Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

On the night of 4 April 1793, two lovers were preparing to compel a cleric to perform a secret ceremony. The wedding of the sixth son of King George III to the daughter of the Earl of Dunmore would not only be concealed – it would also be illegal. Lady Augusta Murray had known Prince Augustus Frederick for only three months but they had already fallen deeply in love and were desperate to be married. However, the Royal Marriages Act forbade such a union without the King's permission and going ahead with the ceremony would change Augusta's life forever. From a beautiful socialite she became a social pariah; her children were declared illegitimate and her family was scorned. In Forbidden Wife Julia Abel Smith uses material from the Royal Archives and the Dunmore family papers to create a dramatic biography set in the reigns of Kings George III and IV against the background of the American and French Revolutions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 499

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FORBIDDEN WIFE

About the Author

Julia Abel Smith has a degree in History of Art from Cambridge University. She has worked for Art UK and The Landmark Trust. While researching the history of one of the Trust’s follies, The Pineapple at Dunmore, she discovered Lady Augusta and was captivated. Julia has written for Country Life and House & Garden magazines and is the author of Augusta’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. She lives in Essex.

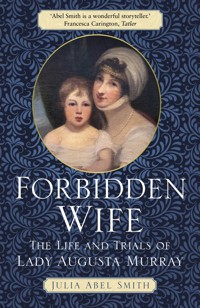

Cover image: Lady Augusta Murray with her son Augustus. (By kind permission of DACOR Bacon House, Washington)

First published 2020

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Julia Abel Smith, 2020, 2022

The right of Julia Abel Smith to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 451 4

Typesetting by Geethik Technologies

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

In memory of

Charlotte Haslam,

Landmark Trust Historian, colleague and friend

1954–97

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to list the many people who have helped me in the preparation of this book. First, I acknowledge with sincere gratitude the permission of the late Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to make use of the relevant material in the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle.

I am deeply indebted to Anne Dunmore, initially for allowing me to look at her family papers, and subsequently for taking such an interest in the project. Her support has been invaluable.

Tessa Spencer at the National Register of Archives of Scotland helped me to find the Hamilton and Adam family papers and I am grateful to the Duke of Hamilton and Keith Adam for letting me examine those documents.

In Cambridge, the staff in the Rare Books Room at the University Library were most helpful, as was Paul Simm at Trinity College, where the Master and Fellows have given me permission to reproduce their portrait of the first Duke of Sussex.

For his help with tracking down references to Lord Archibald Hamilton, I would like to thank Mark Curthoys at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. The ODNB is only one of the Oxford University Press online databases that I have been grateful to access through my Essex Library card.

Charles MacRae located the Harrow School archives, where Rita Boswell found what I needed. At Winchester College, Suzanne Foster was similarly helpful. Heather Purvis at Longford Castle pointed me to a plan of the Radnor mausoleum, which showed where and when Lady Augusta’s sister was laid to rest.

Peter Hunter’s visual memory enabled me to trace the portrait of Lady Augusta’s children; Simon Heffer gave me useful advice at an early stage; Alex Kidson of Liverpool Museums answered all my questions on George Romney and James Bettley lent me his books on Winchester College. I am grateful to the Spedding family at Mirehouse in Cumbria for allowing me to study their Stewart family tree. For his help with the D’Este children, I thank Angus Sladen.

Michael Gray translated some of Augusta’s writings from French into English; Jonathan Foyle discovered the third Earl of Dunmore’s ledger in Lincoln Cathedral and Dido Arthur introduced me to Emma Pound, who gave me information on women’s libraries in the eighteenth century.

In America, Gavin Leckie helped me with the War of Independence. Andrew Watt visited DACOR Bacon House in Washington, where there is a painting of Lady Augusta and her son. DACOR is a private organisation for foreign affairs professionals and I am grateful to them for allowing me to reproduce the portrait.

In Ramsgate, Jaron James took photographs of the 1822 town survey, and the D’Este mausoleum, on which, with the parish church, Margaret Bolton generously shared her knowledge.

In Scotland, Kathy Harley and Richard Ibbetson could not have been more hospitable, going out their way to take me to research appointments. Andrew Widdowson lent me his flat in Edinburgh and Claudia Pleass drove me to Blair Adam on a snowy morning. Catriona Prest had me to stay when I was researching in Kent and while working at the National Archives in Kew I stayed on numerous occasions with Peter and Joanna Wolton. I am grateful to them all.

Brian Mooney has given me unstinting direction in planning and writing and I sincerely thank him.

While any mistakes are mine, a number of people have kindly read the draft: John Martin Robinson, Mary Wolton, Edmund Abel Smith, Diana Heffer, Gail Mooney and Charles Abel Smith.

In the steps of Augusta, my family have accompanied me with grace and enthusiasm to Dunmore, Edinburgh, Teignmouth, Ramsgate, Rome, New York and Virginia. However, I hope that my children, Marina, Nicholas and Edmund, will forgive me for keeping them waiting in uncomfortably high temperatures outside the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library in Williamsburg. My husband, Charles, has been my mainstay.

