9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

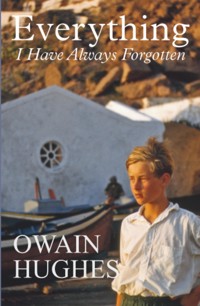

Everything I Have Always Forgotten is the story of Owain Hughes' childhood in the 40s and 50s. He spent it in boarding schools and in his family's large (but electricity-free) house, on the banks and waters of the Dwyryd estuary, and above all walking in the mountains. The landscape of North Wales - with Snowdonia in the near distance - dominated Owain's existence, and his stories of sailing, riding and walking culminate in the five-day hike through Snowdonia by the eleven-year-old Owain and a school friend.The trip ended with them storm- bound for several weeks on the Holy Island of Bardsey off the coast of North Wales, without any means of communication with his family.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

OWAIN HUGHES

Everything

I Have Always Forgotten

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd.

57 Nolton Street, Bridgend,Wales, CF31 3AE

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooks

Twitter: @SerenBooks

The right of Owain Hughes to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

© Copyright Owain Hughes, 2013

ISBN 978-1-78172-099-8

Mobi 978-1-78172-100-1

Epub 978-1-78172-101-8

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council.

Printed by

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART I – THE BEGINNING

I

Leftovers of the 1920s

II

The First Winters

III

Home

IV

The House

V

Fireside Tales

VI

Postwar Survival / Babysitters

VII

Granny Cadogan

VIII

Nice Sicilian Murderer

IX

Berserk Jeep Hits London

X

Dylan

XI

Back to W.W.II

XII

Haven with a Spy

XIII

Rain, Sex, School

XIV

Misty Mountain

XV

Mountains and Guns

XVI

The Sailing Bug

XVII

Now Hooked on Sailing

XVIII

Pony Trekking

XIX

A Shepherd Swims

XX

My Very Own Trip

XXI

Courting Death on Cliffs

PART II – THE JOURNEY

XXII

The Flying Dutchman

XXIII

The Journey Begins

XXIV

The Journey Blessed

XXV

Into the Wild

XXVI

Merlin and Other Wizards

XXVII

Passage To Bardsey

XXVIII

Storm Bound

XXIX

Home At Last

Afterword

INTRODUCTION

As Mother lay dying, crippled by pain and humiliated by incapacity, I asked her if she was worried about me when I walked to Bardsey Island with my school friend Alan, at the age of eleven. She closed her eyes and scrunched up her deeply lined face with concentrated thought. After a while, without opening her eyes, she said only: “I forget” and her face relaxed again, relieved not to have to try to remember any more. I had waited too long to ask. The smell of aseptic old people’s home flooded back over my old memories of young health and strength, hiking in those clean mountains, now that I was forty…

Rarely do I talk of, or seek to remember, my childhood. Those who knew my circumstances say that it must have been ‘idyllic’, but childhood is often pain and simple sadness. It is lost, as if shrouded in the clouds that hang about the summits of mountains. From time to time, those clouds may be rent with a tear, opening up a view of the landscape, oh so far, far below – or showing in this simile, just for one moment in time, a brief historical vignette. These are some such brief glimpses through the clouds that I shall try to show you, piece by piece. Perhaps they are not special, but they are mine. Though some of what I relate derives from the tales of others, even some of my own, I confess that many may be apocryphal – but what would be the interest in two people telling the same story? It would be mere repetition worthy of a parrot or a tape-recorder, not a large and creative family.

Bardsey was my first self-motivated trip in 1955. Of course, by then I had travelled by train alone to school, starting at the age of seven, but that was not my choice. Neither was the expedition which my youngest sister and I undertook on horseback. The true revelation came when I decided where I wanted to go. When I walked to Bardsey, financing the trip myself… that was the real beginning of my life. That led to 1963 (aged nineteen), when I walked and hitchhiked to the south of Iran, then across the Sahara, from Mauritania to Egypt. These were true expressions of choice. As politics have panned out, many of those trips could hardly be made today, as I made them then: with a backpack, a sleeping bag, a notebook and phrasebooks of Farsi, Arabic, Turkish and Greek. The trip to Bardsey was the last time I ever brought a tent. A tent is too great an advertisement of where one is sleeping. Of course, being eleven years old, Alan and I were insouciant, totally unaware of risk from other human beings. We were accustomed to the kindness and sharing that had sprung from the common suffering of the appalling Second World War. The war in which everyone was defeated except the Americans. Later I was to learn that better by far is to creep into the shelter of a bridge or unused drainage pipe after dark and there to simply slip into the sleeping bag, to rest unbeknownst to the world in general and the local populace in particular. Oh yes, Alan and I certainly respected cliffs, tides and heavy storms at altitude or at sea – but ‘Evil-Doers’ were not in our lexicon, as they surely would be today.

