Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

On 1 September 1909, American explorer Frederick Cook caused one of the biggest sensations in exploration history when, after a year with no word from him, news arrived that he had not only survived his Arctic expedition but had become the first person to ever reach the North Pole. Cook was instantly transformed into one of the heroes of the age. With his boat due to arrive in Copenhagen a few days later, journalists from across Europe scrambled to get there in time to meet him. One of them was Philip Gibbs, an obscure British reporter whose chance encounter in a Copenhagen café led to an exclusive interview with Cook before he reached land. But the interview left Gibbs doubting the explorer's story, and so he decided to gamble his career and credibility by making it clear he thought Cook was lying. And so began a frantic few days when Cook was showered with accolades while Gibbs tried to prove his claim was a fraud. The Explorer and the Journalist is the extraordinary story of a high-stakes confrontation from which only one of Gibbs and Cook would emerge with their reputation intact.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 355

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Evelyn and Orson

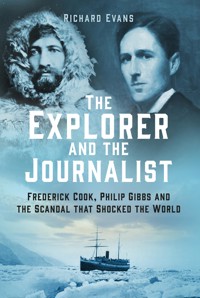

Front cover images, clockwise from top left: Frederick Cook (from The World’s Work, (New York: May 1909), p.565); Philip Gibbs (courtesy of the Gibbs family archive); steamship in ice (iStock.com/ilbusca).

Back cover image: Philip Gibbs interviews Frederick Cook on board the Hans Egede (courtesy of the Gibbs family archive).

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Richard Evans, 2023

The right of Richard Evans to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 194 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

1 A Spell Upon a Man

2 Among the World’s Great Men

3 Dr Cook, I Believe

4 The Story of the World

5 Going Right After Him

6 This Baffling Man

7 The Gravest Suspicion

8 Realm of Fairy Tales

9 The Most Amazing Man

10 I Show You My Hands

11 A Wild Dream

12 We Believe in You

13 His Own Foolish Acts

14 Setting Matters Right

15 Tides of Human Misery

16 The Psychological Enigma

17 The Wounded Soul

18 Epilogue

19 Endings

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Notes

1

A SPELL UPON A MAN

When Philip Gibbs arrived for work in the Daily Chronicle’s newsroom on the morning of Friday, 3 September 1909, he was called over by his news editor, Ernest Perris. As he walked to Perris’s desk, he had no idea the assignment waiting for him would change the course of his life and become a story told in the pubs of Fleet Street for generations of journalists to come.

Perris was an amateur boxer, a large man with big fists and a reputation for leaving sub-editors bloody nosed after sparring sessions. He was also one of the best news editors in Fleet Street, Gibbs describing him as ‘very human in quiet times, though utterly inhuman, or rather super-human, when there was a world scoop in progress’.1 But that morning, the Chronicle had already fallen behind its competitors in its reporting of one of the biggest news stories in years.

Two days earlier, on 1 September, the world had been stunned by the news that American explorer Frederick A. Cook had become the first person to reach the North Pole. This was the golden age of polar exploration, and all the world’s leading newspapers scrambled to send reporters to board boats and trains for Copenhagen, where Cook’s boat was expected to arrive. All the world’s leading newspapers, that is, except the Daily Chronicle. For reasons that have never been explained, a day and a half after the news had broken the paper had still not despatched a journalist to Copenhagen. But now it had changed its mind.

Perris told Gibbs to collect a bag of gold coins for expenses, take the razor and toothbrush he kept at the office, and leave for Copenhagen immediately.

‘Lots of other men have the start on you,’ said Perris, ‘but see if you can get some kind of story.’

Gibbs groaned. Going to Copenhagen would mean leaving his wife, Agnes, and their young son, Anthony, for who knows how many days. He also had no interest in polar exploration, knowing so little about it that he spent the boat journey repeating the name ‘Dr Cook’ to himself to make sure he remembered it, and thinking blackly that he would not even know what to ask Cook in the unlikely event that he managed to speak to him.

Perris probably chose Gibbs for the assignment because of his ability as a descriptive writer. Born in London in 1877, Gibbs had a passion for writing instilled in him at an early age by his father, a civil servant whose love of literature was so infectious that four of his nine children became novelists. Gibbs would always cherish childhood memories of his father reciting poetry to him as they walked down country lanes, and of dinners with him at the Whitefriars Club, where Gibbs met fascinating-seeming men who earned their living through writing.

