1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

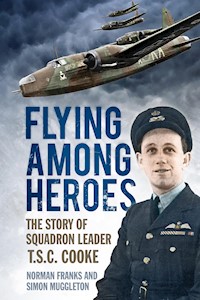

Following the extraordinary career of a Second World War bomber pilot, Flying Among Heroes brings together adventure and human daring with the harsh realities of being a member of the wartime Royal Air Force. Tom Cooke, like hundreds of other young men in 1939, joined up to the RAF just a few days before war began aged 18, being selected for pilot training. Just five years later, he had flown fifty-one operations, taken part in the Berlin bombings and three 1,000-bomber raids, and had even taken part in special operations in conjunction with the SOE. Not only did Cooke volunteer for an optional second and third tour of operations, but he was also shot down over France on his thirteenth special operation, survived the bale out with his crew and evaded capture. Helped by the French Resistance, he managed to make his way into Spain and was taken back to England from Gibraltar. Unsurprisingly, considering Cooke's outstanding bravery and patriotism, he was decorated multiple times in his career. Franks and Muggleton make use of primary documentation, including Cooke's own words, and contemporary images to put together a poignant story of wartime duty. In an effort to portray the situation for many young men like Cooke, much information is included on other squadrons and operations, as well as on Bomber Command itself. In all, 55,000 men of Bomber Command gave their lives to the cause of the Second World War; this is the tale of just one of those remarkable young men who survived the hardships of war, returning victorious to a nation of heroes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

To all the 55,573 airmen lost in the Second World War

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors approached Mr Doug Radcliffe MBE, Secretary of the Bomber Command Association, with a request that a veteran of the association, who had taken part in raids over Europe during the Second World War, write a foreword for this book. Mr Radcliffe, without hesitation, suggested Harry Irons for this task.

Like so many others of his generation he answered the call to arms in 1941 and volunteered to join the Royal Air Force, eventually becoming a sergeant air gunner. During his time, he flew over sixty operations with 9, 77 and 158 Squadrons. He was promoted to warrant officer and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1945. He currently lives in Essex. The authors are grateful for his sincere thoughts and recollections made in this foreword.

The authors are also grateful to both the Bomber Command Association and the artist Philip Jackson CVO for the use of the images used on the back cover of this book. Philip Jackson was commissioned to sculpture seven larger than lifesize figures representing various air crew, to be placed in the Bomber Command Memorial in London. The four images depicted on the cover are: navigator, wireless operator, mid-upper gunner and rear gunner.

Philip Jackson was born in Inverness, Scotland, in 1944, and lives and works in West Sussex. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of British Sculptors in 1989 and has since then undertaken a variety of public commissions which include HM Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother) in the Mall, London; the Falklands War Sculpture in Portsmouth; and the 1966 World Cup Sculpture at Newham. He was made a Companion of the Victorian Order (CVO) in the Birthday Honour’s List in 2009.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Warrant Officer Harry Irons DFC RAFVR

Introduction

Preface

1A Flying Life for Me

2Operational – First Tour

3Aircraft Captain

4On Rest – Instructing

5Back on Ops – Second Tour

6Press on Regardless

7Reflections

8Rest & Return – Third Tour

9The Final Missions

10Evasion

11Après la Guerre

Appendix ARecord of Service and Aircraft Flown

Appendix BTom Cooke’s Operational Flights

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD

BY WARRANT OFFICER HARRY IRONS DFC RAFVR

At the cessation of hostilities in 1945, and while awaiting demobilisation, the relieved surviving air crews of Bomber Command were aware of the past years, their squadron, the stations, runways, flare paths, but most of all, the comrades they had left behind who had lost their lives.

Most of us had no knowledge of the actual 55,573 lost in the conflict until much later. In the aftermath of the Second World War the press started to disclose other figures that had been kept secret from the public during the war. We were told of the Holocaust and shown graphic pictures, the bleak Russian campaign, the treatment of prisoners of war in the Far East, the forced marches: victory came at a cost.

We awaited the Victory Parade with pride, but we were dismayed at the contents of the prime minister’s victory speech. There was no mention made to the nation and the Commonwealth of Bomber Command’s contribution to victory. No individual campaign medal for the air crews or ground crew to those fortunate enough to have volunteered and survived. High-level protests made no difference, Bomber Command veterans were just left with the words ‘Dresden’ ringing in our ears.

How about our comrades who had gone before?

