Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

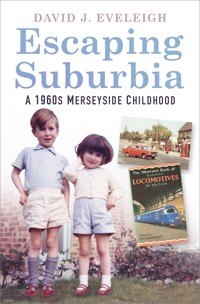

Born into the gap between the eras of austerity and boom, David grew up in Merseyside amid an inexorable tide of progress, developing a fascination with the past. With a vivid eye for detail and boundless childhood curiosity for everything from steam trains to 'My Old Man's a Dustman', his account documents the uneasy relationship between worlds old and new. Featuring unique photographs and authoritative observations on architecture, social and local history based on forty years' work in museums and heritage conservation, Escaping Suburbia offers a different view of the 'swinging' sixties.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© David J. Eveleigh, 2019

The right of David J. Eveleigh to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9341 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

PART ONE: 1955–59

1 Introductions

2 Inside 178

3 Suburban Spread

4 Living in 1 Orchard Way

PART TWO: 1960–66

5 Starting School

6 Train Journeys

7 Evenings and Weekends

8 The Facts of Life

PART THREE: 1966–69

9 Grammar School

10 ‘Progress’

PART FOUR: IRELAND

11 The Emerald Isle

12 The Secret Garden

13 Broken Glass

Postscript

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

When I began this project I asked Nick Wright, with whom I had worked on two previous publications, if he could read through my draft text as it evolved, and serve as my mentor. Nick performed this task with brutal honesty: it was what I wanted. ‘No one is interested in you,’ he said, and I have no doubt he is right. I had to make sure that my account was not a load of senseless drivel that would appeal to no one – except me – so through the eighteen months of writing and corrections, Nick performed the role of mentor superbly. I am indebted to him. I would also like to thank Sir Neil Cossons, who read and commented on the text and provided the foreword. I also received help from many other quarters. Thus, I am grateful to my mother for checking my recollections of certain events and things. Bernard Thornley, my history teacher from Wirral Grammar School, read through the chapter on my time at the school and provided some very useful background information as well as saving me from a few factual errors. Donal Hickey from Killarney, formerly a journalist with the Cork Examiner, made some invaluable observations on the section on Ireland. Thanks are also due to Barbara James, granddaughter of Catherine Connor, and to Ann Evans, née Chadwick, who replied to requests for information. I must also thank some old friends and former colleagues who read through drafts of the book. So, I extend my warmest thanks to Richard Wynne Davies, Alison Farrar, John Freeman, Peter Hofford, Adrian Targett, Mel Weatherley and also Dave Ring – who is normally too busy making tea and playing golf to read anything – for their invaluable feedback. Thanks are due to National Museums Liverpool and Wirral Archives for their assistance, and I am also grateful to the Williamson Art Gallery & Museum, Birkenhead, for permission to include the two paintings by Harold Hopps of Kings Farm and Higher Bebington Mill; to Birkenhead Central Library for permission to use the illustrations on pages 20, 135, 136, 140 and 149 and to Abbey Garrad and her colleague, Tom, who ran the extra mile in making the library’s photograph archive accessible. I am also grateful to C.M. Whitehouse for permission to use his photograph of locomotive 42587 on page 138. I am also very grateful to The History Press for turning my typescript into a book and to the team who worked on the project with remarkable speed and efficiency. Finally, I need to thank my partner, Geraldine, for her patience: from the beginning she has had to put up with me talking endlessly of this project.

D.J.E.31 March 2019

Foreword

There is a frequently quoted saying: ‘If you can remember the sixties, you weren’t really there’, which, despite its supposed origins in California, might have applied equally to Liverpool, then riding high on the reflected glory of The Beatles and all they represented. These were the years when the American beat poet Allen Ginsberg saw Liverpool as ‘The centre of the consciousness of the human universe’.

This book is the antithesis of all those sixties clichés. Here, David Eveleigh’s acutely vivid observations and the reflections that emerge from them paint a very different picture: of a boyhood characterised by its essential ordinariness, set out with an engaging kindness and clarity. It is his ability to portray the everyday that makes this such a refreshing read. His is a detached yet personal portrayal of his surroundings during his boyhood years, about his home and his home life in Bebington on the Wirral peninsula in Cheshire – unquestionably not Liverpool but, crucially, Merseyside. A childhood in a three-bed 1930s semi, with an open coal fire burning Sunbright Number 2 and a table lamp made from a Mateus rosé wine bottle, reflected a familiarity invisible to most, but it is seen here as a prelude to change and all that went with emerging sixties affluence and the cupidity that was part of it. Yet his views are not about the acquisition of material things – on the contrary – but of the inescapability of the events that take place around him. Here lies the strength of this book.

