1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

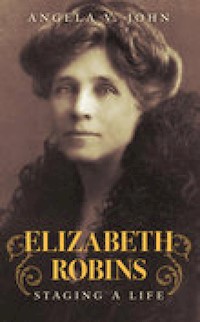

Beautiful and talented, versatile and charismatic, Elizabeth Robins was one of the foremost actresses of her day. Yet, this enduring character was also an active and lifelong feminist. This biography examines Elizabeth's historical identity and provides a study of the social culture surrounding a woman who lived a life in the spotlight.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Ähnliche

ELIZABETHROBINS

STAGING A LIFE

ELIZABETHROBINS

STAGING A LIFE

ANGELA V. JOHN

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Angela V. John is a historian and biographer. She was, for many years, Professor of History at the University of Greenwich and now lives in Pembrokeshire. Her other books include a biography (with Revel Guest) of the translator, businesswoman and collector, Lady Charlotte Guest and a life of the war correspondent Henry W. Nevinson. She is currently working on a biography of Nevinson’s second wife, the writer and suffragette Evelyn Sharp.

Cover Illustration: Elizabeth Robins as Britain’s first Hilda Wangel in The Master Builder (1893) (The Fales Library, New York University)

First published 1995.

This edition first published 2007.

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Angela V.John, 1995, 2007, 2013

The right of Angela V.John to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7524 9646 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PART I BESSIE ROBINS

1Whither & How?

2The Open Question

PART II LISAOFTHE BLUE EYES

3Ibsen & The Actress

4Theatre and Friendship

PART III C.E. RAIMONDAND I

5Come and Find Me

6The Magnetic North

PART IV ELIZABETH ROBINS

7The Convert

8Where Are You Going to … ?

PART V FROM E.R. TO ANONYMOUS

9Ancilla’s Share

10Time is Whispering

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Notes

For she had a great variety of selves to call upon, far more than we have been able to find room for, since a biography is considered complete if it merely accounts for six or seven selves, whereas a person may well have as many thousand.

(From Virginia Woolf, Orlando, A Biography, London, Hogarth Press, 1928)

To posterity the biography is indeed the life.

(Elizabeth Robins: Ancilla’s Share, London, Hutchinson, 1924)

FOR LLOYD who had the idea …

FIGURES

William Archer writes to Elizabeth in the 1890s

Map of Alaska and Yukon

Robins-Crow family tree

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book was largely conceived, researched and written in southeast London, New York City and west Wales. I owe a great debt to friends and colleagues and students who helped sustain me through discussing ideas, whether in the University of Greenwich, the Violet Caffè, Washington Square or in the less frenetic atmosphere of Upper St Mary Street, Newport, Pembs. I must, however, single out one person without whom my inchoate plans could not have been transformed into book form: Mabel Smith, trustee of Backsettown. I thank her for her faith in me, for her generosity in sharing her knowledge of Elizabeth and Octavia and for becoming a firm friend.

My fond memories of my sabbatical and summer vacations in New York are largely shaped by the reception I received at the Fales Library in the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library of New York University where the Elizabeth Robins Papers are housed. Frank Walker who was the librarian could not have been more supportive. I thank him and Sherlyn Abdoo, Alan Mark and, most recently, Maxime La Fantasie for their generous assistance. I am also immensely grateful to the Pioneer and Historical Society of Muskingum County, Ohio and to Gary Felumlee and Wendell Litt in particular. Amongst the many helpful archivists and librarians I must mention Lesley Gordon in Special Collections, the Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Her knowledge of the Gertrude Bell and C.P. Trevelyan Papers has aided me considerably. Thanks also to the staff at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin for their help and to the librarians at the Berg Collection, New York Public Library where I spent many sweltering Saturdays. I am also grateful to staff at the following: Boston Public Library; BBC Written Archives, Caversham; British Library (Reading Room, Manuscripts, Colindale and India Office Library); Churchill Archives Centre, University of Cambridge; University of Greenwich Library; The Fawcett Library, London Guildhall University; the Institute of Historical Research, University of London; Museet Lysøen, Norway; Museum of London; Department of Special Collections, University of Florida Libraries, Gainesville; Manchester Central Library, Local Studies Unit; National Council of Women, National Library of Wales; Newcastle Public Library (Reference Department); Manuscripts Section, University of Sussex Library; Tamiment Institute Library, New York University; Theatre Museum, Covent Garden; Special Collections UCLA Library and Woolwich Public Library (Reference Department).

I must record my especial gratitude to: Lisa von Borowsky for her memories and an unforgettable day at Chinsegut; Ted Dreier for his valuable recollections; Peter Whitebrook, author of a fine biography of William Archer, for his illuminating conversations and correspondence; Joanne Gates, author of a forthcoming biography of Elizabeth, who generously shared her knowledge with me; Jane Marcus who began researching the subject before I even knew who Elizabeth Robins was and gave me a much appreciated welcome in Texas; Neil Salzman, author of the authoritative biography of Raymond Robins who enlivened brunch with his ideas; Liz Staff, intrepid travelling companion in Florida; Jane Lewis for the Backsettown experience; Sue Thomas for her bibliographical expertise; Margrethe Aaby of the Press Office, Ibsen Festival 1992, Oslo for her help; Kali Israel for stimulating discussions about writing biography and Kirsten Wang for sharing her understanding of Florence Bell. Thanks also to May Morey, Lady Plowden, Patricia Jennings, Susannah Richmond, Olea Karland, Geoffrey Trevelyan and Mrs Vester for their recollections.

The other individuals who have helped me are too numerous to cite here but the following must be mentioned: Diane Atkinson, Ron Ayres, Jo Baylen, Joanne Cayford, Elizabeth Crawford, Elin Diamond, Joy Dixon, David Doughan, Iris Dove, Imogen Forster, Carmen Russell Hurff, Philippa Levine, Gail Malmgreen, Bentley Mathias, Eddie Money, Kerry Powell, Peter Searby, Harold Smith, Marcus Staff, Anne Summers, Claire Tylee, Linda Walker, Judith Zinsser.