The blue priority telegram or a letter from a sympathetic CO or overworked adjutant was the only thing a grieving family had for the loss of a son, husband or brother. It took many years before the Air Ministry, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the Red Cross were able to provide some small amounts of information to the bereaved.

Some 20,000 airmen from the Commonwealth and parts of occupied Europe who flew with the RAF and had no known grave were later to be recorded on the tablets of a memorial at Runnymede, close to Windsor.

Over the past sixty years, several attempts have been made to the various authorities to amend the decision not to grant air crew and ground crews of the RAF a campaign medal; one such application even reached the House of Commons, but to no avail.

Some of the air crews who flew after D-Day (6 June 1944) were granted the France and Germany Star, but it had no association with flying; indeed, it was given to members of all the armed forces and the Merchant Service who took part in that campaign.

Prior to D-Day, air crew received the Air Crew Europe Star if they fulfilled the necessary conditions, but this was not given exclusively to Bomber Command members.

Serving on the committee of the Bomber Command Association, I became aware of a growing demand from the membership to raise funds for a fitting memorial to commemorate those 55,573 young men who freely volunteered to fly against the Nazi onslaught and were sadly killed in action.

The Heritage Foundation, chaired by Mr David Graham along with their president, Mr Robin Gibb CBE of the Bee Gees, shared these same thoughts, and initiated a fundraising project in 2008, backed by the Daily Telegraph newspaper. The public reacted overnight, and funds came rolling in over the following years, mostly from bereaved relatives. The queen’s sculptor, Philip Jackson CVO, was commissioned to mould seven larger than lifesize figures in bronze representing the various trades of air crew, which were to be placed in the centre of the memorial. This memorial will now finally be unveiled on 28 June 2012 in Green Park, Piccadilly, London.

When Doug Radcliffe MBE, the secretary of the Bomber Command Association, approached me to write this foreword I said, ‘Why me?’ He replied, ‘Read the title Harry, get airborne again.’

After sitting in the rear turret as an air gunner for many hours during the two tours of operations I completed over Germany, France and Italy, being on the top deck of a London bus is high enough for me these days.

However, I took note of the title and received my copy from Doug Radcliffe, who had virtually read it overnight and commented to me what a good read it was. It took me a whole week, for I didn’t just read it, I made a complete study of it. With my flying log book by my side, I compared my trips against those of Squadron Leader Tom Cooke and his crew, and wonder how they survived. I am sure many other air crew of the Second World War, students and authors will also do the same.

Over the years following the Second World War, veterans of Bomber Command have tried to move away from the word ‘hero’ – what on earth does it mean anyway? Surely Tom Cooke and his navigator Reg Lewis would shy away from the dictionary explanation: ‘a man of distinguished valour or performance’. Man can do heroic things, but it leaves him short of being a hero.

Reg Lewis was a very good friend of mine; we were near neighbours and worked together over many years with the Bomber Command Association. Reading this book about his wartime pilot, I found out many things that Reg had never mentioned to me about his time in the RAF. I am sure he would have laughed at the mention of the word hero, but to me he was a hero.

Heroes – maybe it’s not me, but others. This book really pulls out the difference; it enabled me to compare many of the sixty operations shown in my log book with those experienced by Tom Cooke and his crew. Could it be that when Squadron Leader Cooke was over the Ruhr at the controls of his Stirling, I was sitting in the rear turret of my Lancaster some 5,000ft higher looking at the same target? Glancing through the entries in my log book for 1942 and 1943, they certainly match, and I’m sure other veterans reading this book will do the same. Tom Cooke’s recollections of his ‘ops’ are so clear and vivid, with them being well explained in the text.

Training in the RAF was a time to remember; the book boldly points out that air crew, having received the protective rank of sergeant along with the elusive but very proud brevet worn on the uniform, were often at variance with the long-serving sergeants. We were derisively called ‘overnight NCOs’, little thought being given that we could also ‘disappear’ overnight.

Looking back, waiting to get my stripes, it took the powers that be just seven weeks to train me as an air gunner – there was no time to fit in an operational training unit, no adapting to the squadron aircraft or turret, just an evening over Düsseldorf!

Come the autumn of 1943, Bomber Command continued their nightly attacks on chosen targets, while the American 8th Air Force, growing in strength and in spite of losing many of their experienced crews, challenged the Luftwaffe in daylight flying operations.

