9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

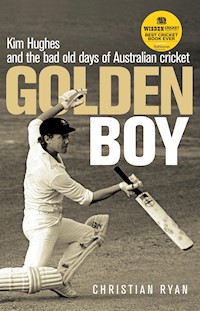

**Voted Wisden Cricket Monthly's best cricket book ever in 2019** WINNER, BEST CRICKET BOOK, BRITISH SPORTS BOOK AWARDS 2010 _________________ Golden Boy is a blistering exposé of the tumultuous Lillee/Marsh/Chappells era of Australian cricket, as viewed through the lens of flawed genius Kim Hughes. _________________ Kim Hughes was one of the most majestic and daring batsmen to play for Australia in the last 40 years. Golden curled and boyishly handsome, his rise and fall as captain and player is unparalleled in cricketing history. He played several innings that count as all-time classics, but it's his tearful resignation from the captaincy that is remembered. Insecure but arrogant, abrasive but charming; in Hughes' character were the seeds of his own destruction. Yet was Hughes' fall partly due to those around him, men who are themselves legends in Australia's cricketing history? Lillee, Marsh, the Chappells, all had their agendas, all were unhappy with his selection and performance as captain - evidenced by Dennis Lillee's tendency to aim bouncers relentlessly at Hughes' head during net practice. Hughes' arrival on the Test scene coincided with the most turbulent time Australian cricket has ever seen - first Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket, then the rebel tours to South Africa. Both had dramatic effects on Hughes' career. As he traces the high points and the low, Christian Ryan sheds new and fascinating light on the cricket - and the cricketers - of the times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR GOLDEN BOY

‘A cracking read . . . An almost tragic but compelling tale of how Hughes tried hard —and failed—to fit his smiling personality into the hard-faced world of his country’s uniquely macho and badly moustached team.’

Giles Richards, The Observer

‘Excellent . . . Graphic . . . Shocking . . . Ryan has extracted some devastating testimony . . . If half of what we read here is true, two Australian legends should hang their heads in shame.’

Simon Wilde, The Times

‘The best cricket read of the year.’

Kevin Mitchell, The Observer

‘A valuable archive of the professional cricketer’s lot during the 1980s—paltry wages, petty officials, vermin-infested hotels and astonishing levels of alcohol consumption . . . Golden Boy provides a fascinating account of Australian cricket’s leanest years.’

Jeffrey Poacher, The Times Literary Supplement

‘Extraordinary . . . A sad tale, told splendidly.’

Alex Massie, The Spectator

‘Absolutely superb, one of the best cricket books I’ve read.’

John Stern, The Wisden Cricketer

‘The wall of silence forced Ryan, a stubborn man, to look elsewhere . . . He has written an entirely credible and deeply absorbing account of Test cricket as it really is lived. It is a grim tale.’

Stephen Fay, The Wisden Cricketer

‘An eye-opening account of an era in Australian cricket which, even 25 years after the bitter denouement, still warrants contemplation.’

The Age

‘The best cricket book in years not written by someone called Gideon Haigh.’

The Sun-Herald

‘An epic piece, shot through with pain . . . It’s heartbreaking to read but such is the quality of Ryan’s work, you can’t stop.’

Tim Blair, The Daily Telegraph

‘Brilliant book . . . A masterpiece . . . One of the best ever written about Australian cricket.’

Ron Reed, Herald Sun

‘Compelling and, at times, sickening reading.’

The Courier-Mail

‘A masterpiece . . . Wonderfully entertaining.’

Cricinfo

‘Wonderful.’

First published in 2009 by Allen & Unwin

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Christian Ryan 2009

The moral right of Christian Ryan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 74237 463 5

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 545 3

Printed in Great Britain

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Mary

Contents

PROLOGUE:In the Nets

1 ‘Let Him Stew’

2 Rare Thing

3 ‘Dead Animals, Bloody Turds, Old Apples, Sponge Cakes . . .’

4 The Crumb-Eaters

5 ‘You’re the Fred Astaire of Cricket’

6 Hungry? ‘I’ve Had Twenty Malt Sandwiches’

7 The View From the Scrapheap

8 ‘Like the Biggest Neon Sign Up at Kings Cross’

9 His Right Knee

10 ‘Bacchus Is Being Absolutely Obnoxious’

11 God Was His Nickname

12 ‘Guys, I’m Going Into the Trenches for You’

13 ‘Gentlemen, Before You Go . . .’

14 The Bulldozer Theory

15 Cape Crusader

16 ‘I Just Remember the Shenanigans Up on the Tenth Floor’

EPILOGUE:Old Men in a Bar

Acknowledgements

Statistics

Interviews

Bibliography

PROLOGUE

In the Nets

The man who was captain looked more like a boy. He stood at the far end of the Sydney Cricket Ground practice nets, and as he waited for the bowler his bat banged the ground, impatiently, not nervously. His smile as he leaned forward revealed two rows of gappy, crooked teeth. Not a wrinkle lined his face. His cheeks and elbows had a pinkish glow, the price of playing cricket nearly every summer day for nineteen consecutive summers. He wore his collar upturned and his shirt unbuttoned to the breastbone, and here, in a triangle down his neck and hairless chest, the skin was crimson. His head was a bottlebrush of curls shooting out in so many directions that his green cap could not contain them. The curls were too dark to be blond yet the sun rebounded off them in a way that told you they weren’t brown. They were golden.

The bowler the captain was waiting for had seldom if ever been called boyish. His chest hair was ropy and black. His bald spot was round as a beer coaster. Captain and bowler knew each other well.

They first played together nine years earlier, November 1974, Western Australia versus South Australia at the WACA Ground. Back then, Kim Hughes was feeling giddy about his big-time debut and Dennis Lillee was on a private crusade. Doctors had diagnosed three stress fractures to his back. Critics—‘poison typewriters’, Lillee called them—had pronounced his career comatose. He had about him an air that would soon become familiar whenever he wished to prove doctors, typewriters or batsmen wrong, a kind of grizzly incredulity.

Hughes was named twelfth man. Twelfth man in those days was more like a butler than a professional cricketer. Bosses’ instructions were to be relayed, sweat-drenched gloves replaced, team-mates’ peskiest whims respected. But as Western Australia’s fieldsmen emerged from a hot morning’s toil, their endeavour blunted by openers Woodcock and Sincock, Hughes contented himself with organising a few cold drinks. He wandered off. Twelfth man was usually the last to be seated when the host and visiting players slumped round the same boxy lunchroom. Not Kim. He was one of the first.

‘Where’s the fuckin’ twelfth man?’ growled Lillee, bursting through the lunchroom door. ‘Come and do your fuckin’ job.’ Lillee flung back the door behind him.

That’s how it was, the first time Kim and Dennis were on the same team. This week in Sydney, though neither knew it just yet, was to be the last. Kim was weeks away from his thirtieth birthday. He had hung on to his teenage habit of cover driving the quickest bowlers off one knee, sometimes at inopportune moments, then loudly congratulating himself on his own ingenuity. ‘Shot, Claggy! That’s four on any ground in the world.’