He notes, and to an extent revels in, the Victorian buildings of his surroundings – if only because they are leftovers from another age, unfashionable and despised, condemned to disappear in the face of acres of new housing. Yet the pull of aspiration and the desire for the new takes his own family and him with it into this new world, to a new house, new household goods and, crucially, a new place that is detached. That his house no longer touched its neighbour, however small the gap between them, signalled a difference that mattered long before the word affluence had been discovered. His was a loving middle class family, offering a stable boyhood and allowing David the space to reflect in comfort and with quiet surprise.

Nor are these nostalgic sentiments (although there are painful regrets as steam railway locomotives disappear), more a quiet non-judgmental succession of observations on all that went on about him. He reflects too on summer holidays: by train to North Wales, later to Ireland by plane and then in the family car, by boat to Dublin and the long drive down to the south west. These holidays were spent in hotels, again a sign of a new and real prosperity, a defining feature of sixties change. Here, in Skibbereen, on a flickering black and white television, he saw man for the first time put his foot on the moon. David Eveleigh’s sixties boyhood ended with that holiday.

Neil Cossons

Introduction

It is probably true to say that I have been writing this book all my life. At least in my head and at least from the time we left my grandparents’ house, my first home, in 1959. From then onwards I stored up memories of my childhood, kept diaries for some years and held on to other things, mementos of my childhood including books, toys and some of my drawings. But it was only in 2017 that I started writing. We were on holiday in Greece on the wonderfully quiet and peaceful island of Alonissos. I bought an exercise book and black biro in the newsagents in the main town, Patitiri, and with a clear head – away from the pressures of work and everyday life – and with the blue Aegean in front of me, I laid down the first 6,000 words longhand. Upon returning home I typed up my manuscript, editing and refining the text as I went, and soon completed part one, whilst at the same time sketching out a structure for the rest.

This obviously begged questions as to the purpose of the book. My shorthand for the project when talking to friends and family was my ‘memoirs’. But I quickly realised that the book should not constitute a blow-by-blow account of my childhood; neither was I attempting to write a comprehensive social and cultural history of the 1960s. That has been done superbly by others. The finished book lies somewhere between the two. It is an account of one very ordinary boy growing up in the ’60s, perhaps with a larger than average dose of nostalgic sentiment and interest in the past, and forms a compendium of personal experiences and observations. Some of these are trivial, personal and obvious, but they are very likely experiences shared by, or at least very similar to, those of other children from this time. The recollections of how my parents furnished their new house in 1959, how I started school, watched TV and underwent life at secondary school – in my case a state grammar school – describe experiences that I expect many readers will identify with and will perhaps trigger recollections of their own childhood.

The book also contains my memories of how I reacted to the wider world. As a young child I had no idea that I was born on the cusp between two post-war eras: austerity and boom. Rationing had ended only in 1954, the year before I was born, and had effectively closed the period of austerity, of make do and mend, utility and frugality, but within three or four years the floodgates of the boom years opened. Utility was replaced by rampant consumerism, an attitude that through hire purchase agreements people could realise their dreams and aspirations in an instant: of owning an electric cooker, a fridge or even a car. In 1957, the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, was able to say that most people had never had it so good. This was the world I was born into. My parents’ new home of 1959, which I describe in detail as I remember it, was typical of the time. Yet the Second World War still hung heavily over our lives into the 1960s. Neighbours, parents of school friends and school teachers had served in the armed forces between 1939 and 1945, although to me as a child the war seemed a long way off. Such is the perception of time for the young when a year can seem like an epoch and the previous decade the far and distant past.