It was about this time that Squadron Leader Cooke added the Distinguished Flying Cross to his other decorations and set his sights on another challenge that only a few other crews in Bomber Command would engage in. He and his chosen crew opted to fly with 138 Squadron out of RAF Tempsford, working with the Special Operations Executive, dropping secret agents into enemy-occupied territory. Tom and his crew would be carrying these agents instead of bombs, and known only to him by their code names, such as ‘Roger’. These agents would link up with the Resistance groups and wreak just as much damage and destruction as any stick of bombs could. So now, Tom Cooke and his crew would find themselves flying over France, Germany, Norway, Poland and Italy dropping supplies to the underground, as well as the agents. Their story is well told here.

In the summer of 2009, I joined Reg Lewis and others of the Bomber Command Committee for a fundraising event at Lord’s Cricket Ground. The ground had been an Air Crew Recruiting Centre during the war and was a fitting place to watch England take on Australia.

Whilst that match was in full swing a Lancaster aircraft flew over, stopping play – what a salute to heroes, long gone.

INTRODUCTION

As this book was written the construction of the Bomber Command Memorial in the north-west corner of London’s Green Park, and in close proximity to the Royal Air Force Club, Piccadilly, is under way.

For many years after the end of the Second World War, its most distinguished leader, Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris GCB OBE AFC LL.D, who died in April 1984, wanted some tangible recognition for all air-crew members who had flown with his Command during the war. He felt a suitable campaign medal should be struck, for he genuinely felt that his chaps had performed magnificently throughout the five-year campaign against the Axis powers of Germany and Italy.

He knew too that of some 125,000 such men from Britain and the Commonwealth, as well as from European countries overrun by the Germans such as Norway, France, Belgium, Poland and Czechoslovakia, a total of 55,573 had been lost. However, Harris’ campaign to have such a medal failed, it being said that having the Air Crew Europe Star or the France and Germany Star was adequate recognition for those who had seen active duty within the ranks of Bomber Command.

During those wartime years Bomber Command had lost an estimated 8,325 bomber aircraft during over 365,000 sorties from its 128 airfields spread across the United Kingdom. In addition, 8,403 men had been wounded, while another 9,338 had been brought down and taken prisoner. The average age of a Bomber Command air crew was said to be just 22, and all of them were volunteers. Nobody who joined the Royal Air Force for wartime duty could be made to fly against the enemy, but, of course, there was never any shortage of volunteers.

Sir Arthur would have been very proud if he had known that in recent years there has been another campaign in existence, that of battling to have a permanent memorial built to commemorate the sacrifices of Bomber Command air crew. Not many years ago a few famous men got together to form a committee to see if such a memorial could be built. They were John Caudwell, Lord Ashcroft KCMG, Richard Desmond and Robin Gibb CBE.

Other than choosing a site for such a memorial, the cost also needed to be addressed. Donations came from many people and places, and public subscriptions were also welcome. By 2011 almost £6 million had been raised and the project was on. The RAF Bomber Command Memorial Fundraising Committee, headed by pop star Jim Dooley of the famous Dooleys and the President of the Heritage Foundation, Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees, worked tirelessly. The committee was supported by the Daily Telegraph newspaper and, with the Daily Express, that has helped to raise awareness of the project; the response of the general public was, and continues to be, amazing.

Once the project could be seen to be moving in the right direction and a location found, Mr Liam O’Connor, who had previously designed the Armed Forces Memorial in Staffordshire, was asked to put forward a design for the Bomber Command Memorial, which he has done magnificently. The memorial will feature as its centrepiece a 9ft-high bronze sculpture by Philip Jackson, depicting seven men of a heavy bomber crew after returning to their base from an operation.

The lead contractor is Gilbert-Ash NI Ltd, a building and civil engineering contractor based in Northern Ireland. This company is well known for its ability to build difficult and complex projects in a flexible manner. Contracted for the stonework is S. McConnell and Sons, another well-known company here and throughout the world. All this was agreed after careful negotiations between Westminster City Council, the Royal Parks and the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund. Once completed, the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund will take ownership and be responsible for future maintenance of the structure.

On 4 May 2011, a foundation stone was laid during a ceremony on the site of the proposed memorial. In attendance was a group of distinguished men, led by the Duke of Gloucester and in the presence of the Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir Michael Beetham, himself a wartime Avro Lancaster pilot, and the President of the Bomber Command Association. Guests included Lord Craig, who represented the RAF Benevolent Fund, and of course Robin Gibb, John Caudwell, Lord Ashcroft and Richard Desmond. A service was conducted by the Venerable (Air-Vice Marshal) Ray Pentland, chaplain-in-chief of the RAF, and included a reading by Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton, Chief of Air Staff.

