Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Origin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Imagine eleven fields grouped around the houses, one hundred and eighty-six gently brae-set acres, sloping away to the south and west. And then imagine woods and fields stretching far and far along the valley into the blue mists of a summer afternoon, until the hills joined hands in one coned summit across the horizon, on the very marches of infinity. In that spare but not unlovely land I of the sixth generation grew up to be a farmer's boy'. John R. Allan was brought up on a farm in Aberdeenshire at the beginning of the century. Through his child's eye we are allowed a view of the little world called Dungair, with its extended family of colourful characters - among them the Old Man, Uncle Sandy, Captain Blades and Cuddy Manson. We are given a vivid, yet unsentimental account of the boy's explorations of his surroundings, his early schooldays, his first visit to the town and his awareness of the outbreak of the Great War. New material continues John Allan's life story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 267

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

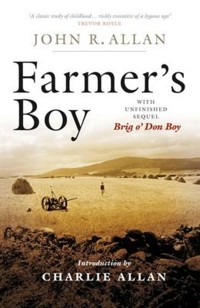

Farmer’s Boy

This eBook edition published in 2013 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 1935 This edition published in 2009 by Birlinn Limited

© The estate of John R. Allan, 2009 Illustrations © the estate of Douglas Percy Bliss, 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-84158-822-3 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-754-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

TO WILLIAM MORRISON

In Memory of The Scots Observer and the

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

I The Family

II The Little World

III Unwillingly to School

IV Betsy and William

V The Steading

VI 1914

VII War and Peace

Brig o’ Don Boy

Glossary

Illustrations

Four generations at Dungair

Aulton Market

The Boy and his Grandmother in the garden

Uncle Sandy

Sally

Singing ‘cornkisters’

Preaching to the poultry

On the way to the Picnic

In the rickyard

Foreword

By the author’s son, Charlie Allan

‘You’ll never be the man your father was.’ I was subjected to that peculiarly Aberdeenshire ‘tak doon’ often as a boy and as a young man. Perhaps oddly, I was always rather proud of it. My father was a very agreeable, witty and generous person and universally popular. An unlikely hero, he entered the war as a sapper and was demobbed a captain without ever leaving the country. He was persuaded to do his bit for the Labour Party in 1945 and came within two thousand votes of unseating the great Bob Boothby. There was never a more thankful loser. He was a fine player at golf, tennis and bridge. Farmer’s Boy was published before he was thirty. I always thought that I would have plenty of scope even if I could never be the man he was.

Farmer’s Boy is a work of such maturity and perfection in the use of the English language that people thought the author must be old. For more than fifty years after its publication people used to be astonished that my father was still alive.

Which raises the question: why did a talent that flowered so early not leave a bigger literary legacy? Why are there not more than the nine books, including one novel published posthumously?

There are two reasons, apart from the years wasted by the war. The first is John R. Allan’s success as a broadcaster, but more particularly as a writer for radio. Between the late thirties and the mid-fifties he wrote hundreds of plays and illustrated talks, many for schools. He even had his own sitcom whose heroes were staff at Dreepieden railway station. He made what seemed like a lot of money but it took a great deal of John Allan’s time. And the trouble with radio is that it leaves nothing for posterity.

In 1952 John Allan published his definitive work, The North East Lowlands of Scotland. It is his masterpiece and the masterpiece of that different part of Scotland. Two years later he almost died of pneumonia complicated by cirrhosis of the liver. He never recovered his full vigour and at 49 his career was effectively over. He wrote his potboiler (a popular weekly article for the Press and Journal) but he wasn’t fit for anything more serious.

His last 31 years were full of frustration as he toiled to finish several novels and the sequel to Farmer’s Boy, the first part of which, Brig o’ Don Boy, is published here as a postscript. He just didn’t have the strength for more.

To the Reader

This is not an autobiography. It is an imaginative reconstruction of the past, based upon the relations of an old man, an old woman and a young boy. The more distant the past, the more imaginative the treatment: therefore no attempt should be made to identify the characters with men and women so long dead. Nothing would grieve the author more than that, in thus attempting to re-create the spirit of a society which has now disappeared, he should do disservice to any of those whom, though he knows them only by hearsay, he loves this side idolatry—his ancestors.