Contents

Family Trees

Introduction

Part I

1 My Prince – My Lover, and Now, Indeed, My Husband

2 Fine Sprightly, Sweet Girls

3 Welcome to Williamsburg

4 Not Entirely Ill Made, But in Truth Nothing Resembling a Venus

5 Those Scrapes Which a Young Man May Very Easily Fall Into

6 We are the Ton

7 Rather Too Free with the World

8 I Half of You, You, Half of Me

9 He Says He Loves Me

10 I Must Not Will Not Love the Prince

11 We Can Never Be Happy Together

12 The Strong Desire of Doing Right

13 Something Alarming Stops the Effusion of Joy

14 My Darling was Leaving His Unhappy Wife

15 I Hope Never Again to Set My Foot in a Ship

Part II

16 Dear London

17 I Was Again Married

18 This Unpleasant Business

19 Big With the Greatest Mischiefs

20 Anxieties and Miseries

21 The Effects of a Fatal Marriage

22 My Unfortunate Companions of Woe

23 Beggars of Us All

24 I Am to be No Further Troubled on that Subject

25 This Sad Reverse

Part III

26 Dear Ramsgate

27 An ‘Accidental’ Son

28 Keeping Account

29 My Two Treasures

30 A Very Foolish Young Man in Some of His Ideas

31 My Dearest Girl

32 Sad Unhappy Day

33 I Very Ill

34 Sir Augustus D’Este and Mademoiselle D’Este

Epilogue

Bibliography

Notes

Family Trees

Introduction

I discovered Lady Augusta Murray while researching a tropical fruit. I was working as the information officer for the Landmark Trust, a charity that rescues buildings in distress and gives them a future by letting them for holidays. The Trust’s Historian, Charlotte Haslam, and I worked at 21 Dean’s Yard, a neo-Tudor house of five storeys beside Westminster Abbey. It had been the home of the Chapter Clerk and its interior was decorated with Gothic wallpaper from Watts & Co., the ecclesiastical purveyors nearby. Church calm prevailed: Victorian prints hung on the walls and a grandfather clock ticked steadily in the hall. From our dining room on the third floor we had a bird’s eye view of the abbey entrance and enjoyed watching congregations gather for state occasions, but my introduction to the tropical fruit was far away below stairs.

Charlotte’s office was in the former servants’ hall and there she asked me to revise the history album of one of our Scottish buildings: The Pineapple, an eighteenth-century folly near Stirling. Forty-five feet high, it towers above the centre of the walled garden built by Lady Augusta Murray’s father, the 4th Earl of Dunmore. The fruit is a lapidary version of the Jamaica Queen cultivar and from its windows he and his family could admire the garden below.1 It is one of the most famous follies in Britain, yet its architect remains unknown. Charlotte had given me a challenging assignment and I looked forward to searching for architectural drawings and plans; surely I could find a reference to the designer in family correspondence, diaries or bank accounts?

I started work in my sunny office over the porch, where my desk faced Church House, just visible through the London plane trees. Once I watched an unexpected but entertaining fixture: an episcopal hockey match. Occasionally a group of boys from Westminster School, larking down the street, would disrupt the peace but Dean’s Yard was mostly undisturbed.

It was there I encountered Lady Augusta Murray. The most beguiling of Lord Dunmore’s children, she captivated me and the more I researched, the more I wanted to know. Months later I completed The Pineapple history album and although I failed to discover the architect, I could not forget Lord Dunmore’s daughter. I gathered all the information I could on her tragic story, cruelly defined by her marriage to the sixth son of King George III, and I discovered material that has revealed unexpected aspects of Augusta’s character. Some years later I completed my research by reading the wedding registers at the Westminster Archives Centre, one street away from Dean’s Yard where it had all begun.

Part I

1

My Prince – My Lover, and Now, Indeed, My Husband

In the evening of 4 April 1793, preparations were being made for a clandestine ceremony in Rome. The wedding of the son of the King of England to the daughter of the Governor of the Bahamas would not only be concealed, it would also be illegal. That night His Royal Highness Prince Augustus Frederick was married to Lady Augusta Murray without witnesses. The rector of a small parish in Norfolk read the service in the bride’s lodgings: a striking contrast to the wedding of the groom’s parents, which was celebrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Chapel Royal at St James’s Palace on 8 September 1761.

The couple had known each other for only three months but they believed their destiny was entwined. He was Augustus, she was Augusta, and moreover they shared a birthday. They were deeply in love but the consequences of their rash union would be terrible. It was the worst miscalculation of the Prince’s life, but while eventually he found redemption, Augusta’s destiny was changed beyond anything she could imagine. From an eighteenth-century socialite she became a nineteenth-century reject.

Their wedding nearly did not take place. The previous night both the Prince and Augusta had considered suicide. All evening she had waited for her lover but he did not appear. Instead the Reverend William Gunn, the Anglican rector who was to marry them, came to clarify the impediments to their proposed nuptials. When he left she confided in her journal, ‘All my hopes of happiness are fled; where can I fly, where can I go without misery being my constant companion; Mr Gunn will not, cannot marry us.’1

The Prince lay awake in his residence on the Via del Corso nearby. At four in the morning he wrote to her trying to make amends, ‘Such has been my desperate state last night that I was unable to come to you my dearest Augusta, or do anything whatever … My torments and anxieties are so great that with the best principles in the world one might forget oneself.’2 Augusta was not in a mood to look kindly on his excuses. She too had suffered ‘torments and anxieties’ and her patience was exhausted. She tied together every one of his daily letters and returned them, absolving him from his promises.

When his valet brought in the parcel the Prince responded immediately. He told her that if he had received the package the night before ‘it would have encouraged me to have put my criminal purpose [suicide] in execution’. She had also contemplated ending her life and he told her that, ‘If you attempt any thing of the sort I will follow, good God, I am distracted, Angels of Heaven assist me, what an agony I am in … Augusta, revoke your wish of dying.’

Augustus had not eaten for more than two days. Etiolated and delirious, he scribbled another letter to Augusta:

Death is certainly better than this, which, if in 48 hours it [their wedding] has not taken place, must follow; for, by all that is holy, till when I am married I will eat nothing, and if I am not to be married the promise will die with me. I am resolute; nothing in the world shall alter my determination. If Gunn will not marry me I will die … I would rather see none of my family than [be] deprived [of] you … I will sooner drop than give you up … I am half dead. Good God! What will become of me; I shall go mad most undoubtedly … What a dreadful situation I am in; and how can I be otherwise, when she for whom I was taking care of myself will not have me? Life is a burden; but if Augusta will yield, this night I will be hers … If you will allow me, soon after seven I will be at your house, and not care a word for what any one says, but go directly to our room.3

As the day advanced, Prince Augustus became more rational. Despite suffering several asthmatic attacks, he made some plans; whatever happened, they would force Mr Gunn to marry them in Augusta’s rooms at nine o’clock that night. They would disguise their intentions and confuse the poor rector: Augusta would send for him with a pretext and the Prince would be waiting. He told her, ‘I will be with you, and the ceremony must be performed tonight or I shall die … Call me and I will come, nothing shall detain me, I care not what they say to me, what they do, provided I am yours … your friend, your lover and your husband.’ Obediently, Augusta wrote a disingenuous note to the clergyman. She would be happy to see him after he had paid the Prince a call and she would be alone because her mother and sister were going to a party.