As for training my Parents to allow me such liberty, it seemed to come to them quite naturally and, besides, I was the fifth child so I have my older siblings to thank for laying the groundwork, for raising our Parents so well and so liberally…

Before I could walk and climb, I had to crawl, so I quote the bard, Mr Thomas: “Let us begin at the beginning.”

This is a tale of a child’s life before the concept of ‘Helicopter Parents’ became so pervasive: those parents who continually hover over their offspring, watching that no harm could possibly befall their precious babies, their fledglings.

Before the Padded, Insulated, Protected – the ‘Bubble-Wrapped’ World came into existence. I was raised under Father’s principle of: “plenty of benign neglect”. Indeed, he himself had been raised by his widowed mother and spinster aunts and became obsessed with their cloying, over-protective care. He essentially left home at the age of sixteen.

So, I was always fed, had a roof over my head, was somewhat clothed, sent to private schools and my reports were read and remarked upon. With any more supervision than that, exactly what encourages a child to develop?

Recently, I heard that a friend’s young teenage daughter had disappeared after a quarrel with her parents over her privacy from her three younger brothers. Desperate after searching for three hours, they called their neighbours – one of whom was the village mayor. It was a cold, drizzling, winter’s day in this southern French village and night would soon be coming on. Their friend and neighbour, the mayor, told them that after three hours’ absence, he was obliged by law to call in the police. After dark, they would have to call in a helicopter. Gendarmes and CRS officers, twenty vehicles full, combed the surrounding area until finally a tracking dog was brought from 100 kilometres away. The dog immediately found the child cowering under a bush in her parents’ very garden.

As a toddler, I wore a little harness with round bells on it, so that Mother knew just where I was as I tinkled about like a little goat… oh the joy of cantering off alone amongst the gorse bushes, out of sight of authority! Mother never held the reins (I probably pulled at them too much, like an untrained dog on a leash), yet I was tagged as surely as if I wore a GPS microchip. Once I grew out of that harness, I could disappear in a rage or a mood and no one would notice I was gone. I would come home when I was hungry, cold and wet. True Refugees do not have the luxury of sulking.

So begins the unfolding of my life, like a snail, spiralling out and out and suddenly on and on into the great unknown to be discovered. Other places, other times – we start at point zero, and adventure, eventually, to the uttermost corners of the earth, but it is a spiralling thing that develops and finally spins out on its own – this is Life.

PART 1

THE BEGINNING

I

LEFTOVERS OF THE 1920s

Oh, that delicious first moment of six-year-old consciousness in the morning: when the bedroom wall is dappled by limpid sunlight, so clear and fresh, filtering through tree leaves that shiver slightly in the early morning breeze – their blurred shadows flickering and dancing upon the wallpaper by my bed. That delicious, warm first moment when there is a tremor in one’s lower self and, since Mother is not there to say: “No wigwig”, one can indeed indulge in secret, delicious, forbidden wigwig. It could have gone on for ever and ever, but…

I heard the growl of a lorry outside and, even forgetting wigwig, sat up and looked out of the window. There was an old lorry in the garden outside, towing away Father’s 1922 two-seater Bentley. It looked short and squat with its great barrel of a hood, held in place by a heavy leather girth and buckle – big and powerful as a steam locomotive to my child’s eyes. It stood high and ungainly on its huge wheels, more like a motorized carriage than a car… wasn’t it Etore Bugatti who once declared: “Mr Bentley builds the fastest trucks on the road today”? Only the day before, I had been playing in it where it stood in a stable, covered in chicken shit, its tyres flat, its windshield yellow from the ageing of the layer of plastic in the ‘sandwich’ that was Triplex glass. It had been stored there throughout the great uncertainty of the Second World War. Now, ignominiously, the noble touring car was being dragged from its geriatric roost amongst the chickens, past the huge, stark ruins of the medieval castle that stood in jagged dilapidation in the garden: decayed, cavity-riddled fangs of former medieval military might. And now our beloved Benty was gone…

A few years later, I discovered the enormous leather suitcases that were custom-made for the luggage rack of that car. There were two of them, almost one and a half metres long and quite shallow – so one could lay out a full ball gown or suit of tails in one without folding or creasing them. I also found Father’s motoring clothes, worthy of a First World War fighter pilot: an ankle-length, tight-waisted white leather greatcoat, with elbow-length gauntlets and helmet to match. Hardly practical attire for getting in and out of a little biplane, or even a motor car, for that matter. He must have cut quite a figure driving his gleaming, dark green, 3.5 litre two-seater Bentley, tall and slim as he was then, the brilliantly successful, the lionized young novelist that he was, with a dark beard and such a romantic air – that first time in 1931 when he went to stay with Mother’s family in their country mansion.

