Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

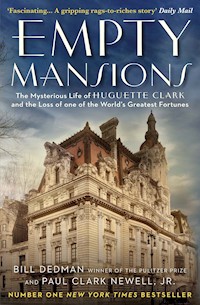

SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2014 SPEARS BOOK AWARDS - FAMILY HISTORY CATEGORY Empty Mansions is a rich mystery of wealth and loss, connecting the Gilded Age opulence of nineteenth-century America with a twenty-first-century battle over a $300 million inheritance. At its heart is a reclusive heiress named Huguette Clark, a woman so secretive that, at the time of her death at age 104, no new photograph of her had been seen in decades. Though she owned palatial homes in California, New York, and Connecticut, why had she lived for twenty years in a simple hospital room, despite being in excellent health? Why were her valuables being sold off? Was she in control of her fortune, or controlled by those managing her money? Huguette Clark was the daughter of self-made copper industrialist W. A. Clark, nearly as rich as Rockefeller in his day, a controversial senator, railroad builder, and founder of Las Vegas. She grew up in the largest house in New York City, a remarkable dwelling with 121 rooms for a family of four. She owned paintings by Degas and Renoir, a world-renowned Stradivarius violin, a vast collection of antique dolls. But wanting more than treasures, she devoted her wealth to buying gifts for friends and strangers alike, to quietly pursuing her own work as an artist, and to guarding the privacy she valued above all else. Empty Mansions reveals a complex portrait of the mysterious Huguette and her intimate circle. We meet her extravagant father, her publicity-shy mother, her star-crossed sister, her French boyfriend, her nurse who received more than $30 million in gifts, and the relatives fighting to inherit Huguette's copper fortune. Richly illustrated with more than seventy photographs, Empty Mansions is an enthralling story of an eccentric of the highest order, a last jewel of the Gilded Age who lived life on her own terms.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EMPTY MANSIONS

First published in the United States of America in 2013 by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr, 2013

The moral right of Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All credits for reproductions of photographs can be found on pages 431–435.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-476-1

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78239-477-8

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-478-5

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

FOR HUGUETTE.

P.N. and B.D.

CONTENTS

W. A. Clark Family Tree

Introduction

An Apparition

Still Life

CHAPTER ONE

THE CLARK MANSION, Part One

CHAPTER TWO

THE LOG CABIN

CHAPTER THREE

THE COPPER KING MANSION

CHAPTER FOUR

THE U.S. CAPITOL

CHAPTER FIVE

THE CLARK MANSION, Part Two

CHAPTER SIX

907 FIFTH AVENUE, Part One

CHAPTER SEVEN

907 FIFTH AVENUE, Part Two

CHAPTER EIGHT

BELLOSGUARDO

CHAPTER NINE

LE BEAU CHATEAU

CHAPTER TEN

DOCTORS HOSPITAL

CHAPTER ELEVEN

BETH ISRAEL MEDICAL CENTER

CHAPTER TWELVE

WOODLAWN CEMETERY

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

SURROGATE’S COURTHOUSE

EPILOGUE

THE CRICKET

Authors’ Note

Acknowledgments

Selected Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Appendix: Siblings of W. A. Clark

Appendix: Inflation Adjustment

Index

INTRODUCTION

WE CAME TO THIS STORY by separate paths, one of us by accident and one by birth.

Bill Dedman

I STUMBLED INTO THE MYSTERIOUS WORLD of Huguette Clark because my family was looking for a house, and I got a little out of our price range.

In 2009, my wife’s job had been transferred from Boston to New York City, but we wanted to keep in touch with the charms and idiosyncrasies of New England: old stone walls, Colonial houses on country corners, thrifty Yankees who save an r sound by keeping their wool socks in a “draw,” yet put the r to good use when they “draw’r” a picture. While renting we looked at small towns in Connecticut, about an hour northeast of the Empire State Building. Although property values had plunged in the Great Recession, houses came in only two flavors: those we didn’t like and those we couldn’t afford.

One evening, frustration turned to distraction. I began to scan the online listings for houses we really couldn’t afford, an exercise in American aspiration. Although some names were familiar—professional talkers Don Imus and Phil Donahue were having trouble selling waterfront mansions on Long Island Sound—other names sent me to Google. One fellow had been able to purchase an $8 million house by selling boxers and briefs on the Internet. (“Buy underwear in your underwear.”) I was gobsmacked, however, by the property at the top of the charts.

The most expensive house for sale in Connecticut, in the tony town of New Canaan, was priced at $24 million, marked down from $35 million. Billed as Le Beau Château, “the beautiful castle,” this charmer had 14,266 square feet of floor space tucked into fifty-two wooded acres with a river and a waterfall. Its twenty-two rooms included nine bedrooms, nine baths, eleven fireplaces, a wine cellar, elevator, trunk room, walk-in safe, and a room for drying the draperies. The property taxes alone were $161,000 a year, or about four years’ income for a typical American family. I didn’t recognize the name of the owner, Huguette Clark. Was that a he or a she?

There was an odd note in the records on the town’s website: Le Beau Château had been unoccupied since this owner bought it. In 1951. That couldn’t be right. Who could afford to own such a house and to not live in it for nearly sixty years? And why would anyone do that?

A beautiful castle wasn’t quite in the job description of an investigative reporter, but the next morning, I drove over to New Canaan.

On a winding, narrow lane called Dan’s Highway was a tiny handmade marker for No. 104 and a warning sign, “PRIVATE PROPERTY NO TRESPASSING VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED.” Behind a low red-brick wall with white peeling paint sat two tiny brick cottages. Between them a driveway ran under a rusty gate into the trees and curved out of sight. If there was a beautiful fairy-tale castle, it was deep in the wood. The property showed no sign of humans, only wild turkeys, deer, and birds. It seemed more like a nature preserve than a home. There was no mailbox, no name, no buzzer. Leaning over the wall, I rapped on the window of one of the cottages.

Out shuffled an unshaven man in his white undershirt, a sleepy fellow who introduced himself as the caretaker, Tony Ruggiero. Eighty years old but muscled, he said he used to be a boxer and had sparred once with Rocky Marciano, but now he was watching over “Mrs. Clark’s house.” He wouldn’t open the gate, but he said the house though empty was well cared for. He’d never met the owner in his more than twenty years. All he knew was that his paycheck came from her lawyer in New York City.