I am grateful to the following for permission to reproduce material: The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations; The British Library; the Master and Fellows of Churchill College, Cambridge; The Fales Library, New York University; The Fawcett Library, London Guildhall University; Department of Special Collections University of Florida Libraries, Gainesville; Alexander R. James for the Estate of Henry James; Manchester Central Library, Local Studies Unit; Middlesbrough Public Library; Museet Lysøen, Norway; Richard Pankhurst; Lady Plowden; Special Collections, The Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne; Mabel Smith for the Backsettown Trust; The Society of Authors as the literary representative of the Estate of John Masefield and of the Bernard Shaw Estate for quotations from the works of Bernard Shaw; Manuscripts Section, University of Sussex Library; The Trevelyan Family Trustees; A.P. Watt on behalf of the Literary Executors of the Estate of H.G. Wells. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders.

Thanks also to the individuals and institutions where I tried out my ideas in lectures, seminars and conferences: the University of Greenwich, the Universities of Birmingham, East Anglia and Wolverhampton, the Women’s History Network, Friends of the Fawcett Library, Museum of London, Swedish Council for Research in the Humanities, Pioneer and Historical Society of Muskingum County, Ohio and Ohio State University.

My research was facilitated by grants from the Twenty Seven Foundation and the Nuffield Foundation to which I am extremely grateful. I much appreciate the support I have received from the University of Greenwich. I was delighted to have Claire L’Enfant as my editor at Routledge and I thank her, Sue Bilton, Jenny Overton, Heather McCallum, Catherine Turnbull, and also Cecilia Cancellaro in New York, for their support. Finally, a big thank you to those who read and commented on all or parts of the manuscript, Paul Stigant, Lloyd Trott and Mabel Smith. I am especially grateful to Norma Clarke for her wise comments.

Angela V. John,

December 1993

Note:

The Backsettown Trustee, the Hon. Mrs Mabel Smith, died in 2000. Copyright queries concerning Elizabeth Robin’s work should now be directed to the charity IndependentAge (formerly Rukba).

INTRODUCTION

One fine November afternoon in 1960, about forty people gathered in the garden of Backsettown, a pretty, fifteenth-century house in the Sussex village of Henfield. They had come to witness the unveiling of a blue plaque which declared that ‘Elizabeth Robins 1862–1952 Actress-Writer lived here’.1 The ceremony was performed by Dame Sybil Thorndike who talked of that ‘selfless, bright-eyed actress who was a pioneer of Ibsen in this country, a fine novelist, a good playwright, a powerful supporter of women’s suffrage, a sociologist, a humanitarian generally’. The distinguished group included the eighty-nine-year-old Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Labour politician and erstwhile advocate of women’s suffrage. He recalled first meeting Elizabeth Robins more than half a century earlier when she explained to him the nice distinction between suffragist and suffragette.

In 1993 Elizabeth Robins appeared in a ‘Missing Persons’ supplement to the Dictionary of National Biography, that other British measure of the successful public life.2 Yet she has not, on the whole, been well remembered and at the time of her death in Brighton in 1952, aged eighty-nine, she was fast becoming forgotten. Nationality and fashion can help explain her oblivion and subsequent resurgence. Kentucky-born and always retaining her American nationality, Elizabeth actually spent over two-thirds of her long life in England. Although her family was American and she had begun her acting career in the United States, set some of her novels there, returned many times, part-owned a home in Florida and helped promote international feminist connections (her sister-in-law was president of the American Women’s Trade Union League), in American eyes Elizabeth became primarily identified with Britain. Her American background gave her perspectives and even freedoms denied to her British counterparts. Yet it also meant that she could not be claimed as a British actress or writer.

She became renowned for her acting in Ibsen’s plays yet chose to retire from the stage at the age of forty, soon after the turn of the century. It is not therefore surprising that, although known to students of drama, she has not become a household name. The revival of feminism in recent years has, however, rescued her in the form of Elizabeth Robins, suffrage novelist. Although her obituary in The Times dismissed her 1907 novel The Convert as ‘frankly propagandist’,3 it was republished in both Britain and the States in the 1980s and is now viewed as a significant contribution to the literature of women’s suffrage whilst her play Votes For Women! (on which the novel was based) is acknowledged as inaugurating suffrage drama. Over the past decade the Backsettown Trust has received over two dozen requests to publish or perform her work, ranging from reprinting a short story to stage performances of her suffrage play and a musical based on The Convert.4 The programmes of recent British productions of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler and The Master Builder have devoted print and photographs to Elizabeth who was the first to play Hedda in English and introduced Britain to Hilda in The Master Builder. She has been the subject of several American doctoral theses by literary and drama scholars, one of which has been published in book form.5 A bibliographical survey has been made of her voluminous publications.6 She wrote fourteen novels, two volumes of short stories, two memoirs (one about her brother), a children’s recipe book-cum-adventure story, several booklets, two hefty works on feminism, a volume of correspondence with Henry James and many newspaper and journal articles. Two of her novels were turned into films. There is also a vast amount of unpublished work.

What other traces remain of Elizabeth Robins? How was she seen by those who knew her? And how do we—and should we—attempt to square the competing representations of her? There is the spirited young girl living with her beloved grandmother in Zanesville, Ohio in the 1870s. Her schoolfriend Nellie Buckingham declared that Bessie Robins was full of pranks and once put a Sunday School book down the privy.7 Bessie became an actress. The Bessie in Boston became transmogrified into Lisa in London, scarred by a personal tragedy which brought with it ‘self reproach which I have carried through the whole of life’. She made her home in London from 1888. Through her close friend Florence Bell (Lady Bell), we can glimpse her in high-heels, pink velvet jacket and white boa and gain some impression of her mercurial vitality and determination. Florence once wrote, ‘The passage of Elizabeth Robins through the world, a flaming torch in her hand may well bewilder those whose path in life is the beaten track’.8 A journalist presented another version of the late Victorian actress:

The glow from a pink lamp fell on her loose, clinging white cashmere dressing gown with its edging of dark fur, and flushed her face … dreaming eyes, well marked deliberately arched eyebrows, broad forehead, masses of brown hair.9

She was especially proud of that long, chestnut hair but time and again it was her eyes which would command attention. In a BBC broadcast profiling Elizabeth just after her death, Sybil Thorndike declared:

I will never forget the effect of her eyes. I think, except for Duse, I have never seen such eyes. There did actually seem to be a light behind them that could pierce through outward and visible things and see the invisible.10