Others in attendance were the Right Honourable Andrew Robathan, Minister for Defence Personnel, Councillor Alan Bradley of the Welfare and Veterans Organisation, sculptor Philip Jackson and the architect Liam O’Connor. The service ended with a flypast by the Battle of Britain Memorial flight’s Avro Lancaster bomber.

The memorial is due for completion in 2012 and hopefully will be unveiled in June.

***

Just a few years ago I was asked to prepare a list of all those men and women who served in Coastal Command in the Second World War to be recorded within the pages of a permanent Book of Remembrance. It was a daunting task for there were over 4,000 of them, tiny in comparison with Bomber Command’s 55,573, but nevertheless a huge task.

Thanks to help received from the Air Historical Branch, then in London, and the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, I had access to the huge lists of members of the Royal Air Force who had been killed, by whatever means, during the Second World War. It took me several months to trawl through more than two dozen boxes, filled with flimsy horizontal foolscap pages that, from memory, each recorded more than a dozen casualties, giving name, rank, number, command, squadron or unit, date of loss, where lost and where buried (if known).

It became apparent that every loss of life that befell the RAF, in all Commands and in all theatres, whether killed in action or died of a burst appendix, was there. Once the Coastal Command losses were extracted, compiled and typed up, the computer disc was given to a printer who produced several tomes. The main one would be presented to Westminster Abbey for display, a page being turned each day. In due course it was unveiled by Her Majesty the Queen in the presence of a number of former Coastal Command dignitaries.

I only mention this because I should not like to be given the task of doing something similar for Bomber Command’s losses, which, if every other serving man and woman in the Command who died in other ways between 1939 and 1945 were listed, would no doubt reach nearer 60,000 than the 55,000 usually noted as lost on operations. War is an appalling blot on humanity but it is something mankind has lived with since the dawn of time and no doubt will continue in the years to come. However, it does generally bring out the best of the brave, the most courageous, the most dogged, and can forge a man’s ability to overcome the many trials and tribulations thrown at him.

The subject of this book was just an ordinary sort of chap, nothing special, born into a normal loving family, yet when faced with the need to help defend his country and his country’s way of life, willingly came forward to do his bit. Fortunately he was able to do more than his bit and survived to continue a life of peace, but on more than one occasion he risked his life in the often fatal struggle that is war. He was not found wanting.

Millions of men face these and other dangers in wartime, but it seems to me that the flying man, by which I mean the flying man based in Britain during the Second World War, suffered a very different war to his counterparts in the navy or in the army. Other than when home on leave or on some sort of defence duty in Britain, the sailor is at sea, and the soldier can be in any number of hostile places overseas. They lived with the constant danger of being put in harm’s way, whether in a naval action in the middle of an ocean or in a trench somewhere in North Africa, Burma or later on the Continent. In some ways they were fortunate, for they each knew that they had to survive the constant danger during whatever conflict they were engaged with before going home.

The airman, however, whether in Fighter, Coastal or Bomber Commands flying from Britain, faced danger for perhaps minutes, and often hours, but when they had returned to their airfields – if they returned – their world changed to a very civilian sort of existence. They could sleep between sheets in a bed; they could eat as well as wartime rationing allowed; they could go to the local pub or cinema; meet a girlfriend or occasionally go home on leave to a wife or mother and see their old pals. It must have been a constant shock to the system to be one minute in the hell of searchlights, flak and enemy fighters over a German city, and shortly afterwards downing a pint of bitter in a pub. That night they would crawl into a warm bed and with luck sleep soundly, but they knew that it would not be many hours before they were back in hell once more. Also, of course, the majority of them had still been at school when the war began, each contemplating a life far removed from flying over a hostile country where they were the target. We may possibly look at a veteran airman and think how brave he had been, how heroic, yet only a year or so earlier he had been nothing more than a civilian, wanting civilian things, like a good job, a wife, perhaps children. All that changed in September 1939.

Bomber Command air crew, flying a tour of thirty operations, faced this enigma of life every day. Thirty times over a few months, perhaps more than thirty, they would assemble in the flight hut, their stomachs in a knot but trying to stay calm and casual, but waiting for that night’s target to be revealed. Was it Berlin? Was it only over to France? Perhaps only a mine-laying trip? Each represented a degree of danger that each man assessed personally, although it was clear that an easy raid could end in death just as surely as a long, hard one. It was the luck of the draw. There was just that little loosening of that knot in the stomach if the target looked a little easier.

