8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

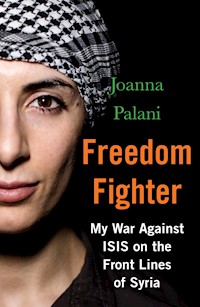

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The gripping story of one woman's war against ISIS on the frontlines of Syria. Joanna Palani made headlines across the world when her role fighting ISIS in the Syrian conflict was revealed. She is one of a handful of western women who joined the international recruits to the Kurdish forces in the region and this is the first time her extraordinary story has been told. Inspired by the Arab Spring, Joanna left behind her student life in Copenhagen and travelled to the Middle East in order to join the YPJ - the all-female brigade of the Kurdish militia in Syria. After undergoing considerable military training, including as a saboteur and sniper, Joanna served as a YPJ fighter over several years and took part in the brutal siege of Kobani. Despite her heroism, she was taken in to custody on her return to Denmark for breaking laws designed to stop its citizens from joining ISIS, making her the first person to be jailed for joining the international coalition. In this raw and unflinching memoir, Joanna not only provides an eye-witness account of this devastating war but also reveals the personal cost of the battles she has fought on and off the frontlines.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

I dedicate this book to the many girls and women, especially in Kurdistan, who are still fighting for the sexual revolution in the Middle East.

Contents

Prologue: Between Two Buildings

1 Daughter of the War in the Desert

2 Growing Up Kurdish

3 Rights Before Rules

4 Journey into Syria

5 Aleppo Begins to Crumble

6 The Real Revolutionaries of Rojava

7 The Friendly Agents of the PET

8 The Martyrs of Kobani

9 Stuck in the Mountains

10 Peshmerga Poster Girl

11 Pregnant Little Girls

12 Over Borders, Under Scrutiny

13 Evolution of Tactics

14 Selfies on the Manbij Frontline

15 Munitions and Mind-Games

16 Aftershocks

Acknowledgements

PROLOGUE

Between Two Buildings

September 2014

We’d been without food inside our house in Kobani in northern Syria for more than three days when I decided it was time to go and try to find some. I couldn’t call where we were staying a ‘safe house’ because there wasn’t one building in the city that was safe from ISIS at the time. Selected on the basis that it was one of the oldest houses we could find, it had thicker walls than the newer, half-finished buildings that make up much of the city. Bullets pass easily through cheap concrete and blast-stone buildings, but they struggle more with older, handmade walls.

I woke up cold after a night sleeping upstairs huddled in between two YPJ girls I had befriended, Amara and Bercem. It was our third night spent camped together as a trio in the room our unit used as a bedroom, but I had been tossing around and I knew the others were annoyed. Shortly before midnight Bercem put her leg over mine, and the warm weight of her had forced me to be still long enough to get to sleep. I woke up with my arm curled around Amara, but the breeze from the window closest to us, reaching my back, told me that Bercem was no longer behind me. I slept in my uniform, as we all did, and this morning marked eleven days without a shower. I slowly made my way downstairs to our yard, where some of the younger girls were already up, piously cleaning weapons, and through to our kitchen to make myself some tea, as my stomach knotted with hunger.

The Women’s Protection Units, the YPJ, fight together with the men; and we all make up the YPG. We believe that women and men are equal, so we fight together for the freedom of the Kurdish people and the destruction of ISIS. There were sixty-four of us fighters spread across four houses in the south of the city of Kobani at the time, and fifteen stationed in our house. Our four locations were near the central market; and we were close enough to each other to send commands and move swiftly, when need be. We shared one fresh-water tap in the yard and our house was divided into three rooms: one for cooking, one for sleeping and resting and one room to go to the toilet. ‘Toilet is out of bounds until further notice,’ my commander explained over breakfast. ‘We don’t want Daesh to be alerted to our position by the stench,’ Ameena added, and a few people laughed as our commander tried to raise a smile. Breakfast was sweet, hot blackberry tea and sugar. There was no bread left, and the logistic supply trucks – we just call them ‘logistics’ – had been delayed and blocked from getting in again. Opposite our house was an abandoned kebab grill, and that particular morning the faded pictures displayed in the windows felt like torture.

There was no power, so at night we sat together in the candlelight, drinking tea and talking politics, but for the last few nights the only thing on our minds was food. Supplies had become increasingly scarce as the summer passed, and by the time our unit – or tabur, as we say in Kurdish – arrived in Kobani, they had dwindled to virtually nothing. With Turkey to our north and ISIS everywhere else, we were effectively blockaded, or something very like it, but no one wanted to show they were scared, so we continued to behave as normal. We didn’t expect to be attacked as quickly as we were in Kobani, as we thought ISIS would focus on cities near the oil fields such as Kirkuk, in the very heart of Kurdistan. So the siege was unexpected – if there really is such a thing in war, because a soldier should always be prepared for the unknown. Looking back and seeing the mistakes we made in Kobani is like having a ticket for a train that’s already left the station. It’s a painful and fairly useless exercise. We couldn’t do anything more than stand our ground and fight with what we had.

We had been waiting for weapon supplies to arrive so we could push forward, but they had yet to materialize, so I spent long evenings on guard patrol on the roof of our house, watching through the cracked scope of my AK rifle as ISIS erected their black flags closer and closer to our position. They had been moving fighters into the region all summer long: they wanted to be seen internationally as being on Europe’s doorstep. We shared our weapons among our unit, mainly cheap, black-market semi-automatic assault rifles, and munitions were at a premium as we were short of materials. Every morning and evening our AKs would be lined up and cleaned, as if polishing them would suddenly transform them into proper equalizers. There was sometimes some shuffling to get one of the better AKs, but we have a culture of sharing, so more often there would be a long conversation over who should have the less reliable weapon: normally the more experienced fighter. The gun I was eventually assigned had a broken bayonet holder, so I had to fashion one of my scarves around it to hold my knife securely in place. We were depending on a fresh logistics shipment, as there were far more ISIS soldiers than us and they had far better weapons. When US planes did eventually drop weapons from the Iraqi Peshmerga forces to us, many landed in areas recently taken from us by ISIS, who were everywhere.

