9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

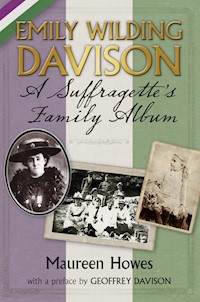

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Emily Wilding Davison's image has been frozen in time since 1913. On the 4 June of that year, Emily was struck by the king's horse, Anmer, during the Epsom Derby. She died four days later. She, unlike her fellow Militant Suffragettes, did not live to write her memoirs in a more enlightened and tolerant era. In the aftermath of the Epsom protest, her family and her northern associates were caught between two very powerful factions: the Government's spin doctors and the very efficient publicity machine of Mrs Pankhurst's W.S.P.U. In response, Emily's family and associates closed ranks around her mother, Margaret Davison, and her young cousins. For almost a century, their silence has guarded Emily's story. Now, at the centenary of Emily's death, her family have come together to share Emily's side of the story for the first time. Drawing on the Davison family archives, and filled with more than 100 rare photographs, this volume explores the true cost of women's suffrage, revolutionizing in the process our understanding of one of the defining events of the twentieth century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

I am much moved to learn that Emily Wilding Davison, a renowned name in British history and known for the self-sacrifice which helped her to win women the vote, is being remembered in her native Morpeth.

As the son of Sylvia Pankhurst I have heard her, and other veterans of that struggle, speak of Emily Wilding Davison with veneration as long as I can remember.

My warmest greetings on this historic occasion to Maureen Howes, the Davison family, Councillor Andrew Tebbutt and the people of Northumberland.

Richard Pankhurst, 2013

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to four special people who are no longer with us:

My husband Terry, whose down-to-earth common sense for forty-seven years kept me firmly grounded.

Bill Brotherton, formerly of Morpeth and latterly of Pembrokeshire, Wales, a Caisley/Woods descendant whose extensive knowledge of the family’s mining history was invaluable.

Renee Bevan of Hepscott, a Caisley/Wilkinson descendent, whose delightful, wry sense of humour made researching this book a sheer joy.

Moira Rogers of Bristol, the granddaughter of Isabella Georgina Davison, Emily Wilding Davison’s half-sister. After her marriage, Isabella lived in Killough Castle, Tipperary, Ireland. Moira shared with me her family’s amusement when the news broke that Aunt Emily had been discovered hiding in the Houses of Parliament.

And to the Davison/Caisley family members, who shared with me their grandparent’s version of the Emily Wilding Davison story.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface

The Suffragette

The Silence is Broken

Research Begins

The Early Years

The Morpeth Years

New Jobs, New Houses and the Loss of a Beloved Sister

Emily as a Child and a Young Woman

First Year as a Governess

The Layland-Barrat Years, 1904–1907

Militant Suffragette, 1906–1913

The Epsom Story Begins

Derby Day

Arresting Mrs Pankhurst

After the Accident

Remembering Emily

A Suffrage Timeline

Copyright

Acknowledgements

I WISH TO ACKNOWLEDGE the debt of thanks that I owe to so many people who have encouraged me to continue with this very special project. I am aware that without their continued support and guidance Emily Wilding Davison’s – and the women of Morpeth’s – involvement in the Epsom protest could so easily have been lost to our nation’s historical record. Together we have shared an amazing journey, and in doing so we have changed how much-loved ‘Aunt Emily’ will be perceived from now on.