Gibbs was 15 when he first thought that he, too, might be a professional writer, after something he had written was complimented by John Francis Bentley, the architect of Westminster Cathedral, whose children Gibbs was friends with.2 He had his first newspaper article published the following year, the Daily Chronicle paying him 7s 6d for a vignette describing seagulls screaming over London Bridge on a winter’s afternoon, and he followed this by writing some fairy tales that were published in Little Folks magazine. Then, after getting a job in the illustration department of a publishing company, he persuaded his employers to publish his first book, Founders of the Empire, which sold well and was used as a textbook in schools.

He was then appointed editor of a literary syndicate in Bolton, where he secured the rights and marketed the work of writers including Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling. While in Bolton, he also wrote a syndicated column that was published in newspapers across the country. The column was good enough to attract the attention of the Daily Mail’s brilliant but mercurial founder Alfred Harmsworth.

In 1902, Harmsworth invited Gibbs to London, and at the end of their meeting offered him a job as the Daily Mail’s literary editor. This marked the beginning of a career in Fleet Street that Gibbs soon found himself completely absorbed by. ‘Fleet Street puts a spell upon a man,’3 he wrote, describing it as ‘one of the best games in the world for any young man with quick eyes, a sense of humour, some touch of quality in his use of words, and curiosity in his soul for the truth and pageant of our human drama, provided he keeps his soul unsullied from the dirt’.4

But, as bewitching as he found what he called the ‘Spell of the Street’, the seven years he had spent in journalism by the time he came to report on the Frederick Cook story had been ones filled with false starts and disappointments, with all four of his previous jobs ending unhappily. His bad luck started on his very first day at the Daily Mail, when he arrived at the office – after uprooting his family from Bolton to London – only for Harmsworth to tell him he had forgotten offering him the job, and that he had instead appointed another journalist, Filson Young, as the Mail’s literary editor. There followed an awkward conversation where Gibbs reluctantly agreed to work as Young’s deputy.

Luckily, Gibbs and Young got on well enough to make the arrangement work and, when Young moved on, Gibbs was finally made literary editor. But his tenure did not last long. One day, Harmsworth invited him to lunch and told him he was secretly planning to launch a literary syndicate and he wanted Gibbs to run it for him. Harmsworth’s plan was for Gibbs to go back to the office that afternoon, announce he had been sacked, then go on holiday to the Riviera for a few months. By the time he got back, the syndicate would be ready.

Gibbs was shocked by the suddenness of the proposal and asked for a few days to think about it. But even as the words left his mouth, he saw Harmsworth’s face fill with disappointment.

‘You’re a cautious young man,’ Harmsworth said. Coming from someone who had become vastly wealthy through a series of bold decisions, it was not a compliment. Harmsworth immediately cooled on the idea, and shortly afterwards began criticising Gibbs’s work. Then, one day, Gibbs overheard one of the Mail’s editors criticise him to Harmsworth and saw Harmsworth respond with an ominous nod. Anxious to avoid the indignity of being sacked, Gibbs went upstairs and wrote a letter of resignation, giving it to a messenger boy to take downstairs. Half an hour later, a man arrived in his room and introduced himself to Gibbs as the new literary editor.

Suddenly out of work, Gibbs managed to get a job at the Daily Express, but this came to an end after he refused its owner’s instruction to write a series of articles proving Francis Bacon was the real author of what he termed ‘the so-called Shakespeare plays’. He then found a job at the Daily Chronicle, writing articles describing life in England and managing a team of three artists whose illustrations accompanied his descriptions. But he joined at a time when the Chronicle was starting to phase out using drawings in favour of photographs, and so it closed his department and made him redundant.

Undaunted, in 1906 he landed the job of literary editor at the Tribune, a new newspaper that was about to launch with a big budget and even bigger ambitions to transform British journalism. Gibbs’s own budget was so large that he was able to publish the work of writers of the calibre of Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad, and G.K. Chesterton. But for all its ambition, the Tribune was doomed from the start by the fact that its array of well-paid journalists was too expensive for it to have any realistic chance of ever breaking even, and the journalism they produced proved too highbrow for advertisers’ tastes. After month after month of haemorrhaging money, the owner pulled the plug and it closed in 1908.

