5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

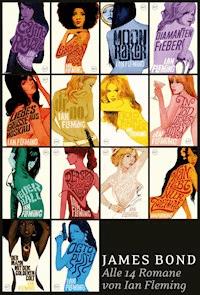

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: James Bond 007

- Sprache: Englisch

Meet James Bond, the world's most famous spy.Auric Goldfinger is the richest man in England - though his wealth can't be found in banks. He's been hoarding vast stockpiles of his namesake metal, and it's attracted the suspicion of 007's superiors at MI6. Sent to investigate, Bond uncovers an ingenious gold-smuggling scheme, as well as Goldfinger's most daring caper yet: Operation Grand Slam, a gold heist so audacious it could bring down the world economy and put the fate of the West in the hands of SMERSH. To stop Goldfinger, Bond will have to survive a showdown with the sinister millionaire's henchman, Oddjob, a tenacious karate master who can kill with one well-aimed toss of his razor-rimmed bowler hat.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 434

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Goldfinger

Goldfinger

IAN FLEMING

To my gentle Reader

William Plomer

Contents

Part OneHappenstance

1: Reflections in a Double Bourbon

2: Living It Up

3: The Man with Agoraphobia

4: Over the Barrel

5: Night Duty

6: Talk of Gold

7: Thoughts in a DB III

Part TwoCoincidence

8: All to Play For

9: The Cup and the Lip

10: Up at the Grange

11: The Odd-Job Man

12: Long Tail on a Ghost

13: If You Touch Me There . . .

14: Things That Go Thump in the Night

Part ThreeEnemy Action

15: The Pressure Room

16: The Last and the Biggest

17: Hoods’ Congress

18: Crime de la Crime

19: Secret Appendix

20: Journey into Holocaust

21: The Richest Man in History

22: The Last Trick

23: TLC Treatment

Part One

Happenstance

1

Reflections in a Double Bourbon

James Bond, with two double bourbons inside him, sat in the final departure lounge of Miami Airport and thought about life and death.

It was part of his profession to kill people. He had never liked doing it and when he had to kill he did it as well as he knew how and forgot about it. As a secret agent who held the rare Double Zero prefix – the licence to kill in the Secret Service – it was his duty to be as cool about death as a surgeon. If it happened, it happened. Regret was unprofessional – worse, it was death-watch beetle in the soul.

And yet there had been something curiously impressive about the death of the Mexican. It wasn’t that he hadn’t deserved to die. He was an evil man, a man they call in Mexico a capungo. A capungo is a bandit who will kill for as little as forty pesos, which is about twenty-five shillings – though probably he had been paid more to attempt the killing of Bond – and, from the look of him, he had been an instrument of pain and misery all his life. Yes, it had certainly been time for him to die; but when Bond had killed him, less than twenty-four hours before, life had gone out of the body so quickly, so utterly, that Bond had almost seen it come out of his mouth as it does, in the shape of a bird, in Haitian primitives.

What an extraordinary difference there was between a body full of person and a body that was empty! Now there is someone, now there is no one. This had been a Mexican with a name and an address, an employment card and perhaps a driving licence. Then something had gone out of him, out of the envelope of flesh and cheap clothes, and had left him an empty paper bag waiting for the dustcart. And the difference, the thing that had gone out of the stinking Mexican bandit, was greater than all Mexico.

Bond looked down at the weapon that had done it. The cutting edge of his right hand was red and swollen. It would soon show a bruise. Bond flexed the hand, kneading it with his left. He had been doing the same thing at intervals through the quick plane trip that had got him away. It was a painful process, but if he kept the circulation moving the hand would heal more quickly. One couldn’t tell how soon the weapon would be needed again. Cynicism gathered at the corners of Bond’s mouth.

‘National Airlines, “Airline of the Stars”, announces the departure of their flight NA106 to La Guardia Field, New York. Will all passengers please proceed to gate number seven. All aboard, please.’

The tannoy switched off with an echoing click. Bond glanced at his watch. At least another ten minutes before Transamerica would be called. He signalled to a waitress and ordered another double bourbon on the rocks. When the wide, chunky glass came, he swirled the liquor round for the ice to blunt it down and swallowed half of it. He stubbed out the butt of his cigarette and sat, his chin resting on his left hand, and gazed moodily across the twinkling tarmac to where the last half of the sun was slipping gloriously into the Gulf.

The death of the Mexican had been the finishing touch to a bad assignment, one of the worst – squalid, dangerous and without any redeeming feature except that it had got him away from headquarters.

A big man in Mexico had some poppy fields. The flowers were not for decoration. They were broken down for opium which was sold quickly and comparatively cheaply by the waiters at a small café in Mexico City called the Madre de Cacao. The Madre de Cacao had plenty of protection. If you needed opium you walked in and ordered what you wanted with your drink. You paid for your drink at the caisse and the man at the caisse told you how many noughts to add to your bill. It was an orderly commerce of no concern to anyone outside Mexico. Then, far away in England, the Government, urged on by the United Nations’ drive against drug smuggling, announced that heroin would be banned in Britain. There was alarm in Soho and also among respectable doctors who wanted to save their patients agony. Prohibition is the trigger of crime. Very soon the routine smuggling channels from China, Turkey and Italy were run almost dry by the illicit stockpiling in England. In Mexico City, a pleasant-spoken Import and Export merchant called Blackwell had a sister in England who was a heroin addict. He loved her and was sorry for her and, when she wrote that she would die if someone didn’t help, he believed that she wrote the truth and set about investigating the illicit dope traffic in Mexico. In due course, through friends and friends of friends, he got to the Madre de Cacao and on from there to the big Mexican grower. In the process, he came to know about the economics of the trade, and he decided that if he could make a fortune and at the same time help suffering humanity he had found the Secret of Life. Blackwell’s business was in fertilisers. He had a warehouse and a small plant and a staff of three for soil testing and plant research. It was easy to persuade the big Mexican that, behind this respectable front, Blackwell’s team could busy itself extracting heroin from opium. Carriage to England was swiftly arranged by the Mexican. For the equivalent of a thousand pounds a trip, every month one of the diplomatic couriers of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs carried an extra suitcase to London. The price was reasonable. The contents of the suitcase, after the Mexican had deposited it at the Victoria Station left-luggage office and had mailed the ticket to a man called Schwab, c/o Booxan-Pix Ltd, WC 1, were worth twenty thousand pounds.

