Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

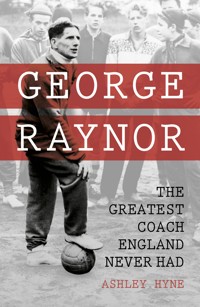

The Guinness Book of Records called him the most successful football coach in history, but English-born George Raynor is the great unknown of British football. His remarkable successes (coaching 'amateur' Sweden to an Olympic Gold medal and a World Cup final) were contrasted bizarrely by how he was and has been treated in England since those heady years. Months after becoming the first Englishman to take a side to the World Cup Final, where he pit his skills against the Brazilians of Pele and Garrincha, Raynor was scratching a living coaching Skegness Town in the Midland League. His death went unrecorded by the local and national press and even today references to him in football books give no insight into this remarkable character: 'a little known clogger' according to one, and in a history of football tactics reference to Raynor is not only fleeting but even his name is misspelt. Yet Raynor unquestionably holds a revered position, internationally, as a leading light of coaching whose impact is still relevant today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 363

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Gordon Pulley

Introduction

1 The Early Years

2 A Playing Career Unfulfilled?

3 The War Years

4 Opportunities in Sweden

5 Olympic Gold

6 Olympic Glory

7 Aftermath

8 A Strange Kind of Triumph

9 The Debacle of 1954

10 Italian Interlude

11 Coventry City

12 The Low Point at Highfield Road

13 Back to Sweden

14 The 1958 World Cup

15 Home at Last

16 The Most Important Book in English Football History

17 Dispute

18 The Descent

Afterword

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ashley Hyne is a barrister and works in the north-west of England. A former football referee, he officiated in over 1,000 matches between 1996 and 2010 in Australia, New Zealand and Indonesia as well as in England. His interest in George Raynor stems from a conversation with Brian Glanville in the early 1980s, when Glanville erroneously informed him that Raynor ‘had been dead for years’. Ashley is currently working on his next book which charts the life of Jesse Carver.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks are due to the following who kindly assisted with information: Sid Raynor; Elsecar Heritage Centre; Paul Taylor and Martin Shaw, historians, Mansfield Town FC; Laura Orridge, Rotherham United FC; Jack Rollin; Royal Army Physical Training Corps museum; Bengt Agren; Sven Axbom; Bengt Berndtsson; Kurt & Marianne Hamrin; Hans Moller; Kalle Palmer; Bengt & Birgit Gustavsson; John Eriksson; Jim Brown; Lol Harvey; Jesper Zenk; Mick French; John Fennell; George Crawford; Lawrie McMenemy; Roy Hodgson; Gordon Pulley; Guy Mowbray; Alan Bates; Vivienne Ashworth; Lina Hedvist; Neil Bonnan; David Magilton; Michael Joyce; Laura Niland; Andrew Kirkham; Denis Clarbrough; Stephen Fay; Dan Fells; Allan Wills; Tommy Wahlsten; Gordon Small; Brian Hyde; Hassanin Mubarak; Anders Johren. Thanks to Karen Bush without whom this book would not have been possible.

FOREWORD BY GORDON PULLEY

Gordon Pulley was a professional footballer who played on the right-wing for Millwall, Gillingham and Peterborough in the Football League after a brief stint with non-league Oswestry Town. His playing career lasted from 1956 to 1966. In total, Gordon played 282 league matches and scored 58 league goals, including a rather controversial goal in a game at Coventry City when George Raynor was seated in the home dugout. Following his playing career, Gordon was a sports teacher at schools and colleges in south London. This foreword will give the reader a taste of what the game was like during the 1950s when Raynor came back to work in England from Sweden.

~

My own introduction to being a professional footballer in the 1950s started when I was doing National Service in the army while I was stationed at Oswestry. After an army game I was asked by Alan Ball Snr (the Oswestry Town FC manager) if I would join his club for £4 per week. After playing only 4 games for the club, I was transferred to Millwall, signing for the club on 17 September 1956 and made my debut at Watford the evening after.

My salary at that time was restricted to £8 per week due to my being on National Service. Having to travel from Oswestry army camp for every game proved to be tiring. Playing in a home game at The Den would see me leave the camp on a Friday evening, stay overnight at my home in the West Midlands and continue to London on the Saturday morning, usually arriving at the ground at approximately 2 p.m. and then returning back home at 10 a.m. A long day for a home game!

