Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

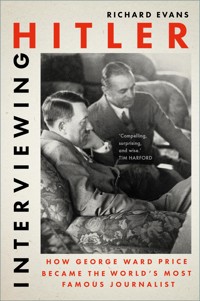

George Ward Price rose to prominence as the leading journalist in the 1930s, thanks to a string of world exclusives on Nazi Germany. He spent an hour alone with Hitler and Göring after the remilitarisation of the Rhineland, stood next to Hitler as he addressed a crowd on the night of the invasion of Austria, and joined him for afternoon tea at the Eagle's Nest following his historic first meeting with Neville Chamberlain. These stories made Ward Price world famous, but he often seemed uncomfortable in the glare of the spotlight, hiding his true self behind a carefully cultivated veneer of suave and easy-going charm. It meant that he left unanswered questions: what drove his all-consuming ambition? Was his success down to journalist brilliance, or was there something more sinister that lay behind it? And were there any lengths to which he would not go to make sure that, as one of his colleagues put it, he 'always got his story'? Interviewing Hitler is the first book to explore the real Ward Price and the truth behind his reporting on the Nazis. It is a journey that takes us through a series of century-shaping events and deep into the dark heart of British journalism. As well as being one of the most controversial figures in newspaper history, Ward Price's career serves as a warning for today's world of disinformation and fake news.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 371

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Richard Evans, 2025

The right of Richard Evans to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 914 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

For Norman Ebbutt, John Segrue,and all the ones who tried to warn us.

Contents

Introduction

PART ONE

1 On the Balcony at Linz

2 ‘Always there’

3 ‘Monocled Prince of the Press’

4 Linz and Vienna

5 Chronicler of the World

PART TWO

6 Berchtesgaden

7 Bad Godesberg and Munich

8 ‘I congratulate you very heartily’

9 Devil’s Advocate

10 Being Close to the Story

11 With Rothermere

PART THREE

12 ‘Towards war’

13 Against Hitler

14 With Hitler?

15 With Churchill at Casablanca

16 After Hitler

17 Extra-Special Correspondent

Epilogue: With Unity and Franco

Acknowledgements

Notes

Further Reading

Select Bibliography

Introduction

The idea for this book came to me after I came across an old copy for sale of George Ward Price’s autobiography, Extra-Special Correspondent. I had long been interested in newspaper history and so had already heard of Ward Price, his name having been mentioned here and there in books I had read about journalism in the first half of the twentieth century and international politics of the 1930s.

As much as I knew anything about him, it was that his interviews with Adolf Hitler, at key moments of international tension, had been some of the biggest newspaper exclusives of the time. Yet I also had the impression that these were successes that somehow carried a taint, with a sense of suspicion about how he had gone about them, meaning historians were more likely to sneer at them than celebrate them.

One of the reasons I became interested in journalism history is the moral ambiguity at the heart of the profession, and because of how newspaper articles contain implicit choices that sometimes reveal as much about the character of the journalists writing them as they do about the people or events they are about. Probably my favourite book about journalism is The Journalist and the Murderer by Janet Malcolm. It tells the true story of Joe McGinniss, an American journalist who wrote a book about Jeffrey MacDonald, a convicted murderer who maintained that he was innocent. McGinniss did not believe him, yet he understood that being able to write the book depended on him having access to him. This, in turn, depended on MacDonald thinking McGinniss was on his side. So McGinniss allowed him to believe. Through telling the story of McGinniss and MacDonald, The Journalist and the Murderer explores the compromises, big and small, journalists make as a part of their job.

As I looked at the old copy of Extra-Special Correspondent, I found myself wondering what kind of compromises Ward Price might have made. Because while The Journalist and the Murderer brilliantly sets out the ethical dilemmas and compromises inherent in journalism, it does so on a relatively small scale. It concerns itself with the reporting of a moderately big story about a single criminal convicted of murdering three people. But what kind of compromises, I wondered, would it have taken to get the inside track on perhaps the biggest story of the century, where the driving force behind that story was a man so monstrous he has become, in all our minds, a cypher for evil?

With the vague sense that Ward Price’s reporting on the Nazis had attracted as much criticism as praise, I was curious to know how, writing in the twilight of his life, he might have responded to his critics. Would he defend himself, or would he regret compromises made in the pursuit of ambition? Perhaps the book contained answers to the kind of questions Malcolm raises in The Journalist and the Murder. So I decided to buy it.