Unfortunately Schwab was a bad man, unconcerned with suffering humanity. He had the idea that if American juvenile delinquents could consume millions of dollars’ worth of heroin every year, so could their Teddy boy and girl cousins. In two rooms in Pimlico, his staff watered the heroin with stomach powder and sent it on its way to the dance halls and amusement arcades.

Schwab had already made a fortune when the CID Ghost Squad got on to him. Scotland Yard decided to let him make a little more money while they investigated the source of his supply. They put a close tail on Schwab and in due course were led to Victoria Station and thence to the Mexican courier. At that stage, since a foreign country was concerned, the Secret Service had had to be called in and Bond was ordered to find out where the courier got his supplies and to destroy the channel at source.

Bond did as he was told. He flew to Mexico City and quickly got to the Madre de Cacao. Thence, posing as a buyer for the London traffic, he got back to the big Mexican. The Mexican received him amiably and referred him to Blackwell. Bond had rather taken to Blackwell. He knew nothing about Blackwell’s sister, but the man was obviously an amateur and his bitterness about the heroin ban in England rang true. Bond broke into his warehouse one night and left a thermite bomb. He then went and sat in a café a mile away and watched the flames leap above the horizon of roof-tops and listened to the silver cascade of the fire-brigade bells. The next morning he telephoned Blackwell. He stretched a handkerchief across the mouthpiece and spoke through it.

‘Sorry you lost your business last night. I’m afraid your insurance won’t cover those stocks of soil you were researching.’

‘Who’s that? Who’s speaking?’

‘I’m from England. That stuff of yours has killed quite a lot of young people over there. Damaged a lot of others. Santos won’t be coming to England any more with his diplomatic bag. Schwab will be in jail by tonight. That fellow Bond you’ve been seeing, he won’t get out of the net either. The police are after him now.’

Frightened words came back down the line.

‘All right, but just don’t do it again. Stick to fertilisers.’

Bond hung up.

Blackwell wouldn’t have had the wits. It was obviously the big Mexican who had seen through the false trail. Bond had taken the precaution to move his hotel, but that night, as he walked home after a last drink at the Copacabana, a man suddenly stood in his way. The man wore a dirty white linen suit and a chauffeur’s white cap that was too big for his head. There were deep blue shadows under Aztec cheekbones. In one corner of the slash of a mouth there was a toothpick and in the other a cigarette. The eyes were bright pinpricks of marijuana.

‘You like woman? Make jigajig?’

‘No.’

‘Coloured girl? Fine jungle tail?’

‘No.’

‘Mebbe pictures?’

The gesture of the hand slipping into the coat was so well known to Bond, so full of old dangers, that, when the hand flashed out and the long silver finger went for his throat, Bond was on balance and ready for it.

Almost automatically, Bond went into the ‘Parry Defence against Underhand Thrust’ out of the book. His right arm cut across, his body swivelling with it. The two forearms met midway between the two bodies, banging the Mexican’s knife-arm off target and opening his guard for a crashing short-arm chin jab with Bond’s left. Bond’s stiff, locked wrist had not travelled far, perhaps two feet, but the heel of his palm, with fingers spread for rigidity, had come up and under the man’s chin with terrific force. The blow almost lifted the man off the sidewalk. Perhaps it had been that blow that had killed the Mexican, broken his neck, but as he staggered back on his way to the ground, Bond had drawn back his right hand and slashed sideways at the taut, offered throat. It was the deadly hand-edge blow to the Adam’s apple, delivered with the fingers locked into a blade, that had been the stand-by of the Commandos. If the Mexican was still alive, he was certainly dead before he hit the ground.

Bond stood for a moment, his chest heaving, and looked at the crumpled pile of cheap clothes flung down in the dust. He glanced up and down the street. There was no one. Some cars passed. Others had perhaps passed during the fight, but it had been in the shadows. Bond knelt down beside the body. There was no pulse. Already the eyes that had been so bright with marijuana were glazing. The house in which the Mexican had lived was empty. The tenant had left.

Bond picked up the body and laid it against a wall in deeper shadow. He brushed his hands down his clothes, felt to see if his tie was straight and went on to his hotel.

At dawn Bond had got up and shaved and driven to the airport where he took the first plane out of Mexico. It happened to be going to Caracas. Bond flew to Caracas and hung about in the transit lounge until there was a plane for Miami, a Transamerica Constellation that would take him on that same evening to New York.

Again the tannoy buzzed and echoed. ‘Transamerica regrets to announce a delay on their flight TR618 to New York due to a mechanical defect. The new departure time will be at 8 a.m. Will all passengers please report to the Transamerica ticket counter where arrangements for their overnight accommodation will be made. Thank you.’