Before an innings, he liked making outlandish predictions. ‘Today,’ he’d exclaim, ‘I’m going to hit two hundred before lunch.’ Mostly his team-mates laughed. They found it endearing. ‘That’s Kim,’ they would say. Sometimes some of them, the older and more experienced ones, would get a bit annoyed.

Over breakfast in Melbourne, his predecessor as Australian captain confided to him that most players hankered after a new leader. Over dinner in Perth, a senior board man advanced the notion that he give up the captaincy for the good of his batting. Four others, all friends, said he had it in him to be the next Viv Richards; but he could not possibly, they hissed, be the next Viv and be captain. One of those four well-meaning friends was fast bowler Wayne Clark. ‘If he’d just played cricket,’ says Clark, ‘just got on and played cricket, he would have gone down in the annals of fucking cricket history.’

Kim dwelt on this, resigned, slept on it, then cancelled his resignation. His vice-captain reckoned him ‘very naive’ and ‘liable to do silly things’. The stand-in vice-captain recommended Kim do an apprenticeship under ‘somebody everybody respects’. And as he tapped once more on the popping crease it was as if his cracked and scrubby SS Jumbo, so dotted in red cherry-marks that they blotted out the bottom S of the maker’s logo, was a barometer of his relationship with Australian cricket’s most powerful men.

But this was New Year’s Day, 1984, and great prospects lay in front of Kimberley John Hughes. Tomorrow the Fifth Test against Pakistan would begin. On the second evening Greg Chappell would announce that his wife Judy’s long-standing wish—for him to have enough spare time to sweep the leaves off the family tennis court—was about to come true. The next morning Lillee would follow Chappell into retirement. Then Rodney Marsh would let slip his unavailability for the forthcoming Caribbean trip, and spectators knew they were seeing ‘Bacchus’ devour outside edges, like a bushy-lipped Pac-Man in pads, for the last time in Tests.

After five days Wayne Phillips rolled his wrists over an Azeem Hafeez half-volley and yanked out one stump in celebration. Kim Hughes’s Australians had beaten Imran Khan’s men 2–0. It was his first series triumph in four attempts as leader. And the three revered legends who had done more than most to make life tricky for him were suddenly out of the picture. Just like that.

Think of it not as the end of an old era, Kim would say in the days to come, but the dawning of a new one. First things first, though. Somehow he had to get through this net session.

•••••

MURRAY BENNETT almost had to remove his dark-tinted spectacles and rub his eyes to believe what he was seeing. The specs gave him the appearance of someone more likely to drive taxis to the airport than batsmen to distraction courtesy of a handily disguised arm ball and some delicate pace variations. But the specs were working fine. A week had blown by since Bennett’s unexpected call-up to the squad. Now he found himself bowling in the same net as Dennis Lillee. Except that the moment Kim Hughes arrived for a hit, Lillee stalked away in the opposite direction. Previously he’d been jogging in and unloading off a few yards. Now he crouched far away, roughly two-thirds the length of his full run-up, ball in hand.

Lillee’s first ball spat off the pitch and zoomed at Kim’s head. So did the second. ‘I was thinking: Jesus!’ Bennett recalls. ‘I couldn’t believe it. The two blokes were on the same side. And Lillee seemed to be taking some cheap shots at him.’

Lillee continued. His third and fourth deliveries put his own toes in graver peril than Kim’s. ‘Every ball was short,’ says Bennett. ‘I thought, there’s something missing here.’ Bennett peered around at faces familiar from years of studying them on TV. A few little smiles, maybe. Otherwise nobody seemed to notice. ‘I guess I was a bit disgusted. Lillee was a great hero of anyone who had grown up in the game and I was just getting to know him on a personal level. For a bloke of his stature I thought it was way out of line. I didn’t think it was very impressive at all. I was thinking to myself, I’m glad I’m not batting in here.’

If Bennett’s new team-mates appeared blasé, that was only logical. They had seen it before—not twice or three times, but often. Geoff Lawson was still wincing at the memory of the previous summer’s Perth Test against Bob Willis’s Englishmen. ‘Lillee nearly broke Kim’s arm,’ says Lawson. ‘Just ran in and bowled lightning at him in the nets and Kim had to go off for an X-ray, as I recall. Got hit in the forearm the day before the Ashes started.’

The summer before that, Graeme Wood felt the same mixture of panic and unease pollute an Australian net session. Again it was Test match eve: Pakistan at the Gabba. ‘Oh, you know,’ says Wood, ‘again it was on. I remember Kim getting hit, got him right near the elbow, sort of, the forearm. He had to get ice on it and there was doubt over whether he’d play. Not the great morale booster you need before a Test. Because it’s such a bony area, there was concern.’

Other times Wood, a mate of Hughes and Lillee, would joke that he himself was safe in the nets because he and Lillee played for the same club side, Melville. That didn’t mean Lillee laid off him completely. ‘But you could tell,’ says Wood, ‘that he wasn’t trying to knock my head off.’

Craig Serjeant, former Australian vice-captain, tells of one net session where Lillee let fly his customary bouncer at Kim, followed through, retrieved the ball and looked remorseful.

‘Sorry.’

‘Oh, that’s OK.’

‘Sorry I didn’t fuckin’ hit ya.’

Invariably, though, not a word would be uttered. And Kim would never flinch or grouse. Instead he hooked or ducked or fended away. It made for exhilarating private viewing. During some of the drearier early-eighties interludes, while Kiwi workhorses chugged into seabreezes and subcontinental off-spinners whizzed down their darts, the real spectacle unfolded out of match hours and out of sight. Fiercest were the duels on the WACA practice pitches. There, the bounce was steep—and therefore lethal—but also true, so Kim could trust the ball’s trajectory and back himself to hook. Sometimes, say team-mates, the green nets could not seal them in. Lillee would drop short, Kim would skip on to the back foot and top-edged skyers would fizz out of the ground, beyond Nelson Crescent and orbit Gloucester Park trotting track.

The scene at the SCG on New Year’s Day 1984 was not dissimilar. ‘Kim was fantastic,’ Bennett remembers. ‘He hooked them off his nose or ducked. Then he picked up the ball, threw it back to Dennis and didn’t say a word.’

Bennett was not the only newcomer feeling overjoyed to be there yet slightly puzzled. John Maguire debuted alongside Greg Matthews in Melbourne the week before. Two less alike joint debutants Australia has never known. Medium pacer Maguire was gentle, modest and superfit, a Kangaroo Point cartographer. Allrounder Matthews strummed air guitar between deliveries and wore calf-high black suede boots to the team’s pre-Test gathering. He’d happily represent Australia for nothing, he proclaimed, so Greg Chappell ripped up Matthews’s paycheque as penance. In Sydney, the dressing-room telephone lingered in Maguire’s mind. Some players wrapped it in red electrical tape, dubbed it the rebel-tour hotline and announced: ‘We’re waiting for the call from South Africa.’

