Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

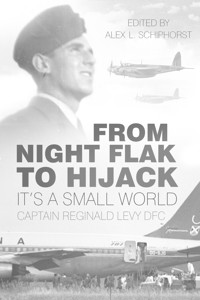

This is the autobiography of Reginald Levy, a British pilot who reached a total of 25,090 flying hours in over forty years of civil, military and commercial aviation. He recounts his training and military operations as an RAF Bomber Command pilot during the Second World War. Enthralled and immersed within the ever growing world of aviation, he flies sixty-four types of aircraft between 1941 and 1981 and takes part in the Berlin Airlift. He joins the Belgian airline Sabena in 1952. In 1972, he is hijacked by Black September terrorists and plays a heroic part in the liberation of the hostages thanks to his professionalism and training. Not only does the book offer an insight into the hardships and camaraderie of the Second World War and of the Cold War, it also gives a first-hand account of a Palestinian terrorist attempt. Two of the Israeli commandos who freed the hostages would go on to become prime ministers of Israel – Barak and Netanyahu. The epilogue is provided by his youngest grandson, Alex.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to the people who helped me edit, read, write and who offered me endless support and comments regarding my grandfather’s autobiography and the epilogue to his unfinished story.

I wish to thank above all my mother, Feeka, without whom this book would never have been finished and published. She was truly the backbone to getting the book done and provided me with endless remarks and comments and assisted in the editing and proofreading. My thank you here will never be enough to give her the proper homage she deserves.

A great thank you also goes to my whole family, my auntie Linda and my uncle Peter, who assisted me with information, lent me material, and helped deal with administrative matters.

My most sincere thanks also go out to ex-Sabena crew members for their valuable help in contacting and identifying fellow staff, planes, routes and places, as well as for their many anecdotes which enabled me to complete the Epilogue.

I wish to express my gratitude to the many people who accepted to have their names or names of loved ones mentioned in the book, for their enthusiasm, best wishes and further encouragement for the publication of Reg’s memoirs.

Lastly, I would like to thank Shaun Barrington, our publisher, for his enthusiasm and for believing in the book. His words ‘read enough, I want to publish’ will forever remain engraved in my memory.

Alex L. Schiphorst, 2015

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Preface: My Story

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Epilogue

Types of aircraft & Acronyms

Plates

Copyright

PREFACE

MY STORY

This narrative was started in New York, in September 1982, when I was there on a shopping trip after I had retired. It is an attempt to leave, primarily for my grandchildren, a record of times that have thankfully in many ways changed out of all recognition.

I have not stressed the hardship and privation that we endured, particularly during the war years, nor have I been able to pay sufficient tribute to the courage and support of my wife, Dora.

I hope that none of you who read this will ever have to go through the trials and tribulations of raising small children in one small room, sharing a kitchen and bathroom with the landlady and her family, often with only an outside toilet, no heating, very short of money and at one’s wits’ end trying to scrape a meal for nothing.

I had a very glamorous life, but it was not so glamorous at the beginning and no words that I can put here will ever tell you how much I owe to Dora.

Time plays funny tricks with memory. If I were asked what regrets I have I would reply, ‘Oh if only I had kept a diary.’ That is the only advice I give to you. Put it down on paper and take care of it.

CHAPTER ONE

I was born in Portsmouth on 8 May 1922. At a very early age, certainly before I was two, we moved to Liverpool where we lived for a while in the house of my father’s mother.

My father, Cyril, who was Jewish, had met my mother in Edinburgh, while she was visiting her elder brothers. My father was in Edinburgh on business for his father. My mother was sixteen and certainly not Jewish but it was love at first sight and they were married in Edinburgh after she had converted to Judaism.

I was born when she was seventeen. My father was twenty-one when he married and I was the same age when I married and so was my eldest son, Peter.

The house in Liverpool was a lovely Edwardian one in the then fashionable quarter of Bedford Street, just off Abercrombie Square, to which we had our own key to enjoy the beautiful gardens in privacy. The house, No 76, was a child’s paradise having dozens of rooms in which to play ‘Hide and Seek’. There was a real ‘Upstairs, Downstairs’ with a huge kitchen, scullery, larder, and servants’ quarters. Upstairs were a big billiard room, cloakrooms, parlour, dining room, and lounge.

My paternal grandfather, Louis, was a successful businessman although he once turned down the offer of financing another Liverpool man who came to him with the idea of opening one or two tea shops. ‘It will never catch on,’ said my grandfather, so Joe Lyons went on to do very well with someone else!

Living with us at Bedford Street was the second youngest of my father’s family, my Auntie Muriel, who was a pioneer of radio. She was already famous as ‘Auntie Muriel’ of the Children’s Hour broadcast every day at 5.15 p.m. She was a prolific writer of children’s stories and had her own page in the Liverpool Echo. She was a scriptwriter for the Toytown series and played the part of Larry the Lamb in many of the Toytown episodes and partnered Doris Hare (‘Aunty Doris’) in radio skits.

Also living with us at Bedford Street was the youngest brother, my Uncle Stuart who eventually became a very successful film producer and partnered Nat Cohen in Anglo-Amalgamated Films Ltd, which became famous for the Carry On series.