The first event that I can recall from the wider world was the wedding of Princess Margaret to Anthony Armstrong-Jones in 1960. This also happened to be the first year that I knew by date, and until I started writing I had not appreciated that this wedding was the first national event I was aware of, but so it was. Reading a draft of part of the book, a friend said to me: you mention the Cold War, but you don’t mention the Cuban Missile Crisis. Well that is quite simply because I remember the Cold War; it was part of the framework or background to everyday life in my first decade, but I don’t remember that particular crisis. I heard the name Khrushchev on the radio a lot around this time but I’m sure that the first time I heard of President Kennedy was the day he was assassinated. The book is selective. As I wrote, many of my childhood memories, including personal adventures or misadventures and recollections of current affairs, fell to the ‘cutting room floor’. I do not attempt to comment on every news story or television programme I remember. So, recollections of the Vietnam War, the unfolding crisis in Biafra and at home, the conviction of the Kray Brothers and the Moors Murderers do not fit my narrative, even though I can recall all these news stories, mostly courtesy of the early evening BBC television news. There are also many TV programmes that I liked and remember, such as Dr Finlay’s Casebook,Z Cars and The Man From U.N.C.L.E., which are not featured in my story. To have included everything would have resulted in a long and unreadable mush of memories and no clear story. I talk of things that made a big impression on me, like the first time I saw Doctor Who, heard a Beatles song or watched the Apollo space missions on TV. It is a random list, but it is authentic.

The 1960s was a fast-moving decade. It has been described as a period of tumultuous change and the most transformative decade of modern times. Certainly, for me as a young teenager in 1969, the year 1960 seemed like a distant past. This may be in part the perspective of childhood when time passes more slowly, but the pace of change in many spheres of life was quite striking. Whilst some look back with affection to the period – it was retrospectively named the ‘Swinging Sixties’ – and talk of the sense of optimism they felt at the time, I found some of the progress painful and mourned the passing of certain things. I reacted against the modern suburbia I was brought up in. In many ways I should be grateful for growing up in a clean, comfortable and safe environment, but I couldn’t help finding it boring and unconsciously I was searching for a more interesting world: the countryside, Victorian Birkenhead, and finally as a child I found a world I loved on holiday in Ireland. But the last holiday there in 1969 when I was 14 unexpectedly brought my childhood to a close.

My instinct when young was to explore the past through reading, drawing – even a bit of fieldwork – but also by talking to older people I encountered, many of whom had been born before 1900; so, as I wrote, a sub-theme of the book emerged of how in the 1960s, Victorian ways of life and Victorian objects remained a part of everyday life in opposition sometimes to the bright, new, shiny 1960s. But it was slipping away rapidly, and we just caught the tail end of the Victorian world before it was largely snuffed out by the inexorable march of progress. I bring to these pages some of the people I met – some of them Victorian, some nameless, but snapshots of people I encountered who, in one way or another represented a way of life that was rapidly disappearing: people like Harry Henshaw, Bert Richards (the Great Western Railway engine driver) and Catherine Connolly in Rock Ferry who lived over a quarter of her long life in Victorian England. I am fascinated by old things (academics talk of ‘material culture’) and heritage in situ, but I have increasingly come to value the role of ordinary people and their individual stories in making sense of the past and bringing it to life in a way that is colourful and intimate. These people would otherwise slip out of history but reference to their lives not only preserves a little of them but puts flesh on more academic histories and can also bring inanimate objects to life.

But this is chiefly my story of that decade: of one ordinary boy growing up in Merseyside suburbia in the 1960s. Perhaps it may fill a gap in the literature of the decade, recording some aspects, such as life at home, at school and on holiday, and offer a different perspective to conventional accounts of the time. This, I believe, is the chief purpose of this book.

Part One:

1955–59

1

Introductions

I have in front of me a copy of my certificate of birth. In black ink it states that I was born in Birkenhead on 20 June 1955. Of course, I know this. It was my mother who added that it was early on a Monday morning (about 5.30 a.m.) when I arrived in the world. The precise location was ‘Annandale’, a private nursing home in Storeton Road in Prenton, Wirral, Cheshire. Apparently, it was a sunny morning, windows were open and bees hummed around the cut flowers given to my mother. Storeton Road is not far from Higher Bebington, where my parents then lived. My father, Sydney Eveleigh, was from Yorkshire, and had served for several years as an engineer with the Blue Funnel Line. They had met two years earlier at the Tower Ballroom in New Brighton, and married in May 1954. I was the first born; two sisters were to follow.