Father was discovered there prowling around upstairs by a Bavarian cousin, a Baroness Pia von Aretin (who later helped him enormously with his last novel by introducing him to people who had known Hitler when he was on the lam after the failed Munich Putsch) pacing the corridors of my grandmother’s house, barefoot. Naturally, being a well-bred German girl, she waited for him to introduce himself, but all he said was: “Do you speak Chinese?” Of course, his romantic, creative, exotic aura was given another lift. Then, when he went to change for dinner, the valet had laid out a tent for him on his bed! He rang for the valet and asked about his tent: “Well sir, we found not a single bag in your motor, all we could find was the tent and seeing as we’d heard in the servants’ hall that you’d been to Arabia and such foreign parts, we thought perhaps that you might be in the habit of wearing tribal robes instead of trousers and tails.” The aura gained yet another tone of intensity. Mother’s family was at once impressed by his fame, but fearful of the scandalous controversy around his first novel. That children could be such wicked little savages when left to themselves – not the ‘little angels’ brought downstairs by nurses, washed, combed and forced to behave. ‘His’ children managed surprisingly well in the captivity of pirates, much as Golding’s boys later survived on a desert island. Children are not by nature innocents; they are already learning survival techniques.

What a time-warp the Second World War created! Before then, the ‘haves’, the 1 per cent, drove motor cars, which, like their clothing, were bespoke. Mother knew only the name of the Head Gardener, because there were too many other gardeners and, anyway, no instructions were to be given without being passed first through Mr Edwards. He wore a three-piece suit with a gold watch chain across his prosperous paunch. The others, the ‘have nots’, still walked to the pump down the street for water and hoarded coal to warm the house a little on Christmas Eve – coal in your stocking was a blessing, not a scold in those days. This 99 per cent who produced everything, died in wars ‘for their country’ and served the gentry hand and foot. Only, twenty years later, there were no more servants and everyone bought what they could afford and find.

There certainly remained anomalies, such as the barber whom Father occasionally visited in London. I remember the place after the war, with its dark wood-framed bevelled mirrors and great high, stuffed leather armchairs around which glided the Gentleman Barbers, armed with hand clippers and scissors, long razors which they stropped on leather – the same genteel old men who had regularly trimmed the beard of King George V. They were masters of conversation, no doubt researching the interests of the morrow’s client the night before – sport was not the dominant subject as it is today, but gentle mention of Politics, Art, Literature and (for Father) even Sailing! Or Jacksons of Piccadilly, where you could still see an immaculate ‘Gentleman’s Gentleman’ tasting a little aged stilton, only to declare that “His Lordship would not approve, it’s under-ripe, you see”.

In general, while still hugely divided, there had been a giant leap towards egalitarianism. When working on his second novel, Father had consulted a Chinese laundryman (who spoke enough English) on details of local colour from his past. He was researching his next book (which came out in 1938) and when the man mentioned that he would like to open his own laundry, instead of working for someone else, Father gave him five pounds and asked him to bill him when he had used up his credit. He posted his dirty dress shirts to London and they came back immaculately starched and ironed – and he was never asked for another penny – those five pounds had been seed capital that started a small Chinese laundry empire! Not that Father wore dress shirts by the time I was around in North Wales – well, perhaps once a year. He wore modern nylon shirts that he washed himself and hung to dry in the bathroom. Unlike his old friend Dylan Thomas, he had several shirts, whereas Dylan only bought one for his first lecture tour in the States – he said he tried to wash it every night, but since it was never dry in the morning, he always put it on wet next day. Much like the vicar who announced that his dog collar was made of plastic, so he could “lick it clean in the morning and it was ready to wear!”

