, attending the same court functions and spending time together in France. Even after the first battle of St Albans, the Duke of York remained superficially loyal to Henry until his 1459 rebellion at Ludford Bridge. The encounter by the oak tree must have renewed a long-standing acquaintance.

The written records provide tantalising facts. At the battle of Towton on 29 March 1461, Richard Wydeville, Lord Rivers led a Lancastrian force of 6,000–7,000 Welshmen who drove Edward’s troops back about eleven miles. Elizabeth’s brother Anthony, Lord Scales, was another Lancastrian leader prominent enough to be listed incorrectly among the dead by William Paston3 and in five separate dispatches sent to continental courts, including one to Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan.4 Despite their efforts at Towton, the Lancastrians suffered a disastrous defeat, after which Lord Rivers accompanied King Henry, Queen Margaret and Prince Edward in retreat to Newcastle.5

Edward IV immediately began confiscating Lancastrian property. As prominent supporters of Henry VI, both Rivers and Scales were high on his list. On 14 May 1461, a commission was issued to ‘Robert Ingleton, escheator in the counties of Northampton and Rutland, to take into the king’s hand all the possessions late of… Richard Wydevyll, knight’, one of twenty individuals whose property was seized.6

Edward IV may well have remembered an earlier encounter with the Wydevilles. In January 1460, Lord Rivers and his eldest son, Anthony, were at Sandwich organising Lancastrian troops and ships to attack Calais, then under control of Warwick’s Yorkist faction. In a surprise raid, Warwick’s troops, led by Sir John Dynham, sailed from Calais and attacked Sandwich between 4 a.m and 5 a.m.7 Fabyan’s Chronicle reports:

[Dynham] took the Lord Rivers in his bed and won the town, and took the Lord Scales, son unto the said Lord Rivers with other rich preys, and after took of the King’s navy what ships them liked and after returned unto Calais.8

Gregory’s Chronicle adds that Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, was captured with her husband.9 The prisoners were transported to Calais and turned over to the three rebel leaders: Warwick, Lord Salisbury (Warwick’s father), and the seventeen-year-old Edward, Earl of March.

William Paston’s letter of 28 January 1460 describes how Warwick, Salisbury and March taunted the Wydevilles for their low-class origins:

My lord Rivers was brought to Calais and before the lords with eight score torches. And there my Lord of Salisbury reheted [scolded] him, calling him knave’s son, that he should be so rude to call him [Salisbury] and these other lords traitors, for they shall be found the king’s true liegemen when he [Rivers] should be found a traitor.

And my Lord of Warwick reheted him and said that his father was but a squire and brought up with King Henry the Fifth, and sithen himself made by marriage, and also made lord, and that it was not his part to have such language of lords being of the king’s blood.

And my Lord of March reheted him in like wise. And Sir Anthony was reheted for his language of all three lords in like wise.10

These ad hominem slurs by political bullies may mark the beginning of the slander that has so discredited the Wydeville name. Ironically, Paston’s letter failed to note that the titles of both Warwick and Salisbury were also gained by right of their wives, a point John Rous took care to emphasize in The Rous Roll: ‘Dame Anne Beauchamp, a noble lady of the blood Royal… by true inheritance Countess of Warwick, which good lady had in her days great tribulation for her lord’s sake, Sir Richard Neville,… by her title Earl of Warwick…’.11

If Salisbury and Warwick proudly traced their royal blood back to John of Gaunt, they conveniently overlooked the fact that their maternal ancestor Katherine Swynford had been the family governess who bore Gaunt’s children illegitimately before the Duke was free to marry their mother, and that the Beaufort family name came from Gaunt’s minor castle in Champagne. Further, the men of the Neville family had traditionally gained their titles through marriages to better-endowed heiresses. This would not be the last time, however, that the pot would call the kettle black.

Neither did Paston note that the language for which his detractors scolded Anthony reflected an erudition that put those of ‘the king’s blood’ to shame. Anthony – whose translation of The Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres would become the first book published in England by Caxton – possessed an eloquence that even at this early age was apparently resented by his tormentors. His eloquence angered these men of ‘the king’s blood’, whose slurs stuck and were repeated by enemies and historians alike until a bully’s slander turned into ‘truth’ for those who knew only part of the story.