As I turned its yellowing pages, I was surprised to learn that, in writing the story of his career, Ward Price had chosen to neither deny nor accept the criticism of his reporting. He does not even mention it. Whatever he may have thought in the 1930s, by the time he came to write the book in the 1950s, his attitude towards Hitler and the Italian fascist Benito Mussolini was aligned entirely with the accepted view of the age. ‘Hitler and Mussolini will stand out as two of the most pernicious and powerful influences that have ever been exerted upon human affairs,’ Ward Price wrote, going on to add that they had ‘allowed their reckless ambition to plunge them into evil enterprises which brought incalculable misery upon their own people and to a great part of the rest of humanity’.1

Yet despite its unequivocal condemnation of Hitler and Mussolini and his decision not to mention his criticism, there is a sense that this criticism hangs over his writing like a ghost. At one point, he even launches into the kind of robust defence of his reporting that would have been unnecessary if there had been no criticism to respond to.

In reporting on Hitler and Mussolini, Ward Price insists, he had been both doing his job and serving the public interest: ‘The course I always took with the Dictators was to repeat the criticism aroused in Britain by their regimes. The statements made to me by both Dictators thus provided British newspaper readers with an opportunity to form their own estimate of the genuineness or falseness of the declarations that they made.’2 ‘I reported his [Hitler’s] statements accurately,’ he explains, ‘leaving British newspaper-readers to form their own opinion of their worth’.3

Far from admiring Hitler, Ward Price goes on, he had never been able to understand how someone of such limited ability had got such a hold over the German people: ‘The many meetings that I had with Hitler, both on public and private occasions, always filled me with astonishment that a man of his neurotic character and limited perceptions should be able to maintain personal domination over a race possessing such varied and conspicuous qualities as the Germans. Though his flamboyant speeches and melodramatic parades might intoxicate the lower grades of the German people, it was surprising to see the deference displayed towards him by so many Germans who were his superiors in education, intellect, and experience.’4

He then mentions that his own name had been included in a Nazi ‘Black Book’ of prominent Britons to be arrested following an invasion of Britain. How could he have been a Nazi apologist, he seems to be saying, when the Nazis had been planning to arrest him?5

From reading Extra-Special Correspondent, it was clear that one of two things must be true. Either Ward Price’s critics had unfairly maligned him, perhaps driven by jealousy of his astonishing success, or his autobiography presents a deeply misleading account of how he had covered the Nazis. But I also knew that, whatever Ward Price and critics might have written years later, the truth of how he had reported on the Nazis would be there to be found in what he had written at the time. And so I began to look. It was the start of a journey that would take me deep into the dark heart of British journalism in the 1930s, and this book is the story of that journey. In the following pages, I will tell the story of how Ward Price reported on the Nazis, and also try to peel back the layers of the personality of one of the strangest, most enigmatic figures in newspaper history.

To tell Ward Price’s story is also to tell part of the story of the Nazis. Following him into rooms with Hitler, Göring, Ribbentrop and the rest of them may not offer an in any way comprehensive view of how they plunged the world into war, but the fragmentary snapshots it offers are, in their own way, illuminating.

There are two things, in particular, that I have taken from reading the accounts of Ward Price’s meetings with the Nazi leaders. Firstly, I had always assumed that you would have had to be wilfully ignorant or obtuse to have even considered believing Hitler’s assurances about not wanting war. For one thing, believing in his commitment to peace would be to ignore what he himself had written in the 1920s. Yet, as I read the apparent earnestness with which he told Ward Price about how his experience in the First World War had made him determined not to see another generation of young German men cut down, I thought again. Perhaps I would not have seen through Hitler’s lies quite as easily as I had always thought.

Secondly, the parts of the conversations between Ward Price and the Nazi leaders that I found most unsettling were not the discussions of policy, even when they descended into crude racial hatred. More disturbing were the informal moments, of Hitler making a humorous comment or Göring playing affectionately with his young daughter. Because while I already knew quite a lot about the Nazis after learning about them at school and university and watching various films and documentaries, I realise now that I had come to think of the Nazi leaders as symbols of evil rather than real people who were made of flesh and blood. As the accounts of their conversations with Ward Price gave me glimpses of their humanity, it made the mass murder they perpetrated seem all the more disturbing and unfathomable.

PART ONE

1

On the Balcony at Linz

Linz, Austria; 12 March 1938. Night has fallen and Adolf Hitler is standing in the cold on the balcony of the city hall, looking out at buildings festooned with swastikas and a crowd of thousands of people who are looking up at him and chanting in unison: ‘One leader; one people; one state.’