Ruggiero thought of something and ducked back inside. He brought out a newspaper clipping from the New York Post. An auction house had sold a painting for $23.5 million, Renoir’s In the Roses, of a woman seated on a bench in a garden, and the newspaper said the portrait came from “the estate of Huguette Clark.” Ruggiero kept pointing to those words “the estate of.”

“Let me ask you a question,” he said. “Do you suppose she’s been dead all these years?”

. . .

Finding Huguette Clark’s name on an Internet discussion board from Southern California, I discovered that Le Beau Château wasn’t her only orphaned house. She had a second, grander home in Santa Barbara, a vacation estate on twenty-three cliff-top acres fronting the Pacific Ocean. But this home was definitely not for sale. A newspaper said she had turned down $100 million some years back. The lush estate was called Bellosguardo, meaning “beautiful lookout.” According to the Internet chatter, Huguette had not been seen there in at least fifty years, but the 21,666-square-foot mansion was immaculately kept, with 1930s sedans still in the garage, and the table set just in case the owner should visit.

Though I didn’t put much stock in the tale, my curiosity was piqued. Out in Santa Barbara for a business trip a while later, I tried to visit Bellosguardo. The property is hidden on a bluff, separated by a high wall from the Santa Barbara Cemetery, allowing even the dead barely a glimpse of the great house. The back gate to Bellosguardo was open, however, so I walked up the serpentine driveway. At the top of the hill, several gardeners were at work. The main house was out of sight behind a stand of trees. Suddenly, a golf cart barreled toward me, driven by a sturdy man in his fifties giving instructions on a walkie-talkie. He identified himself as the estate manager, C. John Douglas III, and pointed out the half dozen No Trespassing signs. As he sent me back down the driveway, mentioning something about the police, he divulged only two facts: He had worked for “Mrs. Clark” for more than twenty-five years, and he had never met her.

Talking through the locked gate, Douglas was in no mood to help solve a mystery. “I’m just sorry,” he said dismissively, “that this is what you have to do to put food on the table for your children.”

My family was indeed worrying a bit about curiosity getting the best of me. After all, my wife and I did meet during a prison riot, two journalists breaking into the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary to get a better view of the hostages. After I told my brother, a movie buff, about the empty mansions and the search for their mysterious owner, he sent an email with a whispered word: “Rosebud.”

Sure, make fun. But where was Huguette Clark? Where did these vast sums of money come from, and why were they being wasted?

. . .

Public records led me to a third residence. Huguette Clark owned not one but three apartments in a classic limestone building in New York City, at 907 Fifth Avenue, overlooking Central Park at Seventy-Second Street. It’s a neighborhood of legend and fantasy, near the statue of Alice in Wonderland and the pond where the boy-mouse Stuart Little raced sailboats. Yes, sir, said No. 907’s uniformed doorman, in his Russian accent, this is “Madame Clark’s building.” But no, he hadn’t seen Madame or any other Clarks for about twenty years, although he had carried groceries for Martha Stewart, who had a pied-à-terre in the same building. He shrugged, as if to say that doormen see a lot of strange things.

Neighbors and real estate agents filled in a few details. Huguette Clark’s apartments took up the entire eighth floor of the building and half the twelfth, or top floor, for a grand total of forty-two rooms and fifteen thousand square feet on Fifth Avenue, the most fashionable street in the most expensive city in America. Her bill from the co-op board for taxes and maintenance was $342,000 a year, or $28,500 a month. Although they’d never seen Huguette Clark, neighbors said they’d heard that her apartments were filled with an amazing collection of dolls and dollhouses. And paintings, too, even a Monet. One neighbor let me into the quiet elevator lobby of Huguette’s eighth floor, where rolls of surplus carpet were stored. I rang the buzzer, and no one answered. It didn’t seem like a place where anyone would keep a Monet.

So this Huguette Clark owned homes altogether nearly the size of the White House. Where on earth did she reside? And why did she keep paying for this fabulous real estate if she wasn’t using it? If I couldn’t find out where Huguette was, then perhaps I could at least discover who she was.

. . .

It turned out that I had wandered through a portal into America’s past. Long past. Huguette Clark, then 103 years old, was the heiress to one of America’s greatest fortunes, dug out of the copper mines of Montana and Arizona, the copper that carried electricity to the world. Her father, William Andrews Clark, sounded like the embodiment of the American dream: a Pennsylvania farm boy born in a log cabin, a prospector for gold, a banker, and a U.S. senator from Montana. W. A. Clark was also a railroad baron, connecting the transcontinental lines to a sleepy California port called Los Angeles. And along the way, he auctioned off the lots that became downtown Las Vegas.

The newspapers of the early 1900s couldn’t decide who was the wealthiest man in America in that age before the personal income tax. The New York Times calculated in 1907 that if you counted only the money already in the banks, oilman John D. Rockefeller was tops. However, if you also included the wealth still to be brought up from underground, the Times decided that copper king W. A. Clark might prove to be richer than Rockefeller.

W. A. Clark also had one of the more controversial political careers in American history. He was forced to resign from the U.S. Senate for paying bribes to get the seat in the first place. Undeterred, he was reelected. While serving in the Senate in 1904, the widower with grown children shocked the political world by revealing a secret marriage to a woman thirty-nine years his junior. At the time of the announcement, the senator and Anna LaChapelle Clark already had a two-year-old daughter, Andrée. The woman I was looking for in 2009, Huguette Clark, was the second child of that marriage, born in 1906 in Paris.

So the name was French: Huguette. The pronunciation took some getting used to, and my Southern accent still has trouble with it. I’m told that the French “u” sound doesn’t exist in English. It’s not “hue-GET” with an initial “H” sound, nor “you-GET” with a “Y,” but somewhere close to “oo-GET.” When W. A. Clark died in 1925, he left an estate estimated at $100 million to $250 million, worth up to $3.4 billion today. One-fifth of the estate went to eighteen-year-old Huguette, who was depicted in cartoons as a spoiled poor little rich girl. In the histories and magazine cover stories of his time, the word most often associated with W. A. Clark was “incredible.” But after his death, his businesses were sold, and the Clark name faded. He may be the most famous American whom most Americans today have never heard of. Now Huguette, who inherited one-fifth of the copper-mining fortune, also was missing.

The length of history spanned by father and daughter is hard to comprehend. W. A. Clark was born in 1839, during the administration of the eighth president of the United States, Martin Van Buren. W.A. was twenty-two when the Civil War began. When Huguette was born in 1906, Theodore Roosevelt, the twenty-sixth president, was in the White House. Yet 170 years after W.A.’s birth, his youngest child was still alive at age 103 during the time of the forty-fourth president, Barack Obama.

