Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

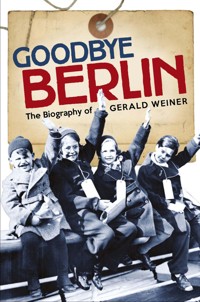

The 24th of March, 1939, was a poignant day for twelve-year-old Gerald Wiener. He was on a train pulling out of Berlin and he was on his way to the UK to escape persecution in Nazi Germany. He was one of the thousands of unaccompanied children saved by the Kindertransport. Looked after by two sisters in Oxford, his abilities as a scholar became apparent and from an early age he was set on the road to academic achievement. There followed a distinguished career as a research scientist in Edinburgh, where he made a genetic discovery that received international recognition. His research department was a centre of excellence and members of his team went on to make an astonishing breakthrough in genetics, the cloning of Dolly the sheep. During his career Gerald was also in demand to assist agricultural development in China, India, the secretive North Korea and many other countries, and his trips during these years are full of incident and fascinating human and social insights. It was while he was on a postdoctoral fellowship in the USA that he discovered he had a large family in California. He had known nothing of them as his mother and father had parted when he was only two years old. His aunt and stepmother gave him compelling accounts of their escapes from Hitler, via Shanghai, and life under the Japanese during the War. Their stories, and that of Gerald himself, are amazing tales of resilience and triumph over adversity. This book shows how one man's life and achievements mirror the great events of the second half of the twentieth century and the opening years of the new millennium.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GOODBYE BERLIN

First published in 2016 byBirlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Margaret M. Dunlop 2016

Foreword copyright © Grahame Bulfield 2016

The moral right of Margaret M. Dunlop to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78027 420 1eISBN 978 0 85790 348 8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Author’s Preface

1Hello, Dolly

2Berlin Childhood

3Early Schooldays

4Goodbye, Berlin

5New Beginnings

6The Spooners of Oxford

7Farming

8Student Days

9Meeting His First Wife

10The Scientist and the Big Sheep Experiment

11To the USA

12Finding a New Family

13The Lucky Break

14Ethiopia

15Melbourne Conference and a Return to Ethiopia

16A Homecoming

17Edinburgh Years and A Fateful Meeting

18Wedding Bells

19Return to the USA

20The American Family’s Story

21Revelations in Golden Gate Park

22Luise’s Story

23A Journey to Meet a Brother

24A Sentimental Destination

25Marion’s Story

26Catching Up With Old Friends

27From Glory Through Turmoil to Dolly

28Retirement, a New Career, and a Quick Exit from Yemen

291988 – A Busy Year

30The Road to the Yak Country and Bangladesh

31Return Visits to China

32A North Korean Interlude

33Return to Berlin

34Back to India

35Yak Conferences and New Visits

36Events, Serious and Entertaining, in China

37Later Years

Index

List of Illustrations

Degree and non-degree Agriculture students with Joe Gordon, acting director of studies, at George Square, Edinburgh, 1947

Reunion party with Prof. Peter Wilson at King’s Buildings, 1997

Dolly the sheep

Gerald’s grandfather Hermann

Gerald’s mother, Luise

Aunt Erna with Marion

Cousin Marion and Gerald, aged five

Uncle Erich

Gerald, aged three

Thea, Paul (Gerald’s father), Luise, Paul’s parents and in-laws, 1925

Gerald, aged twelve

St Mary’s (University) Church, Oxford

Gerald’s first graduation (BSc, Edinburgh), 1947

Rosemary and Ruth Spooner

Gerald with best friend Hardy Seidel, 1980

The three brothers: Gerald, Pete and Jerry

Some of the American family

Luise, aged eighteen

Luise as Assistant Matron in Dunfermline, Christmas 1940

Wedding Bells: Jimmy Harris (best man) Gerald, Margaret, Muriel Rodger (matron of honour), the Rev. McNeave

Marion in US forces, 1946

Marion with Gerald in Baltimore, 1992

Marion with GI mates in Germany, 1947

Gerald with Prof. and Mrs Ralph Goodell, 1992

Bon and Jai Nimbkar, India, 2000

Chanda Nimbkar with Gavan Bromilow, India, 2000

Gerald with itinerant sheep herders and their children, India, 1988

Gerald with Mel George and the yak project team at SW University for Nationalities, Chengdu, China, 1988

Gerald on back of a pack yak

Chinese Ministry of Agriculture delegation to the UK on visit to Gerald and Margaret in Biggar, 2007

Foreword

I have known Gerald Wiener as a geneticist for around fifty years. His research on the genetics of copper absorption and its role in swayback disease in sheep was groundbreaking, opening up a new area of physiological genetics of farm animals. In the research group he assembled around himself in Edinburgh were several young scientists who later became internationally famous researchers themselves, including Sir Ian Wilmut, leader of the team that cloned Dolly the sheep.

