13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

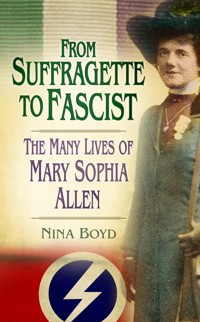

Mary Allen, once a window-smashing suffragette, went on to become a pioneer policewoman, helping create Britain's first female police force. Honoured for her work policing munitions factories and bombed towns during the First World War, she was soon infuriating the Establishment, travelling the world in her unauthorised uniform to the acclaim of foreign leaders and the dismay of the British government. Mary's head was next turned after a meeting with Hitler, and she joined Mosley's British Union of Fascists, narrowly escaping internment despite suspicions of spying, secret flights to Germany and Nazi salutes. The liaisons she formed with wealthy heiresses funded an extravagant lifestyle and the formation of a private army of women intended to save the country from Communist aerial attacks, nudity and white slavery. Although adored by her loyal friends, Mary was a stubborn, opinionated woman and today her achievements are overshadowed by the eccentricities of her later years. Citing documents specially released from the Home Office and sources contributed from Mary's own family, Nina Boyd has produced a fascinating account of this extraordinary woman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Preface

Acknowledgements

List of Abbreviations

Prologue

1 A Benevolent Dictatorship

2 This Suffragette Nonsense

3 Suffering in the Cause of Womankind

4 Nursed Back to Health

5 ‘Pollies!’

6 On Actual Police Duty

7 A Rude Disillusionment

8 Demands from Abroad

9 A Good Deal of Feminine Spite

10 White Slaves

11 An Accomplished Writer

12 Women Will Have To Be Used

13 A Hitler of the Spirit

14 Yellow and White Flowers

15 Helen’s Loss Has Taken Away All Joy In Life

Appendix I: Mary Allen’s ‘call to women’ issued in November 1933

Appendix II: Report on the search on 10 July 1940 of Mary’s home

References and Notes

Plate Section

Copyright

PREFACE

I first came across Mary Sophia Allen on a rainy day in Ripon, North Yorkshire, in 2001. Caught by a sudden downpour I took refuge in the nearby Prison and Police Museum. In a room full of helmets, whistles, handcuffs, police notebooks, dominated by a waxwork sergeant, the most interesting item was a postcard in a rack.

I took my postcard home and made a quick internet search of its subject. Mary Allen was a mystery: a fighter for women’s rights and an unsung hero of policing, who transformed herself into a political virago.

She was difficult to research, having been unmarried and childless; but distant relatives all over the world dug out memories and photographs. I am indebted to them all.

I cannot hope to rescue the reputation that Mary lost by her own wilfulness and folly. But I do believe that this opinionated, infuriating woman should not be entirely forgotten.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to the descendants of Mary’s siblings: Penny Gill and Rosemary Frouws in South Africa, and Margaret Bateman in Ireland; and to Vicky Tagart, who provided copies of family letters.

Also to the people at various organisations who answered requests for information, including The League of Women Voters, Buffalo, Niagara; Lynda James, Bereavement Services Advisor, Croydon; and the Public Record Office; and to the generous people who have given me additional information, including Pat Benham, Val Jackson, Joan Lock and Paul Ashdown.

And to those who read early attempts at a manuscript: Jill Liddington, Carola Luther and Andrew Biswell; Alan Henness, who helped me with my website; and my own supportive family, particularly John Bosley, Jacqueline Bosley, Maria Fernandez, Lynda Hulou, and Eleanor, Bill and Tom Boddington.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ASL