On the evening it shut its doors for good, Gibbs stood outside the office with his friend Randal Charlton, sadly watching its green lights go out for the last time. Unemployed again, Gibbs decided to write a novel about Fleet Steet that would tell the story of a fictionalised Tribune, and have as its hero a character based on the foppish and unworldly Charlton. He rented a coastguard’s cottage in Littlehampton for a month, hoping it would give him the solitude to be able to focus on his writing. But he and Agnes arrived to find that it was next to a funfair, and so he spent his time there writing to the sound of a loud, blaring noise and children’s excited screams. Despite the noise, after a month of working late into the night he had produced a novel that he hoped had captured the chaos and exhilaration of life as a daily newspaper journalist in Edwardian Britain.

Now 32, Gibbs was trying to find a publisher for Street of Adventure when he got the chance to return to the Daily Chronicle, this time as a special correspondent. This meant he would now be focusing on news rather than the descriptive writing and literary criticism that had been his Fleet Street career so far. As well as lacking experience of writing news, there was good reason to think Gibbs’s temperament was unsuited to the tough and competitive world of news journalism.

A fellow journalist captured the essence of Gibbs’s personality when he wrote that ‘his broad brow, his pale, finely chiselled face, thin, sensitive lips, and big clear eyes, show something of the thinker, idealist, and poet that he is by nature’.5 G.K. Chesterton wrote that Gibbs’s ‘fine falcon face, with its almost unearthly refinement, seemed set in a sort of fastidious despair’.6 As a child, he had been so painfully shy that he had been unable to stop himself from blushing if someone used coarse language in his presence. He was also unusually sensitive – he would later remember lacking the ‘armour to protect myself against the brutalities, or even the unkindness, of the rough world about me’, and feeling the suffering of others so deeply that he would spend hours agonising over the fates of characters in novels.

So he hardly seemed a natural-born newshound, and his unsuitability seemed to be confirmed by his lack of the one quality every good reporter needs – a hunger for exclusive news. Gibbs even thought the chasing of exclusives was almost unseemly. ‘On the whole, I don’t much believe in the editor or reporter who sets his soul on “scoops”, because they create an unhealthy rivalry for sensation at any price – even that of the truth,’ he wrote, ‘and the “faker” generally triumphs over the truth-teller, until both he and the editor who encouraged him come a cropper by being found out.’7 In Street of Adventure, Gibbs seemed to acknowledge that this lack of hunger for news made him an unlikely news reporter. When the editor of the novel’s newspaper talks about what makes a good reporter, he dismisses the value of imagination and literary ability, instead imploring the gods of journalism to ‘bring me the man who can smell out facts’.8

As Gibbs sat on the boat carrying him towards Copenhagen and one of the biggest stories of the new century, there was nothing to indicate that he might be such a man. But if a journalist fails to seek out news, sometimes news comes to them unbidden. And so it was with Philip Gibbs.

2

AMONG THE WORLD’S GREAT MEN

From the vantage point of a time when mankind has stood on the Moon and launched probes that have sent back images from billions of miles away, it is difficult to grasp just how astonishing the idea of reaching the North Pole seemed to the world of 1909.

The North Pole had held a special place in our collective imagination for hundreds of years, and as the centuries passed and the globe slowly revealed its secrets, it was one of the few places that remained stubbornly unknowable. And the longer it stayed beyond humanity’s reach, the more humanity dreamed of the secrets it might hold. It was said to contain an abyss that ships could be pulled into, or iron mountains so magnetic that they could pull nails out of ships. Some even thought it might be a tropical paradise that was home to a lost civilisation.

