8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

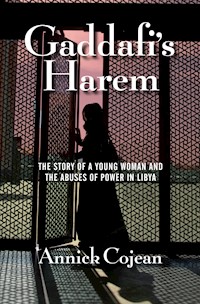

Soraya was a schoolgirl in the coastal town of Sirte, when she was given the honour of presenting a bouquet of flowers to Colonel Gaddafi, "the Guide," on a visit he was making the following week. This one meeting - a presentation of flowers, a pat on the head from Gaddafi - changed Soraya's life forever. Soon afterwards, she was summoned to Bab al-Azizia, Gaddafi's palatial compound near Tripoli, where she joined a number of young women who were violently abused, raped and degraded by Gaddafi. Heartwrenchingly tragic but ultimately redemptive, Soraya's story is the first of many that are just now beginning to be heard. In Gaddafi's Harem, Le Monde special correspondent Annick Cojean gives a voice to Soraya's story, and supplements her investigation into Gaddafi's abuses of power through interviews with other women who were abused by Gaddafi, and those who were involved with his regime, including a driver who ferried women to the compound, and Gaddafi's former Chief of Security. Gaddafi's Harem is an astonishing portrait of the essence of dictatorship: how power gone unchecked can wreak havoc on the most intensely personal level, as well as a document of great significance to the new Libya.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Gaddafi’s Harem

Gaddafi’s Harem

ANNICK COJEAN

Translated from the French by

Marjolijn de Jager

Grove Press UK

First published in the United States of America in 2013 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in French in 2013 by Editions Grasset & Fasquelle

Copyright ©Annick Cojean, 2013

Translation copyright © Marjolijn de Jager, 2013

The moral right of Annick Cojean to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Marjolijn de Jager to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

HB ISBN 978 1 61185 610 1

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 981 2

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

To my mother, always.

To Marie-Gabrielle, Anne, Pipole:

the crucial ones.

“We in the Jamahiriya and the great revolution affirm

our respect for women and raise their flag. We have decided to

wholly liberate the women of Libya in order to rescue them from

a world of oppression and subjugation in such a way that they will become

masters of their own destiny in a democratic setting where they will have the same

opportunities as the other members of society […]

We call for a revolution to liberate the women of the Arab nation,

which will be a bomb to shake up the entire Arab region, inciting

female prisoners, whether in palaces or marketplaces, to rebel against their

jailers, their exploiters, and their oppressors. This call is certain to

cause profound echoes and repercussions in the entire

Arab nation and in the world at large. Today is not just any day,

it is the beginning of the end of the era of harems and slaves […]”

Muammar Gaddafi, September 1, 1981:

the anniversary of the revolution, introducing

the first women to receive diplomas from the

Military Academy for Women

Contents

Prologue

PART ONE: SORAYA’S STORY

1. Childhood

2. Prisoner

3. Bab al-Azizia

4. Ramadan

5. Harem

6. Africa

7. Hicham

8. Escape

9. Paris

10. Cogwheels

11. Liberation

PART TWO: THE INVESTIGATION

1. In Soraya’s Footsteps

2. “Libya,” Khadija, Leila . . . and So Many More

3. The Amazons

4. The Predator

5. Master of the Universe

6. Mansour Daw

7. Accomplices and Providers

8. Mabrouka

9. A Military Weapon

Epilogue

Chronology

Author’s Acknowledgments

About the Translator

Prologue

First, there is Soraya.

Soraya and her dark eyes, her sullen mouth, and her big resounding laugh. Soraya, who moves quick as lightning from laughter to tears, from exuberance to despondency, from cuddly affection to the hostility of the wounded. Soraya and her secret, her sorrow, her rebellion. Soraya and her astonishing story of a joyful little girl thrown into the claws of an ogre.

She is the reason for this book.

I met her in October 2011, on one of those jubilant and chaotic days following the capture and death of the dictator Muammar Gaddafi. I was in Tripoli for the newspaper Le Monde investigating the role of women in the revolution. It was a frenzied period and the subject fascinated me.