Sixty years on, I found the car again, when my brother sent me an e-mail with an attachment: a couple of black-andwhite snapshots of it at its very worst, slumped by a stone wall in a small field belonging to our friend Hamish, high up in the Welsh mountains. Pieces of body were hanging down to the ground or removed and loaded onto the seats. Then there were glossy colour photographs of it immaculately restored, with its original licence plate: KU631, outside an expensive suburban brick house somewhere in England, its distinctive body changed beyond recognition. The gracefully long, sweeping wings – so modern for a car built in 1922 – had been replaced by small individual mudguards. The only access door was on the passenger side because the handbrake was exterior. Even the gear stick was on the outside of the driver, though inside the car. This left more room for the passenger and an easier slide-through for the driver when getting in. I suppose it also left no excuse for groping the skirts of attractive young flappers while changing gears. His was the 113th Bentley to leave the workshop, the original body built by a private coachbuilder – as was the custom in those days.

Just as Fords came “in every colour as long as it’s black” and all early Bugattis came in bright blue, so all Bentleys were British Racing Green, a green so dark as to be almost black. It had last changed hands for £75,000. I believe Father had bought it second-hand in 1928 for the phenomenally high price of £2,000 (say, £100,000 today). He was doing well in those days.

II

THE FIRST WINTERS

Was that really my very first memory: when I was six? Or was it, more likely, when I was sitting on my wooden lorry, called Borry, pushing it up the incline of flagstones in a huge kitchen at the age of three? After the Second World War, there were no metal toys to buy, no Dinky or Tonka Toys, just what local artisans could make from bits of wood and nails and wire. That was how Borry was created.

The floor of that kitchen seemed to stretch and slope as far as the eye could see. There was a great, hot coal stove to cook on that kept the whole room cosy. I wonder how we had any coal, in that post-war time of rationing and penury – when women in the cities were queuing up for their coal rations with prams in which to take it home. Yet we seemed to have coal and no doubt that was why I was playing there when it happened. The winter of ‘46/’47 was particularly cold in Cumberland, just south of the Scottish/English border. We stayed there, at Lyulph’s Tower (which belonged to Hubert Howard, one of Mother’s first cousins), for a winter because our house in North Wales was still impractical for winter living. For a start, our new home had no legal access (save by sea) and it was hard work bringing coal two miles across the estuary by boat at high tide. Besides, petrol was still rationed and Father could not get petrol coupons for his outboard motor, so he had to use some of the precious supply intended for the Jeep.

So it was that we spent those two winters in different houses in Cumberland (also known as the Lake District). They belonged to one or another of Mother’s numerous cousins: Howards, the Catholic side of the family. Some of their ancestors had lost their heads rather than renounce their faith during the Reformation of the sixteenth century. The Doyen of that family was John, first Duke of Norfolk (1430-85)… the present Duke is so far removed from my family as to be beyond my sight. Lyulph’s Tower had been built as a hunting lodge almost a hundred years before, in Victorian times, in a bizarre style of ‘Gothic Castle’, a nineteenth-century version of some 1940s Beverly Hills folly. It had a vast kitchen and dining hall in which to prepare and enjoy the spoils of the hunt. Its Gothic style left complicated joints in the roof where great weights of snow accumulated. Leaks occurred where the lead flashing had failed. The leaks wet the heavy plaster ceilings below, until…

Bang! – there was a terrific crash as a huge piece of thick ceiling plaster plummeted to the floor, throwing up a fountain of dust about it. I remember watching, fascinated by the cloud of dust that rose, spread like a mushroom, and then slowly fell back to the floor. The chunks of plaster had whiskers of horsehair (added to the plaster to give it greater structural strength) protruding from its sides, where it had broken off and landed – just where I had been on my lorry only a few moments before. That startled me and no doubt, startled Mother even more.

That time in the Lake District, I first heard the word ‘terrific’ and sensed the exhilaration of a forceful, enthusiastic speaker. I was sitting between two adults in the huge, leather front seat of a Ford Motorcar (no such thing as seat belts then), climbing the driveway of Lyulph’s Tower, that Gothic Hunting Lodge. The car smelled of musty wood, leather and hot oil, that nostalgic odour of old motors which still grabs at my senses as evocatively as certain perfumes. The driver was a commanding old lady and she exploded the word ‘terrific’ with such vehemence that it has stayed in heavy italics with me to this day. It remains associated with the simple replica of an aeroplane that decorated the hoods of those big old Ford Pilots. It gave me visions of planes taking flight – the soaring force, the escape, the flight… all contained in that single word ‘terrific!’ At that age I did not wonder where the precious petrol to run this big car came from, but it certainly was strictly rationed at the time.