My fellow fighters were girls and boys often far younger than me, and I was proud to fight with them. We were defeating the greatest evil the world had ever seen, and I was prepared to die with a smile on my face and my head held high, just like the rest of them. Many of the people I was with had grown up in the Kurdish mountains and had been in combat training for years, which made them remarkable fighters. Though some were younger than me at the time (I was the grand old age of twenty-one in Kobani), most had already been in battle for many years. Life for many young Kurds in the Middle East doesn’t give you much: a Kalashnikov, a hatred of fascism, a love of freedom and memories of a loved one killed for the crime of their birth.

I had woken up that morning feeling sore, and went up to the roof of our house to find out what trucks the Turkish soldiers were letting through the border; again it looked as if they were letting drivers for ISIS through, while blocking ours. Kobani lies right on the border and our vantage point enabled us to see who was coming towards us. Using the scopes from our rifles, we would look hungrily at the truck drivers to see if they were coming to us. The passing trucks looked like they were bringing charity supplies to some of the thousands of refugees and those displaced by the conflict, but they weren’t – they were supplies for ISIS combatants. YPG units around Kobani followed the trucks and could see they were not going to the refugee areas. There were no refugee areas in Kobani; only combatants. We would watch ISIS fighters unload the vehicles and try on new camouflage gear sent over from Turkey. Supplies never came into our hands – only theirs. We knew this because the civilians were leaving the city through our areas; they didn’t go along the roads where the trucks were coming, because they knew these trucks were connected to the army of death they were fleeing.

I wondered at the time if the Turkish NATO soldiers noticed the same as we did, or if they let them go on purpose. Today I know the Turkish soldiers knew what they were doing. They didn’t let any Kurdish civilians from Kobani flee, but they let ISIS supply trucks through. We saw that the trucks contained food, dates and bread, and we were starving. Two days previously, Cengiz, a chef from Istanbul fighting with the YPG, had boiled together some leaves and grass with the final supplies of our sugar as a meal. Heval Amara and heval Bercem had a little taste of it and explained it was sort of like a dolma leaf, which is popular in the Middle East, and I tried it, initially thinking I enjoyed it. After a few mouthfuls, however, I knew it wasn’t doing me any good, but in lieu of other food I had to keep eating. Every night the conversation would be dominated by the amazing meals Cengiz promised to make when the supplies of tomato and potato arrived. We were hearing that the European countries were supposed to be sending weapons, but no one had any evidence of it yet. ‘Maybe the Europeans are sending some pizza and McDonald’s, when they send us those weapons,’ I joked. At times we became giddy with hunger and adrenaline, but when I made this quip I caught the eyes of one of the older men, who looked worried, and it made me stop laughing.

Our leadership was already well aware of the lack of weapons, and the poor state of the ones we had. But we, the YPG, refused to leave Kobani. As Kurdish fighters, we believe that freedom is more important than our individual small lives. We fight on regardless. The previous evening the Turkish volunteers sat with their mouths watering as Cengiz listed the best ways to sauté a potato or roast a tomato – I don’t speak Turkish, so Amara translated for me, until I asked her to stop. I resented having to learn Turkish; I am a Kurd, yet I have to learn the language that replaced Kurdish as part of a campaign of cultural and actual genocide. I know speaking a number of languages is a benefit, but Turkish is not my language and I found it hard to communicate with the others because of this.

There was a Swedish volunteer with the YPG, so he and I indulged ourselves by listing the foods we missed from Europe, while Bercem would tease us for our ‘Western imperialist’ upbringing and tastes, telling us the variety of food choices available within modern capitalist culture – what we call ‘the system’ – is absurd.

For the past three days and nights I had been sweating out some kind of fever, which made me annoying to sleep beside. None of the Kurdish volunteers were quite as sick as I was, which was embarrassing, and even the Swedish heval (how we fighting Kurds call each other – meaning ‘friend’ or ‘comrade’) – was holding up better than me, despite this being his first-ever time on the frontline.

I found Bercem after our morning assembly, drinking tea, and we discussed the mission to go and find some food, as incoming and outgoing fire boomed in the background behind us. We were in a constant state of alert for incomings and outgoings, and the threat of artillery attack was always near. We needed to stay rational and focused, and in order to do so we needed food. She urged me not to go, but I figured I’d rather be killed by ISIS than die of hunger from eating dirty old leaves. It was hard for me to see my comrades suffering, and we needed food before anyone else got sick. On missions, we go together in threes: when the YPJ and YPG are working together on missions, it is normally two YPG members and one YPJ, or two YPJ and one YPG. Every member of the YPJ is also a member of the YPG, but the YPG are not members of the YPJ: we are the female fighters only. Four of the guys volunteered to go with me, including the Swedish heval I had spoken to, but I kept looking straight ahead and stayed in line, as my commander picked the two who would accompany me: heval Cengiz, the chef, who at thirty-two was one of the oldest in our group, and heval Levant, a tall guy of twenty-three who mostly kept to himself. Both were Kurdish Turks from Istanbul.