If they survived and got home, they almost dreamt their way through debriefing, hardly noticing the tea and sandwiches waiting for them, then staggered off to find either their room in the mess or the cot in some Nissen hut, and they could then hope for a few hours of oblivion. The next day it would begin all over again, and all they could be thankful for was that the tour was at least one trip less than previously. No doubt they would often ask themselves why they were doing this. However, deep down they all knew why – it was their duty.

After the war Albert Speer, Germany’s Minister of Armament, wrote: ‘The strategic bombing of Germany was the greatest lost battle for Germany of the whole war. Greater than all their losses in all their retreats from Russia, or in the surrender of their armies at Stalingrad.’

Norman Franks

East Sussex

March 2012

PREFACE

RAF Tempsford, situated along the A1 east of Bedford and south of St Neots, was the home of 138 Special Duties Squadron, and had been since March 1942. Its equipment ranged from Westland Lysanders to Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys, to Handley Page Halifaxes, and the men who flew them or in them carried out a more or less secret, cloak-and-dagger war, transporting Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents or dropping supplies or arms and other equipment to partisan units. They ranged as far north as Norway or south-east to Yugoslavia and Poland, as well as France, Holland and Belgium.

In the early days Lysander pilots flew clandestine operations into the occupied territories of northern Europe, landing in fields or on open ground at night, delivering agents or on occasion collecting other agents, and sometimes escaping prisoners of war, back to England. As it became necessary to deliver arms, explosives, radio equipment and so on to Resistance workers or partisan bands, heavier aircraft were needed, so Whitleys began to be employed once they were no longer being used in the bomber role. These in time were replaced by Halifax bombers, even operating from North Africa when the Halifax crews flew a mission across Europe and over the Mediterranean, and from there returned to England over a similar route, dropping supplies to Resistance groups in southern France.

By February 1944, the squadron’s Halifax bombers, under the command of Wing Commander R.D. Speare DFC, were the norm for dropping supplies and parachuting agents into these same occupied territories rather than risk landing in darkened countryside. Richard Speare was an experienced bomber man, having won his DFC with 7 Squadron in 1941, and a Bar while with 460 Squadron RAAF in 1943. Everyone was expecting an invasion of northern Europe to take place sometime during 1944, so as the time grew nearer to the planned D-Day, more and more Resistance fighters were being prepared and supported by Britain’s SOE, and 138 Squadron’s air crews were being kept busy.

On the night of 7/8 February 1944, four of 138 Squadron’s aircraft took off for operations over France. At 2252hrs, Flight Lieutenant Downes took off in Halifax ‘D’ on Operation Dacre 1/Harry 18, carrying an agent, packages and supplies. The mission was a success and the agent and supplies were safely parachuted down into France. At 2302hrs, Wing Commander Speare took Halifax ‘J’ off on Operation Harry 17, carrying an agent, supply containers and packages, but it was not successful as no recognition signals were received from the ground, so the mission had to be abandoned. Another crew, on a similar operation coded John 35, led by Flying Officer G.D. Carroll in LL114 NF-F, was lost over France, coming down at Autrans, west of Grenoble. None of the crew survived.

The third Halifax on this night’s roster was LW275 O for Oboe, which went off at 1945hrs with Squadron Leader T.C.S. Cooke DFC AFC DFM AE at the controls on a Jockey 5 sortie. It was to be a long trip, 700 miles or further, as the agent was going to bale out near Marseille. Cooke’s crew consisted of:

Flying Officer R.W. Lewis DFC

Navigator

Flying Officer L.J. Gornall

Flight Engineer

Pilot Officer E. Bell

Bomb Aimer

Flying Officer J.S. Reed

Wireless Operator/Air Gunner (WOp/AG)

Flying Officer A.B. Withecombe

Dispatcher

Flying Officer R.L. Beattie RCAF

Rear Gunner

It was Thomas Cooke’s sixty-third operational sortie, and it was later noted that his experienced crew had between them a combined total of 291 missions. For Reg Lewis this was his forty-first operation, having been with Tom Cooke’s crew in 214 Squadron, while Len Gornall was on his forty-eighth.