The family home was ‘178’, a 1930s semi on Higher Bebington Road that my mother’s parents had purchased new in 1934. My mother, Barbara Wynne Jenkins, was the only daughter of Fred and Margaret Jenkins. Fred – and that was the sum total of his forename – was also a native of Birkenhead but had spent most of his early years in Liverpool. There he had trained as an architect at the Liverpool School of Architecture at the university. His wife, my maternal grandmother, was Margaret Coucil; she came from a respectable working-class family who lived in a council house in Knotty Ash, Liverpool. Fred and Margaret had married at St John’s the Evangelist, Knotty Ash, in October 1928 and their daughter was born in Knotty Ash in August 1931. The jam butty mines of Knotty Ash, ‘diddymen’ and tickling sticks all lay in the future, but perhaps Fred and Margaret had ordered their coal from one ‘Dodd, Coal Merchant’, as the father of the entertainer Ken Dodd was a coal merchant in a big way in that part of Liverpool.

The decision to relocate across the Mersey to Wirral was not untypical at this time. With excellent links by ferry, underground electric trains and, after July 1934, by road through the Mersey Tunnel, Wirral was rapidly establishing itself as a popular dormitory area for working families in Liverpool. Facing Liverpool, the Wirral peninsula was predominantly industrial and urban in character – all the way from Birkenhead Docks for about 4 or 5 miles upriver to the entrance locks of the Manchester Ship Canal at Eastham. But away from the Mersey, it was a different world: a place of ridges and outcrops of sandstone, gorse and pine trees, patches of woodland and pretty winding roads linking its villages, hamlets and farmsteads. It contained some old sandstone churches with broach spires – which are easier to admire than explain – and also several windmills. The Wirral was ideal windmill country, windy and exposed, and in the 1930s a handful of these windmills still survived. Bidston Mill, which can be seen from Liverpool, was the first windmill to be preserved in Britain, in 1894. The head of Wirral faces out to Liverpool Bay. Here is true coastline containing several small seaside towns like New Brighton, Hoylake and West Kirby, which expanded after the opening of the Wirral Railway in the late nineteenth century.

Bidston Mill, a typical Wirral tower windmill. It dates from the early 1800s and consists of a three-storey brick tower. It worked until 1875, replacing an earlier timber post mill destroyed by fire in 1791. From a postcard used in 1924.

Cumbrous round arched doorways, pebbledash and stained glass in the windows: typical 1930s semis in Larchwood Drive off Town Lane, Higher Bebington.

So, Wirral was ripe for development and this was no isolated phenomenon. From the late 1920s and through the ’30s, the development of new suburban estates, typically on the edges of towns and cities, was rapidly accelerating. The building of local authority estates had begun shortly after the end of the First World War to ease a chronic national housing shortage but by 1939 they had been outnumbered roughly two to one by privately built houses aimed at a new class of property owners. It was in these inter-war years that Middlesex, for example, largely succumbed to concrete, bricks and Portland cement (except for some generous grass verges and golf courses) and when several parts of Wirral acquired a distinctly suburban character.

Wirral suburbia was no different from suburbia anywhere. Indeed, one particular feature of 1930s housing is that it really did not matter where you were: it all looked pretty much the same – from Sidcup in Kent, most of Middlesex, Westbury on Trym in Bristol to extensive developments in Birmingham and Liverpool – and elsewhere. Whilst there were a few detached houses, and bungalows were quite popular, the greater part of this new wave of housing consisted of the three-bed semi, typically rendered in grey or brown pebbledash with cumbrous round arch open porches over and around the front door. They were laid out in avenues, ways and lanes, and the odd boulevard, but never or rarely was the name ‘street’ applied. Whilst ribbon development out of town of semis on busy roads was common, the typical development followed the garden suburb ideal that had emerged in the 1890s. The idea of a street conjured up a way of life that was the antithesis of the new estates, a world of dense town housing, some of it with backyard WCs, trams rattling by, smoky brick and little greenery. Life in the 1930s brought the opportunity for some of ‘living the dream’, of acquiring a home in a spaciously laid-out suburb with open country most likely nearby, but with the assurance that the new home had gas (for cooking), electricity (for lighting, the wireless set and the laundry iron), good drains, a bathroom and an indoor WC.

Such was 178 Higher Bebington Road, and when my maternal grandparents moved in there with their little infant daughter in February 1934, they were very likely home owners for the very first time. And 178 was close to open countryside. Higher Bebington Road was a 1930s development that ran downhill through former heathland towards Lower Bebington. The two settlements of Lower and Higher Bebington are about a mile apart and connected by a main road that runs all the way from New Ferry to Birkenhead, changing name several times on its route, although on its passage through Higher Bebington we simply referred to it as the ‘Main Road’.

