Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

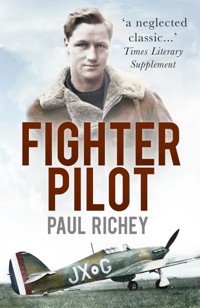

One of 'The 30 Best Travel and Adventure Books of All Time', as selected by Gear Patrol, Winner 2015 US Travel and Adventure website. Fighter Pilot was written from the immediate and unfettered personal journal that 23-year-old Flying Officer Paul Richey began on the day he and No. 1 Squadron landed their Hawker Hurricanes on a grass airfield in France. Originally published in September 1941, it was the first such account of air combat against the Luftwaffe in France in the Second World War, and it struck an immediate chord with a British public enthralled by the exploits of its young airmen. It is the story of a highly skilled group of young volunteer fighter pilots who patrolled, flew and fought at up to 30,000 feet in unheated cockpits, without radar and often from makeshift airfields, and who were finally confronted by the overwhelming might of Hitler's Blitzkreig. It tells how this remarkable squadron adapted its tactics, its aircraft and itself to achieve a brilliant record of combat victories – in spite of the most extreme and testing circumstances. All the thrills, adrenalin rushes and the sheer terror of dog-fighting are here: simply, accurately and movingly described by a young airman discovering for himself the deadly nature of the combat in which he is engaged.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Paul Richey’s FIGHTER PILOT

‘The best-known member of the squadron was to be Paul Richey, whose Fighter Pilot, based on his diaries and published in 1941, was one of the best books ever written about the experience and ethos of air fighting and still rings with unalloyed authenticity.’

Patrick Bishop, Fighter Boys

‘No book published during this war gives a clearer picture of what air fighting is like. The danger, the hardship, the joyous companionship of squadron life on active service, the thrill of victory and the sadness of losses … even at the height of the battle he kept a diary in which he recorded daily details … he has been completely frank.’

Times Literary Supplement

‘There are some things which each member of a people at war ought to know and believe for his soul’s health. This book is one of them. The climax is the writer’s last fight in France – so skilfully told that we seem to share it with him – when he was wounded and shot down.’

Manchester Guardian (26 September 1941)

‘Probably the finest “personal experience” book to have come out of World War II. Detailed accounts of aerial combat and its effect on young inexperienced flyers has the feeling of total immediacy. It is as though he is writing at the moment of battle.’

Manchester Evening News

‘The book [Fighter Pilot] described in a matter of fact way the outstanding work of that small band of British pilots sent to France facing incredible odds whilst Churchill kept most of the pilots – and planes – at home … It sheds light on an aspect of the Second World War in the air often missing from other accounts … it is a mesmerising read. What comes across is the incredible bravery amidst chaos and incompetence in the first days of the war. It gives a riveting account of life in those desperate times.’

Alf Wilkinson, The Historical Association

‘… before the Battle of Britain … was the Battle of France … No better account of that mad period has been written than the book simply entitled Fighter Pilot. It was the work of one of the bravest pilots of them all, Wing Commander Paul Richey DFC.’

Anthony Hern, Evening Standard

‘Une histoire dont le souvenir mérite d’être pieusement conservé.’

Professeur P. Hugon, President, Institut Français de Navigation, in Navigation

‘Ouvrage remarquable … Les Français libres en parlent avec emotion.’

Air Actualites

‘The first and finest story of a fighter pilot in World War II.’

Group Captain Peter Townsend, Paris

‘Richey wrote a deeply human book without the prejudice cherished by so many Britons against their French Allies.’

Wiebren Tabak, Netherlands Ministry of Defence Civilians Monthly

‘A must for any student of fighter tactics … Wing Commander Richey’s classic is copiously illustrated with photos of French, German and British pilots, the machines they flew and the old France that was soon to be swallowed up by Vichy and the Nazis.’