It featured repeatedly in nineteenth-century literature – Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins’s play The Frozen Deep is set in the Arctic, and it is near the Pole that the doctor pursues the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Polar exploration also features in the work of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, Arthur Conan Doyle, Jules Verne, and many, many more.1

At the same time as writers were creating the North Pole of their imaginations, explorers were heading north to try to reach the real thing. The British explorer William Edward Parry set a new record for ‘farthest north’ in 1827, which stood for almost half a century before being beaten in 1876 by British naval officer Albert Markham, who got within 400 miles of the Pole, celebrating the achievement with whisky and cigars and the singing of ‘God Save the Queen’. Markham wrote that he had reached ‘a higher latitude, I predict, than will ever be attained’,2 but six years later his record was beaten by members of an expedition led by the American Adolphus Greely, though Greely’s expedition ended in tragedy as 18 of its 25 members died of starvation and some of the survivors resorted to cannibalism.3 The Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen made it even closer to the Pole in 1895, and in 1900 the Italian Umberto Cagni claimed the record by getting within 250 miles of it.

The exploits of Arctic explorers were followed avidly by the public, with books about their expeditions often becoming best-sellers. ‘There are no tales of risk and enterprise in which we English, men, women, and children, old and young, rich and poor, become interested so completely, as in the tales that come from the North Pole,’ the journalist Henry Morley wrote in 1853.4 Like the Moon landing many years later, the reason the public was so gripped by the idea of reaching the North Pole was not so much because of what might be found there, but because of what it seemed to say about the human spirit. And each expedition further added to the Pole’s mystique, the failures reinforcing its sense of danger and the successes increasing the public’s belief that the dream of reaching it might now be achievable. ‘May the day at least not be far off,’ wrote the Duke of Abruzzi, who had led the expedition on which Cagni had broken the record, ‘when the mystery of the Arctic regions shall be revealed, and the names of those who have sacrificed their lives to it shine with still greater glory’.5

Then, on 1 September 1909, a ship called the Hans Egede made an unscheduled stop at Lerwick in the Shetland Islands, and the ship’s officer rowed ashore with an American explorer called Frederick A. Cook. When they reached the shore, they walked to the town’s one-room telegraph station and sent five telegrams, all of them containing a single message – that mankind’s long, long quest to reach the North Pole was finally complete.

In newspaper offices around the world, shocked journalists sat down to write articles in which they tried to do justice to the magnitude of the news they were reporting. ‘It is difficult to find words adequate to express the stupendous significance of an event which ends a quest that has gone on steadily for so many scores of years and levied its toll on so many men,’ the Manchester Guardian reported. In France, Le Petit Parisien welcomed the ‘astounding news’ and Le Matin told its readers that ‘for the last five centuries the efforts of explorers have rushed to the arctic extremity of the world … and it is America which emerges triumphant in this heroic journey’.6

The London Daily News reported that ‘with intensely dramatic suddenness the report that an American, who had long been given up for dead, had reached the North Pole, burst on the world yesterday,’ while The Times thought that ‘if the story is confirmed, [Cook] will be enrolled among the world’s great men’.7The New York Times compared his achievement to Columbus’s ‘discovery’ of the Americas, arguing that ‘humanity would rank with that great voyager the man who shall have set foot on Earth’s chill and profitless extremity’.8 Philip Gibbs’s Daily Chronicle was just as effusive, declaring ‘all honour to the daring man who, having been given up for dead, has appeared with the news of victory’, and telling its readers that ‘it seems that what appeared to be the unattainable has been attained, and that, after a thousand years or more of perilous adventure, the Pole itself has at last been conquered!’9

Journalists also sought the reaction of the world’s leading explorers. The Duke of Abruzzi declared it ‘the greatest achievement of the twentieth century’,10 and Anthony Fiala, an American explorer who had spent two years stranded in the Arctic after his own failed polar attempt, said Cook ‘deserves immense credit for his brilliant success’.11 Cook’s friend Roald Amundsen, who would later become the first person to reach the South Pole, heaped praise on him. Cook was ‘an uncommonly staunch, persevering, and energetic personality, and I admire him’, Amundsen told journalists, adding that he thought his dash for the Pole was the ‘most brilliant sledge trip in the history of polar exploration’.

