Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Spellmount

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

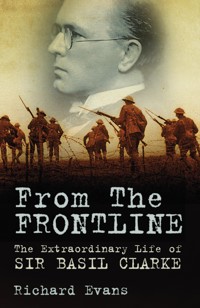

Sir Basil Clarke was a courageous and intrepid First World War newspaper correspondent. In late 1914 he defied a ban on reporters by living as an 'outlaw' in Dunkirk and by the time he was forced to leave was one of only two remaining journalists near the Front. Later in the war he reported from the Battle of the Somme and caused a global scandal by accusing the government of effectively 'feeding the Germans' by failing to properly enforce its naval blockade. Closer to home, he was the first to publish reports from the Easter Rising. Clarke became the UK's first public relations officer in 1917 and established the first PR firm in 1924. His public relations career included leading British propaganda during the Irish War of Independence, and his official response to Bloody Sunday in 1920 is still controversial today. In this, the first biography of Clarke, Richard Evans expertly portrays the life and character of this extraordinary man − a man who risked his life so that the public had independent news from the war and who became the father of the UK's public relations industry.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 501

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Abigail

Acknowledgements

Writing this book would have been impossible without the support of many people and I would like to say thank you to some of them. Most of all, I am grateful to Abigail Evans, my beautiful wife and the love of my life, who has been a huge support over the three years I spent writing it. It was just the two of us when I started and by the time it was completed our two wonderful children, Evelyn and Orson, had arrived, which gives an idea of what Abigail has taken on while I was spending days in libraries and archives or in front of a computer.

I would like to thank Jo De Vries and the team at The History Press for their faith in and support for the book, as well as Kathy Turner; David Gleed; Sandra Gleed; Lisa Day; Sheena Craig; and Lucie Jordon for reading various drafts and offering valuable advice. I am also extremely grateful for how Basil Clarke’s relatives Richard, Angela and Jim Hartley have been so generous in welcoming me into their home and giving me access to photographs and letters and a previously unknown first draft of his memoirs. Relatives from another branch of the family, Roger and Annie Bibbings, have also kindly given me photographs and documents and talked to me about Clarke, as have Colin Clarke and John Southworth.

I am also grateful for the help of staff at archives and libraries, including the British Library (the St Pancras site and the newspaper library at Colindale); the National Archives; the John Rylands Library in Manchester; the Royal Society of Arts; Manchester Grammar School; the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge; the Parliamentary Archives, King’s College London’s Archives and Special Collections; the Bodleian Library; the University of Oxford; the London Metropolitan Archives; and the Halifax and Canford School. Thanks, also, to Peter Howlett of the London School of Economics and the historian Judith Moore for their information and guidance.

And a very special mention goes to my mum and dad, Dee and Brian Evans. Not only did they both read the book and suggest changes, but without their huge support throughout my life I would never have got around to writing it. I hope it goes part of the way towards making up for the mess I made of my history degree.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Prologue: ‘The Austrians are here’

1 Into Journalism

2 The Manchester Guardian

3 The Daily Mail

4 Canada

5 To War

6 ‘A Sort of Nightmare’

7 Ypres

8 Eastern Front

9 Home Front

10 ‘We are Feeding the Germans’

11 Leaving the Mail

12 The Somme

13 Into Government

14 Ireland

15 Bloody Sunday

16 ‘Propaganda by News’

17 Truce to Treaty

18 Back at the Ministry of Health

19 Editorial Services Ltd

20 Business

21 The ‘Publicity Journalist’

22 What Really Matters’

23 The ‘Doyen’ of Public Relations

Plates

Copyright

Prologue: ‘The Austrians Are Here’

‘Get up, get up, sir! The Austrians are here!’

Basil Clarke heard the voice coming into his dream and then a few seconds later was woken suddenly by the feeling of hot wax hitting his wrist. It had dripped from the candle that the night porter was holding over him.

As his eyes adjusted to the light, his Romanian assistant Dobias came running into the room. ‘Get up, get up!’ he shouted frantically. ‘What can you be dreaming of, to lie still so? You will get me murdered and yourself, too, if you don’t make haste!’

Clarke tried to get them to tell him how long ago the Austrians had arrived but both men were incoherent with panic. So he got out of bed and began to dress, doing so deliberately slowly in the hope that this might help calm Dobias. Looking back on the incident later, though, he would admit that ‘I was pretty scared, too, inwardly’.1

***

It was February 1915. Clarke and Dobias were in Chernivtsi, a city in present-day Ukraine that had already changed hands between the Austrians and the Russians several times during the first seven months of the First World War.

When they had arrived the previous day, Chernivtsi had been under Russian control but was gripped by an atmosphere of ‘brooding uncertainty’ because of a rumour that the Russians, who were fighting on the side of Britain and France, were about to withdraw and let the Austrians retake the city.

Clarke and Dobias visited the Russian Army headquarters to try to discover if the rumour was true, but the first official they asked was unable to give them any useful information. Clarke noted with concern, though, how he would abruptly stop speaking in the middle of a sentence to listen to the sound of the Austrian guns in the distance, as if trying to judge how far away they were. But a Russian soldier later assured him that as a newspaper correspondent he would be told in advance about any order to withdraw and so he and Dobias found a hotel for the night.

Clarke planned to spend the evening in the city after dropping off their luggage, but they were stopped at the front door of the hotel by a Russian sentry with a bayonet who told them that no one was allowed outside after 6.00 p.m. The hotel did not have a restaurant so they ate ham and bread with a bottle of Austrian wine in Clarke’s room and then Dobias returned to his own room while Clarke stayed up writing by candlelight until 11.00 p.m. Just before he went to bed he visited the night porter, whom he gave a large tip in exchange for a promise to wake him immediately at any sign of movement of troops or shooting in the streets.

But the night porter fell asleep and by the time he woke up the Russians had withdrawn and the Austrians were already starting to arrive in the city. This meant Clarke was now behind enemy lines.

