11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

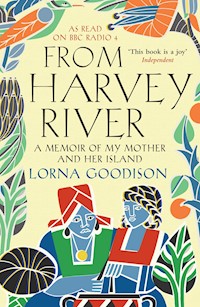

As read on Radio 4, an irresistibly joyful memoir of mothers and daughters, and the importance of home. Lorna Goodison's family made their home in the Jamaican village to which her great-grandfather gave his name: Harvey River. Her mother Doris was a big-hearted lover of big stories and raised Lorna on tales of their family's - and Jamaica's - history. Gorgeously written with unashamed joy, From Harvey River weaves together memories with island folklore to create a vivid and irresistible story of mothers and daughters, family, and the ties that bind us to home.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

From Harvey River

Lorna Goodison is a poet, author of eight books of poetry and two collections of short stories. Her work has been widely translated and anthologized. In 1999 she received Jamaica’s Musgrave Gold Medal. Born in Jamaica, Goodison now teaches at the University of Michigan. She divides her time between Ann Arbor and Toronto.

Copyright

First published in Canada in 2007 as From Harvey River:

A Memoir of My Mother and Her People by McClelland & Stewart, Ltd, Toronto, Ontario.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Lorna Goodison, 2007

The moral right of Lorna Goodison to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders.

The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-843-54996-3

Contents

Cover

From Harvey River

Copyright

Prologue

part one

part two

part three

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

To Doris and Marcus

Prologue

Throughout her life my mother lived in two places at : Kingston, Jamaica, where she raised a family of nine children, and Harvey River, in the parish of Hanover, where she was born and grew up. Harvey River had been settled by her grandfather William Harvey, who gave his name to the river, and the river in turn gave its name to the village. I do not think that there was ever a day in my childhood when the river or the village was not mentioned in our house. Over the years Harvey River came to function as an enchanted place in my imagination, an Eden from which we fell to the city of Kingston. But over time I have come to see that my parents’ story is really a story about rising up to a new life. As a child I constantly asked my mother about her life before, as she put it, “things changed.” I listened carefully to her stories, and repeated them to myself. I also took to asking urgent questions of my father. I have an image of me standing outside the bathroom door calling in to him over the noise of the shower, “So what was your mother’s name, and what was her mother’s name?” But my father’s people do not live long, and he died when I was fifteen years old. So I never did get to ask him all my questions. After my mother Doris’s death nearly thirty-five years later, I began to “dream” her, as Jamaicans say, and in those dreams I continued to ask her questions about her life before and after she came to Kingston. And then there was this one very vivid visitation when I dreamt that I went to see her in her new residence, a really palatial and splendid sewing room with high stained-glass windows, where she was now in charge of sewing gorgeous garments for top-ranking angels. She said they were paying her a lot for her sewing in this place, and that all her friends came to talk angelic big-woman business with her there as she sewed. She said she could not tell me more as she did not want me to stay with her too long, because the living should not mix-up too much with the dead. But as I was leaving the celestial workroom, she handed me a book. This is that book.

part one

The baby was plump and pretty as a ripe ox-heart tomato. Her mother, Margaret Wilson Harvey, gently squeezed the soft cheeks to open the tiny mouth and rubbed her little finger, which had been dipped in sugar, back and forth, over and under the small tongue to anoint the child with the gift of sweet speech. “Her name is Doris,” she said to her husband, David.

In later years, my mother preferred to spell her name Dorice, although in actual fact she was christened Doris. But she was registered under a different name altogether – Clarabelle. This came about because of a disagreement between her parents as to what they should call their seventh child. Her father, David, was a romantic and a dreamer, a man who loved music and books, and an avid reader of lesser known nineteenth-century authors. He had read a story in which the heroine was called Clarabelle, and he found it to be a lovely and fitting name. He told his wife, Margaret, that that was to be the baby girl’s name. Well, Margaret had her heart set on Doris, because it was the name of a school friend of hers, a real person, not some made-up somebody who lived in a book. Doris Louise, that was what the child would be called. They argued over it and after a while it became clear that Margaret was not going to let David best her this time. He had given their other children names like Cleodine, Albertha, Edmund, and Flavius. Lofty-sounding names which were rapidly hacked down to size by the blunt tongues of Hanover people. Cleo, Berta, Eddie, and Flavy. That was what remained of those names when Hanover people were finished with them. Margaret had managed to name her first-born son Howard, and her father had named Rose. Simple names for real people.