I wonder now if that determined lady was our Great Aunt ‘Tiger’, who terrified the whole county with her driving – a style not so dissimilar to that of Mother. They both drove by touch rather than by sight, punctuating monologues by forcefully changing gears – usually at the wrong moment for the car. Tiger had knocked down a ‘pillar box’ or mailbox at the end of her driveway. Pillar boxes were of heavy cast iron, set deep into the ground and painted bright red (how could you possibly miss them?) They were decorated with the Royal Coat-of-Arms and ‘G.R.VI’ for ‘George Rex Sixth’. The Royal Mail and its collection boxes were the property of the Crown and their abuse a serious offence. Nevertheless, when Great Aunt Tiger was summoned to the magistrate’s court, she stormed in with all guns blazing, upbraiding the sixty-year-old magistrate with: “Now listen to me, young man, that pillar box was placed in a most dangerous position. Someone was bound to run into it sooner or later. It must be moved to a safer place!” It was moved and Great Aunt Tiger continued to terrify the neighbourhood by driving around for many years to come.

While the War was in its final, desperate death-throes – successful at last thanks to Roosevelt’s skilful manipulation of American opinion, I had already managed to half cripple my left hand by holding onto the heating bar of an electric heater. It was off at the time, but incorrectly wired, so that even when turned off, electricity still flowed when given the ‘ground’ of a crawling infant. I was too young to have any memories of this, but I was later told that my youngest sister, three years my senior, was so terrified by my blackened hand that she screamed until Mother came and picked her up – ignoring, for the time being, the source of her horror: the hand! Well, that falling ceiling missed me too. How many lives does one have? At least in North Wales there would be no danger of electrocution – we had a twelve-volt windmill charging four tractor batteries. They were usually so worn out that the light came up and died down again on the whim of the wind as it freshened and failed – much as a sailing boat drifts to a standstill in a calm, then lists to the wind and leaps forward again. No, there was no danger of electrocution here!

Ten years later, my middle finger was still so bent from the burn that it threatened to grow into my palm. I was sent to a hospital for plastic surgery. The hospital had been built during the Second World War to patch up disfigured fighter pilots. It still looked like an army barracks but now it treated hare-lips and obtrusive ears in children, besides casualties of fires and accidents amongst adults. In three weeks the surgeons did miracles and the finger is as good as new.

Nor could I escape electrocution forever: in the sixties I was installing a kinetic art show in a gallery on the Boulevard St Germain, in Paris. Noon came just as I was in the middle of some complex wiring, but when the six artists setting up their own works called me to lunch, I dropped everything in midstream and we all went round the corner to a neighbourhood bistro for a well-lubricated lunch and much enthusiastic discussion. We were just behind Les Deux Magots, hangout and workplace of Hemingway, Sartre and Camus – but it was too busy and expensive for us proletarian workers. Upon our return an hour later, what I had been doing had escaped me and I had forgotten what I should do next. I decided simply to pick up where I had left off and hope it would all come back to me. The metal-handled wire cutters were still there on the floor where I had left them, right next to the wire which I was about to cut. The bang threw me right across the room. I could see the wire was still plugged in – the outlet smoking ominously. My wire cutters were perfectly melted to use as wire strippers with two small rounds melted in the cutting edges. Could that have been why I moved to America, where the voltage is 110 instead of 220?

The next year, in this peripatetic, half-homeless life, we spent the winter in a real medieval castle called Naworth, also part of the Howard fiefdom in Cumberland. It had been converted into four living units, each with a corner tower and one long, narrow, habitable wall of rooms. Father wrote in the great gallery, a room perhaps a hundred feet long, lined with portraits of ancestors – ideal for pacing to and fro as he cogitated.

Alas I was too young to participate in a battle, organized by my older siblings. The children of the castle defended it against an onslaught of neighbouring friends and cousins. They used paper bags full of flour and the fire hoses and stirrup pumps intended for serious defence of the castle in a conflagration. Everyone finished up looking like papiermâché puppets. The courtyard was partially flooded from the fire hoses and in the night it froze. Next day I went sliding on the ice and Mother broke her coccyx, falling on some outdoor stone steps. She had to sit painfully on a doughnut-shaped cushion for many weeks thereafter.