We didn’t have a radio and were low on ammunition, but as I gathered my broken AK and prepared to leave, I felt determined but somewhat resigned. We had nothing to lose, and I didn’t really care if I died, because I knew we would all die if we didn’t eat. In Kobani, if you stayed in the same place for long, you would die: ISIS knew our spots and we were so close that at times we could hear them pray. It was early afternoon and the sun was high in the sky when we left, but I knew it would be cold later. I was always the wrong temperature in Kobani – shivering with the cold at night or sweating with a fever. We crept as quietly as we could between the houses, avoiding the main streets and obvious places where we thought ISIS might have a good vantage point.

The Chechens who had joined the ISIS forces were leading the march towards the city, and we knew one wrong move could put us in full view, so we kept low as we darted between the densely packed buildings. The structure of the streets and buildings gave us lots of places to hide, but made us more vulnerable to injury from debris. We knew they had shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles, which are basically point-and-shoot bombs that can destroy buildings, and really good-quality rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). Their weaponry was far superior to ours, looted from US-backed Iraqi soldiers who had abandoned their posts all over northern Iraq that summer, and it was the best in the Middle East at the time.

They had no allies inside Kobani, unlike other places, so we didn’t fear coming across families, and by this stage most of the civilians had left. Those who refused to leave helped the YPG, even though we asked them many times not to get involved. We informed them honestly about the great risks they would take by getting involved, but they wouldn’t hear of it. They would yell that they refused to leave the city of Abdullah Ocalan (our Kurdish nationalist leader and founder of the PKK political party) for the Turkish puppies, which is how they refer to ISIS. In the YPG, we call ISIS Daesh. We tried to stop civilians from joining us, but it was their decision to make; ours was to support them in clearing the Turkish puppies out of the city. It was for them that we fought.

The streets were quiet, save for the incomings we could hear in the distance. Being so close to Daesh meant this was a normal sound, nothing to fear. There was no one around; only abandoned cars, and confectionary stands emptied of their wares. The people had left in so much of a hurry that many of the doors we came across were unlocked. After the siege ended, Kobani was reduced to rubble, but as we walked around, it felt like a very beautiful ghost town, with us three as the apparitions.

Kobani was the first city to adopt the ideology of Abdullah Ocalan – the city is linked to Ocalan from the 1980s, when he lived there. We would not be giving up his city. Putting my finger on my trigger as I walked, I ventured slowly through the streets with the other two and we fell into a formation: Levant in front, me in the middle and Cengiz behind. I knew ISIS had thermal-imaging equipment, from my guard duty of standing watch on top of our building, whereas we barely had binoculars, so when night fell around 8 p.m. we discussed going home empty-handed.

‘We can’t venture much further,’ heval Cengiz warned, as we huddled inside the hall of what I think was an old newsagent’s.

‘We can’t go back with nothing,’ heval Levant said, which surprised me; he was quite shy, but the strength of his resolve was clear. They both looked at me expectantly.

‘Let’s just keep going,’ I said quietly, ‘but carefully,’ before telling them to lower their voices. We wandered into a more suburban area with no working street lights and walked silently, listening to the punctuation of gunfire from other areas of the city, the frequency of which rose steadily as the sun set.

We heard some gunfire around dusk coming from the east of our location, so we suspected the Chechens were making another evening advance. As we headed west, I rifled through my uniform, hoping to find extra ammunition. I didn’t know exactly where we were, as none of us were familiar with the city, but we figured we would take another route home now. We didn’t have the cover of darkness to protect us, and we were worried about leading enemy fighters back to our house, so we slowed down a little to let our eyes adjust to the twilight.

It was hard to tell at times whether the houses were half-built or half-destroyed, but I knew our fruitless search was becoming more dangerous, the further away from our base we ventured. I was beginning to accept we had been unsuccessful when suddenly a barrage of bullets rang out from the opposite side of the street. There had been rumours that the Chechen snipers had started using gigantic 23mm-calibre bullets. The deafening sound told me their cartridges were certainly more expensive than ours. Huddling as close as I could to the ground, I tried to identify the different arms being used: my initial hope that it was another YPG battalion out ‘hunting’ faded fast. They must have been tracking us, as they were extremely close and we were outnumbered, and in the panic heval Cengiz and heval Levant hid inside the different houses they were searching, while I dived down to the closest shelter I could see, a small confectionary stand on the street in between the two.

My first instinct was to return fire, but as I gripped my rusty AK, with my scarf still keeping my knife in place, and steadied my breath to prepare to shoot, I realized this wasn’t going to be possible. I had little ammunition and no vision, but worse than this, had I fired from my position I would have alerted the snipers to my precise location, which would bring them to me and the others. Trembling, I placed my hand on my heart pocket, where we all keep our final ammunition, in the event of being captured. The firing paused for a second and I ran towards the building closest to me. I knew this wasn’t smart; when a group shoots at you and then suddenly stops, they are probably waiting for you to make a move. But I had no choice – I had to move. It was either move or die.

Sure enough the shooting began again, and I felt my heart pound as the bullets flew close to my ears. I wasn’t thinking; I was in pure survival mode. Something took over and I managed to get to the building where heval Cengiz was. Entering the hall, I could hear him breathing heavily. It was difficult to see how badly injured he was in the darkness, but I could hear a gurgling in his throat, so I ran over to clear his airways. I couldn’t ascertain the full extent of his injuries, as we were both trying to keep as quiet as we could. I tried to stop the bleeding from his chest, but it was pumping out all over us both very fast. He was losing too much blood and I needed help to get him to safety, but I also had to check on heval Levant. I looked Cengiz straight in the eyes and said in a clear, hushed voice, ‘I will get heval Levant and bring him here, but you need to keep breathing, heval. We will leave together.’