My father was given the job of managing the ‘Scala’ cinema on Argyle Street in nearby Birkenhead. His Uncle Alf was a Liverpool councillor and owned the cinema together with the Liverpool ‘Scala’ and ‘Futurist’ on Lime Street, Liverpool.

We were, by now, living in another big house at 42 Hamilton Square, Birkenhead, which my mother promptly opened as a café/restaurant called Nan’s Café. Even living in Birkenhead, I attended my father’s old school, the Liverpool Institute, later to become the school of Paul McCartney amongst other famous old boys.

There was a Preparatory section of the Liverpool Institute in which I was enrolled and I used to take the ferry to Liverpool. This was an economy measure as the fare was only a penny as opposed to threepence on the much faster Underground. I was given the fare for the tram from the Pier Head to school but would very often walk, if I was early enough, and pocket the money with a gentleman’s agreement from my parents. The Mersey Tunnel was not to open for another three years and I was to benefit from a school holiday to watch King George V and Queen Mary open it in 1934. Not that it would have helped me had it been open as it was only for cars.

Around this time, my father was offered the ‘Plaza’ Cinema, in Manchester Square, Blackpool. So we moved to a semi-detached house at 29 Horncliffe Road, South Shore and I started at the Blackpool Grammar School. These were happy days. I had a brand new bicycle, a Royal Enfield costing £3.19s on which I used to cycle the not inconsiderable distance to school every day, even coming home for lunch.

I, like most boys, was fascinated with aeroplanes. Even in 1935 people would run out of the house if one were heard overhead. I remember seeing the Graf Zeppelin flying over Blackpool Tower on its way to Barrow-in-Furness where the Naval Yards were only too visible from the skies.

My heroes were Sir Alan Cobham and Captain Barnard whose flying circuses toured Britain. I was a horrified witness to the disaster when the passenger-carrying formation flight from Captain Barnard’s Circus collided over Central Station and plunged into the town. There were few survivors and yet, thirty or more years later at a dinner party at our house in Brussels, I would recall the event only to hear the amazed comment from one of my greatest friends, Gordon Burch, an Air Traffic Controller with Eurocontrol, that his father had given him the 7/6d fare to be a passenger on the flight and that he had seen the whole incident and had been in the one aircraft that had managed to land safely.

My own experience with aeroplanes began when I was given a Warneford stick model aeroplane which actually flew. My father and I took it down on the sands, wound up the elastic then hand launched it. It soared up to about 20ft, turned and flew, beautifully, out to sea, never to be seen again. Then came the splendid Frog models; an ingenious and well-made monoplane which came in a winder box with instructions to lubricate the elastic with banana oil which could be purchased at an expensive shilling extra. How lovingly that was applied and how well the Frog flew.

Aeroplanes were always well-featured in the so-called Penny Dreadful comics that actually cost twopence. At least one came out every day and there were always free gifts including catapult-launched gliders which actually flew very well and could be made to ‘loop the loop’.

As I remember, there was the Adventure on Monday, the Wizard on Tuesday, the Gem on Wednesday, the Rover and the Champion on Thursday. Saturday brought my favourite, the Magnet and also, years ahead of its time, Modern Boy. The Hotspur with all its different types of school stories came later but soon caught up with its many rivals. Even then there was ‘flak’ from people who said that the stories were too lurid and encouraged violence. There was no television to blame in those days. Also, reading too much would ‘strain’ your eyes but despite this I was and am blessed with wonderful eyesight and am still an avid reader. I am grateful to the wonderful free library service which I used all the time as a boy and I must have read every Percy F. Westerman novel ever published.

I left school at fifteen years of age. English, particularly elocution, and French were the only subjects I was any good at. Maths were terrible and I loathed them, and Science. I hated school, mainly because of the rampant anti-Semitism that reigned in that era, particularly in Liverpool. I was small for my age and was bullied, particularly in Liverpool.

I went on to find a variety of jobs including a grocery assistant at ‘Blowers’ at Abingdon Street Market, darkroom assistant at ‘Valette Studios’ in Bank Hey Street, and general factotum at a photographic developers, Hepworth’s D&P Studios in Catherine Street. On my first day, I walked into a very dark room so switched the lights on. About sixty puzzled customers were later told that their films ‘hadn’t come out’. Despite the inauspicious start I enjoyed working there and learned the whole procedure of developing, printing, enlarging etc. which I have never forgotten.

I had always had a good singing voice and was one of the ‘Sisters and the Cousins and the Aunts’ in H.M.S. Pinafore, complete with crinoline and bonnet, at the Liverpool Institute, which boasted a full-size stage and auditorium in the school hall. One day, when about 14 and before my voice had broken, I entered for Opportunity Knocks, then called simply, Hughie Green and his Gang and run by the child prodigy who was then about seventeen. He was starring at Blackpool’s famous old music hall, Feldman’s Theatre. I sang ‘Marta, Rambling Rose of the Wildwood’, the signature tune of Arthur Tracy, the ‘Street Singer’, a famous radio and music hall star of that time. To my amazement I won my heat and had to come back for the Final on the Saturday night. The judging was by audience applause and I was thrilled to hear the noise that acclaimed my effort. I won the first prize of £5 which bought me a new bike and I was convinced that my future was on the stage. The strange thing was that Hughie Green also went on to become a pilot during the war that was so close. He was a ferry pilot bringing much needed aircraft from the US to Britain. I never met him again but would have loved to have done so to recall those days.