I was no expert on Libya. In fact, it was my first time visiting the country. I was enthralled by the incredible courage of those fighting to overthrow the tyrant who had ruled for forty-two years, but also genuinely intrigued by the complete absence of women in the films, photographs, and reports that had recently appeared. The other insurrections of the Arab Spring and the wind of hope that had blown across this region of the world had shown the strength of the Tunisian women, present everywhere in public debates, and the confidence and spirit of Egyptian women, whose courage was clear as they demonstrated on Tahrir Square in Cairo. But where were the Libyan women? What had they been doing during the revolution? Was it a revolution they had wanted, initiated, supported? Why were they hiding? Or, more likely, why were they kept from view in this country that was so little known, whose image was monopolized by their buffoon of a leader, who had made the guards of his female corps—the famous Amazons—into the standard-bearers of his own revolution?

Male colleagues who had followed the rebellion from Benghazi to Sirte had told me they’d never come across any women other than a few shadows draped in black veils, since the Libyan fighters had systematically refused them any access to their mothers, wives, or sisters. “Perhaps you’ll have better luck!” they said to me with a touch of irony, convinced that in this country history is never written by women, no matter what.

On the first point they were not incorrect. Being a female journalist in the most impenetrable of countries offers the wonderful advantage of having access to the entire society and not just to its men. Consequently, it took me just a few days and many encounters to understand that the role of women in the Libyan revolution had been not only important but, in fact, vital to its success. A man who was one of the rebel leaders told me that women had formed “the secret weapon of the rebellion.” They had encouraged, fed, hidden, transported, looked after, and equipped the fighters, as well as providing them with information. They had moved money to purchase arms, spied on Gaddafi’s troops on behalf of NATO, redirected tons of medications, including from the hospital run by the adopted daughter of Muammar Gaddafi (the same one he—untruthfully—said had died after the Americans bombed his residence in 1986). These women had risked unbelievable things: arrest, torture, and rape. Rape—considered to be the worst of all crimes in Libya—was common practice and an authorized weapon of war. They had committed themselves body and soul to this revolution. They were fanatic, spectacular, heroic. “Women had a personal account to settle with the Colonel,” one of them told me.

A “personal account” . . . I didn’t immediately understand the significance of this remark. Having just endured four decades of dictatorship, didn’t every Libyan have a communal account to settle with the despot? The confiscation of individual rights and liberties, the bloody repression of opponents, the deterioration of the health and education systems, the disastrous state of the country’s infrastructure, the impoverishment of the population, the collapse of culture, the misappropriation of oil profits, and the isolation on the international stage . . . why then this “personal account” of women? Had the author of the Green Book not endlessly proclaimed that men and women were equal? Had he not systematically presented himself as their fierce defender, raising the legal age for marriage to twenty, condemning polygamy and the abuses of the patriarchal society, granting more rights to divorced women than existed in most other Muslim countries, and founding a Military Academy for Women open to candidates from all over the world? “Nonsense, hypocrisy, travesty!” a famous woman judge would later tell me. “We were all his potential prey.”

It was at that same time that I first met Soraya. Our paths crossed the morning of October 29. I was completing my investigation and was ready to leave Tripoli the next day to go back to Paris, via Tunisia. I was sorry to be going home. Although, admittedly, I had obtained an answer to my first question, concerning women’s participation in the revolution, and was returning with a whole supply of stories and detailed accounts that illustrated their struggle, so many questions remained unanswered. The rapes perpetrated en masse by Gaddafi’s mercenaries and troops were an insurmountable taboo, locking authorities, families, and women’s organizations inside a hostile silence. The International Criminal Court, which had launched an investigation into these rapes, was itself confronted with terrible difficulties when its lawyers tried to meet with the victims. As for the sufferings that women endured before the revolution, these were brought up only as rumors, accompanied by many deep sighs and furtive glances. “What’s the use of bringing up such vile and unforgivable practices and crimes?” I’d often hear. Never a first-person testimony. Not even the slightest story from a victim that might implicate the so-called Guide.

But then Soraya arrived. She was wearing a black shawl covering a mass of thick hair pulled into a bun, large sunglasses, and loosely flowing pants. Full lips gave her the appearance of an Angelina Jolie look-alike, and when she smiled a childlike spark lit up her face, which was beautiful even though already etched by life. “How old do you think I am?” she asked as she took off her glasses. She waited, anxiously, and then spoke before I could answer: “I feel like I’m forty-two!” To her that was old—she was just twenty-two.