Artists’ Suffrage League

BJN

British Journal of Nursing

CLAC

Criminal Law Amendment Committee

DORA

Defence of the Realm Act

FANY

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

GWR

Great Western Railway

ILP

Independent Labour Party

IRA

Irish Republican Army

MWPP

Metropolitan Women Police Patrols

NUWSS

National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies

NUWW

National Union of Women Workers

NVA

National Vigilance Association

PRO

Public Record Office

WAS

Women’s Auxiliary Service

WFL

Women’s Freedom League

WPP

Women Police Patrols

WPS

Women’s Police Service

WPV

Women Police Volunteers

WSPU

Women’s Social and Political Union

WVP

Women Voluntary Patrols

PROLOGUE

In 1915, Mary Allen and her lover, Margaret Damer Dawson, had their hair cropped and posed for a photographer. They wore the uniforms they had designed for themselves as leaders of a newly formed women’s police service: military-style peaked caps, long greatcoats, tightly knotted ties and highly polished jackboots.

They are tall women, standing side by side in a formal pose, their feet positioned awkwardly at right angles. They take their roles as pioneer policewomen seriously; but at the same time, the nature of their relationship is apparent from the way they stand half-turned towards one another, the fingers of their white gloves intertwined. There is a hint of a smile on Mary’s face.

They had known each other for only a few months, but Margaret, who had no reason to know that she would only live another five years, had already made a will, leaving her substantial fortune to Mary.

In the seven years since she had been banished from her father’s comfortable home, Mary had observed the working of the law from all sides: as a suffragette she had been imprisoned three times and forcibly fed while on hunger strike; later she accompanied a deputation of members of Parliament on an inspection of conditions in Holloway Jail; and she became second-in-command to Margaret Damer Dawson in the first women’s police service. She took over as commandant of the Women’s Police Service after the death of Margaret.

Mary was a constant irritant to the Metropolitan Police Force which has effectively erased her from their history of women’s policing. She became well known in all corners of the world as the leading British policewoman, while the authorities at home no longer recognised her as any sort of policewoman. Curiously, she was asked in 1923 to advise the government on policing the post-First World War British occupation of Germany,long after she had been instructed by the same government to disband her police force.

After a meeting with Hitler, Mary embraced fascism and supported Oswald Mosley. She came close to being interned for her political activities in the 1940s. It may be that only her growing eccentricity saved her from detention.

Mary Allen’s story is extraordinary. She was a woman of whom it would be impossible for any liberal-minded reader to approve, but at the same time she inspired deep affection and loyalty from friends and family throughout her long and eventful life.

1

A BENEVOLENT DICTATORSHIP

We tend to remember the house we grew up in as being much bigger than it actually was; but Mary Allen’s childhood home was certainly substantial by modern standards. She was part of a household of two parents, ten children, and assorted nannies, governesses and servants, and they were not cramped for space:

As we grew older, boys and girls rode a velocipede around the garden paths, and on rainy days (forbidden joy!) even along the corridors. A velocipede! The name itself was an enchantment. Can any later invention provide a more fascinating suggestion of speed produced by short gyrating legs?1

Little is known of Mary’s childhood. She was always reticent about the details of her private life, in marked contrast with her partiality to self-advertisement in the public sphere. In her first volume of autobiography, The Pioneer Policewoman, she claims that she was ‘a very delicate child, educated almost entirely at home, and denied all the training in outdoor sports of the robust modern girl. Increased mental activity may possibly have been the result of this intolerable physical restraint.’2 Yet it was a busy, active childhood, fondly remembered fifty years later in A Woman at the Cross Roads, when Victorian values and the virtues of discipline and hard work had been replaced by what Mary perceived as dangerous libertarianism. ‘We invented games, made things, carpentered, jig-sawed, dug in the garden.’ (p.15) There were outings to a pantomime at Christmas, and three or four visits a year to the theatre, ‘either as a birthday treat or as a reward for good conduct’. (p.30) She describes a series of governesses, of varying quality and ability, but all respected and obeyed by their charges.