Well, still alive, as far as I knew.

In researching stories about Huguette for the NBC News website, I gradually pieced together that she was indeed alive and had been living for twenty years in self-imposed exile in hospital rooms in Manhattan, although she was said to be in good health. For her own reasons, she had separated herself from the world. She was so reclusive that one of her attorneys, who had handled her business for more than twenty years, had never spoken to her face-to-face, talking to her only on the phone and through closed doors.

And that was, for me, the end of the hunt. I wrote about the mansion mystery, but I wasn’t going to barge into a shy old woman’s hospital room.

. . .

Then readers started emailing with hints of something nefarious, and the mansion mystery morphed into a criminal investigation. One of Huguette’s possessions—one of the rarest violins in the world, a Stradivarius—had been sold for $6 million, and the buyer had been made to promise that he wouldn’t tell anyone for a decade where he got it. Meanwhile, a nurse had somehow received millions of dollars in gifts from Huguette’s accounts. Huguette’s accountant was a felon and a registered sex offender, caught trolling to meet teenage girls over the Internet. And that accountant, along with Huguette’s attorney, had already inherited the property of another elderly client.

After my updates about these developments, the Manhattan district attorney had the same questions our readers did: Why would Huguette be selling precious possessions unless she was down to her last copper? Was this eccentric centenarian, who had lived in a hospital for twenty years, competent to manage her affairs? Were her attorney and accountant in line to inherit her fortune, said to be worth more than $300 million?

The reclusive heiress who had withdrawn from the world suddenly had the modern media machine at her doorstep. Huguette Clark was featured on the Today show and on page one of the New York tabloids. Although she had been born in the silent film era, she became after her 104th birthday a trending topic of searches on Google and Yahoo, with a biography on Wikipedia, fan pages on Facebook, and a lavish story on the front page of The New York Times.

Huguette had been famous in her childhood and was famous again more than a century later, but in between she’d been a phantom. The last known photograph of her, a snapshot of an uncomfortable heiress in furs, jewels, and a cloche hat in the fashionable bell shape, had been taken in 1928. She had managed to escape the world’s gaze since then. How? And, more important, why?

Urging further investigation, one of Huguette’s own bankers confided to me, “The whole story is utterly mysterious but equally frightening. It has all the markings of a massive fraud. Poor Miss Clark sounds like one in a long list of rich, isolated old ladies taken advantage of by supposedly trustworthy advisers.”

If that’s what really happened.

. . .

During my research I was fortunate to meet one of Huguette’s relatives. Paul Clark Newell, Jr., is not in line for a claim to her estate, but he was interested in tracing the family history. And he’d gotten a lot closer to Huguette than I had. For one thing, he’d had the good sense to look for her number in the phone book.

Paul Newell

HUGUETTE CLARK WAS MY FATHER’S FIRST COUSIN, although she preferred to identify herself to me as Tante Huguette, using the French word for aunt. My father, Paul Clark Newell, remembered Senator W. A. Clark, who was his uncle and Huguette’s father. This famous uncle often visited the Newell family home in Los Angeles. In the last years of his life, my father took up a long-delayed mission, writing a biography of Senator Clark. Unfortunately, his health was failing, so only fragments of that work were completed.

After my father’s death, I began to organize our family archives, to visit museums and historical societies, and to develop friendships with relatives who had known W.A. and his second wife, Anna. A few had even met the reclusive Huguette. From the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which held the senator’s art collection, I learned that Huguette was still alive. She was a generous patron to the Corcoran, sending handwritten checks while insisting that her gifts be attributed to “Anonymous.”

Huguette had always been a mysterious presence in family lore. Though they were essentially the same age, my father had never met her, even when he was a guest in Senator Clark’s monumental mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York. When I was a youngster, on family trips on the Pacific Coast Highway through Santa Barbara, my father would point out a promontory by the sea and tell me of Bellosguardo, the great Clark vacation estate. I had heard him speak of Huguette’s shyness and reclusive tendencies, but I knew little more about her.

Years later, while traveling through Santa Barbara in the 1990s, I checked under Clark in the phone directory, and to my great surprise I found not one but two listings for Huguette M. Clark, giving her phone numbers and street address on the oceanfront Cabrillo Boulevard. Remarkable openness, I thought, for someone whose life was enveloped in secrecy. I dialed one of the numbers and reached her estate manager, John Douglas. He told me a little about his work and said that Madame Clark was a wonderful person to work for, though he said he had never met her. I asked how I might make contact with Huguette, and he provided me with the name of her attorney in New York, Donald Wallace. In November 1994 I wrote to her, through Wallace, introducing myself and saying that I hoped she might cooperate in my family research.

Within ten days I received a voice mail message, chipper and tantalizing. “Hello, Paul, this is your Aunt Huguette. I’m sorry I missed you, Paul, because I do want to speak with you. I’ll call you back soon, Paul, so we can talk. Bye-bye.”

Her voice was high-pitched, with a hint of a foreign accent, perhaps reflecting her early years in France or revealing a minor speech impediment. Although she was then eighty-eight years old, her voice was steady. She left subsequent messages, but never a phone number to call her back. Why not provide me with her phone number? I pictured her at home in her commodious apartment on Fifth Avenue. Surely she employed a butler or secretary to receive and screen her calls. I telephoned her attorney to inquire about the situation.

“She’s not going to provide you a number,” he replied curtly.

She missed me again the next month, leaving this message:

Hello, Paul, this is your Aunt Huguette, and I did call the other number, but I didn’t get an answer. So I will call you up soon again, because just now I have the chicken pox—of all things to get at my age. Imagine! So, anyway, I’m getting along fine. The fever went down and everything’s okay. And thank you for the photos. Your daughter is beautiful! And your little grandson, Eric—

At that point, the message timed out. Surprisingly, this aged relative, so well known in the family for being reclusive and on guard, seemed comfortable going on informally about personal medical matters and inquiring about my immediate family even though we had never met. But I still didn’t have her number.

I continued writing to her through the next year, and in October 1995 I let her know I would be in New York, and gave her the phone number of my hotel. I had accepted an invitation from one of my Clark cousins, André Baeyens, at the French consulate up Fifth Avenue from Huguette’s apartment. André, a great-grandson of the senator and a career diplomat, was the French consul general in New York. Huguette had asked André to contact me, and we became friends. Upon my return to my hotel room that night, around eleven, the phone rang.