So! That too! Should he transfer to another flight or spend the night in Miami? Bond had forgotten his drink. He picked it up and, tilting his head back, swallowed the bourbon to the last drop. The ice tinkled cheerfully against his teeth. That was it. That was an idea. He would spend the night in Miami and get drunk, stinking drunk so that he would have to be carried to bed by whatever tart he had picked up. He hadn’t been drunk for years. It was high time. This extra night, thrown at him out of the blue, was a spare night, a gone night. He would put it to good purpose. It was time he let himself go. He was too tense, too introspective. What the hell was he doing, glooming about this Mexican, this capungo who had been sent to kill him? It had been kill or get killed. Anyway, people were killing other people all the time, all over the world. People were using their motor cars to kill with. They were carrying infectious diseases around, blowing microbes in other people’s faces, leaving gas-jets turned on in kitchens, pumping out carbon monoxide in closed garages. How many people, for instance, were involved in manufacturing H-bombs, from the miners who mined the uranium to the shareholders who owned the mining shares? Was there any person in the world who wasn’t somehow, perhaps only statistically, involved in killing his neighbour?

The last light of the day had gone. Below the indigo sky the flare paths twinkled green and yellow and threw tiny reflections off the oily skin of the tarmac. With a shattering roar a DC7 hurtled down the main green lane. The windows in the transit lounge rattled softly. People got up to watch. Bond tried to read their expressions. Did they hope the plane would crash – give them something to watch, something to talk about, something to fill their empty lives? Or did they wish it well? Which way were they willing the sixty passengers? To live or to die?

Bond’s lips turned down. Cut it out. Stop being so damned morbid. All this is just reaction from a dirty assignment. You’re stale, tired of having to be tough. You want a change. You’ve seen too much death. You want a slice of life – easy, soft, high.

Bond was conscious of steps approaching. They stopped at his side. Bond looked up. It was a clean, rich-looking, middle-aged man. His expression was embarrassed, deprecating.

‘Pardon me, but surely it’s Mr Bond . . . Mr – er – James Bond?’

2

Living It Up

Bond liked anonymity. His ‘Yes, it is’ was discouraging.

‘Well, that’s a mighty rare coincidence.’ The man held out his hand. Bond rose slowly, took the hand and released it. The hand was pulpy and unarticulated – like a hand-shaped mud pack, or an inflated rubber glove. ‘My name is Du Pont. Junius Du Pont. I guess you won’t remember me, but we’ve met before. Mind if I sit down?’

The face, the name? Yes, there was something familiar. Long ago. Not in America. Bond searched the files while he summed the man up. Mr Du Pont was about fifty – pink, clean-shaven and dressed in the conventional disguise with which Brooks Brothers cover the shame of American millionaires. He wore a single-breasted dark tan tropical suit and a white silk shirt with a shallow collar. The rolled ends of the collar were joined by a gold safety pin beneath the knot of a narrow dark red and blue striped tie that fractionally wasn’t the Brigade of Guards’. The cuffs of the shirt protruded half an inch below the cuffs of the coat and showed cabochon crystal links containing miniature trout flies. The socks were charcoal-grey silk and the shoes were old and polished mahogany and hinted Peal. The man carried a dark, narrow-brimmed straw homburg with a wide claret ribbon.

Mr Du Pont sat down opposite Bond and produced cigarettes and a plain gold Zippo lighter. Bond noticed that he was sweating slightly. He decided that Mr Du Pont was what he appeared to be, a very rich American, mildly embarrassed. He knew he had seen him before, but he had no idea where or when.

‘Smoke?’

‘Thank you.’ It was a Parliament. Bond affected not to notice the offered lighter. He disliked held-out lighters. He picked up his own and lit the cigarette.

‘France, ’51, Royale-les-Eaux.’ Mr Du Pont looked eagerly at Bond. ‘That Casino. Ethel, that’s Mrs Du Pont, and me were next to you at the table the night you had the big game with the Frenchman.’

Bond’s memory raced back. Yes, of course. The Du Ponts had been Nos 4 and 5 at the baccarat table. Bond had been 6. They had seemed harmless people. He had been glad to have such a solid bulwark on his left on that fantastic night when he had broken Le Chiffre. Now Bond saw it all again – the bright pool of light on the green baize, the pink crab hands across the table scuttling out for the cards. He smelt the smoke and the harsh tang of his own sweat. That had been a night! Bond looked across at Mr Du Pont and smiled at the memory. ‘Yes, of course I remember. Sorry I was slow. But that was quite a night. I wasn’t thinking of much except my cards.’

Mr Du Pont grinned back, happy and relieved. ‘Why, gosh, Mr Bond. Of course I understand. And I do hope you’ll pardon me for butting in. You see—’ He snapped his fingers for a waitress. ‘But we must have a drink to celebrate. What’ll you have?’

‘Thanks. Bourbon on the rocks.’

‘And dimple Haig and water.’ The waitress went away.

Mr Du Pont leant forward, beaming. A whiff of soap or aftershave lotion came across the table. Lentheric? ‘I knew it was you. As soon as I saw you sitting there. But I thought to myself, Junius, you don’t often make an error over a face, but let’s just go make sure. Well, I was flying Transamerican tonight and, when they announced the delay, I watched your expression and, if you’ll pardon me, Mr Bond, it was pretty clear from the look on your face that you had been flying Transamerican too.’ He waited for Bond to nod. He hurried on. ‘So I ran down to the ticket counter and had me a look at the passenger list. Sure enough, there it was, “J. Bond”.’