There was nobody who could be as stubborn and hard-headed as Margaret when she set her mind to something. She was determined that her baby was not going to be called Clarabelle. “Sound like a blasted cow name,” she said. David gave up arguing with his wife about the business of naming the pretty-faced, chubby little girl, especially after Margaret reminded him graphically of who exactly had endured the necessary hard and bloody labour to bring the child into the world. He dutifully accompanied her to church and christened the baby Doris, on the last Sunday in June 1910. Then the next day he rode into the town of Lucea and registered the child as Clarabelle Louise Harvey, and he never told anyone about this deed for fifteen years. As a matter of fact, he is not known to have ever told anyone about it, because the family only found this out when my mother tried to sit for her first Jamaica Local Exams, for which she needed her birth certificate. When she went to the Registrar of Births and Deaths, they told her that there was no Doris Louise Harvey on record, but that there was a Clarabelle Louise Harvey born to David and Margaret Harvey, née Wilson, of Harvey River, Hanover. She burst into tears when she heard what her legal name was. “Clarabelle go to hell” her brothers chanted when the terrible truth was revealed. Not one to take teasing lightly, she told them to go to hell their damn selves.

Eventually her name was converted by deed poll to Doris. Thereafter, she signed her name Dorice, as if to distance herself from the whole Clarabelle/Doris business. Besides, Dorice, pronounced “Do-reese,” conjured up images of a woman who was not ordinary; and to be ordinary, according to my mother’s oldest sister, Cleodine, was just about the worst thing that a member of the Harvey family could be.

Cleodine was definitely not ordinary. She held the distinction of being the first child to be born alive to her parents, David and Margaret Harvey. She emerged into the world on January 6, 1896, as a tall, slender baby with a curious yellowish-alabaster complexion. The child Cleodine immediately opened her mouth and bellowed so loudly that the midwife nearly dropped her. Before her, not one of the five children conceived by Margaret had emerged from her body alive. Every one had turned back, manifesting themselves only as wrenching cramps, clotted blood, and deep disappointment.

This time around, her husband, David, had watched and prayed anxiously as Margaret’s belly grew big with their sixth conception. Would this baby be the one to make it? Would it be the one to beat the curse of Margaret’s seemingly inhospitable womb? The doctor had ordered her to bed the day it was confirmed that she was again pregnant, and once this happened, her mother, Leanna, had announced that she intended to mount upon her grey mule and gallop over to Harvey River each morning to take care of her daughter. Leanna forced her to lie still for most of the nine months, forbidding her to go outside, even to use the pit latrine. Instead she made her use a large porcelain chamber pot which she herself emptied. She bathed her daughter like a baby each morning and combed her long hair into two plaits, pinning them across her head in a coronet. She prepared nourishing invalid food and fed her steamed egg custards and cornmeal porridge boiled for hours into creaminess and sweetened with rich cow’s milk. She made her thyme-fragrant pumpkin soup and fresh carrot juice, because Margaret’s cravings were all for golden-coloured foods, which she ate sitting up in her big four-poster mahogany marriage bed. Another reason for feeding her these soft foods was that Margaret had become afraid that any abrupt, jarring movement might dislodge the foetus. She chewed upon these soft foods slowly and gently, and later, to occupy herself she sat propped up in bed quietly stitching and embroidering every imaginable type of garment, except for baby clothes.

After Leanna departed each evening to return to the arms of her husband, John Bogle, David sat by Margaret’s bedside and filled her in on what was happening in the village. He read to her from the newspapers or the Bible, and then he retired to the adjoining bedroom to sleep alone. Margaret and he had both agreed that nothing, not even their much-enjoyed conjugal lovemaking, should endanger the safe delivery of this child. David, who was an extremely private and modest man, had to bear with his mother-in-law, Leanna, saying the same thing to him each evening before she left: “Remember Mas D, no funny business tonight.” And David, who believed that all such matters were truly private, would flush and say to his mother-in-law: “Don’t worry about me and my wife’s business.”