We are lucky with this story, because not only do we have Squadron Leader Cooke’s flying log books and squadron operational records to refer to, but we also have a recorded interview by him, conducted by the Imperial War Museum archivists in the 1980s, together with a similar one recorded by his navigator, Reg Lewis DFC.1 The museum have been gracious enough to allow us to make use of these spoken words which appear here in the text in various chapters. Thomas Cooke was later to relate on his tape:

When we delivered agents we were usually flying at 250 feet, and that was the altitude we flew at this night and it was important not to fly over any defended sites. On this trip, as we were going out, we made a mistake. Something went wrong and we went over a defended area near the French coast and were shot up. All seemed to be well, however, so we carried on to carry out what we had been briefed to do. We got well into France and then the starboard-inner engine suddenly caught fire. It started to glow and this glow began to get bigger and bigger, and in the end I had to order everyone to bale out.

Whether or not the engine had been damaged by the anti-aircraft (AA) fire is not clear. The weather had deteriorated a good deal and after taking off cloud prevented any sign of the ground until they baled out over France. He continued:

I went down to get out of the lower escape hatch but found it was jammed, so I came back to the cockpit and looking out I could see we were in a spiral and decided to try and fly it down. However, the wing then became a mass of flames and the altimeter was spinning round, so I struggled back down to the hatch and managed to beat it open, and baled out.

Len Gornall believed they had suffered a cracked carburettor as all the temperature and pressure gauges were showing normal on his engineer’s panel. However, with reduced power they were losing height and they were also beginning to ice up. Eventually it became impossible to maintain height so the order came to get out.

Cooke continued:

I landed somewhere between Dijon, towards Valence or perhaps Lyons – right in open country. The main problem was initially to try and find out exactly where we were. I say we because I had met up with my flight engineer and mid-upper gunner [and dispatcher]. We had some maps, but the sky was cloudy so there was no way we could look at the stars to get our bearings. We found some signposts that at this time had not been taken down, but they didn’t mean much to us. Unless you have pinpointed the area they don’t mean a thing, and they certainly did not show us the name of any town we could recognise or locate on our maps.

I decided our best bet was to go round and come up underneath the border of Switzerland because we knew the border at a place called Jura was heavily guarded and there was no way we could get across there. So we tried to edge round and come up to Grenoble, then up to the southern part of Geneva. The first thing that struck me when I had started with 138 Squadron, was that France seemed to be full of people who would assist us if shot down. Being a flight commander I was one of the few people that saw a secret map of France with all the dropping zones for our agents, so the impression I had was that France was an absolute maze of people wanting to help us. I don’t think the other two were really aware of this, certainly Gornell wasn’t, in fact he wasn’t really sure of what time of day it was. He wasn’t my earlier flight engineer, although I had known him for some time.

So we decided to start knocking on doors, and as I was the only one who spoke any French, it fell to me to say that we were English airmen and could they help us. The usual answer was to have the door slammed in our faces, and on the one or two occasions when I was asked to ‘come in’ I felt uneasy, in case someone was sent along to the local gendarmerie, so we did not hang around long. Eventually we came into contact with somebody who put us in touch with someone in a village called Beaurepaire and although helpful, they put us in contact with who they thought were the Maquis but who turned out to be FTP (Franco Tireurs Partisans) – who were communists.2

They sheltered us but were doing odd little sorties, and being able to speak French I understood what was going on. The first time they went out they crashed into a farmhouse, bullied the occupants and all they did was to pinch cigarettes and bread, etc. After a while I asked them why they didn’t go out and raid a few bridges or something, but that wasn’t very popular with them.

After a period of time, the agent that we had bundled out of the Halifax before we crashed, Lieutenant Cammaerts – although of course we only knew him then by his code name of ‘Roger’ – turned up, and spoke to this lot, and then he quickly passed us along to somebody else and we finished up with a Monsieur Merle at Valence, right by Valence airfield. He was a great old guy aged 85. He put us in a room at one end of his house while at the other end he was entertaining Germans because they brought him food which he then shared with us! When we eventually left he asked me to drop him a machine gun, but I said that it would not be a good idea but I would try and drop him some coffee if I could, knowing full well that was never going to happen. All I hoped now was that he were going to evade successfully and get home. But would we?

Thomas Cooke’s war had travelled a long way since joining the RAF in 1939. He had done a lot of flying and had flown many dangerous bombing operations. It is ironic that his last squadron had been working in co-operation with the French Resistance organisations and now, here he was starting to be helped by those same people in an attempt to get him and his companions home.