I was a very keen supporter of Blackpool Football Club, and loved playing in goal, but was at Blackpool Grammar, which was a rugby school and I loathed rugby. A typical Saturday then would be to play football for my local club, ‘Streamline Taxis’, at Stanley Park in the morning, then stand in the Boys’ enclosure at Bloomfield Road to cheer on Blackpool. In the evening I would either be at the newly opened ‘Marina Ice Drome’ at the Pleasure Beach or be playing table-tennis for my club ‘Blackpool Jewish’. I was quite good at this and was selected by the Lancashire Association to be trained for a season by the visiting World Champion, Victor Barna. He would put a sixpence on his side of the table and it was yours if you could hit it with a half volley return from one of his famous ‘Barna flicks’, a devastating backhand smash. With all this physical exercise I was always being told, ‘you will overstrain yourself’ but I wish I was as fit today as I was then.

Blackpool FC was managed by the great old Bolton and England inside-forward, Joe Smith. Clubs kept their managers for years then and Joe managed Blackpool from before the war until he was past seventy. I had the pleasure of flying him and the team back to Manchester in the Fifties when I had joined Sabena. I introduced three of our children to him and the team, including the famous Stanley Matthews.

It was my pleasure and privilege, many years later, to meet up with Stanley Matthews, by then Sir Stanley, in South Africa where he went every year to coach underprivileged black footballers, and we became good friends. By coincidence, he was a Corporal in my father’s office when my father had been stationed as an RAF Signals Officer in Blackpool during the war. My wife Dora and I went to a great dinner in honour of Stan in Johannesburg and it was wonderful to meet up with Scottish international centre-forward, little Jackie Mudie and the South African English international left-winger, Bill Perry, who scored the winning goal (from Matthew’s copybook pass, of course) in the famous ‘Matthews Final’ of 1953. We also met Stan Mortensen several times during the war, as he was also in the RAF and was always good to me in providing excellent seats wherever they were playing.

Around 1936 the ‘Plaza’ was sold and my parents went into the boarding house business, buying or more probably renting 164 N. Promenade, which they named the ‘Avalon’. It had about twelve bedrooms and was in a good position opposite the Hotel Metropole. As it was also next to a sweetshop and the ‘Princess’ Cinema, I was in my element, particularly as we had free tickets to the cinema due to Dad’s association with the trade and the fact that we used to put up a poster in the hall showing what was on next door. It was a very good cinema and showed ‘first run’ films and I can remember the hullabaloo that went on when Gone with the Wind was shown there just before war broke out.

In the summer holidays I would get various jobs along the ‘Golden Mile’, though it wasn’t called that then. It was just ‘Luna Park’ or Central Promenade. A lucrative job was acting as a ‘stooge’ for the operator of the fruit machines that were scattered along there. The fruit machines were arranged in a circle with the man in charge on a stand in the centre and when business was slack he would catch my eye and I would play the machines and he would ensure that I kept on winning until a crowd gathered around and I would walk away.

Among the many attractions all along the Central Promenade, the Rector of Stiffkey, in his barrel, and Dr Walford Brodie with his genuine American Electric Chair were popular, while Pablo’s was the ice cream parlour and deservedly so. At the end of the season – and the day was never publicised – he would give away all his remaining stock. Somehow the word would spread around through a magic grapevine and schoolchildren from all over Blackpool could be seen running and cycling to the little back street behind the Winter Gardens where Joe Pablo would be sitting on the running board of his Rolls-Royce reading the Daily Worker.

About this time, Gracie Fields was making Sing As We Go in Blackpool and I was one of the lucky extras paid £2 per day to run behind a lorry, supposedly carrying Gracie waving back to us. In fact there was only a camera on board with the Director, Basil Dean, shouting, ‘Come on, you buggers, wave, earn your bloody money.’ I met Gracie when she was appearing at the Grand Theatre. I asked her, politely, for her autograph. ‘Here you are, luv,’ she said, and gave me sixpence for ‘talking so lovely’.

CHAPTER TWO

When Neville Chamberlain made the sombre announcement on Sunday, 3 September 1939, that ‘this country is now at war with Germany’, I was seventeen and four months.

I had been working for some time as the office boy to a well-known firm of chartered accountants, Ivan G. Aspinall. God knows how I survived as my maths were still non-existent. Ivan G. was a distinguished looking gentleman, the double of Walter Connolly, an American film star of that time. Ivan was also a Director of Waller and Hartley’s, the toffee makers, and it was always a pleasure to take documents up to the factory, behind Devonshire Square, where the factory girls would make a great fuss of me and load me with Milady toffees despite the rationing.

Conscription was now in full swing. The ‘call up’ age was twenty and you could be put into any of the Services, later even sent down the mines as a ‘Bevin Boy’. You could, however, volunteer for flying duties in the RAF from the age of eighteen. This I did, causing such a row between my father and mother that he promptly followed suit and volunteered for the RAF even though he was over age. He was accepted, commissioned and became a Signals Officer for some time at Blackpool and later in the Middle East in Palestine and Egypt. He was present at the famous Yalta Conference between Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin.