Oxford Times

‘Paul Richey’s experience flying with Number One Squadron in the Battle of France, is a neglected classic …

After Hitler’s Blitzkrieg started on May 10 1940, Richey was shot down three times in nine days. His account of the Hurricanes’ battles with Heinkels and Messerschmitt 110’s thrill with their unfettered immediacy … the tension is remarkable, the writing imbued with desperate urgency … Fighter Pilot has gained in stature over the years … it is a vital record not only in itself, but also in the battle with Hollywood revisionism for the public memory of the war.’

David Vincent, Times Literary Supplement

‘I’ve just finished Fighter Pilot which I am very ashamed to say I have never read before. I’m not just trying to be polite when I say I think it is superb – I think the best book I’ve read by any fighting man. You make the whole thing live …’

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir John Slessor, GCB DSO MC, excerpt from personal letter to Paul Richey, written from RAF Hospital, Wroughton, Swindon (14 February 1970]

‘Our pick of the best books and memoirs onWWII aviation

The literature on the air war during World War II is voluminous … most readers though should find the following titles of interest:-

The war opened in 1939 with the German Blitzkreig on Poland followed by the ‘Sitzkreig’ during the fall and winter of 1939–40, then the assault on Scandinavia, France, the Low Countries and England.

Among the memoirs that cover this period are Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s bittersweet “Flight to Arras” and Paul Richey’s harrowing “Fighter Pilot”, which describe the Fall of France from the perspective of a French aviator/philosopher and a young Royal Air Force pilot thrown into the optimistically named Advanced Air Striking Force in May–June 1940 …’

Richard P. Hallion, ‘World War II: A Reader’s Guide to the Air War’, in Air and Space magazine, Smithsonian Institute, Verville Fellow at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington

‘Richey has an almost cinematic talent for describing the three-dimensional topography of a dogfight, as well as the mixture of terror and exultation that attends it.’

Steven Poole, Guardian

9 St James’s Place

SWl

8 March 1958

My Dear Paul

You might like to know that I have just re-read your ‘Fighter Pilot’ and found it absorbing. Apart from the excitement of your fights you put us in the picture of a very queer period of history. How the Frenchman was out of touch with realism shows up amazingly clearly. As for your own adventures, you certainly had them!

I would like to congratulate you on your successful fights and the successful way you escaped from your failures. I would like to have read more detail of your own exploits but you were set on not saying too much …*

Well, here’s luck!

from

Francis Chichester

I suppose you are in Mexico somewhere, so will ask Mike to pass this on.

[When requesting clearance from Sir Francis’s son, Giles, to publish this letter in The History Press edition of Fighter Pilot, he told me that the time and date of the letter coincided with the great navigator’s crisis in his battle with cancer, making Francis’s opinion all the more poignant and significant. Editor.]

[* Redacted paragraph for personal reasons. Editor.]

To my comradeskilled in action in the battle of France

And in memory of Professor Count Thierry de Martel,who saved Paul Richey’s life on 19 May 1940and took his own life on 14 June 1940

‘It is only with the heart that one can see rightly;

What is essential is invisible to the eye’

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The photographs that supplement this edition were carefully selected by Paul Richey from unpublished contemporaneous photographs from the Etablissements Cinématographique des Armées, Fort d’Ivry, France; the Bundesarchiv, Koblenz, Germany; the Imperial War Museum, London, in addition to photographs from his own and friends’ collections.

My warmest thanks go to these organisations and individuals for their help and generosity. With special gratitude to Emma Bourne for her fine advice and support, and to the team at The History Press – inspiringly led by Michael Leventhal with Chrissy McMorris – for their patience and guidance with this 2016 edition.

Diana Richey

CONTENTS

Praise

Title

Dedication

Quote

Acknowledgements

Map

1. Fighter Command

2. British Expeditionary Force Air Component

3. Advanced Air Striking Force

4.

Entente Cordiale

5. Twitching Noses

6. Battle Stations

7. The Bust-up

8. Action

9. Reaction

10.

Pilote Anglais?

11. ‘

Il Est Fort, Ce Boche!

’

12. ‘Number One Squadron, Sir!’