No surprise, then, that Wydeville property was confiscated by a victorious Edward IV. A letter to Francesco Sforza, dated 31 July 1461, reports the imprisonment of both men:

I have no news from here except that the Earl of Warwick has taken Monsig. de Ruvera [Rivers] and his son [Anthony] and sent them to the king who had them imprisoned in the Tower. Thus they say that every day favours the Earl of Warwick, who seems to me to be everything in this kingdom, and as if anything lacked, he has made a brother of his, the Archbishop, Lord Chancellor of England.12

This news was old, however, since a Writ of Privy Seal on 12 June had already pardoned Lord Rivers of all offences and trespasses, an order recorded in the Patent Rolls on 12 July 1461: ‘General pardon to Richard Wydevill, knight, of Ryvers of all offences committed by him, and grant that he may hold and enjoy his possessions and offices.’13 On 23 July 1461, the King ordered ‘The like to Antony Wydeville, knight, of Scales.’14

The timing is interesting. Six weeks after Towton, the King confiscated Wydeville property, but less than a month later he pardoned Lord Rivers and within two months restored all his property. On 10 December 1461, Edward IV confirmed that Jacquetta would continue to receive her dowry, granting ‘to Richard Wydewyll, lord Ryvers, and Jaquetta, duchess of Bedford, his wife, for the life of the latter of the dower assigned to her on the death of John, late duke of Bedford, her husband’. The list enumerates almost 200 properties, providing to the Duchess ‘a third part’ of their profits or a designated rent. The grant also restores to Lord Rivers the land and buildings in Calais ‘granted to Richard his father and Joan, wife of the latter, both deceased, by letters patent dated 22 April, 9 Henry VI, for a term of 90 years’. The southern boundary of the property, ‘a little lane on the side of the prince’s lodging’, indicates that Wydeville contiguity to the court was geographical as well as political and personal.15

On 12 December 1461, a ‘Grant for life to Richard Wydevill, lord of Ryvers’ restored him to

the office of chief rider of the King’s forest of Saucy, in the county of Northampton, with all trees and profits, viz. dry trees, dead trees, trees blown down, old hedges or coppice-hedges, boughs fallen without date, chattels, waifs, strays, pannage of swine, ‘derefall wode’, ‘draenes’, brushwood and brambles, perquisites of courts, swainmote and other issues within the forest, from the time when he had the same by letters patent of Henry VI.16

Although Edward IV pardoned some Lancastrians as he unified the nobility and won over his enemies, the pardons and restoration of property to Lord Rivers and the Duchess of Bedford seem extraordinary, especially in the context of their personal history (see Timeline p.274).

What could have happened to change Edward’s mind about the Wydevilles? By July 1461, the chiding at Calais and the fighting at Towton had been forgiven by both sides. The Yorkist King had pardoned Rivers and Scales for a lifetime of Lancastrian loyalty. In turn, Lord Rivers, the Duchess of Bedford and Lord Scales became solid Yorkists, an allegiance that remained unwavering until their deaths in service to Edward IV (unlike Warwick, whose allegiances shifted with the sand dunes of power). In May 1462, Anthony, Lord Scales, and his wife Elizabeth received a grant of the manor ‘called le Syche’ and other lands in South Lynn.17 By December 1462, his friendship with Edward IV was firm enough for Anthony to join the siege at Alnwick Castle near the Scottish border.

The part played by Lady Elizabeth Grey, née Wydeville, in securing the King’s pardons and restoring the family lands may not pertain at all. Or it may explain everything. All we know is that Edward departed Towton for Durham on 5 April 1461, ‘the feast of Easter accomplished’. After ‘setting all things in good order in the North’, he travelled southwards, reaching his manor of Sheen (in Richmond) on 1 June.18 The records indicate a two-day stopover at Stony Stratford, when an encounter under the oak tree may have changed history.

Not until two years later does Lady Elizabeth Grey re-enter history. On 26 May 1463, the property dispute over the land granted as part of her marriage dowry was settled in her favour.19 One year later, on 1 May 1464, King Edward IV and Lady Elizabeth exchanged vows and consummated their marriage in utmost secrecy. Thomas More claims that Edward’s courtship involved ‘many a meeting, much wooing, and many great promises’, a claim corroborated by Caspar Weinreich’s Chronicle of 1464: ‘The king fell in love with [a mere knight’s] wife when he dined with her frequently’.20 Clandestine the courtship clearly was, but its duration we do not know. The secrecy, however, indicates that Edward well understood the powerful obstacles, both political and personal, that stood in the way of marrying the woman he loved.

Perhaps the most formidable obstacle was Edward’s mother, the powerful Duchess of York. Like most mothers, Cecily Neville believed that her son could do better in choosing a wife. The young, handsome, charming King of England could take his pick of the European matrimonial market, where a plethora of princesses would bring dowries and political power to the nation. Thomas More eloquently summarises the mother’s distress, imagining her thoughts and words in the manner typical of historians of his era:

The Duchess of York, his mother, was so sore moved therewith that she dissuaded the marriage as much as she possibly might, alleging that it was his honour, profit, and surety also, to marry in a noble progeny out of his realm, whereupon depended great strength to his estate by the affinity and great possibility of increase of his possessions… And she said also that it was not princely to marry his own subject, no great occasion leading thereunto, no possessions, or other commodities…21

Edward, who clearly had learned logic at his mother’s knee (or from the flow of More’s pen) responded with idealistic conviction:

Marriage being a spiritual thing, ought rather to be made for the respect of God where his Grace inclines the parties to love together, as he trusted it was in his, than for the regard of any temporal advantage. Yet nonetheless, [it] seemed that this marriage, even worldly considered, was not unprofitable. For he reckoned the amity of no earthly nation so necessary for him, as the friendship of his own. Which he thought likely to bear him so much the more hearty favour in that he disdained not to marry with one of his own land. And yet if outward alliance were thought so requisite, he would find the means to enter thereinto much better by other of his kin, where all the parties could be contented, than to marry himself [to one] whom he should happily never love, and for the possibility of more possessions… For small pleasure taketh a man of all that ever he hath beside, if he be wived against his appetite.22

The Duchess did not retreat. She reminded her son that Warwick was negotiating a marriage with Lady Bona of Savoy, sister-in-law of Louis XI of France. To marry someone else would not only alienate the French, but would embarrass the cousin whose power and money had won the crown for Edward. But Edward had an answer for that argument:

And I am sure that my cousin of Warwick neither loves me so little to grudge at that I love, nor is so unreasonable to look that I should in choice of a wife rather be ruled by his eye than by mine own, as though I were a ward that were bound to marry by the appointment of a guardian. I would not be a king with that condition to forbear my own liberty in choice of my own marriage.23

Those words would haunt Edward’s future. Warwick, whose alienation began when Edward married Elizabeth, would indeed turn against the King, whose throne had been won with the help of Warwick’s sword. Though not immediately, they would become enemies until Warwick’s death on the battlefield at Barnet, fighting against Edward’s army.

Edward understood the larger consequences of his decision. The issue was one of control. Would he, as King, make his own decisions or must he defer to others? In resisting the Duchess of York, Edward’s enumeration of Elizabeth’s advantages over other women revealed a wit that would charm anyone but a mother:

That she is a widow and hath already children, by God’s Blessed Lady, I am a bachelor and have some too, and so each of us hath a proof that neither of us is like to be barren. And therefore, madam, I pray you be content. I trust in God she shall bring forth a young prince that shall please you.24

The Duchess was not amused. These words, too, would return to haunt Edward’s family after his death. The question of a prior commitment to marry, an oath that would invalidate any subsequent marriage, was apparently of sufficient concern for the bishops of the Church to investigate. More names the lady in question as Dame Elisabeth Lucy, but years later the Titulus Regius of Richard III would claim a prior contract with Dame Eleanor Butler. According to More:

Dame Elisabeth Lucy was sent for. And albeit that she was by the King’s mother and many other put in good comfort to affirm that she was ensured unto the King, yet when she was solemnly sworn to say the truth, she confessed that they were never ensured. Howbeit she said his Grace spoke so loving words unto her that she verily hoped he would have married her. And that if it had not been for such kind words, she would never have showed such kindness to him to let him so kindly get her with child. This examination solemnly taken, when it was clearly perceived that there was no impediment, the King with great feast and honourable solemnity married Dame Elisabeth Grey…25

If Edward’s decision was ill-advised – a questionable supposition, given the nineteen harmonious and loving years that he and Elizabeth shared – it was not made hastily. Neither was Edward naïve about the benefits of a politically advantageous marriage. For years, negotiations had been ongoing in search of an appropriate wife for the Yorkist King. In the autumn of 1461, an embassy from England had approached Philip of Burgundy about a marriage with his niece, Catherine of Bourbon. Philip rejected that match, perhaps because Henry VI and his son Edward were still alive and Burgundy was unsure that Edward IV’s throne was sufficiently secure. Mary of Gueldres, mother of King James II of Scotland, had earlier been proposed by Warwick as a possible consort, but she was much older than Edward, making the production of children uncertain. That liaison was also complicated by Scotland’s ongoing collaborations with France, and the marriage negotiations soon ended.

Isabella of Castile was offered by her half-brother, Henry the Impotent, in February 1464, an alliance rejected by Edward himself. Since Edward married Elizabeth on 1 May 1464, his reason for declining the thirteen-year-old Isabella may be obvious. Nevertheless, Isabella apparently harboured resentment about her rejection for years, telling the ambassador of Richard III that she was ‘turned in her heart from England in time past, for the unkindness the which she took against the king last deceased, whom God pardon, for his refusing of her, and taking to his wife a widow of England’.26

Against both political and maternal forces, Edward IV chose Lady Elizabeth Grey – a stunning act of independence that defied his mother, his chief military commander, and the King’s Council. That he was aware of the consternation his decision would cause is best indicated by the secrecy maintained even after the marriage. The chronicler Fabyan records the event:

In most secret manner upon the first day of May, King Edward spoused Elizabeth, late the wife of Sir John Grey, Knight… which spousals were solemnised early in the morning at a town named Grafton near unto Stony Stratford. At which marriage was no persons present, but the spouse, the spousess, the Duchess of Bedford her mother, the priest, two gentlewomen, and a young man to help the priest sing. After which spousals ended, he went to bed, and so tarried there upon, two or three hours, and after departed & rode again to Stony Stratford, and came in manner as though he had been on hunting, and there went to bed again.