When William Gunn arrived at the Prince’s apartment, he was told that His Royal Highness was asleep. Puzzled, the rector set off to keep his appointment with Lady Augusta. Like many British travellers, she was staying in the Piazza di Spagna, the ‘Strangers’ Quarter’, where her mother had taken rooms in the Hotel Sarmiento. Lady Dunmore’s servant, Monticelli, admitted Gunn and, as expected, he found Augusta alone.

A moment later the Prince startled him, coming out of a side room laughing. A prayer book was open at The Solemnization of Matrimony and the rector saw that he had been tricked. Turning to the Prince, he asked, ‘Why do you use me ungenerously? I have always treated you with openness and sincerity?’ Summoning every argument at his disposal, Gunn tried to dissuade the couple from their purpose. He accepted their current despair but explained that if they defied the terms of the Royal Marriages Act by marrying without the King’s consent, their future would be worse. Gunn forecast disgrace and misery for Augusta if they persisted in marrying against a law instigated by the King himself and implored the Prince to consider Augusta’s situation, asking him to respect her ‘in a higher degree’.

William Gunn also knew that Augusta’s seniority would not help her ‘situation’. While both she and Augustus were born on 27 January, the rector knew that she was older than the Prince. Had he known the precise difference in their ages, he would have been even less willing to marry them. At a time when it was frowned upon for a woman to have a younger husband, Augusta was a shocking twelve years older than her fiancé. She was a mature 32 while he was only 20.4

Gunn turned once more to Augustus, who was light-headed with hunger and beyond reason. In tears, Augusta placed the prayer book in the rector’s hands and reminded him of the betrothal promises that she and the Prince had exchanged. Gunn told them to release each other immediately from such bonds, which were nothing more than self-imposed. Augusta then heard somebody on the stairs and rushed from the room. Gunn took advantage of her absence to remind the Prince of ‘your Family, your Rank, your Country, think of your Father, your Mother, and what it is you wish to have done’. He told Augustus that in 1772 the King had passed the Royal Marriages Act to prevent just such a wedding as the one now proposed. The Prince had neither asked, nor received, his father’s permission to marry Augusta and Gunn knew that if he married them, he himself would also be committing a crime.

When Augusta re-entered the room the prayer book was once again thrust into Gunn’s hands and once again he demurred. He suggested marrying them when the Prince came of age the next January but Augustus would not listen. Expecting to be summoned to England imminently, he said that he would not leave Italy without Augusta as his wife and promised recklessly that if they were united, the marriage would remain unconsummated until he was 21, when the ceremony could be repeated.

The rector was defeated. He married the Prince and Lady Augusta with grave misgiving and in his distress left out part of the ceremony. Retaining the wedding certificate, he ensured that both bride and groom were sworn to secrecy. The couple, ecstatic in their relief and joy, tried to express their gratitude but Mr Gunn’s conscience was troubled: he knew he had broken the law. He allowed the newlyweds a kiss before insisting that he and the Prince should leave. Augusta stood aside and against his will, the bridegroom was led away.

She flew to her desk and wrote:

My dearest, and now really adored husband, you are but this moment gone; the sacred words I have heard still vibrating in my ears – still reaching my heart. Oh my prince – my lover, and now, indeed, my husband, how I bless the dear man who has made me yours; what a precious – what a holy ceremony; how solemn the charges – how dear, and yet how aweful!5

Once home, her husband also poured out his feelings: ‘This moment I am come from Augusta. She is mine to all eternity. God has given me her. She is to depend upon me, and no one else.’6 For Augusta the day was ‘ever sacred’ and she wrote, ‘Oh moment that I must record with letters of gold: you are written on the tablets of my heart, you have changed my destiny.’7 As she wrote those words, she could not know how much her marriage would change her destiny: its consequences would prove a tragedy for this warm-hearted and well-meaning young woman.

2

Fine Sprightly, Sweet Girls

Twenty years earlier, the little port of Cowes was bustling. Beneath a steep hill, scattered with cottages, villas and a church, the quay was bounded by Henry VIII’s castle at one end and bristling shipyards crowding the mouth of the River Medina at the other. Business was brisk in the shops, sailors gathered at tavern doors, porters wheeled trunks and boxes and the pilot made preparations. The busy scene presaged a ship’s departure: the Duchess of Gordon was about to leave for New York on 19 November 1773.

Provisions, luggage and cargo were stowed below and finally the Duchess was ready to receive her passengers. A tender ferried a mother and her six children to the ship and when everyone had embarked, the crew raised the sails and heaved up the anchor. The Duchess of Gordon sailed past the Needles, which rose from the waves like rotten molars, and the pilot descended, his job done. Twelve-year-old Augusta was on her way to America, where the family would take up residence with her father, now the Governor of Virginia.

Her older sister, Catherine, and her brother, George, Lord Fincastle, were with her. Her younger siblings Alexander, John and Susan were also aboard but two of Augusta’s brothers were absent. Six months before, William had died aged 9 and 2-year-old Leveson had been left at home in the care of his paternal grandmother.

After forty-four days, the Duchess of Gordon docked on 2 January 1774.1 Augusta’s arrival in New York harbour coincided with one of the most significant periods in American history. The British American colonies resented being taxed without parliamentary representation and their relationship with Britain was deteriorating. A couple of weeks before, ‘The Incident’, known today as the Boston Tea Party, had taken place in Massachusetts.

On the night of 16 December 1773 a small band of colonists, disguised as Native Americans, boarded three ships in Boston harbour. Their mission was to ransack the cargoes of East India Company tea, a commodity detrimental to the American market, but forced onto it by the British Tea Act. The colonists tore open every chest and poured the contents overboard. The British Government reacted by closing the harbour until the requisite duty had been paid on the lost tea. This measure ensured that the commercial life of Boston, a town reliant on shipping, was brought to a standstill; with their prosperity threatened, the citizens and merchants began to plot.

Meanwhile, Lady Dunmore and her children recovered from their passage in New York and waited for the weather to improve before continuing their journey south. A New Yorker, known for criticising newcomers, was charmed. ‘Lady Dunmore is here,’ he wrote:

[she is] a very elegant woman … Her daughters are fine sprightly, sweet girls. Goodness of heart flushes from them in every look. How is it possible, said that honest soul, our Governor, to me, how is it possible my Lord Dunmore could so long deprive himself of those pleasures he must enjoy in such a family? When you see them you will feel the full force of this observation.2

This was unmerited criticism; Lord Dunmore had missed his wife and children and the combination of her husband’s entreaties and her slender means had encouraged Charlotte Dunmore to pack up and move to the New World.