13. Strategic Withdrawal

14. The Last Battle

15. Paris in Springtime

16. Who’s For Cricket?

Appendices

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

The Author

Postscript 1

Postscript 2

Honours, Awards and Citations

Plates

Copyright

1

FIGHTER COMMAND

I caught my first glimpse of No 1 Squadron in 1937 on a brilliant summer’s day at the annual RAF Display at Hendon. Above a thrilled crowd a flight of four silver-and-red Hawker Furies looped, rolled and stall-turned in faultless unison. They were flown by Flight Lieutenant Teddy Donaldson and Flying Officers Top Boxer, Johnny Walker and Prosser Hanks – 1 Squadron’s formation aerobatic team. They were to go on to the international aerobatic competition at Zurich, where they astonished the Swiss, Italians, French and Germans by taking off in such dirty weather that the other teams refused to fly and performing their normal aerobatic routine with the cloudbase at 200 feet. They won.

Driving back that evening to my RAF flying training school in Lincolnshire, I was impatient for the day when I would be a member of a fighter squadron. Eighteen months later I was posted to 1 Squadron at Tangmere.

During the two years before my posting I had flown over the length and breadth of our kingdom and had come to know and love it as only a pilot can. But Tangmere, between the South Downs and Selsey Bill on the Channel, was a legendary station, not only for its beautiful position, but also for its two outstanding fighter squadrons, 1 and 43.

On arrival at Tangmere I was somewhat alarmed to hear about the ‘flap’ that had swept through the fighter squadrons during the Munich crisis a few months earlier. All the 1 Squadron officers had spent a hectic week in the hangars with the aircraftsmen spraying camouflage paint on the brilliant silver aircraft. The troops had belted ammunition day and night. And the CO of 1 Squadron (which was equipped with obsolete Hawker Fury biplanes carrying two slow-firing machine-guns and capable of a top speed of 220 mph) had announced to his startled pilots: ‘Gentlemen, our aircraft are too slow to catch the German bombers: we must ram them.’

Fortunately for the RAF, England and the world, Mr Chamberlain managed to stave off war for a year. That vital year gave the RAF time to re-equip the regular fighter squadrons with Hurricanes and Spitfires armed with eight rapid-firing machine-guns and capable of an average top speed of 350 mph.

Re-equipment at Tangmere was completed early in 1939. Half the pilots of each squadron now had to be permanently available on the station in case of a German attack. Gone were the carefree days, when we would plunge into the cool blue sea at West Wittering and lie on the warm sand in the sun, or skim over the waters of Chichester Harbour in the squadron’s sailing dinghy, or drive down to the ‘Old Ship’ at Bosham in the evening with the breeze whipping our hair and ‘knock it back’ under the oak rafters. Our days were now spent in our Hurricanes at air drill, air firing, practice battle formations and attacks, dogfighting – and operating under ground control with the new super-secret RDF (later called Radar).

The standard of flying in 1 Squadron was red hot. Johnny Walker and Prosser Hanks, members of the 1937 aerobatic team, were still with the Squadron. Johnny was flight commander of ‘A’ Flight, to which I was posted, and Prosser later took command of ‘B’ Flight. 1 Squadron was one of the last to convert to the Hurricane, and our first object was to de-bunk it as a rather fearsome aircraft. The Air Ministry had forbidden formation aerobatics to be attempted at all, or individual aerobatics below 5,000 feet. 1 Squadron proceeded to demonstrate that the Hurricane could be easily and safely aerobatted both in formation and below 5,000 feet.

Some of our pilots were killed. One dived down a searchlight beam at night and hit the Downs at 400 miles an hour. And I vividly remember, half an hour before I took a Hurricane up for the first time, seeing a sergeant pilot coming in for a forced landing with a cut engine. He was too slow on the final turn and spun into the ground on the edge of the airfield. I was the first to reach him: he had been flung clear, but blood was running out of his ears and he was dying. However, fatal accidents were a fact of flying life, and 1 Squadron’s peace-time average of one per month was considered normal.