‘You know when you’re in a side that bonds well together and hangs around together and practises together and everyone encourages each other,’ says Maguire. ‘It’s an intangible thing. But you know when it’s not there.’

After surviving his net ordeal Kim romped through the match itself with distinction. Chappell, Lillee and Marsh set about storming the few statistical fortresses they hadn’t breached already. Chappell’s 120th Test catch equalled Colin Cowdrey’s world record, and Kim hugged him tight from the side, fingers beating out a delighted drumbeat on Chappell’s ribcage. When Chappell turned and scampered a third overthrow to sweep past Don Bradman’s 6996-run pedestal, Kim was up the other end. He switched course, veered diagonally at Chappell and fisted the air as they crossed. Unwitting latecomers might have wondered which one had just eclipsed The Don. Chappell looked merely relieved, shoulders slumped, forehead soaked, like he had stepped out of a mine shaft and into a sunshower. Kim’s bliss as he clapped his bat knew no bounds.

Chappell and Lillee were the last ones to leave the dressing room on their final morning. They had been all summer even though administrators, suspecting mutiny, had urged them to please walk out with everybody else. Kim hustled his men into two ragged rows. The retirees were applauded on to the field through a guard of honour. It is possible that Kim resented Lillee for taking potshots at his captain’s head during his last full-length net session as an Australian Test cricketer. But the grudge, if it existed, was buried in the pit of Kim’s kitbag.

He carried himself with dignity and authority. He batted with his old daredevilry. Feet propelled him so speedily to the pitch of Abdul Qadir’s insidious turners that it hardly mattered if he wasn’t sure which way they were turning. Out for 76, his average over fourteen months stood at 65. That was better, quite a bit better, than Viv Richards. Who now reckoned him too brash, too impetuous, too immature, too cocky, too silly, too curly haired?

And who doubted his right to be captain? He had been thinking about the job since he was fourteen, not aimlessly like other fourteen-year-olds think about it, but as a realistic possibility, almost a probability, maybe even a certainty. Every Sunday morning, winter and summer, he and a mild-mannered young swing bowler named Graeme Porter would frequent one of three local parks and chuck balls at each other. Every second Sunday or so, their coach Frank Parry would say to the boy Hughes: ‘Not only will you play—you’ll captain Australia.’

That free-spirited 76 in Sydney was the last time he raised his bat to the crowd for a Test half-century. By the end of 1984, year of great prospects, he was out of the team.

•••••

AUSTRALIA’S CRICKET CAPTAINS, the late Ray Robinson taught us, have been plumbers, graziers, dentists, whisky agents, crime reporters, letter sorters, boot sellers, handicappers, shopkeepers, postmen. They have also been authors. Their book titles—Captain’s Story, A Captain’s Year, Captain’s Diary, Walking to Victory—have usually been suggestive of the content, straightforward snapshots of seemingly inevitable glory. Kim Hughes’s glories were many and multifaceted. But little about them was inevitable and far too many of them were overshadowed by disasters, disasters which were also many and multifaceted, and which were almost too terrible to mention, let alone write about.

Until now they never have been. Among regular captains of the last half a century, only Kim Hughes has not had a book written by or about him. If he is remembered at all, it is as the captain who cried when he quit at a press conference. All else has lain smothered under the ordinariness of a 37.41 batting average. Yet what a story beckons—the story of a country boy who would leap three, four, five steps down the pitch to bowlers fast or slow. He would go along with the umpire’s decision. He would wear a cap not a helmet. He would try to hit the ball out of the ground when within reach of a hundred because this put smiles on people’s faces, even if it meant getting out in the nineties, as it often did.

‘To create some memories for myself and for other people’—that was always the boy’s first aim. Only after accomplishing that would he set his mind to scoring as many runs as he possibly could. This is the reverse of nearly every other cricketer’s thinking. Runs and wickets are the thing, smiles and memories happy accidents.

Despite this, and because of this, Kim hit 117 and 84 against England in the Lord’s Centenary Test of 1980. For five days no ball was too wide to square cut, no medium pacer too respectable to be hoicked. A year later, Boxing Day 1981, he bludgeoned 100 not out against West Indies in Melbourne when no one else got past 21. He did it against history’s meanest speed quartet, on a pitch that alternately skidded and popped, in circumstances that demanded he pre-empt where the ball might land because standing back and waiting for the bowler was tantamount to surrender. It is possible to conceive Don Bradman, acme of batting foolproofness, playing one of these innings. It is hard to imagine any man—except maybe Stan McCabe, another son of the Australian bush—playing all three.

‘I’ve always had enough faith in myself to be different,’ the boy once said. ‘If I wasn’t a cricketer I’d be something like a deep-sea diver.’ What he meant was the idea of him being anything else was crazy. Cricket’s values, its traditions, ran through him. He was born to cricket. He belonged in cricket. But belonging in cricket, which is a culture, is different from belonging in the Australian cricket team, which is more like a club.

Kim went from captain of the club to out of the club in five weeks of elongated anguish at the end of 1984. Conspiracy theories abounded. What raw material this unwritten book promised. What riches. It even ended in tears. For a short, tantalising while the Kim Hughes story was cricket’s block-buster-in-waiting. ‘If he lets rip like he once did those cover drives, his book could be not only a real tear-jerker but wickedly and condemningly revealing,’ noted Frank Keating, grandmaster of British sportswriting, sitting poolside in Arabia during Kim’s last official Australian trip. At the subsequent press conference revealing his leadership of a rebel tour to apartheid South Africa, Kim declined to field questions. ‘Like most cricketers I have a book to write,’ he explained. ‘And I’m sure you’ll all want to read it.’

Sportsnight-goers at a Geelong sports store were warned of imminent skulduggery revelations in a forthcoming autobiography. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the book was ‘a few months’ away. A few months came and went. By October 1985 publication had been postponed a year. ‘I really feel everything will come out in my book, that things will come home to roost.’

Cricket moved on. Allan Border’s Australians won the 1987 World Cup. Kim’s book still hadn’t materialised. ‘Those days seem a long time ago. I’ll write a book about them one day and it will certainly be very interesting.’ That was in November 1987. The idea slid away again.

In 2006 I rang Kim. Yes, he’d read the letter I sent. ‘No, I’m not interested in writing a book,’ he said flatly. ‘I’m fifty-two and I don’t need the aggro. It would stir up a lot of people.’

But I had no desire to ghost his life and times. I said I wanted to write an unairbrushed tale of Australian cricket in the Hughes mini-era, told through his experiences, encompassing many voices. I also said there was more to him than a 37.41 average and history should be set aright. He sounded like he was in a hurry.

Five months later, we talked again. He wasn’t unhappy to hear from me. But he repeated that he did not want to be the one to ‘stir things up’. He had no real objection to me writing it. He just didn’t want to be involved. Any book about him would mean big names and controversy and reporters ringing him up all over again. If he were ever going to write his autobiography it would have been when Peter McFarline, the old Age cricket correspondent, was alive to help. He said McFarline understood the personalities. When McFarline died in 2002, the chance was gone. And now he had ‘turned the other cheek’. He would ask his lawyer, business adviser and family not to speak to me. Others could if they wanted to.