Christ Church, Kings Road, Higher Bebington. Designed by Walter Scott (1811-75) it was consecrated on 24 December 1859. The tower and spire were added in 1885. The Vicarage – also built of Storeton stone – is on the left.

Lower Bebington was – and remains – the more important of the two, with an attractive parish church, St Andrew’s – a sandstone church and one of those Wirral churches with a broach spire – municipal offices in Mayor Hall, and a railway station on the main line between Birkenhead and Chester. Between the railway and the banks of the Mersey lie New Ferry and Port Sunlight. Brunel’s famous steam ship, the Great Eastern, was broken up on the beach at New Ferry in 1889–90 and it is claimed that it is still possible to find slivers of wrought iron from the hull in the sands of the beach. Port Sunlight, a model industrial village, was begun in 1889 by William Hesketh Lever (1851–1925) to provide homes for the workforce of his famous soap works. With its pretty cottages recalling vernacular building traditions, formal gardens and imposing art gallery, Port Sunlight is like nothing else on Wirral – except perhaps for Thornton Hough, a rural estate village of similar architecture that Lever also laid out.

Higher Bebington lies about a mile or so up this main road past the new grammar school, which had opened in September 1931 in what was then virtually open countryside. It was a village of small farms, quarries and stone cottages chiefly occupied by quarry workers and farm labourers. There was also a scattering of large red brick houses standing in their own grounds and typically screened from the road by tall trees: these were usually occupied by wealthy merchants and professional people who worked in Liverpool. On Kings Road, part of the main road heading towards Birkenhead, a parish church had been added in the late 1850s and, like so many Victorian churches and church restorations of the time, was finished in a textbook version of thirteenth-century ecclesiastical architecture. It was built of the hard, creamy white Storeton sandstone that had been quarried in the village since Roman times. Close up, chisel marks on the blocks used for the walls and buttresses can be clearly seen. They give the exterior walls a robust finish – like the ‘rusticated’ stonework of classical architecture – contrasting with the smoothly finished stonework around the windows and doors: these chisel marks stand as a silent and unwritten memorial to the forgotten local men who hewed each building block out of the quarried stone …

Higher Bebington windmill and outbuildings in the 1960s.

The centre of Higher Bebington was Village Road, which climbed from the main road (Teehey Lane) towards the wooded Storeton Ridge. Village Road contained a rather handsome Arts and Crafts style village hall – the Victoria Hall of 1897 – a straggle of stone cottages, some Victorian red brick shops and houses, three public houses (the Royal Oak, which carried a date stone of 1739, and then further up the hill, the George Hotel and the Traveller’s Rest). Near the top end of the village, at the end of Mill Brow, there was an early nineteenth-century windmill and just beyond the mill, a large and deep quarry that remained a going concern until the late 1950s. The windmill had ceased working around 1901 and by 1934 it presented a forlorn spectacle: its sails and external timber gallery had been removed and its cap had blown off in a storm the previous year, but the red brick tower, still and silent, remained a familiar landmark visible on the approach to the village, especially from Lower Bebington, and provided a focal point and some character to this otherwise unremarkable village.

The top end of Village Road ended at a crossroads where it met Mount Road. The Traveller’s Rest stood on one corner and opposite was a small corner shop. Across the road were Storeton Woods, which contained several disused quarries of the same Storeton sandstone hidden amongst the scots pine, birch and oak. Mount Road followed the ridge and in the Birkenhead direction crossed into Prenton, where it became Storeton Road. And that takes us back to my first few days in Annandale nursing home …

2

Inside 178

A terse entry in my grandfather’s diary for Saturday, 2 July 1955, records, ‘Barbara came home from Annandale. Meaney used his car.’ Edward (Ted) Meaney lived next door with his wife, Gwen. Fred had also recorded the delivery of a pram and cot in readiness on the two previous days. Margaret, my grandmother, was no longer there. She had died suddenly of a stroke in September 1953. For Monday, 18 July, my grandfather wrote ‘Baby 4 weeks old today’. But he had not long to live. Fred had terminal cancer and made his last diary entry on 30 August. He died just a few days later.