I do not know if we were really hungry in those days (as one of my sisters tells me), but I do remember where Mother had hidden the precious, rationed ingredients to make a Christmas pudding. There were raisins, sultanas and lots of sugar. I had never before seen such sweet bounty and soon made myself thoroughly sick out loud (as Mother too graphically termed the act of vomiting!) I am sure I was severely punished and no one, myself included, was happy with the greatly diminished size of the pudding. However green I looked after being sick out loud, it did not stop me from going to Mother one day and saying: “Owain’s pale and weakly, Doctor says he needs more choccy.” Disgusting child that I was…

On Christmas Day, I was in bed with my youngest sister. We were exploring our stockings – what could be more wonderful for two very young children to find in their Christmas stockings than a whole fresh honeycomb from a neighbour’s hives? We scooped out the honey with our fingers until they went right through the wax on the other side and honey flowed stickily everywhere. I particularly remember how delightful it felt between my toes… until some grown-up came with harsh words and clean sheets.

That winter, I often played with a boy of my age and eventually caught whooping cough from him. His father owned a four-seated air taxi. At the time, the favoured cure for whooping cough was to fly in an unpressurised plane to 5 or 7,000 metres… so, from whom better to catch the wretched bug than the son of the owner of an air taxi? I loved the flight, soaring over the rolling lush green hills and dark, almost black tarns or inland meres of the Lake District and buzzing Naworth Castle until people came outside and waved… but I came back still whooping, while my friend shook it off.

There was a biochemist friend of my Parents, who had inherited some vast expanse of highland with its peat bogs. There was an old tradition of cutting blocks of peat and drying them for sale as a heating fuel. I remember the miles of narrow-gauge railway tracks across the moors with small wagons pushed by men to bring in the harvested peat blocks. This friend decided to set up a factory to make other products from the peat. After each product was produced, there was always a by-product left over which he made into something else until finally there was a colourless, odourless, slightly viscous material with high heat-retaining properties – he sold it to an ice cream factory as an additive filler. That was the part I remember so vividly, though it would be some years before I actually tasted this mythological treat known as ice cream.

Soon after the whooping cough interlude, Mother and I flew down to North Wales with our friend the air taxi man. I remember clearly how we circled low over Snowdonia. The day was sunny and clear; each rock and each path stood out vividly below. The grass was emerald green, the lakes the deepest blue and the craggy rocks in greys and blacks. There were many tiny walkers and climbers below, wearing bright clothing, hiking up the easier paths. The exhilaration of flying over this scene was god-like. I caught another bug up there in that tiny plane: from then on, I wanted to know those rocks and crags and precipices intimately. I wanted to break them as one breaks a wild stallion. I wanted to learn to conquer them by scaling their rugged heights and scrambling over them.

Almost twenty years later (as a young man) one Easter day in Paris, I flew once more over those brilliantly clear mountains, crags and lakes – this time without a plane, just on the power of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony which entered my eyes as a full-spectrum rainbow and left through my outstretched arms, from under my fingernails. The rainbow flowed through me and supported my flight as I turned left and right, sweeping up like a raven on the updraft, then gliding down into the valleys. Later that day we ran through the courtyards of the Louvre and saw the significance of architecture as it defines the open space within it, just as much as it exists in the form of walls, floors and windows. For the first time, I saw and appreciated empty space as architecture. Now I came to understand that you can construct empty space as an edifice by defining that space with walls.

Suddenly, the bouncing of the aircraft on the multiple up and downdrafts over the mountains took its toll. The pilot quickly handed me a paper airsickness bag. Once used, he slid open the cockpit canopy and tossed it out… I had a dreadful image of the bag landing squarely on the unsuspecting head of a passing, sweating hiker… but was assured that it would disintegrate on the way down. Anyway, when those hills did indeed become my playground and I hiked for days and nights on end, I never feared being crowned with a vomit-laden paper bag. For one thing, it’s very tricky flying in these mountains, with such violent thermals and I have no recollection of ever seeing light aircraft flying low over those mountains. Many a mountain rescue helicopter has crashed. Endangering oneself is one thing, but doing so endangers many others.

We flew on south towards our house on its estuary and located a field a mile or two away, where the locals said a small plane had landed during the War. It turned out to be surrounded on all four sides by power lines, besides having high banks underneath with hedges growing on them. The surprised pilot said it was quite impossible to land there. Even if he could fly under the wires and over the banks and hedges, he could never take off again. We flew on and tried the beach of the estuary in front of our house. We must have radio-telephoned Father, because he was already on the beach with our American Army Jeep, waiting for us.

The pilot thought he could land where there were ‘car tracks’ on the sand, but one very tentative touch-and-go threatened to flip the plane over in a somersault and he was not prepared to try again… Father in his Jeep had been driving on soft sand which was totally unsuitable for landing. By this time, most of the anti-aircraft poles (of which, more later) had been removed, but the sand remained stubbornly deep and soft.