To Hitler, it must have seemed the culmination of a series of triumphs that had first taken him from obscurity to become the all-powerful ruler of Germany, and then transformed Germany itself from a weak and unconfident country into one feared across Europe.

The Wehrmacht had crossed into Austria earlier that day, marking the first time Nazi Germany had invaded another country. It had gone better than Hitler could have dared hope, the Austrian army putting up no resistance at all, and thousands of ecstatic Austrians lining the streets to welcome their invaders. Hitler himself crossed the border a few hours later, visiting his birthplace of Braunau am Inn, and then driving on through streets filled with delirious crowds to Linz, where he had spent much of his childhood.

And now, the crowd in Linz was looking up at Hitler not as a conqueror but as a lost son returned home to deliver them to a greater future. The almost religious fervour of their chanting must have seemed to confirm everything he had long believed about himself as a man of destiny.

But it was not just Hitler who must have thought this moment represented the high point of a brilliant career. Standing alongside him was a tall Englishman with slicked-back hair and a long scar on his forehead, whose very presence on the balcony seemed the final proof of his position as the world’s greatest journalist.

George Ward Price was 52 years old and worked for the Daily Mail. He had flown into Austria the previous afternoon, as its government’s attempt to undermine Germany’s aim of bringing Austria into its orbit by holding a referendum on Austrian independence seemed likely to bring tensions to boiling point. Ward Price had arrived to find Vienna in what he called ‘a state of supreme excitement such as has rarely prevailed in Europe since the Great War’. Most shops were closed, Austrian troops were stationed around the capital to maintain order, and rumours swirled that the referendum had been cancelled and Germany was about to invade. Ward Price drove to the Chancellery to try to get official news, and he arrived there to find ‘an odd air of suspended animation’. He walked past guards with machine guns and, inside the building, he met Ludwig Kleinwächter, the head of the government press bureau.

‘I think there are good grounds to believe that the plebiscite will be postponed,’ Kleinwächter told him, smiling grimly.

‘What has happened?’

‘Strong objections to it have been put forward by the German government,’ said Kleinwächter, looking uneasy. ‘I may be able to tell you more if you ring up in an hour or two. All I know is that the cabinet is now sitting, and that information has been received that three German Army Corps are concentrated on the Austrian frontier.’

Ward Price left the Chancellery and drove to the luxurious Hotel Bristol, where he had been a regular guest since before the First World War. It was now early evening, and large crowds had gathered in the streets. By the time he reached the hotel, the Austrian government had already announced the referendum had been cancelled, and Ward Price telephoned Kleinwächter to ask for an update.

‘We have just heard that the German troops will cross our frontier within the next hour,’ said Kleinwächter, his voice trembling. ‘It is being given out in Germany that in Austria everyone is fighting everyone else, and that a regular bloodbath is going on here.’

Ward Price began firing questions at him, but Kleinwächter cut him off. ‘I know nothing more, and I doubt I shall be able to tell you anything else. I may not be here for much longer.’ Kleinwächter was right. He would be arrested a few hours later and eventually sent to Dachau concentration camp.1

As Ward Price put the telephone down, the hotel manager called him over to the radio, telling him that Austrian Prime Minister Kurt Schuschnigg was making an announcement. Ward Price listened to Schuschnigg announce he was stepping down as prime minister in the face of German demands, and that, to avoid bloodshed, he had ordered the Austrian army to fall back if the German army crossed the border. When Schuschnigg finished speaking, Ward Price went out into the streets, where people had been listening to the speech over loudspeakers. At first, there was a sense of hush as people absorbed the news. Then he heard a chant, quiet at first, but then louder and louder as more people took it up, of the Nazi ‘Sieg Heil’. Ward Price started walking and, before long, it seemed to him that ‘the whole city was chanting it now’. Suddenly, swastikas were being put on display all around him, and he saw lorries driving past filled with rifle-carrying men wearing swastika armbands. Large numbers of Nazis began marching through the streets, and Ward Price saw a symbolism in the way they trampled over the leaflets littering the pavements that urged people to vote for Schuschnigg in the now cancelled referendum.2

‘Tonight Vienna is entirely in the hands of triumphant, cheering, flag-waving, torch-bearing Nazi demonstrators,’ he wrote in his report for the next day’s Daily Mail. ‘Police lorries are already flying the Swastika pennant, while girls are pinning Swastika armbands on the sleeves of policemen. Another chapter of history is closing tonight. Once mighty Austria is becoming another province of Nazi Germany.’3

He now needed to send his article to London; he arrived at the telegraph office to find its large and dingy room filled with journalists. Some were German Jews who had moved to Vienna to seek refuge from the Nazis and now faced falling under their control again. As Ward Price waited to send his article, a group of rifle-carrying young Nazis entered the room. Their leader announced their arrival by hitting the butt of his rifle against the floor, while the others pointed their guns at the journalists.