We were to leave 178 just before my fourth birthday in 1959. I was happy there. I recall a tranquil and comfortable home and when it came to leave, I experienced nostalgic regret and sadness for the first time. The houses in Higher Bebington Road were built by Ben Davies, who was responsible for several other developments in the area. The interior that I distantly recall was fitted out and furnished largely as my grandparents had arranged it in the 1930s and ’40s.

Oak panelling in the hall and stained glass at the front were standard but my architect grandfather specified that these were omitted. Of the houses built by Davies in Higher Bebington Road, only 178 lacked these features, which Fred doubtless regarded as pastiche. The interior décor was different from the neighbouring houses, with furnishings, pictures and ornaments that reflected my grandfather’s interest in art and his circle of artist and craftsmen friends in Liverpool.

Fred was a member of the Sandon Studios Society, a club of architects, artists and sculptors, founded in 1905, that met in the Bluecoat Chambers, an early Georgian building in the centre of the city. One of his close friends was the well-known Liverpool sculptor, Herbert Tyson Smith (1883–1972): Fred owned several pieces by Herbert, including a beautiful small green bronze figure of a woman. Another of his friends was the photographer Edward Chambré Hardman (1898–1988), whose house and studio in Rodney Street is now owned by the National Trust. Hanging on the wall were original drawings and paintings by artists he knew, including an oil on canvas portrait of Margaret painted by another Sandon Studios member, the painter Henry Carr (c. 1872–1937). There were Japanese prints – a fine engraving of an early-Victorian steam ship, the Archimedes, which I remember was in the hall – and there was also a striking drawing of a nude by W.L. Stevenson, who went on to become the principal of the Liverpool School of Art; he was there when John Lennon was a (troublesome) student at the college in the late 1950s. As a young child I saw this drawing, which resembles the art of Eric Gill, as an indecipherable mass of scribbled lines.

Fred Jenkins (centre) with Harold Hinchcliffe Davies, a well-known Liverpool architect, and his wife Nora, photographed by Edward Chambré Hardman at a café in Avignon between 10-13 June 1926.

The interior colours were muted. There was a lot of cream and green and the curtains in the front room consisted of floral prints. The dining room was papered in a light-cream textured wallpaper. The carpet was a mid-green, plain apart from a subtle twirl in the weave; the furniture included a mid-eighteenth-century panelled oak chest and a large, tall and dark oak bookcase – a wedding present to Fred and Margaret – which my mother later gave to the Salvation Army. There was also a large radio or wireless set – this was a Pye model, pre-war, with a cut out rising sun design over the speaker, a trademark design feature of the company. I also recall that there was an old-fashioned wind-up gramophone in the front room. Upstairs there was a separate bathroom and WC with a wooden seat, but the two rooms I remember most clearly are the morning room and the kitchen, doubtless because these were the rooms of everyday living. The morning room led off the hall and looked onto the side of the house and had an open tiled fireplace: the fire was lit regularly (with Co-op or Bryant & May’s Pilot matches). The room was furnished with a pine kitchen table with a drawer at one end and three Windsor chairs. One of the few changes made by my parents in the home in the late 1950s was the addition of a television set, which was purchased around 1958. Whilst I have no recollection of the arrival of the TV, neither do I ever remember life without television, and this was to be another major influence on me – as it doubtless was for many children – through the following decade. The morning room led through into the kitchen, which occupied a single-storey extension at the rear of the house. This created a more spacious ground floor plan than some inter-war semis, which instead had a small ‘kitchenette’ squeezed into the basic rectangular house plan. Our kitchen was quarry tiled and fitted with a white fireclay sink and a scrubbed wooden drainboard. The back door led to the side of the house and another door opened into a small walk-in pantry cupboard.

The washing machine was a Hotpoint with a wringer that swung out over the drainboard on washing day. Cooking was done over a New World gas cooker. By 1939 roughly 90 per cent of British households cooked by gas and this was a very typical cooker of that period. It stood on short legs and was finished in a mottled grey and white enamel. As an infant, I had a near-fatal attraction to the row of brass keys that controlled the burners. These were just above the oven door and within easy reach of an infant. There was no safety ‘push in and turn’ device: turning the key simply opened the supply of the deadly town gas. And one morning, with my mother out of the room, that is precisely what I did. Fortunately, my mother smelt the gas from upstairs and rushed down to find me ‘grovelling’ on the brown mat by the back door: this, I can remember. The doctor was called and, apparently, I was walked around the garden to clear my lungs.