The away games were even more difficult. For the away games I had to be in London quite early on the Saturday morning to meet up with the team, which meant staying on Friday night at the Union Jack Club, which was a hostel for the Armed Forces, and I usually arrived back home around midnight and got back to camp on Sunday. On one occasion, due to bad weather, I arrived late at The Den for a home game just as the players were leaving the dressing room, with a player being put in my place, but he was stopped from entering the field, so that I could take my usual place in the team. The game had been going for about 10 minutes before I got on to the field. I still had seven months to go before I left the army, so every weekend followed the same schedule.

There were many professional players stationed at Oswestry at the time, and I imagine that they all had similar travel problems. My first season at Millwall went reasonably well, considering that I was trying to come to terms with my first taste of League football, which I found to be a lot more physical than playing non-league, and also to compete against full-time players whilst still being in the army. I felt that sometimes the management didn’t always appreciate this.

My first season was notable for a good FA Cup run, which saw victories against Brighton, Margate, Crystal Palace and Newcastle United before losing to Birmingham City in the fifth round. Both the Newcastle and Birmingham games attracted gates of 40,000 for both home games at The Den. I well remember defeating Brighton in a replay in an evening game at The Den, because when I reported back to camp the following morning I spent the day locked up in the Guard Room for being absent without leave: the club had forgotten to contact the regiment to arrange for me to have the Monday off.

The Den could be an intimidating ground to play on, and not only for the away side. The home fans would never shy away from letting you know how they felt about your display. It was sometimes very wise to leave the ground long after the fans had gone. Later on, in the early Gillingham days, I would travel by bus to the home games together with quite a few of the fans who lived near to me. The result decided whether we came back on the same bus.

On leaving the army for my first full-time contract with the club, I received a salary of £14 in the first team, plus a win bonus of £4, £11 in the reserves and £8 in the summer. This improved in time to £17, £14 and £11 in the summer. Being a professional footballer in the 1950s was a vastly different proposition to that of today in so many ways. There was no security of long-term contracts. The contracts were for one year only and at the end of each playing season you would receive (by registered mail) the decision of the club. There were three choices open to them: either to retain your services for a further year (usually on the same salary), to give you a free transfer or, the worst of all for a player, to place you on the ‘open to transfer’ list. Being placed on the open to transfer list meant that the club would put a fee on your head, but if no other club had bought you by the time your contract had ended at the end of May (which was only a few short weeks after the season had ended) the club ceased not only to play you, but also retained your resignation, so you were not able to move to another club until someone wanted to pay the fee that they were asking for.

Over a period of time the club could either reduce the fee required, or grant a free transfer to the player in order for him to move on. Either way the player would have been seriously out of pocket, not to mention the stress it would have caused before he finally moved to a club. So in theory you were at that time out of football and at the mercy of the directors. No club, no salary and it was quite legal for football clubs to do this. I was fortunate that my transfer to Gillingham from Millwall went through before my contract had ended. Jimmy Hill was later to call this ‘Soccer Slavery’, which was a good description.

On the playing side, the usual formation of the teams was 3–2–2–3: three defenders, two wing halves, two inside forwards and three front players. The two wing halves would normally support the back three and the two inside forwards would play just behind the front three. With the odd exception, most playing surfaces in those days in the lower divisions were not that good, particularly after Christmas when you were all too often playing on a pitch of sand and mud. Football in the Third Division South and the 4th Divisions tended to be quite physical, but in the 1950s, football was known to be a contact sport, and although most of the defenders were tough and uncompromising in their approach to the game, very few of them found their way in to the referees’ book, no matter how bad the tackles were. I can only remember one opposing player ever being sent off the field in a game that I played in. That was against Bradford Park Avenue, when the then player-manager of Bradford, the legendary tough Ronnie Scoular (formerly of Newcastle United and Scotland fame) grabbed one of the Gillingham players by the throat. It took something extreme to get your marching orders in those days. Certainly a few bad tackles from behind would never get a player in too much trouble: in the 1950s the tackle from behind was quite acceptable to the referees if not to the player on the receiving end.