I

The Family

I was born on the afternoon of the day on which my grandfather signed his third Trust Deed on behoof of his creditors ... the only form of literature in which our family have ever achieved distinction. Though the circumstances of my birth were not such as to cause him any great pleasure, and though his own circumstances were even more involved than usual, the Old Man abated nothing of his usual intransigeance in the face of fortune. When the creditors and their agent had departed, the midwife, an ancient and disillusioned female, presented me to the Old Man. The two generations, I am told, looked at each other in silence across the vastness of seventy years, then the Old Man delivered his grim judgement:

‘Gin it gets hair an’ teeth it winna look sae like a rabbit.’

And so she left him.

‘Aw weel,’ said the Old Man, thinking over the events of the day, ‘we’d better jist mak a nicht o’t.’

He thereupon invited a few old friends, neighbouring farmers long tried in the mischances of this world, to come over that night for a game of nap. They came. They hanselled the new child and the new Trust Deed in the remains of the greybeard and the Old Man collected thirty shillings at nap before morning. Such was the world into which I made my entry on a chill December morning about thirty years ago.

Our family could boast of age if not of honour. We could go back for five generations to one James who was reputed to have been hanged for sheepstealing about the middle of the eighteenth century. All my researches have failed to prove the authenticity of the legend, but I am quite sure that, if James existed, he deserved hanging, whether or not that was his fate.

It was in the first years of the nineteenth century that my grandfather’s grandfather came to Dungair. At that time it was no more than a windy pasture between the moss and the moor. By the terms of his lease he had to bring so many acres under the plough within a term of years and make certain extensions to the steading. Nothing at all has survived of this ancestor, beyond the fact that his name was John, that he married a wife by whom he had three sons, and that he died in 1831 in the sixty-second year of his age.

Did I say nothing of his personality has survived? I was wrong, for he took in sixty acres from the moss and the moor, manured and ploughed them and gathered ever-increasing harvests from them. He died in the middle of October and his last picture of this earth may have been the stooks row on row in the Home Field, twenty acres of grain where there had been only rashes and heather before he came. The stooks were his memorial and every fifth year they stood there to his honour, and so will stand as long as harvest comes to Scotland.

John had three sons—Alexander, David and William. David was a good youth, who grew up into a pious man. He was a potter to trade, a great reader in a muddled sort of way and a model to the community in all things. Unfortunately he was left a widow man with one child when he was forty. As there were no unattached female relations available (our family has never bred daughters), David had to engage a housekeeper. Bathia was a rumbustious creature of forty-five who completely altered David’s life. She believed in the Church, was a connoisseur of funerals, but she could not be doing with books. David’s muddleheaded studiousness and respectability appalled her. She set about changing all that. A lot of nasty things were said about her, but I think she had only the best intentions. Anyway she certainly jazzed up David a bit. First of all she gave little tea parties. Then porter and ale parties. Then they had a grand wedding at which only the fact that one of the police was best man saved the whole crew from being run in. David’s second go of wedded bliss was not exactly one long sweet song, because there were too many mornings after, but he and his good lady certainly did add to the gaiety of the village in which they lived. And David enjoyed it. When anyone spoke of his first wife he used to sigh—but people were never quite sure that he wasn’t thinking of the years he had wasted on her goodness.

Four generations at Dungair

William was altogether a simpler case. He was a roisterer from birth. If there was any mischief to do, he did it. If there was blame to be taken, he took it. If there were girls to be kissed, he kissed them. He took no thought for the morrow, but ate and drank and flourished like a sunflower. He was tall, broad and red-faced—a masterful jolly man, fit to be a publican. And a publican he became in a sort of way—at least he also married a widow and together they ran a discreet little alehouse in a discreet back lane. William was one of his own good customers, and thereby achieved his great distinction, which was half a nose.