What I had not realised was the dramatic back-story to Gerald’s life – escaping from Hitler’s Germany on one of the last Kindertransports; being almost alone at twelve in England; looked after by a variety of people, some of whom showed him exceptional kindness; his discovery of a life-long interest in farm animals; and his determination to get to university. This he did, graduating from Edinburgh in 1947, and he remained there, latterly at the Roslin Institute, for the rest of his career. Later in life Gerald managed to find many members of the family he had left behind in Germany, including two brothers, in the USA, bringing a partially happy resolution to a dreadful twentieth- century story.

When Gerald retired as an active scientist he became a consultant for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), advising on cattle and sheep breeding in some challenging areas of the world, including Yemen, Ethiopia and North Korea. He also had long-term involvement in animal breeding programmes in India and China, where for many years he advised on yak breeding, especially in Tibet and South-west China. Gerald is the author of two books, one on tropical animal breeding and the other on yaks, the latter making him a recognised world expert on yak breeding.

For a research scientist, Gerald has had a difficult, challenging and finally rewarding life. This biography of a remarkable journey has been written in a flowing and intriguing narrative by the author Margaret M. Dunlop, who has accompanied Gerald on the latter part of it. It is a story of triumph over terrible adversity to international success.

Professor Grahame Bulfield, CBE, DSc, FRSE:Formerly Director and Chief Executive of Roslin Institute and Vice-Principal and Head of Science and Engineering at the University of Edinburgh

Author’s Preface

This book is the biography of a remarkable life of perseverance and success that began under the most inauspicious of circumstances in Nazi Germany. It is the story of Professor Gerald Wiener BSc, PhD, DSc, FRSE, CIBiol, FRSB, a scientist of some note but also a man of many other interests including, for most of his life, his involvement in community and church affairs.

The material for this biography derives from the recollections of the man himself, obtained through extensive discussion, and also recollections from members of his family, including, importantly, his mother, prior to her death. In addition, colleagues and friends of Gerald Wiener contributed and I am grateful to them all. Most of the information came from these discussions but there were also written and voice-recorded notes and reports from Gerald, and letters from him and from members of his family.

As Gerald Wiener’s wife in his later years I have had privileged access to all of this and was also able to add my own recollections. I persuaded him that his story had to be told, as it is both unusual and uplifting. After his initial reluctance to be thrown into the public eye in this way he gave his support and encouragement to this venture. Throughout the book I have refrained from writing in the first person about myself, so the ‘Margaret’ who appears in the opening chapter and in the latter half of the book is portrayed essentially as a bystander, as she would have been had the biography been written by another. I have used my pen name rather than my married name as I have two other books to my credit.

By way of acknowledgement I also wish to thank my two editors for helpful comments and suggestions. Any errors, however, are mine alone. I also want to mention that the staff of my publishers could not have been more helpful, most especially Andrew Simmons, editorial manager, for his patience and unfailing courtesy.

Margaret M. Dunlop

CHAPTER 1

Hello, Dolly

The sun was shining that day. It shone down on the castle, the great fortress of Edinburgh, perched high above the town. It warmed the milling crowds on Princes Street, the tourists and happy shoppers. It was a Friday in July 1997 and the mood of the city was light. In a café opposite the McEwan Hall of the University of Edinburgh the sun shone down upon a table where, blinking in the light, a clutch of distinguished-looking older citizens, grizzled and serious, were seated. They were part of a group who had graduated from that same university fifty years before, to the day.

The great city of Edinburgh is famed for its history in the world of education, and of modern ideas in politics and economics. It was referred to as a ‘hotbed of genius’ by the novelist Tobias Smollett. That was in the eighteenth century and some would say it hasn’t changed. The famous people of Edinburgh’s past make up an amazing list, including naturalist Charles Darwin, philosopher David Hume, surgeon Joseph Lister, inventor Alexander Graham Bell, writers Arthur Conan Doyle, R. L. Stevenson, J. M. Barrie and Sir Walter Scott.

On this day, from the doors of the McEwan Hall was streaming a bevy of young men and women, black-robed and smiling as they clutched their degree certificates. They stood in the sunlight, chattering with happiness under the gaze of friends and doting parents.

The contented older group sipped their coffee, their attention slowly turning to the scene on the other side of the road. Through the passing cars and pedestrians they could just catch glimpses of the joyful scenes taking place. They looked at each other and smiled. They had gathered that day in Edinburgh to celebrate. It was a reunion organised by Dr Gerald Wiener along with friends Ken Runcie and Barbara Findlay from the class of ’47. These seemingly ancient graduates, all former students of agriculture, were revisiting their former haunts in the city. One of the seated men called out to a group of young graduates, ‘Hey, we’re celebrating our graduation ceremony of fifty years ago!’ The students slowed, smiling in disbelief. The old man continued, ‘I’m from Iceland, you know, and this guy here came all the way from Canada to be here today.’ The young folk laughed and hurried on. How could these friendly old folk be compared to themselves? Today was theirs. Everyone knew that.