Although the game was very physical there were very few penalties awarded. I was designated penalty taker for quite a few seasons, but can only remember taking approximately six and they were usually given for hand ball. Although the 3rd and 4th Divisions were well known for their physical approach, there was no real cheating, no shirt pulling, no trying to get an opponent sent off, and for all the tough tackles that were made, it was mainly an honest game. When I was on the receiving end of a strong challenge my first thought was to get to my feet and try to walk away and to show the full-back that he hadn’t hurt me. Not always easy, but most wingers I played with would all do the same. We didn’t want to show the defender that he could kick you out of the game. Our manager would always tell our full-backs that when the winger is trying to take you on, the ball can go past you, the winger can go past you, but not the two together. You have to get one or the other. It appeared to me that nearly all the opposing full-backs in the 1950s used to receive this same advice. When scoring a goal, you might get a pat on the back, a handshake or a well done from a teammate but no more than that.

The goalkeepers were certainly not a protected species in the 1950s. Many a goal was scored with the goalkeeper lying injured on the ground after being challenged by an opponent when attempting to catch a high cross. I well remember one controversial incident when I played in a game for Millwall against Coventry City at Highfield Road in 1956. The Coventry goalkeeper that day was Reg Matthews, who was at that time an England international. He came out to catch a high ball from a right-wing corner and after a strong challenge from a couple of Millwall players he couldn’t hang on to the ball and fell injured to the ground, the ball fell invitingly to my feet which I promptly put into the empty goal. The game was held up for some time, not only to enable Reg to get treatment but due to the Coventry players disputing my goal and also to clear the pitch, after seat pads from the main stand had come raining down over the touchline from irate home fans. My goal was allowed to stand, and we went on to win the game 2–1.

Reg Matthews was later to join Chelsea, and when Chelsea and Millwall played home games on the same Saturdays we would sometimes have a meal together on the train back to the Midlands and to the best of my knowledge the controversial goal was never mentioned.

From my own time of football in the 1950s the two clubs I played for were run by the manager and a trainer who also doubled up as the physio. Most of the training sessions would be lots of running, with laps around the pitch: the main emphasis was on fitness, and very little was seen of the ball. A popular belief in those days from the management was that if you didn’t see much of the ball during the week’s training you would want it more in the games. This was not the view of the players. The only time spent with a ball, apart from the routine Tuesday practice game, was normally to give the goalkeeper some shooting practice and when we organised our own small-sided games on a rough patch of ground behind the terracing. It was only when coaching became more acceptable in time, that the ball skills practices came into their own and the sessions became more enjoyable.

Training was almost always held at the ground, and a lot of it on the pitch, usually in all weathers, which is why the playing surface in the latter part of the season was difficult to play on. It was not unusual to see a very heavy roller used on a Friday to flatten the playing surface.

There weren’t a series of pre-season friendlies in those days: on the Saturday before the season started, there would be a game between the First Team and the Reserves, and that’s all. One season there were only sixteen professionals at the club and five young professionals who were known as ground staff boys, who besides training to be footballers had to do jobs around the ground. When we had a practice match on a Tuesday the manager, Harry Barratt, would often join in to even the teams up. The training kit tended to be several years old and the first arrivals would get the best kit. In many ways Harry could be described as a pre-Brian Clough type of manager, he was a tough competitor during his playing days for Coventry, and he managed in the same way, with a real sense of humour at times. He often used to say to me that he couldn’t understand why I could play so well in one game and so bad the next. He even got his mentor and the former Coventry City manager, Harry Storer, to come and watch our game at Notts Forest, for advice on how to get the best out of me. His favourite comment to me after many a game was ‘You started off bad, and got worse.’

The relationship with a manager tended to depend on whether you were in the first team, playing well, and winning games. When that happened everything was fine but when you were left out of the team, things changed. You were rarely told the bad news by the manager although you would have had a good idea in the week’s training. You only really found out what team you were playing in when the team sheets were pinned on the notice board on a Friday morning and when you were left out of the side – which could be for quite a few weeks – there was usually little contact between the manager and the player, hardly any conversations at all, and you were ignored until you were put back into the side and things improved again.