For every one of those turned-back births, Margaret had prepared elaborate layettes. David had even bought an ornate, Spanish-style christening gown in Cuba the first time that she had become pregnant, a gown which they had given away in despair after they lost child after child. This time she was determined that she would prepare nothing for this baby just in case. Just in case fate had decided to insult her once again, she was preparing to insult fate first. See, she would say to fate, I never expected any baby to be born alive, because I never even prepared any baby clothes. Not a small sheer poplin chemise or a soft white birdseye diaper. Not one woollen bootie did she knit or crochet, not one bootie the length of her index finger. No beribboned bonnet big enough to cover a head the size of a grapefruit; nothing. She had given away all the clothes she had made for her lost babies. Then one year later she found out she was pregnant again, but this time she was prepared for the worst. She would take to bed and chew gently, yes, but not one garment would she make in case she lost this baby too. Not one garment would she make, but every time she had such a thought, the foetus would deal her a swift kick from inside the womb. It was as if the baby Cleodine wanted to step out and occupy her place in the world immediately, because hers had been nearly a breech birth. However, the midwife succeeded in persuading her to come in headfirst, and she crowned promptly at 6 a.m., then shouldered her way out, announcing her presence with a commanding bawl.

“Oh my God, look Missus Queen,” was what Margaret said when she saw her first-born, because the baby bore an amazing resemblance to Queen Victoria. When the news went out through the village that a baby girl had broken Margaret and David Harvey’s bad-luck-with-children cycle, the Harvey relatives came calling. Many of the women arrived bearing beautiful garments they had sewn in secret because everyone in the village knew of Margaret’s attempt to disarm fate by refusing to prepare for this baby. They brought exquisitely embroidered baby dresses, dozens of gleaming white birdseye napkins already washed clean in the Harvey River and dried near the field of lilies. They brought knitted woollen caps and booties, mostly in white and yellow, not pink or blue, because nobody wanted to go so far as to predict the sex of the baby that the whole village all but fell down and worshipped. Born to rule, the little girl Cleodine was hailed as a “Duppy Conqueror,” a mortal who triumphs over the baddest of ghosts, because she had cleared all the killing spirits out of her mother’s way.

First-born children set the pace; they are the engine of the sibling train, the source of authority, inspiration, and energy for all the brothers and sisters who follow. The first child in a family must be raised to be bold, ambitious, strong and confident, the example for all the other children coming behind. Or so Margaret and David, like many parents of that time, believed – that the first child in a family was undoubtedly the most important one.

For the first year of her life, Cleodine’s long narrow feet did not touch the ground because someone was always holding her aloft, showing her off to admiring strangers. Look she was born with two teeth, look she had nearly a full mouth of teeth before she was eight months old, look she is obviously bright, very bright. Look at her eyes, amber brown like a tiger’s eyes, and those extraordinary fingers, like those of a piano player. The child often waved them like the conductor of an orchestra.

Maeve, Queen Maeve, was what Margaret’s father, George O’Brian Wilson, had wanted to call his first female grandchild by his favourite child, Margaret. Queen Maeve the powerful mythical Celtic queen. But David said no, and put his foot down. He would name his first child, he and he alone. Yes, she would be named after a queen, for she was a queen and he toyed with the idea of calling her Victoria. But secretly he was hoping that the child would grow out of her resemblance to Queen Victoria, who, let’s face it, was not a pretty woman.

Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. A beautiful woman, powerful enough to mesmerize King Solomon. That would be the child’s name. When he told Margaret that the baby’s name was Cleopatra, he lowered his voice and said, “Cleopatra, we can call her Cleo; my Cleo, Cleo mine.” Margaret looked at him and said, “Cleo Mine or Cleo Thine?” And they liked the sound of that and called the baby Cleodine, who proceeded to grow up and rule over everybody in Harvey River as long as she lived there.