I made my first ever visit to London to be interviewed by a Group Captain for flying duties. He tried to persuade me to become a Navigator (the RAF was already looking ahead even in 1940) but I was completely set on becoming a pilot and would have nothing else. In the end he gave in but warned me that I would have to wait a long time before I was actually called up. In the event I was called up four weeks later, enlisted as AC2 R. Levy 1380172 and sent to Cardington in Bedfordshire for my ‘jabs’ and kitting out. I was then sent to Bicester in Oxfordshire as an AC2 awaiting training and given ‘ground duties’, which were mainly latrine cleaning. There were about six of us and we arrived late at night but it was like daylight outside as it was the night that the Germans bombed Coventry.

Bicester was a bomber station of Bristol Blenheims and I became friendly with one of the pilots, also from Blackpool, Sergeant Hoggard. He told me that he was flying up to Squires Gate, the Blackpool RAF station, and would take me with him if I wanted. Did I! I was so naïve I didn’t even get permission but just got into the cockpit of the old Avro 504 biplane and off we went. This was my first flight ever, some time around November 1940 and it was wonderful. I just had time for a quick tram ride to the Avalon to find it full of airmen as it had been ‘commandeered’ by the RAF. My mother was far from pleased with this and complained bitterly to the authorities that it was not ‘proper’ that she and my sister should be alone in a big house with so many ‘licentious’ airmen. The authorities agreed with her, removed the airmen and filled the Avalon with some thirty WAAFs as the Womens’ Royal Air Force was then known. I wasn’t grumbling but my mother was livid, as the airmen used to do all the heavy odd jobs and repairs around the place. The WAAFs though stayed until the end of the war.

I arrived back at Bicester only to find myself on a charge or ‘fizzer’ as it was known. ‘Absent without leave’ was the accusation but an understanding Flight Lieutenant dismissed it, then gave me six days ‘jankers’, which consisted of cleaning out the Sergeants’ Mess latrines. I took great pleasure in using those latrines two years later when I visited Bicester as a fully fledged Sergeant Pilot.

Towards the end of December 1940 I found myself posted to Stratford-upon-Avon, which was a receiving centre for would-be pilots. I was billeted at the Shakespeare Hotel, which was very comfortable albeit I shared a double room with eleven others. After a couple of weeks of marching up and down Stratford and passing Anne Hathaway’s cottage ten times a day I was posted to start my training proper at No 6 ITW (Initial Training Wing) Aberystwyth. This time I was billeted in the Marine Hotel, right on the freezing promenade. At Aberystwyth we had extensive courses in maths – still my bête noire – navigation, Morse and Aldis signalling, rifle and clay pigeon shooting, meteorology, aircraft recognition and of course hours and hours of ‘square bashing’. We would have a big breakfast at six then meet on the promenade for half an hour of PT followed by a run up and down ‘Constitution Hill’, the huge mountain, or so it seemed, that lay at the end of the promenade.

We were also given extensive medical and dental check-ups. I remember the aged Welsh dentist (at least forty!) saying to me, ‘I am too old to fly but I will make sure that you have your own teeth all of your life.’

At the end of six weeks and well into a freezing February we were ‘passed out’ as LAC (Leading Aircraftsman) u/t (under training) and were paid the princely sum of 6s 6d per day. It really was a lot of money as all our food and accommodation was paid for.

Because of the very severe winter of 1941, the British Flying Schools had ground to a halt so there was nowhere for us to go. We would breakfast at seven, report for PT and roll call at nine and then be dismissed for the day. The majority of us were aged between eighteen and nineteen so were already hungry again. We would go to one of the several cafés where a breakfast of two poached eggs on toast, chips, bacon and sausage could be had for tenpence. Rationing seemed to have bypassed North Wales although it must have come later. Our ample leisure time was well catered for as the London University for Women had been evacuated to Aberystwyth. We were given leave and leave again and I spent more time in the Blackpool Tower Ballroom than on the parade ground.

Eventually, towards the end of March we were taken to a school hall in Aberystwyth and told that we were no longer to consider ourselves as being part of the RAF. It was explained to us (us being ‘B’ Flight) that we were being sent to an unnamed country that was ‘neutral’ and were being trained there, and that they, the neutral country, could not accept belligerents in uniform. Accordingly we were given £20 clothing allowance to buy ‘civvies’ suitable for a hot climate and sent off on a short overseas leave. We were issued railway warrants and told to report to Wilmslow, near Manchester, in a week’s time. At Wilmslow we were issued with the heaviest grey flannel double-breasted jacket and trousers that had ever been made. To cap these bizarre items we were issued with old-fashioned pith helmet ‘topees’ complete with ear pockets for inserting radio ear pieces whilst flying. They had obviously lain in some storehouse since the 1920s when they would have been issued to the intrepid pilots of such aircraft as Wapitis, and Harts for use in the Middle East. With these in our kitbags, which must have weighed 55lb, we struggled along the road to the railway station where a train was waiting to take us on the long journey up to Greenock, near Glasgow.

Arriving there, one cold morning in May 1941, we found a large ship waiting at the dockside. Due to the wartime restrictions there was no name on the bow but, on boarding, we found out that she was the White Star liner, Britannic.