We flew west, towards the open sea and there, by the salt marshes where I would later spend happy hours trying to shoot wild duck, we found an unobstructed field. Hoping that there were no rabbit holes to catch our wheels, we landed with some wrenching bangs, bumps and bounces. That was where Father finally chased us down. Later, we learned that the famous field where we had first tried to land had killed the pilot and crew of the only aircraft to land there – a fatal crash-landing due to engine trouble! A small detail that was missing in local lore which might well have made all the difference in the recommendation…

III

HOME

On the edge of a great tidal estuary, twice daily transformed from sea to sand to sea again, sits a simple square white house. It was to become our long-term home over the next thirty years. The tides from the estuary come in from the Irish Sea, which is warmed by the Gulf Stream from the Caribbean. It sweeps all the way up the east coast of the United States, then across the North Atlantic, before embracing the coasts of Brittany, the Scilly Isles and up between Wales and Ireland. Yet it remains a current warm enough to temper these latitudes. At sea level, a freeze is exceptional; a few hundred feet up and away from the sea, it’s a very different story. The opposite shore is a rocky promontory (dividing twin estuaries) that had belonged to a wealthy amateur botanist in the nineteenth century. He had brought back specimens of rhododendron from Nepal, bamboo from China and redwood from California and had planted a lush forest garden on the promontory, to this day called the Gwyllt (or ‘Wilderness’). His large house, with its tall, barley-sugar chimneys, nestles down on the edge of the tidal estuary, constantly changing from sand to sea or sand and sea. The property was bought by the celebrated architect and environmentalist, Clough Williams-Ellis in the mid-1920s and converted into an eccentric hotel, his ‘Experiment in Sympathetic Development’: Portmeirion. From our house, a mile away, it looked like a brightly coloured Italianate village in the distance. He denied being influenced by Portofino (which he must have known, even then, but the parallel becomes more evident further on in this story). As a very young child I had precociously declared that Portmeirion had been built during the ‘Early Ice Cream Age’… what did I know of ice cream at the time? The hotel remained a magical mélange of architectural styles, a mirage in my mind. As for the frozen dessert, I had to wait for refrigeration and the end of sugar rationing… for Britain maintained food rationing until 1954 largely because of the cost of maintaining its armaments (three full Naval fleets and one-hundred-andtwenty RAF squadrons worldwide).

The estuary is a mile across and some days, when the sun shines, the shadows of clouds chase each other across the brilliantly-lit expanses of sand and water, bringing a rapidly-changing light, like a fast-forward film of clouds. Ever changing from grey to bright light – moody as Mother. It was true that Father could also explode like a thunder-clap when disturbed by children’s games. He had a huge voice and large presence. His anger was an avalanche or violent squall, driving us noise-makers into submissive silence and seclusion. Some child once remarked that: “Daddy’s thundering again.”

The situation of the house was remote and wild beyond what one might imagine of Britain – and indeed remains largely unspoilt to this day. True, we could see the hotel a mile away across the estuary and a few other houses appeared as tiny dots still further off. On the far side of the twin estuary stood the small, silted-up harbour town of Porthmadog, but that is two miles away. On a very still night, one might hear the train a mile and a half away, but otherwise there were no sounds of civilization, no cars, or trucks, or buses. Our neighbours on either side were several hundred yards away. To the east was old Mr Edwards (the farmer) who had no motor, save his son’s old lorry for the hay harvest. To the west stood the house of old Mrs Thomas who must have had some money because she drove a little old Ford from the 1930s, but with petrol rationing, she used it only once every two weeks. Since none of us had electricity, motor mowers, chain saws or today’s other noisy contraptions, the only noise was the sound of the seagulls, the wind and perhaps the waves at high tide. In the isolated silence, we could hear the blood pressure pounding in our ears – a rhythmic reminder that we were alive, but certainly no proof that anyone else in the whole wide world was also alive…

Then the clouds would pour rain here and there on the scene, while all the rest remained in bright sunlight. Much of the time, the mountains to the north were shrouded from view by thick cloud and sometimes, even the mile-away coast opposite disappeared completely and rain would pour down for many days on end. We spent day after day reading, until our Parents went out. Then, in holiday times, when some of my siblings were around, we could burst out with our raucous indoor games.