On one occasion when I was left out of the Gillingham team and not too happy, I followed the advice of several senior professionals. They encouraged me to go and see the manager, Harry Barratt (which I foolishly did), to ask him why I was playing in the second team on the Saturday, to which he replied in a rather loud voice, ‘Because we haven’t got a third team for you to play in,’ and promptly tore me to pieces. I returned to a dressing room full of laughter, as the players had heard every word that was said. What a set up.

But I didn’t fare as badly as one of Gills’ players, Brian Payne, who was involved in a confrontation with Harry Barratt. After an evening reserve game at Crystal Palace, which ended in a heavy defeat, all the team were ordered to report for training next morning. In the team meeting the next morning they were told to expect a hard session of running as punishment for the previous night’s poor display. Barratt said, ‘And if anyone objects and doesn’t want to do the running, then say so now and you can have a week’s wages and leave the club.’ Brian didn’t agree with the manager’s decision, said so and within minutes was out of football and didn’t play league football again. It was quite a usual thing at the time when after a bad defeat, the manager would nearly always vent his anger by ordering the trainer to make the players suffer: the reasons why or how we came to lose a game were never exactly explained – it was always too often that ‘the effort was lacking’ and ‘we hadn’t tried hard enough’ and very little analysis was used to say what we had done wrong, whether individually or as a team. This was also to change when coaches became more involved in the teams.

Life in the Fourth Division could be quite tough travelling-wise, especially for an evening away game when playing against a Northern club. Money was tight and it meant travelling by coach on most occasions, which meant spending all day on a coach and travelling back through the night after the game. At Gillingham we had quite a problem with some of the away fixtures. At an evening game at Barrow in late September or early October, we missed the morning Euston train to the North. It was an early kick-off because they had no floodlights and as there was no other train that would get us there in time for the game, it was decided to go to Heathrow and try to hire a plane. It was a worrying time for the officials, because no club had ever failed to arrive for a Football League fixture. After several hours a plane was hired and we flew to Blackpool which was still quite some distance from Barrow. A fleet of taxis completed the journey. The kick-off was delayed for some time, but after approximately 1 hour’s play and being 6 or 7–0 down it was just too dark to complete the game.

It was the first Football League fixture at that time where the game was abandoned and the result was allowed to stand. And to complete a miserable day, we travelled back overnight on a train. The club received only a nominal fine, because of the high cost of hiring a plane. Further away trips to Walsall, where we arrived with only eight players (the other three had missed the train, although they arrived in time for the game), and to Doncaster and Workington also saw us arrive only just in time to make the kick-off. For the Doncaster game we were travelling by train and were preparing to get off when approaching Doncaster station, only to be told that the train was not scheduled to stop there, and the communication cord had to be pulled by one of our officials. The train came to a halt beyond the station which meant a walk back along the track before taking taxis to the ground.

For the Workington game we had to get changed on the coach and only just made the kick-off once again. Life was never dull on the road with the Gills. Sometimes the coach trips back to Kent from the North could also be difficult after a bad result. Geoff the driver, who also doubled up as the groundsman, was told by the manager that we would be travelling back without any stops unless the manager wanted to stop for the toilet, when the players could do the same: but a good result away from home would see us make several stops at various pubs along the way.

The holiday period was a busy time in the 1950s with games on both Christmas Day and Boxing Day, while over the Easter weekend we would play on Good Friday, Saturday and the Monday. As a footballer in the 1950s we didn’t earn much more than the average worker would have earned and we possibly earned less during the summer: the close season saw most of the players looking for a job to supplement the low summer wage. In the 1950s the summer break was approximately ten weeks long. I did various jobs over quite a few summers, such as working in a timber yard, a labourer and I was once employed by Gillingham with other players to paint the dressing rooms and do odd jobs around the ground. Other times, with my wife and two young girls, we would spend the whole summer back home in the West Midlands, where we both came from, dividing our time between our parent’s homes.

I married my wife Pat during my early days at Millwall, but the only way I could get manager Ron Gray’s permission to get married during the season was to marry in the morning in the Midlands, and play at Coventry in the afternoon, which we did. All the married players at that time would rent houses owned by the club, with the single players living in digs. One football kit would have to last the whole season, and on one occasion when the club played in the FA Cup away at Ashford Town (Kent) and the strips clashed we had to borrow a kit from Margate FC for the game.