One of Florence Bell’s grandchildren has recalled meeting Lisa at the railway station where her eyes could be seen ‘blazing down the platform’.11

In contrast Max Beerbohm found the actress of the 1890s a formidable prospect. He attended a luncheon held by the editor of The Yellow Book at which Aubrey Beardsley and Elizabeth were present:

Altogether a rather pleasing meal—save for the Robins … Conceive! Straight pencilled eyebrows, a mouth that has seen the stress of life … She is fearfully Ibsenish and talks of souls that are involved in a nerve turmoil and are seeking a common platform. This is literally what she said. Her very words. I kept peeping under the table to see if she really wore a skirt.12

At the same time as acting, Elizabeth was writing fiction which she initially published under the pseudonym of C. E. Raimond. She decided to assume her own name at the end of the century after press revelation of her identity. She withdrew from the stage at about the same time. This move and the dropped pseudonym may be linked to a new search for identity and identification through a confrontation with her brother Raymond with whom she had retained a romanticised symbiotic relationship forged from their fractured childhood. In 1900 Elizabeth and Raymond met in the suitably dramatic setting of Alaska. He had travelled there in search of gold but instead found God. From her Alaska encounter came the novel for which Elizabeth was most acclaimed in her lifetime and for which she was compared to Defoe, The Magnetic North.

During the Edwardian period Elizabeth became a committed suffragette, a public persona who nonetheless shunned personal publicity whilst she sought it for the cause. Understanding that she needed to tackle the prevailing conceptions of gender now focused on the struggle for the vote, she took on the establishment both from without and from within, becoming an apologist for militancy in the daily press. She sat on the committee of Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) but, whenever possible, retreated to her newly acquired Sussex home. The image she presented to local people was a far cry from Max Beerbohm’s ‘New Woman’ and those who lampooned the suffragettes. May Morey who also attended the unveiling of the plaque was the daughter of Henfield’s bicycle manufacturer whose shop was in the High Street. Elizabeth was a frequent caller and little May Powell, as she was then, adored the Miss Robins who made clothes for her doll. She recalls her as a kind of benevolent aunt, much respected in the village.13 Nevertheless Elizabeth’s personal life remained secretive, her friends unaware of her love affair in the 1890s with the Ibsen translator William Archer or her more recent intimate friendship with John Masefield.

Paul Fussell has observed that during the First World War period British society was especially rich in its appreciation of literature. To the faith in classical and English literature was added the appeal generated by popular education and self-improvement, aristocratic meeting democratic forces and establishing ‘an atmosphere of public respect for literature unique in modern times’.14 Bolstered by a larger literate public than previously but escaping serious challenge by the screen, the written medium still managed to be the message. For Elizabeth, who could also draw on an American readership and particularly appealed to women readers, the years after 1905 saw her at the height of her success as a novelist. In 1907, after the publicity of her suffrage play on the London stage, she received the extremely handsome advance of £1,000 for The Convert (someone with an annual income of £1,000 in 1907 would need to earn over £160,000 today). Even the newly famous Arnold Bennett could only command advances of £300–400 from the same publisher.

During these years Elizabeth met Octavia Wilberforce who was to be her companion for the rest of her life. As part of a literary intelligentsia with an exotic past, outspoken and boasting an international reputation, she became quite literally a woman of letters whose correspondence to newspaper editors, almost invariably concerning some aspect of women’s rights, appeared regularly in the press.

Her later fiction lacked the force and originality of works such as The Open Question (1898) and The Convert (1907), though both Camilla (1918) and Time Is Whispering (1923) are novels with powerful messages for women. Critics of her work did, however, detect a penchant for sensationalism prompted by lucrative opportunities for serialising stories in magazines whilst her non-fiction invited the very different charge of shrillness. Elizabeth’s indictment of sex-antagonism entitled Ancilla’s Share and published anonymously in 1924 was a polemical work of non-fiction which alienated support amongst those who liked to believe that the gaining of the vote was synonymous with women’s equality. Illness, war and the dislocation caused by changing continents (she spent the Second World War in America) made her last years troubled ones. Leonard Woolf-who was also present at Backsettown in November 1960, published some of her later works. He and Virginia had known Elizabeth socially and he became a member of the Backsettown Trust which administered the convalescent home for women which Elizabeth and Octavia created in 1927. Leonard Woolf remembered both her mesmeric appeal and tenaciousness. Like others, he acknowledged that she possessed ‘in a very high degree, that inexplicable and indefinable quality, personal charm’.15

Such was her time-span and the changes she witnessed that the neat historical labels of periodisation seem inadequate. How can a woman raised in the shadow of the American Civil War, later surviving two world wars, be labelled? As a young girl her main mode of transportation was an open carriage. When old, the seasoned transatlantic traveller took to flying many thousands of miles. She was both pre- and post-Freud. She confounded expectations about women of her time(s), challenging her class and gender by being the first woman in her genteel family to earn her own living, being widowed young but having no children and not remarrying, living into her ninetieth year and straddling two continents. She crossed the Atlantic over thirty times.

How did she see herself? Her passports provide a succinct visual picture. She described her face as oval, her chin square and her height 5 feet 6 inches (1.67 m), though this would not remain so, curvature of the spine losing her 3 inches (76 mm) in height; and in her seventies her weight was reduced to under 7 stone (44.4 kg). Despite adulation of ‘Lisa of the blue eyes’, she submitted that her eyes were grey. And how did she want, or rather seek, to be remembered? She told Leonard Woolf, ‘If there has been a governing passion in my life, it has been for liberty.’ Yet, as we shall see, she always recognised the power of withholding truth, aware of her own role in shaping latterday images of her. In her unpublished memoir ‘Whither & How?’ she wrote, ‘all that I go to find is my lost self’, qualifying this with, ‘or, to be as honest as possible—I go to find such fragments as I shall be willing to declare’. She delighted in her very elusiveness and actually called one novel Come and Find Me.

All biographies are necessarily historical though some are less historically sensitive than others. In some biographies the ‘times’ are presented as a rather dull backcloth to the life of the individual which becomes elevated out of all proportion. My intention is not to reduce my subject. She must remain under the spotlight of investigation but as a historian I also seek to integrate Elizabeth into her surroundings, to explore something of the circumstances and tensions which she might have faced at a particular historical moment.