The Earl of Dunmore had taken the governorship because he needed money. When he married Lady Charlotte Stewart, a younger daughter of the 6th Earl of Galloway, in 1759 he had been a rich man, having inherited a spectacular legacy from his uncle. Unaccustomed as he was to such wealth, Lord Dunmore had spent it too freely. He built the walled garden at Dunmore and topped it with the extravagant pineapple, and he bought the Glenfinart estate on the western shore of Loch Long. The earl was also profligate in his dress and one lavish waistcoat, copiously embellished with gold lace, caused a stir amongst his friends in Edinburgh.3

When staying in the Scottish capital, the family occupied the suite of rooms in the royal palace at Holyrood that Queen Anne had granted her old friend and Master of the Horse, the 1st Earl of Dunmore. Landed families often wintered in Edinburgh, so when Augusta was born on 27 January 1761, the event probably took place at Holyrood. Three months after her birth, Augusta’s father became a Representative Peer for Scotland, one of the sixteen Scottish peers elected to sit in the House of Lords under the terms of the Act of Union.

The appointment required him to live near Westminster when parliament was sitting and he moved his family to a large house in Lower Berkeley Street (now called Fitzhardinge Street) between Manchester and Portman Squares. The earl enjoyed his new status and he and the countess moved in London circles with friends such as the future prime minister, Lord Shelburne, and Lord Weymouth, the heir to Longleat. In keeping with his rank, Dunmore commissioned Sir Joshua Reynolds to paint his portrait in full length, a pose reserved for royalty and the nobility. Reynolds was one of London’s most costly artists and the painting remained in his studio, unpaid for; today it belongs to the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh and dominates any room in which it is hung. By the time that Augusta’s younger sister, Susan, was born in 1767, Lord Dunmore had run up debts of £7,000 and had to ask his cousin, the Duke of Atholl, for a loan of £2,000. He explained that he could repay it only if he acquired a position yielding a substantial income.

The earl’s prospects brightened when his sister-in-law, Lady Susanna Stewart, married Granville Leveson-Gower, a politician favoured by the King. With the patronage of his new relation, Dunmore was selected as Governor-in-Chief of the province of New York, whereby he was granted the much-needed salary of £2,000, which came with the possibility of American land grants. Like many other Scots who took colonial office, Dunmore’s estates were not enough to support him and the appointment was a pecuniary relief. He was dismayed at leaving his wife, described by Lady Sarah Lennox as ‘charming and Scotch’, and his delightful children, which a friend had called ‘the finest he ever saw’.4

In 1771, after a year in New York, Dunmore was assigned as Royal Governor of Virginia. For most of the eighteenth century, governors of Virginia stayed in London and their lieutenants performed the role in Williamsburg. As the King’s representative in the colony, the lieutenant governor was in charge of matters civil, military, judicial, fiscal and religious. In 1768 however, against the background of uneasy relations between America and Britain, and mindful of the colony’s economic importance, the government attempted to woo the people of Virginia by appointing a full royal governor, Lord Botetourt, who resided in Williamsburg. When Botetourt died unexpectedly in 1770, the post was offered to the Earl of Dunmore.

He had not been pleased, protesting, ‘Damn Virginia. Did I ever seek it? Why is it forced on me? I asked for New York – New York I took, and they robbed me of it without my consent.’ He was reluctant to take up the post because he thought that Virginia was remote and unhealthy. Lord Botetourt had died of a fever after two years in office and Dunmore was unhappy about exposing his wife and children to the South, which was humid and insalubrious in summer.

The thought of leaving New York was anathema, but Virginia, a larger and more prosperous colony, offered Dunmore a better salary and therefore he accepted the post. Moreover, of all the American colonies, Virginia was in a league of its own. Protestant pilgrims, fleeing Episcopalian Anglicanism, had settled in New England, whereas aristocratic landowners, who had crossed the Atlantic to make money and to escape the Puritan ascendancy in England after the execution of Charles I, populated Virginia. Gentlemen, inhabiting elegant tideway houses on plantations up and down the James and York rivers, grew tobacco, a lucrative business dependent initially on indented and later on slave labour. When Dunmore reached Williamsburg in 1772, the town’s population comprised 52 per cent black and 48 per cent white people, the former working on plantations and in domestic service.

As he had feared, soon after his arrival the earl became ill. Home leave to recover his health was conditional on resigning his post, something he could not afford to do. Consequently, in May 1773 Dunmore decided to stay and despatched his secretary to escort the gubernatorial family to Williamsburg.

3

Welcome to Williamsburg

After a month in New York, the countess, her children and ten servants set out for Virginia. They went by carriage to Philadelphia, the largest city in the British American colonies, and on to Annapolis, capital of Maryland. On the quay they boarded the governor’s schooner, tactfully named Lady Gower after the wife of Lord Dunmore’s patron, who had played such an important part in helping procure his appointment. Sailing down the Chesapeake Bay past the mouths of the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, after three days they entered the York River and made their way towards the south bank. On 26 February 1774 Lady Gower docked at Yorktown, one of Virginia’s busiest deep-water ports and soon to become famous as the site of Lord Cornwallis’s surrender at the end of the War of American Independence.

The arrival of the governor’s family was almost as momentous as a royal visit. Awed and fascinated, the tobacco farmers and slave owners, many of them recent immigrants from England and Scotland, crowded the riverbank. Town officials had arranged a cannon salute to greet Lady Dunmore but despite their careful plans a distressing accident with gunpowder marred what should have been a dignified and joyful ceremony. The Virginia Gazette described the horror:

Mr. Thomas Archer, and Mr. Benjamin Minnis, being extremely active in managing the cannon, but by ramming the rod too violently against the iron within, it occasioned a kind of friction … which communicated to the powder, and the above gentlemen being very near the gun when it went off … received considerable damage; the arms, face, and eyes, of Mr. Archer, being bruised in a most dreadful manner. Mr Minnis was much hurt in the thigh, and otherwise terribly wounded. Captain Lilly was also bruised about the eye, though slightly. Two Negroes that assisted were dreadfully mangled, one of them having lost three fingers off his right hand; the other is so much burnt in the face, and his eyes are so much hurt, that is thought he will never recover their use. Fortunately, none of their lives are despaired of.1

The incident did not bode well.