It happened this way. William had been drinking all morning with his friend Sandy the butcher and, when Sandy announced that he was going back to the shop to cut up a beast, William insisted on going with him. After the usual amount of drunken argument, they decided that William would hold the beast in position while Sandy hacked it up with the cleaver. They got to work. Unfortunately William’s legs were not as steady as they might have been, nor Sandy’s aim as accurate. No matter whose was the blame. Sandy fetched the beast a mighty whack with the cleaver but missed and sliced off the point of William’s nose instead .... Sandy was terribly sorry of course, but William always made light of the accident, though his wife used to say that he never looked the same man again.

Alexander was a better man than his brothers. He had the same physical appearance which persists in the family even to-day—the hard round head covered with thick black hair, the broad shoulders, the deep chest, the rather short legs and the general aspect of an amiable bull. He liked good living, by which I mean dancing, drinking, putting sods on the tops of neighbours’ chimneys, and courting every pretty girl within ten miles. He was a roistering young man who seemed destined for the Devil, but he had one great passion which gave him a true bearing among the devious ways of his pleasure. He loved Dungair with a constancy and devotion that he never showed towards any human being. He was extravagant; he was splendidly generous and he was an indifferent business man, with the result that he was always poor, but no matter who should have to make sacrifices it was never the farm. It would have been easy enough for a husbandman of his skill to have cut down the supply of guano for a year or two without doing any great damage or showing the nakedness of the land. He would far sooner have gone naked himself. Good husbandry was his point of honour—a point cherished to idolatry. It was his religion, perhaps the only religion he ever had. It was his one ideal and he never betrayed it. When he came to die he too left his memorial in the sixty acres he took in from the moss and moor, and in the richness which he had added to John’s rather grudging fields. He left more than that, for all his descendants inherited something of his care for his beloved acres. John was the pioneer, but Alexander was the Great Ancestor. He died in 1878, aged sixty-nine.

I am loth to pass on from Alexander, for he is the one member of the family who has had anything of greatness in him. It was not only in his devotion to Dungair that he was great. He could go into any company of men as an equal. Remember that he was only a working farmer—not even a bonnet laird—yet he was one of the best known figures in town. He took his Friday dinner in the Red Lion at the same table as the Provost and the Dean of Guild. He carved his portion from the same joint as men who could have bought and sold a thousand of him, because they respected his craftsmanship in the art of life as much as they enjoyed his broad salt wit which never spared them. Of course life was simpler then. Our town was more intimate, more domestic. A man could find his proper place and be at ease in it. It was the golden age of personality and bred a race of worthies—but none was worthier than Dungair. Take him where you like, he was a whole man. His descendants are only weskits stuffed with straw.

Alexander had six children, four sons and two daughters. There had been five others but they died in childhood, none of them surviving beyond eight months. They would not have been unduly lamented, for stock-breeding teaches a man to face life and death with a certain realism. Perhaps their mother wept for them a little when she had time. That’s what women were for. Susan is a shadowy figure about whom her children had very little to say. She died when she was fifty, being then a little queer, which is not altogether surprising.

Alexander’s sons were John, Francis, Simon and George and his daughters were Jean and Margaret. George, the baby, was a delightful person, a natural of the most engaging kind. If he had been less happy he would have been a poet. As it was, his life was a blameless lyric. He had no inhibitions, no morals, and fortunately no great appetites. His passion was animals. Cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, goats and mongrel dogs were all alike his little brothers. Like a wise elder brother he protected them and like an elder brother he quite frequently thrashed them. But there was no malice in the thrashings and they seem to have understood it. Certainly he never meant to be cruel—a kinder and more benevolent little man never lived—and if he saw anyone maltreating an animal he became almost homicidal. I never met him, but I have heard so much about him from my grandmother who loved him and loved to tell me about him, that I feel as if I had known him all my life. He seldom left Dungair, for he was a little shy of strangers, though perfectly self-possessed if he had to meet them. He preferred to stay at home, where he was cattleman, singing as he worked in the byre or fraising with the beasts with whom he was on the most familiar terms. His only incursion into society was his attendance at the dancing class held every winter in the Smiddy barn. He attended that class for twenty-two years and never managed to learn a step, which was very peculiar, for he often used to dance a minuet to his own whistling when things were going by-ordinary well with him. I rather think he went to the dancing class in order to show off his grey bowler hat of which he was very proud, because he ceased attending the class about the time when a family of mice made their nest in it and he became so devoted to them that he could not bear to turn them out. A lot of people, including his brothers and sisters, thought that George was mad. Only his sister-in-law understood that he was beautifully sane. He adored her and was always giving her little presents of flowers. Sometimes, when she had been more than usually kind, his gratitude became embarrassing, as on the day when he presented her with an orphaned hedgehog of an extremely anti-social temper. Of course George had no idea of taking care of himself. One winter night when he was in bed with a bad cold, he became worried about a score of ewes folded up on the moor. He rose at once and, with only a coat over his nightgown, went up to them through the slashing rain. That finished him. He took pneumonia and died in the thirty-ninth year of his age. Everybody mourned for him, especially his elder brother, for he had been a wonderful cattleman and never asked for wages. His sister-in-law mourned for him too, for there were no more flowers, nor any grim unsocial hedgehogs.