‘Nobody is allowed out!’ shouted the leader.

Ward Price was surprised by the journalists’ lack of reaction, as they ignored the armed men and calmly continued writing. Then a postal official approached the Nazi leader and politely told him that the journalists were busy writing articles, and that their presence was disturbing them.

‘But they must not send any!’ snapped the Nazi. ‘I am here to prevent that!’

The official replied that he would not be able to close the telegraph office without a written order from the government, and the two men began negotiating a compromise whereby the journalists would be allowed to send their messages as long as they were first checked by the Nazis. While this was going on, Ward Price managed to slip out of the room unnoticed, going to the Marconi wireless office around the corner, from where he was able to send his article in peace.

Ward Price then stayed up till 4 o’clock, watching Nazi supporters march through the streets. He noted how many of them were Austrian police officers who just a few hours before had been responsible for upholding the ban on any display of support for the Nazis. By the time he returned to his hotel, a large Nazi banner was hanging from its top windows.

After a few hours’ sleep, he was woken at 8 o’clock by the sound of aeroplanes. He looked out and saw the sky was filled with low-flying bombers dropping Nazi propaganda onto the streets below. Half an hour later, he drove through eerily quiet streets to the Chancellery, where he was surprised to find the sentry there greet him by removing his cap and bowing. He was directed into the building and up a curving staircase. At the top, two more sentries opened a gold door and ushered him into a room, where officials got to their feet and saluted him. As he introduced himself and asked for an audience with the new chancellor, the Austrian Nazi Arthur Seyss-Inquart, he had the awkward realisation that the officials had assumed he was a member of the new government.

Seyss-Inquart agreed to talk to him for a few minutes, and Ward Price asked him what was happening. Seyss-Inquart said the previous government’s decision to hold a referendum had breached an agreement between Austria and Germany, and so Austria’s president, Wilhelm Miklas, had asked Seyss-Inquart to form a new government that would meet Austria’s obligations. Seyss-Inquart said he had received reports that the German army had crossed the border earlier that morning, but that Austria would remain independent, though ‘fully conscious of her unity with the German race’. Schuschnigg, he added, was now confined to his house for his own safety.

After the interview, Ward Price drove to Schuschnigg’s house, where he found armed police guarding the entrance gate and a group of Nazi stormtroopers loitering nearby. Ward Price approached one of the police officers and confidently told him he was there to see Schuschnigg. But one of the stormtroopers overheard him.

‘No one can visit Dr Schuschnigg,’ the stormtrooper interrupted. ‘He is a prisoner, and not allowed to have communication with anyone.’

Ward Price had previously interviewed Schuschnigg, and he explained that he knew him and wanted to see for himself that he had not been harmed.

‘We are here to prevent that,’ said the police officer, ‘and he has a military guard inside as well.’

His powers of persuasion having failed him, Ward Price returned to his car without seeing Schuschnigg. It would be seven years, and take the fall of the Nazis, for Schuschnigg to finally be released.

Ward Price then drove through Vienna’s streets, watching people wearing swastikas greeting each other with ‘Heil Hitler!’, and seeing Jewish shopkeepers standing outside their shops, anxiously looking around at how dramatically their city had changed in just a few short hours. Ward Price guessed they were trying to decide whether to stay and hope for the best, or to abandon their businesses and flee.

At noon, he went to the telegraph office, where he listened to a broadcast by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, who announced German troops were crossing the border with the aim of ensuring the Austrian people could decide their own fate through a ‘real plebiscite’. Goebbels also said Hitler had left Berlin and was heading for the border. Ward Price thought Hitler was unlikely to actually enter Austria, but he wanted to make sure he was there if he did. So he hired a chauffeur and car and, after managing to get through a checkpoint on the outskirts of Vienna manned by white-shirted Nazis armed with rifles, they headed west in the direction of the German border. They drove for about 100 miles, passing lorryloads of Austrian soldiers heading in the opposite direction, many of their vehicles adorned with swastikas. Eventually, they reached the town of Enns, where they came across an advance party of German soldiers parked by the roadside. Ward Price told his chauffeur to stop, and he got out to talk to some of the soldiers. One of them mentioned they had heard that Hitler would soon be arriving in Linz. Ward Price suddenly realised he might be on the brink of a huge exclusive, and he hurriedly got back in his car and told the chauffeur to drive on to Linz.