Departing in a state of shock, the governor’s family crossed Yorktown Creek. The last 12 miles of their journey to Williamsburg took them over marshes and through woods of oak, maple and pine.

The capital of Virginia rejoiced at the prospect of a royal governor, his wife (herself the daughter of an earl) and their six children living in the Governor’s Palace. Earlier in the month, John Byrd, a student at William and Mary College, told his father that the town was making preparations ‘for the reception of Lady Dunmore, fireworks, with great illuminations, for which I understand there is a large subscription made’.2 Now the waiting was over.

At seven o’clock in the evening crowds of well-wishers, calling out ‘Welcome to Williamsburg’, met the governor’s carriage, which was emblazoned with the arms of the colony of Virginia on one side and those of the Earl of Dunmore on the other. It entered the town accompanied by children and youths. On Duke of Gloucester Street, the town’s principal thoroughfare, windows were illuminated and that evening, throughout the town, gentlemen raised their glasses to ‘the Governor of Virginia and his Lady just arrived’ and ‘Their Majesties’, and more tellingly, they raised their glasses to ‘Success to American Trade and Commerce’.

The carriages containing Lady Dunmore, her children and attendants turned into Palace Green, an open space bordered by catalpa trees, and drew up by the governor’s residence at the end. Augusta stepped down after her mother and Catherine; Susan followed her and the boys descended from another carriage. Lord Dunmore had not seen his family for over four years and the Virginia Gazette celebrated their reunion in lines dedicated to his wife:

Hail, noble Charlotte! Welcome to the plain,

Where your lov’d Lord presides o’er the domain:

But who can speak the rapture that he proves,

To see at once six pledges of your loves?

Your lovely offspring crowd to his embrace,

While he with joy their growing beauties trace;

And while the father in his bosom glows,

The tears of pleasure from each cherub flows;

All eager pressing round about his knees,

In sweet contest, their father most to please.

O charming group! So blooming, and so fair,

In virtue rear’d by thy maternal care.3

Augusta, the second of the ‘six pledges’ of her parents’ love, was now 13 years old and overjoyed to see her father.

Her new home, the scene of so much imagined and real delight, was one of the handsomest houses in the colony. After the Dunmores’ departure the palace became a hospital for soldiers wounded at the battle of Yorktown and in December 1781 it caught fire. However, in 1934 it was opened to the public having been rebuilt from its foundations and restored to its original appearance with Rockefeller funding. Today, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation presents it as the eighteenth-century residence of the last royal governors and it appears once again as the home that Augusta would recognise.

The palace is ‘of special importance to America, as the first great classical mansion of Virginia’.4 It had been built in the Queen Anne style: a symmetrical red brick house of two storeys, with dormer windows in the steeply pitched slate roof. A glazed lantern, topped by a cupola and weather vane, surmounted the roof balcony and tall chimneys on either side enhanced its silhouette. The entrance hall doubled as an armoury and the walls were decorated with shields, pistols and swords, while a display of muskets with fixed bayonets radiated from the ceiling. The royal coat of arms reminded the visitor of the governor’s vice-regal status.

Augusta’s bedroom was on the first floor, across the landing from her parents’ suite, and her brothers slept on the floor above. When she looked round the twenty-five rooms, although much was new and strange, Augusta recognised some items from home: hexagonal plates with the family coat of arms and portraits by Sir Peter Lely.5 She was pleased to learn that dancing was a favourite pastime in Virginia and admired the ballroom at the back of the house. Coronation portraits of King George III and Queen Charlotte, painted by Allan Ramsay, her father’s acquaintance in Edinburgh, hung on its walls. Charlotte’s small figure was draped in ermine and blue velvet and her left hand lay on her crown, which was placed on a matching blue velvet cushion. George III, staring into the distance, was dressed in a gorgeous golden suit, flowing ermine and the collar of the Order of the Garter; like his wife, he stood on a thick turkey carpet. The painted presence of Their Majesties was another powerful reminder of the royal authority vested in her father.

From the supper room beyond the ballroom, double doors led into the garden, which Lord Botetourt described as ‘well planted and watered by beautiful Rills, and the whole in every respect just as I could wish’.6 At the side of the flower gardens, terraces ran down to a canal and there was a maze and an icehouse. Beyond the garden 150 cattle grazed in the Governor’s Park, where Lord Dunmore took his morning walk; in the summer he cooled down in the hexagonal bathhouse.

Augusta’s home was the centre of administration for the governor of Virginia. Visitors to the house, planters, soldiers, sea captains, officials and messengers passed through a sequence of spaces, culminating in an audience with the governor. They came down Palace Green, through the wrought-iron gates into the courtyard and up the steps to the front door. From the impressive hall they were shown into the adjacent parlour, where they waited before being escorted upstairs and admitted to her father’s private office, the ‘great Room’ lined with gilded leather.

While her husband was administering the colony of Virginia, Lady Dunmore did not neglect her daughters’ education. A girl from Augusta’s background was expected to excel in the gentler arts and she learnt needlework, drawing and dancing. She was fluent in French and although she told Prince Augustus later that she regretted her lack of musical accomplishment, there was plenty of opportunity for her to practise in Williamsburg. There was a harpsichord and piano as well as three organs and other musical instruments in the palace. Her father encouraged her to read and she sought sanctuary in his ‘valuable Library consisting of upwards of 1,300 volumes’ opposite her bedroom.7

Her brothers were enrolled at the College of William and Mary, Virginia’s venerable seat of learning. Indeed its existence had been a factor in Lord Dunmore’s decision to bring his family to America, and in the Wren Building (a colonial version of London’s Chelsea Hospital) the boys learnt mathematics, geography, the classics and ‘penmanship’.

William and Mary College was located at the west end of Duke of Gloucester Street. At the east end was the Capitol, which housed Virginia’s highest court, and the legislative assemblies. Copying the Westminster formula, the Capitol was divided into two parts: the King’s side comprised the General Court and the Council Chamber, or meeting place of the upper house. The debating chamber of the lower house, or House of Burgesses, was on the other side and one of its most distinguished members was Colonel George Washington, the senior burgess for Fairfax County.