During the annual RAF air exercises in midsummer a foreign air force was allowed to fly over England for the first time: French bombers ‘attacked’ London. We intercepted them with the aid of RDF at 14,000 feet in bright sunshine off the south coast. How gay they looked with their red, white and light blue markings! But how pathetically out-of-date. Later that day Johnny Walker and I intercepted three RAF Blenheims low over the Downs under a violent thunderstorm. They looked grim and businesslike, with mock German crosses on their wings …

Shortly after the Exercises we were visited by Squadron Leader Coop, British assistant air attaché in Berlin. He gave us a lecture on the Luftwaffe. We were staggered by the number of superbly equipped German bomber and fighter squadrons. These figures rammed home what a narrow escape England had had at the time of Munich, and as that glorious last summer of 1939 rolled on it became clear that it was no longer a question of whether there would be a war, but merely when it would come.

In August we were told we would soon be leaving for France. Shortly afterwards one of our hangars was stacked with the transport and mobile equipment we would take with us. We heard that several RAF Fairey Battle squadrons had already left and we would be off any moment. And we also heard that Air Marshal ‘Stuffy’ Dowding, Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, was kicking up a stink with the Air Ministry: Dowding strongly objected to surrendering the four fighter squadrons earmarked to go to France with the British Expeditionary Force – 1, 73, 85 and 87. He had even paid us the compliment of stating that he would not hold himself responsible for the defence of London if we were sent abroad.

On 1 September Hitler invaded Poland. On Sunday morning, 3 September, all our officers gathered in the mess at eleven-fifteen to hear Mr Chamberlain’s broadcast to the nation. It was with heavy hearts and grave faces that we heard the sad voice of that man of peace say:

This country is at war with Germany … We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked attack on her people … Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. It is the evil things that we shall be fighting against: brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution. Against them I am certain that right will prevail.

2

BRITISH EXPEDITIONARYFORCE AIR COMPONENT

No 1 Squadron was called to Readiness at dusk on the first night of war. At stand-by in our blacked-out crewroom we sat around talking fitfully or just drowsed. I thoughtfully considered two of the Squadron’s World War I trophies hanging in the gloom near the ceiling: the fins of a Pfalz and a Fokker, both bearing the sinister German black cross.

An intelligence report came in: ‘Heavy concentration of German bombers crossing the Dutch frontier.’ A few minutes later Johnny, Sergeant Soper and I were scrambled and we roared off one by one down the flare-path. Johnny went first, I followed. After I had cleared the airfield hedge, got my wheels up and checked my instruments, I looked for Johnny’s amber formation light, spotted it and climbed after him. Soon I was tucked in beside him, with Soper on the other side, and we climbed up to our patrol height of 20,000 feet and opened out into battle formation.

As we droned up and down between Brighton and Portsmouth we could see the coastline clearly below us under the bright full moon. But the whole country was in darkness. Not a single light showed, in sharp contrast to our previous night flights, with Southampton, Portsmouth, Brighton and every town and village along the coast lit up like Christmas trees.

After an hour on patrol without sighting a German aircraft we were recalled by radio and returned. Another section had been sent off, in spite of ground mist that threatened to blot out the airfield.

Soon after landing we were warned to expect seven RAF Whitley heavy bombers which would land at dawn on their return (it was hoped) from bombing the Ruhr. Only two turned up. We watched them trying to find the airfield in the ground mist and fired off Verey lights to help them. They got down all right and we clustered round them. I noticed a bunch of paper sticking to the tail-wheel of a Whitley and grabbed a handful of it. It was a selection of messages from the British Government to the German people, in German. So that was all they had dropped! The Phoney War was on.

That first week of war at Tangmere was tense. There was no more news of our impending departure for France and our time was spent standing-by our Hurricanes and scrambling at each alarm. We expected to be bombed at any moment, but no bombers came and the tension gave way to a feeling of unreality. It was difficult to realize that we were really at war, and that men were dying in thousands on the Polish frontier while all was peaceful here. The sun shone just the same, the old windmill on the hill looked just the same, the fields and woods and country lanes were just the same. But we were stalked by a feeling of melancholy that resolved into the fact: we are at war. At last, on 7 September, we were ordered to France.