Behind this little oasis of lush gardens and colour on the opposite shore, rise the sharp peaks of the Snowdonia range, craggy summits soaring from treeless slopes, snow-clad during the winter months, an ever-changing view of spectacular depth. Squalls of grey rain clouds would veil the brilliance of blue sky. The mountains themselves turned from pale blue in the misty light to deep blue in clearer light or were veiled completely, those sharp crags far away, inaccessible as a Romantic painting of the eighteenth or nineteenth century, frameless as the open sky. They were intangible in their distance. The very concept of access, the idea of walking their slopes, climbing the crags seemed quite inconceivable – yet in fact is so very real. At times, there was a brooding calm but again later, it could be fierce and tempestuous, ferocious, magical. It was a constantly shifting scene. This is no theatre backdrop, but natural scenery. This is the view from our family home. Sixty years later, it is a view that still takes my breath away when I get out to open the farm gate at the top of the hill behind the house and look down over the vast panorama when I visit it again, (after an overnight flight from New York to Manchester). This is the view that I have left behind. It belongs to another life, a could-have-been life that I do not, for a moment, regret not having pursued.

This white house was built in 1911 to serve as a base for a headmaster (John Chambers) and his family, while his pupils camped in a field next door. An additional wing was added after the First World War. It was never intended as a year-round residence, so our eight-bedroom home was very simple, even utilitarian – but the situation spectacular. Behind it rose a small hill, the ‘Ynys’ or Island – for it was a tidal island until the end of the nineteenth century and going back seven hundred years (when Harlech Castle was built) it was a full-time island with access only by boat or perhaps at low tide over the sands.

In those early days, Arthur Koestler (the intensely engagé Hungarian writer) and his wife Cynthia had come to dinner with us in Wales, despite the difficult access to our house. Afterwards, Father escorted them the half mile, in the pitch-black night, along the sea grass that was carved by deep gullies where the tide ran out and edged the estuary, to where the old driveway was washed out and came to an end, where their car was parked. The tide had risen, leading Koestler to remark that he was almost drowned on the way back. “Nonsense,” said Father afterwards, “he never stopped talking for a second, I would have known at once if he was drowning, there would have been a moment’s peace!”

The estuary used to be forked, the northern part having been dammed in 1811 to create arable land on that reclaimed branch. The southern fork, where our house stands, is still tidal: twice a day, the seven by one mile estuary is transformed from sand with a few streams in it, to being completely full of water. At spring tides there can be a vertical rise and fall of up to 11.5 metres. Tides governed whole sectors of our lives and respect for the lethal currents was in our veins. To this day, tourists drown where we children played. For one thing, the warning signs are usually illegible and, even when they are decipherable, often only in Welsh. At home, the tide table always hung on a string in the ‘telephone room’, to be consulted before planning a dinner, accepting an invitation or making any other daily plans, whether building sand castles, setting and cleaning the nets, baiting the night-lines, collecting the fish, going sailing, riding or shooting.

Our family was broadly divided into two camps: sailors and horse people. Father headed the first, though he also rode well enough to have gone pig-sticking for wild boar in Morocco, where a fall during the chase could be fatal. The second camp was under Mother’s tutelage, though she too could row a dinghy with the best in an emergency. My brother (the eldest of the family) and my eldest sister were sailors, while the next two sisters, horsewomen. As we were of an uneven number, I fell between the two camps, though it was impractical to be a member of both sides. The amount of upkeep demanded by old clinker-built wooden boats on one side, and ponies and horses on the other, made adherence to both at once just too much work. There are not enough hours of light in the day. We could all do both, but we had our preferences and priorities.

I wanted to be a sailor (and have been all my life) but my horse-riding sisters could not resist the urge to use me as a jockey in one-mile pony races. I was young enough to be in a special class and light enough to race the smallest pony. Apparently, I had cold feet at the last moment before my first race at the age of seven, and had to be given Dutch courage in the form of hard cider, which was more alcoholic than beer. After a large glass of that, I forgot my fear, raced as if the devil was on my back, missed the last post in a haze of alcohol and started to retire – only to be told that everyone else had already missed several posts. I turned back into the race and just won it anyway. My sisters had another red rosette to hang in the tack room!

There were occasional squabbles between the two factions. Had the boat people stolen the grain scoop to use as a bailer? Had the horse people stolen a line to tether a horse? I never bonded with horses and later experiences have done nothing to elevate things equine in my estimation. I rented a knock-kneed skeleton of a horse in the Taurus mountains of southern Turkey, only to have it fall off the path we were on and roll down the mountain with me and my camera underneath. The camera fared even worse than I. In fact, nowadays, I think: “the only animals more stupid than horses are the ones that sit on top of them.”