He and Dobias hurriedly paid their hotel bill and the night porter ushered them to the front door, opening it but then quickly closing it again at the sound of movement outside. The three men looked through the glass panels of the door and saw snow-covered soldiers marching past. The night porter waited until the soldiers had passed before opening the door again, looking up and down the street and then pushing Clarke and Dobias down the steps and closing the door behind them. They were on their own.

They decided to head north towards the River Prut, as this was the way the Russians were likely to have left the city. But after a few hundred yards there was a large explosion in the distance ahead of them that they thought must be the Russians blowing up the bridge. So with that escape route now closed to them, they instead began to head in the direction of the Romanian border, from where they had arrived the previous day. After seeing a man who they thought was carrying a bayonet, they decided it would be safest to stay off the roads and so they climbed over fences and ran through fields and gardens until there was just countryside between them and Marmornitza, the border village they had come from.

Marmornitza was less than 10 miles from Chernivtsi but the journey meant trudging through snow that was so deep that they were only able to keep to the road by following the telegraph poles in front of them. As well as the threat of capture by the Austrians, Clarke and Dobias spent the journey anxiously looking out for the wolves they had been told roamed the area. In the event, the only animal they encountered was an angry farm dog whom they took turns fending off with a stick while the other man lowered a bucket into a well to get a drink of water.

It was morning when they finally arrived at the Romanian border after five hours of walking and, tired and hungry, they went straight to a restaurant to get breakfast. By the time they finished their meal, just an hour after crossing the border, they returned to see that hundreds of Austrian soldiers were now on the other side.

***

Just a year before, Clarke had been the Daily Mail’s northern England correspondent, writing about subjects as mundane as the trend for built-in furniture2 and the increasing popularity of communal living as a way of minimising housework.3

But though the war was less than a year old, he was already well-used to living by his wits by the time he came to make escape from the Austrian Army in the middle of the night. He had been hardened by the experience of living as a fugitive in Belgium and France during the first few months of the war, under the dual threat of arrest by the Allies and sudden death from a German shell. While the period he had spent in Flanders as what he described as a ‘journalistic outlaw’ may have only lasted some three months, it had exposed him to more danger and hardship than most journalists face in their entire careers.

Notes

1The War Illustrated, 2 December 1916, p.363–4, Also Basil Clarke, My Round of the War, London 1917, pp.128–30. In some versions of this story, he and Dobias were chased by two Austrian soldiers during the last part of the journey.

2Daily Mail, 3 March 1914, p.6.

3Daily Mail, 9 February 1914, p.6.

1

Into Journalism

As the son of a shepherd, it was a considerable achievement that by the time James Clarke came to having children of his own in the 1870s, he and his wife Sarah were running a chemist’s shop in the affluent Cheshire town of Altrincham and were comfortable enough to employ two servants.

It was the third of their five children, a boy born on 11 August 1879, who would go on to complete the family’s vertiginous social rise by becoming both a celebrated journalist and pioneer of a new profession that would change the nature of journalism itself.

When considering those who have led remarkable lives, there is always the temptation to over-interpret aspects of their childhood that might mark them out as special. Certainly, there was nothing about the circumstances Thomas Basil Clarke was born into that hinted at what lay ahead of him.

Yet from an early age, Clarke was undoubtedly different. For his parents, this difference lay in his musicality: while still a toddler he would play tunes by ear on the family piano and sing songs in local shops in exchange for sweets. The historian, on the other hand, may be more likely to see his early wanderlust – as a young child he boarded a train on his own that took him as far as Manchester and a few weeks later sneaked onto a steam boat at Blackpool – as the reason for the extraordinary course of his life.1

But for Clarke himself, what gave him the strong feeling of being set apart from other children was the fact that he only had one eye. The disfigurement bestowed him with a kind of celebrity, as children would be either sympathetic because of the incorrect assumption that having an empty eye socket must be painful, or curious to discover how the eye had been lost. Clarke himself never learned the truth of what had happened because he had been too young to remember and his parents would change the subject whenever he asked about it. He was not, though, about to let his lack of knowledge on the subject detract from the attention it brought him and he would invent far-fetched stories about it; one particularly fanciful version was so heartrending that it reduced a pretty classmate to tears and led to an invitation to her house for tea.

The loss of an eye never caused Clarke any great difficulties, though it did mean that at the age of six he had to endure having a glass eye fitted. The traumatic memory of an elderly man with shaky hands trying to fit lots of different glass eyes to find one that was the right size and colour would stay with him for the rest of his life. It was the ones that were too big that were worst, causing Clarke to cry out in pain as the old man tried to push them into the socket. Eventually, his father ended the ordeal by opting for the more expensive option of having some specially made.

His new glass eye only added to Clarke’s local fame, with people regularly stopping him in the street to ask to see it. He was usually happy to oblige, though it proved an expensive form of showing off as his inability to keep a firm grip meant that, as he later wrote, ‘more than one dainty sample of the shaky-fingered old gentleman’s fragile wares has gone tinkling to the pavement to smash into a thousand fragments’.

His disfigurement may have made him feel special as a young boy, but his experience of the education system led to him feeling singled out in a less pleasant way. His father was passionate about the importance of education – he paid for lessons with a local teacher just so that he would be able to talk to his children about their studies – and when Clarke reached the age of eleven he was sent to Manchester Grammar School as a day boarder.

It was a standard of schooling his family could barely afford, but the money they spent on it was largely wasted. His first day got off to a bad start when the teacher told the class that ‘all Clarkes are knaves’ and then proceeded to publicly ridicule his attempts at Latin. This humiliation set the tone for a school career in which Clarke defied authority as much as possible and was haunted by what he described as an ‘indefinable but never-easing load on the mind and bleakness of prospect before me’. Not surprisingly, this resulted in an inconsistent school record. He enjoyed sport and music, both of which he showed a real talent for, and he managed to show some academic promise by coming second out of fifteen boys in Latin in his first two terms, and top of his form in physics at the age of fourteen. But at the same time as he was excelling at physics, he had fallen to twenty-first out of twenty-two boys in Latin and even in English, the subject most closely associated with journalism, he finished bottom of his form in both the summer and winter of 1894.2

Even half a century later and with a successful career behind him to insulate him against the memory of it, Clarke would still feel bitter about the way he was treated on that first day at Manchester Grammar School.