At nine-thirty on the morning of Friday, 8 September, I was snatching a few minutes’ sleep in my room when my batman came in and said: ‘Colonel Richey to see you, Sir’ and in walked my father. I was very glad to see him and we sat and talked of nothing in particular. At ten-thirty my batman dashed in again: ‘No 1 Squadron called to Readiness, Sir!’ I embraced my father and hurried down to the airfield with the other pilots. We were soon grouped beside our Hurricanes. As they were started up one by one, Leak Crusoe took a photograph of the whole team. We ripped the Squadron badges from our overalls (by order) and I gave mine to a fitter to take to my father, who was leaning over the airfield fence watching us. We jumped into our cockpits, and as I taxied past I waved him goodbye. We knew and understood each other’s thoughts. There was no time, or inclination, for more.

We took off in sections of three, joining up, after a brief individual beat-up, into flights of six in sections-astern, then went into aircraft line-astern. Down to Beachy Head for a last look at the cliffs of England, then we turned out across the sea. As we did so Peter Townsend’s voice came over the R/T from Tangmere: ‘Goodbye and good luck from 43 Squadron!’

There was not a cloud in the sky, scarcely a breath of wind on the sea, and the heat in the cockpits was almost unbearable, as we had on all our gear – full uniform, overalls, web equipment, revolver, gas mask slung, and Mae West. Only the almost complete absence of shipping in the Channel brought home to us the fact that there must be a war on somewhere. After about thirty minutes Dieppe appeared through the heat haze and we turned down the coast towards Le Havre.

Our airfield at Havre lay north-west of the town on the edge of 400-foot cliffs. It was new and spacious, with an unfinished hangar on one side. On the other side, surrounded by trees, was a long, low building that turned out to be a convent that had been commandeered to billet us. The Squadron closed in, broke up into flights of six, then sections of three and, after appropriately saluting the town, came in to land individually. We taxied in to a welcome from our troops: No 1 Squadron had arrived in France, the first of the British fighter squadrons to do so.

The evening was spent in the town – the Guillaume Tell, the Normandie, the Grosse Tonne and La Lune following each other in rapid succession. La Lune, I may add, was a brothel, but its main attraction for us was that its drinking amenities were untrammelled by such trifling considerations as time. The town was full of Americans trying to escape from the war zone to the States, and a very cheery lot they were. They were full of admiration for our formation flying; they were full of grog too, and a good time was had by all.

The next day found us sober and very very sorry. Our squadron leader, Bull Halahan, smartly rid us of our hangovers – the next three hours were spent digging a trench in the convent orchard for use in the event of a raid. The sun beat down on our sweating bodies and reeling heads and the alcohol literally poured out of us. At eleven we stopped work – fortunately, as none of us was capable of continuing. Buckets of cold water from the pump pulled us round a little – and then over to the aircraft for a squadron formation.

Soon we were in our cockpits, most of us in shirt-sleeves in the heat. Engine after engine burst into life and was run up by its pilot. The Bull’s order came clearly over the R/T: ‘Come on, we’re off! We’re off!’ He taxied past, followed by Hilly Brown and Leslie Clisby, who formed his section of three. Then came Johnny Walker, Pussy Palmer and Sergeant Soper, the Red Section of ‘A’ Flight, followed by Prosser Hanks, myself and Stratton, the Yellow Section. Next came ‘B’ Flight – Leak Crusoe, Boy Mould, Sergeant Berry (Blue Section), and Billy Drake, Sergeant Clowes and Sergeant Albonico (Green Section).

The fifteen Hurricanes move forward together with a deep roar, slowly at first, then gathering speed. Tails come up, and controls get more ‘feel’. Bump-bump-bump. Almost off. A bit frightening, this take-off. We fly! No … down we come again. Bump … Blast! Must have been a down-draught … Hold it! We’re off now – straight over the cliff edge 400 feet above the sea. I see Prosser shut his eyes in mock terror. It is an odd feeling. As usual, I start to talk to myself. Wheels up. Keep in. Stick between knees. Come on, bloody wheels! Dropping behind a bit. Open your throttle! More! Wide! Ah, there are the two pretty red lights: the wheels are locked up. Now get in closer, for God’s sake! The Bull’s giving it too much throttle, blast him! Anyway – I’m tucked in now. That’s fine.