Mr Du Pont sat back, pleased with his cleverness. The drinks came. He raised his glass. ‘Your very good health, sir. This sure is my lucky day.’

Bond smiled non-committally and drank.

Mr Du Pont leant forward again. He looked round. There was nobody at the nearby tables. Nevertheless he lowered his voice. ‘I guess you’ll be saying to yourself, well, it’s nice to see Junius Du Pont again, but what’s the score? Why’s he so particularly happy at seeing me on just this night?’ Mr Du Pont raised his eyebrows as if acting Bond’s part for him. Bond put on a face of polite inquiry. Mr Du Pont leant still further across the table. ‘Now, I hope you’ll forgive me, Mr Bond. It’s not like me to pry into other people’s secre—er – affairs. But, after that game at Royale, I did hear that you were not only a grand card-player, but also that you were – er – how shall I put it? – that you were a sort of – er – investigator. You know, kind of intelligence operative.’ Mr Du Pont’s indiscretion had made him go very red in the face. He sat back and took out a handkerchief and wiped his forehead. He looked anxiously at Bond.

Bond shrugged his shoulders. The grey-blue eyes that looked into Mr Du Pont’s eyes, which had turned hard and watchful despite his embarrassment, held a mixture of candour, irony and self-deprecation. ‘I used to dabble in that kind of thing. Hangover from the war. One still thought it was fun playing Red Indians. But there’s no future in it in peacetime.’

‘Quite, quite.’ Mr Du Pont made a throwaway gesture with the hand that held the cigarette. His eyes evaded Bond’s as he put the next question, waited for the next lie. (Bond thought, there’s a wolf in this Brooks Brothers clothing. This is a shrewd man.) ‘And now you’ve settled down?’ Mr Du Pont smiled paternally. ‘What did you choose, if you’ll pardon the question?’

‘Import and Export. I’m with Universal. Perhaps you’ve come across them.’

Mr Du Pont continued to play the game. ‘Hm. Universal. Let me see. Why, yes, sure I’ve heard of them. Can’t say I’ve ever done business with them, but I guess it’s never too late.’ He chuckled fatly. ‘I’ve got quite a heap of interests all over the place. Only stuff I can honestly say I’m not interested in is chemicals. Maybe it’s my misfortune, Mr Bond, but I’m not one of the chemical Du Ponts.’

Bond decided that the man was quite satisfied with the particular brand of Du Pont he happened to be. He made no comment. He glanced at his watch to hurry Mr Du Pont’s play of the hand. He made a note to handle his own cards carefully. Mr Du Pont had a nice pink kindly baby-face with a puckered, rather feminine turndown mouth. He looked as harmless as any of the middle-aged Americans with cameras who stand outside Buckingham Palace. But Bond sensed many tough, sharp qualities behind the fuddyduddy façade.

Mr Du Pont’s sensitive eye caught Bond’s glance at his watch. He consulted his own. ‘My, oh my! Seven o’clock and here I’ve been talking away without coming to the point. Now, see here, Mr Bond. I’ve got me a problem on which I’d greatly appreciate your guidance. If you can spare me the time and if you were counting on stopping over in Miami tonight I’d reckon it a real favour if you’d allow me to be your host.’ Mr Du Pont held up his hand. ‘Now, I think I can promise to make you comfortable. So happens I own a piece of the Floridiana. Maybe you heard we opened around Christmas time? Doing a great business I’m happy to say. Really pushing that little old Fountain Blue,’ Mr Du Pont laughed indulgently. ‘That’s what we call the Fontainebleau down here. Now, what do you say, Mr Bond? You shall have the best suite – even if it means putting some good paying customers out on the sidewalk. And you’d be doing me a real favour.’ Mr Du Pont looked imploring.

Bond had already decided to accept – blind. Whatever Mr Du Pont’s problem – blackmail, gangsters, women – it would be some typical form of rich man’s worry. Here was a slice of the easy life he had been asking for. Take it. Bond started to say something politely deprecating. Mr Du Pont interrupted. ‘Please, please, Mr Bond. And believe me, I’m grateful, very grateful indeed.’ He snapped his fingers for the waitress. When she came, he turned away from Bond and settled the bill out of Bond’s sight. Like many very rich men he considered that showing his money, letting someone see how much he tipped, amounted to indecent exposure. He thrust his roll back into his trouser pocket (the hip pocket is not the place among the rich) and took Bond by the arm. He sensed Bond’s resistance to the contact and removed his hand. They went down the stairs to the main hall.

‘Now, let’s just straighten out your reservation.’ Mr Du Pont headed for the Transamerica ticket counter. In a few curt phrases Mr Du Pont showed his power and efficiency in his own, his American, realm.

‘Yes, Mr Du Pont. Surely, Mr Du Pont. I’ll take care of that, Mr Du Pont.’

Outside, a gleaming Chrysler Imperial sighed up to the kerb. A tough-looking chauffeur in a biscuit-coloured uniform hurried to open the door. Bond stepped in and settled down in the soft upholstery. The interior of the car was deliciously cool, almost cold. The Transamerican representative bustled out with Bond’s suitcase, handed it to the chauffeur and, with a half-bow, went back into the terminal. ‘Bill’s on the Beach,’ said Mr Du Pont to the chauffeur and the big car slid away through the crowded parking lots and out on to the parkway.

Mr Du Pont settled back. ‘Hope you like stone crabs, Mr Bond. Ever tried them?’

Bond said he had, that he liked them very much.