“Hello, Paul, this is your Aunt Huguette.”

At last, nearly a full year after my initial letter, we were in conversation. We remained in conversation for nine years. We talked about six times a year. Sometimes the calls were brief, just a few minutes of light chatter, but on other occasions we talked for a half hour or longer. Selections from our chats are included throughout this book as pieces entitled “In Conversation with Huguette.”

She shared with me her favorite books and some of her memories. We discussed current events and family history. And she extended to me the rare treat of visiting her Santa Barbara home, Bellosguardo. I would call her attorney to arrange a time, and Huguette would call as requested, sometimes a few minutes early. What she never shared was her phone number.

Bill Dedman and Paul Newell

IN MAY 2011, just two weeks before her 105th birthday, Huguette Clark died in Beth Israel Medical Center in Manhattan. Court records soon answered one mystery while raising another. Huguette had not signed “a will” to distribute her fortune, but had signed two wills with contrary instructions. Both had been signed in the spring of 2005, when she was nearly ninety-nine.

The first will left $5 million to her nurse and the rest of her fortune to her closest living relatives, who would have inherited anyway if she had signed no will at all. These heirs were not named in the document.

Six weeks later, Huguette had signed a second will, leaving nothing to her relatives. She split her estate among her nurse, a goddaughter, her doctor, the hospital, her attorney, and her accountant, but directed that the largest share go to a new arts foundation at Bellosguardo, her California vacation home.

Thus began a court battle—with more than $300 million at stake—to determine Huguette’s true intentions. Nineteen relatives, from her father’s first marriage, challenged her last will, saying that Huguette was a victim of fraud, that she was mentally ill, unable to understand what she had signed.

. . .

In Empty Mansions, we have joined together to explore the mystery of Huguette Clark and her family. Our aim is to tell their story honestly, wherever it leads. We believe it’s a story worth telling, not only for Huguette’s sake but because of the light it may throw on American history.

On one level, our tale of the copper king and his family traces the rise and fall of a great fortune. Americans are familiar with the names Rockefeller and Carnegie and Morgan, but why has W. A. Clark nearly vanished from history? At what cost, with what sacrifices, did he achieve wealth and political power? What sort of life did his young wife, Anna, and their daughters, Andrée and Huguette, enjoy amid such incredible wealth and public scrutiny? Why did Huguette withdraw from the public eye? In her old age, was she competent to control her finances or was she, as her relatives assert, controlled by her nurse and her money men? And who would, or should, inherit her fortune?

Yet on another level, above such worldly considerations, the story of the Clarks is like a classic folk tale—except told in reverse, with the bags full of gold arriving at the beginning, the handsome prince fleeing, and the king’s daughter locking herself away in the tower. The fabulous Clarks may teach us something about the price of privacy, the costs and opportunities of great wealth, the aftermath of achieving the American dream. They can take us inside the mountain camps of the western gold rush, inside the halls of Congress, the salons of Paris, and the drawing rooms of New York’s Fifth Avenue amid the last surviving jewels of the Gilded Age.

This book is drawn from interviews, private documents, and public records, as described in the authors’ note and line-by-line notes at the back. We have invented no characters, imagined no dialogue, put no thoughts into anyone’s head. The sources include more than twenty thousand pages of Huguette’s personal papers and the testimony of fifty witnesses in the legal contest for her fortune. Though no work of non-fiction can pretend to map anyone’s interior terrain, the Clarks have left enough bread crumbs to lead us back into their fairy-tale world.

AN APPARITION

DR. HENRY SINGMAN, an internist, was making an emergency house call on a new patient on New York’s old-money Upper East Side. It was a sunny early-spring afternoon, March 26, 1991. Dr. Singman had received a call from a retired colleague, whose former patient had sent out an SOS.

At the luxury apartment building at 907 Fifth Avenue, the uniformed doorman greeted the doctor, leading the way up the marble steps and through the lobby with its elegantly coffered ceiling. The elevator, paneled in mahogany like a plutocrat’s library, carried them to the eighth floor. The doorman then did something he had never dared before. He unlocked Apartment 8W, admitting the doctor.

Drawn shades blocked the sunlight from Central Park. A single candle lit the entryway—an art gallery nearly forty feet long. The parquet floor was an obstacle course of French dollhouses and miniature Japanese castles. Mannequins populated a side room, a gaggle of geishas wearing kimonos. The draperies were green silk damask and red velvet, the furniture Louis XV gilded oak, the paintings signed by Renoir, Cézanne, Degas, Manet, Monet.

In the half-light, Dr. Singman came face-to-face with “an apparition,” a tiny woman, nearly eighty-five years old, with thin white hair and frightened eyes the color of blue steel. She wore a soiled bathrobe and had a towel wrapped around her face.

His medical notes give the grim details. The patient was suffering from several cancers, basal cell carcinomas that had gone untreated for quite a while. She was missing the left part of her lower lip, unable to take food or drink without it gushing from her mouth. Her right cheek had deep cavities. Where her right lower eyelid should have been, there were large, deep ulcers exposing the orbital bone. She weighed all of seventy-five pounds, “looked like somebody out of a concentration camp,” and “appeared nearly at death’s door.”

Dr. Singman urged her to go immediately to a hospital. The patient chose Doctors Hospital, which wasn’t Manhattan’s finest but was close to a friend’s apartment. The patient had no insurance, so her attorney sent over a $10,000 check to the hospital, and the ambulance came that night.

The patient never saw this apartment again, except in photographs. Though she recovered to excellent health, she chose to spend the next twenty years and nearly two months, or exactly 7,364 nights, in the hospital.

As she left her home that spring evening in 1991, Huguette Clark insisted on being carried through the lobby and down the marble steps on a gurney, held high above the shoulders of the ambulance men, like Cleopatra riding on a litter—not for ceremony but for privacy, so the doormen and her neighbors couldn’t see her face.

STILL LIFE

BELLOSGUARDO REMAINS TODAY as Bellosguardo was the last time Huguette saw it sixty years ago. The Clark summer estate in Santa Barbara, with its sweeping view of the shimmering Pacific, has been lovingly preserved since the early 1950s at the cost of only $40,000 per month.

Inside the gray French mansion, in the back of the service wing in a room off the kitchen, on the green tile floor lies a white sheet of paper. This typeset sign bears the signature of one of the housemen and has been in place for more than a decade now. It marks the former location of a piece of furniture.