As an eight-year-old I had gone down to the Pier Head in Liverpool to watch the Britannic set out on her maiden voyage. I little knew then that eleven years later I, with 400 other cadets and a complement of 2,400 Air Force, Army and Navy personnel, would be standing on her decks waiting to start the biggest adventure of my life up to then.

We left Greenock escorted by the famous battleship Rodney and four destroyers. The size of the escort for one troopship was astonishing but the cargo was precious. On board was all that was necessary for setting up the pilot training scheme in the United States, to be called the Arnold Scheme, after its founder, General ‘Hap’ Arnold. This plan, of which we were the forerunners, was to train some 6,000 pilots for the RAF.

We were only two days out into the Atlantic when the Rodney and three of the destroyers left us. We cadets were pretty good at Aldis and as one destroyer left he signalled, ‘Bismarck out. Knows your course and speed. Make full speed. Good luck.’

Full speed on the Britannic was about 28 knots and the Atlantic was quite rough. There were many of us, especially those in the crowded quarters of the bow and stern, who would not have minded too much if the Bismarck had caught up with us.

Then we heard of the dreadful loss of the Hood with only a handful of survivors and the news that our escort, Rodney, had finished off the Bismarck after she had been crippled by the gallant attacks from the old ‘Stringbags’ as the Fairey Swordfish torpedo-carrying biplanes were called.

We docked at Halifax, Nova Scotia, towards the end of May 1941. We were marched straight on to a waiting train, and we stayed on that train for nearly two days and nights before being disembarked on to a platform that stated this was the Manning Pool of Toronto. A huge figure of a man with the rank of Flight Sergeant in the RCAF stood before us. ‘Get fell in, you horrible lot!’ he screamed. We formed into a sweating, humid, weary, grey-flannelled blob. We were told to ‘forward march’ and were marched in to a large hall where tables were groaning with all the foods that we had forgotten existed. Steaks, chops, eggs, ham, bacon, butter; everything was there. The RSM’s face broke into a thousand lines, wrinkles and cracks, which was the nearest he could get to a smile. From then on we were given the freedom of Toronto. We had now been issued RAF uniforms again to wear until we went on to the USA. We were the first RAF to be seen there and the sight of our uniform was sufficient to open up the doors of cinemas, restaurants and pubs. It was physically impossible to pay for anything. One day a friend and I decided to hitchhike to Niagara Falls. A car pulled up; the driver, a middle-aged man, asked us where we wanted to go and, on learning, told us to get in. He returned home where his wife and two very pretty daughters made up a picnic and we all drove over a hundred miles to see the Falls.

Another wonderful evening was when we were all invited to a dance where the great Louis Armstrong was playing. No one danced but we all stood in front of the orchestra and applauded; just like in the movies! It all had to end of course and after two wonderful weeks in Toronto we entrained for the long journey to our destination, Albany, Georgia.

CHAPTER THREE

Albany was a very small southern town and in 1942, still, at heart, part of the Confederacy that had seceded from the Union. The first thing that we learned was that ‘damyankee’ was just one word and not two. The accent, especially that of the girls, completely charmed us. The phone in the lounge mess would ring and we would very often hear, ‘Are y’all a British boooy? Would y’all just tolk?’ They were completely disbelieving when we told them that it was they who had the accent.

We learned how to fly and we learned the hard way. General Arnold had made it quite clear that we would follow the very tough itinerary prescribed for the US Army Air Corps, and that standards would not be relaxed despite the crying need for pilots in the UK. We got the full peacetime training, and very much later in my career, I said, over and over again, that I am alive because of that training and I am eternally grateful for it.

Of the 500 or so cadets who started training at the Southeast Training Center as it was known, only 120 of the class of 42A (the first class to graduate in 1942) were awarded the coveted silver wings. Many of those who were ‘washed out’ were sent to Canada to continue their training and were flying operationally in England long before we returned.

The school, run by civilian Instructors, but with army officers as Check Pilots and responsible for discipline, was based on the West Point system of Upperclassmen and the ‘honour system’.

We, as the first class of British ‘caydets’ had an American class (41F) over us to administer discipline and the ‘hazing’ that was the way of life. There were many rigmaroles and set phrases to learn. At meals an Upperclassman would tell an unfortunate Lowerclassman. ‘Take a square meal, Mister’ and the poor underdog would have to bring his food to his mouth and insert it at right angles throughout the meal whilst sitting on the obligatory front 6in of the chair, which was all that we were allowed throughout our Lowerclassmen days.

Room inspection, always carried out by the Upperclass, involved the running of white silk gloves over cupboards, beds and floor. One speck of dust and a ‘gig’ was the result. A nickel (5 cents) would be thrown on your stretched-out blanket and it had to ripple. The sheet had to have just 6½in showing and this was measured carefully. So many ‘gigs’ and our only free time off camp from Saturday noon until Sunday 6 p.m. was curtailed by hours of marching in full dress uniform, sword and pack in a blazing Georgia sun and 100 per cent humidity.