Notes

1Anyone interested in hearing these tapes should contact the IWM at Lambeth. They are to be located under recording numbers 9794 (Lewis) and 10079 (Cooke).

2The FTP was part of the French Communist Party (PFC), who took the name from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which literally meant ‘Free Shooters’ or Irregular Corps of Riflemen.

1

A FLYING LIFE FOR ME

Most biographies begin with a birth, so we will start there too. Thomas Charles Seymour Cooke was born in Southsea, Portsmouth, in the borough of Buckland, Hampshire, on 23 July 1921, the only son of Mr and Mrs Herbert Seymour Cooke, previously of Heston’s Post Office, Alconbury, just north of Huntingdon. He attended St John’s School and College in Grove Road, Southsea, from 1932 until 1938, and acquired the nickname ‘Bunny’. In 1938 he acquired the Oxford University General School Certificate.

Upon leaving full-time education he became a junior clerk in the Portsmouth Rates and Electricity Department. As Thomas Cooke later recalled:

Before the war I wanted to take a short-service commission in the Royal Air Force and my father wanted me to join him in business. This was about the time of the Munich crisis. We reached a compromise, he said why didn’t I join the RAF Volunteer Reserve and at the same time I’d be able to do my flying while working full time with him in the business. So I joined the RAFVR, initially in Southampton and later in Portsmouth Town Centre.

Unfortunately it is not clear what his father’s business was, but Cooke clearly stated in his RAF personal details that he worked as a council clerk. His home address was 221 St Augustine’s Road, Southsea, and while he mentions Southampton and then Portsmouth, Southampton was no doubt where he went into a recruiting office, for his date of enlistment is given as 25 August 1939, for a period of five years. While he may well have wanted to join the RAFVR after leaving school, he obviously did little in the way of taking to the air, for his service commenced on 25 August as 758091 AC2 U/T (aircraftsman second class, under training), and his call up came the day after Germany invaded Poland, 2 September 1939. He is shown as being 5ft 11in tall, chest measurement 35in, with fair hair, blue eyes and a fair complexion. In other words, he was quite average. By this time he had been elevated to the rank of sergeant (sgt), that is, sergeant pilot U/T.

I have to say I was delighted when the declaration of war came. I’d been interested in aircraft since the age of seven and people like Billy Bishop, von Richthofen, Roy Brown, etc., were extremely well known to me. This, with my interest in flying, I had a burning desire to emulate such men, so when war broke out, like all my fellow reservists down at Portsmouth, we were all very interested. We were of course all fully aware of the political situation and what we were about to lose if Hitler was allowed to go on his merry way, so there was that aspect of it. So although we were all young men, we seemed very mature, viz-a-viz, what we were doing and what we were going to fight for.

***

While it seems that Tom Cooke would have been delighted to follow and hopefully emulate his First World War flying heroes, they were all distinguished fighter aces. We have no idea how he felt once he began to realise that the RAF had other plans for him – to become a bomber pilot.

By these early days of the war, elements of Bomber Command were already in France, with Bristol Blenheim Is and Fairey Battles, both light bombers, of the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) and the Air Component both supporting the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Not that they would amount to much as bombing aircraft, but the crews were keen to show their mettle in an air war as part of Bomber Command.

While Tom Cooke was starting to feel his way about the service, he and his fellow trainee airmen could never guess how long the war would take to be won, or how many of their fellow Bomber Command brothers would not live to see victory. Already the first deaths in the Command’s air war had occurred. On the first night of the war, 3/4 September 1939, two Wellington bombers from 9 Squadron of RAF Honington and five Blenheims of 107 Squadron, based at RAF Wattisham, failed to return from Wilhelmshaven. The targets for a small force of Blenheims and Wellingtons were German warships at Wilhelmshaven and Brunsbüttel, the British not wanting to bomb German land targets at this early stage. In the event most of the aircraft crews failed to find their targets due to low cloud but some attacked warships at Wilhelmshaven.

It was a salutary lesson for everyone when it was learnt that seven aircraft had been lost. Of the twenty-six air-crew members lost, only two survived as prisoners. All the rest were killed. They would be followed by over 55,000 Bomber Command members before the war would be won.