After a short drive, they reached Linz to find its square crowded with people, swastikas displayed on the houses and German planes flying in formation overhead. It seemed that Hitler was expected to speak from the balcony of the city hall, so Ward Price left the chauffeur with the car and made his way to the entrance. The Nazi officials there refused to let him in, but this time he was determined not to take no for an answer. Over several tense minutes, he argued with them, using a mixture of bullying and charm as he insisted again and again that it was vital he was allowed inside. Eventually, someone in the building was found who knew who Ward Price was and so was able to vouch for him. Ward Price was brought up to the first-floor room that led out onto the balcony where Hitler was expected to address the crowd. The room was packed with local Nazis, and on a stretcher on a table was a Nazi who had been injured in a clash with the police. Ward Price went out onto the balcony and looked at the crowd below, and he noticed a group of Hitler Youth in short trousers who were cheering excitedly, despite being so cold the skin of their legs was tinged blue. As he looked beyond them, he saw that every window and rooftop was crammed with people.

There was a palpable sense of anticipation in the crowd, and the arrival of a group of cars in the square was greeted by a huge roar, as people assumed Hitler must be in one of them. But the cars were actually carrying Seyss-Inquart and the SS leader Heinrich Himmler. Seyss-Inquart and Himmler were brought into the city hall, and Ward Price managed to speak to Himmler. On their previous meetings, Himmler had reminded Ward Price of a ‘severe school-master’, but his face now seemed to glow with boyish excitement at the Nazi triumph he was witnessing. ‘What a grand thing it is to see a people reunited,’ he said. ‘I have never been so much moved in my life.’

While they waited for Hitler, Ward Price mingled with the Austrian Nazis in the room, feeling cold even in his greatcoat as he answered their questions about how the British might react to the news. Two of the men in the room had been at school with Hitler, and he took the chance to take down their impressions of what he had been like as a boy. He also listened to Himmler give a short speech to the crowd from the balcony.

Finally, at about 8 o’clock, a group of military vehicles arrived in the square, prompting another huge roar from the crowd. Ward Price strained his eyes to see through the darkness, and he was able to make out the figure of Hitler, standing in the back of an open car, his face expressionless and his arm raised in salute. The car stopped and Hitler climbed down and made his way through the delirious crowd and into the city hall, and then up the stairs and into the room where Ward Price was waiting.

As Hitler walked in, he noticed Ward Price and greeted him with a smile. ‘Well, Ward Price,’ he said. ‘Always there!’4

2

‘Always there’

‘Always there.’ It is difficult to think of two words that better describe George Ward Price’s time reporting on Nazi Germany than the ones Hitler used to greet him in Linz on the night of the invasion of Austria. For the previous five years, Hitler and the Nazis had been the biggest news story in the world, and no journalist had been closer to that story than Ward Price.

It had started a few months after Hitler became chancellor in 1933. Ward Price visited Berlin that October, meeting Joseph Goebbels, who was at pains to assure him of Germany’s peaceful intentions. ‘There is no question in central Europe which would justify another war,’ he said, before going on to point to Germany’s offer of friendship to France as ‘evidence of the Nazi Party’s capacity to evolve’.1 Ward Price also interviewed the economic minister, Hjalmar Schacht, who told him ‘the national spirit of Germany is now magnificent … and that is entirely due to Adolf Hitler’.2

But the highlight of his visit was an interview with Hitler himself. Wearing a double-breasted suit with a Nazi badge in his buttonhole, Hitler strode vigorously around a room at the Reich Chancellery as he gave Ward Price what the Daily Mail called the ‘most detailed and direct definition of Germany’s attitude in international politics which he has ever made’. ‘Nobody here desires a repetition of war,’ Hitler told Ward Price. ‘Almost all we leaders of the National Socialist movement were actual combatants. I have yet to meet the combatant who desires a renewal of the horrors of those four and a half years … Our youth constitutes our sole hope for the future. Do you imagine that we are bringing it up only to be shot down on the battlefield?’3

Far from threatening world peace, he explained, in just a few short months he had secured internal peace and security in Germany, at the same time as making Germany a bulwark against communism in Europe. He reiterated what Goebbels had said about having no grievances against France, but added a note of warning that ‘we will put up with no more of this persistent discrimination against Germany’. ‘We are manly enough to recognise that when one has lost a war, whether one was responsible for it or not, one has to bear the consequences,’ he said, ‘[but] it is intolerable for us as a nation of 65 million that we should continually and repeatedly be dishonoured and humiliated.’4