We might expect a childhood as apparently happy as Mary Allen’s to be recounted in more detail by a woman who wrote three autobiographies; but in none of them does she even tell us the first names of her brothers and sisters, or recall anecdotes from her earliest years. All she tells us is that her large family was not unusual, and that nannies were important figures, more present in the children’s lives than their parents:

From the age of two, or even earlier, we recognised a benevolent dictatorship – a discipline firm but not harsh (in spite of novels that make the exceptional seem the usual state of affairs). It was a brave child who would dare defy Nannie! … In looking back, it seems to me that we were very rarely punished. Not to be permitted to go down-stairs to join our parents in the real dining-room, to say good night, was a bitter humiliation. (pp.15–16)

Although Mary was educated mostly at home by governesses, she attended Princess Helena College, Ealing, when her father’s work took the family to London. The Princess Helena College was established in 1820 as one of England’s first academic schools for girls, founded for the daughters of officers who had served in the Napoleonic Wars, and the daughters of Anglican clergy. Mary gained a good education there judging by her literary output. Although her style is sometimes florid, she writes well, and displays a thorough knowledge of history. Mary is remembered in the annals of the college:

Another well-known figure in public life, Miss Mary Allen, the thrice-gaoled suffragette, returned to the College and talked to the girls about the Women’s Police, which she and a friend had launched. Sixty years later, in 1983, Marjory Lucas [a pupil in 1923] had still not forgotten the extraordinary visitor who ‘appeared large and important’ in uniform, hatted, ‘and sort of marched about’. But Miss Allen had yet to espouse the Fascist cause.3

Mary Sophia Allen was born on 12 March 1878 at 2 Marlborough Terrace in Roath, a suburb of Cardiff, not far from the divisional office of the Great Western Railway in St Mary Street, where her father was Railway Superintendent. Three years later, the family moved to a larger terraced house on four floors in nearby Oakfield Street.

Thomas Isaac Allen, Mary’s father, had entered the railway service when he was 15 years old, as a junior clerk. It was a boom time for ambitious young men, and he worked his way up to the position of Chief Superintendent of the Great Western Railway. He was much respected by his peers as a talented engineer, responsible for instituting a number of improvements in the GWR, including restaurant cars, better conditions for third-class passengers, steam heating of trains, and accelerated express services. His status within the GWR hierarchy is indicated by the fact that he represented the company on royal occasions. At the funeral of Queen Victoria in 1901, he accompanied the royal train from Paddington and, as one of the organisers of the event, he received a commemorative medal. The following year, he was photographed wearing a uniform specially designed for him for the Coronation of Edward VII. Thomas was then a fine-looking man in his early sixties, sporting a full white beard and luxuriant moustache.

In the notice of his retirement in the Great Western Railway Magazine, Thomas Allen is said to have filled the position of superintendent of the line ‘with great advantage to the company and much credit to himself … Mr Allen has always been keenly alive to the interests of the company, and also ever mindful of the welfare of the staff, with whom he is deservedly popular.’4

Thomas Allen’s position gave his family privileged access to railway travel, at home and abroad. His daughters travelled a great deal, and went to finishing school in Switzerland, and took music lessons in Germany.5 ‘When they travelled in England they had a special coach hitched on to the train they were travelling by. In Switzerland and France they were always met by railway officials who smoothed their paths.’6 Thomas died aged 72 years old in Brighton on 20 December 1911, having made a will three weeks earlier leaving everything to his wife. The net value of his estate was £1,987 18s 11d; the equivalent in 2012 of approximately £164,000.

Mary’s mother, Margaret Sophia Carlyle, came from a distinguished family, the Carlyles of Dumfries. She brought money and social cachet to the marriage. Her father was the Reverend Benjamin Fearnley Carlyle, vicar of Cam in Gloucestershire, who compiled a number of books of hymns and psalms. Margaret had two younger sisters, Anne and Dorothy, and an older brother, James, who was the father of another Benjamin Fearnley Carlyle, an eccentric charismatic character, who became known as Dom Aelred.