‘I find it difficult … to look back with anything but contempt on the man who could so self-satisfiedly knock the heart and zest out of a small ill-taught boy,’ he wrote. ‘I can see now that this teacher had a disastrous effect on my school life and character.’

Given how focused Clarke’s father was on his children’s education, it is not surprising that he was disappointed by Clarke’s attitude towards school and Clarke later admitted that ‘it must have nearly broke his heart to see me frittering away opportunities’.

***

For reasons Clarke never discovered, his father had a visceral loathing of the banking profession that was so intense he would often refer to a job in a bank as a kind of shorthand when talking about professional and personal failure. When he was given news about Clarke’s rebellious attitude at school, for example, he would warn him that ‘I shall certainly see you with a pen behind your ear perched on a banker’s high stool one of these days, my boy’. So it was with a sense of shame that, on leaving school at the age of sixteen in the summer of 1896, Clarke took a job as a junior clerk at a Manchester branch of Paris Bank Limited,3 although his acceptance of it was as much to do with the modest working hours giving him time to practice music as it was the result of his poor school record. His father did not live to see what would have been, to him at least, Clarke’s disgrace. He had died the previous year.

Clarke hated the job in the bank, finding it not only boring but also physically exhausting because it involved carrying heavy bags filled with ledgers and coins. There were, though, other things to occupy his mind. As well as playing for Manchester Rugby Club, in 1897 he started a long-distance degree in music and classics at Oxford University that gave him the chance to study under Sir John Stainer, best known for his arrangements of Christmas carols such as God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen, and Sir Hubert Parry, who composed the popular hymn Jerusalem. There is no record of Clarke completing any exams during his time at Oxford; he would later claim that he dropped out as a result of his father’s death,4 though this seems unlikely as his father had actually died two years before he started his degree.

Perhaps the real reason was that he was unable to mix the demands of a degree with a draining full-time job, though the work at the bank did become easier when he was transferred to a small branch where his manager was the only other employee. As well as the work not being as physically tough, he discovered that he and his manager shared a mutual love of Gilbert and Sullivan and they eased the boredom by inventing a game where one man would sing a line and then the other would have to sing the line that came next. It may have passed the time, though Clarke later admitted that ‘these little interludes, though cheery enough, were hardly conducive to accuracy of work’. Eventually, he was transferred again to another branch and his relationship with his new manager was much less amiable; he was fired after responding to the manager’s rebuke that he was an ‘impudent young man’ by telling him that it was preferable to being ‘a foolish old one’.

A job at the City of Glasgow Assurance Company in Manchester followed, but this proved no more successful in instilling in him a love of banking and he left after a year, complaining that he found it ‘uncongenial’.5 With no job apart from a part-time position as an organist in a local church, he started sending music he had written to publishers in the hope of becoming a professional composer. He even tried his hand as a travelling salesman by trying to sell sheet music of a song he had previously had published at his own expense. Called ‘Morning Song’, it was a poem by the nineteenth-century poet Allan Cunningham that Clarke had set to music. Though he never made his money back on it, the expense was justified some years later when he was walking past a house and felt a great thrill when he heard it being played on the piano inside.

It was around this time, on 14 April 1902 and with Clarke now twenty-two, that his sweetheart Alice Camden gave birth to a baby boy they called Arthur. The arrival of their first child meant Clarke’s need for a job was all the more pressing, and so when Arthur was just under a year old Clarke travelled to London for the first time to try to secure a job playing piano at a West End theatre. He was unsuccessful, but during his stay in the capital he met a German man who was looking for people to teach English in Germany.

Clarke was initially sceptical, not least because his inability to speak German made him question how useful he was likely to be, but his prospective employer assured him this would actually be an advantage and so Clarke took a boat to the Netherlands and then travelled on by train to Hirschberg in Germany. There, he made his way to the Bokert Academy, an establishment whose rather grand-sounding name belied the fact that it was based in a small house, and met its French proprietors, two men called Bokert and Prunier who Clarke took an instant dislike to.

Perhaps surprisingly, there was actually a job for him there, though shortly after he started work he began to wonder how Bokert and Prunier were able to afford his wages given the small number of students he taught. He was right to be worried; before long his employment came to a bizarre end, and one he came to believe was engineered as a pretext for getting him off the payroll, when Prunier accused him of knocking on doors in the town and running away. In the confrontation that followed, Clarke gave Prunier a ‘flat-handed clout’ and Prunier retaliated with a kick to the head that Clarke described as a ‘dangerous little sample of the “savat” fighting for which you have always to keep a bright lookout when exchanging fisticuffs with a Frenchman’. Though the kick was sufficiently powerful for Clarke to think ‘it would probably have broken my jaw had it landed’, he managed to catch his opponent’s heel and the momentum of the kick, aided by a shove from Clarke, sent Prunier onto his back, smashing a glass door in the process. Bokert, who had been watching the fight, left the room and returned a moment later with a gun and shouted at Clarke to ‘allez’.

‘I have done many silly things in my life,’ Clarke later wrote, ‘but I have never yet argued against a revolver.’

He left, though he did return later to demand his unpaid wages. He threatened to go to the police if they refused and they eventually gave him the money they owed him, though only after deducting the cost of a new pane for the glass door.

Clarke’s fight with Prunier is the first known example of the violent temper that would be a feature of his adult life, but it was not his only confrontation during his time in Germany. No one could accuse him of picking on easy targets. He was later told he was lucky not to have been put through with a sword after he insulted a drunken German officer, while on another occasion he was attacked and thrown in a river by some German soldiers he had got into an argument with.