We even had to buy our own boots. A pair of new football boots in the 1950s usually had to be broken in before you would want to play a game in them. I would remove the studs, soak the boots in warm water for some time, and after drying them off, would wear them around the house for days until they felt comfortable enough to use for the first time. Two pairs of boots would last me a whole season, one with studs for the soft pitches, and one with moulded rubber studs for when they were firm. When they did wear out, I had to get them repaired myself.

An injury could also cause you real financial problems, because if you got injured playing for the first team and were out of action for quite some time, you would only receive first-team wages for the next four weeks. You would then receive reserve-team money until you were fit and back in the side. This never seemed fair to me, almost like adding insult to injury.

But to be a footballer in the 1950s and 1960s was all that I wanted to be. As players we never thought we were anything special just because we played football, particularly playing in the lower divisions. I always considered myself very much a working-class person who was grateful to be earning a salary doing something that I really enjoyed and of the opinion that it was better than having to work for a living. I had no other plans and looking back it would have been nice to have had the security of a longer contract, better pitches to play on, also a little more protection from the officials, but nevertheless, to be able to earn your living from kicking a ball around took some beating.

Gordon Pulley, 2013

INTRODUCTION

Despite being the most successful national coach in the history of football – an accolade bestowed by the Guinness Book of Records – Raynor is one of the least well known within Great Britain. Rising from humble beginnings as a miner’s son, he became a competent but unexceptional footballer for Second and Third Division clubs before discovering his real forte and beginning a meteoric ascent as a coach.

Dispatched to Sweden after the Second World War, Raynor achieved such success at international level that he clearly came to believe, justifiably, that he would one day be given the responsibility to lead England. His work overseas therefore carries with it the feeling that all was a rehearsal for a triumphant return. However, this was never to come to pass. In this way, Raynor, although an ambassador for English football, became increasingly a reluctant and embittered one.

Against all the odds, he steered Sweden to Olympic Gold and Bronze medals as well as to second and third places in two World Cups, and managed Italian giants Lazio and Juventus. Yet on leaving Sweden in 1958, the man whose services had been recognised with a knighthood from the King of Sweden and a Presidential Medal from the Brazilian Government was inexplicably (or widely presumed to be) shunned by First Division clubs and found himself working at a grammar school in Skegness as a PE teacher.

In his own country George Raynor was, and continues to be, ignored or misunderstood. His successes were received by sceptics and resisted by those who had no genuine interest in seeing England win anything. Even today references to him in football history books are disparaging: ‘A little known clogger,’ according to one, and in another (a history of football tactics no less) reference to Raynor is not only fleeting but his name misspelt. Jonathan Wilson’s binning of Raynor’s impact on the ascendance of Swedish football (and, indeed, European football after the Second World War in general) in his Inverting the Pyramid is astonishing not least in its brevity: ‘Under [Raynor’s] guidance, and advantaged by their wartime neutrality, Sweden won Gold at the 1948 London Olympics, finished third at the 1950 World Cup and then reached the final against [Brazil] in 1958. There, they played a typical WM with man-marking …’ And that’s it!

Did Sweden really play ‘a typical WM’ formation? If they did so play, how could such an antiquated formation produce such success? And, given that it was successful, what influence, if any, did Sweden’s play have on other nations? Moreover, how much a factor was the Swedish neutrality in the war? Particularly in light of the comparative lack of success of Switzerland and Spain who, equally, were neutral in the war.

Is this commonplace ignorance and disdain for Raynor’s achievements an indication that Olympic Gold in 1948 and Bronze in 1952, and a second and third place in the 1958 and 1950 World Cup were commonplace and that his ideas lacked tactical sophistication? Is it evidence that the 7–2 victory over Karl Rappan’s Switzerland in 1946 and a 2–2 draw with Gustav Sebes’ world-beating Hungarians in November 1953 – just days before Hungary beat England 6–3 – were merely the results of luck and chance? Under Raynor’s tutelage, at each and every international competition in which Sweden qualified they ‘medalled’. Yet in England, the nation which yearned so much for a victory their self-belief should have confirmed, there was never a desire to bring Raynor into the fold. He was quite possibly the greatest coach England never had.