Two years after the triumphant entry of Cleodine into the world of Harvey River, Margaret gave birth to another baby girl. In what would become an act of prescience, they named the girl Albertha. Having produced a healthy and intelligent child in the form of Cleodine, Margaret was a little more relaxed about giving birth the second time around. She did not take to her bed as she had done when she was carrying Cleodine, but she was completely convinced that if she was going to bring this baby to full term she would have to behave as seriously as possible for the duration of this pregnancy. If, in her mind, hard-chewing had posed a danger to the safe delivery of Cleodine, then she decided that mirth, laughter, frivolity, these things would surely serve to place harm in her way. Again, she had not made any clothes for this baby, but this time it was not because she was trying to pre-empt fate, this time she had no need to prepare baby clothes because Cleodine had been showered with so many beautiful garments by the overjoyed people of Harvey River that this second baby would always be able to wear her big sister’s gorgeous outgrown dresses.

Everybody called Albertha “Miss Jo” from the day that she was born. Perhaps they called the small girl “Miss Jo” because there was an absence of anything jovial about her grave, unsmiling little presence. The baby seemed to have absorbed her mother’s fear of joy as a dangerous force while she was in the womb, the same fear that caused some Jamaicans to quote proverbs like “Chicken merry, Hawk near” to people who seemed overly happy. The truth was that Margaret and David had been hoping for a boy. Nothing would have made them happier than the birth of a male Harvey, so while there was some rejoicing at the safe delivery of this second child, alas, Miss Jo was not destined to be a star like Cleodine, who, when taken into her mother’s room to view her sister, immediately said: “I big, you little.” Albertha grew into a fair-skinned, always inclined-to-stoutness girl of medium height. Her outstanding features were her broad, high cheekbones, and her dark eyes, which could have been described as lovely if they did not perpetually seem so sad. From very early in her life she displayed certain prudish tendencies which made it quite clear that she did not enjoy the rude and rustic ways of country folk. She was pious and chaste and she never laughed at the smutty jokes involving the sex life of animals in which country children took delight. The rude, suggestive words of Jamaican folk songs did not cause her to giggle, like they did other small children.

Gal inna school a study fi teacher

bwoy outside a study fi breed her

Rookumbine inna you santampee, rookumbine …

No, such songs did not cause her any amusement whatsoever. Her presence was a check on any loud-laughing, rudejoke-telling gathering. She was forever declaring that such and such a person was “too out of order,” forever complaining to her parents that one or the other of her siblings had transgressed in some way. All dancing, except maybe a stately waltz, was nothing but coarse slackness to her. She passed her time mostly reading and doing elaborate embroidery, for which she developed a great talent. This was the one area in which she grew to outstrip her older sister, a fact that greatly angered the competitive Cleodine, but which caused Miss Jo to ply her needle the more to scatter lazy daisies and raise up padded petals of roses across the surface of tray cloths and doilies, even as she looked with sadness and disapproval upon any coarseness and impropriety.

After Margaret had given birth to two daughters, she yearned deeply for a son, so when Howard was born, he was like a messenger sent from beyond to assure her that, yes, she was a complete woman. He looked just like a cherub, an angel baby. She breast-fed him until he could walk and talk. She rose at least seven times at night to check on the rise and fall of his breath as he lay asleep in his cot. Whenever he had a cold she would put her mouth to his tiny nostrils to draw the mucus down to clear his breathing; and in the rainy season, she warmed his clothes in her bosom before she dressed him. She did not go so far as to mark his limbs with the symbolic “no trespassing” hieroglyphics, like many mothers in the village who would draw ancient African symbols with laundry blue on the backs and bellies of their babies. This was done to warn away sucking spirits. Neither did she resort to pasting sickly-smelling asafetida around the tender, vulnerable fontanelle or “mole” as Jamaicans call it, throbbing at the top of his head, in the hope that its acrid, medicinal smell would keep away ghosts and envious spirits. David, a staunch Anglican and the son of an English father, would not have had it. He did not hold with what his father called barbaric practices. Margaret, in any case, was not going to leave her son’s care and protection to any random spirit guardians. She preferred to watch him herself. However, she did surreptitiously sweep his tiny feet with a soft broom when her husband was not looking. This was to prevent him from becoming a “baffan,” or fool.