Hearing a brief pause in the shooting, I ran the short distance to the next house. As I entered I could hear heval Levant moaning in the darkness. He was shot in the back through his shoulder and was panting loudly, but the noise was reassuring because it meant his breathing was okay. Hearing this, I realized that heval Cengiz was the more seriously injured, so I had to run back into the street to his hiding place. The shooting moved closer and was suddenly much louder and appeared to come from higher up, in frequent, erratic bursts. I raced as fast as I could, with bullets flying around me. I believed their new position put me outside their line of sight – as I couldn’t see them. I knew where I was going; they didn’t. So I just kept low, concentrated on my footwork and ran.

I reached the house where heval Cengiz was sheltering and was trying to calm myself so I wouldn’t make any mistakes, as there wasn’t time for that. Listening to the sounds of the gunshots to try and locate the snipers, I made my way towards heval Cengiz, who couldn’t walk and was barely breathing. He was too heavy for me to carry alone, and heval Levant couldn’t help carry him or support any extra weight as he was injured himself, although he could stand up and walk. Caught between these two injured men, I knew Daesh were making their approach. The shooting subsided briefly and I could hear the rough Chechen dialect of the soldiers ringing out behind me. I groaned so loudly that heval Cengiz noticed, as I could tell the soldiers were on the same side of the street as us, but that they had circled behind our building. None of us were in view, as we were inside the buildings and the firing had stalled, but I realized it was only temporary. They knew our positions and we had walked into their ambush.

I went slowly over to heval Cengiz, knowing that my movements could be heard. If he was going to die, let Daesh take us both. I would rather be with him and fight to the end – I didn’t want him to be alone. In our movement, we don’t leave each other, to save ourselves; we are one, and our strength is our unity. I knew he couldn’t shoot because of his injuries, but I still could, so there was a small chance we could make it out alive. When we say we fight for love and friendship, this is what we mean: we fight for each other.

‘Where is Daesh?’ he whispered gently to me with his broken Kurdish as I stood above him to hold his head in my arms.

I looked into his eyes and saw flecks of green I hadn’t noticed before. ‘They’ve stopped shooting and are close by. They are probably listening right now,’ I whispered as lightly as I could. I was kneeling right beside his ear, but I couldn’t afford to risk making a sound. He struggled to breathe and his eyes couldn’t focus on me. I could see the pale whiteness of his face as the blood drained out and onto the floor. Everywhere was wet and sticky. A pool began to form around us on the cold tiles, as we looked at each other again.

‘Bercho – go,’ he said to me. ‘Go see heval Levant,’ he insisted.

‘I have already checked on him,’ I whimpered, but he kept saying, ‘Bercho, bercho.’ He managed to look me straight in the eye, and I knew what he was telling me to do.

I scrambled out of the room to the doorway and paused for a moment before planning the journey back across the street. Although it was quieter, the risk now was that ISIS were waiting for me to leave the house – if they had, as I suspected, seen me run towards it. In war, mistakes equal death.

The unmistakable ping of a pin from an old Russian pineapple hand-grenade landing behind me interrupted my thoughts. It was like glass breaking. I turned round and threw myself to the ground as it exploded, because I didn’t know exactly who had thrown it. Initially I thought it was Daesh, but as I covered my ears and eyes while the debris from the building began to fall away around us both, I had a sinking feeling that it was my heval. Coming up for air seconds later, the smell behind me told me it was definitely Cengiz who had thrown the pin. He had placed the grenade in his mouth and blown his own head off. The smoke and dust from the settling concrete made it difficult to see what was going on, and I had to cover my face with a scarf to stop coughing. The smoke lifted to reveal a hole in the wall near his right shoulder. Cengiz was dead. There was blood everywhere, and he was not in one piece any more. The stench of his flesh caught in the back of my throat and I struggled not to vomit. Looking through the hole in the wall, I could see my escape. Looking back at Cengiz, I knew he had made the choice to kill himself to save all three of us from being captured. In my heart I had understood what he was telling me, when he had insisted that I go check on Levant. I knew the choice he had been contemplating: either one of us died or all three of us were captured and killed. These were the kind of impossible choices we made in Kobani.

I scrabbled through the remains of his body to find his ID card. The lower half of his body was exactly the same, his shoes were still neatly tied, but the top half was a gaping mess of yellow and red. It was only when I took his ID card that I learned his real name, instead of the nom de guerre we had known him by. From all over the world we fought together in Kobani, and Cengiz gave his life not only to save me and Levant, but to rid the world of the evil of Daesh. I wish I had known him better, but what he did for me describes who he was, and I remember him as a hero.

After racing back to Levant through the hole in the wall, we hobbled across the street towards where the firing had initially come from – but this was now in the opposite direction from the Chechens, as they had switched sides. Heval Cengiz had given us precious seconds, as Daesh had to retreat long enough for us to escape. I held Levant by the waist and we ran as fast as he could. Stopping in an alleyway, I was attempting to bandage his wounds using my jacket, as he had bled through his, when we heard another group in the street opposite ours. We both dived for cover, into the same house this time, but as the voices became clearer, it was Kermanji – the Kurdish dialect the YPG use to communicate – that we heard and not Arabic. Exhausted, I immediately shouted as calmly as I could for help. I could hear my voice shaking, as I emerged slowly from our alley to explain that we were lost, Levant was shot and we needed help to get back to our base. In the YPG we work in small self-sufficient groups, so because this group didn’t know us they half-heartedly went through our safety protocol motions; taking away our weapons, they checked our IDs and radioed our commander. Levant was given some pain relief and we were brought a small plate of food and some sweet tea, which was all I could manage.

Their driver, a young local guy from Kobani, drove us back, thanking us for coming and asking me questions about Denmark and Europe. Not in the mood to talk, I pretended my Kermanji wasn’t good enough to understand him and stared out of the open window, looking at the sky and thinking about Cengiz. In Kurdish we have the phrase ‘Sehid namirin’, which means ‘Martyrs never die’, and I repeated it over and over again, trying to let the final image I had of his corpse release itself from my mind.