Simon was another remarkable character. Like his grandfather he was a pioneer—but in a very different way. He took to learning. Not that he ever became a scholar, but he had ambitions in that direction. He got the same schooling as the others—the privilege of hearing old Mother Kay damn the weather, the crows and himself till he was twelve. Then he was taken home to work on the farm. The good brown earth that the novelists write about took him to herself for twelve hours a day, and after twelve such hours a man had little taste for anything but a chair by the ingle or a walk in the gloaming with a young woman. Yet Simon had the strange impulse to learning in him. Maybe he had the ambition to wag his head in a pulpit; maybe he wished to be a schoolmaster; maybe he just wished to know. Whatever it was, he began to study the Latin when he was twenty, struggling with the rudiments at the bothy fire while his companions played the fiddle or told strong country stories. We must feel very humble, we who get our learning handed to us on a silver plate—when we think of Simon sitting down to unravel the vagaries of the subjunctive, after twelve hours at the hoe. He could never have hoped for any real reward. His must have been a pure love of learning for itself, without any motives of preferment—unless he was like an old shepherd I once knew who collected terms like ‘quantum sufficit’, ‘e pluribus unum’, and ‘reductio ad absurdum’, in order to swear the more effectively at his dogs. Simon did not get very far with the Latin. At twenty-three he married a wife who taught him that life was real and life was earnest when you had to get meal, milk and potatoes for a family of nine. His brother John helped him into a very small farm where he spent a laborious life sweetened only by an occasional taste of the wonders of science as revealed in odd corners of the still very occasional newspaper. He was a kindly, simple man to whom the world was full of unknown but dimly apprehended mysteries, occluded by a voracious and too self-evident family. He died in 1905, aged fifty, leaving behind him eight children who never did much to justify themselves except produce children of the most conventional urban type.

Great-uncle Francis was another family pioneer. He discovered the Trust Deed racket which my grandfather was to carry to perfection. His father settled him in a small farm but did not give him enough capital to make success even remotely possible. Somehow he managed to carry on for fifteen years until his affairs became so embarrassed that he had to sign a Trust Deed on behoof of his creditors. He then found himself cleared of all financial worries, a situation so strange that he died of it. That is all there is to be said about Francis. It required the superior wits of his brother John to see the Trust Deed as a perpetual haven of financial rest. Francis died in 1884, aged thirty-nine. His widow married a plumber in Dundee and was never heard—or thought of—again. He had six children, all of whom went to foreign parts. Only one, as far as I know, achieved any distinction, he having been bumped-off by an almost famous gangster in a speakeasy in Chicago a few years ago.