She never allowed any strangers to hold Howard. She rarely ever took him out in public until he was about three years old, because she didn’t want people to “overlook” him, that is, to look at him too much with longing, envious eyes. She did not cut his luxuriant mass of black curls which cascaded down past his shoulders until he could speak clearly. And so, for the first few years of his life, he did indeed look like a beautiful, sexless angel. Margaret dressed him in sailor suits made from appropriate sharkskin. “You are a sailor like your grandfather,” she would say as she transformed him into a nautical cherub, and her husband would say, “I don’t want my son to take after your father.” But even as Margaret dressed the boy in sailor suits, she harboured a deep fear that he would die from drowning. She had run through all the possible harm that could befall a child living in that village, and had identified the river as the thing that posed the most danger. “There was no child born in Harvey River at that time who could not swim,” my mother would say. Everyone in the village used the river. They washed their clothes there, pounding them clean on the grey shale rocks. Everyone drew drinking water from the river, which ran clean and clear, coursing down always fresh from its secret source somewhere in the interior of the Dolphin Head Mountains. They all swam in it too. Mothers would take small babies there for the ritual bathing and sopping and stretching of their limbs; they would release the babies into the river where they would instinctively kick their arms and legs.

All the children of Harvey River could swim, all except for Howard. Margaret had decided that the child should not bathe in the river, for that was where she would lose him, although no one in the village had ever drowned in it. Only once, a man from the nearby village of Chambers Pen had been stumbling home one night, drunk on john crow batty white rum, and while weaving a rummish path home in the dark turned right instead of left and fell in the river. “All the crayfish and janga must be drunk now,” said the people of the village. David’s father, William Harvey, had joked, “That man had only a little blood in his rum stream.” William was especially proud of his joke because one of his ancestors, born in 1578 and also named William Harvey, had discovered the circulation of blood and had been physician to James I and Charles I.

For a time, David humoured Margaret’s fear of the boy drowning. But when one day he came upon her bathing Howard in a wooden washtub, he grew angry and yanked the boy – who was tall for his age – out of the tub, took him down to the river, and taught him how to swim. After that there was no stopping Howard and the river. But every time he scampered away half-naked and gleeful, Margaret would worry until he returned damp and glowing like one of the Water Babies in Charles Kingsley’s story. And those babies had all drowned.

The boy grew into the most handsome of young men. He became a sweet boy, a boonoonoonoos boy, a face man, eye-candy man, pretty-like-money, nice-like-a-pound-of-rice man. Lord, women loved him. Older women looked at him greedily, as if he were some sweet confection that they could eat slowly and then lick their fingers long afterwards. Young girls just openly offered themselves to him. “Here I am, handsome Howard, pick me, choose me.” They fought to get to sit beside him at school and in church, to have him sweep those long lashes up and down the contours of their trembling bodies, to call them by name. “Yes, it’s you Cybil, you I talking to.” “Me, you mean … Howard, me? Oh yes, oh joy!” They befriended his sisters in order to get a chance to visit the Harvey household and be near to him, to drink from the same teacups from which his lips had sipped, to peep into his room and see the bed that he slept in. He could have had any woman in the district. That is why he never married, he just had too many beautiful women to choose from. Why then did he follow a Jezebel clear to Lucea, there to meet his death?

“My Irish Rose” is what George O’Brian Wilson had said when he first saw his fourth grandchild. He also called her his Rose of Tralee and his Dark Rose, and the baby just smiled. David and Margaret agreed she just had to be called Rose because nobody had ever seen a more beautiful baby. Unlike Queen Victoria Cleodine, the unsmiling Miss Jo, and the almost-too-handsome Howard, Rose was perfectly beautiful inside and out. This baby was born smiling, causing her mother to wonder why, why was this baby smiling already, what was she smiling about? Perhaps she was smiling because everybody who ever laid eyes on her, loved her.

People liked being near the beautiful baby who hardly ever cried and who cooed like a little Barbary dove at the sight of sunbeams streaming in through the front window. More than ever the people of Harvey River began to find excuses to visit David and Margaret’s house, because somehow being in the presence of this child just made everyone feel better. First of all, no one could help noticing that even more than other babies she had an especially sweet body scent, as if she had been birthed in the bed of lilies that grew behind the Harvey house. Her flawless brown skin had a pinkish glow to it, and her soft black hair curled on her head like petals. She was born with an unusually sweet disposition, which could be credited to the fact that Margaret was never happier in her life than in the years after Howard was born.