Others did: friends, team-mates, coaches, teachers, officials, close observers. Almost all mentioned Kim’s niceness. He addresses people by their first name. He loves being around and encouraging children. He likes being people’s best friend. In our second phone conversation, six and a half minutes of me trying to sweet-talk him round, he didn’t hang up and he said over and over, warmly, ‘It’s no slight against you.’

Sometimes affection for Kim came from unlikely sources. ‘I don’t say this about a lot of blokes,’ says Greg Chappell, ‘but I love Kim Hughes. I can tell you that now. I admire what he’s been through because my life’s been very easy compared with Kim Hughes’s life, and I think most of us could say that.’

Kim and Dennis and Rod all get along now, people say. You see them out having beers together. Several people add, in swallowed whispers: ‘If I was Kim I wouldn’t go out drinking with them. Not after everything . . .’

I remembered Kim’s own words: that he had ‘turned the other cheek’. How much pressure had he been under? How much hurt was there? Why did he never write that book? Was it because he finally felt part of the club—and was afraid of being expelled again?

Late in my research, I discovered a tape of a speech Kim gave at the Australian Cricket Society’s annual dinner in August 1990. ‘Yes, I’ve thought about writing a book,’ he said that night. ‘It would be a bestseller. I would make a lot of money. But I really don’t feel deep down that I’d be proud about it. Maybe I’m going to take those things to my grave. Maybe too many other people have made a mistake of getting rid of the old basic values that what was said within the changerooms should stay in the changerooms. Those basics went out the door for a while and people made a lot of money. But Australian cricket paid a price.’

I knew I did not want to ‘stir things up’ for him too much. I also sensed, more strongly than ever, that you cannot understand Australian cricket in the 1980s, you cannot understand the men who ran the club—the Chappell brothers, Lillee, Marsh—unless you understand what happened to Kim Hughes.

And to understand Kim Hughes, the first thing you have to appreciate is that here was a batsman who had every shot in the book, which can sometimes be a problem, because when you have all the shots you want to play them. And that can get you in trouble.

ONE

‘Let Him Stew’

DENNIS LILLEE IS concise with his words and passionate about the Australian XI. Both qualities were evident a year after his retirement when he was asked about his legacy. Would he, wondered the journalist from Australian Cricket, go down as ‘a Ned Kelly anti-hero’ or ‘a pure sporting legend in the Bradman mould’?

‘If I am remembered,’ replied Lillee, ‘as someone who gave a hundred per cent at all times, I don’t care what else I am remembered for.’ In the two decades since, his legend taller and leg-cutter retrospectively deadlier with every passing summer, he has got his wish. Getting what he wishes is a third characteristic of Lillee’s.

His wicketkeeping pal Rodney Marsh can be even more concise. Sometimes Marsh’s concision turns into gruffness. ‘The team is the thing and to devote yourself anything less than one hundred per cent to that team is tantamount to treason,’ Marsh once wrote. Should anyone dare accuse him otherwise—‘I’d like to meet the idiot and personally shove the proposition down his throat or up some other orifice.’

Giving a hundred per cent is the most quoted yet least quantifiable of cricket’s prefabricated parrot phrases. It is almost meaningless—a hundred per cent of what?—and was junked anew by Matthew Hayden’s twenty-first century pledge of ‘one billion per cent’ support for Ricky Ponting. It is also immeasurable. The sport of run rates, over rates, strike rates and economy rates knows no such thing as effort rate. All anyone can do is watch a game unfold and interpret what they see. Between May and September of 1981, when Australia toured England, several people saw a lot of things they had trouble interpreting.

•••••

AUSTRALIA’S NEW CAPTAIN was interviewed by John Wiseman on Channel Ten’s Eyewitness News the day after his appointment. Kim’s hair was damp and combed straight—no curls—but as he licked dry lips and swiped Perth’s flies out of his face he looked more boyish than ever.

‘Kim, first of all congratulations. What do you think of some of this morning’s criticism?’

‘Well I don’t know who’s criticising me at all, John, but I suppose one in my position isn’t going to please everybody.’

Kim had led Australian Test teams before. That was during the World Series Cricket days when the country’s three dozen finest were otherwise engaged as Kerry Packer’s so-called circus act. This time the tidings were auspicious, theoretically: a full-strength squad with a winning chance. Theory was one thing. In reality, Western Australia’s battle-hardened Bruces—Laird and Yardley—had been left out. Human dynamite sticks Jeff Thomson and Len Pascoe were missing. ‘I always thought selectors were idiots,’ reasoned Thommo. ‘Now I know it.’ Record crowds descended on the bar of the Dungog Bowls Club. Not since 1964 had local sweetheart Doug Walters been overlooked for an Ashes trip. ‘We would listen on the wireless till 3 a.m. when Doug was playing,’ grumbled one irate Dungogian. ‘When he hit a four we’d celebrate by opening a cold one. Maybe we’re biased but, blimey, it’s a bit crook.’

Heading the unlikelier inclusions in Australia’s 1981 Ashes squad was Graeme Beard. He’d added folded-finger off-breaks to his repertoire two years earlier when his slow-mediums kept thudding into Tooheys advertising boards at a speed considerably zippier than slow-medium. Youngest of the Chappell trinity, Trevor, was also England-bound. ‘The first Australian cricketer to have won a major berth on the strength of his brilliant fielding,’ commented McFarline in the Age.

Alas, Trevor was a like-for-not-at-all-like swap with Greg. Greg ruled himself out to fellow selectors on a Tuesday. The squad—minus a captain—was announced on the Wednesday. A public explanation was forthcoming, for a fee, on a Thursday-night TV special, Greg Chappell: Covers Off. He revealed that his son Stephen no longer knew whether Greg Chappell was his absent father, a famous cricketer, or both. Business interests, including an insurance company, were mounting too. ‘March, April, May and in particular June,’ he elaborated, ‘are vital to the success of the venture.’

On the Friday, Kim was named captain. A newspaperman gave him the good news before anyone from the board did.

Where was Lillee hiding? That was an eventful week’s biggest mystery. Six months earlier he and Marsh had each rejected the Western Australian vice-captaincy under Kim. Lillee’s name was one of sixteen on the teamsheet for England. But how much was that piece of paper worth? Scuttlebutt crisscrossed the continent from east to west and back again. Finally Perth journalist Ken Casellas found Lillee in the riverside clubrooms of Tompkins Park. It was Saturday night. Lillee was puffed from twenty-five knackering overs for Melville. He was drinking his own version of a shandy—one gulp out of a can of beer, one gulp of lemonade—but there was nothing bubbly about his demeanour. ‘I’ve got an unlisted phone number and it’s been changed a few times. Still I get calls day and night from all over the world from people wanting to know whether I’m going on tour. All I want to say is I’m happy the season is over.’ The mystery deepened.