My grandfather was the eldest son and inherited many of Alexander’s enduring qualities, such as his love of Dungair, his contempt for business, his generosity, his philoprogenitiveness and his short strong figure. When I knew him, he was an old man whose sins were coming home to roost on his dauntless shoulders, but they tell me he was a splendid man in his potestatur. When I was a not so little boy we used to drive to church every Sunday, the Old Man and I, in a pony trap drawn by an old white mare. The venerable old gentleman sat high above me on the driving seat with his antique square hat—something between a bowler and a tile—and his square white beard, a ripe old pagan casting a wise eye over the fields he loved so well and the people he despised so truly. The church-going was a rite which he always honoured though he held all religion in contempt, and I am sure those Sunday morning drives through the woods, while the bell sounded so graciously across the shining river, were the pleasantest hours of his life. During the sermon he would lean back in the pew, fold his hands across his stomach, and, fixing the Evangelist in the south-east window with a hard blue eye, would enjoy in retrospect all the wickedness of his diverting life. When the service was over, we went out into the sunlight again, yoked the white mare into the trap and drove home through the woods, while the jingle of the harness mingled so melodiously with the cooing of the pigeons. Every now and then the Old Man would mention some worshipper who had been in church that morning and add a biographical note of which I was too young to understand anything except that it was scandalous. To this day I have never understood why the Old Man went to church, but he may have thought that his presence would be a strong antiseptic against the parish becoming too much infected with religion. On the other hand, church may have been just another place to go to and he was a great goer-to-places.

He had been a famous figure at fairs and markets since ever he became a man. Any fair or any market came alike to him, but his favourite diversion was the Aulton Market, held in the beginning of November on the glebe of St. Machar in Old Aberdeen. The fair was of very great antiquity and even when I was a child it was one of the leading events of the social year. The war killed it as it killed many other ancient institutions. The last time I saw the Aulton Market there were no more than a dozen horses on the field, and no gingerbread and no whisky tents. How different thirty, forty years ago. Maybe five hundred, maybe a thousand horses changed hands that day. The whisky tents seethed with roaring drunken crowds. Great piles of gingerbread and chipped apples (a handful for a penny) melted off the stalls like snow wreaths in thaw; roistering farmers staked their shillings in hopeless attempts to find the lady or spot the pea; fiddlers played reels, pipers piped laments, boxers took on all comers for a guinea, and ballad singers made the afternoon hideous with the songs of Scotland. As the evening came on, gas flares lit up the lanes between the booths, making the shadows yet more drunken as the wind troubled the flames. The town people now came in for their evening’s fun—engineers from the shipyards, papermakers up from the Don and hundreds of redoubtable ladies from the Broadford mill. Though the twin spires of St. Machar stood raised like pious hands in horror, and though the tower of King’s College maintained her aloof communion with the stars, the saturnalia roared and swirled unheeding on the glebe. And in the middle of it all where the pipers and the singers and the fiddlers were their noisiest you would find Dungair.

The Aulton Market was the scene of his greatest ploy—certainly of the one which gained him the greatest renown. Strangest among the strange creatures attracted to the market was a crazed evangelist known as the Pentecostal Drummer, so named by Dungair because he used to beat a drum at street corners and call on the nations to repentance. Now it so happened that the Pentecostal Drummer had marked down Dungair as a brand specially allotted for him to pluck from the burning. On this particular market day he took to following him round and round the field so that, as soon as Dungair stopped to have a dram or pass a joke, the Pentecostal Drummer pitched his stance at his side and called on him to repent, banging the drum the while. Not only that, but he had a board on which there was a lurid drawing of Hell and in red letters—‘Beware of the Wrath to Come.’ No matter where Dungair went he found the board stuck up in his face. There is only a certain amount that a man will stand even at the Aulton Market. Dungair grew so annoyed with the Pentecostal Drummer that he suddenly caught up the board and gave him the weight of the wrath to come full on the top of his head. The Pentecostal Drummer showed fight by aiming a kick at Dungair’s stomach, but the Old Man side-stepped, caught the drum in his two hands, and brought it down with such force on the Drummer’s head that it burst and jammed right over his shoulders. He then gave the Drummer a smart crack over the ankles with his staff which so alarmed the poor man, blinded as he was by the drum, that he let out a hollow booming yell and set off with a bound, crashing into people right and left, till he finally came to rest in the ruins of a gingerbread stall. Dungair now felt that he had done enough for honour’s sake, and left the Drummer to square matters with the gingerbread woman, after impounding his board as a souvenir. Some time later in the night he made a tour of all his favourite changehouses, bearing the board aloft, like a banner with a strange device. And that was how he came to be known for many a year as ‘The Wrath to Come’.