The Daily Mail got the explorer Ernest Shackleton, who had arrived back in London three months earlier after getting to within 112 miles of the South Pole, to write an article about Cook’s achievement. ‘Such a journey single-handed would seem to be an almost superhuman effort, and no praise would be too great for so fine a feat of courage and endurance,’ Shackleton wrote. ‘Dr Cook has succeeded, it seems, where many men have failed, and from the world at large, and from Polar explorers in particular, he will receive the warmest congratulations. I have very recent recollections of hardship and struggle in ice-bound regions, and therefore I can realise what the effort must have cost and feel personal pleasure that it should have been crowned with such magnificent success.’12

While explorers such as Shackleton, Amundsen, and Robert Falcon Scott were famous as a result of public fascination with the golden age of polar exploration, Cook had started the day hardly known outside the United States, most people being unaware of his expedition. So that afternoon, journalists also hurriedly researched the story of the man who had suddenly emerged from relative obscurity to claim a place alongside Marco Polo and Christopher Columbus in the pantheon of the very greatest explorers. From old newspaper cuttings and conversations with polar experts, they learned that Cook was a well-respected explorer who had quietly left the United States in June 1907 with a plan to reach the North Pole. He had hoped to be back by September 1908, but September 1908 had come and gone and, after no word from him for over a year, many assumed he was probably dead.

Many leading polar explorers came from relatively affluent families, but as journalists pieced together the details of Cook’s background, the picture that emerged of his early life was one of grinding poverty marked by a series of tragedies. The man who had been forged by this upbringing was one whose amiable and unassuming manner hid a resilience and will to succeed that was exceptional even by the extreme standards of polar exploration.

Born in 1865, two months after the end of the Civil War, Cook was the fourth of five children of German immigrants. He grew up in the foothills of New York’s Catskill Mountains, his first few years spent in relative comfort thanks to his father’s income as a doctor. But his father died when he was 5, and the loss of his salary meant the family’s existence was suddenly transformed into a constant struggle to find enough money to pay for food. The family then suffered further tragedy when Cook’s sister died of scarlet fever when he was about 15.

In his teenage years, Cook kept a punishing schedule of doing his schoolwork at the same time as holding down part-time jobs to support his family. By the time he left school at the age of 16, the family had moved to New York City and Cook got a job as an office boy and rent collector, saving his earnings until he could afford to buy a printing press, and using it to start a small printing business. He built up the business over the next few years and then sold it, using the money to buy a milk route that he hoped would give him a regular income while he went to medical school. So began an arduous routine of starting work on the milk route at 1 a.m., then going straight to medical school for 9 a.m., and then after a day’s studying going home to be in bed for 5.30 p.m., before starting the whole thing again. Not only did he manage to keep going, but he was able to grow the business and still found time to court Libby Forbes, a young woman he met at a temperance festival.

Cook and Libby married in the spring of 1889, and by the end of the year Libby was pregnant. To the 24-year-old Cook, it must have seemed that after his long years of struggle the pieces were finally falling into place for an idyllic life as a doctor with a loving family. But his life was shattered when their baby daughter died shortly after being born, and Libby died of an infection a week later.

Grief-stricken and suddenly alone, Cook threw himself into his work and, now newly qualified as a doctor, he sold the milk business and set up his own medical practice. But attracting patients proved harder than he expected, and the financial worry added to his grief. Around this time, he started reading books by Arctic explorers, finding escape from his sadness and anxiety in their stories of struggling to survive in an alien landscape. And then he read a newspaper article that was to change his life.

The article was about the American explorer Robert Peary, who was planning an expedition to Greenland and was looking for expedition members. Cook would later remember that as he read the article he had felt ‘as if a door to a prison cell opened’,13 and that same day he wrote to Peary to offer his services. Peary agreed to appoint him expedition physician, and Cook joined the expedition when it left New York in June 1891. They returned the following September with the triumphant news that they had significantly expanded human knowledge of the world by confirming for the first time that Greenland was an island.

Cook’s year in the Arctic had been filled with hardship. A member of the expedition was presumed to have fallen to his death after failing to return from collecting mineral samples, and Cook himself had only survived the collapse of an igloo he was sheltering in because Peary dug him out and then stopped him freezing to death by sheltering him from the wind. But the expedition had also showed Cook that he had a natural aptitude for polar conditions. He was so impervious to the cold that he sometimes chose to sleep outside in temperatures far below freezing, and he proved able to maintain his good humour even when the tempers of the other expedition members became badly frayed. He had also been fascinated by the Inuit they met in Greenland. While many nineteenth-century explorers had a racist attitude towards the Inuit that meant they dismissed them as inferior, Cook developed a deep respect for them and spent long hours studying their diet and customs and learning from them how to drive dogs and build igloos and sledges.