Ward Price’s first interview with Hitler was a big story that was covered around the world.5 Then four months later, Ward Price followed it with interviewing Hitler again following political violence in Austria between the right-wing government and the socialist opposition. Ward Price waited in a dining room while the Nazi cabinet met next door, and he could hear Hitler’s voice through the wall. Then once the meeting was over, Hitler, this time in a khaki uniform with a swastika armband, came out and sat with him. Hitler’s desire for a union between Austria and Germany led many to suspect he was the hidden hand behind the political violence there, but he insisted that reports that the Nazis had anything to do with it were ‘entirely false’. In this, at least, he seems to have been telling the truth, but he was not about to pass up a chance to undermine the Austrian government.

Hitting the arm of his chair to emphasise his points, he condemned Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss’s brutal suppression of his opponents, which had included shelling a housing estate. ‘Everyone knows you can smash houses to bits by shell fire, but such practices will not convince an adversary; they will only embitter him,’ said Hitler, with an earnestness that would have raised the eyebrows of those who remembered the street violence that had accompanied the Nazis’ rise to power. ‘The only way to succeed in a revolution is to entice your opponents over by convincing them. That is what we have achieved in Germany. Herr Dollfuss, on the other hand, has been trying to carry out a coup d’état.’

The interview then moved on to more general ground. Hitler pointed to the non-aggression pact Germany had recently signed with Poland as yet more proof that he was genuine about wanting peace. ‘The two nations have come close together,’ he said, ‘and I sincerely hope that our new understanding will mean that Germany and Poland have definitely abandoned all idea of a resort to arms not for 10 years but forever.’ Ward Price then asked about the political opponents the Nazis had sent to concentration camps. ‘They have been given time to modify their views,’ Hitler replied, ‘and as soon as they are prepared to pledge themselves to abandon their hostile attitude, they will be released.’6 Ward Price also enquired about the fates of three Bulgarians still in prison despite having been acquitted of involvement in the Reichstag fire the previous year, and Hitler confirmed they would be released. When the three men were allowed to fly to Russia eleven days later, the Mail proudly reminded the world that it had been Ward Price who had extracted the promise from Hitler, seeing its fulfilment as proof that ‘Herr Hitler knows how to keep his word’.7

Five months after the interview, Dollfuss was shot dead in Vienna as part of an attempted Nazi coup. Ward Price rushed there to report on the aftermath of the coup attempt, and he attended the trials of two of Dollfuss’s assassins, Otto Planetta and Franz Holzweber. Then three hours after the guilty verdict was handed down, Ward Price watched them being hanged.8 He also attended Dollfuss’s funeral, writing that ‘never have I noticed so many members of the general public weeping so obviously and unaffectedly as was the case today’. There, he spoke to the temporary head of the Austrian government, Prince Starhemberg, who told him that ‘Austria will fight to the last gasp of her breath to maintain her freedom and independence absolutely unimpaired’.9 While in Austria, he also spoke to officials from Austria, Germany and France about the prospect for war, and reported that ‘all of them discussed that possibility with a sort of horrified fascination, like men standing on a sagging, shaky bridge above a terrible abyss’.

Around this time, Hitler was tightening his grip on power in Germany. At the end of June 1934, the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ saw the brutal extrajudicial killings of scores of people who represented a potential threat to him, including Ernst Röhm, the head of the Nazi paramilitary organisation the SA (Sturmabteilung), and former German Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher. Then the death of German President Paul von Hindenburg at the beginning of August removed the last check on Hitler’s authority. Hitler responded to Hindenburg’s death by declaring himself head of state and agreeing a change to the army’s loyalty oath so that soldiers now had to declare their allegiance to him personally.

Three days after Hindenburg’s death, Ward Price was in Hitler’s large new office in the Reich Chancellery for another interview. Hitler, wearing a mourning band over his red swastika armband, again promised that Germany’s foreign policy was driven only by a desire to protect itself, and that it would only ever fight in self-defence. ‘This country has a more profound impression than any other of the evil that war causes,’ he said. ‘Ninety-five percent of the members of the national administration have had personal experience of its horrors. They know that it is not a romantic adventure but a ghastly catastrophe. It is the disciplined conviction of the Nazi movement that war can benefit no one, but only bring general ruin in its train. To us, war would offer no prizes; 1918 was for us a lesson and warning. In our belief, Germany’s problems cannot be settled by war. Her claims from the rest of Europe involve no risk of such a disaster, for they are limited to what other nations regard as their most elementary rights. We ask only that our present frontiers shall be maintained.’