After the job at the Bokert Academy ended, he continued teaching English but made such little money that he could barely afford food and cigarettes, and paying for a ticket back to England was out of the question. But things improved when he got a job playing piano in a small theatre orchestra and he also started giving swimming lessons. Then when the summer ended and it got colder, he ended the swimming lessons and started teaching boxing instead.6

He described living abroad as a ‘good life’, though it was more the existence of a young man without responsibilities than that of the father of a young son. Perhaps it was the inevitable fulfilment of the need to travel that he had felt since he had boarded the train to Manchester as a toddler. Certainly, looking after children on her own was something that Alice would have to get used to. She and Clarke would go on to have a large family and his thirst for adventure, probably more so than the demands of his career, meant he spent long periods of their upbringing away from home.

***

Clarke returned from Germany near the end of 1903. The time spent apart from Alice does not seem to have diminished his feelings for her and as soon as was practically possible, on 4 February 1904, the couple married in Altrincham.

A plain-talking woman, Alice responded to his proposal of marriage with a characteristically matter-of-fact ‘all right’.7 There is little doubt that her acceptance of his proposal was one of the best things that ever happened to Clarke. Alice would be a loving – and sometimes long-suffering, given the amount of time he spent overseas – companion until the end of his life and was known for her kindness and warmth.

One of the witnesses at the wedding was Clarke’s friend Herbert Sidebotham, who he had met at Manchester Grammar School when Sidebotham had been a prefect and Clarke had thrown a screwed up piece of paper at his head. Sidebotham’s decision that calling Clarke a ‘silly ass’ was sufficient punishment proved to be the start of a lifelong friendship.8

Sidebotham, a scholarly figure who studied at Balliol College before becoming a journalist for the Manchester Guardian, would go on to play an important role in setting the direction of Clarke’s career. But Clarke’s initial brush with journalism happened entirely by accident.

He had re-joined Manchester Rugby Club shortly after arriving back in England and was at an evening team selection meeting in a local hotel when three men who had just finished dining began to sing a quartet from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado. Clarke realised that the lack of a fourth singer meant most of the chords were missing a note and, knowing the words to Gilbert and Sullivan’s oeuvre almost by heart, he decided to join in. When the song was finished, one of the men thanked Clarke and in the conversation that followed Clarke mentioned he was a church organist. The man replied that he was editor of Manchester’s Evening Chronicle and asked Clarke if he would be interested in writing an article for it.

Clarke had never before even considered the possibility of a career in journalism and, somewhat shocked by the offer, asked what the article should be about.

‘Write it, my boy, on good music and how to appreciate it,’ the editor replied. ‘Just write me a column saying simply and clearly what you feel you’d like to say about it to someone you liked. And … let me have it in my office by … noon tomorrow without fail.’

It was already gone 10.00 p.m., so Clarke went straight home and, fuelled by large quantities of coffee, began to write. He finished the first draft of the article at around 3.00 a.m. but he was not happy with it and so started again from scratch. The sun was already beginning to rise when he completed the second draft but he was still not satisfied and so began a third and, it transpired, final draft, which he delivered to the Evening Chronicle’s office with just 10 minutes to spare before the midday deadline.

Clarke bought the newspaper the following evening and saw his work, barely changed, on the page with the initials ‘B.C.’ at the bottom. It gave him a huge amount of pride. ‘That “first-article-in-print” feeling,’ he later wrote, ‘surely it is the masculine counterpart of the feminine “first baby” complex.’

But as great as the sense of achievement he felt at becoming a published writer may have been, it might not have led anywhere had it not been for Sidebotham. The two men were taking an afternoon walk about two weeks later when Sidebotham suddenly turned to him.

‘Basil,’ he said, ‘I’ve been thinking that we ought to make a journalist of you.’

Clarke was surprised and more than a little flattered that someone he respected as much as Sidebotham thought he had the potential to be a successful journalist. As well as boosting his confidence, Sidebotham also gave him the practical advice that he should get six months’ experience on any newspaper that would have him and to then come and see him.

After a number of unsuccessful requests to newspapers in London to employ him on a nominal salary, Clarke managed to persuade the Conservative Party-supporting Manchester Courier to give him a job as a volunteer sub-editor.9 On his first day, he was given an article and told to ‘revise and shove some headlines on that’. And that is broadly what he did for the next six months, learning the skills of sub-editing as he turned journalists’ raw copy into the finished product that appeared on the page. He found that he enjoyed life in a newspaper office. He appreciated the fact that his fellow sub-editors were experienced and talented newspapermen and he also relished the camaraderie of life in a newsroom; after working through the night he and his colleagues would often stop at the pub on the way home for a 6.00 a.m. pint of beer.

By the end of his placement, he had made a good impression on his colleagues. His news editor praised his ‘enthusiasm, assiduity, and adaptability’ and congratulated him on the speed with which he had learned the sub-editors’ craft.10 He was offered a permanent job but Sidebotham advised him to aim higher and to instead apply for a position at the more prestigious Manchester Guardian.

After years of aimless drifting, Clarke’s career finally had a sense of direction. His family life was going well too, as he and Alice had another son, John, who would be followed a year later by a third son, whom they named Basil Camden but called Pip to distinguish him from his father.

Fatherhood suited Clarke; his friend James Lansdale Hodson later wrote that ‘if a lad had the choosing of a father I cannot think of a better one than Basil’.11 There is no doubt he adored his children. ‘What married people get, in return for not having kiddies I don’t know,’ he wrote home to Alice on one of his many trips abroad, ‘but whatever it is, whether fame or position or pleasure or merely wealth, it is jolly well not worth it.’12

Notes

1 These two stories come from a previously unknown draft of Clarke’s autobiography. It has been kindly given to the author by the Hartley family, who are descendants of Clarke. Its contents are being made public here for the first time. Unless otherwise stated, all the personal information about Clarke’s early life comes from this source.