Above all, Cook’s time in Greenland had turned his interest in the Arctic into something closer to addiction; he would later write that ‘no explorer has ever returned [from the Arctic] who does not long for the remainder of his days to go back’.14 So when Peary announced his next expedition, Cook agreed to join him. But he withdrew after becoming annoyed with Peary for refusing to let him publish his research on the Inuit before Peary’s own book was published. Instead, Cook set off on his own trip to Greenland, and then the following year led an Arctic tourist expedition. But it was beset with problems from the start, and came to a premature end when it hit a reef and had to be rescued by another ship.

The publicity from Cook’s Arctic trips meant his medical practice was now doing well, and he again found personal happiness when he fell in love with and got engaged to his late wife’s sister, Anna. But he still felt the pull of exploration, spending the last few years of the nineteenth century unsuccessfully trying to raise the funds for his own Antarctic expedition. In 1897, he still had nowhere near enough money for an expedition when he read a newspaper article about the Belgica, a Belgian ship that was about to depart for Antarctica. As he had done with Peary six years earlier, Cook immediately wrote to the expedition leader, Adrien de Gerlache, offering his services as a doctor. De Gerlache initially rejected him, but when the Belgica’s physician resigned at the last minute, de Gerlache sent Cook another message offering him the role and telling him to meet them in Rio de Janeiro. By this point, Anna had fallen into ill health and Cook was reluctant to leave her, but the lure of exploration was too strong. He said goodbye to her and boarded a ship for Rio, where he met the Belgica and its crew of Belgians, Norwegians, a Pole, and a Romanian.

Among the crew was 25-year-old Norwegian Roald Amundsen, then unknown and inexperienced, but already ambitious and hungry to build the skills and knowledge that would lead to him becoming one of the world’s greatest explorers. Cook was the only member of the Belgica with previous experience of polar exploration, and so Amundsen was drawn to him as someone he could learn from. The two men developed a close friendship, Cook impressing Amundsen with a seemingly never-ending stream of ideas for the future that covered everything from designs for wind-resistant tents and snow goggles to introducing Antarctic animals to the Arctic and using penguin faeces as a fertiliser to solve world hunger.

They went hunting and exploring together, and their friendship was cemented by a dangerous trek they made when they were tied to each other with rope. Climbing a mountain, Amundsen was impressed by the way Cook calmly and methodically cut footholds in the ice despite being so high that any slip would mean falling to his certain death, and by the courage Cook showed in crawling across a sheet of ice that formed a bridge across a crevice, despite not being sure it would hold his weight. A little later, the snow gave way under Cook’s feet, and Amundsen had to use all his strength to pull the rope connecting them, so saving both of them from falling to their deaths. Cook returned the favour shortly afterwards when Amundsen suddenly fell through the snow and found himself dangling above a huge drop; Cook managed to hold onto the rope long enough for Amundsen to pull himself back up.15 Many years later, the lifelong bond between the two men would still be evident when Amundsen remembered Cook’s contribution to the Belgica: ‘He, of all the ship’s company, was the one man of unfaltering courage, unfailing hope, endless cheerfulness, and unwearied kindness. When anyone was sick, he was at his bedside to comfort him; when in any way disheartened, he was there to encourage and inspire. And not only was his faith undaunted, but his ingenuity and enterprise were boundless.’16

These were characteristics the whole Belgica crew came to rely on, as they looked to Cook to help them through an expedition that at times became a living nightmare. Just eight days after leaving Isla de los Estados off the southern tip of South America in January 1898, the Belgica was hit by tragedy when the 20-year-old Norwegian Carl Wiencke fell into the sea. Cook tried to save Wiencke by pulling a line Wiencke had managed to grab hold of, but he slowly felt Wiencke’s grip loosen and then stood horror-stricken with the rest of the crew as they watched him die in the freezing water.