Higher Bebington Road photographed probably shortly after completion in c. 1934; 178 was lower down on the left obscured in this view by the trees across the road.

A photograph of the dining room at 178 Higher Bebington Road looking towards the French windows, taken by Fred Jenkins in 1937.

The back kitchen door opened onto a concrete path that ran down the side of the house to the back garden: 178 was the left-hand house of the pair. There was a brick and concrete air raid shelter here that my grandfather had built in time for the Blitz. Of course, I knew nothing then of the Second World War and had no comprehension that the shelter was used by the family and some of the neighbours, including Gwen Meany – and her fur coat, apparently – in a time of great fear and stress during the height of the Blitz. Later, as an older child, I was told that my grandfather had a collection of firearms and, worried that in wartime they might have attracted the attention of the authorities, he buried them, wrapped in tarpaulin, in the concrete base of the shelter. I have often wondered if they were ever discovered …

Early memories are fragmentary and follow no chronology. I have a curious first-hand recollection of trying to steady myself by clutching the green stalks of plants in an attempt to stay upright but finding they were not strong enough to take my weight. The story I was later told was that on a fine spring day I had been put outside in my pram – a large black ‘Silver Cross’ vehicle – and had rocked it so vigorously that it upturned and I tumbled out, held precariously at about ground level by the pram straps. And so, was I found, dangling in a bed of bluebells, under an evergreen tree. I know this is a first-hand memory even though I must have been just ten months old. Another random memory is being taken to post a letter in Ted Meaney’s car – the same one I was first brought home in. I clearly remember sitting in the front of the car for the short drive down the road and seeing the red post box ahead. When we stopped, I was lifted up to post the letter. Generally, there were few cars in the road. Most were black, and I remember the occasional passing of a rag and bone man with a horse and cart.

Without taking much notice, I was joined by a sister, Janet, who was born on 19 May 1957, also in Birkenhead. She was given Wynne as a middle name, a name shared by my mother and a great aunt, Lilias, one of Fred’s sisters. It was a family name and a memory of Welsh ancestry. A pleasant recollection from about 1957 or 1958 is of sitting on the edge of the pram with Janet asleep under the covers as my mother took us with her, shopping in Lower Bebington. Then in the spring of 1959, I recall my first sequence of events. I was sent to stay with one of my mother’s friends, a young woman called Ann Chadwick, at her family home, 57 Halkyn Street in Flint, a large late Victorian house with a long narrow garden near a brick-built chapel. Her father was one-time mayor of the town. Ann was unswervingly kind and lovely: she would shine a torch around the bedroom if I was frightened of the dark, provide me with limitless jugs of water so I could make any number of mud pies in her garden, and take me with her when she went shopping in Chester by train. Then one warm and sunny day when I was playing on my own in her garden, she suddenly announced it was time for me to return home. Ann used her brother’s car – a black Vauxhall – to take me home and I sat in the front passenger seat as we drove to Bebington in fine weather along country roads: I remember clearly the white iron fences bordering the fields, which are often seen in rural Cheshire. Immediately upon arriving home, I was led upstairs and holding my slightly grubby hands tight at my side, there I saw – fast asleep – a new sister, in my bed! Helen had been born at home a few days earlier on 11 May.

I also knew we were to leave 178 and preparations must have been at an advanced state by then, for on 13 June 1959 we relocated to a brand-new detached house about half a mile further up the hill in Higher Bebington. But I was not present to witness this momentous event. Doubtless to lessen my parents’ lot, I was packed off to stay for a few days, while the move took place, with an older couple my mother knew – the Websters, who lived in Lower Bebington. I did not particularly enjoy this second short stay. I vividly remember on a fine day, walking around the circular ornamental path in their back garden singing a tuneless song about making my way home. The Websters were sitting in the sun and peevishly asked me if I wanted to go home. I was taken aback and made my apologies. I had not intended to cause offence and denied I wanted to leave, when this was almost certainly the case.

Detail of a 25 inch to the mile Ordnance Survey Map of Higher Bebington, 1874. North is top. Orchard Way later occupied most of field 78. The sycamore trees behind Elm House are marked. Well Lane is bounded by Claremont and Elm House. The windmill is seen centre. Storeton Woods are just visible left of Mount Road whilst the Higher Bebington Freestone Quarries are near the National School. The Storeton Tramway passes under Mount Road. Mill Road School was later built on the allotment gardens, replacing the National School.