Margaret had not entertained any strange no-hard-chewing, no staid no-smiling superstition when she carried Rose. The moment she had conceived Howard, she somehow knew that she was going to get her wish for a son. And she had made herself six blue dresses which she wore throughout the duration of her pregnancy. That was the only “strange” thing that she did. After the birth of Howard, she treated the rest of her pregnancies normally, as she went on to deliver up a new baby every two years.

“Three rinse waters, they must go through three separate rinse waters so they will be completely clean.” Margaret, who was pregnant with Edmund at the time, had suspected that the girl who came to do the washing was only rinsing the family’s white clothes twice, for they were looking a little dingy. So after she had walked the girl back to the river to perform the third rinsing, Margaret returned to the house, where she had left Rose napping on a blanket on the floor, to find the child missing. They searched under every bed, every chair, table, and ward-robe, under every bush in the yard, but there was no sign of Rose, and a great wailing came up from the Harvey house.

Just at that exact moment, David’s half-brother, called Tata Edward, was taking his daily constitutional in the midday sun, when he spotted the village crazy woman walking swiftly away from Harvey River with a small child held tightly in her arms. “My little girl, my little girl, look how she favour me, look how she favour me, I am taking her with me to Panama” was what she kept saying as Tata Edward dealt her a swift blow with his walking stick, causing her to let go of his beautiful niece. Being an excellent cricketer, he then swiftly flung himself sideways onto the grass and caught Rose before she fell to the ground. The poor woman, whom the villagers called Colun, had gone insane waiting for her lover to send for her to join him in Panama. Like everyone else, she had fallen in love with Rose, and for two years she had been peeping at the child through the hibiscus hedges surrounding the Harvey house. When she had made up her mind to steal Rose, she had spent days making a house of leaves and branches for the two of them to live in in the bushes outside Harvey River. The child just kept smiling while all the commotion was going on around her.

“Look how this damn blasted woman, who fool enough so make man mad her, come take way my child! Is me tell her to fret herself till her head start run over that idiot who fool her and gone a Panama? Why she come pitch pon my house and my child?” Margaret cried and cursed the poor woman and thanked God and Tata Edward. David prayed aloud from Psalm 91. “He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High, shall abide in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord He is my refuge and fortress: my God in him will I trust. Surely he shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, and from the noisesome pestilence. He shall cover thee with his feathers, and under his wings shall thou trust; his truth shall be thy shield and buckler, thou shall not be afraid of the terror by night; nor of the arrow that flieth by day.” And the district constable came and arrested the poor woman for the “crime” of being insane while the two-year-old Rose – who, for her part, seemed to have been born with some sweet secret – just kept smiling all the time.

As she grew, Rose’s ability to keep a secret endeared her to her siblings and, later, to her school friends. If someone said, “Rose, I going tell you something and you mustn’t tell anybody you hear?” the pretty little girl would just smile, shake her head, and use her thumb and forefinger to screw her lips shut. And her sibling or school friend might say, “swear to God.” And Rose would just say, “not telling.” And you could be sure that no matter what, Rose would never, ever reveal a secret or disclose anything told to her in confidence.

Because her belly had been more pointed than round, Margaret was happy to hear that everyone predicted her fifth baby would be a boy. There were only three things that caused her any discomfort during her pregnancy. First, she felt irritable all the time as opposed to just some of the time, and she found it disconcerting that she had suddenly lost her appetite for dry white Lucea yam, which was her favourite food. But the strangest thing of all was that she, who did not believe in ever going too far from her house, inexplicably developed a case of wanderlust and began to visit friends and neighbours in surrounding villages. Everyone in Harvey River began to remark on this. “Guess who mi buck up walking out a while ago? No, Mrs. Harvey! I never see her outta road yet, and make matters worse she big, big, soon have baby!” “David,” Margaret would say, “I feel to go and visit my mother.” “You sure, Meg? You are a lady that hardly ever leave your house. I can send to call your mother, she will ride come.” “No, I want to go.”

And so it went, all during her pregnancy stay-at-home Margaret became walkbout-Margaret, until the minute that Edmund was born, when she lost all interest in ever leaving the house. The baby Edmund was born in the middle of the night. “This baby born quick quick,” said the midwife. “Him just slip out and slide right past me, like him want go walkbout already.” Because he weighed just under six pounds, they had to pin him by his chemise to a pillow so Margaret could hold him to feed him properly. “Aye, he looks like a leprechaun, like one of the little people,” said George O’Brian Wilson when he came to see his latest grandson. “Mind he doesn’t get up in the night and make mischief on ye all.” David and Margaret had had a good laugh when George Wilson said that. The little baby Edmund, who was also born with a short temper, howled.