It was a brilliant day in Tripoli, a city on edge. Muammar Gaddafi had been dead for more than a week; the National Transitional Council had officially declared the country’s liberation; and Green Square, rebaptized to its former name, the Square of the Martyrs, had seen another crowd of euphoric Tripoli inhabitants come together the previous night, chanting the names of Allah and Libya in a performance of revolutionary songs and bursts of Kalashnikov fire. Each city district had bought a camel and slaughtered it in front of a mosque, sharing it with refugees from towns that had been devastated in the war. They said they were “united” and “in solidarity,” “happier than they could ever remember being.” They were also worn out, completely spent. Incapable of going back to work and picking up the normal routine. Libya without Gaddafi . . . it was unimaginable.

Gaudy vehicles kept on crossing the city, discharging rebels from hoods, roofs, and car doors, flags blowing in the wind. The drivers were honking, each brandishing a weapon like a treasured girlfriend you might take to a party. They were shouting “Allahu Akbar,” embracing, making the V for Victory sign, a red-black-and-green scarf tied around his head pirate style or worn as an armband, and never mind the fact that not every last one of them had fought from the first moment on or with the same courage. Since the fall of Sirte, the Guide’s last bastion, and his immediate execution, everyone was declaring himself a rebel.

Soraya was looking at them from a distance and feeling depressed.

Was it the atmosphere of rowdy joy that made the malaise she’d felt since the Guide’s death more bitter? Was it the glorification of the revolution’s “martyrs” and “heroes” that took her back to her sad status of secret, unwanted, shameful victim? Did the revolution make her appraise the disaster of her life thus far? She had no words for it, was unable to explain it. All she felt was the burning sense of utter injustice. The anguish of being unable to express her grief and howl her rebellion. The terror of having her wretchedness, unheard of in Libya and much too difficult to explain, summarily dismissed. It wasn’t possible. It wasn’t right.

She was nibbling at her shawl, nervously covering the lower half of her face. Tears appeared on her cheeks, but she quickly wiped them away. “Muammar Gaddafi ruined my life,” she said. She had to talk—the memories were too much to bear silently. “I have scars,” she said, scars that were causing her nightmares. “No matter what I say, no one will ever know where I come from or what I’ve been through. No one could ever imagine. No one.” She shook her head in despair. “When I saw Gaddafi’s body displayed to the crowd I felt a brief moment of pleasure. Then I had a terrible taste in my mouth. I had wanted him to live. To be captured and put on trial, to be judged by an international court. I wanted him to account for his actions.”

For Soraya was a victim. One of those victims that Libyan society doesn’t want to hear about. One of those victims whose dishonor and humiliation reflect on the whole family and the entire nation. One of those victims who are so disturbing and unsettling that it’s easier to make them the culprits. Guilty of having been victimized . . . With all of the strength a twenty-two-year-old girl could muster, Soraya energetically refused this. She dreamed of justice. She wanted to testify. What had been done to her and to so many others seemed to her neither innocuous nor forgivable. What was her story? She was about to tell it: the story of a barely fifteen-year-old girl whom Muammar Gaddafi noticed during a visit to her school and abducted the following day to become his sexual slave, together with other young girls. Imprisoned for several years inside the fortified residence of Bab al-Azizia, she was beaten, raped, and exposed to every perversion of a sex-obsessed tyrant. He had robbed her of her virginity and her youth, thereby preventing her from having any kind of respectable future in Libya’s society. She was bitterly aware of it. After weeping and lamenting over her situation, her family ultimately decided that she was no more than a slut. Beyond redemption. She smoked, never went out anymore, didn’t know where to go. I was speechless.

I returned to France shattered by Soraya’s story and reported it in an article in Le Monde, without revealing either her face or her identity. That would be too dangerous; they had already made her suffer enough. But then the story was picked up and translated all over the world. It was the first time that an account from one of the young women of that mysterious place of Bab al-Azizia had been circulated. Pro-Gaddafi websites denied it vehemently, indignant that the image of their alleged hero, who had done so much for the “liberation” of women, should be thus vilified. Although they had no illusions about the mores of the Guide, others considered it so horrifying that they had trouble believing it. The international media tried to find Soraya, but in vain.

I didn’t doubt her story for a second, as very similar tales that proved the existence of many other Sorayas were reaching me. I learned that hundreds of young women had been abducted for an hour, a night, a week, or years, and been forced to submit to Gaddafi’s sexual fantasies and violence by force or through blackmail; that he had networks available to him involving diplomats, military men, bodyguards, employees of the administration and the so-called Department of Protocol whose central mission it was to provide their master with young women—or young men—for his daily consumption. I learned that fathers and husbands would keep their daughters and wives confined in order to keep them away from the eyes and lust of the Guide. I found out that, born into a family of extremely poor Bedouins, Gaddafi was a tyrant who ruled through sex, obsessed with the idea of one day possessing the wives or daughters of the rich and powerful, of his ministers and generals, of chiefs of state and monarchs. He was prepared to pay the price. Any price. For him there were no limits whatsoever.