‘Sections astern – Sections astern – Go!’ over the R/T from the Bull. Back drops my section of three, a little left and underneath. There we are. Don’t waffle, Pussy, or I’ll chew up your tail! Up we climb. Phew, it’s hot! But I’ll bet it looks nice. Hope so anyway.

Out we go over the sea. Flying south I think. Yes, there’s the far side of the Seine. ‘Turning right – turning right a fraction!’ from the Bull. Round and out to sea again. Keep below Prosser in the turn – that’s right. Hell, the sun’s bloody bright! I can’t see Prosser’s wing when he’s above me in the turn. Don’t hit him! Watch his tailplane! The Bull again: ‘Coming out – coming out!’ We straighten. Ah, that’s better – I can see now. And the Bull once more: ‘For Number 5 Attack – Deploy – Go! Sections-line-astern – Go! Number 5 Attack – Go!’

Open out a bit. There goes Johnny. Now Pussy. Soper. Prosser next. Now me. Down I go. Watch ‘B’ Flight and synchronize with them. Pull up now. Fire! Break away quickly. Roll right over and down to the right. Rejoin. Where’s Prosser got to? Can’t see a bloody thing. Ah, there he is, up there. Full throttle! Up – up – cut the corner. Here we come behind him. Throttle back or you’ll pass him. And there we are again, back in line-astern.

Prosser’s waggling his wings. That means form Vic. ‘Re-form! – Re-form!’ from the Bull. ‘Turning right now!’ Towards Havre? Yes, there it is dead ahead. ‘Sections-echelon-starboard – Go!’ Right goes my section. Up. Left. Keep in! There, that’s nice, really nice. The whole squadron is now in Vics of three aircraft and the five Vics are echeloned to starboard. Now, fingers out please 1 Squadron. Hope we don’t overshoot. No, here we go. ‘Peel off – peel off – Go!’ says the Bull. His section banks left in formation beyond the vertical and disappears below. Johnny’s section follows. Don’t watch them – keep your eyes glued to Prosser. Here goes my section now. Down, down we dive in tight Vic, turning slightly left. Keep in – tucked right in! Stratton is OK the other side of Prosser. Right a bit. The controls are bloody stiff – must be doing a good 400. Flattening out now. Don’t waffle! There goes the harbour. Buildings flashing by. We’re nice and low. Keep in! Hold it! Pulling up now – up – over the rise – over the airfield now. Down we go again – just to make the Frogs lie down. Up over the trees – just! Round and back again. Good fun, this. Bet they’re enjoying the show down there. I am! Here we go again, skimming the grass and heading straight for the trees. Pull up – up come our noses and we just clear them. Prosser’s waving his hand. Break away! There goes Stratton’s belly – away we go, nicely timed, in a Prince of Wales, and I’m on my own.

What now? God, I feel ill! Let’s give the old girl a last shake-up. What about an upward roll? Good idea – but watch the others – the air’s full of flying bodies! Let’s climb. Down in that clear space. Need some speed for this. 300-350-360. That’s enough. Adjust the tailwheel. Now back with the stick. Gently up – up – a touch harder now. Horizon gone – look out along the wing. Wait till she’s vertical – now look up. Stick central, now over to the right of the cockpit. Round she goes. Stop. Back with the stick. Look back. There’s the horizon, upside down – stick forward – now over to the left and out we roll. Not bad. Oh my God, I’m going to be sick …

Better land. Throttle right back. Slow down to 160 mph. Wheels down. Now flaps. Turn in now. Open the hood. Hold speed at 90. Tailwheel right back. Over the boundary. Hold off a fraction. Sink, sink – right back now with the stick. Bump, rumble, rumble, rumble – fine. No brakes – plenty of room. Tiny bit heavy that one. Not quite right. Oh well. Taxi in – run the petrol out of the carburettor, switch off ignition, brakes off, undo safety and parachute harness and jump out.

I stroll across to join the other pilots. Prosser fixes me with his characteristic dead-pan look.

‘You just missed a steeple when we were beating up Havre, Paul,’ he says casually.