George Raynor’s story might ostensibly be regarded as just another straightforward ‘poor boy makes good’ tale, but in fact it is one which, when examined more closely, raises a number of intriguing questions. Apart from the obvious – why his methods were so outstandingly successful – probably the most perplexing and difficult to answer is why his evident talents and experience were never to be called upon by his own country. The purpose of this book is to attempt to answer these questions by examining Raynor’s career in football.

Ashley Hyne, 2014

1

THE EARLY YEARS

Knowing a little about Raynor’s background is instructive, as the part played by the environment and circumstances he grew up in sheds light on the formative influences on his character which would ultimately lead to some of his greatest successes – and later, his bitterest disappointments.

One of four children, George Raynor was born in Elizabeth Street, Hoyland, South Yorkshire, on 13 January 1907. The Raynors lived and grew up in an area dominated by coal mines; George’s father Fred worked as a coal hewer, as did his grandfather, another George. From the age of 16, George’s uncle Wilfred also worked underground, as a coal trammer, a job which involved pulling and pushing the pony-pulled trams to the surface of the pit. George Raynor had no inclination to follow them into the dirt and blackness. He should not be criticised for not wishing to do so. Pit work was frightening, dangerous, and bloody hard work.

Charlie Williams, who would later find fame on TV’s The Comedians, was a miner before becoming a professional footballer and was, himself, coached by Raynor while playing for Skegness Town in the 1960s. Williams wrote briefly about the reality of pit work in his autobiography Ee – I’ve had some laughs:

The first coal face I saw were the Barnsley Seam. It were five, maybe six, feet high. You could stand up in that one. I’ve seen colliers in smaller seams when they’ve had to kneel to get at the coal. And there were sparks flying off them picks. Hand-got coal. No machines then. Hand-got. The colliers picked it down, then they shovelled it. Graft. Them men worked. They deserved every penny they got.

Williams devotes just as much time to discussing the misery experienced by the pit ponies as he does to the miners. This is not accidental, either. The ponies were an integral part of a system that bonded that community, and when Williams writes about the death of ponies – invariably due to the carelessness of some absent-minded trammer leaving a shaft door unlatched – it is not just out of sympathy for the animals but because death was always somewhere close in that darkness.

Nowadays we think of the unity of the mine workers as being implicitly political in nature, but that affiliation arose because of the system the miners worked in. Each miner was dependent on their fellow workers for their survival. This sense of unity would not have been lost on the young George Raynor. He came from a small mining village in South Yorkshire and that same unity bound the community. Power, strength and survival all came from people working together for the common good. Later in life, when he lived and worked in Sweden, Raynor would demonstrate just how creating that same unity of purpose would come as second nature to him and how it would benefit those he worked with.

George excelled academically from an early age. By the end of the First World War the family had moved to No. 6 Hall Street, Hoyland, and at that time Raynor was attending Hoyland Combined School. In his autobiography Football Ambassador at Large, Raynor recounts that he was in Standard 7 at the age of 10 and in August 1919 he was awarded a County Minor scholarship from the West Riding County Council to attend Barnsley and District Holgate Grammar School, which later became Barnsley Grammar School. This would be the school of footballers Brian and Jimmy Greenhoff, and of cricket umpire Dickie Bird.

The scholarship was not, however, the blessing it might have been. Another student of the school, chat show host Michael Parkinson, later bitterly referred to the place in anything but glowing terms: ‘Barnsley Grammar School was to education what myxomatosis was to rabbits.’

Raynor would attend the school as a day boarder from the age of 12 in September 1919 until he was 15 in July 1922. Raynor’s experience of school life was summed up by one incident that he recounted in his autobiography. During a PE class, Captain Henry McNab Bisley, an ex-army school teacher who was taking the lesson, smacked Raynor across the ear for turning up in his vest and underpants – an ‘outfit’ which speaks of the relative deprivation in which Raynor grew up.

Although Raynor was to remark that as a result of that incident he recoiled from physical training, this is not true. George was in fact a self-taught and talented athlete and used his autobiography to explain how he loved sports, and trained himself in athletics.