ON 29 NOVEMBER 2001,

I MOVED A WHITE,

WOODEN STEP STOOL FROM

THIS ROOM TO THE MAIN

WING ELEVATOR AS AN AID

TO RESCUE IN CASE THE

ELEVATOR GETS STUCK.

Harris

Out in the massive garage, formerly a carriage barn and staff dormitory with a ballroom for dances, the automobile shop was once the domain of Walter Armstrong, the Scottish chauffeur for the Clarks. With no Clarks to drive most of the time, Armstrong filled the quiet afternoons at Bellosguardo with the low drone and high melody of his bagpipes.

Armstrong is long gone. After he retired, Huguette paid him his full salary as a pension until he died in the 1970s. Then Huguette paid the pension to his widow, Alma, until she died in the 1990s. But two of the automobiles that Armstrong lovingly cared for are still here, carefully preserved. Huguette turned down repeated offers to buy them.

On the right is a 1933 Chrysler Royal Eight convertible, its top perpetually down, with black paint and cream wheels. The chrome hood mascot of a leaping impala soars over a massive front grille. Huguette recalled Armstrong letting her drive the convertible on the coast road in the Santa Barbara summers of the Great Depression.

On the left is an enormous black 1933 Cadillac V-16 seven-passenger limousine. Its golden goddess hood ornament gleams under the garage’s chandelier. Spare tires are affixed at the front of the running boards. Pull-down shades, like those in a drawing room, are ready to provide privacy to occupants of the coach.

On both automobiles, the yellow-and-black California license plates say 1949.

CHAPTER ONE

THE CLARK MANSION

. . .

PART ONE

THE MOST REMARKABLE DWELLING

HUGUETTE AND ANDRÉE, daughters of the multimillionaire former senator W. A. Clark, arrived in New York Harbor in July 1910, immigrants to their own country. They had sailed from Cherbourg, France, in first-class cabins on the White Star liner Teutonic. Wearing broad-brimmed sun hats, the Clark girls posed for newspaper photographers on the pier. Andrée, the adventurous eight-year-old brunette, looked confidently at the cameras, as her tag-along sister, blond four-year-old Huguette, looked down uncertainly.

Huguette’s first day in America was filled with conjecture and misinformation. Reporters wrote that the heiresses didn’t speak a word of English. Yet their parents were born in Pennsylvania and Michigan, and the girls held American passports, citizens since birth. In fact, they were being well educated by private tutors and governesses, with lessons in three languages: English, Spanish, and French.

Huguette Marcelle Clark was born in Paris on June 9, 1906. Her parents’ apartment was on avenue Victor Hugo, at No. 56, a short walk down the wide, tree-lined avenue from the Arc de Triomphe. The baby girl, like the avenue, was named for France’s beloved novelist, poet, and dramatist, who had lived just down the block in his last days. The child’s name may also have been a nod to her father’s French Huguenot ancestry. As a young woman, Huguette sometimes signed her name Hugo, and some of her friends called her Hugs. Andrée was nearly four when Huguette was born. When she had been told that a baby sister was due, Andrée said to her mother, “Let me think it over.” Even one hundred years later, Huguette loved to laugh at her sister’s cleverness. Huguette’s father was old enough to be her great-grandfather. When Huguette was born, W.A. was a vigorous sixty-seven with four grown children from his first marriage, while Huguette’s mother, Anna LaChapelle Clark, was only twenty-eight.

Although both parents had accompanied the girls on the ocean crossing, W.A. is the proud parent in the photographs on the pier. Anna stayed off to the side out of the camera’s view. In the rare public photos of her, Anna appears standoffish, coolly looking out from under her tilted formal hats. But in the private photos in Huguette’s albums, we see another Anna. Wearing her fashionable Continental dresses with a sash around her waist, she smiles warmly, playfully.

When the family arrived in 1910, they had no house in New York to go to. The greatest mansion in the city wasn’t quite ready, even after ten years of construction. W.A. sent his wife and daughters west to the Rocky Mountains to Butte, Montana, where he had made his fortune in copper mining. He stayed behind in his New York apartment, sometimes spending the night in the unfinished Clark mansion, changing the plans to make it grander.

. . .

“When this modern palace is completed,” the New York World reported, “it will rival in beauty and richness the mythical palace of Aladdin.” W.A. had selected the site in 1895, paying $220,000 for the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and Seventy-Seventh Street, prominently situated in the middle of New York’s Millionaires’ Row, up the avenue from Vanderbilt and Astor, down from Carnegie. By the time it was finished in 1911, observers called it the “biggest, bulliest and brassiest of all American castles,” “the most remarkable dwelling in the world,” and “without doubt the most costly and, perhaps, the most beautiful private residence in America.”

The 121-room mansion was also Huguette’s childhood home from age five to eighteen. This was a fairy-tale castle come to life, with secret entrances, mysterious sources of music, and treasures collected from all the world. When Andrée and Huguette would arrive home in their chauffeured automobile, accompanied by a private security guard, they passed through the open carriage gates—bronze gates twenty feet high, fit for a palace.

The bottom half of the six-story Beaux Arts mansion was not so unusual in its day, and might not have stood out if it were W.A.’s bank building. But on the top half, every inch was decorated with Parisian Beaux Arts ostentation, a profusion of lions, cherubs, and goddesses. Oh, but the architects weren’t done. Soaring above the mansion was an ornate domed tower reaching nine stories, so pleased with itself that it continued to an open cupola. The overall effect was as if a lavish wedding cake had been designed in the daytime by a distinguished chef, and then overnight a French Dr. Seuss sneaked in to add a few extra layers.

Andrée and Huguette were outdoor girls. In the winter, dressed in matching red coats and red broad-brimmed hats, they went coasting down hills on sleds in Central Park. In the summer, they romped in matching sailor shirts and bloomers gathered above the knee. From any corner of the park, they had a specific home base for navigation: the tower of the Clark mansion. And when they stood in the tower itself, one hundred feet above the sidewalk, Andrée and Huguette could see all of Manhattan spread out below them.

Reporters who toured the home counted twenty-six bedrooms, thirty-one bathrooms, and five art galleries. Below the basement’s Turkish baths, swimming pool, and storage room for furs, a railroad spur brought in coal for the furnace, which burned seven tons on a typical day, not only for heat but also to power dynamos for the two elevators, the cold-storage plant, the air-filtration plant, and the 4,200 lightbulbs.