2 Details of Clarke’s academic record were previously unknown and are from correspondence between the author and Manchester Grammar School’s archive.

3Financial Times, 10 March 1923, p.4. This article contains details, not included in Clarke’s autobiography, of his start date at the bank.

4 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/4/500, letter from Clarke to the Manchester Guardian, 14 June 1904.

5 Ibid.

6Sheffield Independent, 5 September 1919, p.4.

7 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, p.63.

8Daily Sketch, 20 March 1940, p.10.

9 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/8, Letter from Clarke to C.P. Scott, 11 October 1916.

10 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/1, Testimonial from F.J. Coller, news editor of the Manchester Courier, to Clarke.

11 James Lansdale Hodson, Home Front, London, 1944, p.118.

12 Letter from Clarke to Alice, Amsterdam, 11 October, 1915. This letter is the property of the Hartley family and its contents are being made public here for the first time.

2

The Manchester Guardian

The Manchester Guardian started life in 1821 as a local newspaper that was established in response to the Peterloo Massacre and the campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws. But by the time Clarke applied for a job there, it was already a significant way through the transformation that would see it move to London in 1964 – it truncated its name to The Guardian – and with the advent of the Internet become one of the most widely read English-language newspapers in the world.

A large part of the reason for this remarkable journey was C.P. Scott, the legendary editor and owner who presided over it for more than half a century and whose bust is still displayed at The Guardian’s office today.

It was Scott that the 24-year-old Clarke wrote to in 1904 to apply for a position as a sub-editor, supplementing his application letter with references from the Manchester Courier and from Herbert Sidebotham.

‘I have formed a very high opinion of Mr Basil Clarke’s natural ability,’ Sidebotham wrote, before going on to describe him as ‘a man who in my opinion might go very far indeed in journalism’ because of his ‘remarkable capacity for assimilating new ideas’ and the ‘industry and zeal which come from keen interest in his work’. Clarke had ‘direct personal knowledge of men and things,’ Sidebotham added, along with ‘ready sympathies and a keen eye for the human side of current affairs’.1

Given such effusive praise from an existing member of staff, it is not surprising that Clarke got the job. He joined the sub-editors’ room and, though he found the work challenging and the expectations high, he quickly grew to love the idealistic spirit that characterised the Manchester Guardian and which still sets The Guardian apart from the rest of the newspaper industry today. He also enjoyed being surrounded by men of intelligence and culture – his fellow employees included the future Poet Laureate John Masefield – and he welcomed the chance to work with some of the finest sub-editors in the country. And he and his fellow sub-editors got on so well that they would often go walking together or play tennis before work, and on Saturday evenings would congregate at one of their homes.

As well as editing the work of others, Clarke also got the opportunity to write occasional articles of his own. In 1906, for example, he wrote about his experience of having to appear at Manchester Police Court after his chimney caught fire and the smoke attracted the attention of a zealous police officer. The article was a whimsical account of what it was like to stand in the dock alongside criminals, and it was so well-received that he got a bonus that not only covered his fine but left him with enough money to take Alice for tea and cakes at a fashionable restaurant.2 The tone of the article was mostly light-hearted, but it also contained the alarming admission that when a ‘small-eyed youth with lower jaw hung like a rag’ arrogantly asked him why he was in court, ‘an impulse seized me to dash him to the floor’, suggesting that a steady career and a settled home life had not made Clarke any less combative.3

This and the other articles he wrote appear to have given him a taste for it and in 1907 he wrote to C.P. Scott to ask to switch to a reporting role. ‘I might eventually go further as a reporter than as a sub-editor,’ he suggested. ‘Mr Sidebotham says that my individuality would have better scope.’4 But Clarke, who found Scott a ‘formidable and rather terrifying’ figure,5 was also careful to avoid creating the impression that he was unhappy with life as a sub-editor. ‘I am very comfortable in the sub-editors room and have no reason for dissatisfaction of any kind,’ he insisted. ‘My relations with everyone are of the happiest and the work is quite congenial.’

The reply from Scott must have expressed concern about his lack of shorthand because, two days later, Clarke wrote to him again promising to ‘make all the haste I can to become proficient’. ‘Till then I could be given engagements that did not demand much verbatim note-taking,’ he suggested. ‘I might get along all right, I think.’6

This second letter was enough to secure him a reporter’s job and if his lack of shorthand meant the appointment was a gamble, it was one that paid off. While the claim by one of his colleagues that Clarke was ‘one of the Manchester Guardian’s most brilliant special correspondents’7 may have been an exaggeration, he was certainly successful and became known for his descriptive writing ability in particular. When he visited Edinburgh for the first time to report on a rugby match, for example, he devoted as much space in his match report to describing his impressions of the city as he did to the rugby, including the memorable line that Princes Street was ‘the vision of an architect not past his dreaming days’.8 When the article was published, a Scottish colleague wrote to Clarke to congratulate him on it, joking that Clarke had done a better job of capturing the appeal of Edinburgh in a single morning than he had managed in his entire career.9

Equally, Clarke’s news reporting style was clear and to the point, thanks in part to Sidebotham’s advice to him that everything he wrote should meet three tests:

Is that exactly what I meant to say, neither more nor less? Could any person – wise man, knave or fool – construe it to mean anything different from what I meant to say, either more or less? Could I have made it more easy for the reader to understand what I meant him to understand?