There were several ‘re-mustered other trades’. Hard bitten corporals and sergeants who found the hazing very hard to take. To be told to, ‘Take a brace, Mister’ by some green college boy and made to stand with your chin and stomach tucked in was more than some of these veterans of the bombing of airfields such as Biggin Hill could take. ‘Get stuffed’ and ‘Belt up’ were some of the milder replies but they didn’t see much of Albany during our six weeks of being the Lowerclass. The ‘Special Relationship’ wore a bit thin at times. There was a patriotic song at that time which began ‘Off we go, into the wild blue yonder’ and finished ‘nothing will stop the Army Air Corps’, to which the RAF lads would add ‘except the weather’, with the ensuing often bloody result.

The Commanding Officer was a West Pointer with absolutely no sense of humour. We nicknamed him the ‘Boy Scout’ because of the wide brimmed hat he wore. He never understood the British and despaired of us ever winning the war.

The compensation for the really tough going was the hospitality we received during our precious few free hours, from the citizens of Albany who took us, sometimes quite literally, to the bosom of the Deep South. We all tasted the fabulous Southern hospitality. I still have the memory of lush, warm evenings with the croaking of bullfrogs, the incessant noise of the crickets, the scent of magnolia blossom and the creaking of rocking chairs on Southern porches to remind me of the adolescence I spent there.

CHAPTER FOUR

Our day began at 5 a.m. with calisthenics, then the room had to be cleaned and left spotless. We were billeted two to a room with our own shower. Fabulous luxury compared to our RAF billets. The school had its own resident dietician, a new word to us. ‘Miz’ Tickner saw that we had the most fabulous meals I can ever remember eating in my entire life. We were bronzed from the sun, supremely fit and ready for anything.

Flying training always took place in the early morning before the relentless sun could bake the landing surface so hard that you would float for miles when trying to land, cushioned by the warm air rising off the ground.

The aircraft that we first flew in was the Stearman PT-17, made by Boeing and a wonderfully aerobatic aeroplane. It was a sturdy biplane but we were not allowed the luxury of any instruments as we were being taught to fly ‘by the seat of your pants’. No airspeed indicator or altimeter. You quickly learned to judge your speed by the different sound of the airstream whistling through the struts and wires that held the wings together and estimated your height from the dwindling trees and figures beneath you.

My first Instructor was a very small man, the size of a jockey who had come to Darr Aero Tech, as the school was called, straight from Hollywood where he had been a stunt pilot featuring in such films as Hell’s Angels and The Dawn Patrol. He was called Gunn and rejoiced in the nickname ‘Kinky’. Although we had all passed our ground training at ITWs, mainly in seaside towns such as Torquay, Babbacombe, Newquay and Aberystwyth, few, if any of us had ever been near an aeroplane, let alone flown one. Kinky Gunn’s initiation for his bunch of three pupils was to take us up – one by one – and throw that Stearman all over the sky until we couldn’t tell the horizon from the sky or the ground. If you survived that without losing the fantastic breakfast you had just had then the battle of teaching you had begun. It started with some basic rules. ‘There are old pilots and there are bold pilots,’ he would say, ‘but there are no old, bold pilots.’ To the end of my long career I could never line up on a runway, after being cleared for take-off by Air Traffic Control, without a long hard look at the approach to check whether there was an aeroplane coming in to land. Pretty basic you might think but we had no radio at Darr, just a man who gave you a green light or a red and was human and so, fallible.

One of Kinky’s favourite tricks was to ‘buzz’ the (out of bounds!) red light district of Albany on one of the very early training sessions. ‘That’ll shake them out of their beds,’ he would yell over the slipstream as the wheels of our plane would scrape the roof. He must have been a good teacher, though, because we three were the very first pupils to solo after some seven hours of ‘dual’.

I had made what I thought was rather a bumpy landing when the figure in the cockpit in front of me disappeared and there was Kinky, standing on the wing beside me. ‘OK Reg,’ he said, giving it the hard ‘G’ that was the American pronunciation of my name. ‘Take her up and give me a nice landing,’ and he was gone. I suspect that his heart was beating as loudly as mine. With the now lighter aircraft, I was airborne before I knew it. It was 28 June 1941 and I was nineteeen years and forty days old.

The thrill of that first time of being alone in an aeroplane and master of it, albeit a very timid and quivering master, remains with me to this day: forty-one years and 25,097 flying hours later. The tales of our adventures and misadventures were related that week over the ubiquitous Cokes. All flying schools in the US were dry and we were only allowed out at the weekend if we hadn’t collected the dreaded ‘walks’. The tales that we recounted were part of our relaxation and we would gather in the comfortable lounge after we had completed our homework from the extremely thorough ground courses we were being given.

One of our chaps, Ted Headington, later tragically killed at Advanced Flying School, had been sent for his first solo, and his Instructor, as was the custom, was standing in the centre of the field watching his pupil. As Ted was approaching he encountered a strong thermal current which turned him upside down at about 500ft. Ted continued the ‘roll’ and made a perfect landing to find his Instructor apoplectic with rage at Ted’s disregard for safety in doing aerobatics and gave him enough ‘gigs’ to keep him at Darr for the rest of his time there.

As we became more proficient and as our confidence grew we were introduced to the thrill of aerobatics. Slow rolls, loops, lazy eights and spins (which I hated) were all taken in our stride although, even in those days, I began to feel the urge to fly big aeroplanes with lots of engines.