Following Wiencke’s death, the expedition tried to focus on the task ahead of them, spending the next few weeks collecting flora and fauna and geological samples. As they did so, they were frequently left open-mouthed by the vast swathes of new Antarctic land they discovered containing some of the most beautiful scenery on Earth. ‘Everything about us had an other-world appearance,’ Cook wrote about their first landing. ‘The scenery, the life, the clouds, the atmosphere, the water – everything wore an air of mystery.’ But in February, they were forced to become the first people to spend a winter in Antarctica after their ship became stuck in ice (it is now thought de Gerlache did this deliberately, but he kept this from the others).

Living through an Antarctic winter meant enduring two months of continuous darkness, freezing cold temperatures, and the constant fear that their ship would be crushed by the ice. The experience took a great mental and physical toll. The health of most expedition members deteriorated alarmingly – one of them died of heart failure and another was left so mentally disturbed that he spent the rest of his life in an institution. It was largely down to Cook that things were not even worse. He took his physician duties incredibly seriously, diligently interviewing every crew member to understand their mental state and organising skiing trips to encourage them to exercise. And when the crew grew listless and tired and started experiencing headaches and fluctuating heart rates, Cook was perceptive enough to recognise the early signs of scurvy. Remembering that the Inuit he had met in Greenland had not suffered from scurvy, he wondered if there was something in their diet of fresh meat that prevented it, and so he ordered the ship’s crew to eat fresh penguin and seal meat instead of the canned food they had been living on. It was a moment of brilliance that almost certainly saved lives.

And when the long Arctic night finally lifted and the Belgica celebrated the sun’s return, it was Cook who drove the crew on to find a way to escape the ice. The other expedition members had a fatalistic attitude to the ice, believing it to be so strong that they had no choice but to wait until it freed them. But Cook argued that spending another winter stuck in the ice would inevitably mean more deaths, and so it was their moral duty to do everything they could to try to get free. At first, he was derided as an unrealistic dreamer, Amundsen later remembering that it seemed ‘at first like a mad undertaking’.17 But he eventually persuaded the others to try his idea of digging trenches between the ship and an open basin of water not far away. When the ice finally cracked, Cook thought, it would do so along the lines of the trenches and they would be able to reach the basin, from where they might be able to get to the open sea.

This initial plan did not work, so they instead tried cutting out blocks of ice to create a waterway between them and the basin. When friction meant they were unable to move the blocks they had cut, it was Cook who worked out how to cut the blocks in a shape that would make them easy to remove. After a month of back-breaking work, they had removed enough ice for the Belgica to make it to the basin, and in March 1899 they finally reached the open sea after over a year trapped in ice. ‘The miracle happened – exactly what Cook had predicted,’ Amundsen wrote. ‘The ice opened up and the lane to the sea ran directly to our basin!’

The Belgica made its way back to South America, where Cook said goodbye to his friends and travelled up to Uruguay, where he received the awful news that his fiancée Anna had died. Her health had apparently improved after he left, but then declined after newspapers reported that the Belgica was missing and its crew feared dead.

When he got back to New York, Cook returned to his medical practice, but he also gave lectures about his polar travels, had an article about the Belgica published by the New York Herald, and wrote a memoir about his time in Antarctica. Called Through the First Antarctic Night, it was the first English-language account of the expedition and it received good reviews, helping build Cook’s reputation as the only living American who had explored both the Arctic and Antarctic. In 1901, he visited Europe to take part in the Commission de la Belgica that was to prepare the Belgica’s data for publication, and while in Europe he visited London and met both Ernest Shackleton and Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

On Cook’s return to the United States, he gave the impression that he had finally got exploration out of his system, telling a journalist that ‘I have been exploring for many years now, and I think I’ll give someone else a chance’.18 His medical practice was doing better than ever, and he met and married a wealthy 24-year-old widow called Marie Hunt, writing to Amundsen that their marriage would mean ‘my polar adventures will be at an end’. When he married Marie, he also adopted her young daughter, Ruth, and shortly after the wedding Marie gave birth to a baby girl they named Helen.