It was this diligence that led to him making a success of an interview with Ernest Rutherford, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who later became the first person to split the atom. On meeting Clarke, Rutherford told him to ‘ask me questions in schoolboy language and I will reply in schoolboy language’, which suggested he did not have much confidence in Clarke’s ability to grasp the finer points of his work. But the first draft of the article Clarke sent him to check its accuracy impressed him enough that he did not change a single word.10

As accomplished as Clarke’s writing may have been, it was not something that came easily. One of his colleagues wrote:

His stuff is clean and direct and is the product of great painstaking. I have known him to write and rewrite passages in his articles over and over again until he was satisfied with them. He once spent nine or 10 hours on a backpager. They are usually very laborious but they succeed – they are finished and don’t show the traces of his labour. None of his writing with us was ever spoiled by hasty or slipshod work: he is about the only man I ever knew who set out deliberately from nothing to become a good descriptive writer and succeeded out-and-out.11

***

As well as standing out for the quality of his writing, Clarke also had the resourcefulness and tenacity needed to be a successful reporter. For example, when the Midlands Railways Company refused to comment on rumours that it was secretly employing men to act as strike breakers, Clarke got a tip off from a railway worker over a pint of beer and, after a cross-country horse and carriage ride and a scramble up the banks of a railway line, he eventually found a camp where the men were staying.12

It was these qualities that led to a meeting with a future Prime Minister. David Lloyd George, who was then making a formidable reputation for himself as President of the Board of Trade in Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s Liberal Government, was in Manchester to negotiate with striking cotton workers.13 There had been no sign of an agreement and at 12.30 a.m. C.P. Scott appeared ‘almost shyly’ in the reporter’s room – it was the only time Clarke ever saw him there – and told Clarke he did not want to leave for the night if Lloyd George was about to secure a deal.

‘I hardly like to go home leaving him still at it,’ Scott said. ‘You’ll never know what that amazing man will pull off or when he’ll do it.’

So Clarke was sent to the hotel where Lloyd George was staying to find out if an agreement was likely to be reached that night. He arrived to find about thirty reporters waiting for news, but rather than joining them he asked at reception for Lloyd George’s room number and, surprisingly, they gave it to him. So he went to the fourth-floor room and knocked on the door.

‘Come in,’ came a voice from inside. Clarke opened the door and was confronted by a man he later described as a ‘little dapper secretary person’ who he assumed was a civil servant.

‘Who are you?’ the man screamed.

Clarke explained he was a journalist.

‘How dare you come into Mr Lloyd George’s room?’ the man shouted. ‘How dare you?’

At this point, Lloyd George rose from the chair he was sitting in and walked across the room towards Clarke.

‘What is it, my boy?’ he asked.

Clarke told him how Scott had sent him to find out if an agreement was imminent.

‘Tell him with my compliments that I don’t think there is any chance whatever of that tonight,’ Lloyd George replied.

He put a hand on Clarke’s shoulder. ‘My boy, don’t be upset about what my colleague said as you came in,’ he said. ‘We’ve had a very tiring day. And my boy, you’ll make a very good reporter.’

***

Clarke may have taken the rebuke from the civil servant in his stride, but another industrial dispute once again showed his pugnacity.

On the same day the Manchester Guardian published an article by Clarke that he admitted contained some ‘very plain’ comments about the employers in a dispute, he telephoned the company’s chairman to get some more information.

‘Are you the man who wrote that article about the strike in this morning’s Manchester Guardian?’ the chairman asked.

Clarke replied that he was.

‘Well if you ever come within reach of me, I’ll knock your bloody head off,’ the chairman replied.

It is not especially unusual for journalists to be threatened with violence by those they write about and the normal response is to try to stay out of the person’s way until they calm down. Instead, Clarke found the nearest taxi and went straight to the chairman’s home to confront him.

He knocked confidently on the door, assuming that the chairman would not be a match for him in a fight. But when it opened he was surprised to discover that the chairman was a ‘wild-looking, outsized Irishman’.

‘I feared the worst,’ he later recalled. ‘He glared at me for some minutes, then he asked me to sit down … and have some tea! And nothing was said, or done, about my head.’14

The two men ended up discussing possible solutions to the industrial dispute and Clarke put forward an idea for a compromise that might suit both parties. The chairman said he would submit it to his fellow employers and this promise gave Clarke another story as he broke the news of a ‘possible way out’.15

***

While Clarke covered a wide range of subjects for the Manchester Guardian, his main interest was in aviation. The early twentieth century was a period of great technological advance and in no field was progress more exciting than that of powered flight. It had first been achieved by the Wright brothers in 1903 – the year Clarke had travelled to Germany – and the first powered flight in Britain was in 1908, the year after Clarke became a reporter.

Its combination of danger and sense of wonder meant aviation was well-suited to Clarke’s descriptive writing style. Air travel may seem mundane today, but Clarke’s description of French pilot Louis Paulhan negotiating strong winds at a hugely anticipated air show in Blackpool in 1909 captured the sense of awe the new technology inspired:

What a strange and admirable sight to see a man poising himself among the winds and sailing on that tempestuous highway perched only on the edge of certain square feet of canvas stretched on bars of wood, with emptiness in front and behind, and the wind whistling among the wires and struts which hold him together from destruction!

And all this vigilance in balance, all this battle with air currents, is carried on by a single lever moving every way at Paulhan’s right hand. On the strain endured by one arm – and to move the planes when winds are against you is not done without some force – depends the safety of M Paulhan and his machine.16

It was this article that first brought Clarke to the attention of Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the Daily Mail and the man who had first suggested the idea of an aviation week to Blackpool Town Hall after being inspired by a similar event in France. ‘We ought to have that man on our paper,’ Northcliffe is said to have remarked about Clarke when he read it.17

***

On 12 July 1910, nine months after his article about Paulhan, Clarke attended an air show at Bournemouth. He probably saw the assignment as little more than another chance to showcase his descriptive writing skills, but it proved to be by far his biggest story for the Manchester Guardian.

Among those flying was Charles Rolls, the 32-year-old co-founder of the luxury car manufacturer Rolls-Royce. Aviation had by now replaced the automobile as Rolls’s main interest, and shortly before the Bournemouth show he had become the first man to complete a non-stop double crossing of the English Channel.

A few days before the show, Clarke saw Rolls in a hangar in Wolverhampton and spoke to him as he worked on his aeroplane with a spanner.

‘Making all tight?’ Clarke asked him.

‘Yes. Never take any risks that I can help. Would you?’