But the new Libya isn’t ready to talk of this. Taboo! However, no one hesitates to pour scorn on Gaddafi and to demand that light be shed on his forty-two years of depravity and absolute power. They list the physical abuse of political prisoners, the atrocities committed against opponents, the tortures and murders of rebels. They tirelessly condemn his tyranny andcorruption, his deception and madness, his manipulations andperversions. And they insist on reparation for victims. But no one wants to hear about the hundreds of young girls whom he enslaved and raped. Those girls should just disappear or emigrate, wrapped in a veil, their grief bundled up inside a bag. The simplest thing yet would be for them to die. And some of the men in their families are prepared to take care of that.

I returned to Libya to see Soraya again. I collected other stories and tried to probe the networks of those under the tyrant’s heel. It would prove to be a high-pressure investigation. Victims and witnesses are still living in terror of tackling the subject. Some are the target of threats and intimidation. “For the sake of Libya, and for your own sake, drop this investigation!” some people advised me before abruptly hanging up the phone. And from his prison in Misrata, where he now spends his days reading the Koran, a bearded young man—who participated in trafficking young girls—told me in exasperation: “Gaddafi is dead! Dead! Why do you want to dig up his shameful secrets?” The minister of defense, Oussama Jouili, had a very similar position: “It’s a matter of national shame and humiliation. When I think of the affronts perpetrated on so many young people, soldiers included, I feel nothing but disgust! I assure you, the best thing to do is to keep quiet. The Libyans feel collectively tainted and want to turn the page.”

So there are crimes to be condemned and others to be camouflaged like dirty little secrets? Some victims are good and noble and others are ignominious? There are those who must be honored, favored, recompensed, and those on whom it is critical to “turn the page”? No. That is unacceptable. Soraya’s story is not an anecdote. Crimes against women—treated so casually, not to say complacently, throughout the world—are not a trivial matter.

Soraya’s story is courageous and should be read as a testimony, a historical document. I wrote it as she dictated it to me. She is eloquent, has an excellent memory, and cannot bear the thought of a conspiracy of silence. There is undoubtedly no criminal court that will one day bring her justice. Perhaps Libya will never even recognize the suffering of Muammar Gaddafi’s “prey” under a system that was created in his image. But, at least, while he was strutting about at the UN as if he were the master of the universe, while other nations rolled out the red carpet for him and welcomed him with great fanfare, while his Amazons were a subject of curiosity, fascination, or amusement, her testimony will be there to prove that at home, in his vast residence of Bab al-Azizia—or rather in its humid basements—Muammar Gaddafi was holding captive young girls who were still only children when they arrived.

PART ONE

SORAYA’S STORY

1

CHILDHOOD

I was born in Marag, a small town in the region of Djebel Akhdar—the Green Mountain—not far from the Egyptian border, on February 17, 1989. Yes, February 17! It’s impossible for Libyans not to understand the significance of that date: it’s the day the revolution that ousted Gaddafi from power began in 2011. In other words, it’s a day that’s destined to become a national holiday, and that pleases me.

Three brothers came before me, and two more were born after me, as well as my little sister. But I was the first girl, which made my father wild with joy. He so wanted a girl. He wanted a Soraya. He’d thought of that name well before he was married. And he often told me how he felt when he saw me for the first time: “You were so pretty! So very pretty!” He was so elated that on the seventh day after my birth the customary celebration was as grand as a wedding party. The house was full of guests, music, a large buffet. He wanted everything for his daughter—the same opportunities, the same chances in life, the same rights as my brothers had. Even today he says that he had dreamed I would become a doctor. And it’s true that he made me register for natural science courses in secondary school. Had my life followed a normal course maybe I really would have studied medicine. Who knows? But don’t talk to me about having the same chances in life as my brothers. You can forget that! There’s not a Libyan woman alive who would believe that. All you need to do is see how my mother, despite her being so modern, ended up having to abandon most of her dreams.