Margaret, Mary’s mother, went regularly and in secret to London to visit Mary after she was banished from the family home. She made her home in London after Thomas died. One of her granddaughters remembered:

We used to go from Edinburgh to London to Putney where she had a flat, to stay with her for holidays. I remember once we decided on the spur of the moment to go to Brussels to see Auntie Elsie who lived there and we gave grandmother ten minutes to get ready. When we were on the steamer we noticed that she had one black shoe on and one brown one and when we told her she said ‘That’s allright, nobody looks at an old lady like me’ and was quite unconcerned.7

Margaret Allen died in London in 1933.

Dom Aelred exerted considerable influence on his female cousins, one of whom, as we shall see, became a nun. Aelred began his professional life as a medical student at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, but he gave up medicine in order to become an Anglican Benedictine oblate. He took the name Aelred and founded the Benedictine community which, in 1906, settled on Caldey Island off the south-west coast of Wales:

Benjamin (Aelred) Carlyle, who had been fascinated by the monastic life since the age of fifteen, when he had founded a secret religious brotherhood at his public school … was a man of dynamic personality, hypnotic eyes, and extraordinary imagination. In 1906 his community made its permanent home on Caldey Island, off the coast of south Wales (outside Anglican diocesan jurisdiction), where, largely on borrowed money, he built a splendidly furnished monastery in a fanciful style of architecture. The life of this enclosed Benedictine community centred upon an ornate chapel where the thirty or so tonsured and cowled monks sang the monastic offices and celebrated Mass in Latin according to the Roman rite. As there was nothing like it anywhere else in the Church of England the island abbey inevitably became a resort for ecclesiastical sightseers, and many young men were drawn to join the community out of personal affection for Carlyle. The self-styled Lord Abbot of Caldey introduced practices into the life of his monastery which many outsiders, accustomed to the austere atmosphere of the existing Anglican men’s communities, found disconcerting … during the summer months they regularly went sea-bathing in the nude. Nor did Carlyle make any secret of his liking for charming young men.8

Aelred’s biographer, a former member of the Caldey Island community, remarked that spiritual friendships were ‘not discouraged’.9 In 1913 Aelred and a number of his monks renounced the Anglican Church and were received into the Roman Catholic Church. He spent some years working in the Canadian mission fields, but returned to his community and moved to Prinknash near Gloucester, where he is honoured as the founder of the present Benedictine community. He died in 1955, and is buried at Prinknash Abbey.10

Mary’s parents, Thomas and Margaret, had ten children, five girls and five boys, all but the youngest born in Cardiff. Bunty Martin, the daughter of their youngest daughter, Christine, said perhaps unfairly that ‘the girls of that family were the “go getters”. The brothers were very dull.’11

Thomas Fearnley Allen, Mary’s eldest brother, who bore a strong resemblance to his father, became an engineer, and settled in Argentina, where in 1885 he was appointed by the directors of the Buenos Aires and Rosario Railway as their Locomotive and Carriage Engineer and placed in charge of the shops at Campana. He married Ann Irving Lawrie, a descendant of one of the first Scottish settlers to arrive in the Argentine. They had three sons and a daughter. Some members of this branch of the family are still living in Argentina.

The second of Mary’s siblings, Henry Bevill, died when he was 11 months old. Her third brother, Arthur Denys Allen, known as Denys, ‘invented things’, according to his niece. ‘I met him once and he took us for a ride in his Model T Ford.’12 Another brother, Herbert, who became a master mariner, was killed in the First World War. Edward, the youngest of the Allen children, was born when the family had moved to Ealing.

The five Allen girls were energetic and outgoing. The eldest, Margaret Annie, was always known as Dolly. She is the person Mary refers to in The Pioneer Policewoman and Lady in Blue as ‘my sister, Mrs Hampton’. Dolly was involved with Mary in the setting up of the Women Police Volunteers (later renamed the Women Police Service), and was the only member of that service eventually employed by the Metropolitan Police, working at Richmond as an Inspector and probation officer. She had a daughter, Marjorie, and a son, called Wilfred after his father. Wilfred was a Polar explorer and pilot. He and his companions on a Greenland expedition were the first explorers ever to be awarded Polar Medals with both Arctic and Antarctic silver bars. Dolly was, like her sisters, attracted to religion, and she became a Christian Science practitioner.