We arrived back, debriefed our commanders and announced the death of heval Cengiz, and I went to the sleeping room to lie next to Bercem and Amara. In the yard below, one of those closest to Cengiz sang our martyrs’ songs gently throughout the night. In Kobani we always sang, and someone always played the guitar. Everyone was upset, but I was quite numb. The others were making an effort to talk to me, though, and I had a lot of questions about Cengiz: Did he have a family? Did he have a lover? Would his family be prosecuted, now that he was dead? Did he have a successful life? What did he give up for our movement? What did he give up for me? Would his family ever know what he had accomplished in Kobani? It’s unusual to see Turkish people joining the YPG, the Syrian Kurdish movement. It’s a rare act of solidarity between a Turk and a Kurd.

Food supplies eventually arrived the next day. We finally had those tomatoes and potatoes. ‘Heval Cengiz would have cooked us a feast,’ Bercem said quietly as she was tasked with providing the food for our tabur that day and I helped her prepare. I threw up my food after eating that first day; and my shit, which up until then had been green, was completely black. Something was seriously wrong.

Levant, injured to the extent that he could no longer shoot, was smuggled out of Kobani on the same lorry that had brought our paltry food supplies, and crossed the border into Turkey as a civilian. I have not seen him since. I hope the Turkish state doesn’t jail or execute him for fighting with the YPG against Daesh. The next day, after Bercem’s cooked breakfast, I was summoned to a meeting with my YPJ commander, who told me it was time for me to leave the frontline and Kobani. It was impossible for me to think about leaving when I was there; as far as I was concerned, there was no such thing as life outside the siege. I didn’t want to go and tried to refuse, but she said I could go to either Turkey or Iraq: my stomach had swollen up and I needed to see a doctor. I could return afterwards, she promised.

I travelled back through our base in Rojava, our area in northern Syria, and made my way into Iraq. I slept for almost the entire journey, curled up in the back of a truck that seemed to operate as a taxi service for local farmers. Hidden under a pile of blankets as I crossed the border, I slept and sipped my bottle of water, feeling sick, sore and delirious.

Arriving in Erbil, I had a few days of sleeping in a bed and being served food as I rested. I went to the doctor’s, but didn’t tell them where I had been or what I had been doing, as I didn’t trust them. I just told them I was visiting from Denmark and wasn’t feeling well, after eating something that didn’t agree with me. Which wasn’t a lie. Though I felt like a failure at the time, being sent away from Kobani saved my life, as I missed the terrible winter that followed that starving summer. Friends of mine who survived there until the end say it wasn’t until the start of winter that they began to call Kobani our Stalingrad, but it’s hard for me to imagine how life could have become more difficult.

In Erbil I knew I was lucky to be alive, but I was sick with worry for my friends who had remained, and I felt this cloud of guilt and shame descend on me that I just couldn’t shake. Cengiz was the last person I saw die in Kobani, but he wasn’t the only person I lost in that fight. Girls as young as fourteen and boys as young as twelve died in that battle; this is not our policy in the YPG, but how could we stop them fighting for their lives?

As I recuperated in Erbil, every day on social media I would read reports from different rumour mills, and new martyrs’ pictures made by the YPG would be posted in tribute to those who had died. I became fearful of checking online, as I didn’t want to see who had died. But of course I had to know. I went online every single day, and frequently. I think this was when I first became addicted to social media, as it was my connection to my friends. Our tabur, called Tabur Berivan, was demolished – pushed back by Daesh, cut off by Turkey and undermined by the glacial speed and infighting among the international coalition.

In the darkness of Kobani we eventually defeated Daesh, despite the best attempts of Turkey to prevent us. By January 2015 we had cleared it of their black flags and dark hearts. We lost more than 1,000 fighters in Kobani, though the official death-toll reported in the international media was much lower. It was the first major battle that the YPJ contributed to, with a bravery the world hadn’t seen from our army before. We fought fearlessly, along with the men, and accounted for about one-third of the fighters, but more than one-third of the deaths. For the women of the YPJ, it was not only about defeating Daesh, it was also about creating a new society in the Middle East, with new laws and cultures that value and respect women as equals. Many of the girls I fought with died for this, and several fighters – like Cengiz – blew themselves up in order to save their friends.

Shortly after I left Kobani, Arin Mirkan, who was a mother of two, committed suicide when her group was surrounded on the hill of Mistanound. She did this to save her friends. Her explosion allowed the other girls to escape when they were completely surrounded, and her tabur survived because of her heroism; she was their commander, and she died so they could live. These deaths are not our methods as YPG fighters, and the difference between us and Daesh is that they fight in this way to die for a promised paradise with glory and greed, but we fight so that others can live under our own democratic terms. The heroic act of Arin, and many like her, is the symbol of true friendship, which is everything in our movement. She valued the love of her friends more than her own life. That’s why we say, ‘Sehid namirin’ – ‘Martyrs never die’ – because the memory of them will live on for ever. They are the reason we are still here.

Those who ran out of ammunition were less lucky and were captured by Daesh, who tied their hands together and lashed them to the back of a car, then drove them through the city. It was a brutal public execution, and the civilians cheered – most likely because of fear, but it was an ugly thing to see.

I spent just over two weeks in that filthy old house in Kobani, and three years later my body is still recovering from what happened. Of the fifteen of us, only five from my Tabur Berivan of YPJ and YPG survived. I am the only YPJ fighter from my unit who made it out alive. For this I take absolutely no pride. I’m supposed to be one of the lucky ones, because I survived.