The assumptions and complacency of biography writing have recently been subjected to critical scrutiny.16 On both sides of the Atlantic feminist biographers such as Nina Auerbach, Carolyn Steedman and Rachel Brownstein have experimented with the form.17 Concern has been expressed about, for example, the authorial voice and the proprietorial biographer as active agent. Barthesian claims that biography is disguised fiction have been examined and emphasis placed on seeing the life-story as a kaleidoscope of images, reconstructing through bricolage or the process of building up an image in parts in place of a unitary whole and sequential cradle-to-grave narrative. Postmoderist insistence on ‘the impossibility of knowing and writing outside of representation’,18 guides us back to the text and refuses neat, definitive accounts of a transcendent self. It also raises questions about the multiplicity of sources/texts the historian encounters which preclude ‘close reading’ along the lines of literary critics. Justifiably, historians also express some concern about the denial of agency, about the unwritten prior shaping and censorship of texts, about sufficient recognition of the past as continually in process and respect for historical particularity and temporality. And what of the danger of so reducing an individual to a cultural construct that we lose sight of the very humanity which is what tends to attract a reader to a biographical subject in the first place?

Nevertheless, such approaches have alerted historians to the fallacy of believing that we can extract the ‘real’ Elizabeth from the many layers, self-constructions and constructions by others which have composed how we ‘read’ her. We are also encouraged to question how a biographer selects and adumbrates a chosen individual, revealing something of her or his own preoccupations.

Quite apart from her fiction, Elizabeth has left us several written versions of her life-story. From the age of thirteen she kept a diary. Although her entries for most of the 1890s no longer exist (though we do have her tiny, cryptic notebooks for this period), her diary spans more than seventy years and became a regular part of her life with entries right up to the year she died. Up until virtually the end it is a reflective and detailed source (the account of the Alaska trip alone covers over 300 pages). It was used as an aide-mémoire and exercise in revising her conceptions of self and of others. It is also carefully and knowingly shaped, demanding attention as a text in the same way as her acknowledged literary work. In the diary Elizabeth practised her style and ordered her thoughts. It became a major source for her fiction and memoirs, ‘a storehouse of ideas or sensations’. Therefore as an adult she was conscious of its potential use. She also kept one eye on a possible reader. She wrote (in 1891):

I will try to write the real happenings within and without— excusing myself to myself for lack of complete frankness by calling my silences self-reverence, a dignified reserve, a 19th century— shrinking from the nude. And yet since I take the trouble (and v’y great trouble it is) for my own future guidance let me have as little dark as I can with decency reveal. As I write I feel sure I’ll forget ‘decency’ and all self-consciousness in its narrow sense as soon as I am interested in what I’m putting down.

Can the biographer so determine the points at which calculation gives way to outpourings? It may be possible to discern such shifts, aided, for example, by subtle changes in language and style, but even though we might divine some of her less crafted comments in the course of such a vast document, we shall never really ‘know’ Elizabeth. She re-read her diaries, excising, burning and commenting on entries. Yet intention was not always matched by implementation. For example, what might have become an arcadian existence with her brother in Florida, turned out very differently and although Elizabeth intended burning the less happy aspects of one of these visits, she never actually did so.

Her diary remains both rich and problematic as a source. The correspondence between Elizabeth and John Masefield reveals an aspect of her which could never have been discerned from her diaries for the same period.19 She once boasted that she told ‘not a hundredth & I tell that little to remind myself of what I do not tell’. She freely admitted that she was ‘born romancing’, that ‘There is something in people like me, secret; something that shuns the comprehension of others’. In this she was less exceptional than she liked to think but she was perhaps more frank than many in acknowledging her trait.

Even though the diary may be far from raw material, to judge diarists from what they reveal in such private writing is open to question. In the final chapter there is some consideration of Elizabeth’s views on race and ethnicity. Her combination of somewhat progressive views and reactionary fictional stereotypes was not a straightforward matter of enlightenment over time. Yet to criticise Elizabeth from views expressed in her diary raises very different issues from holding her responsible for her published accounts not least because others may have held far more questionable views than she but never been taken to task since they did not commit their thoughts to paper or if they did, ensured that others would not read them.

Used alongside other sources, the diary can be of great value to the historian through its very fashioning, subjectivity and self-censorship, helping to explain how an individual uses such a form to construct another persona. It may also be revelatory in the way that the diarist negotiates ambivalences and confronts inconsistencies and tensions (particularly in an era when much could not be articulated in public) and may help expose over time and at the same time, competing discourses.

Elizabeth’s diary forms the basis of Both Sides of the Curtain, the memoir on which knowledge of her has, to date, largely been based. It is a highly misleading source. Written during the 1930s when she was in her seventies, it is a partial (in both senses of the word) account of a thin slice of her life, the two years after her arrival in England in the autumn of 1888, with a few backward glances. Her original plan had been to cover a dozen years on the London stage and she did write an unpublished sequel, ‘Whither & How?’, about her more illustrious career from 1891.

In Both Sides she appears to be writing her own story but actually makes the English theatre the star of the book, sublimating the self so effectively that she becomes conspicuous by her very absence, a process all the more remarkable since the acting profession has not been renowned for its modesty. There are many people mentioned ‘like figures in a stage crowd’ (her words)20 but a few individuals stand out. Ironically, they are the very people she had railed against in her diary, notably George Bernard Shaw (whose correspondence with Elizabeth forms a Preface) and the actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree. The latter is transformed into a leading man.

It is a curious memoir from a woman who had led a long and eventful life. It focuses on one of her least successful periods. Although more women were now writing autobiographies, the model remained that of the male achiever. Perhaps this partly explains the book’s tone and emphasis. Jill Conway’s study of accomplished American women of the Progressive Era born between 1855 and 1865 (the decade in which Elizabeth was born), emphasises the narrative flatness of their autobiographies.21 ‘When the early women suffragists wrote their memoirs they were overwhelmingly concerned with the movement’s achievements, occluding their personal lives.22 Elizabeth’s frustration and anger at the blocking of women’s opportunities on the late nineteenth-century stage, so evident in her diary, would have receded by the 1930s and having once been articulated, was not repeated. She was now more ready to make peace with characters like Shaw particularly since few of their generation were left. The book can be seen as a commentary on how she chose to remember the past rather than how she lived it, an adjustment of the record. Possibly Elizabeth elevated the importance of men such as Tree and Oscar Wilde in order to deflect attention from the man who, slightly later, became her ‘Significant Other’, the married William Archer (who does feature in ‘Whither & How?’).