My especial thanks to my sister-in-law, Cynthia Claypole of Rampton, Nottinghamshire, for her loyal commitment and her genealogical skills; to Geoffrey Davison of Sydney, Australia, for his encouragement, advice, strength and kindness; Rodney Bilton of Formby, Lancashire: saying ‘thank you’ just does not seem enough, for his family archive opened up an unexpected window into Emily the suffragette’s life; Gordon and Pat Shaw of Morpeth: thank you for trusting me with your special knowledge; Christine Telford of Morpeth and Aberdeen; Irving Rutherford of Morpeth; Robert Wood of Guidepost, Northumberland; the Bedlington/Caisley family groups, who are descended from Emily’s great-uncle, Thomas Caisley: many thanks to everyone for your families’ stories re the Caisley/Woods mining information; Professor Richard Pankhurst, who sent a message of support to the people of Morpeth and shared with me his family memories relating to Emily Wilding Davison; Dorothy Luke, Lou Angus and Sue Coulthard and their fellow members of the ninetieth anniversary tribute committee, 2002–3; to the following chairmen of the various Emily Wilding Davison committees that I have been involved with: Jim Rudd, Adrian Slassor, Mark Horton, and in more recent time, in particular Councillor Andrew Tebbutt and the committee members of each succeeding group within Castle Morpeth Borough Council, Morpeth Town Council; the Emily Wilding Davison Working Group; Morpeth’s Stobhillgate Townswomen’s Guild, whose membership had many Caisley/Davison present-day descendants whose local knowledge was the foundation of my suffrage research; Morpeth’s Soroptimists; Morpeth’s Business and Professional Women’s (BPW) Foundation; the staff of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Morpeth and Northumberland, Durham, and Tyne & Wear Library and Archive Services, all of whom at various times during the past decade have keenly supported me in this special research project; an especial thanks to staff of Northumberland Collections Archive Service at Woodhorn; to Professor Carolyn Collette and her late husband David; Nick Hide of London and the Davison Clan Association; V. Irene Cockroft of London; David Neville; Dr Joyce Kaye of Stirling University; Dr Dorothy Pollock of Canada; Mr Bruce Gorie of the Lord Lyon’s Office, Edinburgh; Mrs Bette Lindsay of Nedderton; Mr Chris Streek of the Royal Armoury, Leeds; I thank you all for the special interest and the input you have given me.

Finally, to all the present-day family members who are aware of their unique contribution: if I have inadvertently missed anyone, please accept the following family group listings to include you and your family:

Emily Wilding Davison’s northern family connections (in alphabetical order): Anderson family, Simonburn, Northumberland; Anderson/Andrucci families, Morpeth and Ashington, Northumberland; Caisley/Anderson families, Morpeth and Bedlington, Northumberland; Caisley/Bilton families, Whitley Bay, Darlington, Formby, Merseyside and Epsom; Caisley/Blackhall families, Morpeth; Caisley/Waldie families, Morpeth; Caisley/Wilkinson families, Hepscott and Morpeth; Caisley/Wood families, Morpeth and Pembrokeshire, Wales; Davison/Anderson families, Alnwick and Morpeth; Davison families, Sydney, Australia, Essex and Hampshire; Davison/Hughes family, Mooroolbark, Victoria, Australia; Davison/Rogers family, Bristol; Redpath/Wood families, Morpeth.

Preface

EMILY WILDING DAVISON:A Suffragette’s Family Album is a unique publication. With patience abounding, the careful building of trust and with integrity beyond reproach, long-time Morpeth-based genealogist Maureen Howes has brought to the surface for the first time – with the full support of the Davison and closely interrelated Caisley, Cranston, Anderson, Wood, and Bilton families and together with the peoples of Morpeth and Longhorsley – the missing story, in photographs, of Emily Wilding Davison – of her family, of her education, and of her Northumberland roots.

It disposes of the myths and misinformation created by diverse interests of the time, and fuelled by the media and highly placed Members of Parliament, surrounding an event significant in British history and in the enfranchisement of women in the United Kingdom – a right already enacted some twenty-five years beforehand in New Zealand, in 1893, and thereafter in Australia in 1903.

My great-aunt Emily Davison was indeed not a mad woman intent on pointless suicide. Nor was she an intended martyr, as frequently claimed and speculated upon by many who sadly – or conveniently – knew no better. She was a highly educated, extremely intelligent and well-connected lady, of a strong and supportive family background with a rich Northumberland heritage.

Maureen Howes has gained unrestricted access to previously tightly held records, of private family photographs, and of personal items, from which she has classically rewritten history here, with the benefit of factual evidence – not from ill-advised nor ill-informed speculation, nor from conjecture.

It is my privilege to commend this wonderful pictorially true story to all to take in, to ponder, to reflect upon, and of which to be proud.

Geoffrey Davison,

Davison Family titular head,

Sydney, Australia,

21 March 2013

The Suffragette

‘Among the calamities of war may be jointly numbered the diminution of the love of truth, by the falsehoods which interest dictates and credulity encourages.’