What Raynor did learn from the incident was that he would never become the same sort of small-minded sadist that Bisley arguably was. He had no time for the type of authoritarians that used sport as an excuse to bully their charges. In his later career, Raynor would assume the role of pastoral carer for his charges, the very antithesis of all that Bisley represented. Raynor’s coaching methods demonstrated conclusively that the reward of proper, supportive tutoring was the flourishing of ability where talent might otherwise have remained inhibited. Over eighty years after Bisley’s life-changing slap, Kurt Hamrin, the wing-star of Sweden in the 1950s, wrote warmly of the type of coach that George Raynor became, saying, ‘He was an incredibly nice man, we lads in the [Swedish national] team referred to him as finagubben’ – which is difficult to translate, but is basically a respectful but familiar nickname equivalent to something like ‘the grand gaffer’.

One cannot know what discussions took place at the Raynor family home before and after George left school about what direction his life should take, but we can be fairly sure that the heartfelt desire of George’s family was not to join the queue into the pit. Forced to leave school at the age of 15 when his father lost his job in 1922, Raynor got an apprenticeship in a local butchery. It was not a sinecure, being often bloody and violent (one of George’s tasks was to kill pigs by hammering a peg between their eyes) but the job, which to modern eyes hardly represents a vindication of a renowned education, would have definitely represented upward social mobility in a mining town.

Hasties, the company George gained the apprenticeship with, were an established local company and one can reasonably believe that the family would have been content with the appointment. However, George’s mind was on participating in sport. He was clearly a talented athlete from an early age, and it was because of his early love of participation and competition that George himself brought the apprenticeship to an end. One of the first indications of his leanings toward sport and away from a normal working life came about one Saturday. George was granted time off to race in the local sprint handicap at Platts Common, just north of Hoyland. He won the race. Then returned, exhilarated, to work and finished his shift.

Irked by the fact that working at Hasties was occupying him on Saturday, ‘the day of sport’, George handed in his notice and went to work as a labourer on a builder’s lorry instead. This was physically demanding and tiring work but there were benefits to be gained from it. He took the job because, in his mind, it would help strengthen him as he matured through his teens – and most importantly of all, it left him free on Saturdays. As Raynor’s cousin Sid, who still lives in Hoyland, wryly comments, ‘He never really did do a proper job, you know.’

Around this time George decided that he wanted to be a professional footballer.

Number 6 Hall Street still exists today, part of the town square of Hoyland; one of a row of terraced houses which face onto a car park. Turning left out of his front door, Raynor would free-wheel his push bike halfway down King Street, and in a side alley next to the tennis and bowling green (where the access road to the Park and Ride is now found) he would devote time to sprint training. It was also there that he would meet his future wife, Phyllis Whitfield.

Phyllis lived at No. 97 Church Street, Elsecar almost next door to the Wesleyan Chapel. She was a member of a Bible Class which was run at the chapel. She knew George liked football and explained to George that the Bible Class had a football team and that if George wanted to play football he could do so on condition that he joined the Bible Class. This George proceeded to do.

The minister running the Bible Class was Thomas Tomlinson. This was the beginning of a life-long friendship between George and Thomas and was George’s introduction into organised football.

The Bible Class played on Furnace Hills in Elsecar. The area still exists, although it’s now beneath 3ft of seeded grass and there are maturing trees dotted around what was the pitch. It can be found on a flat step of ground, on the hill above the Elsecar Heritage Centre; to access it one has to navigate a treacherous course up a muddy path.

It was a popular venue for the local football teams (Elsecar played their home matches there). Alan Crossley (uncle of Welsh international goalkeeper Mark), who I met at Furnace Hills, explained to me that it was used by the local school teams whose pupils would run from King Street School across King Street, along Church Street and all the way up the hill before playing a match and then running back to the school to get changed. But, as Alan said, it was never a grass pitch. Instead Furnace Hills was a dumping ground for the shale that was extracted out of the Elsecar Main Coal Pit, which is likely where George’s father earned his crust.

The shale was dumped on the side of the pitch and this served as impromptu terracing where local spectators would gather to watch the games that were played at the ground.