‘Did I?’ Equally casual. ‘Glad I didn’t see it!’

After lunch we watched 73 Squadron arrive from Digby, in Lincolnshire. They were the other squadron in our Wing, No 67, and were to be our partners for the rest of the campaign in France. And a great bunch of chaps they turned out to be.

Then back to the trench-digging. We were determined to finish the rotten chore before tea, regardless of blistered hands and aching backs. By four we were half-dead, but the trench was practically ready. Just as we were heaving the last agonizing spadefuls out the Bull strode up.

‘OK boys, you won’t be needing that tonight. We leave for Cherbourg in half an hour.’

‘Stone the f—ing crows!’ Clisby, the Australian, neatly summed up our feelings.

Soon we were in the air again, tired and fed-up. It was still hellish hot. Why’s the Bull keeping us in close formation? Ah well – this is 1 Squadron. Cherbourg wasn’t far, although we couldn’t get our hands on any maps and only had hazy ideas of the shape of this region of France. The general opinion was that France turned a corner somewhere hereabouts and continued on down to Spain. However, we found Cherbourg all right – one couldn’t miss it – and having blown the paint off a few boats in the harbour – whose occupants seemed to be enjoying things immensely – we came in and landed individually. The airfield looked big enough, but was actually very short, and I finished up in a skid much too near the fence for comfort. Johnny, of all people, overshot and went round again, which made me feel slightly better.

We dispersed the aircraft along a road and were at once surrounded by groups of French sailors. They were conscripts and showed great interest in our Hurricanes, marvelling at their armament and politely incredulous at their performance figures. This was not surprising, for the only aircraft besides small training machines we saw at Cherbourg were Latécoère dive-bombers – high-wing monoplanes with one 640-horsepower Hispano engine (half the horsepower of a Hurricane), one machine-gun firing through the propeller and another in a rear turret, and carrying two 500 lb bombs, plus the incredible crew of five – pilot, bomb-aimer, gunner, navigator, and engineer! Normal speed was only 80 mph, but right ‘off the clock’ while divebombing. The men who dared dive those ghastly contraptions with that load aboard were worthy of the name.

Refuelling took several hours because of lack of equipment. At last, tired and hungry, we had supper in the officers’ mess and went to bed in a barrack hut. Grey sticky sheets washed in sea-water and straw pillows were incidental, and we were soon sleeping gratefully.

Next day we were up at 5 am on a cold, dark, wet Sunday morning. At six my section was off with the light. Cloud-base was at 200 feet generally, and in patches only 50, so after twenty minutes of futile efforts at reaching our patrol line we trailed back and landed. Soon afterwards we saw through the drizzle in the grey half-light the convoy we were there to protect creeping into port, silent and shadowy as ghosts. Later we learnt that it was the grim advance guard of the BEF – the Royal Army Medical Corps hospital and casualty organization.

Later the clouds broke and the day was spent patrolling. I shall always remember that day flying over the beautiful countryside of Normandy, with its fishing villages in washed-out colours, oyster beds, green woods and fields, and its magnificent châteaux with their round pointed towers and spires and formal gardens.

No enemy aircraft were sighted – we hardly expected any – and soon we were being entertained once more by our French hosts. Conversation was somewhat staccato as only a few of us spoke French. But the most difficult part for us was tactfully to correct the fixed notion that the English drank tea with every meal and on every possible occasion. In this we were only partly successful – they thought we were just being polite. We also found that any attempt to save trouble by refusing anything offered was received as a sign of distaste or disapproval; and to do anything for oneself was regarded as an absolute abuse of hospitality.

Next day, Monday, 11 September, we were ordered to return to Havre after lunch. Having drunk to the success of the Allied cause in our hosts’ best vintage champagne, we took off at two o’clock. We were soon back at our own airfield and happy to see the little convent again.

At Havre we were told that our formation beat-up of the town had been a tremendous success. The whole population had been out in the streets. The cafes and bars had emptied in a trice and the place was a mass of waving, gasping humanity. The town was packed with Americans, and Doc Cross, our MO, who had watched the show with the US Consul and several friends, said the expressions of admiration had become positively embarrassing. They had never seen such flying anywhere and so on and so forth. Eventually poor Cross had crept silently away to hide. But 73 had the last laugh: they went into the town that evening and knocked back the free drinks lined up for us!