Samuel Johnson, 1758

MORPETH, WHERE I LIVE, is a small market town where everyone knows everyone – in the nicest possible way, of course. I was recently in a taxi passing St Mary’s churchyard, where Emily Wilding Davison was buried in 1913, when the driver said, ‘You’re the lady who’s writing a book about “that woman” who’s buried in there, aren’t you?’

‘Do you mean Emily Wilding Davison, the suffragette?’ I answered.

In a slightly exasperated voice, the driver replied, ‘But does anyone really care about any of that nowadays? It was so long ago.’

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘There are many who care about her story here in the county: her life and times are going to be celebrated here in Morpeth, and also in Epsom, on the centenary of her death, to honour her fight for equal rights. When Emily came to live in Northumberland with her mother in 1893,’ I told him, ‘after her father had died, she had over forty first cousins in the area – and I’m still counting! Many of their descendants from around the world will be coming to help us celebrate in June of this year.’

The driver looked at me and said, ‘You’ve counted her cousins!’

I laughed, and I explained that that was how I had become involved in the first place: after retiring as a genealogist ten years ago, I was asked to volunteer my services in order to find her present-day relatives. The plan was to record their stories before they were lost forever.

Later that day, recalling the conversation, I realised that his opinion was also shared by many others. After researching Emily’s life and times, I have come to believe that her story is just as relevant to us today as it was in 1913. However, I am the first to admit that Emily Wilding Davison has an ‘image problem’. In all honesty, I admit that there was even a time when I myself shared the same view as my taxi driver (and, perhaps, as many of today’s general public). After reading the above heading, you may have involuntarily exclaimed, ‘Oh no! Not another version of how that woman chose to kill herself!’ Or perhaps, ‘There cannot possibly be anything new to add to her story!’

Epsom racecourse in the early Edwardian era. (George Grantham Bain Collection at the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ggbain-08238)

Those long-held assumptions reflect the worldwide perception of Emily Wilding Davison. They are also the reason why anyone who has dared to question the accuracy of them has sometimes been the target of similarly hackneyed responses. However, none of these assumptions about Emily are true. Samuel Johnson’s famous observation (quoted on page 11), aimed at the fledgling newspapers of 1758, reflects that truth itself is the first casualty of war. This phrase aptly reflects the national headlines in 1913 after our suffragette’s final protest at Epsom. How and why did truth and Miss Davison become acceptable casualties in the long and bitter fight for the women of Britain to obtain the right to vote? Whose interests were being served in the media following the death of Emily Wilding Davison, who was the fourth suffragette to be killed in Mrs Pankhurst’s war of attrition against an increasingly intransigent government? I consider that this project is a work-in-progress, and I hope that others will be inspired to take up the cause after I, and my generation, are long gone, and to find the truth that lies behind every suffragette’s story.

This work is a record of a remarkable family history research project, which, as it progressed, became in every sense a modern-day detective story. It revealed the closely knit ties that Emily Wilding Davison had to her wide circle of family members in Northumberland, and uncovered previously unrecorded family stories, allowing the reader to get closer to the events surrounding the suffrage movement and the protest that was carried out by Emily Wilding Davison at the Epsom Derby of June 1913, an event which ended so tragically. From this new and original material we have an opportunity to form our own conclusions, conclusions which may question the long-held views regarding Miss Emily Wilding Davison – views which have never been seriously challenged before.

The Silence is Broken

ON 4 JUNE 1913, suffragette Emily Wilding Davison was struck and fatally wounded by the King’s horse, Anmer, after she ran onto the racecourse at Epsom Downs, Surrey, during that year’s Epsom Derby. Pathé News had a camera running that day, and seeing the flickering black and white images they captured, showing Emily Wilding Davison stepping onto the racecourse as a group of horses thunder around Tattenham Corner, still has the power to shock today, just as it did a century ago.

Since then, many theories about Emily’s intentions that day have been aired: was her act, as many have claimed, a wanton act of suicide, or did the coroner get it right when he declared that her death was a result of ‘misadventure’ caused by Emily ‘wilfully running’ onto the course while a race was in progress? Were the suffragists and the militants correct to claim that she went to Epsom as a willing martyr to the cause that she so passionately believed in? So much time has elapsed since that day, and so many claims and counter-claims have clouded the issue since, that it sometimes seems impossible that anyone will be able to uncover Emily’s true intentions.