The book’s title hints at a camouflaging, a hiding behind a curtain as much as a revelation, reminding us that only at the end is the actress expected to reveal herself to the audience. Maybe Elizabeth was strategically positioning herself in this memoir. As an elderly woman, far removed from the young actress of the late 1880s who composed her diary when she was centre stage in her own production, she could now retrospectively savour her early years in London when she was poised for success. This time contrasted neatly with her imminent stardom, indicating the heroine waiting in the wings. By becoming an actress-manageress herself; Elizabeth would show her independence of the actor-managers and hangers-on of the theatre who thought they knew best and actually hindered rather than helped her success. Even her use of Shaw’s letters is double-edged since her Preface closes with her having the final word, claiming, as she had done in the past, that Shaw did not really understand her.

Both Sides provided a neat contrast to the conventional autobiographies which dwelt on the successful moments not the interstices. Known as a writer whose non-fiction was controversial, Elizabeth did not want to provide an anodyne account of life on the stage. Moreover, some of her earlier writing such as the novel The OpenQuestion and the pamphlet Ibsen & the Actress had already revealed aspects of her life, the latter dealing with her Ibsen performances. The problem, as Jane Marcus has discerned,23 is that Elizabeth tried to be ‘too clever by half’. She may have assumed the ancillary role (evident in titles such as Raymond and I and Ancilla’s Share) but her modesty may well have been a veneer which did not always pay off. Several publishers turned down Both Sides, finding it too esoteric, detailed yet not sufficiently alert to informing the reader. In August 1940 Elizabeth protested to the American publisher Putnam’s:

the kind of writer I am has a view and a purpose which are inseparable from her work. It is, briefly, to represent a phase of life, not to hop, skip, & jump over the years picking out the exceptional incidents which other people might reflect on as you are recording.

Both Sides was published in 1940 but in wartime Britain it did not receive much attention.

However calculated her self-effacement, it is significant that Elizabeth’s book was about the London stage. Her move to London represented a rebirth after personal tragedy in America. Although she made her name in European drama, Elizabeth did not, however, became a legend like Rachel the French tragedienne, remembered in the history of European theatre as ‘the first great international dramatic star’, or like Sarah Bernhardt or Eleonora Duse whose funeral in New York produced a crowd of 3,000 outside the church (tickets were issued).24 Neither did she attain the status of a Mrs Siddons or Ellen Terry. Indeed Elizabeth Robins’s name was largely associated with the non-commercial theatre and the shock of the new.

She was indubitably shaped by her years on the stage. Acting before modern sound25 or visual techniques, the Victorian actress’s work seems especially ephemeral to us today. Yet precisely because of the lack of such alternative means of entertainment, live performance was valued. It was Elizabeth’s role as Hedda Gabler which caused the greatest stir. As the Sunday Times put it, here was ‘one of the most notable events in the history of the modern stage … it marks an epoch and clinches an influence’.26 And whether critics loved or hated Ibsen, they certainly took notice of him and those who played his characters. Elizabeth may have left the stage prematurely but the stage was not allowed to leave her. Mrs Pankhurst was attracted to the idea ofElizabeth Robins as a leading suffragette precisely because she had been an actress.

Although, as we shall see, Elizabeth disliked theatricality in others and stage-managed, produced and performed many different jobs connected with the stage, including establishing a radical new theatrical company, it is as an actress and especially as an interpreter of Ibsen on the stage (despite having a much wider repertoire) that she is remembered in the theatrical world. She became framed by her Hedda role and typecast as the Ibsenite ‘New Woman’. When the poet Richard Le Gallienne met Ibsen in Norway in the 1890s he said the great dramatist put one question to him: ‘Did I know Miss Robins?27 When Elizabeth died, one of her obituaries was headed ‘The last of the Ibsenites’.28

Elizabeth’s two careers, acting and writing, required acute observation. Her travels and her connections gave her rich material. Her address books read like Who Was Who. She dined with society figures, with leading names in the artistic and political world and international thinkers, radicals and feminists over a period of about sixty years. She learned to watch closely and she took care to compartmentalise her activities. Her catholic range of friends and interests, not always gelling well with each other, laid her open to charges of being double-faced. Her intense concern about whatever subject was currently absorbing her, invited charges of self-centredness and a suspicion that she wilfully used people for her own advantage. There was an element of truth in this. From an early age Elizabeth had had to learn to fend for herself and she understood that her determination played no small part in her success. Nevertheless, there were those, usually successful men, who were slightly unnerved by her. She disturbed their expectations and stereotypes: why did she insist to actor-managers that she knew best when they were the ones who could help her? Why did such a beautiful woman become a suffragette? From theatrical figures like Charles Wyndham to literary names such as Leonard Woolf she was something of an enigma, refusing to be typecast and inviting simultaneously both their admiration and their desire that she were less ‘vampiric’.

She seems to have been highly sensitive about how people perceived her and concerned that they should not come too close. She was well practised in the art of dissimulation and acknowledged that ‘Most if not all of us, are occasionally engaged, consciously or unconsciously in making ourselves out better or worse than we really are’. In the spring of 1895, ill and conscious of mortality, she penned a brief record ‘for the enlightenment of the people who care for me’, admitting that ‘any account of the way I have spent my life must be more misleading than true’ and acknowledging her

constitutional unwillingness to letting people know what seems to myself to be the real ‘me’. I am afraid I have moods when I delight to darken counsel on this subject. If I see any one trying to ferret me out, my greatest delight is to baffle & elude my pursuer & leave him contentedly following a false scent … I have partly deliberately & partly unconsciously ‘cooked my accounts’.

Yet the ‘cooking’ of her accounts matters less than the need she felt to do this. This biography will explore such issues through her and others’ words. There are plenty of these. In the Elizabeth Robins Papers in the Fales Library of New York University there exist nearly a hundred linear feet of her material. The Finding Aid alone exceeds a hundred pages. Numerous other sources by and about her exist elsewhere in America and Britain.