Kim celebrated his appointment by popping a couple of balls out of the park in his next innings, an unbeaten 156 in a first-grade semi-final. At the ABC Sportsman of the Year awards, he was asked if he tended to decide on a stroke before the ball was bowled. Confounding the laws of reliable run gathering, Kim answered: ‘Yes.’ Knowledgeable sorts watching in their living rooms were appalled. But vindication arrived a week before the team’s departure when he was listed among Wisden’s five cricketers of the year. Inclusion in Wisden’s famous five traditionally recognises a season’s haystack of runs or wickets. Kim was picked for his two celestial Centenary Test knocks. Anyone who reckoned it impossible to premeditate deliveries and prosper needed only to skim the highlights tape.

The thought of returning to England was sweet. It was tantalising enough for Lillee to decide to go too, although he and Marsh were permitted to skip the pre-tour detour to Sri Lanka. The Australians arrived on day one of the monsoon season. Pitches were custom-built for Sri Lanka’s finger-spinning trio. Power was switched off every morning and evening, for the system was hydro-electric and there was a water shortage. On the field, too, it was as if Australia were playing in darkness. Outclassed in the drawn four-dayer, they sneaked the skimpiest of victories in the unofficial limited-overs series, perverse preparation for an English spring.

Really, the twelve-day stopover was a fact-finding mission on behalf of board delegates unsure which way to vote on Sri Lanka’s bid for Test status. Australian officials were reportedly seen photographing stadium toilets as evidence for the ‘no’ case. ‘Come on, Aussies, come off it,’ pleaded a local newspaper. But all four games were sellouts. Sri Lankan Testhood followed months later. And Kim had not a bad word for the place, the toilets, the tour, or the administrators who devised it. He was equal to the diplomatic challenge posed by one of Rodney Hogg’s eccentric contributions to Australian touring folklore. Riled by humidity and his inability to prick a ballooning middle-order partnership, Hogg marked a cross between his eyes and nearly decapitated Ranjan Madugalle with a head-high full toss. The captain strode imperiously across from mid-on: ‘That’s not on, Rodney.’

England was three-jumper territory. Kim acclaimed the opening net session at Lord’s the best first-day workout of any tour he’d been on. This cocktail of good cheer, naivety and overstatement would become a trademark of his public pronouncements, one that bugged some team-mates. But not yet. At Arundel Castle he was out to his first ball of the tour, an Intikhab Alam top-spinner grubbering into his boot. His humour survived. Invited by the ground manager in Swansea to nominate a time for practice, Kim grinned. ‘Six o’clock in the morning—the only time it doesn’t rain in this country.’ Drizzle, sleet, frost and murk gave Kim ample chance to polish his introductory note for the Test brochure:

As I write this message I know that I am back in England. Once again we are stuck inside the dressing room watching rain stream down the windows. However, I am certain this year’s full tour of England will prove to be one of the most exciting in the long history of England versus Australia contests . . . I hope you enjoy watching the cricket and also that I will be able to say ‘hello’ to as many of you as possible.

Kim’s ‘hello, everyone’ policy extended to travelling Australian scribes. ‘We want you to feel part of the team,’ he told them. He enquired after their welfare over breakfast and hosted candid off-the-record briefings over drinks. ‘Team-mates are singing his praises daily and lauding the great team spirit,’ reported Alan ‘Sheff’ Shiell. ‘Australian pressmen will not tolerate a bad word about Hughes the man.’ English broadsheet writers stepped the pro-Kim hoopla up several more adjectives. Some felt they’d been shown few courtesies during the furry-bellied Chappell dynasty. They appreciated Kim’s plain-speaking eloquence, his insistence that nothing was too bothersome. ‘I hope he becomes what he deserves to be—the most popular captain since Lindsay Hassett,’ wrote Robin Marlar in the Sunday Times. Frank Keating found fault only with the patchy stubble clinging to Kim’s chin: ‘His clean boy scout’s face somehow goes better with the sparkling innocence of his batsmanship. Pulled this way and that by photographers, fringers, high commissioners, low commissioners, book commissioners and hall-porter commissioners, he never stopped being softly obliging.’

Kim’s next coup was to oversee Australia’s maiden triumph in a one-day series in England. Shivering and rusty, they lost at Lord’s then levelled at Edgbaston, where England needed six off the last over and Lillee kept them to three. As Kim walked into the press conference, Australian journalists rose and clapped. At training before the series decider, Trevor Chappell confessed his terror of England’s middle order, which had throttled him on wickets made for his glamourless wobblers. Yes, admitted Kim, he felt a bit the same way about Trevor’s bowling. But he stuck to the plan. Chappell’s three wickets proved suffocating.

Hunches continued hatching fruitfully once the Tests started. Twice Kim called heads and chose to bowl. No Ashes captain had gambled like that before in the first two Tests of a series. Australia won at Trent Bridge and had marginally the better of a soggy Lord’s draw. At Trent Bridge, Kim kept the cordon stacked with four slips and the ball in the hand of a 25-year-old debutant with a centipede moustache. Terry Alderman’s hula-hooping outswingers knocked nine Englishmen aside. Chasing 132, Australia’s seventh-wicket pair were meandering towards victory when Kim joined Alan McGilvray and Christopher Martin-Jenkins in the Test Match Special box.

McGilvray: Weather good, perfect conditions. Now Lawson . . .

Hughes: Whewwwwsh.

McGilvray: There’s a big sigh from Kim Hughes. Yes I know how you feel. Now Dilley is on his way to Lawson, and Lawson turns it . . .

Hughes: ONE MORE.

McGilvray: One more, says Kim.

Not for a second did he disguise nerves or excitement.

McGilvray: Dilley moves away from us to bowl to Lawson. A full toss and . . .

Hughes: GOOD SHOT! FOUR! GOODY!

Kim clapped his hands and shouted advice and bellowed over the top of the two commentators.

McGilvray: Chappell, you must stay there and pick up these four runs. And Kim, if you’d like to leave anytime . . .

Hughes: Yeah, I might, ah, just wait one more ball.

A strangled titter.

McGilvray: Right, one more ball, all right.

Hughes: I might just sit in my seat.

CMJ: Terrible isn’t it, Kim?

Hughes: Ay?

CMJ: Terrible isn’t it?

Hughes: Aww, I don’t know how anybody can captain for more than a game.

That night it was possible to picture Kim Hughes, twenty-seven, captaining his country for so long as he craved. The Ashes urn had been England’s property since 1977. But the handover was nigh, surely. Several uproarious hours later at the team hotel, Marsh, Lillee and Kim were seen deep in discussion, shoulders entwined. Kim cheerfully told anyone who’d listen about how Marsh had held up a glove and halted play with Lillee poised to tear in at Willis.

‘You’ve got all the angles buggered up,’ Marsh roared.

‘Oh,’ said Kim. ‘What do you want?’

Marsh reset the field. Deep cover point was relocated twenty-five metres sideways. Two balls later Willis hit straight to him.

‘I’m hardly a captain at all,’ Kim was saying that night. ‘But Hughes, Marsh and Lillee is a bloody good captain.’