As the girls pulled into the U-shaped driveway, they rode first into an open-air main courtyard and then under an archway into a vestibule decorated with a fountain of Tennessee marble. The fountain displayed a satyr’s head projecting from a great clamshell, while two marble mermaids played in the spray. Their carriage then passed into a rotunda, where the young ladies of the house could disembark.

Mass production of the automobile had not yet begun when the plans were drawn up in 1898 by a little-known firm. By 1900, the foundation was being laid, but W.A. kept changing the plans, buying up five neighboring houses to make room for a more extravagant plan by a more famous architect, Henri Deglane, the designer of the Grand Palais in Paris.

W.A. supervised every detail of the house, every furnishing. To hurry along the work, and to keep from being gouged on the prices, in 1905 he bought the Henry-Bonnard bronze foundry, which used copper from his mine in Arizona to make the radiator gratings and door locks. When the price of white granite was raised by a quarry in North Jay, Maine, W.A. bought the quarry next door to undercut the price. He also bought the stone-dressing plant, the marble factory, the woodwork factory, and the decorative-plaster plant.

The plans were modified to include an automobile room after Ransom Olds began selling his Curved Dash Oldsmobile in 1901. After the home was occupied in 1911, photographs show carriages of both types—horse-drawn and horseless—lined up by the gate, with the automobile’s driver careful to park in front of the horse.

From the carriage rotunda, Andrée and Huguette could stop on the ground floor to see their father in his private office, situated at the street corner for maximum light. With Santo Domingo mahogany walls, the office was dominated by a Gilbert Stuart portrait above the mantel—the familiar face of George Washington now on the one-dollar bill.

Huguette’s girlhood home, the most expensive house in New York, afforded 121 rooms for a family of four. Note both types of carriages awaiting passengers at the Clark mansion on Seventy-Seventh Street at Fifth Avenue.

IN CONVERSATION WITH HUGUETTE

Saints, and religion in general, were more important to the Roman Catholic Anna and her daughters than they were to W.A. He had been a Presbyterian as a youth, then as a prosperous banker he became a more fashionable Episcopalian. Though he helped to build most of the churches in Butte, he admitted, “I am not much of a churchman.”

Huguette told me that as a child she asked her father, “Oh, Papa, why can’t you be Catholic?”

His reply: “All religions are lovely, my dear.”

—PAUL NEWELL

If Andrée and Huguette sneaked through their father’s waiting room and down the mirror-lined hallway past his office library, they could peek into the house’s male domain, a Gothic-style great hall for smoking and billiards. The room was twenty feet by ninety feet, decorated with a thirteenth-century stained-glass window from a cathedral at Soissons in France.

The billiard room had another oddity: six paintings depicting the heroism, trial, and cruel death of Joan of Arc, France’s maiden heroine. Her story was a particular favorite of Andrée’s. The French artist of these paintings, Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel, had done a children’s history of the maiden Joan, and the girls met the artist in France. At first the artist intended these paintings for a chapel near Domrémy, Joan’s birthplace. But W.A. had to have them, so instead of being on view for the faithful who made pilgrimages to honor Joan, they were hanging in W.A.’s billiard room.

The cost of building the Clark house, not counting the furnishings, had been predicted to be $3 million, which would have made it as expensive as Rockefeller’s and Carnegie’s homes combined. As so often happens with home construction projects, the cost climbed—to $5 million, then $7 million, and some newspapers said $10 million, a bill that works out to a bit more than $250 million in today’s currency. For perspective, the fifty-seven-story Woolworth Building, a neo-Gothic cathedral of commerce completed in 1913 in Lower Manhattan, cost $13.5 million, and the Woolworth would reign for nearly two decades as the tallest skyscraper in the world. Still, the Clark mansion cost no more than two years’ profits flowing from a single Clark copper mine, the United Verde in Arizona. Always watching his pennies, W.A. was able to persuade the courts to lower his property tax bill by valuing the home at only $3.5 million, on the legal theory that it was so expensive to operate that it was of no use to anyone else.

The girls could ride up to the main floor in the elevator, or climb the grand circular staircase. Made of ivory-tinted Maryland marble, the stairs wound their way through a ceiling of oak overlaid with gold leaf. At the top of the stairs, Andrée and Huguette passed two exquisite bronze statues on white marble pedestals, each showing classical Greek heroes in scenes of struggle: on the left a muscular Odysseus bending his bow to show his strength and prove his identity, and on the right a chained Prometheus enduring his endless torture, an eagle eating his liver.

From the top of the stairs, the girls could look down the hallway, of white marble with mottled Breche violette columns, to the marble sculpture hall, with its thirty-six-foot-high octagonal dome made of terra-cotta, in the center of which hung an antique Spanish silver lamp. Here the girls enjoyed playing a game of hide-and-seek. If Andrée, the braver one, climbed to the third floor and passed through an alcove to the top of the dome, she could look down to see Huguette three floors below.

IN CONVERSATION WITH HUGUETTE

On November 3, 2003, Huguette called, her voice strong and clear as usual. I thanked her for the packet of family photos she had sent and asked her about the photo of her father and his guests standing at a long dining table. She said it had been taken in the formal dining room at the Clark mansion on Fifth Avenue in 1913.

Could she tell me who the guests were? She mentioned several, including J. P. Morgan, and . . .

“Oh, what was that character’s name? Oh, yes, Carnegie. Andrew Carnegie.”

The main dining room, twenty-five feet by forty-nine feet, was about the same size as a family apartment in New York City. Above its massive fireplace, carved figures of Neptune, god of the sea, and Diana, goddess of the hunt, presided over the stone mantel, attended by cherubs, guarded at their feet by carved lions six feet tall. The ceiling set mouths agape: gilded panels carved from a single English oak supposedly harvested from Sherwood Forest. Over the door was a panel for the new Clark crest. The Clarks had no hereditary coat of arms, so W.A. sketched one out himself with elements fit for a royal house: a lion, an anchor, and a Gothic C.

Huguette recalled that her father forbade the girls to run around in the grand salon. W.A. had bought this room, alone the size of a typical house, and had it reassembled here overlooking Fifth Avenue and the woodlands of Central Park. Called the Salon Doré, or “golden room,” it gleamed with exquisitely carved and gilded wood panels made in 1770 for a vainglorious French nobleman. W.A. brought the extravagant wall panels intact from Paris, adding reproduction panels to make the square room fit into his larger rectangular space. He decorated the salon with a clock from the boudoir of Marie Antoinette. During the French Revolution, when the former queen was under house arrest at Paris’s Tuileries Palace, this gilded clock counted down the hours before her imprisonment and execution. A century later, this room was reserved for formal occasions. The Clark girls were allowed to play in the smaller room next to it, sitting on the Persian carpet of the petit salon.