But what about interference in other countries’ politics, Ward Price asked. Had Germany not been accused of sowing discord in Austria? At this, Hitler’s voice suddenly became brusque and filled with irritation. ‘We cannot prevent Austrians from seeking to restore their ancient connection with Germany,’ he said. ‘These states are only separated by a line, on either side of which are people of the same race. If one part of England were artificially separated from the rest, who could restrain its inhabitants from wishing to be united to the rest of their country again?’ Perhaps realising he had said too much, he quickly added that ‘the question of the Anschluss [political union] is not a problem of the present day … we all know that this aim for the time being is impossible, for the opposition to it from the rest of Europe would be too great’.

Ward Price then raised the subject of the Night of the Long Knives. ‘The world was startled five weeks ago by evidence of divisions in the Nazi forces, and by the stern measures with which they were repaired,’ Ward Price said. ‘Are you satisfied now that the party is completely united?’ Hitler’s eyes flashed with anger at the question. ‘It is stronger and more solid than it ever was,’ he said, curtly.10

Just over two weeks after Hindenburg’s death, Hitler held a referendum to confirm his position as head of state. Widespread fraud and voter intimidation meant victory was inevitable, but the Nazis still campaigned feverishly for a yes vote, and Ward Price spent much of the campaign with Hitler as he travelled from southern Germany up to Hamburg. From there, Ward Price reported on how the Nazis had spent the campaign keeping ‘the whole country under a ceaseless drumfire of exhortation,’ with the result that ‘German idolisation of Adolf Hitler has reached its climax’. Nazi propaganda had been so ubiquitous during the previous week, he wrote, that newspapers had contained little else but appeals to vote for the Nazis, every street seemed plastered with Nazi posters, and city streets were filled with the ‘hoarse blare’ of speakers pumping out pro-Nazi speeches.11 It was no surprise when the Nazis won an overwhelming 90 per cent of votes cast.

Ward Price was also in Berlin at the end of 1934 to accompany Daily Mail owner Lord Rothermere when he was invited to dine with Hitler and some of the other leading Nazis. After dinner, they moved into a large room for a concert of German music, and Ward Price found a chair from which he could discreetly watch Hitler, hoping Hitler’s expression while he listened to the music might offer a clue to his private personality. At first, Hitler looked bored as he slumped in his seat, but when an opera singer began to perform a romantic song, his bearing suddenly changed. He smirked lecherously at the singer and as soon as she had finished he rushed over to her and repeatedly kissed her hand in what Ward Price called a ‘passionate, mumbling manner’. The next performer then began singing a martial song about a great cavalry leader, and Ward Price watched, fascinated, as Hitler’s demeanour changed again. Now, he pouted and thrust out his chest, sitting bolt upright and looking around the room with ‘flashing eyes’. Ward Price found the sudden changes in his mood disconcerting, and he wondered if his extreme reaction to the music came from the same place as his ability to work himself into a frenzy during his speeches.12

A few days later, Rothermere returned the invitation and hosted a dinner at the Adlon Hotel in Berlin for Hitler and a party of guests that included Goebbels, Air Minister Hermann Göring, Hitler’s confidant Joachim von Ribbentrop, and Ward Price. But this dinner did not go well. Hitler talked so incessantly that he did not touch his food, and then just as Rothermere stood up to make a speech, someone accidentally knocked over a vase. The SS guards waiting outside thought the sound of the vase smashing might be an assassination attempt, and burst into the room with their guns cocked. Hitler then left abruptly, and the meal ended without dessert.13

It was not just Hitler who Ward Price spent time with during the 1930s. He got to know Himmler and Goebbels, and had many meetings with Ribbentrop, particularly after Ribbentrop became German ambassador to the United Kingdom in 1936. But the Nazi he got on best with was Göring. The two men spent long hours together at Göring’s Carinhall hunting estate north-east of Berlin, discussing international politics. But Ward Price also got to know Göring as a person, being shown Göring’s vast model railway, watching him playing with his baby daughter and with the lion cub he kept as a pet, and listening to him and his wife discuss home improvements.14