Her dreams were boundless, and now all of them are broken. She was born in Morocco at the home of her grandmother, whom she adored. But her parents were Tunisian. She had a great deal of freedom because as a young girl she went to Paris to be trained as a hairdresser. A real dream, right? That’s where she met Papa, at a big dinner one night during Ramadan. He was working for the country’s foreign information service and spending long periods of time at the Libyan Embassy. He, too, loved Paris. The atmosphere was so lighthearted, so joyful, compared to the oppressive Libyan climate. He could have taken courses at the Alliance Française, as acquaintances had suggested, but he was too carefree and preferred going out, wandering around, grabbing every minute of freedom he could manage. Today he regrets not being able to speak French. It would certainly have changed our life. In any event, as soon as he met Mama he quickly made up his mind. He asked for her hand, and the wedding took place in Fez, where her grandmother still lived, and then presto, all smug, he took her back with him to Libya.

What a shock for my mother! She never imagined she’d be living in the Middle Ages. She who was so chic, so careful to be stylish, well coiffed, well made-up, she now had to drape herself in the traditional white veil and keep her outings to a minimum. She was like a caged tiger. She felt cheated and trapped. It was nothing like the life that Papa had made her believe she’d have. He’d talked about traveling between France and Libya, about her work, which she could develop while going from one country to the other. Within days of getting married, she found herself in the land of the Bedouins. She became depressed. So Papa moved the family to Benghazi, the second largest city in Libya, in the eastern part of the country. A provincial town, but still considered to be a little antiauthoritarian compared to the power in Tripoli. He couldn’t take her to Paris, a city he himself still continued to visit, but at least she’d be living in a large city and could develop her family business. As if the hair salon could console her!

Mama kept on brooding and dreaming of Paris. To us little ones she spoke of her walks on the Champs-Elysées, having tea with her women friends on café terraces. She would talk about the freedom that French women had, and also of the social welfare system, labor union rights, the boldness of the press. Paris, Paris, Paris. In the end this kind of talk bored us kids. But it made my father feel guilty. He had envisioned starting a small business in Paris, a restaurant in the fifteenth arrondissement, which Mama could have run. Sadly, he soon had a fight with his business partner and the project fell apart. At the time, he almost bought an apartment in the Défense area for twenty-five thousand dollars, but he didn’t want to take the risk and still regrets that, now that it has become one of the city’s most exclusive neighborhoods.

So my earliest school memories are from Benghazi. They are already a bit blurry but I do recall that it was a happy time. The school’s name was the Lion Cubs of the Revolution and I had four girlfriends there; we were inseparable. I was the comedian of the group—my specialty was imitating the teachers as soon as they left the classroom, or mimicking the principal. It seems I have a gift for capturing people’s looks and expressions. We five would cry with laughter together. I had an F in math but was the best of my class in Arabic.

Papa wasn’t earning much and Mama’s work became indispensable. In fact, the family’s finances soon depended on her. She was working day and night, living in the hope that something would happen to take us far away from Libya. I knew she was different from other mothers and at school they’d sometimes treat me disdainfully as “the daughter of that Tunisian woman.” That hurt. Tunisian women had the reputation of being modern, emancipated, and in Benghazi those were not considered to be fine qualities. Foolishly, the fact that my mother was Tunisian upset me. I almost held it against my father that he hadn’t chosen a wife from his own country. Why did he need to marry a foreigner? Had he given any thought to his children? My God, how stupid I was!

The year I turned eleven, Papa announced that we were moving to Sirte, a city between Benghazi and Tripoli, also on the Mediterranean coast. He wanted to be closer to his birthplace, to his father—a highly traditional man with four wives—as well as to his brothers and cousins. That’s how it is in Libya. Every family member tries to stay close to home—that supposedly gives them strength and unconditional support. In Benghazi, without roots or relations, we were like orphans. Or so, at least, Papa explained it to us. But I myself took this news as a complete catastrophe. Leave my school? My friends? What a disaster! It made me sick. Physically sick. I was in bed for two weeks, incapable of getting up to go to the new school.