The bumpy surface made it a difficult pitch to play, and the jagged rocks of shale frequently caused cuts and bruises. Later, in the 1980s, that same shale would be dug out of the soil by some members of the local community, who, impoverished by the extended miner’s strike, were reduced to burning the discarded waste.

George played centre forward for the team in the Sunday School League and helped the club raise money for local charities when playing in the popular Kelley Cup, a local competition. Raynor would look back on those local youth games with great fondness. Half a century later, Raynor could still recall scoring 73 goals for Elsecar Bible Class in one season. Those 73 goals made an impression locally because Mexborough, one of the local Midland League sides, asked George to play in a trial.

The Midland League was a reserve league, featuring both football league reserve sides and some of the best non-league teams in that part of the country and had become a scouting ground for various local football league sides. George jumped at the chance of attending the trial. Only 20 minutes from Elsecar, Mexborough had won the Midland League in the 1925/26 season and during the following season won their way into the first round of the FA Cup, only to lose narrowly to Chesterfield of the Football League.

This contemporary success probably explains why Mexborough did not contact young Raynor following the trial match, despite him scoring twice. It is also a reasonable assumption that Mexborough did not really take to Raynor because he wasn’t the big, bustling centre forward that the Midland League demanded; even when fully grown Raynor was only 5ft 7in in height and 11 stone in weight.

However, it wasn’t long before George had a chance in another trial match; this time for Wombwell, another Midland League side. This time he was more successful and, in July 1929, he signed forms to play for Wombwell for 15s per match. The first decision Wombwell’s management made on signing Raynor was to assess his lack of height, note his speed and place him on the right-wing, a position he would remain in for the rest of his career.

Raynor had a splendid debut for Wombwell, shining in a game against the leaders of the Midland League, Notts County reserves. It was also during that game that an incident occurred which made a deep impression on George, and would later influence the way he coached his players. He describes scoring a goal: ‘I took one pass, raced around two men, took the ball up to the byline and surprised the goalkeeper with a tremendous shot from that almost impossible angle.’ As Raynor gleefully headed back to the halfway line, the side’s resident professional and captain, Denis Jones (formerly with Leicester City), went up to Raynor and instead of offering congratulations, gave him a short, sharp comment to the effect that he should never do that again. The lesson was not lost on George. To succeed in football – particularly in the Midland League between the wars – required self-discipline and subservience to the team. Raynor was happy to defer to the experienced club professional, for his words were those of a person who had already been where Raynor wanted to go, and Jones’ lesson was timeless: unnecessary risk should be avoided at all costs.

It was a lesson he would return to throughout his career, memorably so in one of the first games he saw played in Sweden. In a virtuoso display mirroring that of the young Raynor, a young inside right called Gunnar Gren beat three defenders, rounded the goalkeeper, took the ball back to beat the goalkeeper again and then back-heeled the ball over the line. Raynor brought Gren down to earth with a thud after the game with his imitation of a Denis Jones’ style rocket.

Raynor’s instruction that Gren must pass the ball away as soon as he had beaten his opponent led to a falling out between the two. Gren’s battered pride would subside, a natural instinct to win for the team soon undermining his initial response that he would rather kick the ball into touch than pass, and in Raynor’s words he became one of the finest team-men you could wish to find. Raynor was never unnecessarily harsh on his players, who responded accordingly. He had never forgotten Jones’ lesson that ‘For any player to shoot from the by-line is the height of selfishness, and although he might score once in a hundred times, his selfishness costs his team a goal on most of the other occasions. There is no room in football for the selfish player, the player who puts the glory of scoring a goal above the good of the team.’

Raynor’s performances on the right-wing for Wombwell soon put him in the shop window for some of the local Football League sides. In one of his games, knowing that United’s scout was watching, Raynor played despite having torn a calf muscle shortly before the game; typically undeterred, he played through the game with a heavily strapped leg. The future looked bright when, on 18 May 1930, he signed professional forms for First Division Sheffield United. Just a few weeks earlier George Raynor’s life had changed in a completely different way and, on 3 May, he had married Phyllis Whitfield at the Wesleyan Chapel where they both attended the Bible Class as children; the lay preacher who married them was Tommy Tomlinson.