While careful preparation could minimise the risks, it could not eliminate them and Clarke would have known that all the pilots taking part in the Bournemouth air show were risking their lives in doing so.

One of the displays at the air show saw pilots compete against each other by trying to land their aeroplanes nearest to a given spot. On his first attempt Rolls landed 20 feet from the target, beating an effort by Claude Grahame-White by 10 feet. But rather than wait to see if this was enough to give him victory, Rolls decided to try to get closer still.

His second attempt began normally but started to go wrong when one of the bars of his aeroplane buckled as he lifted it to clear some railings. Clarke wrote in the Manchester Guardian:

His machine rose nevertheless and cleared the fencing. With its upward momentum too it rose on the apex of its curve. But the collapse of the hinder plane had destroyed the whole balance of the machine. Its weight was thrown all to one end. You might compare it almost to a seesaw when the boy at one end has fallen off. Instead of completing the curve through the air with a glide to earth the machine reached the apex of the curve only, and then, after an instant’s dead pause, turned tail up and fell sheer down, Rolls on the front of it.

Rolls landed clear of his aeroplane and Clarke was one of a group of people who joined hands to form a circle around him to stop the crowd that swarmed forward. The line of arms was broken to let stretcher-bearers through, and as they lifted Rolls onto the stretcher Clarke noticed a man holding a camera.

‘With cold deliberation he pointed it at the brown stretcher sheet,’ Clarke wrote. ‘A fist dashed it from his grasp, and an angry heel crushed through screen and plates.’

Rolls was carried away but he was already dead. He had become the first British fatality in an aeroplane accident. In itself, this was a tragic landmark in the history of British aviation. Combined with Rolls’s celebrity, it meant Clarke had witnessed one of the biggest stories of the age unfold in front of him.

In the Manchester Guardian the following day, Clarke began his article with the understated power characteristic of the best news reporting:

Mr C.S. Rolls, one of the two or three most capable and distinguished of British flying men, met with his death on the aviation ground here this afternoon.

His aeroplane broke, and fell some thirty feet straight down, he with it, and the fall killed him instantly. He dropped clear of his machine and lay still on the turf on his back, his neck broken. It was a terrible sight.

Clarke’s article went on to describe his impressions of the tragedy:

One cannot forget the sounds of that accident. First the crackling of the rear plane as it broke. It was like that of a fire of damp sticks. Then the grinding of wood and iron, the dull pizzicatos of snapping wires, and their whirring hiss as they curled up like watch-springs.

Then that tense moment of stillness, more terrible than noise, when the biplane lay poised in the air deciding whether to fall tail first or head. The head had it. The planes turned slowly from horizontal to vertical; then down came the whole thing, thud on the grass … Tail and head, skids, sides, engine, and all lay in one low heap of wreckage, with Rolls beside it, his face to the sky, a hand palm upwards on his chest.18

It was a powerful piece of journalism, and when he left the Manchester Guardian it was this article that C.P. Scott mentioned when he said some kind parting words to him.19

***

Witnessing Rolls’s death did not diminish Clarke’s interest in flying, and soon afterwards he even played his own small role in aviation history when the actor and aviator Robert Loraine invited him to travel with his mechanics in the support car that helped him prepare for the first ever flight over the Irish sea.20

Then just a month later he was given the chance to experience flight for himself when Claude Grahame-White, one of the pilots Rolls had been competing against when he died, offered to take him up in his Farman biplane.

Clarke accepted the offer but as he walked onto the airfield near Blackpool he noticed the wreck of an aeroplane lying 100 yards away. It brought back images of ‘Rolls quiet on the grass’, which he later recalled was not the ‘most comfortable prelude to a first essay in flight’.

When he reached the aeroplane, he found Grahame-White already inside, looking up at the sky.

‘Bit windy, don’t you think?’ Grahame-White said. ‘Suppose I just try first by myself and see what it’s like, you don’t mind?’

‘Just as you think,’ said Clarke, trying his best to sound relaxed as he felt the strong wind against him and imagined how much more powerful it would be high above the ground.

‘Very well, then,’ said Grahame-White, impressed by what he thought was Clarke’s nonchalance. ‘Clamber up behind.’

Clarke climbed over Grahame-White’s shoulder and sat behind him, where he took comfort from the illusion of control he felt at being able to see what his pilot’s hands were doing.

‘Quite comfy?’ a man on the ground shouted at Clarke above the noise of the propellers.

Clarke made an affirmative gesture and the man signalled to four other men who were holding the back of the aeroplane. They released their grips and Clarke felt it begin to move forward. It rattled at first, but as they continued the rattling became steadily quieter until Clarke looked over the side and suddenly realised they were high above the ground. He wrote:

At what point we left it I could not say, for I had felt no sudden heave upwards, such as an aeroplane seems to make in rising when seen from below. We were in the air. Yet nothing had altered. But for the fact that the wind was whistling past my ears and that the sound of the engine seemed much more remote than it had been, there was nothing much to show that we were not still standing on the ground with the engine running. I found, however, on watching an earth-object for a moment, that we were rising at one steady angle. Yet so still and comfortable were things that the extraordinary fierceness of the wind seemed out of place. It was like having your head out of an express train window. It went like a brush over your head (I was without a hat), and forced a way like something solid into your mouth did you happen to open it ever so little.

They had been flying for a few minutes when the aeroplane tilted ominously and suddenly lost altitude. Grahame-White did not seem especially worried but was unhappy enough with the aeroplane’s performance to take it back in to land.

‘She’s not pulling well,’ he shouted to his mechanics when they were back on the ground. ‘Just have a look what’s up.’

Grahame-White climbed out and he and the crew worked on the aeroplane for about a minute. Then when he was satisfied he climbed back into the pilot’s seat and they were soon back in the air.

‘By this time I had become more used to the inner life of the aeroplane and was able to take fuller notice of things further afield, of the crowds below, of the country and sea outside the aerodrome, my range growing ever wider as we mounted,’ Clarke wrote. ‘And I don’t remember having the slightest concern as to the machine and its safety.’