It seems that all Edmund ever wanted to do was to leave Harvey River. As soon as he could talk, he would say, “Too dark.” Then he would say, “Too damn dark.” “What is too dark?” they would ask him, and he would say, “Here.”

As he grew he also developed a dislike for bush. “Too much bush,” he’d say, and everyone would say, “So what you expect, you live in the country.” That did not stop Edmund from disliking his birthplace. All that bush. Everywhere he looked all he could see was bush, and under every bush the duppy of some godforsaken slave. The boy’s heart did not sing out with joy as he beheld dawn rising pink and slow, moving like the folds of a woman’s nightdress up over the Dolphin Head Mountains. His spirit did not rise and canter like a young horse over the verdant green pastures each day, because he hated all the macca, the thorns set there in the green grass to pierce his bare feet. The wicked cow-itch weed that itched you till your skin would bleed. The nasty white chiggoes that bored into your feet and laid sickening mock-pearl parasite eggs. Grass lice, ticks, cow, goat, and horse shit, flies and mosquitoes.

“Jamaica is a blessed country, there are no fierce animals or poisonous snakes here, and Harvey River is like the Garden of Eden.” David was always saying that. Edmund used to kiss his teeth when he heard it. Yes, but what about all those blasted insects, what about the thick darkness? He particularly hated the peenie wallies, fireflies, damn stupid little flies with that weak on and off light coming out of their backsides. He craved real lights. Street lights. He had heard that in Montego Bay and Kingston the streets were lit by tall gas lights. “Moon pan stick” country people called those lights.

And then there was the darkness of the people. Country people, always telling each other “mawning Miss this or Mas that.” Who the hell wanted any mawning from them, thought Edmund. And the worst part was, if he did not answer them they would run and report him to his parents, who would chastise him for not having good manners. Good manners be damned. When he was thirteen years old he had actually asked his father one day where good manners ever got any black man and had his father ever noticed that backra and backra pickney, who were famous for not having good manners, always seemed to reach very far. David had been appalled by that statement, and called Edmund a savage.

Edmund could not understand how he was so unlucky as to have been born in the country. From the first time that his father took him to Kingston when he was ten years old, he knew that the city was the place for him. There the streets had names, King Street and East and West Queen Street and Port Royal Street and Rum Lane. Not “outta road,” like in the country.

Town had milk shops where he could go and order as much liver and light (light being what Jamaicans called the lungs of the cow or goat) for breakfast as he wanted. Eat, belch, pay his money, and walk out like a big man. Also rum bars where a man could order his rum by the QQ (a quarter quart), by the flask or the tot, put a question to the barmaid, who was probably called Fattie, and take her home to his room that he had rented. His room where he could turn his own key and come in at any hour of the day or night he pleased because he was his own man. Town, where cars drive up and down day and night. Cars and buses and trucks and tramcars ran all the time. Not like this back-a-bush place with only donkey, mule, and horse. Who the hell said country nice? Not Edmund.

He considered it God’s make mistake why he was born in Harvey River. He was Moses among the bulrushes. If only Pharaoh’s daughter would just appear and carry him to town. As a child he would run outside to stare at any motor vehicle that managed to fight its way up to the village. He fashioned a steering wheel from an old pot cover and “drove” wherever he went, going “brrrum, brrruum” in imitation of the noise of motor vehicle engines, and he made hissing, screeching sounds whenever he stopped, like the boiling over hissing brakes of trucks.

David rode a horse and Margaret had a pretty, dainty-stepping donkey, but nobody who lived in the village owned a motor car. Edmund had been taken to Montego Bay as a child and had seen the taxi men driving tourists around. Even as a boy, he had been struck by the elite corps of smartly dressed men in starched white shirts and black pants, who all spoke “Yankee” and smoked cigarettes and had the prettiest women, because girls just loved a man who drove a car. Later, he would hear that tourist women – mostly rich Americans and English women – would sometimes fall in love with a taxi man.