•••••

COMING UP TO the Third Test at Headingley, Australia’s coach Peter Philpott sensed Kim was in trouble. Over a beer, he voiced his worries to Marsh, the vice-captain.

‘Rodney, we’ve got to try to help him.’

‘He’s got the job,’ said Marsh. ‘He’s a big boy. Let him stew in it.’

Marsh’s words still grate in Philpott’s head:

It wasn’t a pleasant relationship between Kim and the other two. They thought he was a soft boy. They were two hard men and they didn’t have much respect for him. They respected his batting but not his captaincy or him as a human being. I don’t think they respected Kim as a man. They didn’t hide that. In fact they allowed themselves at times to do just the opposite. You couldn’t help but watch and be disappointed at the way they threw the boy to the wolves—threw him to the wolves and didn’t throw out a line to help him.

Philpott found Kim faintly immature. ‘I think Rodney and Dennis saw him as a kind of little golden boy.’ Captaincy was the main volcano of contention. Dennis thought Rodney should be in charge. Rodney thought Rodney should be in charge. It reminded Philpott—up to a point—of Australia’s 1957–58 visit to South Africa. A freckle-faced pharmacist still living with his parents led that tour. ‘Neil Harvey and Richie Benaud would have been flabbergasted when Ian Craig was appointed captain over them,’ says Philpott. ‘But they gave him total support. Ian was only a kid and they helped greatly. That didn’t happen in 1981.’

With Australia one Test up, the cracks were undetectable to outsiders. Esso scholar Carl Rackemann was borrowed from Surrey’s 2nd XI to fortify Australia’s sniffling pace attack against Warwickshire. Thirty-six more thrilling hours he’d never known: ‘My impression of the dressing room was that everything was pretty positive, pretty good.’ Similarly, the reporters who rained a standing ovation upon Kim after the second one-dayer had no inkling of the bloodletting behind slammed doors. In the first match Australia bowled sloppily, fielded scruffily, and Philpott told them so. Second time round they were a team rejuvenated. Henry Blofeld’s report in the Australian concluded: ‘For me, Peter Philpott and Geoff Lawson were the men of the match.’

Blofeld’s article whipped round the dressing room. Fair enough, thought the players from New South Wales, Philpott’s home state. Bulldust, chorused the rest. ‘The Western Australians, they were livid,’ Philpott remembers. ‘Kimberley was very upset. And the lines were clearly defined.’ To suggest any correlation between Philpott’s salvo and the team’s salvation was tripe, the players huffed. And if there was . . . Well, if that was the case then the little man in the tracksuit was plainly exceeding his brief.

When Marsh and Lillee addressed Kim by his nickname, something about the way croaky voices draped over the first syllable—‘Claaaaa-gee’—made others think of grown men patting a boy on the head. Body language—folded arms, rolling eyes—often spoke loudest. Pinpointing what ailed this team wasn’t always easy. It was a feeling people got. Lawson believes Lillee and Marsh spent ‘nearly every waking hour’ undermining Kim. ‘I wouldn’t have thought that,’ counters Wood. ‘We were playing very well.’ For Graeme Beard: ‘We were a bunch of fellas playing cricket for Australia and it was fabulous. I got on well with all the blokes.’

Was it a united side? Beard goes quiet.

‘Well. Probably not. A difficult situation.’

And that’s all you’ll say?

‘Mmmm,’ says Beard. ‘Well. Yeah.’

The cracks were small in those early days on tour but they were there. And they were not like cracks in a vase that could be sealed with putty. These cracks were like a run in a stocking. They were only going to get bigger. They opened up the moment the team left for Sri Lanka minus Marsh and Lillee. ‘That was very significant,’ says Philpott. ‘In the bonding period, they weren’t there.’

Philpott planned to build unity through practice, then more practice. But the Sri Lankan leg was hectic. When time did allow for nets, it was too hot to move or too wet to try. Then they hit England. Philpott recalls:

For six weeks we sat in front of the fire and froze. And in that situation the unpleasantness tended to grow. The infection spread. It all made it harder for Kimberley, so much harder. I don’t think he was up to handling it. Not many blokes would be. If they’d made Allan Border captain he would have been in much the same position. Rodney and Dennis wouldn’t have been so anti-AB, but they wouldn’t have sup- ported him greatly because Rodney still would have thought he should have been captaining.

Marsh and Lillee departed eleven days late. Marsh’s knees, creaking from years of bending, jolting and fetching, the wicketkeeper’s daily lot, appreciated the rest. Lillee had a sinus-clearing operation and deemed Sri Lanka an infection risk. His strategy backfired. He sweated away his first three weeks in a north London hospital’s isolation ward. Team-mates donned face masks to visit him. He’d picked up viral pneumonia on the journey with Marsh, or perhaps from his son, who had a chest cold. Either way, chances were his health would have been tiptop had he flown with everyone else, although everyone else probably didn’t mention this to Lillee, not even from behind face masks.

Defying medical advice, Lillee played and bowled manfully. Exhausted, he lolled in the outfield between deliveries versus Middlesex. Some observers sensed a sit-down protest against Australia’s underperforming batsmen. Admonished by Kim and manager Fred Bennett, Lillee’s reply was true to character: ‘Have you ever seen me let down Australia in a Test match?’

The bowlers had reason to quibble. Dirk Wellham’s 135 at Northampton on 13 July was the first first-class hundred—two months into the tour. Not since 8 September 1880, and Billy Murdoch’s 153 against England, had Australians found three figures so elusive so deep into an English summertime. Most dismaying was the captain’s form. A 61 at Canterbury, where he drove Bob Woolmer over a refreshments tent, was his only fifty in twenty innings. On seaming wickets he was tiptoeing negligently across the crease and getting suckered lbw. At Lord’s for the Second Test, he and Alan McGilvray discussed England’s penurious off-spinner John Emburey.

‘Watch this fellow, Kim.’

‘He can’t bowl. I’ll take the mickey out of him.’

‘Well, I think he can bowl a bit. I’d be wary of him if I were you.’

Square cutting the seamers thrillingly, Kim skipped to 42. Emburey limbered up. Whether his third ball was flat or tossed up no one truly knows, so prematurely did Kim scurry down, as if determined to shovel McGilvray a catch in the commentary box. He didn’t middle it. Mid-off caught it.

So often it ended like this. First ball of a new spell. Two minutes before drinks. Third ball after lunch. Last over of the day. It happened too often to be slack concentration. Nor could it be so simple as the reverse: that he was concentrating too hard. It was as if he was twisting between extremes, him and them, between the urge to entertain and the need to consolidate, listening to his instincts but unable to hush the voices all around, believing the whole time that cricket should be a game, but if it was a game did that mean entertaining was the thing or was winning the thing, and when the tempo was raised by a break in play or change in bowling the buzzing in his head got so loud that something had to explode. It had always exasperated team-mates. Now he was captain and still doing it.