Mr Du Pont talked about Bill’s on the Beach and about the relative merits of stone and Alaska crabmeat while the Chrysler Imperial sped through downtown Miami, along Biscayne Boulevard and across Biscayne Bay by the Douglas MacArthur Causeway. Bond made appropriate comments, letting himself be carried along on the gracious stream of speed and comfort and rich small-talk.

They drew up at a white-painted, mock-Regency frontage in clapboard and stucco. A scrawl of pink neon said: BILL’S ON THE BEACH. While Bond got out, Mr Du Pont gave his instructions to the chauffeur. Bond heard the words: ‘The Aloha Suite,’ and ‘If there’s any trouble, tell Mr Fairlie to call me here. Right?’

They went up the steps. Inside, the big room was decorated in white with pink muslin swags over the windows. There were pink lights on the tables. The restaurant was crowded with sunburnt people in expensive tropical get-ups – brilliant garish shirts, jangling gold bangles, dark glasses with jewelled rims, cute native straw hats. There was a confusion of scents. The wry smell of bodies that had been all day in the sun came through.

Bill, a pansified Italian, hurried towards them. ‘Why, Mr Du Pont. Is a pleasure, sir. Little crowded tonight. Soon fix you up. Please this way please.’ Holding a large leather-bound menu above his head the man weaved his way between the diners to the best table in the room, a corner table for six. He pulled out two chairs, snapped his fingers for the maître d’hôtel and the wine waiter, spread two menus in front of them, exchanged compliments with Mr Du Pont and left them.

Mr Du Pont slapped his menu shut. He said to Bond, ‘Now, why don’t you just leave this to me? If there’s anything you don’t like, send it back.’ And to the head waiter, ‘Stone crabs. Not frozen. Fresh. Melted butter. Thick toast. Right?’

‘Very good, Mr Du Pont.’ The wine-waiter, washing his hands, took the waiter’s place.

‘Two pints of pink champagne. The Pommery ’50. Silver tankards. Right?’

‘Vairry good, Mr Du Pont. A cocktail to start?’

Mr Du Pont turned to Bond. He smiled and raised his eyebrows.

Bond said, ‘Vodka martini, please. With a slice of lemon peel.’

‘Make it two,’ said Mr Du Pont. ‘Doubles.’ The wine-waiter hurried off. Mr Du Pont sat back and produced his cigarettes and lighter. He looked round the room, answered one or two waves with a smile and a lift of the hand and glanced at the neighbouring tables. He edged his chair nearer to Bond’s. ‘Can’t help the noise, I’m afraid,’ he said apologetically. ‘Only come here for the crabs. They’re out of this world. Hope you’re not allergic to them. Once brought a girl here and fed her crabs and her lips swelled up like cycle tyres.’

Bond was amused at the change in Mr Du Pont – this racy talk, the authority of manner once Mr Du Pont thought he had got Bond on the hook, on his payroll. He was a different man from the shy embarrassed suitor who had solicited Bond at the airport. What did Mr Du Pont want from Bond? It would be coming any minute now, the proposition. Bond said, ‘I haven’t got any allergies.’

‘Good, good.’

There was a pause. Mr Du Pont snapped the lid of his lighter up and down several times. He realised he was making an irritating noise and pushed it away from him. He made up his mind. He said, speaking at his hands on the table in front of him, ‘You ever play canasta, Mr Bond?’

‘Yes, it’s a good game. I like it.’

‘Two-handed canasta?’

‘I have done. It’s not so much fun. If you don’t make a fool of yourself – if neither of you do – it tends to even out. Law of averages in the cards. No chance of making much difference in the play.’

Mr Du Pont nodded emphatically. ‘Just so. That’s what I’ve said to myself. Over a hundred games or so, two equal players will end up equal. Not such a good game as gin or Oklahoma, but in a way that’s just what I like about it. You pass the time, you handle plenty of cards, you have your ups and downs, no one gets hurt. Right?’

Bond nodded. The martinis came. Mr Du Pont said to the wine-waiter, ‘Bring two more in ten minutes.’ They drank. Mr Du Pont turned and faced Bond. His face was petulant, crumpled. He said, ‘What would you say, Mr Bond, if I told you I’d lost twenty-five thousand dollars in a week playing two-handed canasta?’ Bond was about to reply. Mr Du Pont held up his hand. ‘And mark you, I’m a good card-player. Member of the Regency Club. Play a lot with people like Charlie Goren, Johnny Crawford – at bridge that is. But what I mean, I know my way around at the card-table.’ Mr Du Pont probed Bond’s eyes.

‘If you’ve been playing with the same man all the time, you’ve been cheated.’

‘Ex-actly.’ Mr Du Pont slapped the tablecloth. He sat back. ‘Ex-actly. That’s what I said to myself after I’d lost – lost for four whole days. So I said to myself, this bastard is cheating me and by golly I’ll find out how he does it and have him hounded out of Miami. So I doubled the stakes and then doubled them again. He was quite happy about it. And I watched every card he played, every movement. Nothing! Not a hint or a sign. Cards not marked. New pack whenever I wanted one. My own cards. Never looked at my hand – couldn’t, as I always sat dead opposite him. No kibitzer to tip him off. And he just went on winning and winning. Won again this morning. And again this afternoon. Finally I got so mad at the game – I didn’t show it, mind you’ – Bond might think he had not been a sport – ‘I paid up politely. But, without telling this guy, I just packed my bag and got me to the airport and booked on the first plane to New York. Think of that!’ Mr Du Pont threw up his hands. ‘Running away. But twenty-five grand is twenty-five grand. I could see it getting to fifty, a hundred. And I just couldn’t stand another of these damned games and I couldn’t stand not being able to catch this guy out. So I took off. What do you think of that? Me, Junius Du Pont, throwing in the towel because I couldn’t take the licking any more!’