I’m still here, breathing the air of freedom that my friends gave their lives for, and I want to use my voice for those who lost theirs: the many hundreds of young Kurdish volunteers from Bakur (Turkish Kurdistan) who swam across the river, risking their lives on the way to the city that would become their grave; those who fought for love and friendship, and whose names will never be known. Even though press from all over the world were watching us, they didn’t really see what was actually going on. They were recording us on their cameras like they were shooting a film, and we could see them looking at us and doing nothing to help. They were so close we could see them without binoculars, but they weren’t as close to us as we were to Daesh.

Those watching us through the lens of their cameras could hear the bombing and shooting from the safety of the blockaded border, while I was hearing the screams and calls for help from my friends. They saw burning buildings, but my view was different: I watched the burning bodies of my friends.

CHAPTER ONE

Daughter of the War in the Desert

If Kurdistan was a country, it would be one of the most populous states in the Middle East, with thirty million people scattered between Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Azerbaijan. This is just the official toll, the real number is believed to be as many as fifty million. Turkey and Iran refuse to acknowledge their Kurdish populations, and therefore don’t count correctly the number of Kurds living within their borders, so it’s hard to know for sure how many we are.

My family was originally from the eastern part of Kurdistan, in the western part of Iran, which we Kurds call ‘Rojhelat’, meaning sunrise. In the YPG, our area in northern Syria is the western part of Kurdistan and we call it ‘Rojava’, meaning sundown. In Kurdish we also use the words Rojhelat for east, and Rojava for west. Bakur, our northern area, means ‘north’ in our language, and geographically is situated in south-east Turkey. Bashur, our southern area, is in the northern part of Iraq and we use this word for south.

Most Kurds speak Kermanji, which is spoken in Bakur and Rojava. Some Bakur Kurds still speak the original Kermanji, called Zazaki, but also different dialects, such as Sorani, Badini, Feyli, Kalhuri and Hawramani, which are also spoken in Rojhelat. Originally my family spoke Kalhuri, but now we speak Sorani or a kind of pidgin-mixture of both. Because of the different dialects, it’s pretty common for Kurds to struggle to understand each other.

My grandparents are both children of the Mahabad Republic, the first and only independent state declared by the Kurds in January 1946, and destroyed by the Iranian regime in December that same year. Along with their parents, my grandparents supported the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) when it was formed the year before. As the first Kurdish armed movement to become an official political party, the PDKI was established to promote democracy, social justice and gender equality, rejecting monarchy, theocracy and autocracy. Supported by the Soviet Union, the PDKI ran our republic for the five years leading up to the official declaration in 1946. The PDKI continue to train Peshmerga (our word for fighter, which translates as ‘one who stands in front of death’) to defend Rojhelat from the Islamic regime of Iran. After our nation was destroyed by the Shah of Iran in December 1946, many PDKI leaders were executed, but the party remained in existence. My grandfathers met while my family was still inside Iran, as they both served as Peshmerga fighting against the regime of the Shah in 1967. This is how my mother and father would later come to know each other.

My mother’s family farmed the mountains outside Kermanshah in the countryside of Serpeli-Zahab, which is right on the border with Iraq. Even within this small region there are several dialects: Kermanshani, Kalhuri, Sorani and Feyli. Working as an informal cooperative, her family produced food and reared animals to trade. My mother didn’t go to school in Iran or Iraq – her education comes from Denmark. My father believes the lack of women’s education is one of the reasons why Kurdistan still doesn’t have its own nation state, and he was educated very well by his family along with his brothers in Iran, but his studies were cut short by the war. All of the sons in his family, just like my mother’s, became Peshmerga as soon as they were old enough. This led to several relatives and friends being executed and killed inside Iran, so my father had to leave.

While my father’s family is mainly Sunni Muslim, one of his brothers was a Christian – which didn’t bother his family, but made him even more of a target for Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. He would sneak around to attend services run by the American Church groups that existed inside Iran. He was abducted many times, but he could not confess to crimes that he had not done, so his captors would eventually grow tired and release him. They tortured him because he was a Kurd, first and foremost, but also due to his belief in a Christian God and their belief that he was an agent of ‘the Great Satan’ – America. Kurds are mainly Sunni Muslims, and the regime remains a Shia theocracy. To be a Kurd in Iran at the time – male or female – was to be an enemy of the state, and to be Sunni inside Iran still remains very difficult.

My mother’s father was a Peshmerga commander and captain for the former president of Bashur, Mala Mustafa Barzani. He was also a farmer, who would take animals to trade in the markets inside the old souks of Kermanshah, our city in Iran. Our area, also called Kermanshah, has the highest Kurdish population in Iran and extends far beyond the city, almost from the city of Hamadan towards Tehran, and to the border with Iraq on the other side. It is home to Shia and Sunni Muslims as well as Circassians and Christians, which makes it unique as a region inside Iran. Although the city suffered in the Iran–Iraq wars during the 1980s, the people of Kermanshah are relatively open-minded for the Middle East. Different cultures live peacefully together, as they are all threatened by the regime. Young people especially look west for their hopes for the future – devouring American media, fashion and popular culture – or at least the ones I know do.

My mother thinks she was eleven when her family fled on foot from Iran into Iraq. As she never went to school or learned to count, she isn’t even sure when she was born: she thinks it was 1971. She has a very conservative view of how a family, and especially women, should be. She married my father when she was fourteen years old, in a match arranged by my grandfathers, who met again when their families were both living in the Al-Tash camp in Ramadi, after they fled Iran.