Wellham, more compact and elegant than his reputation for stickability suggested, was mooted as a possible twelfth man at Headingley, some promotion for a novice of four Sheffield Shield games. Two days beforehand he was bedridden with flu. Mooching around the nets would only make him sicker. So he left a message and snoozed all day. Upon stirring, Wellham found it had cost him his chance. ‘I was a bit annoyed. I supposedly had a black mark. But I was new. They didn’t know me so they didn’t know whether I was sick or not. I guess nobody asked.’

More unsettling was the aftermath of the Lancashire game at Old Trafford. Wellham persevered through gloomy light—‘the first time I saw Michael Holding in real life’—for 19. In the showers afterwards he felt the hot spray of his captain’s urine. It was no big surprise. Wellham had been warned about Kim’s shower-time habit after a few drinks of unburdening himself over the nearest bystander. But nor was it pleasant. ‘Just schoolboy humour,’ Wellham recalls. ‘I wasn’t thrilled. That’s OK. It was a juvenile bit of fun. You know, a party trick. I thought it was silly but I thought he was a much better player than I was.’

The trick won Kim few laughs. ‘Dennis and Rodney would have thought that was absolutely inappropriate,’ says Wellham. ‘They would have thought that was more ammunition.’ Wellham’s response was to stay under that shower and scrub himself clean. ‘I thought it was a silly thing for the Australian captain to do. But that was Kim, part of his make-up, part of his reputation, a trick up the armoury.’

Winning has a cohesive effect on teams. Piddling issues drain away. In the Third Test at Headingley, on a wicket jagging every which way but predictably, John Dyson ranked his steadfast 102 the innings of his life. Kim batted four and a half hours, a man in a straitjacket, intent on showing neither extravagance nor weakness. On 89 he was clobbered in the groin. He afforded himself the briefest of convalescences—and got out next ball. He declared at 9–401. ‘Four hundred,’ said Kim, ‘is worth a thousand on this pitch.’

England tumbled for 174. Following on, their seventh wicket fell for 135, lurching towards a 2–0 series scoreline. ‘At seven down,’ says Beard, ‘Steve Rixon and I put the champagne bottles in the bath, ready to lay ice over them.’

•••••

ALL THINGS GOOD, UGLY and illusory about this Australian team were contained in Peter Willey’s dismissal. Gradually, Kim became aware of Willey’s delight in stepping away and skimming the ball over gully. Kim switched Dyson from the slips to a deeper fly slip. Lillee advanced. Willey cut. It was too close for the stroke; arms got tucked up; the ball soared. Dyson froze so still a butterfly could have landed on his shoe. The ball floated into Dyson’s chest. ‘Superb captaincy,’ beamed Richie Benaud in the commentary box. ‘One of the best pieces of tactical thinking I’ve seen in a long time.’ England skipper Mike Brearley agreed. ‘Such immediate rewards for intelligent and inventive captaincy,’ he wrote, ‘are rare.’

Benaud and Brearley were alert and astute but not in this instance all-seeing. They missed Lillee requesting a fly slip the moment Willey arrived. No, said Kim. The ball sailed where fly slip would have been. The protagonists mumbled their way through the same rough dialogue.

Can I have one?

You may not.

Sheesh. There it goes again.

The second time it happened, Lillee clamped hands on hips. Marsh wandered over to yarn with the captain. How about a fly slip? The captain gave in. Willey got out. The celebrations over, Kim and Lillee walked the long hike back to the top of his run-up. Never were they closer together than two metres. Both were silent. Kim crept backwards while polishing the ball on his pants. Lillee faced forwards. Neither looked in the same direction or at each other. Eventually Lillee half turned, still walking, and glared at the ball, implying ‘give it here’. They reached the top. Kim shook Lillee’s hand—a gesture Lillee did not invite or reciprocate—and passed him the ball.

Willey’s downfall brought in Ian Botham, playing his first Test since Brearley succeeded him as captain. In his last outing, at Lord’s, Botham slithered through the old white gate after a pair of noughts while MCC members all around him avoided eye contact. But the harried look in his face had vanished. He was bearded and carefree. He off-drove classically, edged a couple over fielders’ heads, then welcomed incoming No. 9 Graham Dilley: ‘Let’s give it some humpty.’

Minutes before this, Lillee bet £10 on Australia losing. Ladbrokes’ odds were 500–1. Only a mug would let those odds go cold. Marsh, initially reluctant, punted £5. ‘That bloody bet. Had Greg been captain they’d never have done it,’ believes Adrian McGregor, Chappell’s biographer. ‘Or if they did it would be a big joke and Greg wouldn’t have been happy. He’d have thought it disloyal.’

Nobody thought much at all of it at the time. Nobody considered defeat possible. England were three wickets from despondency and 92 runs shy just of making Australia bat again. Botham had already checked out of the hotel. His swings, misses and top-edges began as defeatism and quickly became something else. Left-hander Dilley, blond-haired and blue-helmeted, clouted crooked deliveries through cover like a Graeme Pollock doppelganger. Botham was either driving majestically or pull-slogging flatfooted. One ball caught the splice and zoomed for the stratosphere. Kim jogged and fetched it, frowning, off a boy in a margarine anorak.

After Dilley came Chris Old. Old studied Lillee, Marsh, Alderman, Kim—‘all signalling different fielders to go in different positions’. Botham stuffed England’s tuckerbag with 117 runs in partnership with Dilley, then 67 more with Old. That evening, dapper stumper Bob Taylor ducked into the Australian rooms with bats under his arm for autographing. ‘Fuck off with your fucking bats,’ he was advised.

Irritation had set in. But not despair. At breakfast, Kim and the Sydney Sun’s Frank Crook discussed the inevitability of an Australian victory and the improbability of the board reappointing Greg Chappell. ‘I don’t think they’d dare,’ said Kim. Botham ransacked 37 last runs with Willis. He bounded off—to a knighthood, ultimately—149 not out. Australian victory, no longer the only possibility, remained a formality: 130 to get.

The first over was busy. Wood clumped two leg-side boundaries and was judged caught behind when only the bowler appealed: ‘A shocker. Must have hit some footmarks.’ Dyson and Trevor Chappell travelled serenely to 1–56. Operating uphill and upbreeze, Willis threatened no one. ‘Too old for that,’ he griped to his captain. Brearley baulked at his uppity fast bowler. Five minutes later he reconsidered, offering Willis the wind and the Kirkstall Lane End.

A ball theoretically too full to endanger brain matter kicked at Chappell’s head and he parried a catch to Taylor. Enter Kim, a picture of circumspection for eight scoreless deliveries, until he went fishing outside off and his feet forgot to go with him. It was the last over before lunch. The timing may have provoked wry half-smiles. Half-smiles soon tipped upside down. Graham Yallop guided Willis from his throat into short-leg Mike Gatting’s meaty hands. ‘I can remember the panic,’ says Wellham, an interested spectator, suddenly unable to look away. ‘The game had been light-hearted and jovial. Then we hit the wall and couldn’t contain it. If you’ve got a more subdued leader, you’ve got a less attacking leader. But you might have someone better able to withstand the barrage.’ Lunch was served—and barely picked over—at 4–58.