Bond grunted sympathetically. The second round of drinks came. Bond was mildly interested, he was always interested in anything to do with cards. He could see the scene, the two men playing and playing and the one man quietly shuffling and dealing away and marking up his score while the other was always throwing his cards into the middle of the table with a gesture of controlled disgust. Mr Du Pont was obviously being cheated. How? Bond said, ‘Twenty-five thousand’s a lot of money. What stakes were you playing?’

Mr Du Pont looked sheepish. ‘Quarter a point, then fifty cents, then a dollar. Pretty high I guess with the games averaging around two thousand points. Even at a quarter, that makes five hundred dollars a game. At a dollar a point, if you go on losing, it’s murder.’

‘You must have won sometimes.’

‘Oh sure, but somehow, just as I’d got the s.o.b. all set for a killing, he’d put down as many of his cards as he could meld. Got out of the bag. Sure, I won some small change, but only when he needed a hundred and twenty to go down and I’d got all the wild cards. But you know how it is with canasta, you have to discard right. You lay traps to make the other guy hand you the pack. Well, darn it, he seemed to be psychic! Whenever I laid a trap, he’d dodge it, and almost every time he laid one for me I’d fall into it. As for giving me the pack – why, he’d choose the damnedest cards when he was pushed – discard singletons, aces, God knows what, and always get away with it. It was just as if he knew every card in my hand.’

‘Any mirrors in the room?’

‘Heck, no! We always played outdoors. He said he wanted to get himself a sunburn. Certainly did that. Red as lobster. He’d only play in the mornings and afternoons. Said if he played in the evening he couldn’t get to sleep.’

‘Who is this man, anyway? What’s his name?’

‘Goldfinger.’

‘First name?’

‘Auric. That means golden, doesn’t it? He certainly is that. Got flaming red hair.’

‘Nationality?’

‘You won’t believe it, but he’s a Britisher. Domiciled in Nassau. You’d think he’d be a Jew from the name, but he doesn’t look it. We’re restricted at the Floridiana. Wouldn’t have got in if he had been. Nassavian passport. Age forty-two. Unmarried. Profession, broker. Got all this from his passport. Had me a peek via the house detective when I started to play with him.’

‘What sort of broker?’

Du Pont smiled grimly. ‘I asked him. He said, “Oh, anything that comes along.” Evasive sort of fellow. Clams up if you ask him a direct question. Talks away quite pleasantly about nothing at all.’

‘What’s he worth?’

‘Ha!’ said Mr Du Pont explosively. ‘That’s the damnedest thing. He’s loaded. But loaded! I got my bank to check with Nassau. He’s lousy with it. Millionaires are a dime a dozen in Nassau, but he’s rated either first or second among them. Seems he keeps his money in gold bars. Shifts them around the world a lot to get the benefit of changes in the gold price. Acts like a damn federal bank. Doesn’t trust currencies. Can’t say he’s wrong in that, and seeing how he’s one of the richest men in the world there must be something to his system. But the point is, if he’s as rich as that, what the hell does he want to take a lousy twenty-five grand off me for?’

A bustle of waiters round their table saved Bond having to think up a reply. With ceremony, a wide silver dish of crabs, big ones, their shells and claws broken, was placed in the middle of the table. A silver sauceboat brimming with melted butter and a long rack of toast was put beside each of their plates. The tankards of champagne frothed pink. Finally, with an oily smirk, the head waiter came behind their chairs and, in turn, tied round their necks long white silken bibs that reached down to the lap.

Bond was reminded of Charles Laughton playing Henry VIII, but neither Mr Du Pont nor the neighbouring diners seemed surprised at the hoggish display. Mr Du Pont, with a gleeful ‘Every man for himself’, raked several hunks of crab on to his plate, doused them liberally in melted butter and dug in. Bond followed suit and proceeded to eat, or rather devour, the most delicious meal he had had in his life.

The meat of the stone crabs was the tenderest, sweetest shellfish he had ever tasted. It was perfectly set off by the dry toast and slightly burnt taste of the melted butter. The champagne seemed to have the faintest scent of strawberries. It was ice-cold. After each helping of crab, the champagne cleaned the palate for the next. They ate steadily and with absorption and hardly exchanged a word until the dish was cleared.

With a slight belch, Mr Du Pont for the last time wiped butter off his chin with his silken bib and sat back. His face was flushed. He looked proudly at Bond. He said reverently, ‘Mr Bond, I doubt if anywhere in the world a man has eaten as good a dinner as that tonight. What do you say?’

Bond thought, I asked for the easy life, the rich life. How do I like it? How do I like eating like a pig and hearing remarks like that? Suddenly the idea of ever having another meal like this, or indeed any other meal with Mr Du Pont, revolted him. He felt momentarily ashamed of his disgust. He had asked and it had been given. It was the puritan in him that couldn’t take it. He had made his wish and the wish had not only been granted, it had been stuffed down his throat. Bond said, ‘I don’t know about that, but it was certainly very good.’

Mr Du Pont was satisfied. He called for coffee. Bond refused the offer of cigars or liqueurs. He lit a cigarette and waited with interest for the catch to be presented. He knew there would be one. It was obvious that all this was part of the come-on. Well, let it come.