Appreciating the significance of naming, I have divided the book into five sections, each with a name by which Elizabeth was known: Bessie, Lisa, C.E. Raimond, Elizabeth Robins and the term latterly used by friends, E.R. They correspond to different stages in her life but clearly there is overlap: to childhood friends and family she was always Bessie just as she is still Lisa to the Bell descendants. These divisions however, permit both a broadly linear structure and the opportunity for examination of her major concerns and interests in a thematic form which places them in a historical context and does not isolate the individual from wider societal change.

Bearing in mind the fact that I am a woman historian writing in the late twentieth century and thereby privileged to enjoy the perspective which only time and distance from the subject can provide, yet also inevitably bound by my own period, I have placed emphasis on how I see Elizabeth Robins having staged her life. Part I focuses on her in America, considering her early influences and how she created a career on the stage. The second part shifts to London, her years in the British theatre and the friendships she made during this time. There follows an examination of Elizabeth as a writer of fiction and journalism in the 1890s and 1900s and of the significance of her Alaskan trip. Part IV evaluates her contribution to the women’s suffrage movement, discussing not only her fiction but also her lesser-known writings on militancy and her shifting commitments. In addition it considers her exposition of the white slave trade and the origins of this work through her connections with John Masefield. The final part discusses her deep friendship with Dr Octavia Wilberforce and their efforts to improve women’s health. It considers Elizabeth’s feminism during and after the First World War, her opposition to militarism and her contribution to Time and Tide. We see her return to America, her concern about race, difficulties with Raymond and final troubled years. Each chapter is named after one of her works.

Elizabeth may have gained a plaque and she is now be celebrated at her childhood home in Ohio but we cannot unveil the quintessential self, what she called ‘the real “me”’.29 Yet we can examine through her words and those of her contemporaries how multiple, shifting identities were constructed by her and for her at particular times and in different places. Through this individual and biographical history, perhaps we can also begin to understand somewhat better some of the demands and concerns of, for example, the theatre, literature and the women’s movement in the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries.

PART I

BESSIE ROBINS

1

WHITHER & HOW?

On 6 August 1862 during the American Civil War and in the middle of a wild storm, Elizabeth Robins was born. Her parents, Hannah Maria Robins (née Crow) and Charles Ephraim Robins, were first cousins living on East Walnut Street, Louisville, Kentucky.1 Elizabeth, known as Bessie, was their first child though Charles had a son from a previous marriage. In later years Elizabeth would refer proudly to her Kentuckian heritage though she actually spent little time living there.

The family moved to St Louis for some months when she was under a year and although they returned to Louisville briefly, they went east before she was three. Her father, fascinated by science and the social sciences, tried to convince himself that he was a businessman. He worked in insurance (his own father had been a pioneer in the development of life and fire insurance) and as a bank cashier. His bank somehow survived the panic of 1857 but a few years later a recently formed banking partnership (Hughes and Robins) collapsed. So before the end of the Civil War the family moved to New York in search of better times. Charles was employed by the Home Insurance Company on Broadway and they lived on the south shore of Staten Island, just outside Eltingville. Here he cultivated the soil and conducted chemistry experiments in the barn. He spent much of his time planning for the future though few of his dreams were realised. Foundations were laid for a big house but typically it never got built, the family residing instead in the lodge on their Bayside land.

There is not much evidence about Hannah in this period. Refined, of gentry stock and musical—Elizabeth later recalled her singing haunting airs and one particular aria from Il Trovatore—she was in her mid-twenties when she moved to Staten Island. For much of the next decade she was pregnant. A son, Edward, born in Louisville two years after Elizabeth, did not survive. Hannah then had five more children in the next eight years. Eunice, known as Una, was Elizabeth’s only surviving sister since baby Amy also died in infancy. The eldest boy was Saxton, seven years younger than Elizabeth. In 1872, the year that Vernon was born, Charles was devastated by the death of Eugene, his adolescent son from his first marriage. Eugene had studied at a military academy. It was, however, the birth of the youngest and ultimately most successful son in the following year which ironically presaged the greatest tragedy for the Robins family. Raymond’s birth resulted in severe post-natal depression for Hannah and thereafter a perilous mental state. There was also financial disaster: her fortune was lost on Wall Street. The marriage floundered.

The young Elizabeth’s life now changed dramatically. In August 1872 the family moved to her paternal grandmother’s home in far-off Zanesville, Ohio. Her beloved papa left for a metallurgy course in St Louis then headed west for a mining life in Colorado. Her ailing mother was soon placed under the watchful eye of her brother-in-law Dr James Morrison Bodine, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Louisville. Saxton joined his mother in Louisville. Vernon and the baby of the family, Raymond, who was always Elizabeth’s favourite, remained with their sisters in Ohio for the time being though eventually the boys also left for Kentucky.

Not surprisingly given the upheavals of her childhood, at the age of ten Elizabeth saw herself as already ‘disagreeably old in observation and experience’. Yet her new life actually gave her a stability she had long been denied. This was largely because of her remarkable grandmother, Jane Hussey Robins, who now became the central figure in her life. Long widowed and in her seventies she appeared undaunted at the prospect of once more raising a young family. She earned Elizabeth’s lifelong respect and love. Elizabeth dedicated her most personal novel The Open Question (1898) to this ‘most stern and upright judge’, her grandma.2 Elizabeth’s notes for this book show that it was written ‘just for her and me’, a tribute to the woman who had been her guide and mentor. Its most memorable character is Mrs Gano, a thinly disguised grandma. In fact Elizabeth’s grandfather had founded a Baptist theological seminary in Cincinnati and one of his co-founders was an Aaron Gano. Elizabeth would comb her family history for names and incidents for her stories. She found particular delight in an aunt, Sarah Elizabeth Robins (Aunt Sallie) who not only possessed her name but also wrote drama and poetry, was inspired by seeing the French tragedienne Rachel, knew Edgar Allan Poe and published stories. It was, however Grandma who was, in Elizabeth’s words, her ‘touchstone’, always far closer to her than her own mother.