Mary Sophia was the second daughter, and she was followed by Elsie, who married Herbert Joseph Cotton, a captain in the Indian Army. In 1911, Elsie and her daughter were living with her parents in Wraysbury, outside London, but her husband was absent, serving overseas. He died in Baghdad on 22 May 1916, having been taken prisoner by the Turks after the siege of Kut-al-Amara. Major Cotton was seriously ill with enteric fever when Kut surrendered at the end of April. Along with other sick officers, he was put on a steamer and sent up the river to Baghdad, a journey which took ten days. He died a few days after their arrival in Baghdad, and was buried in the Christian cemetery there. The cemetery has recently been destroyed in conflict. His possessions, apart from a few personal items kept back for his wife, were sold by auction in the cavalry barracks.13 Elsie remarried and lived for the rest of her life in Belgium.

Janet and Christine, Mary’s younger sisters, became involved in a strange and celebrated adventure. Both were inclined to the mystical, seeing visions and, in Christine’s case, practising automatic writing. They were two of the ‘three maidens’ who assisted Wellesley Tudor Pole in 1906 in his quest for the Holy Grail. (This story is told in Patrick Benham’s The Avalonians;14 and Gerry Fenge’s The Two Worlds of Wellesley Tudor Pole.15)

In 1885 J.A. Goodchild, a doctor with a winter practice in Italy, bought an old blue glass bowl from a tailor in Bordighera. Goodchild felt it might be the Holy Grail and, twelve years after buying the bowl, he had a psychic experience in which he was told to take it (he now called it ‘The Cup’) to Bride’s Hill at Glastonbury, where he hid it in a hollow under a stone in the waters of a well, confident that it would be found and understood as a holy relic. Several years passed, and Dr Goodchild began to wonder if he should do something to expedite the finding of ‘The Cup’. On one of his annual pilgrimages to the well, he found a note tied to a bush, left there by Kitty Tudor Pole, the sister of Wellesley Tudor Pole (a man he had already met), and he visited her at her home in Bristol.

Kitty’s friends, Janet and Christine Allen, and her brother, Wellesley, became involved in the affair. After a series of visions, Wellesley Tudor Pole became convinced that ‘something wonderful, remarkable, even Grail-like, was to be found at Glastonbury’, and that three maidens were needed to help him find it. Kitty, Janet and Christine Allen were willing volunteers. They had first met when Christine was 17. ‘The Allen girls were always considered beauties, and much in demand at parties, tall, slender and graceful, with golden hair and blue eyes.’16

Despite their fragile beauty, Wellesley Tudor Pole had no qualms about sending them to dig in 3ft of mud at Glastonbury, where they found ‘The Cup’, which became an object of reverence, kept in a room at Wellesley Tudor Pole’s house in Royal York Crescent, Clifton, Bristol. The room was designated the Oratory, and vigils were held there. Janet was particularly eager to spend hours in the Oratory: ‘We took three hours there at a time and six hours off night and day. It was rather sleepy work sometimes. At twelve every day, or rather 11.40, we had a special service, also smaller services at three and seven.’ It is alleged that baptisms and marriages were conducted in the Oratory, as well as a form of communion. According to Patrick Benham, Annie Kenney and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, two of the suffragists with whom Mary worked closely, visited the Oratory.17

Even Mary’s father, Thomas Isaac Allen, was caught up in these events, ‘arriving at the Oratory one morning “in rather a way”, to tell his two daughters that “he had dreamt of fire” and must warn them, especially Christine, “the younger one”, whose volatile nature was capable of attracting mishap’.18

Janet and Christine devoted much time to their research, visiting Rome and Iona together to investigate links between the Celtic and Roman churches; and Janet continued to correspond with Goodchild with whom she shared an interest in the theory that the Church of Rome was founded by a woman, and a belief in the power of gematria (the interpretation of Scripture through assigning numerical values to alphabetical letters).