During an interview in 1934, Göring strode up and down his library as he bemoaned how the Treaty of Versailles had left Germany virtually defenceless by not allowing it to have an air force. It meant, he said, that any other country ‘could destroy our population and ravage our territory without sending a single soldier across their frontiers’.15 In this, Göring was repeating the standard Nazi grievances about Versailles. But when Ward Price interviewed him about the same subject a year later, Göring was no longer prepared to play the part of powerless victim. Wearing a black silk shirt, he spoke with steely confidence as he confirmed for the first time that Germany was developing a ‘fighting air force’. Göring insisted an air force was a ‘vitally essential part of every national defence system’, and so Germany’s decision to breach Versailles by developing one should not be seen as an aggressive act. ‘It is the passionate conviction of the German Air Force that the Fatherland must be defended to the very last,’ he said, ‘but this Force is equally convinced that it will itself never be used to threaten the peace of other nations. No impartial and level-headed person can dispute the claim of Germany in her especially vulnerable position to have a sufficient number of aeroplanes to guarantee her absolute security.’16

This was a big and exclusive story. It was not the fact that Germany was developing an air force that was surprising – a 1933 Foreign Office memo had summarised the ‘mass of secret information’ on its development, and Winston Churchill had claimed that its development was well advanced.17 In writing about Ward Price’s exclusive, the journalist William Shirer wrote that Göring had only ‘told him officially what all the world knew’.18 But what was significant was that the Nazis now felt strong enough to admit it publicly.

In 1935, Ward Price was in the Saar region on Germany’s border with France to cover a referendum on whether, having been separated from Germany after the First World War, it should now rejoin it. He interviewed the leading Nazi in the Saar, Josef Bürckel, who assured him that ‘patriotic Jews’ in the Saar had nothing to fear from Germany, as ‘only those whose activities are anti-German have any cause for uneasiness’.19 Then following the overwhelming vote to rejoin Germany, Ward Price was in Saarbrücken, the Saar’s capital, to watch Hitler acclaimed by a crowd of thousands.

Two months later came the news that Germany was introducing compulsory military service. This sent a wave of alarm across Europe. Not only was it another breach of the Treaty of Versailles, but it cast serious doubt on the sincerity of Hitler’s commitment to peace. The day of the announcement, Ward Price travelled to Berlin to try to interview Hitler; he was told that Hitler was about to leave for Munich, but that Ward Price was welcome to join him for the flight. So as Hitler and eight of his staff boarded their plane, Ward Price took a seat alongside them.

As he had done after the dinner in Berlin, he used it as a chance to observe Hitler in his more private moments. Given how frenzied he often seemed in public, Ward Price thought it interesting that he only heard him speak once during the whole flight – when he asked the pilot, ‘How long to Munich?’. As they flew, Hitler sat eating some sandwiches and drinking a glass of mineral water. When he had finished his meal, he read some official papers and a copy of Völkischer Beobachter, the Nazi newspaper, and then stretched out his legs and fell asleep.

A large crowd was waiting for them at Munich, and they disembarked to the sound of a military band playing ‘Deutschland Uber Alles’ and Hitler inspected a long line of soldiers, who clicked their heels as he passed. They then drove in a procession of cars to the city centre for a ceremony to commemorate Germany’s war dead and, as Ward Price looked at the people they passed, he saw wild adoration on every face.

Later that evening, Ward Price interviewed Hitler in his living room at the Four Seasons Hotel, where he thought he seemed ‘vigorous and fuller in the face than when I last saw him,’ but ‘still hoarse and throaty’.

‘You should come oftener to Germany,’ Hitler said, as they shook hands. ‘You have seen with your own eyes the enthusiasm that the German people have displayed towards me.’

Just as Göring had done when telling him about the air force, Hitler took great pains to stress that the introduction of compulsory military service should not be seen as a sign that Germany was planning for war. ‘The German people wants no war,’ he said. ‘It wants to be peaceful and happy. It wants, above all, to be able to respect itself. Self-respect is what I have given to the German nation. They could not go on living under the humiliating depression of the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles … This is a great nation. It did not deserve the humiliations through which it has passed. Its heart is filled with joy because it has been released from them. But believe me, that joy implies no feeling of aggression towards any other Power and no possible increase in the danger of war.’20

Hitler said that Germany was ‘quite clear that a revision of the territorial dispositions of international treaties can never be effected by unilateral measures,’ and that he was still eager to negotiate agreements with Britain and France. He added that Germany would have been happy to limit its armed forces as part of an international disarmament agreement, but that it was ‘a monstrous and humiliating outrage’ for it to be kept weak while other countries were allowed to remain strong. ‘You can well realise, therefore, the proud happiness that the restoration of its honour has brought to the German nation,’ he said. ‘But should you ask anyone of these millions whether this has anything to do with war or peace, he would be utterly at a loss to know what you mean.’