Marrying young remains very normal in my culture, and in my family. Back in my mother’s day – which is not so long ago really, as she is not yet fifty – girls would be married as soon as they had their first period. My mum used to say it was for our own sake, because waiting longer would mean a girl was more likely to have physical contact with a man, which, in my mother’s opinion, is a fate worse than death. As our mother, it is up to her to police our sexuality and ensure that we protect the family name until we are married. The younger this happens, the better. I am twenty-five now, and my not being married is a source of discomfort for my family. We talk a lot about girls in our community, and as a girl gets older and remains unmarried, rumours about her start. People look down on her, and talk badly of her mother for not being ‘woman enough’ to raise girls properly. Everything we do right, our father takes the credit for, but for everything we do wrong, our mother takes the blame.

A woman being independent, or living alone, is treated suspiciously by the community. After a certain age – normally late teens or very early twenties – marriage prospects for girls like me shrink, and offers of marriage start coming in from older, divorced or disabled men; those with lower status. If you are unmarried after twenty-five, in the community I grew up in, most likely your fate is to stay unmarried or to become a man’s second wife or mistress. In the Islamic world it’s estimated that one in every five men practises polygamy, and sadly many men in Europe practise it, too. If, like me, you are not a virgin, your prospects are worse still.

In the 1980s, when my mother was growing up, the Iran– Iraq war was fought mainly in Kurdish areas, and villages all along the border were destroyed by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist party soldiers, who suspected the villagers of being traitors to the Iraqi government, or loyal to Iran. Hussein was a dictator who fought against anyone who wasn’t a Ba’ath supporter. During the disaster of the wars, our neighbouring countries supported different Kurdish armed movements, and different tribes aligned with them in return for food, supplies, shelter and protection. This led to different Kurdish factions fighting each other, and although the conflict between Iran and Iraq eventually stopped, their wars against the Kurds never did. The Iraqi border with Iran became porous, as Iranian Kurds (from the PDKI) brought supplies over the mountain to fight against Saddam, and other Peshmerga fighters from Iraq (from the Kurdish Democratic Party, known as the PDK) used the borders to fight the regime of Iran. Many of the Kurds living near the border were nationalists against the Ba’ath party and Saddam, but were also opposed to the Islamic regime of Iran. My family, like many in the region, was against them both. Thousands of Kurds fled from Iraq into Iran, but going back to Iran, as supporters and members of the PDKI, was not an option for us.

My family name, Palani, has long been associated with the PDKI, and still is. After living in Balkan camp near Sulaimaniya in northern Iraq, both my father and my mother were moved, with their families, by an NGO to the Al-Tash camp near the desert in Ramadi, in the centre of the country. Some of my father’s family were moved south from Balkan to Halabja, and lived there from 1987 until the 1988 attacks.

On 16th March 1988 Saddam Hussein’s forces dropped chemical bombs on the city of Halabja, killing thousands of civilians. More than 5,000 people were poisoned that day, and many more died as a result of their injuries in the months and years that followed. It is the greatest crime ever inflicted on our community, and remains the biggest gas attack ever launched against a civilian area. Halabja was not the only gas attack against members of my family, but it was the most personally devastating, as many of our immediate relatives died: thirty family members in all. My maternal grandmother lost her entire family. We have only one picture of my aunts who died, from when they were younger girls with my grandfather in Iran. We don’t have any pictures of their children or family, so I often wonder when I see the famous images of the attacks if the bodies of the children I am looking at are the remains of my relatives. I will never know.

My mother had me quite young, but before me she had my three brothers and one of my sisters. My mother had all her babies in Ramadi: six in total. Two years before I was born, in 1991, things became more difficult for my family, as we had taken part in another failed uprising against Saddam Hussein. My father worked as a pharmacist, but like all Peshmerga, he helped the American soldiers when the Iran–Iraq war turned into the Gulf War in 1990.

Working with the Americans was a political pivot for my grandparents, as the Soviet Union had previously been our allies supporting the Mahabad Republic, and we were now aligning with US forces; but, as Kurds, we are not afraid of making strategic alliances against our enemies. As Kurds, we are targeted by the countries within whose false borders we live: Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran; and by their strategic backers. After Halabja, Saddam Hussein was our common enemy and we got help from the USA to depose him.

My father speaks five languages, having benefited from his education in Iran under the Shah, and worked with the USA to help the soldiers with logistics, translation and supplies in Iraq. When the Americans originally came to Ramadi they had not expected conditions to be as desolate as they were, and they were forced to leave again so that they could plan properly for a bigger operation. My father managed supply routes for them and spent some time working as a translator. He speaks with an American accent when he talks English, as many Kurds do. The US soldiers would guard our camps so that Saddam’s soldiers couldn’t come in, and their combat medics would give basic treatments to those in dire need.

The Americans promised that a Kurdish region would be established in Iraq after Saddam fell, so naturally many Kurdish men joined up to secure this and to avenge our dead. But the Americans lost the Gulf War – they left in 1991 with Hussein still in power – and when they suddenly left Ramadi, our camps were attacked. We were on the retreating side and, as punishment for working with the Americans, we were again targeted by the regime. Around this time our camp in Ramadi suffered an attack, and my older brother Mariwan was killed due to the lack of medicine and treatment provided for our people from the hospital in Baghdad. Lots of our people died; from bad medicine, from no medicine, but mainly from the regime’s attacks.

My brother was two years old when he died and was buried in the desert along with the others who were killed. Neither my mother nor father talks about him. The trauma of his bloody death lives on in both their hearts, and my mother places this event as the moment their marriage began to disintegrate. I’m not sure. I’ve only really seen my mother hysterical once in my life, and it was when one of my two surviving older brothers got sick. She screamed at my father and said that if another of her sons died, she would go with them and he would be left with us. Mariwan was named after a Kurdish city in Rojhelat, but in our family everyone called him Rambo, because he was very big when he was born, with white skin and black hair. There was one old TV in the camp, where we would watch American films huddled together, and Rambo was everyone’s favourite show. Mariwan was supposed to grow up to be a warrior, like our father and grandfather.