Like all American colleges, Darr Aero Tech encouraged their pupils to produce a class magazine. Ours was called PEE TEE (Primary Training) and a position on its editorial staff carried the privilege of being allowed into Albany, occasionally, to liaise with the printer and to find advertising from the many willing shopkeepers who loaded us with samples of their goods including a very nice record player. I had always been a very keen photographer and loved writing so I was appointed one of the editors. The magazine boasted the usual photographs of each class member with a brief biography, which make interesting reading today. I still have a copy of the original issue. The photographs were reminiscent of the Hollywood films in which my Instructor, Kinky Gunn, had figured. Cloth helmets with goggles worn on the forehead and skilfully re-touched. Not that we had many wrinkles at that age!

Our sorties into Albany always took us to the only hotel, the Gordon. It had a downstairs lounge called the Clubroom where we were introduced to a lethal drink called a Zombie … strictly only two to a customer! Mint juleps were also very much in fashion but we were not heavy drinkers and Cokes were always the drink most in demand. After all we were only a few miles from where they were invented. There was a piano and one of our bunch, Joe Payne, used to astound the American cadets with his wonderful rendering of ‘Honky Tonk Blues’.

The drugstore on the corner was another American institution that we loved and Lee’s, in Albany, was our favourite. The pretty daughter of the Lee family who owned the store was the main attraction, but she broke many hearts by marrying a popular aerodynamics Instructor, ‘CsubL’ Clark, so called for his love of the phrase CsubL in explanation of the equation of Lift. We were introduced to banana splits, the like of which I have never tasted since and in the little restaurant next door, we were served sizzling T-bone steaks that really did sizzle as they were served on an iron platter at the special price of $2 to British cadets … $2.50 to everyone else.

The nearby Radium Springs, was our favourite swimming place with its restaurant and weekly ‘Georgia Peach’ competition. It was also noted for the iciest water that I have ever encountered in the world, including Alaska.

We were, by now, Upperclassmen ourselves to the new class of 42B, also British cadets but we were not able to bring ourselves to treat them as we had been treated by the American Upperclassmen and after a few half-hearted (and derisively greeted) efforts we gave up and settled down to completing our course of Primary training and proceeding to the next stage … Basic.

CHAPTER FIVE

Basic training was later cut out altogether and replaced by a much shorter course of just two stages, Primary and Advanced. As we were still doing the full peacetime training, we were given a wonderful two weeks leave in Florida at the expense of the US Government. There we first met the wonderful USO Servicemen’s entertainment organisation. During that time I had the privilege of dancing with the beautiful Rita Hayworth; the orchestra was playing ‘Amapola’, and as I took that beautiful woman around the floor, I would not have changed places with anyone in the world. We were, however, soon Greyhound bussed to Macon, Georgia, to the Cochran Field Basic Training School, which was now under the US Army’s control. There were no civilian Instructors, but rather fierce-looking Second and First Lieutenants (pronounced lootenant) with weird and exotic names. We also renewed acquaintance with our previous tormentors of Class 41H who had preceded us there.

Basic meant the Vultee BT-13A, a huge, or so it seemed to our Stearman-oriented eyes, underpowered, fixed undercarriage monoplane. I remember it as a brute of an aeroplane, heavy on the controls and very difficult in the aerobatics, which were always such an important part of the American training. The hours began to pile up and suddenly we were ‘veterans’ with over 100 hours.

At that time, our more unfortunate colleagues in England were flying against the enemy with only thirty or forty hours. At Cochran Field we were introduced to the pleasant practice of sending two cadets up together to practise their skills without the eagle eye of the Army Air Corps Officer on you all the time, and these flights were very much appreciated.

Towards the end of our Basic course the rumours spread that our Advanced and final training would take place back at our beloved Albany. Not at Darr Aero Tech but at the large military field named, in the American tradition of calling their airfields after Air Corps personnel, Turner Field. I never did find out who Lieutenant Turner was.

So now it was Turner Field and our first encounter with a ‘real’ aeroplane. The AT6 (Advanced Trainer) was already in use all over the world. It was, and still is, better known as the Harvard and was absolutely identifiable from a distance by its characteristic ‘buzz’ or high pitched drone caused, I was told by the knowledgeable, by the effect of its propeller tips nearing the speed of sound as they rotated. The Harvard had a retractable undercarriage (one more thing for us to remember!) and even looked like a fighting warplane. Its main disadvantage was a tail wheel which was partially steerable by the rudder pedals. If one was not extremely careful on landing, the whole aeroplane would suddenly make a complete 360 degrees turn which was very disconcerting, to say the least, was violently disliked by our officer Instructors and was a certainty to earn at least an hour’s ‘walking’ at the weekend.