On our return from Cherbourg there was little doing for a few days. The time was mostly spent booting a ball about, clambering down the cliff to swim, sleeping, writing letters home or avidly reading the few papers that came across from England by air. Our evenings usually kicked off at about six at the Guillaume Tell, where we sat over Pernods or vermouths watching the life of the boulevards, and ended in the Normandie or elsewhere. We all felt that our first taste of service in France would probably be our last of civilization and peace for a long time and we wanted to make the best of it. I shall always remember Havre with affection – with its fine port, its magnificent view from the hill across to Deauville, its wide boulevards, lively cafes, shops and restaurants – and the church of St Michel, where the old curé preached such a moving sermon to the mothers of France, and afterwards heard my confession, giving me the strength and courage to face whatever was to come.*

We left Havre on 29 September. I was flying a reserve machine without parachute (against regulations) or sights, and had to proceed independently, though within sight of the formation, to avoid risk of collision. I took off first and climbed to 8,000 feet in brilliant sunshine and slight haze. Circling slowly, with difficulty I watched the Squadron leave the airfield and creep out over the sea. I could hear them chattering away on the R/T but completely lost sight of them over land. Coming down to 5,000 feet I picked them out beating up the town in close formation. They looked like a tiny slug crawling over the ground, although they were five sections in sections-astern. After they passed on I came down in a series of loops, rolls and inversions to say goodbye to Havre in general and to one or two people in particular in the only way possible in a fighter. Then I chased off after the Squadron.

I lost them for twenty minutes and got cold feet as I had no maps, but by going down very low I was able to pick them up in the distance against the sky and watched them like a hawk until I had caught them. They broke up over our new airfield at Norrent-Fontes, near St Omer in the Pas-de-Calais, and I circled to await my turn to land. The place looked a mess. There was only one none-too-long run for taking off and landing, and we were accommodated in tents beside the airfield. The first job we did on landing was latrine-digging. And then it began to rain.

* The Havre we loved no longer exists: in 1944, after the Allied victory in Normandy but while the town was still in German hands, it was reluctantly bombed by heavies of RAF Bomber Command at the British Army’s insistence. Owing to a tragic oversight the usual warning to the French underground failed to function, and 8,000 French civilians were killed in the devastation.

3

ADVANCED AIRSTRIKING FORCE

It rained hard for the next two weeks and we did very little flying. The only relief to the monotony was a lecture on what we were supposed to be doing delivered by our air officer commanding, Air Vice-Marshal Blount.

The RAF in France (he told us) was split into two parts.

First, the Air Component of the British Expeditionary Force, comprising four Hurricane fighter squadrons, four Blenheim bomber-reconnaissance squadrons and four Lysander army cooperation squadrons, all based in the Pas-de-Calais. They were to work with the BEF now digging in along the Franco–Belgian frontier and were commanded by Blount himself.

Second, the Advanced Air Striking Force, comprising ten Battle light bomber squadrons based round Reims. They were to work with the French army now holding the Maginot Line along the Franco–German frontier and were commanded by Air Vice-Marshal Playfair.

It was considered that sooner or later (the AOC continued) the Germans would launch an all-out attack on the Western Front and violate the neutrality of Belgium and Luxembourg to break through. In Poland German attacks had been preceded by a thorough air bombardment of all military concentrations, particularly airfields, and this pattern was expected to be repeated.

After the AOC left we fell to discussing his talk. Although the French Air Force was to work with us, we thought we would be taking the brunt of the attack on the British front. Good. We believed our aircraft to be superior to the German machines. Our personnel and training were on the top line, and our morale was more than healthy. We knew the fighting would be tough and continuous and that a lot of us would be killed. Four fighter squadrons to defend the entire British Expeditionary Force! It was absurd. But at least we were not afraid to fight and if necessary to die, and we were confident we would give a good account of ourselves.