And within a day or two after, he sent to Grafton to the Lord Rivers, father unto his wife, showing to him that he would come and lodge with him a certain season, where he was received with all honour, and so tarried there by the space of four days. In which season, she nightly to his bed was brought, in so secret manner that almost none but her mother was of counsel. And so this marriage was a season kept secret after, til needly it must be discovered and disclosed.27

Edward may have been secretive, but he was no fool carried away by adolescent infatuation. The King knew well that the sword of political marriage could cut both ways. Most recently, the union of Margaret of Anjou and Henry VI had produced more chaos than national advantage. If that sad situation may be blamed on the husband’s insanity and general ineptitude, other infamous royal examples revealed that marriage for financial and political gains could be personally infelicitous, most notably the unions of Henry II to Eleanor of Aquitaine and Edward II to Isabella of France.

Beyond Elizabeth herself, Edward may have been seduced by the life he witnessed at Grafton manor. The Wydevilles were a happy, loving family who cared deeply for each other, a sharp contrast to the malevolent rivalries within the family of York. While Edward’s brothers were still too young to indulge in the sibling treacheries that would ultimately annihilate the family, the King must have felt deeply the differences between the two homes. The Wydeville sons would never have slandered their mother as an adulteress – as both Clarence and Gloucester subsequently pronounced their mother – in their quests after power.

Neither had Edward’s childhood been particularly joyful. He and his brother Edmond, Earl of Rutland had been sent to Ludlow Castle at an early age for their education, and while no place was more beautiful and bustling than medieval Ludlow, Edward’s experience there was not always pleasant. ‘On Saturday in Easter week’ 1454, the twelve-year-old Edward and eleven-year-old Rutland sent a letter to their father thanking him for ‘our green gowns now late sent unto us to our great comfort’ and asking that ‘we might have some fine bonnets sent on to us by the next sure messenger, for necessity so requires’. But the letter went on to plead:

Over this, right noble lord and father, please it your highness to wit that we have charged your servant, William Smith, bearer of these, for to declare unto your noblesse certain things in our behalf, namely, concerning and touching the odious rule and demeaning of Richard Crofte and his brother. Wherefore we beseech your gracious lordship, and full noble fatherhood, to hear him in exposition of the same, and to his relation to give full faith and credence.28

The boys’ complaint about ‘odious rule and demeaning’ may represent nothing more than schoolboy whining, but Edward’s subsequent adolescent years grew progressively worse. He had just turned thirteen when his father challenged Henry VI at the first battle at St Albans on 22 May 1455. While the Duke of York negotiated a deal to serve as ‘Protector and Defender of the Realm’ during the insanity of Henry VI, he chafed at his limited power and openly rebelled in 1459. The disastrous rout of York at Ludford Bridge on 12 October 1459 caused him to flee to Ireland while Warwick, Salisbury and Edward, then seventeen, fled to Calais.

The year of 1460 saw more political skirmishes, war, and personal tragedy. The Yorkists won a battle at Northampton in July, but the year ended with their defeat on 30 December at Wakefield, the beheading of Edward’s father – his head spiked on a pole over Micklegate Bar – and the killing of his younger brother Rutland. That brother, who had shared Edward’s love for his green gown and request for a fine bonnet just six years earlier, was dead at the age of seventeen, thanks to his father’s ambition. At eighteen, Edward succeeded his father as head of the Yorkist clan.

Grafton manor offered a bucolic retreat from this brutal existence. Edward could hunt in the nearby royal preserve or saunter through the open fields surrounding Grafton village. From the London road, he could ride down either of two lanes lined with farmers’ cottages to the Wydeville manor house and the Norman church of St Mary the Virgin. Inside the peaceful, quiet country church, the tomb of Elizabeth’s ancestor Sir John Wydeville displayed a lifesize engraving of the man who had built the church tower with its five bells early in the fifteenth century.

A hermitage established in the twelfth century lay just a short distance away. The hermitage had flourished during the fourteenth century, with the Wydevilles appointing its masters. After the Black Death, however, the hermitage declined and became part of the Wydeville estate. With a cloister, chapel, dovecote and malt kiln, it was renovated during the fifteenth century. Excavations in 1964–5 discovered tiles decorated with the shields of the Wydevilles and the House of York, leading to speculations that Edward and Elizabeth were married in the hermitage. But the church of St Mary the Virgin, just steps away from the manor house, also offered a close and convenient site for a wedding. In the absence of records, the site of the ceremony remains unknown.