This account shows that some members of Mary Allen’s family – including her father – were highly suggestible; but we should remember that many prominent and influential members of society dabbled in spiritualism and the occult at this time; some of them, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, taking supernatural beliefs extremely seriously. Sir William Crookes was a friend of the Allen family. He was both an eminent scientist – the discoverer of the metal thallium, who also refined methods of electric lighting – and a practising spiritist. He was an active member of the Society for Psychical Research, which investigated mediums and other psychic phenomena.

The events at Glastonbury were reported with a degree of scepticism by the Daily Express on 26 July 1907:

Being unable to spare time from his business to go to Glastonbury, Mr Tudor Pole sent his sister and two other ladies, one of whom is a ‘clairvoyante’, to the spot. Whatever the cup may be, the story has succeeded in stirring the greatest interest in the minds of men and women of distinction.

Wellesley Tudor Pole wrote a letter to the Daily Express the following day, in which he stated with breathtaking pomposity that:

The question of credulity or incredulity on the part of the public is a matter of absolute indifference to me, and I should like this known. Proof will be forthcoming in due course as the result of present research and in the interim the opinion of the world is valueless.

Janet was deeply interested in religion, spending much of her time in various retreats and pursuing the question of the ordination of women. In 1920, she was received into the Catholic Church at Westminster Cathedral, taking the names Margaret Brigid. The following year, she entered the enclosed Benedictine community at Stanbrook Abbey, Worcestershire, as a novice. ‘She is a convert, and about 40, and has always been very delicate, but a most sincere disposition, full of zeal.’ She made her solemn, perpetual vows on 24 June 1926: ‘Most of her family were present, although they declared they would never see her again … Commandant Allen, DBC [sic], sister of Sr. Brigid, was here.’19 Nuns at Stanbrook took the title ‘Dame’ once they had made solemn, perpetual vows. Dame Brigid continued her researches at Stanbrook, and kept in touch by letter with Kitty Tudor Pole. Her niece, Bunty Martin, wrote:

The last time I saw her was when she came to stay with us in Edinburgh in 1926 just prior to her taking final vows … I never saw Auntie Janet again but wrote to her frequently and received many letters from her telling us of the life she led and the funny things that happened to her – like the day she broke her chamber pot and had to take the pieces and lay them on the altar in the Chapel and ask God’s forgiveness for her carelessness. She said she felt rather foolish … She had a lovely sense of humour. Then we heard that she had cancer of the spine and was lying in a cold little cell, so we sent her a hotwater bottle and a bedjacket and we hoped that she would have been allowed to use them. We loved her very much.20

Those of her immediate family who visited Janet at Stanbrook found it ‘a most distressing occurrence going to see Auntie Janet who was behind bars, most upsetting it was’.21 Janet died in 1945.

Christine Allen, Mary’s youngest sister, was remembered by her daughter, Bunty Martin. Christine, ‘led quite an adventurous life for a girl of her time … My mother, Kitty [Tudor Pole] and Janet were very earnest young ladies with a Mission in life and my mother kept searching for the Truth until the day she died.’22 In 1911, the year of Thomas Allen’s death, Christine moved to Edinburgh. She married the artist John Duncan, a man some twenty years her senior, in the following year. They had two daughters: Bunty and Vivian. One of Duncan’s paintings, Saint Bride, shows angels with the faces of Janet and Christine carrying St Bride to the Holy Land. Like her older sister, Dolly, Christine joined Mary’s police force. Bunty recalled meeting Mary: ‘I first met her in Edinburgh in the early ’20s and thought she was a man. She had a monocle and was always dressed in uniform, jackboots and all.’23

Christine’s marriage to John Duncan ended in 1926. She sent her children to Belgium to stay with her sister, Elsie, while she decided what to do next. She shut her eyes and stuck a pin in a world map; the pin landed on Cape Town. So she borrowed £50 from another sister, Dolly, collected the children and set sail for South Africa, where she worked amongst the poor, setting up the Service Dining Rooms, which provided nourishing meals for a few cents. Bunty took over the Service Dining Rooms from her mother, and it is still providing food and a meeting place today.