As a young girl, Lady Augusta Murray met the man who would become the first President of the United States. Colonel Washington and Lord Dunmore were united in their zeal for investing in land and allocation of land title was in the governor’s gift. The year before Augusta arrived, a land-surveying expedition planned by her father and Washington was cancelled when Washington’s stepdaughter died of epilepsy. It is unclear whether their friendliness was based on their mutual interest in acquiring land or whether it was political expediency on Washington’s part, probably both, but it appears that, until their relationship was affected by revolutionary events, there was a degree of warmth between the two men.

In July 1772 Washington had hoped to receive the governor at Mount Vernon, his home in Fairfax County, and told him that he had looked in vain ‘every hour for eight or ten days for your Lordship’s Yacht’ sailing up the River Potomac.8 In December 1773 he sent the governor a barrel of hawthorn berries and like Dunmore, he shared a love of pineapples. When he was in Barbados in 1751, Washington confessed that of all the fruits he found there ‘none pleases my taste as do’s the Pine’.9

When in Williamsburg for meetings of the General Assembly, the colonel was often a guest at Lord Dunmore’s table. On 16 May 1774 he dined at the palace for the first time since the arrival of the governor’s family and we can imagine Augusta’s father proudly introducing his wife and six children to George and Martha Washington. However, when the colonel dined and spent the evening at the palace a few days later, political events in Virginia had caught up with the ‘incident’ in Boston harbour.

On the morning of 16 May, Washington had been present in the House of Burgesses when it resolved to set aside 1 June as a time for fasting and prayer for a successful outcome to the altercation between Boston and London. Later at the palace he did not allow civil disobedience in a distant port to spoil a good dinner. The next morning, according to his diary, Washington ‘Rid out with the Govr. to his Farm and Breakfasted with him there’.10

It was only the next day that the significance of the ‘Boston Tea Party’ became obvious.

On 17 May Lord Dunmore learnt of the Williamsburg burgesses’ proposal for the day of prayer and fasting. Furious, he commanded them to assemble immediately in the Council Chamber where, gripping their resolution, he thundered, ‘I have in my hand a paper published by order of your House, conceived in such terms as reflect highly upon His Majesty and the Parliament of Great Britain; which makes it necessary for me to dissolve you; and you are dissolved accordingly.’11 Lord Dunmore failed to intimidate the burgesses. They merely reassembled at the Raleigh Tavern and formed the Virginia Association, agreeing that deputies from the colonies of British America should ‘meet in general congress, at such place annually as shall be thought most convenient; there to deliberate on those general measures which the united interests of America may from time to time require’.12 The fissure in Virginia’s relationship with Britain was widening.

The timing of Dunmore’s dissolution was unfortunate because the House of Burgesses had arranged a subscription ball to welcome Lady Dunmore the next night. Everyone was determined not to lose face and the burgesses continued with their plans for the dance. As Washington’s biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman, has written, it was:

an extraordinary, a paradoxical, an amusing and, withal, an enjoyable affair: the hosts were to be put to the bother and expense of a canvas and a new election for no other reason than they had decided to have a fast day; all the same, as gentlemen, and at £1 per capita, they bowed low to the wife of the man who had dissolved their House.13

In the Capitol the burgesses received Lady Dunmore graciously as the highest-ranking lady in North America and she was welcomed and fêted by the best of Virginia society: the Byrds, the Lees and the Jeffersons. The countess appreciated their courtesies for she loved a party and was an accomplished dancer.

There was one burgess however, who had been unable to attend the ball. While George Washington was dancing at the Capitol, hundreds of miles away on the banks of the River Ohio an uneasy land surveyor, Colonel William Preston, was writing him a letter. The British Government’s undertaking, under the terms of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to protect Native American land rights west of the Appalachian Mountains was another reason for American colonists’ disquiet with the mother country. Virginian tobacco planters were in constant need of ‘plenty of cheap land to replace the acres wasted by soil-exhaustion and soil-erosion, the marks of inefficient agriculture’ and Native American tribes had resented the settlers’ incursions on their lands south of the Ohio for many years.14 Tales of torture, scalps and abduction did nothing to calm the nerves of the white settlers and their surveyors. In his letter, Preston told Washington of the recent disappearance of three of his party and his fear of the Native Americans, who were hindering his business. Contrary to the Proclamation, Lord Dunmore supported the Virginian settlers. He was also concerned by the dispute further up river between Virginia and Pennsylvania over the area around Fort Pitt (present day Pittsburgh). On 10 June he instructed his lieutenants in the frontier counties to start raising militia to act against the towns of the Shawnee tribe across the Ohio.

Charlotte Dunmore was now expecting another child. As her pregnancy progressed, her husband was preparing to lead a detachment of 1,400 men from Williamsburg across the Appalachians to participate in the campaign known today as ‘Dunmore’s War’. The governor departed for the Ohio River with the approbation of the Virginians, but it was an anxious time for his wife and children left at home. He arrived at Fort Fincastle (present day Wheeling) to the south-west of Fort Pitt on 30 September 1774. A few days later, the Shawnee were routed and the governor began to negotiate with the defeated tribe at Camp Charlotte, a new fort, which he named after his wife. By a treaty of friendship, Cornstalk, the Shawnee Chief, renounced his tribe’s hunting rights south of the Ohio, leaving the way free for future Virginian settlements.15 Returning home a hero on 4 December, John Dunmore discovered that Charlotte had given birth the day before.

The Virginia Gazette reported that, ‘Last Saturday morning the Rt. Hon. the Countess of Dunmore was safely delivered of a daughter, at the Palace. Her Ladyship continues in a very favourable situation, and the young Virginian is in perfect health.’ For Augusta the joy was twofold. Her father had returned safely from a military campaign and her mother had survived a process no less perilous: that of giving birth.