Now 37, Cook was earning good money and finally had the family life that had been cruelly taken from him with the deaths of his first wife and baby daughter over a decade earlier. But when he was asked to join a relief expedition for Robert Peary, who was in the Arctic and had not been heard from for some time, Cook left his family and boarded a boat for the Arctic. They found Peary in north-western Greenland, where he had spent the last two years on two failed attempts to reach the North Pole. Cook examined him and was alarmed to find that his skin had turned a grey-green colour, his eyes were dull and most of his toes had been lost to frostbite. Worried about Peary’s health, Cook urged him to come back to the United States for medical treatment, but Peary insisted on staying for one more try for the Pole, and Cook returned without him.

Cook’s life was then changed once again by an article he read, this time about Mount McKinley (now called Denali) in Alaska. It had been confirmed as North America’s highest peak five years earlier and no one was known to have reached the top. Because doing so would mean crossing the world’s largest glaciers outside of Greenland and Antarctica, Cook thought his experience of this kind of terrain meant it was a challenge he would be ideally suited to.

He first tried to climb McKinley in 1903, but the expedition ended in failure when his party had to turn back after coming to an impassable ridge. By the time they returned to civilisation they were almost starving and their clothes were in rags, but they had at least made history by becoming the first known people to circumnavigate the mountain. Three years later, in 1906, he tried again. One of his group, the 39-year-old Columbia University physicist Professor Herschel Parker, turned back when they were still miles from the top, and others in the party then went off on their own to hunt big game. But Cook and Ed Barrill, a Montanan who was helping with the horses, pressed on, apparently without any hope of reaching the top but wanting to get as far as possible to identify the best route for another attempt the following year. But when they returned, it was with the news that they had made quicker-than-expected progress and had carried on through howling winds and freezing temperatures until, on 16 September 1906, they became the first ever people known to have reached McKinley’s summit.

Their conquest of McKinley was front-page news, The New York Times reporting that ‘Cook’s feat is particularly notable, as his is the first ascent of the mountain on record and followed repeated failures’.19 It was an achievement that confirmed him as one of America’s leading explorers. He was elected president of the Explorers Club, asked to lecture at the Association of American Geographers, honoured at the American Alpine Club annual dinner, and was guest of honour at a National Geographic Society banquet. At the Geographic Society event, the inventor Alexander Graham Bell introduced him as ‘one of the few Americans, if not the only American, who had explored both extremes of the world’, and said his ascent of McKinley meant he had now also ‘been to the top of the American continent, and therefore to the top of the world’.20

His new-found prestige also led to an approach from the millionaire John R. Bradley, who offered to finance an Arctic expedition where Cook would study the Inuit while Bradley hunted big game. Cook agreed, and they began making preparations. Then in June 1907, just weeks before they were due to leave, they were dining together when Cook asked Bradley if he would be interested in trying for the North Pole.

‘Not I,’ said Bradley. ‘Would you like to try for it?’

‘There is nothing I would rather do,’ Cook said. ‘It is the ambition of my life.’

3

DR COOK, I BELIEVE

It was the evening of Friday, 3 September, by the time Philip Gibbs arrived in Copenhagen, and he was tired and had a headache after travelling all day.

He asked a taxi driver to take him somewhere he could get a strong coffee and write an article for the next day’s Daily Chronicle and, as the taxi drove him through streets adorned with bunting and countless Danish and American flags that had been put up for Cook’s arrival, he thought about the task ahead of him.

Covering a story of this magnitude was a chance to make a name for himself, but the odds seemed stacked against him. He did not speak any Danish, had no contacts in Copenhagen, and did not even know if Cook had arrived in the city yet. He was also arriving a day later than other journalists, and even before he left London another newspaper had published Cook’s own account of reaching the North Pole.

It was the New York Herald that had secured what was one of the biggest exclusives in newspaper history, and it had come to them through pure luck. Because the Herald had published Cook’s account of the Belgica expedition in 1899, Cook thought it was the obvious newspaper to offer his story of reaching the Pole. So at Lerwick in the Shetland Islands, he had sent the Herald a message telling them he was leaving a 2,000-word article at the telegraph office that they could print if they agreed to pay him $3,000. This was a sum the average American would take years to earn, but it represented a bargain for an exclusive account of an era-defining story. The Herald quickly agreed, and the next day published his article about how he had reached the Pole under the proud, if overlong, headline, ‘The North Pole is discovered by Dr Frederick Cook, who cables to the Herald an exclusive account of how he set the American flag on the world’s top’.1