The girls found more wonders in the tower. Huguette recalled playing hide-and-seek with Andrée there, one hundred feet above the street, discomforting their mother terribly. The tower held its own secret, a suite held in reserve for dark days. This was the quarantine suite, a valued space in these years before antibiotics, with bedrooms and its own kitchen, a refuge in case of a pandemic.

Coming down from the tower, the girls passed the servants’ quarters on the fifth and sixth floors. The nursery on the fifth floor was separated into night and day nurseries, each with its own kitchen. A gentleman from The New York Times who toured the new house explained, “As the Senator and Mrs. Clark have but two small children, the facilities of these spacious rooms will not be overtaxed.” On the fourth floor was the Oriental room, with the senator’s treasures from the East, and some of the twenty-five guest rooms. These higher floors were designed at first to hold apartments to accommodate W.A.’s grown children from his first marriage, but they already had their own homes, and the apartments were converted to other uses.

Brought over from Paris, the golden room, or Salon Doré, was a bit too formal for Andrée and Huguette to play hide-and-seek in.

There were many nooks for Andrée and Huguette to explore. The private area of the mansion, the part reserved for the immediate family, was located on the third floor. Here the most comfortable spot was the morning room, with a bearskin rug at one end and a tiger rug at the other. The mirror-paneled walls hid mysterious doors, which opened on a spring when the right spot was touched, revealing a fire hose, a storage closet with boxes of cigars, or an entire suite of rooms. Perhaps these doors were hidden out of whimsy, perhaps with an eye toward security.

The family of four had seventeen servants in residence, including a houseman, a waitress, two butlers, three cooks, and ten maids. For dish-ware, W.A. and Anna ordered from Chicago a nine-hundred-piece set of china, costing $100,000, or about $3 million today. It was a simple pattern, aside from the gold trim and Clark crest.

The room that Huguette described with the most fondness, years later, was the library, warmed by a fireplace from a sixteenth-century castle in Normandy, with armed knights standing guard as andirons. The mantel was carved with a scene of rural revelry, bringing to mind W.A.’s own origins, with a shepherdess, a bagpiper, and dancing men. The ceiling was of carved French mahogany from the 1500s, and the room contained three stained-glass windows freed from a thirteenth-century abbey in Belgium. Its thousands of volumes included Dickens and Conan Doyle, Poe and Thoreau, Ibsen and Twain.

A morning room in the Clark mansion was decorated with a tiger rug at the near end and a bear rug at the far end. The public areas downstairs were cavernous galleries and salons, while the suites upstairs were more warmly decorated for family living, though still featuring European furnishings and the finest Persian rugs.

Oh, but from France—their France—the library also held copies of letters of Marie Antoinette, a history of French illustration, and the fables: seventy-five volumes wrapped in red Levant morocco leather and gilt lettering, the works of Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian and his more famous predecessor Jean de La Fontaine. These were French versions of ancient stories still known the world over, such as “The Ant and the Grasshopper” and “The Miser Who Lost His Treasure,” along with lesser-known gems, “The Man with Two Mistresses” and “The Cricket.”

Huguette recalled nearly a century later how Andrée patiently read to her here, enjoying the fables and fairy tales of the France they had left behind. Of all the rooms in the mansion, the library was the one Huguette missed most of all.

. . .

Huguette once showed her nurses a photograph of “my father’s house” in a book of the great houses of New York. With evident pride she reminisced about how much fun she and her sister had had there. The architectural criticism in that book didn’t pierce her memories.

Critics have long been mixed in their opinion of the Clark castle: Some didn’t like it, and others thought it awful. It was called an abomination, a monstrosity, and “Clark’s Folly.” The Architectural Record said it would have been a fine home for showman P. T. Barnum. The horizontal grooves in the limestone suggested to some passersby that the building was wearing corduroy pants. Others were offended by the tower, so vulgar and bombastic.

It may be time for a reassessment of the Clark mansion. In his “Streetscapes” column in The New York Times in 2011, architectural historian Christopher Gray took the critics to task: “These opinions have been parroted many times but, upon contemplation, this is a pretty neat house. If Carrere & Hastings [architects of the New York Public Library] had designed it for an establishment client, its profligacy would certainly have been forgiven, perhaps lionized.”

It’s not clear, however, whether the true objection of critics was to the building or to the man it represented. Whatever one thought of the house, it was a perfect embodiment of W. A. Clark’s lifelong striving for opulence and recognition, his defiance of criticism, and his self-indulgence.

CHAPTER TWO

THE LOG CABIN

AN AMERICAN CHARACTER

WHEN THE SLIGHTLY BUILT MAN in the black frock coat and silk top hat stepped briskly down New York’s Fifth Avenue in the Easter Sunday parade of 1914, the gawkers saw his face and recognized him instantly. His bristly beard and mustache may have turned from auburn to gray, but at seventy-five years of age, he was the picture of sartorial eminence. The proud little man was accompanied by three discreet touches of male vanity: a gold watch chain hanging from his dapper white waistcoat, a polka-dotted silk cravat held tightly to his high collar by a pearl stickpin, and his thirty-six-year-old wife. The publicity-shy Anna walked in the parade by his side, wearing a flowered hat and an uncomfortable expression, perhaps attributable to the tiny steps enforced by her fashionable but thoroughly impractical hobble skirt from Paris.

Uncomfortable in public, Huguette’s mother, Anna, does not appear to be enjoying the Easter Parade on New York’s Fifth Avenue, which offered a chance for the public to gawk at the tycoons living on Millionaires’ Row. On Easter in April 1914, eleven-year-old Andrée walks in the parade, studying her fingernails while her mother gives her hand a tug. Seven-year-old Huguette stayed home.

There strode a man of unusual character, a symbol of two contradictory American archetypes.

W. A. Clark, businessman, was legendary, respected on Wall Street as a modern-day Midas. The epitome of frontier gumption, he was a triumphant mixture of civilizing education, self-reliance, and western pluck, living proof that in America the avenues to corporate wealth were open even to one born in a log cabin.

W. A. Clark, politician, was ridiculed on magazine covers as a payer of bribes, the epitome of backroom graft, and a crass mixture of ostentatious vanity, extravagance, and Washington plutocracy, living proof that in America the avenues to civic power were open only to those with the most greenbacks.