Tall, with a commanding presence, she was a deeply religious and principled woman with a keen sense of loyalty, strict yet fair. At the same time she was acquainted with modern literature. In 1882 she was reading The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James, later to become one of her granddaughter’s close friends. She explained in a letter to Elizabeth that James seemed to be ignorant of woman’s nature, ‘its complex machinery, its hidden springs of motive and passion— its actual working and latent possibilities’. In contrast, George Eliot, Charlotte Bronte and George Sand wrote differently, understanding their own sex ‘and by strokes of genius, have succeeded in portraying womankind’. The Zanesville Signal felt the portrayal of Mrs Gano in The Open Question to be a little harsh3 but Elizabeth was concerned to represent her in this story as a child might perceive her.

The novel also dwelt lovingly on Elizabeth’s Ohio home, the Old Stone House. Her grandmother had moved there from Cincinnati in 1858. Charles Robins who was then working as a cashier at the Franklin bank of Zanesville also lived there with his mother and, until she left him, his first wife, Sarah.

The Old Stone House on Jefferson Street in the township of Putnam had its own distinguished history.4 In the year that Elizabeth settled there Putnam became part of Zanesville though this old township on the bank of the Muskingum river retained a sense of separate identity since it had originally been founded by New Englanders. Unlike the other local houses Elizabeth’s home was built of stone. This well-proportioned, Federal-style building had been erected in 1809 in the hope of its becoming the permanent legislative seat for the new state of Ohio. Although Zanesville on the other side of the river enjoyed this honour between 1810 and 1812, Columbus became the state capital thereafter. The Stone Academy, as Elizabeth’s home was originally called, housed a grammar school between 1811 and 1826. The women of Zanesville and Putnam Charitable Society also met there as did, for a time, the United Presbyterians. Elizabeth’s school, the Putnam Seminary for Young Ladies, originated there but soon moved to a handsome building on nearby Woodlawn Avenue. The Old Stone House’s secret passage leading from the cellar to the river may have been part of the ‘underground railroad’ network for runaway slaves and the house hosted one of the first conventions of ante-bellum Abolitionists.

Such a home helped instil in Elizabeth a love of history. This later found expression in her wanderings round London, her perusal of books on the history of Sussex and a loving account, written in England, of one of the books kept in the Old Stone House library, The British Merlin, a detailed almanack for the year 1773.

Yet the young Bessie Robins was far from being an introverted bookworm. Within a few months of arriving in Putnam she was part of a group of nine who called themselves The Busy Bees, held their own fair and wrote a song about the wares they sold.5 After a week in the Putnam Seminary (granted collegiate status in 1836), Elizabeth was writing to her mother explaining that she was studying geography, arithmetic, reading and spelling and liking school very much. Certainly her spelling had improved since an earlier letter (probably dating from about 1870) in which she had described a visit to the zoo in ‘scentrail’ Park, Manhattan and signed herself ‘Your affectionate dater’. Elizabeth remained at the Put. Fem. Sem. as it was known, for nearly seven years though by the age of sixteen her appreciation of school was less dutiful. Fresh from George Eliot’s Middlemarch, she wrote that the start of term and ‘continual chemistry, geometry etc etc is enough to cloud the sunniest temper’. Her father had already warned against time-wasting novels. He was anxious that she regained her position as the school’s best scholar. To his dismay she found science a tribulation though reading and writing provided welcome scope for her fervent imagination.

One of her compositions about a lawyer’s wife declares her occupation ‘far more necessary than that of a lawyer’. Where would the latter be without his wife’s cooking? His very words depended on her. The title of another story about the fortunes of a button includes the word ‘Herstory’ now incorporated into feminist vocabulary. It can, however, be questioned whether the twelve-year-old writer was actually ‘conscious of its feminist content’ as has recently been claimed even though Elizabeth chose her words carefully.6 Two years later, influenced by the presence of her grandmother, disillusioned by the absence of her mother and infrequent appearances of her father, she declared that if women did their duty better there would be fewer worthless men. On leaving school she studied at home, her father’s influence evident in her diet of reading which included the Boston Journal of Chemistry and the Engineering and Mining Journal (for which Charles was briefly a sub-editor).

The teenage Elizabeth was now dreaming of a life far away. In later years the Zanesville Signal (with the benefit of hindsight) recalled her as ‘excessively, almost immodestly, ambitious’.7 Since 1876 she had kept a diary. Early entries such as ‘Going to begin to be good tomorrow’ suggest her rebellious spirit. Her schoolfriends Kate Potwin and Emma and Julia Blandy feature prominently in her diary as do the boys they know. With these friends—characteristically Elizabeth was still corresponding with Emma in the 1920s—Elizabeth developed a love of the stage. She was prominent in school recitals. Her rendition of part of the closet scene in Hamlet at the age of fifteen prompted the local newspaper to comment on the ‘fire and effect’ usually attributed to ‘the sterner sex’ and after another recital to speculate whether she might have a future as a reader. The future actress later commented that Mama had once been considered the finest reader in the Shakespeare Club. Elizabeth and four Blandy girls were members of an Amateur Dramatics Club and performed a two-act comedietta Which of the Two? which she stage-managed. She also played the flirt Arabella in a short comedietta set in England entitled Who’s to Win Him? This was a substitute role in the newly opened Schultz Opera House in Zanesville. Schultz lived in a mansion opposite Elizabeth’s home.