In 1775 Williamsburg celebrated Queen Charlotte’s birthday on 19 January and began with the christening of the governor’s daughter at Bruton parish church on the corner of Palace Street. The baby received the name ‘Virginia’, as requested by the General Assembly and happily agreed by the governor; indeed the victorious expedition to the Ohio had elevated Lord Dunmore’s standing to such an extent that no other name would have been acceptable. Fifty years later, Lady Dunmore told John Quincy Adams, America’s Minister Plenipotentiary to Great Britain, that George Washington held Virginia at the font.16

The festivities continued that night with a birthday ball at the palace. It was a splendid occasion but not for the faint-hearted. The kitchens were instructed to cater generously to sustain the dancers’ stamina. Five meats were served, glass épergnes were filled with candied fruits and sugared nuts, and a choice of desserts (pastries, syllabubs and jellies) were displayed on crystal stands down the middle of two tables in the Supper Room. At midnight the musicians struck up again after supper and the dancing continued. Lord Dunmore requested Scottish reels, and the cotillions, rigadoons and gavottes did not cease until nine o’clock the next morning, when the musicians packed up their instruments and the last guests departed. It had been a spectacular success and although nobody knew it at the time, the celebration for Queen Charlotte’s birthday would be the last ball hosted by a royal governor at the palace in Williamsburg.

Later in 1775 the governor and his family sailed down the James River to Norfolk, where Augusta had another opportunity to dance. Norfolk, an important trading city with warehouses lining the quay, returned one burgess to the General Assembly of Virginia. Years later an ‘Old Burgess’ recalled the sensation that the governor’s wife and his daughters caused on the dance floor:

the fiddles struck up; and there went my Lady Dunmore in the minuet, sailing about the room in her great, fine, hoop-petticoat, (her new fashioned air balloon as I called it) and Col. Moseley after her, wig and all. Indeed he did his best to overtake her I believe; but the little puss was too cunning for him this time, and kept turning and doubling upon him so often, that she flung him out several times … Bless her heart, how cleverly she managed her hoop – now this way, now that – everybody was delighted. Indeed we all agreed that she was a lady sure enough, and that we had never seen dancing before.

It was high praise from a resident of Virginia, a colony that prided itself on its prowess on the dance floor.

After Lady Dunmore’s display, the mayor danced a minuet with Lady Catherine, then the ‘Old Burgess’ recalled Captain Montagu taking out ‘Lady Susan’ and ‘the little jade made a mighty pretty cheese with her hoop’.17 Susan was then aged only 6, so the ‘little jade’ was probably Augusta. George Montagu was a 24-year-old naval captain with a distingué presence and an elegant Roman nose.

Soon after Augusta’s 14th birthday in 1775, an event in Richmond provoked her father to authorise a manoeuvre that resulted in his family fleeing America. Discontent over Westminster’s measures for taxing the colonies continued to fester and at the Second Revolutionary Virginia Convention in March, Patrick Henry, an orator of exceptional power known as the ‘firebrand’, proposed assembling and training a revolutionary militia. He concluded his call to arms with, ‘Almighty God – I know not what course others may take; but as for me – give me liberty, or give me death!’ With his young family living at the palace, Lord Dunmore felt increasingly vulnerable, both politically and personally, and the prospect of rebellion horrified him. His next step however, inflamed the colony and hastened more than any other its progress towards revolution.

The ‘Powder Incident’ took place between three and four o’clock in the morning of 21 April 1775 at the magazine on Duke of Gloucester Street. Surrounded by a protective wall, it was an octagonal brick building designed to hold a substantial arsenal with everything necessary to wage a minor battle: guns, bayonets, pistols and gunpowder, all imported from England for the protection of the colony of Virginia.

Lord Dunmore instructed Captain Henry Collins, commander of HMS Magdalen, to seize the gunpowder and remove it to his armed schooner moored in the James River. Silently, a detachment of marines crept up to the magazine, loaded the barrels of gunpowder into the governor’s wagon and, undetected, drove it through the quiet streets. Nobody raised the alarm but with daylight came the discovery that the people of Virginia could not defend themselves. Alarmed and exasperated, the citizens cried ‘To the Palace’.

The family heard angry noises outside. A party of gentlemen, members of Williamsburg’s municipal council, then arrived requesting clarification for the clearing of the magazine. While the noise from the crowd increased, Augusta could see the back of her father addressing the throng from the first floor balcony of his office. He told them that if the powder were needed it would be delivered in half an hour and that it was now in a secure place. His explanation did not satisfy the crowd and Augusta heard more shouts and threats before the people dispersed.

Lord Dunmore was now gravely concerned for the safety of his wife, children and 4-month-old baby, Virginia. As he wrote to Lord Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for America, he was obliged to shut himself in ‘and make a Garrison of my House, expecting every Moment to be attacked’.18 He instructed the household to arm itself and weaponry, previously displayed in the entrance hall, was made available. The governor’s home was now a fortress. Augusta’s visits, excursions and outings to the shops ceased and armed servants accompanied her in the garden. Thus imprisoned, the helpless family and their servants became more and more afraid.

The ‘Powder Incident’ had given the counties of Virginia an excuse to raise their militias. The people began to arm themselves and volunteers gathered in the capital. Meanwhile, on 3 May the Hanover County militia, under the control of Patrick Henry, never one to exercise restraint, advanced to within a few miles of Williamsburg, and in the governor’s words ‘encamped with all the Appearances of actual War’ trying to cut off any help that might come to His Excellency from HMS Fowey lying off Yorktown.19 Henry demanded financial restitution from the governor for the powder. Dunmore arranged for £330, the estimated value of the powder, to be sent to Henry to avoid an attack on Williamsburg and more precisely the palace. Tension mounted when the governor arranged for cannon to be planted in front of the palace and, despite Henry’s best efforts, a group of marines marched from Yorktown to guard the governor’s residence.

Lord Dunmore began to make secret preparations for the evacuation of his family and explained to the children that they must go with their mother to Yorktown, where they would be escorted to the man-of-war waiting at anchor. It was a terrible leave-taking. Augusta’s father was left alone in his fortified home at the mercy of the rebels, while his frightened family drove to Yorktown. Augusta recalled her first journey from Yorktown to Williamsburg, full of excitement and anticipation. Now she was departing by stealth in an unmarked carriage. Arriving at Yorktown that night, they were rowed out to HMS Fowey. Safely on board, Augusta discovered that the ship’s captain was her dancing partner in Norfolk, George Montagu.