Aulton Market

My grandfather was thirty when my great-grandfather died. As he inherited the lease of Dungair and the headship of the family, he found himself under the obligation to take a wife. That can have presented no difficulty, for he had already a notable reputation as an empiricist. Within the year he chose the daughter of a neighbouring farmer, obtained favour with her parents and married her. There is no record that she loved him, There was even a legend that she had a romantic passion for a landless youth from the next parish. And yet I am not so sure, for I once heard her confess, half a century later, that he was a braw man in his big black whisker. It was considered a good match because, if a girl got everything else, she should not expect fidelity. The strange thing is that, however much she had to go without in the hard years to come, she always did get fidelity. It is no business of ours what passion there was between them, nor was I ever privy to their tenderness, for embraces are unseemly on old shoulders and they had an inviolate native dignity. She respected even his faults and he respected the greatness that could respect them. Perhaps there were storms when they were younger, but they were lovely in their age. There was peace in their house when their children left them, and the love with which they cared for me must have sprung from some splendid faith in life, for they were old and could never hope for any reward, nor, as far as I know, did they ever get it.

A few years ago I met an ancient gentleman who used to be our neighbour. He was one of the oldest men I have ever seen, a tiny old man, dried and blanched, like a wand of grass, so that, if the north wind had passed over him, surely he would have been no more. It was a summer day when I went to see him. He was sitting at the window of a blue sunny room, looking over a small garden full of violas and yellow tea roses, and warming in the great sun the tiny silver flame of life that still burned in his ancient body. He knew me as soon as he saw me. I might have been the young Dungair of seventy years ago, he said. Then we fell talking of those distant years when he had ridden a horse and danced at weddings. He mentioned my grandmother. What was she like as a young woman? I asked him. ‘The handsomest farmer’s wife that ever came to town on market day,’ he said, and I’ll swear that the life burned stronger far down in his sunken eyes. ‘The handsomest wife that ever drove tae market,’ he said. We had buried her two months before on a stormy April afternoon. We had expected few people at the funeral, for we had left Dungair, and the family were scattered beyond the seas, therefore it was a surprise to find how many old men had turned out that day. I thought at the time that they were paying their last respects to Dungair and to the family which, the old woman gone, must now be lost for ever in the great world. I was grateful to the old men in their antique coats, and strangely proud that I had been part of Dungair. But now that I saw that tiny gleam in the old man’s eye, I began to wonder if it were not the pride and beauty of the young wife that had called the old men to her grave after fifty years.

She was the eldest of a family of eight, born to a farmer and his wife in a small farmhouse nearby. Old Sam, her father, was a kind Christian man who helped to build a church after the Disruption and was an elder in it for many years. Beyond a taste for porter he had no faults except that he could neither make money nor keep his wife in order. Kate was the grimmest good woman God ever made, and I say it who feared her from the first day I saw her. She was rigidly Calvinist, of dominating will and devouring ambition—but I will deal with her again. My grandmother inherited her mother’s strength and all her father’s sweetness. As the family were poor she had to work hard in the house all morning and at the herding all afternoon. She liked the herding, for then she used to lie under the shade of a tree reading The Boys of England and enjoying desperate adventures in strange seas. She became more domestic in her reading in later years, and when I knew her she was a faithful but very critical subscriber to the People’s Friend, which, incidentally, is a reason why I have a respect for the work of Annie S. Swan which none of my cultured friends have ever been able to discredit.

She was married when she was twenty, after helping to scrub the pots for her marriage feast. In fact she was still running about the close barefoot half an hour before the minister arrived. She found the home-coming to Dungair a mixed business. There was the matter of a husband with bushy black whiskers and queer brothers, but there was also a blessed freedom after the domination by her mother. She had to take her place as mistress of the farm, and how nobly she did it the old men bore witness at her grave.