If, with the benefit of hindsight, we stop to look analytically at the headlines in the media immediately after Emily was carried off the course, and taken to the Cottage Hospital at Epsom, we will see that there were two powerful factions scrambling to gain the moral high ground in the media. Firstly, there were the strident voices of Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU)’s very efficient publicity machine, never slow to take advantage of any situation that gave them column inches in the newspapers. They knew very well that the last thing the government wanted was for their movement to have a martyr around whom to rally the masses to their banner. Secondly, frantically snapping at their heels, were the government’s spin doctors, men who would do whatever it took to ‘spike’ the women’s cause – and the easiest way to do that was to deride and belittle the woman who was, by then, lying unconscious at death’s door, declaring her actions suggestive of a suicidal fanatic.

Emily died four days after the collision – and the full might of the WSPU’s publicity machine can also be seen in action at the funeral. One can only marvel at the logistics that must have been involved in putting the magnificent funeral arrangements together: they were on a scale equivalent to a state funeral, perhaps comparable to the funeral of Princess Diana. What the organisers achieved, at such short notice, was nothing less than a stage-managed masterpiece. Her cortège left the Cottage Hospital at Epsom on its way to London, and processed to a memorial service in Bloomsbury.

After the service, the cortège then processed back across London, heading north aboard a special train – one which, en route, was delayed at every station by waiting crowds paying homage to the fallen suffragette. Finally, the train arrived in her ancestral home in Northumberland for a private funeral service in St Mary’s church. The Illustrated Chronicle of Monday, 16 June 1913 reported the names of the family members in the cortège (with my research in parentheses following). They were:

First Carriage

• Mrs Davison, mother (formerly Margaret Caisley of Morpeth)

• Madame de Baecker, sister (formerly Letitia Charlotte Davison)

• Mrs Lewis Bilton, cousin (formerly Jessie May Caisley, also known as ‘Mamie’, the daughter of Dorothy Caisley of Morpeth and part of the Caisley/Bilton line)

• Miss Morrison, late companion of Miss Davison. (The Morrisons are related by marriage to both the Caisley/Bilton and Davison/Bilton descent lines. Miss Morrison and Emily Wilding Davison were following the family tradition of younger females becoming servants or companions in the households of older family members, as will be seen later in this book.)

Second Carriage

• Mr and Mrs Caisley of Morpeth, aunt and uncle (William Caisley and his wife, formerly Elizabeth, Isabella Blackhall)

• Mr J. Wilkinson, uncle (husband of Emma Caisley, Margaret Davison’s youngest sister, Caisley/Wilkinson descent line)

• Mrs H. Redpath of Ashington, cousin (formerly Elizabeth Wood, the third wife of Henry Redpath and the daughter of Robert Wood of Widdrington and Isabella Caisley of Morpeth, Caisley/Wood descent lines)

Third Carriage

• Councillor and Mrs Robert Wood, cousins (Robert Wood was the son of Robert Wood and Isabella Caisley. His wife was formerly Wilhelmina Jackson of Morpeth, Caisley/Wood descent line)

• Mr Lewis Bilton and Mrs Bell, cousins (Mr Lewis Bilton was the husband of Jessie May Caisley (‘Mamie’), who rode in the first carriage. Mrs Bell was formerly Emily Wilkinson, the daughter of John Wilkinson and Emma Caisley)

This rather battered old image shows Emily Wilding Davison’s funeral procession approaching St Mary’s church, Morpeth. ‘I have fought the good fight,’ says the banner. The Morpeth Herald’s report of the funeral ran thus: ‘MISS E. DAVISON’S FUNERAL: VAST CROWD WITNESSES IMPRESSIVE SPECTACLE … Last Sunday was one of the most noteworthy days in the history of Morpeth. There was interred, in the parish churchyard, the late Miss Emily Wilding Davison, of Morpeth and Longhorsley, whose exploit in stopping the King’s horse during the race for the Derby on June 4 cost her her life.’

This list paved the way to the discovery of the present-day descendants of Emily Wilding Davison. Other members of the Davison line, it is believed, also attended the London and Morpeth services, though alternative travel arrangements must have been made for them.