The first professional play she saw was at Macaulay’s Theatre, Louisville where, aged fourteen, she watched Edwin Adams as Macbeth. Her early adulation of Mary Anderson was partly because the actress shared her birthplace and it was after seeing her that she wrote a ‘wild letter’ to her father about going on the stage. He was shocked. Acting in school and family theatricals was one thing: going on the stage professionally was quite another and anathema to a family which saw itself as part of the gentry despite its impoverished position. Other young women from more modest backgrounds faced opposition on choosing the stage for a living. Clara Morris’s mother, a housekeeper and seamstress, was ‘stricken with horror’.8

The position of the American actress seems to have improved slightly from the 1860s. Elizabeth’s grandmother certainly felt that there was less superstition and bigotry surrounding the theatre than there had been earlier. Nevertheless, the legacy of New England Puritanism remained strong as did any threat to the deification of the home. Constantly in the public eye and deliberately shunning anonymity, the actress enjoyed almost unparalleled freedom in a profession which anybody could enter and where it was still possible to succeed without formal qualifications. Elizabeth’s father criticised the way the press appropriated and exaggerated the personal lives of actresses. Associations with immorality lingered on. The term ‘public woman’ was used interchangeably for performer and prostitute. 9

Those outside the theatre were also often wary of people whose livelihood depended on perfecting the skills of deception. In Both Sides of the Curtain, Elizabeth tells of her father’s encounter in the mid-1880s with his actress daughter.10 On tour with James O’Neill (father of the playwright Eugene) in The Count of Monte Cristo, she played his lover Mercedes in her home town. To her profound humiliation, ‘Before all the world’ her father walked out of the Zanesville Opera House in the middle of the second act. His objection was to her assumption of distress, ‘all that in a world of real suffering—of disaster’ and he refused to watch any more of what he disparagingly called ‘play-acting life’. And Grandma was mortified to think that Elizabeth was playing an outcast (Martha in Little Emily) before the Boston public. She also objected to her playing King Lear’s daughter Goneril: ‘How can you successfully assume such a character as the undutiful, unnatural daughter of the poor distraught king?’ Hannah’s letters urged her daughter to play modest and appropriate roles: ‘Don’t accept any role that a lady or pure girl would be ashamed to own, I could almost rather see you dead than personating vile women.’ Ironically, years later a distinguished playwright who rather specialised in writing about ‘women with a past’ told Elizabeth: ‘I see your line is sympathetic outcasts.’

Before Elizabeth reached the stage, her father made one serious effort to deflect her attention. In the spring of 1880 she boldly sought out the great actor Lawrence Barrett when he came to Zanesville and asked him if a young girl could become a fine actress without dramatic training. He denied that training could ever make a great actress. It was necessary to start at the bottom and by careful observation and practice work up to the top. She wrote to tell her father that as soon as Grandma no longer needed her she must carry out her plan to act. Aware that she might run away rather than be consigned to a life at home with her uninspiring sister, Charles now dangled before his daughter the prospect of a summer in a camp at the highest gold-mines in the world up in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. He had once more changed jobs and was now employed by the Little Annie Mining Company as the financial agent at the Summit camp, Rio Grande, 11,300 feet (3,444 m) above sea level. It was a somewhat extreme move taking an adolescent daughter to live in a mountain mining camp but so, in her father’s view, was a future on the stage.

Early in June 1880 the Juan Prospector reported the arrival of ‘Professor Robins and his accomplished daughter Miss Bessie’ (Charles had taken a metallurgy course at the University of St Louis so was known to the miners as the Professor or the Doctor). During the ensuing months Elizabeth and her father were at their closest. Here he could expound his scientific and political theories, show his daughter the mines and mills, teach her to assay and operate the weather signal service, and generally shape her reading and thinking. For a father who maintained that ‘The only knowledge worth having is knowledge of nature’ she was in the right place. She enjoyed freedoms unheard of at home, travelling like Isabella Bird before her in a Mountain Costume complete with alpine stock (long before she created the role of Hilda Wangel). On 4 July the future actress read out the Declaration of Independence above the timberline to an appreciative audience. She went snow-shoeing (skiing), climbing and riding, collected wild flowers and specimens of ore for her cabinet. On her eighteenth birthday she made an assay of the San Juan tailings, her father presented her with $1,000 of Little Annie stock and the men made her a gold ring.

There are several sources for the fourteen-week adventure in a mountain camp including Elizabeth’s own diary and the letters she wrote to her grandmother. In the late 1920s she reworked much of this material into a sprawling story of over 600 pages, initially called ‘Kenyon and His Daughter’; she later changed the title to ‘Rocky Mountain Journal’. It seeks to present these months from the viewpoint of her father. In addition to name changes, Grandma is conspicuous by her absence ‘which I regret to the deep of me’. This was a deliberate decision to avoid too much similarity to The Open Question though in fact ‘Rocky Mountain Journal’ never found anyone prepared to publish it. Elizabeth probed the apparent innocence of the original diaries and letters. The ‘yellow-haired’ unkempt girl had given way to an attractive and tanned young woman with long, chestnut hair. She had come to a camp full of miners who saw little of women. In the story she portrays the anxiety she presumes her father felt about her and his bewilderment at her mixture of precocity and naïveté. There is a suggestion, probably enhanced by the gap in time and the author’s later feminism, of the young woman in control of herself and deliberately choosing not to ‘tell all’, the woman’s use of silence to which she would refer so frequently in her writing. Her father is so disturbed when he finds a miner kissing her and his daughter never alluding to it, that in this fictional account he reverts to urging a suitable marriage as the solution.

The story underscores the hopelessness of her father’s own marriages and here and in another story, ‘The Pleiades’, there is a suggestion of his involvement with other women. Some of this—for example, his wife bolting the door against him and making him homeless for five years—may simply have been for dramatic effect but it is interesting to see that the feminist Elizabeth Robins reserves the sympathy for him, presenting her (fictional) mother as unsympathetic, shallow and stiff. The heroine, named Theo (not Thea) is the daughter who replaces the son who has died, or at least seeks to fulfil this impossible task. Above all, this story is Elizabeth’s attempt to come to terms with her father.

Despite the blows life dealt him, Charles Robins liked to impress his own experiences upon his children’s minds. He reminded them how he had studied as a young man but earned his living since he was eighteen (his father had died when he was twelve). Elizabeth was told that she was descended from intellectuals on both sides of the family and, as the eldest, could not fail to mould the boys’ tastes (Una always seems to have been left out of such considerations). Charles had been influenced by the communitarian experiments of the Welshman Robert Owen and the French utopian socialist Charles Fourier. He was attracted by Auguste Comte’s positivism and by Herbert Spencer. Perhaps the two greatest influences were the American Henry George, author of Poverty and Progress, and the British evolutionist Charles Darwin. As Elizabeth observed, science became his religion. In one of his many long letters he told her that ‘The change wrought by Darwin is incomparable and universal. It will bury Theological agnosticism in the same grave with teleology–for it not only shows a way by which the Cosmos might have come to the point where we see it without God—but its demonstrations definitely excluded Him from all that we see of Nature.’