An indefatigable worker, W.A. carried on at a pace that today seems impossible, especially in an era when travel was by steamship and railroad, and communication by letter and telegram. During the first decade of the 1900s, for example, he maintained homes in Paris and Montana; built and furnished the most expensive house in New York City; constructed out of his own pocket a major railroad between Los Angeles harbor and Salt Lake City; subdivided and marketed lots for the city of Las Vegas; oversaw the operation of copper mines in several western states; ran streetcar and electric power companies in the West and a bronze foundry and copper wire factory in the East; grew sugar beets in California; published several newspapers; owned a bank with a good national reputation; was forced to resign from the U.S. Senate, then was reelected and served six more years; fought off a paternity suit filed by a young woman he had met at the Democratic National Convention; traveled through Europe collecting art; maintained good relations with his adult children; married a young wife and sired two daughters. All while in his sixties.

Though often chosen as a leader because of his intelligence, resolve, and deep pockets, he was not blessed with a magnetic disposition. W.A. was introverted and extremely private, a closemouthed man who acted as if he didn’t give a damn what people thought of him. If people didn’t like what he did, they were wrong. And yet he did give a damn about some things, including family, art, and social prominence. He was a seeker of public attention, not a great orator but a persistent one. He cheerfully took center stage to lead the singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at public events and didn’t limit himself to the familiar first stanza.

In the pocket of his cutaway coat, W.A. carried two grades of cigars, fine ones for himself and lesser ones to give away.

“TO BETTER MY CONDITION”

W. A. CLARK COULD HONESTLY SAY he rose from a log cabin to the most magnificent mansion on Fifth Avenue, a handy trajectory in America’s tradition of Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches stories. Yet W.A.’s beginnings were not so impoverished as he let on.

Will Clark, as W.A. was known as a boy, was indeed born in a four-room log cabin on January 8, 1839, but his grandfather owned a 172-acre farm in a remote corner of southwestern Pennsylvania called Dunbar Township. That’s southeast of Pittsburgh, about two miles outside the small city of Connellsville, then known for its iron furnaces. This area was becoming connected to a wider world. One of Will’s chores was to haul farm produce into town to sell to travelers who were leaving by flatboat on the Youghiogheny River, which led to the Monongahela, then the Ohio, and westward into the expanding nation.

Those were hard times. The nation had fallen into a seven-year economic depression beginning with the panic of 1837. It was not easy to see that the world was on the cusp of the second industrial revolution, when America would begin to take its place as a great power. In 1838, the year before W.A.’s birth, Samuel Morse demonstrated the first long-distance telegraph. A year after his birth, the first customer bought one of Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reapers for harvesting grain. The number of stars on the American flag had doubled from the original thirteen, reaching twenty-six with the addition of Arkansas in 1836 and Michigan in 1837. The people of Dunbar Township were buying their first books written by Americans. Will’s father had obtained an account of the westward journey fifty years earlier by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark (no relation).

“The scenes of my joyous childhood,” W.A. reminisced some seventy-five years later, were “outlined then by a very limited horizon. Nevertheless, I can recall ambitious speculations engendered in my mind when on winter evenings my father read the thrilling adventures of Lewis and Clark’s explorations. . . . This had the effect of strengthening my preconceived but ill-defined idea of adventure. And I recall telling my mother one day at luncheon hour, when I had returned from hoeing corn, and the weeds were really bad, that when old enough I would seek my fortune in the great West.”

During his later years, W.A. engaged the British School of Heraldry to trace his ancestry, with results he had the good humor to say were disappointing, for no famous people were found in his lineage. W.A.’s parents were of Scotch-Irish heritage,* a group that arrived in America with little in possessions aside from the Calvinist beliefs of their Presbyterian Church, pride in their work ethic, and the ability to distill a good grade of whiskey. The Clarks had come to Pennsylvania after the American Revolution from county Tyrone in the north of Ireland. W.A.’s father, John, was born in Dunbar in 1797, a few months after George Washington handed the presidency to John Adams, ensuring that America would not return to monarchy. W.A.’s mother, Mary Andrews Clark, was descended from Huguenots, French Protestants who emigrated from France to Scotland to escape religious persecution and then moved on to Ireland and America. W.A.’s red hair was inherited from his mother and shared by all his siblings.

A large family was necessary to work a farm, and John and Mary Andrews Clark had eleven children, eight of whom survived to adulthood. Their first child was a girl, Sarah Ann, born in 1837 and named for Mary’s mother. A little over a year later, on January 8, 1839, came William Andrews, or Will.† His sister Elizabeth, also known as Lib, described in a memoir the family’s tiring but joyous farm life:

What fun we had in winter too as well as summer! There were always the apples stored in the cellar and nuts we had gathered in the autumn. . . . I do not remember much about cooking by the fire as Mother had one of the first cooking stoves in the neighborhood. Most of the bread was baked in an outdoor oven. There never was anything in the world better than this bread with butter and homemade maple syrup or homemade apple butter! . . . We lived the outdoor life both winter and summer. . . . We had sleighing and coasting. We were often taken to school in a big sled with all the neighbors’ children.

Will’s schooling was limited to three months in the winter, because farmwork came first. The Clark children attended the public school, Cross Keys, in Dunbar. As the two oldest, Sarah and W.A. had an advantage over the younger children, going on at age fourteen to Laurel Hill Academy, a selective private school at the Presbyterian church in town. Such academies offered a meager college preparation course: a little algebra, basic Latin, a taste of history and literature, and public speaking.

The Clarks were not in that log cabin for long. With money Will’s father made mostly from harvesting trees, they moved into a larger wood-frame farmhouse on the property. When Will was about eleven, he helped his father build a handsome, two-story Federal-style brick residence, which stands today after more than 160 years.

John Clark passed on to his children great energy. He was proud of his fruit trees, prouder still of being a Presbyterian elder for forty years, and he was an advocate of hard work and fair dealing. Mary Andrews Clark gave her children boldness, ambition, and kindness. “Such good common sense,” sister Elizabeth said of their mother, “such beauty of body and soul, such refinement, very religious in a tolerant way, progressive with a good sense of fun.”

In 1856, at age sixty-two, perhaps a dubious age to start a new venture, John sold the Pennsylvania farm and moved his family west, traveling more than seven hundred miles by rail, steamboat, and stagecoach to the deep, loamy soil of Iowa. Seventeen-year-old Will drove a team of horses by himself the full distance ahead of the family.*