But in the end I went. With lead in my shoes and knowing all too soon that I wasn’t going to be happy there. First of all, you need to understand that we were moving to Gaddafi’s birthplace. I haven’t mentioned him yet because at home he was neither a concern nor a frequent topic of conversation. Mama clearly detested him. She’d change channels as soon as he appeared on television. She called him “the unkempt one” and, shaking her head, she’d ask repeatedly: “Honestly now, does that guy really have the face of a president?” I think Papa was afraid of talking this way about Gaddafi, so he’d remain silent. We all sensed intuitively that the less we spoke of him the better it was, since the slightest mention of him outside the family circle might be reported and cause us a great deal of trouble. So we had no photograph of him in our house, and weren’t involved in anything the least bit political. Let’s just say that instinctively we were all very cautious.

At school, on the other hand, it was pure adoration. His image was everywhere; every morning we’d sing the national anthem in front of an immense poster of him, which was attached to the green flag; and we’d cry: “You are our Guide, we walk behind You, blah blah blah”; and in class or during recess, students would talk with pure adulation about the man they referred to as “my cousin Muammar,” “my uncle Muammar,” while the teachers spoke of him as a demigod. No, as a god. He was good; he watched over his children; he was all-powerful. We all had to call him “Papa Muammar.” To us he seemed gigantic.

Although we moved to Sirte to be closer to the family and feel more integrated in a community, things didn’t work out this way. Basking in the glow of their blood relationship or connection to Gaddafi, the people of Sirte felt they were the masters of the world. Let’s just say that, when confronted with the hicks and boors from other towns, they felt like aristocrats, regulars at the court. You’re from Zliten? How gross! From Benghazi? Ridiculous. From Tunisia? Embarrassing!

No matter what she did, Mama was truly a source of disgrace. And when she opened a nice-looking hair salon in the center of town not far from our building in Dubai Street, the contempt for her only increased, though the elegant women of Sirte still came running. My mother was really talented. Everyone recognized her skill in creating the finest hairdos in the city and doing fabulous makeup. I’m quite sure that she was envied. But you have no idea how repressed Sirte is through its traditionalism and prudishness. A woman without a veil can be insulted on the streets. And even with a veil she is suspect. What in the world is she doing outside? She must be looking for an adventure or maybe she’s having an affair. People spy on one another, neighbors watch the comings and goings of the house across from them, families are jealous of each other, protect their daughters, and gossip about everyone else. The tattletales are working around the clock.

So at school it was double trouble. Not only was I the daughter of “that Tunisian woman,” but I was also “the girl from the salon.” They put me at a desk all by myself, apart from the other students. And I never managed to have a Libyan girlfriend. Fortunately, after a while I became friendly with the daughter of a Libyan man and a Palestinian woman. Then with a Moroccan girl and then with the daughter of a Libyan and an Egyptian woman. But never with any of the local girls. Even when I lied one day and said my mother was Moroccan, which seemed less serious to me than being from Tunisia. But, no, it was worse. So basically my life revolved around the hair salon. It became my kingdom.

I’d run over there as soon as classes were over—and it was there that I came back to life after school. It was so wonderful! First of all because I was helping Mama and that was a delightful feeling, but also because I liked the work. My mother never stopped and, although she had four employees, she was constantly running from one customer to the next. They did hair, makeup, and skin treatments. And I can assure you that in Sirte, although the women may well be hiding beneath a veil, they’re still exceedingly demanding and incredibly sophisticated. I specialized in removing hair from the face and eyebrows, using a silk thread that I’d wind between my fingers and manipulate very fast to catch the hair. Much better than tweezers or wax. I’d also prepare women’s faces for the application of makeup, putting on the foundation, after which my mother would take over, working on the eyes before calling for me, saying: “Soraya! The final touch!” And I’d come running to apply lipstick, to check the total result, and to add a dab of perfume.

The salon soon became the meeting place for the city’s elegant women. Meaning the women of the Gaddafi clan, as well. When there were important international summits taking place in Sirte, the women of the different delegations would come to be made beautiful, including the wives of African presidents and of European and American heads of state. It’s strange, but I especially remember the wife of the leader of Nicaragua, who wanted us to draw huge eyes for her below her enormous chignon. One day, one of Gaddafi’s bodyguards, a man called Judia, came to pick up Mama by car to do the hair and makeup of the Guide’s wife. It proved that Mama had acquired quite a reputation! So off she went. She spent several hours taking care of Safia Gaddafi, and was paid a ludicrous sum of money, way below her usual fee. She was furious and felt really humiliated. So when Judia returned later on to take her back there again, she quite simply refused, claiming to have too much work to do. Other times she actually hid, leaving me to explain that she wasn’t there. She really has character, my mother. She never gave an inch.