Christine became a Christian Scientist in Cape Town:

Then that did not satisfy her and she joined some obscure religion, which she kept very secret … She believed in reincarnation and had great affinity with the Egyptians. She said in a previous incarnation that she had been one of the daughters of Aknaten. I am glad that when she came back the last time that her head had gone into shape again. You may remember that those little daughters had very peculiar egg shaped heads.24

Christine often came back to England, and became the first warden at the Chalice Well at Glastonbury in 1959. By this time she was a widow; her second husband, Colonel Sandeman, had died. In 1964, while visiting Chalice Well, she was called away to look after her sister, Mary, who she cared for until Mary died in the same year. Bunty said of her mother: ‘She was quite a girl … My two daughters loved her very much and she loved them.’25 Mary left the whole of her estate to Christine, who died in 1972.

In a photograph of some of the Allen family, taken when they were living in Bristol, Mary’s parents appear somewhat stern and forbidding. Margaret, her mother, is grey haired and rather worn looking; Thomas is still a fine figure, whom the years had treated more kindly. Of the four of their children in the photograph, Christine looks up almost fearfully at the photographer, while Janet, who is wearing a large cross, is gazing away from the camera with an abstracted look. Both are as attractive as their description in Gerry Fenge’s book suggests. The young man in the photograph is identified as Arthur Denys, the inventor, who has a humorous expression.

Evidently taken before Mary left home, the photograph has much to tell us. Although clearly posed by the photographer, it still suggests a bond between Mary and Janet, who has her arm draped across Mary’s shoulders, and Mary and Denys, whose elbow is on Mary’s knee. Mary herself shows no sign of the masculine appearance she adopted soon after leaving home: she is fashionably dressed, in a high-necked ruffled blouse, her hair arranged in an elaborate style. Her father is standing beside her, but with his back turned to her; her mother has an expression of long-suffering. Mary, square-jawed and rather plain, stares boldly at the camera. Her stubborn restless nature is evident from her taut posture and firm mouth.

Mary is not found anywhere on the 1901 census, when the Allen family were living at 39 Mount Avenue, Picton House, Ealing. She is heard of next in February 1909, by which time she is an active militant suffragette. In a court appearance, she gives her father’s address, 29 The Mount, Winterbourne, Bristol, although it is unlikely that she is actually living there.

In a studio portrait of Mary taken shortly after the family group, she looks younger than her 30 years: tall and slim in a tight-fitting overcoat, wearing a fashionable hat with a veil, a hunger strike medal pinned to her lapel. She carries a large satchel, stencilled with the words ‘VOTES FOR WOMEN 1d’. This is where Mary’s independent life begins.

2

THIS SUFFRAGETTE NONSENSE

‘As a girl I had lived in the west of England, in a home that was an ideal of security and peace. As was considered correct in my time and class, I had always dismissed with a delicate shudder the whole subject of Women’s Suffrage.’1

Mary Allen’s account of her leaving home to become a suffragette, written some thirty years after the event, is worth quoting at length, as it underlines some of her defining characteristics, including an obsession with her health, and her stubborn determination:

If I felt any criticism of home conditions, it was perhaps that [the] parental régime was somewhat strict, though it was lightened in my case because I was often ill, and it seemed that I might grow up to be a permanent semi-invalid. No one thought at that time that I would later accept a task needing so much activity and concentration that only an exceptional physique could enable me to carry it out.