Border failed to impede a massive Old in-ducker. Dyson hooked and gloved. Marsh hooked from outside off stump and picked out long leg. There seemed an intangible aimlessness about the batting. Bright and Lillee pulled and slashed for four commonsense overs, worth 35 runs. Willis kept banging the ball in and seeing it jump. His reward was 8–43. Nine wickets melted for 55. Australia lost by 18. Nobody quite understood how. The haunting sensation was heightened by the sight of the flop-haired Willis, his eyes vacant and lifeless, hanging loosely in their sockets, like the imperilled damsel in a Mario Bava film.

So ended history’s only Test known by a suburb and two digits: Headingley ’81. Kim’s errors have become legend, part of the mystique. Once Botham attained blast-off Kim was too slow to spot the tipping point, too gung-ho to retract his fieldsmen, too reluctant to rest Lillee or Alderman. Ray Bright dropped hints. Yet not until 8–309—174 runs later—did Kim summon Bright’s slow left-armers. Trevor Chappell maintains he wasn’t even consulted; it seems trying a part-timer either never entered Kim’s head or fell out of it very quickly. Then there was his enforcing of the follow-on, sentencing Australia to bat last on an under-watered pitch. The theories have multiplied with hindsight.

All evidence suggests Kim did fret about batting last. After winning the toss he took ten minutes and two pitch inspections, accompanied by Marsh and Lillee, to make up his mind. The follow-on was simply irresistible. Bright was Victoria’s last Test spinner until Shane Warne’s emergence. But there, resemblances end. Bright’s trajectory was generally flat, his turn measured less in inches than in figments of a batsman’s imagination. Kim did overbowl Lillee and Alderman. But he’d been successfully overbowling them for two entire Tests and three-fifths of another. Besides, his only other frontline quick, Lawson, fell over a foothole and wrenched his back.

Blaming Kim for Headingley ’81 underplays another sig- nificant factor. Luck. Botham’s 149 might rightly be considered a once-every-130-years event. How his windmill wind-ups—those that connected, those that didn’t—evaded hands and stumps so repeatedly defies rational explanation. ‘Bloody lucky innings,’ Lillee called it. ‘I expected to get him virtually every ball.’ England’s turnaround was so fast, so implausible to the fieldsmen in the middle, that it became almost an hallucinatory experience, as if they were onlookers not participants. ‘I still have nightmares about that Test,’ Wood admits. ‘All along we thought we’d win. So we didn’t question it.’ Too late, the faint prospect of defeat dawned. ‘We started thinking we should have tried something different,’ says Wood. ‘But Kim probably thought Lillee and Alderman were having great tours and eventually Botham would nick one and get out. It just didn’t happen. It kept rolling on and on and on. Horrible experience.’

Or as Lawson puts it: ‘Twenty-seven years later people still ask me what would you do differently at Headingley? Well, apart from maybe giving Ray Bright a few more overs, what else could we have done?’

Kim reached the same conclusion in minutes. Outside the pavilion, his fine words were generously acclaimed by a delirious crowd. ‘I’m proud the Australian team has been part of one of the greatest Tests of all. Of course I’m disappointed we didn’t win. But we know we gave immense enjoyment.’ Later, among reporters, good manners deserted him. ‘We didn’t do much wrong except lose.’ And Botham? ‘He is a player who wins games and the only one England have got.’ That was skipping a little too conveniently over his own team’s frailties, of both the cricket and the human kind.

•••••

WHEN PRINCE CHARLES married Diana Spencer on 29 July, Kim was not among the estimated billion watching a TV set. He had a tour to run. He glanced at the replay while unwinding in his eighth-floor room of the Albany Hotel in Birmingham, scene of the Fourth Test. The match would prove the noisiest ever played in England, reckoned the home players, as if the wedding guests had decamped from St Paul’s Cathedral and flocked to Edgbaston for the reception.

The cricket was worthy of the din. England were skittled for 189 and Australia responded with 258. Kim’s boundary-laden 47 was top score. At England physio Bernard Thomas’s garden party, he told Brearley: ‘I only hope we don’t have 130 to get again.’ England stuttered obligingly to 8–167, 98 ahead. Then Emburey and Old, a nudger and a swiper, hoisted 50 more in one of the tour’s most telling half-hours.

If Australia’s chase of 130 at Headingley reeked of aimlessness, a touch of catatonia pervaded their pursuit of 151. Border camped three and a half hours for 40, Yallop two hours for 30, Kent 68 minutes for 10. Kim’s hook stroke on 5—slammed flat and hard off one leg, his posture geometrically impeccable—summed up the man. ‘Ah,’ purred the BBC’s Mike Smith, ‘it’s a beautiful shot.’ Smith paused to admire the ball’s flight. ‘But straight down that man’s throat. A beautiful-looking stroke . . .’

Botham’s 5–1 in 28 deliveries applied the finishing gloss. Australia all out 121. Kim’s kicked-puppy demeanour inspired one of Richie Benaud’s shiniest lines: ‘Hughes there, looking like he’s just been sandbagged.’ Bob Taylor likened him to ‘a shellshocked soldier . . . Not for the first time I found myself wondering how much respect he was given by the former Packer players.’

While Kim grieved publicly, Marsh sought refuge alone in the downstairs dressing room. ‘I don’t recall the tears welling up inside,’ Marsh wrote later. ‘But suddenly I was sobbing.’ As he sat and he wept, Marsh reflected on Australia’s batsmen. Mostly he thought about Kim. ‘I thought what might have happened if Hughes had not played a stupid hook shot when the Poms had two men stationed out in the deep. Christ, a captain is supposed to lead by example.’

Trailing 1–2 when he might have led 3–0, Kim finished that night dancing on a table at Bob Willis’s benefit function. Resilience was one of Kim’s less appreciated but undying characteristics. Memorable was his conversation with Brearley: ‘I suppose me mum’ll speak to me. Reckon me dad will too. And my wife. But who else?’ Kim neither excused nor apologised for hooking. ‘I’m a natural strokeplayer. That time it didn’t come off.’

Brearley agreed with his logic. ‘And I admired his dignity.’

Kim and Lillee were unlikely holidaymakers together on the Isle of Man, house guests of racehorse mogul Robert Sangster and his socialite wife Susan. It was a kaleidoscope of race meets and casino jaunts. The series resumed in Manchester with the Ashes alive, the spirit a cropper.

•••••

THE AFTERNOON BEFORE his Test debut, Mike Whitney was handed his room key at Manchester’s Grand Hotel and told to settle in. Be back in the foyer in one hour for the press conference announcing your selection, team manager Fred Bennett instructed. Whitney went upstairs. He unlocked the door. Cricket gear was strewn everywhere. ‘There were more pills in the room than a fuckin’ pharmacy.’ He wondered who his room-mate could be. Then he realised. In the corner was a suitcase, sumptuously crafted, adorned with the letters D.K. Lillee.