Mr Du Pont cleared his throat. ‘And now, Mr Bond, I have a proposition to put to you.’ He stared at Bond, trying to gauge his reaction in advance.

‘Yes?’

‘It surely was providential to meet you like that at the airport.’ Mr Du Pont’s voice was grave, sincere. ‘I’ve never forgotten our first meeting at Royale. I recall every detail of it – your coolness, your daring, your handling of the cards.’ Bond looked down at the tablecloth. But Mr Du Pont had got tired of his peroration. He said hurriedly, ‘Mr Bond, I will pay you ten thousand dollars to stay here as my guest until you have discovered how this man Goldfinger beats me at cards.’

Bond looked Mr Du Pont in the eye. He said, ‘That’s a handsome offer, Mr Du Pont. But I have to get back to London. I must be in New York to catch my plane within forty-eight hours. If you will play your usual sessions tomorrow morning and afternoon I should have plenty of time to find out the answer. But I must leave tomorrow night, whether I can help you or not. Done?’

‘Done,’ said Mr Du Pont.

3

The Man with Agoraphobia

The flapping of the curtains wakened Bond. He threw off the single sheet and walked across the thick pile carpet to the picture window that filled the whole of one wall. He drew back the curtains and went out on to the sun-filled balcony.

The black and white chequerboard tiles were warm, almost hot to the feet although it could not yet be eight o’clock. A brisk inshore breeze was blowing off the sea, straining the flags of all nations that flew along the pier of the private yacht basin. The breeze was humid and smelt strongly of the sea. Bond guessed it was the breeze that the visitors like, but the residents hate. It would rust the metal fittings in their homes, fox the pages of their books, rot their wallpaper and pictures, breed damp-rot in their clothes.

Twelve storeys down the formal gardens, dotted with palm trees and beds of bright croton and traced with neat gravel walks between avenues of bougainvillaea, were rich and dull. Gardeners were working, raking the paths and picking up leaves with the lethargic slow motion of coloured help. Two mowers were at work on the lawns and, where they had already been, sprinklers were gracefully flinging handfuls of spray.

Directly below Bond, the elegant curve of the Cabana Club swept down to the beach – two storeys of changing-rooms below a flat roof dotted with chairs and tables and an occasional red and white striped umbrella. Within the curve was the brilliant green oblong of the Olympic-length swimming pool fringed on all sides by row upon row of mattressed steamer chairs on which the customers would soon be getting their fifty-dollar-a-day sunburn. White-jacketed men were working among them, straightening the lines of chairs, turning the mattresses and sweeping up yesterday’s cigarette butts. Beyond was the long, golden beach and the sea, and more men – raking the tideline, putting up the umbrellas, laying out mattresses. No wonder the neat card inside Bond’s wardrobe had said that the cost of the Aloha Suite was two hundred dollars a day. Bond made a rough calculation. If he was paying the bill, it would take him just three weeks to spend his whole salary for the year. Bond smiled cheerfully to himself. He went back into the bedroom, picked up the telephone and ordered himself a delicious, wasteful breakfast, a carton of king-size Chesterfields and the newspapers.

By the time he had shaved and had an ice-cold shower and dressed it was eight o’clock. He walked through into the elegant sitting-room and found a waiter in a uniform of plum and gold laying out his breakfast beside the window. Bond glanced at the Miami Herald. The front page was devoted to yesterday’s failure of an American ICBM at the nearby Cape Canaveral and a bad upset in a big race at Hialeah.

Bond dropped the paper on the floor and sat down and slowly ate his breakfast and thought about Mr Du Pont and Mr Goldfinger.

His thoughts were inconclusive. Mr Du Pont was either a much worse player than he thought, which seemed unlikely on Bond’s reading of his tough, shrewd character, or else Goldfinger was a cheat. If Goldfinger cheated at cards, although he didn’t need the money, it was certain that he had also made himself rich by cheating or sharp practice on a much bigger scale. Bond was interested in big crooks. He looked forward to his first sight of Goldfinger. He also looked forward to penetrating Goldfinger’s highly successful and, on the face of it, highly mysterious method of fleecing Mr Du Pont. It was going to be a most entertaining day. Idly Bond waited for it to get under way.

The plan was that he would meet Mr Du Pont in the garden at ten o’clock. The story would be that Bond had flown down from New York to try and sell Mr Du Pont a block of shares from an English holding in a Canadian Natural Gas property. The matter was clearly confidential and Goldfinger would not think of questioning Bond about details. Shares, Natural Gas, Canada. That was all Bond needed to remember. They would go along together to the roof of the Cabana Club where the game was played and Bond would read his paper and watch. After luncheon, during which Bond and Mr Du Pont would discuss their ‘business’, there would be the same routine. Mr Du Pont had inquired if there was anything else he could arrange. Bond had asked for the number of Mr Goldfinger’s suite and a pass-key. He had explained that if Goldfinger was any kind of a professional card-sharp, or even an expert amateur, he would travel with the usual tools of the trade – marked and shaved cards, the apparatus for the Short Arm Delivery, and so forth. Mr Du Pont had said he would give Bond the key when they met in the garden. He would have no difficulty getting one from the manager.

After breakfast, Bond relaxed and gazed into the middle distance of the sea. He was not keyed up by the job on hand, only interested and amused. It was just the kind of job he had needed to clear his palate after Mexico.