As they flew over farms and fields, Clarke looked down on the earth below and in the article he tried to describe a feeling that had then only been experienced by a handful of people:

It is not in the distant prospect that lies the uniqueness of a flying machine as a view point. Were this all, a peep from a tower top would serve almost as well. It is the addition of motion to your height that makes your view point the rare thing it is.

And it is in the nearer rather than the remoter prospect that the strangeness of this view is to be noticed most. There was something very extraordinary, for instance, in watching a forty-foot pylon, with flag at its peak, gradually foreshorten and foreshorten till eventually, as we passed high over the top of it, it was nothing but a little white square with a red streak across it. In the same way a man of the crowd gradually dwarfed down till he became a pair of shoulders with an upturned face inset between them; a woman till she became just a black circle – a hat.

When it was time to land, Grahame-White turned off the engine and pointed the aeroplane downwards. They descended alarmingly quickly until they were only about 50 feet from the ground and then the aeroplane suddenly levelled off and they safely eased towards the ground.21

Looking back on his career towards the end of his life, Clarke would describe his three years as a reporter for the Manchester Guardian as ‘the happiest of my journalistic life’. ‘One was on tiptoes all the time, it is true,’ he wrote, ‘but surely it is the on-tiptoes moments of life and work that are the most worthwhile, memorable and pleasant.’ Above all, he enjoyed working for a newspaper his fellow reporters were so passionate about, writing that ‘no gathering of womenfolk ever discussed hats and fashions with more earnestness and zest than we of the M.G. Reporters’ room discussed that mornings paper and one’s own and one’s colleagues contributions to it’.22

So when he was sounded out for a job with the Daily Mail in 1910, he was not particularly interested and responded with a salary demand he assumed would be prohibitively large.23 But to his surprise, the Daily Mail agreed to pay him close to what he had asked for, along with the promise that he would never have to write anything that went against his political beliefs.24

Clarke accepted the offer. When he wrote to C.P. Scott to give his notice, he told him that ‘if I am to do as well for my own kiddies as I was done by I must earn more money during the next 10 years or so’.25 It was true that Clarke was now thirty and had four children to care for – Alice had given birth to another boy, who they called George, in 1908 – but he later admitted that ‘it was not that I greatly needed more money and was short of it, or that I liked money unduly for its own sake’. Yet it was purely the prospect of extra money that made him leave the Manchester Guardian. Later in life, he wrote that he found it difficult ‘to realise why that constituted an adequate inducement – a sufficient lure and bait to attract me from what I was fully conscious at the time was more of a primrose path than a “job of work”’.

As well as his sadness at leaving his beloved Manchester Guardian, he also felt trepidation at moving to the Daily Mail, which he regarded as ‘more commercial and mundane in its editorial outlook’26 and which had a reputation among journalists for ‘not being too nice in its treatment of its staff’. But as brash and aggressive as the Daily Mail may have been in its editorial style, it was also phenomenally successful. He must have known that if he could meet the demanding expectations of his new job, it had the potential to take him to the very summit of British journalism.

Notes

1 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/2, Testimonial from Herbert Sidebotham to Clarke.

2 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, pp.65–6.

3Manchester Guardian, 9 March 1906, p.12 (Clarke made it clear in his Unfinished Autobiography that he was the author).

4 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/6, letter from Clarke to C.P. Scott, 19 April 1907. In his Unfinished Autobiography, Clarke wrote that C.P. Scott asked him to apply for the job after being impressed by his occasional articles. But there is nothing that suggests this from Clarke’s application letter, and it is likely that, looking back at least thirty years later, Clarke misremembered what had happened.

5 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, p.72.

6 Manchester University: John Rylands Library 127/84, letter from Clarke to C.P. Scott, 21 April 1907.

7 Tom Clarke, Northcliffe in History, An Intimate Study of Press Power, London, 1950, p.165.

8Manchester Guardian, 21 March 1910, p.16 (Clarke makes it clear in his Unfinished Autobiography that he wrote this article).

9 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, p.85.

10The Practice of Journalism, Ed. John Dodge and George Viner, London, 1963, p.60. The reference to Clarke’s interview with Rutherford was in a chapter entitled ‘A Reporter’s Memoir’, by Maurice Fagence.

11 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/9, Memo from William Percival Crozier to C.P. Scott, 15 October 1916.

12 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, pp.74–5.

13 Sir Basil Clarke, A Reporter’s Memories of Lloyd George, The Journal, Institute of Journalists, May 1945, p.62.

14 Basil Clarke, My Round of the War, London 1917, p.82. In Clarke’s account the words ‘head off’ were preceded by a blank, to indicate a swear word without actually stating what this was. But he uses the word ‘bloody’ when relating the same story in his Unfinished Autobiography.

15 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, pp.78–9.

16Manchester Guardian, 20 October 1909, p.7. The article is not by-lined, but his colleague at the Daily Mail, Tom Clarke, made it clear that Clarke was the author (Northcliffe in History, An Intimate Study of Press Power, London, 1950, p.165).

17 Tom Clarke, Northcliffe in History, An Intimate Study of Press Power, London, 1950, p.165

18Manchester Guardian, 13 July 1910, p.7. The article is not by-lined, but in a letter to C.P. Scott some years after he left the Manchester Guardian, Clarke reminds him about kind remarks Scott had made about Clarke’s coverage of the tragedy.

19 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/8, Letter from Clarke to C.P. Scott, 11 October 1916.

20 Basil Clarke, Unifnished Autobiography, pp.86–7.

21Manchester Guardian, 16 August 1910, p.7.

22 Basil Clarke, Unfinished Autobiography, p.83.

23 Ibid.

24 NUT, Schoolmaster, 10 October 1935.

25 Manchester University: John Rylands Library, A/C55/7a, Letter from Clarke to C.P. Scott, 26 October 1910.

26Daily Sketch, 20 March 1940, p.10