At Morpeth churchyard Emily’s mother insisted that her daughter’s coffin be handed over to her family, and to her male cousins (who were her pallbearers), at the lychgate. Just three local suffragettes were allowed into the churchyard, to wait beside the Davison burial plot during the private funeral service. There they folded the hand-made banner that the Morpeth suffragettes traditionally unfurled to greet Emily every time she returned to the town: ‘Welcome Home, Northumberland’s Hunger Striker,’ it said. Her banner was reverently laid on her coffin and interred with her. Her burial was akin to that of a soldier: she was buried wearing her suffrage medals. With her symbolic grave goods, Northumberland’s fallen warrior was laid to rest with all due honour bestowed on her by the nation’s suffragists, all of whom had been her comrades in arms. It was an outstanding publicity achievement, the like of which the small town of Morpeth had never seen before – nor would it see such a day again. It is possible, thinking logically, that such funeral plans were already on the WSPU’s drawing board: there had been increasing fears over the frail state of Mrs Pankhurst’s health. Had the militants efficiently swung into action, putting the previously conceived plans into action at a moment’s notice? If so, they had pulled off the coup of a century in the process.

The funeral at Morpeth. (With thanks to Pat and Gordon Shaw)

Floral tributes at Emily’s grave. (Maureen Howes)

Emily wearing her suffrage medals. (Bilton Archive)

Amidst the clamour of the WSPU and the protests of the government, one set of voices remained silent: those of the suffragette’s family and her closest associates. How did they respond to the unprecedented media frenzy that engulfed them after Emily’s shocking injury and tragic death? With an old border tactic: they closed ranks, refusing to feed an insatiable media as a show of support to Margaret Davison, née Caisley, Emily’s mother, and holding firm against all attempted intrusions. They (and their descendants) have maintained a dignified and defensive silence to this day, resisting the barrage of hype and hysteria surrounding the death of their much-loved ancestor. Nancy Ridley, author of A Northumbrian Remembers (1970), was one person who encountered that defensive wall when she came to the area to find out more about Emily: ‘There seems to be a conspiracy of silence about the Davison family in Morpeth,’ she wrote. As yet, the family’s side of the story has not been told – but this book, I hope, will finally give these family members a united platform of their own, allowing them to share a fascinating glimpse of the real woman behind the enigma, the woman who their parents and grandparents knew.

Research Begins

IN SEPTEMBER OF 2002, in Morpeth’s County Hall, a small group of dedicated locals and county officers and councillors began to plan the ninetieth anniversary tribute to Emily Wilding Davison, which was to be held in June 2003. The results of their dedication would begin to change many of the negative attitudes surrounding the event at Epsom. The chair of the committee, Mrs Sue Coulthard, a county council officer, had instinctively known that beginning to celebrate Emily’s life on each International Women’s Day, as part of the service at St Mary’s, would begin to bring the suffragette’s image into the twenty-first century.

That was when I made my decision to become the committee’s voluntary researcher and genealogist, a job which became a roller-coaster journey of discovery that would completely take over my life for the next ten years. It has been my privilege to be at the heart of this tantalizing family-history detective story as I carefully fitted together the many missing pieces. In the process I came across the unbelievable truth relating to the Epsom protest – and realised that Emily had never, in any way whatsoever, contemplated committing suicide at Epsom.

As I researched, my computer became the hub of an informal family-information exchange as long-lost Davison and Caisley descendants came to light. Together we would have many interesting email discussions. In particular, I remember one discussion with a gentleman in Australia named Geoffrey Davison. Geoffrey became one of my staunchest supporters, and he later proved to be the titular head of Emily Wilding Davison’s family line. In June 2004 we discussed Emily’s life, and the information I had uncovered – that Emily was an Oxford graduate with a family connected to the highest levels of society, part of a line of builders and pioneers whose influence stretched from the North East and the Scottish borders to India, Australia and even Mongolia. As he put it (and rather well, I thought), ‘She was not a “nutter” … This was not a sudden surge of blood to the head by some silly, naïve thrill-seeker. From her family and education she understood politics and … centres of power … Beyond anything else, she never intended to die at Epsom.’

Mrs Johnstone of Morpeth, a Caisley/Wood descendant, shares Geoffrey’s views. ‘Whenever I read about Aunt Meggie,’ she said, ‘I can never recognise her: she had a wonderful life in the south, and they spent every summer in their shooting lodge in Aberdeenshire. Where is all that other rubbish coming from?’