Georgia, from the air, was predominantly red from the characteristic colour of the red earth or clay, but there were plenty of good fields around that we used as practice grounds for forced landings. Your Instructor would suddenly cut the engine when you were at about 6,000ft and not expecting it, and woe betide you if you had to use the engine again before you put the aeroplane down in one of those fields. The fields had another use, however. It was fairly common to arrange with the current girlfriend to rendezvous at one of them and we would land and then take them for a ‘spin’ as we called it. The penalty for being caught was instant expulsion from the course, which only made the whole thing more savoury. A certain Irish corporal had made a date with his girlfriend at one of these fields but, unfortunately, got so excited about it that he forgot to put his wheels down and slid along on the belly of the aircraft in front of the startled girl who thought that he had done it to show off. His reflexes were fantastic, however. He grabbed the microphone and called up ‘Mayday, Mayday,’ the international call sign for an emergency. ‘This is Army plane 100,’ he said. ‘My engine has cut and I am going to try and force land in …’ naming the field where he was sitting. Back came the reply from Turner Tower, as our home base was called. ‘Keep a cool head, boy, and do not, repeat, do not put your wheels down.’ This was standard practice in a real emergency to avoid tipping over if you landed on rough ground or in one of the many swamps. It also kept the landing distance shorter and only bent an easily replaceable propeller. Paddy actually got a ‘green’ endorsement in his logbook for outstanding airmanship. I don’t know what his girlfriend gave him!

Another story that went into the ‘line book’ as it was called in the RAF (shooting a line was boasting of a personal feat) was when the Tower was trying to contact a plane with one of the cadets in it. ‘Army plane five zero zero, this is Turner Tower. Are you receiving me?’, was repeated several times without success. Eventually the Tower came up with ‘Army plane five zero zero, is that you over the field? If you are receiving me waggle your wings.’ Back came the reply in that clipped British accent that the Americans tried, vainly, to imitate. ‘Turner Tower, this is Army plane five zero zero, if you are receiving me waggle your Tower.’ That earned him a couple of hours ‘walking’.

Another time the Tower was called by a British voice that said, ‘Turner Tower, this is Army plane 100. I am out of petrol. What shall I do?’ There was a flurry of words then one of the Instructors was hurriedly summoned to the microphone. ‘OK Army plane 100. Don’t panic. Keep cool and calm. Put the nose in a gentle glide and look around. Try to find one of the emergency fields. What is your height and position?’ The cool British voice sounded rather puzzled. ‘I’m sitting here on the tarmac waiting for the petrol truck, Sir.’ The ‘Sir’ didn’t stop him from ‘walking’ most of the next weekend.

The hazing and the strict discipline that we had endured for all of 1941 were relaxed during the last few weeks of our course. We were all more at ease with ourselves in the air and could actually look forward to receiving the coveted silver wings. We even mixed with the class of 41H during our more frequent sorties in to Albany and actually learned the ingredients of the awesome Zombie served at the Cadet Clubroom at the Gordon Hotel: one third dark rum, two thirds white rum, a little apricot brandy, pineapple juice, papaya juice, lime juice, sugar. Shake well then serve with a splash of dark rum on top. Lethal!

We were to meet quite a few of the Americans in the pubs of Lincolnshire when they came over with the ‘Mighty Eighth’ Air Force in 1942–43.

December 7th 1941 was a Sunday. It was a bright sunny morning, and normally, we would have been lazing around, but this morning was special. The RAF was joining forces with the US Army Air Corps at the local football stadium. We were giving the Americans a demonstration of RAF drill which, although not up to Guards’ standard, was still pretty good. The crisp, quick marching contrasted strongly with the more informal, and to us, sloppier style of the Americans and we were warmly applauded by the large crowd gathered there in the stadium.

We were standing there side by side with our American classmates with the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack fluttering together in the breeze when the PA system came alive. An emotional voice broke the news that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and consequently we were all in the war together.

The next few days, to us war-hardened veterans, bordered on panic. We were all confined to camp, and sirens would go off at all sorts of odd occasions. Security became almost paranoiac and heaven help you if you hadn’t got the right password when challenged, as you frequently were. Gradually, however, things got back to normal and RAF uniforms miraculously appeared and were issued anew to us.

On 3 January 1942 we filed into the camp theatre to receive from the major general commanding the Southeast Training Centre, General Walter R. Weaver, the hard-earned solid silver wings of the US Army Air Corps. We proudly wore them on the right breast of our tunics with the RAF wings (issued to us by Stores) in their proper position on the left. Later, in the UK we were forbidden to wear the US wings – an order conveniently ignored by most of us.

We celebrated our new status as fully qualified pilots with a gigantic party on the airfield. Dates for the evening ball were presented with orchids and gardenias in true American movie style and we danced the night away to ‘Amapola’, ‘You are my Sunshine’, ‘The Hut Sut Song’, ‘Frenesi’, ‘Elmer’s Tune’ and ‘Green Eyes’. We finished, of course, with ‘Off we go, into the wild blue yonder’ with its traditional and provocative ending; but there were no Upperclassmen there to retaliate. The evening before the ball we had celebrated with some drinks with our Instructors. My very good and kind Instructor, Lieutenant Millar, handed me the keys of his car when the beer ran low and told me to go and get a couple of cases. ‘But I can’t drive,’ I said. I was nineteen years old, could fly an aeroplane but had never driven a car.

Then it was a sad farewell to the still so peaceful South and back to face the harsh realities of wartime Britain.

CHAPTER SIX

We were soon shipped out of Georgia. I now had the rank of Sergeant Pilot. Those lucky enough to be given commissions were kept in the States to become Instructors. The US could never understand the British method of non-commissioned pilots and neither could I.