A few years after my brother died, on 22 February 1993, I was born. My mother said I arrived at first light on another freezing-cold day. I was named Hero Palani – a Kurdish name, but also after the Greek goddess Hera – by my father, but my beloved Christian uncle Jabbar changed my name to Joanna, which means ‘beautiful’ in Kurdish. I remember more from Ramadi than my siblings, but within our family there is endless debate over whether we actually remember events or just think we do, because we know the story behind the photograph. Old photographs are a particularly valuable commodity in my family: both my parents jealously guard pictures of their family and their childhoods in Iran, and then of ours in Iraq. There is a certain preciousness to our photographs; spread out as we are, and destroyed by such an array of enemies, these pictures are often the only evidence we have of our relatives and our past. In Kurdish culture we celebrate the group – the family, the community and the clan – instead of the individual, and the rules of the clan are the rules by which we live. The pictures of my family in Ramadi show us all huddled in a big tent. Inside, almost a whole wall of our tent is taken up with coloured blankets, and some of my earliest memories of Ramadi are playing on these blankets and looking up at the sky.

My father, uncle and I are the only ones who remember the Ramadi camp as it really was, for the rest of my family have these weirdly romantic memories of our lives there. I remember it as a dry and dirty place, without much food or water. I would accompany my older siblings and other relatives to dig for water in the sand. Because it’s in the desert, Ramadi scorches in the summer and freezes during the winter. We would be sent to bed with gloves and hats on inside our tents, and if we complained of a chill we would be allowed to sleep in between my mother and father, along with my youngest sister, who in my mind was permanently attached to my mother’s chest. I’ve never learned to sleep properly, and my memories of bedtime are of lying shivering in between my parents, or trying to find some relief from the oppressive heat. Many infants died from pneumonia and hypothermia in Kurdish camps around this time; it’s hard to know how many, as we are not the kind of community the regime was interested in recording, and we would never trust them to keep count accurately anyway. Because of the lack of medicine, vaccines and healthy food, my siblings and I suffered from malnutrition. We had those big stomachs you see on television, where the swelling was caused by not having enough protein in our diet – a condition known as kwashiorkor.

I was too young to go to school, so I stayed with my mother and my baby sister as our older brothers and sister went for lessons. They had to walk to school from our tent in single file, with one standing in front of the other with a branch, so that if they came across a landmine, only one of them would be killed. When my brother and sister went to school, my mother would sit in the front of our tent and fix her hair and inspect her face, using a tiny pocket mirror that she would hold up to the light. She would always become very annoyed if we got dirty, and once we were washed we were expected to stay clean for as long as possible. Water was a precious commodity, so we weren’t allowed to wash too frequently.

My older sister would collect sticks from ice-cream lollies from around the camp and we would transform them into dolls, and build them houses and furniture from the rubbish that we found in the sand. We had many cousins and family members across the camp, so we would sometimes spend the day or night with them in their tents or houses. Behind the tents the boys would play football, making a ball from different plastic bags fashioned together – the older boys managing to copy the stripes of a leather ball surprisingly well. The women built ovens to prepare the bread daily, and dug deep holes in the sand for water. Every night everyone would gather around the TV to watch the news. Although the camp had two entrances and exits, us Kurds shared with the Shia families, and we all lived together.

Saddam’s soldiers were called ‘the redheads’ because of the berets they wore as they stomped around our camp. After the Americans left, they would come in whenever they felt like it, and my aunt would tell us kids to run and hide inside our tents. Our Peshmerga had no weapons in the camps, so we had no choice but to agree to whatever the soldiers demanded. They of course targeted our women, raping them with absolutely no consequences to themselves. In the Middle East, most people consider a girl able to have sex as an adult after she has had her first period. A ‘woman’ is normally a married person who has had sex, whereas a ‘girl’ has not had sex. The redheads would take any girl they wished, and they did so often. The girl was sometimes taken away from her family and never seen again – trafficked into prostitution or killed – or was returned to her family after the rape, so that the family would be destroyed by the shame. Either way, the girl’s life was over. In a war created by men, the girls are sacrificed.

After the Americans had left, leaving the camp open to attack from Saddam, the military bases and medical hospitals all packed up and left; it was only the NGOs that remained. Suddenly everyone was trying to leave the camp, in case the redheads came back again. There was fear that the first bombardment was just a precursor to a second attack, and that they were planning to gas us alive. We had no gas masks of course, but my parents taught us how to cover our faces and ears with our clothing.

The United Nations helped my family apply for asylum to leave Ramadi, and suddenly, in 1996, we were told we were going to Denmark, as UN refugees. We got to leave more quickly than other families because of what had happened to Meriwan, but my aunt was not allowed to travel with us at the time. I remember three big buses coming to collect us and several other families who were going to Scandinavia. The women who were staying behind sobbed as we boarded the buses, and the crowd was so big that the bus driver got annoyed at everyone hugging each other through the open windows. My mother tells me that she held up me and my little sister at the back of the bus, so that my aunt could look at us one last time through the window, and then held me and cried into my coat until we arrived at the field where the plane was. She talks about our aunts a lot, and we remain close to them when we travel back to Kurdistan. Today I’m closer to my family in Kurdistan than to my immediate family here in Denmark.

On the plane I have vague memories of sitting beside the window and being high in the air, above our camp, and flying away from Iraq. There were many children running up and down the aisles, but my parents made us sit still in our seats and hold hands. We sat pinned down into our seats with big seatbelts across us, until I fell asleep looking out of the window.