Meanwhile, Lord Dunmore had received orders from London to submit a proposition called ‘The Olive Branch’ to the General Assembly and he summoned a meeting at the Capitol on 12 May. Williamsburg became tranquil and the marines, nicknamed ‘Montagu’s boiled crabs’, left the palace. Lady Dunmore and the children were able to return, according to the Virginia Gazette ‘to the great joy of the inhabitants … who have the most unfeigned regard for Her Ladyship, and wish her long to live amongst us’. On 13 May the newspaper, in a blacker mood, discussed ‘the danger arising to the colony by the loss of the public powder, and of the conduct of the Governor, which threatens altogether calamities of the greatest magnitude, and most fatal consequences to this colony’. The governor’s correspondence was intercepted and often published, and a number of loyalists began to leave the colony. After nearly a month, Lord Dunmore realised that his position was untenable and he could not guarantee the welfare of his family in Williamsburg.

Before dawn on 8 June 1775 Augusta was awoken and told to dress. The family assembled downstairs with the baby and her nurse and the small group moved silently through the peaceful house to the ballroom and left by the back door. In the garden they avoided the gravel paths and hurried down the grass verges to the carriages waiting at the back to take them to safety. By two o’clock in the morning the last royal governor of Virginia and his family had left the palace forever.

The Virginia Gazette of 10 June announced their departure and printed the following message left by the governor for the Assembly:

Being now fully persuaded that my person, and those of my family likewise, are in constant danger of falling sacrifices to the blind and immeasurable fury which has so unaccountably seized upon the minds and understanding of great numbers of the people, and apprehending that at length some among them may work themselves up to that pitch of daringness and atrociousness as to fall upon me in the defenceless state in which they know I am in the city of Williamsburg, and perpetrate acts that would plunge this country into the most horrid calamities, and render the breach with the mother country irreparable; I have thought it prudent for myself, and serviceable for the country, that I remove to a place of safety, conformable to which I have fixed my residence, for the present, on board His Majesty’s ship, the Fowey, lying at York.

Finally, he expressed the vain hope that he would be visited on board by some of their members.

Augusta’s stay in America, which had started with good will and a hearty welcome from the people of Williamsburg, ended with a midnight flight and her father’s ignominy. Virginia had venerated the goose and her goslings, but by the summer of 1775 it could not endure the gander; the only prudent option was for Lady Dunmore and her children to return to Britain. On 29 June they boarded the Magdalen and Lord Dunmore, aboard the Fowey, accompanied his wife and children down river as far as Chesapeake Bay. Before sailing through the Virginia Capes and into the Atlantic, Lady Dunmore and the children bade the governor a final farewell from the Magdalen’s deck and, with a dip of the flag, Captain Montagu turned back towards Yorktown. As America receded, Augusta’s spirits sank.

Without the support of his family, the governor was left to fulfil his duties in a rebellious and hostile land. He concentrated on bringing Virginia to heel. In one of ‘his diabolical schemes’, Lord Dunmore managed to unite both patriots and loyalists against him by issuing an inflammatory proclamation. On 7 November 1775 he offered freedom to any rebel-owned slave willing to fight for the King. In so doing, he incensed his former dinner companion, George Washington. The day after Christmas, Washington wrote to Richard Henry Lee, one of Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress, telling him that if:

that Man is not crushed before Spring, he will become the most formidable Enemy America has – his strength will Increase as a Snow ball by Rolling; and faster, if some expedient cannot be hit upon to convince the Slaves and Servants of the impotency of his designs … I do not think that forcing his Lordship on Ship board is sufficient; nothing less than depriving him of life or liberty will secure peace to Virginia.20

Lord Dunmore’s attempts to reclaim Virginia with the assistance of his so-called ‘Ethiopian Regiment’ were unsuccessful. Threatening further incursions from HMS Fowey, the governor continued to menace Virginia until he was defeated not only by the rebel army, but also by starvation and sickness in his own ranks. Unlamented by most Virginians, he eventually sailed to New York where he took part in the battle of Long Island. In November 1776 Lord Dunmore, one of the most hated British officials, left America. With hopes of regaining Virginia temporarily dashed, he returned to England, with his life and liberty intact, just before Augusta turned 16.

From 1774 to the middle of 1775 she had lived in Williamsburg as the daughter of Virginia’s last royal governor. In an era when girls of her age rarely went abroad, Augusta’s unique experience gave her a worldliness and confidence that set her apart from her peers at home. Later she could recall that she had met some of the chief protagonists in America’s break with the mother country: a cruel and very bloody civil war, which caused immense upheaval and lasted eight years. She could look back to some of the early events in a campaign that changed Britain’s relationship with its former colony forever, for she had watched the beginning of the end of the British Empire in America.

4

Not Entirely Ill Made, But in Truth Nothing Resembling a Venus

When the Countess of Dunmore returned from America in the autumn of 1775, she took a house in Twickenham. The fashionable and elegant Thameside village had been popular with the Scottish since Charles I had granted Ham House to William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart.1 It was a two-hour carriage ride from London and Lady Dunmore could let their house in Lower Berkeley Street. Augusta’s new home, Colne Lodge, was a villa surrounded by pleasure grounds on the bank of the River Colne, which here emptied into the Thames.

We know little about Augusta’s life in the six years after she left Virginia. In September 1781, when British troops were defending Yorktown during the final campaign of the American War of Independence, William Beckford informs us that Augusta attended his coming of age celebrations. She had family connections with Beckford, who was half Scottish. His mother was a Hamilton and a close friend of Augusta’s aunt, Euphemia.

The Beckford festivities were held in Wiltshire. Augusta travelled there with her cousin, Lady Margaret Gordon, whose engagement to William, Mrs Beckford and Euphemia had been plotting. Beckford’s late father had been a Jamaican sugar baron of stupendous wealth and the opulence of his son’s gala befitted the indulgence of William’s youth. He had studied architecture with the King’s tutor, William Chambers, and piano with Mozart.

In a letter to his cousin Beckford described the preparations for the revels as ‘perpetual bustle’ with his home exhibiting ‘an appearance little better than Bartholomew Fair’.2 Fonthill Splendens, his father’s Palladian house, stood in a park with a lake, woods and groves, temples, a grotto and a pagoda. Such was the backdrop to the fête-champêtre