At half past nine Bond left his suite and wandered along the corridors of his floor, getting lost on his way to the elevator in order to reconnoitre the layout of the hotel. Then, having met the same maid twice, he asked his way and went down in the elevator and moved among the scattering of early risers through the Pineapple Shopping Arcade. He glanced into the Bamboo Coffee Shoppe, the Rendezvous Bar, the La Tropicala dining-room, the Kittekat Klub for children and the Boom-Boom Nighterie. He then went purposefully out into the garden. Mr Du Pont, now dressed ‘for the beach’ by Abercrombie & Fitch, gave him the pass-key to Goldfinger’s suite. They sauntered over to the Cabana Club and climbed the two short flights of stairs to the top deck.

Bond’s first view of Mr Goldfinger was startling. At the far corner of the roof, just below the cliff of the hotel, a man was lying back with his legs up on a steamer chair. He was wearing nothing but a yellow satin bikini slip, dark glasses and a pair of wide tin wings under his chin. The wings, which appeared to fit round his neck, stretched out across his shoulders and beyond them and then curved up slightly to rounded tips.

Bond said, ‘What the hell’s he wearing round his neck?’

‘You never seen one of those?’ Mr Du Pont was surprised. ‘That’s a gadget to help your tan. Polished tin. Reflects the sun up under your chin and behind the ears – the bits that wouldn’t normally catch the sun.’

‘Well, well,’ said Bond.

When they were a few yards from the reclining figure Mr Du Pont called out cheerfully, in what seemed to Bond an overloud voice, ‘Hi there!’

Mr Goldfinger did not stir.

Mr Du Pont said in his normal voice, ‘He’s very deaf.’ They were now at Mr Goldfinger’s feet. Mr Du Pont repeated his hail.

Mr Goldfinger sat up sharply. He removed his dark glasses. ‘Why, hullo there.’ He unhitched the wings from round his neck, put them carefully on the ground beside him and got heavily to his feet. He looked at Bond with slow, inquiring eyes.

‘Like you to meet Mr Bond, James Bond. Friend of mine from New York. Countryman of yours. Come down to try and talk me into a bit of business.’

Mr Goldfinger held out a hand. ‘Pleased to meet you, Mr Bomb.’

Bond took the hand. It was hard and dry. There was the briefest pressure and it was withdrawn. For an instant Mr Goldfinger’s pale, china-blue eyes opened wide and stared hard at Bond. They stared right through his face to the back of his skull. Then the lids drooped, the shutter closed over the X-ray, and Mr Goldfinger took the exposed plate and slipped it away in his filing system.

‘So no game today.’ The voice was flat, colourless. The words were more of a statement than a question.

‘Whaddya mean, no game?’ shouted Mr Du Pont boisterously. ‘You weren’t thinking I’d let you hang on to my money? Got to get it back or I shan’t be able to leave this darned hotel,’ Mr Du Pont chuckled richly. ‘I’ll tell Sam to fix the table. James here says he doesn’t know much about cards and he’d like to learn the game. That right, James?’ He turned to Bond. ‘Sure you’ll be all right with your paper and the sunshine?’

‘I’d be glad of the rest,’ said Bond. ‘Been travelling too much.’

Again the eyes bored into Bond and then drooped. ‘I’ll get some clothes on. I had intended to have a golf lesson this afternoon from Mr Armour at the Boca Raton. But cards have priority among my hobbies. My tendency to uncock the wrists too early with the midirons will have to wait.’ The eyes rested incuriously on Bond. ‘You play golf, Mr Bomb?’

Bond raised his voice. ‘Occasionally, when I’m in England.’

‘And where do you play?’

‘Huntercombe.’

‘Ah – a pleasant little course. I have recently joined the Royal St Marks. Sandwich is close to one of my business interests. You know it?’

‘I have played there.’

‘What is your handicap?’

‘Nine.’

‘That is a coincidence. So is mine. We must have a game one day.’ Mr Goldfinger bent down and picked up his tin wings. He said to Mr Du Pont, ‘I will be with you in five minutes.’ He walked slowly off towards the stairs.

Bond was amused. This social sniffing at him had been done with just the right casual touch of the tycoon who didn’t really care if Bond was alive or dead but, since he was there and alive, might as well place him in an approximate category.

Mr Du Pont gave instructions to a steward in a white coat. Two others were already setting up a card-table. Bond walked to the rail that surrounded the roof and looked down into the garden, reflecting on Mr Goldfinger.

He was impressed. Mr Goldfinger was one of the most relaxed men Bond had ever met. It showed in the economy of his movement, of his speech, of his expressions. Mr Goldfinger wasted no effort, yet there was something coiled, compressed, in the immobility of the man.

When Goldfinger had stood up, the first thing that had struck Bond was that everything was out of proportion. Goldfinger was short, not more than five feet tall, and on top of the thick body and blunt, peasant legs, was set, almost directly into the shoulders, a huge and it seemed exactly round head. It was as if Goldfinger had been put together with bits of other people’s bodies. Nothing seemed to belong. Perhaps, Bond thought, it was to conceal his ugliness that Goldfinger made such a fetish of sunburn. Without the red-brown camouflage the pale body would be grotesque. The face, under the cliff of crew-cut carroty hair, was as startling, without being as ugly, as the body. It was moon-shaped without being moon-like. The forehead was fine and high and the thin sandy brows were level above the large light blue eyes fringed with pale lashes. The nose was fleshily aquiline between high cheekbones and cheeks that were more muscular than fat. The mouth was thin and dead straight, but beautifully drawn. The chin and jaws were firm and glinted with health. To sum up, thought Bond, it was the face of a thinker, perhaps a scientist, who was ruthless, sensual, stoical and tough. An odd combination.