The two captured airmen were Sgt G.F. Booth and Aircraftman First Class (AC1) L.J. Slattery, observer and air gunner to Sgt A.S. Prince, one of the Blenheim pilots. Larry Slattery became the first Bomber Command airman to be taken prisoner, Booth a close second. Author Norman Franks met Larry Slattery in the mid-1960s, living near to each other in south London. Larry had been invited to the first showing in a Wimbledon cinema of the film The Great Escape. Talking to him, Franks became aware of a very humble man who had borne his six years as a prisoner with much stoicism and not a little fatalism. In these early days many light bomber crews were made up of AC1 or even AC2 airmen who volunteered to be air gunners, so he and others began their captivity with the lowest rank of air crew. Those that lasted a few weeks received the insignia of the flying bullet to wear on their sleeves. This was a brass bullet design with wings spreading out from either side. It was later replaced by a winged brevet with the letters ‘AG’ in the centre. In 1940 all air crew below officer rank were given the rank of sergeant and, as Tom Cooke will relate, this was not always popular with the ‘old sweats’ who had won their three stripes after many years of service, both in England and abroad.

Larry Slattery would end up in the prison camp at Kopernikus and eventually became a warrant officer. G.F. Booth was with him, also becoming a warrant officer, so at least they had each other for company. They would have been extremely surprised if they had known how many other British and Commonwealth airmen would join them or be placed in other camps before the war ended.

***

Like most young men of the day, Tom Cooke had to wait for things to happen and it was exactly one month before he received his first posting to No.31 Training Wing, where he underwent all the necessary instruction about the RAF, its history, how to march, how to salute etc., and what he might expect to happen if he showed the necessary personality to continue in the service. He passed, and on 11 December was shown as being attached to No.3 ITW (Initial Training Wing) at Hastings, Sussex, and eleven days later was sent to No.12 EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School), where at last he would see an aeroplane close up.

No.12 EFTS was at Prestwick in Scotland and he arrived to be taken under the wing of Flight Lieutenant (F/Lt) I.G. Statham RAFVR, his flight commander (‘B’ Flight). Ivan Statham handed him over to F/Lt D.E. Turner, who was to be his initial flight instructor. In the meantime, Tom Cooke needed to settle in, and as far as the regular RAF NCOs were concerned, it wasn’t going to be too easy for him. His first clash with reality came once he and the others arrived at Prestwick. He knew there was going to be some sort of social upheaval but not to what degree:

We reservists were all sorted out and sent to our various training schools, mine being Prestwick, which was in those days just a 400-yard square field, and we were billeted out. From there I went to Sealand and it was there we first noticed that the Sergeants’ Mess was crowded and we weren’t the most popular fellows because these chaps who had been working away for 12 or more years in the Service to become a sergeant, suddenly found they’d been invaded by chaps who had been made sergeants overnight. This had also been felt, although less pointedly, at Prestwick. These sergeants found we were crowding their Mess and making things very uncomfortable for them, so they weren’t exactly delighted to see us.

They tried, and in fact did, exclude us from their Mess and we then had to live in empty married quarters at Sealand. They were beginning to make special catering arrangements for us, but this didn’t affect me because I left before they brought it in.

Cooke got his first taste of being a pilot on 12 December 1939. F/Lt Turner took him over to the RAF’s most popular and well-known ab initio training aeroplane, the de Havilland Tiger Moth, a two-seater biplane. Turner showed him round N6614, talked to him about the cockpit layout, the instruments, controls and ailerons, elevators and rudder. Then he got Cooke seated and they took off for a forty-five-minute flight, noted as an ‘air experience’ flight, again showing him the controls, what they did, and generally flew around the locality in straight and level flight without anything fancy. Turner would have no way of knowing if this youngster in the other cockpit would enjoy the experience – or throw up!

Shortly after this, Turner showed him how to taxi an aeroplane, then again took off, flying straight and level once more but doing some climbing, gliding and even stalling the machine to impress upon his student the dangers of losing forward flying speed and how to recover. Two more trips the next day covered the ground again, but included some medium turns, landings, taking off into wind, glide approaches and so on. Two similar flights took place on the 14th and 15th, each flight lasting around forty to fifty minutes.

Spinning took place on the 18th, Turner obviously less troubled by his new man’s airsickness probabilities, and these training sessions continued in the cold December skies until the 22nd. On this day, after an initial forty-five-minute trip, now flying N5444, Turner told the chief flying instructor that Cooke was ready for his first solo. F/Lt R. Hanson took Cooke up for a pre-solo test for half an hour and was obviously happy to let the youngster go solo. Climbing out of the Tiger Moth, he told Cooke to take off, fly one circuit and land without breaking anything. Cooke complied, and his ten-minute flight brought his total flying hours to a nice round ten.

***