Out of the eighteen students who had graduated in 1947, only eleven had come to the reunion. A few had brought their wives, including Gerald, who had brought Margaret. She was just as excited as the others about the meetings of that day. Later, the celebrating old graduates were to be in for a big surprise, though they didn’t yet know it.

They left the café and headed to the university’s Old College quadrangle, that beautiful, classical-style building designed by Robert Adam. It was a start to bringing back more memories. There they climbed into a minibus and began their journey. Turning along Princes Street, the Scott Monument came into view, rising high and stark to the left of the bus. ‘I once climbed the staircase to the top,’ Ken Runcie boasted proudly, ‘and got a certificate for my pains. But I tell you – I couldn’t do it now.’ Most of the party thought they would not even have attempted the 287-stair climb. They passed alongside Princes Street Gardens, glancing up at the iconic castle, which dominated the city. Next they passed the Usher Hall, where some of them had gone to concerts. On the other side of the road were impressive modern office blocks that the group had not seen before. These were the new symbols of Edinburgh as a financial centre. The bus turned left along the Meadows – perhaps to remind them of a walk home with a girlfriend from an ‘Agri Soc’ dance at the Students’ Union – and then past King’s Buildings, the science campus of the university where so much of their time had been spent as students. So engrossed were these men and women in the journey and the conversations among themselves that they sat up with a jolt when the bus pulled up outside the Dryden Field Station of the Animal Breeding Research Organisation in Roslin, a few miles west of Edinburgh. Gerald Wiener was getting excited, but he restrained himself from reminding the party that this had been his department. Here he had spent hours of his life on engrossing research.

The party was shown into a shed to be faced by a sheep, looking straight at them through the bars of its straw-lined pen. It was as though the sheep was saying hello to a new set of friends. She had become quite accustomed to visitors. All members of the party had heard about this sheep. How could they not? ‘Dolly’ was world-famous as the first mammal in the world to be cloned from an adult cell. And what possible response could there be to a sheep so clearly looking at them? The Canadian glanced wryly at the rest of the group and smiled as he leaned against the pen, saying, ‘Well, hello, Dolly!’

Ian Wilmut (later knighted as leader of the team of this momentous achievement) had been called away at the last moment and was unable to greet the party, but one of his collaborators, Bill Ritchie, was there to welcome the group and talk about the cloning project.

Gerald, as a former colleague of Ian, had been able to arrange this privileged access to Dolly, then just a year old. Visitors were tightly restricted but Dolly was a pampered animal and probably more used to human company than to fellow sheep. Gerald stepped in front of the group to provide an introduction to the occasion.

He had invited his friends on this, the fiftieth anniversary of their graduation, to cast their minds back to 1945 and 1946 when they had learned their animal genetics. The genetics then learned from Hugh Donald, though still relevant today, had changed out of all recognition, particularly the way in which the genotypes of animals can be manipulated and reproduced. This was now a field undreamed of fifty years ago and he wondered with what mixture of enthusiasm and scepticism Donald would have talked about it were he still alive. He then went on to introduce Bill Ritchie, a man at the leading edge of this new animal genetics and in fact the one without whom there might have been no ‘Dolly’. Bill was the man who had performed the intricate microscopic manipulations leading to the birth of the cloned sheep. Bill started by answering the question on everyone’s mind: ‘Why the name Dolly?’

‘The cell from which this sheep was cloned,’ he said, ‘came from the preserved mammary gland of a Finn-Dorset ewe. Dolly Parton, the famous country and western singer, flashed into Ian Wilmut’s mind as someone well endowed in her upper region – it was just an irreverent spur of the moment thought, but the name Dolly stuck’.

On a more serious note, Bill told the interested company that cloning from an adult cell was far more difficult than doing so from embryonic cells, which had been done before. Dolly was the only lamb born from more than 270 attempts where the scientific team had had success. But the purposes for which the cloning was intended required this procedure. It was done in support of other research to produce sheep milk containing human genes that would produce proteins for use in medicines. This, for example, could be used to treat haemophilia. The process of inserting new genes into sheep for their expression in milk was itself extremely difficult and, once achieved, many such sheep would be needed to provide enough milk to be commercially useful. Cloning would therefore be a way of replicating an animal that had the new proteins in sufficient quantity in its milk. There was never a thought that cloning might be extended to humans, as was quickly speculated in more lurid publications – and of course any such extension of cloning for humans was just as quickly banned by governments.

The retired scientists were grateful for being among the privileged few to have seen the famous animal in the flesh. Dolly, still peering through the iron bars of her pen, looked as if she were wishing to say goodbye to her guests, they thought.

Lunch was provided in the splendid Bush House, which had been the mansion house of the large estate that the university had purchased years earlier. Now the house was a centre for final year and post-graduate students, with a good canteen, study rooms and student accommodation. Murray Black, the overall farm manager, still living at Boghall, the original college farm that all the former students had known well, provided the welcome and guided the eager and well-fed party over the estate and its work.

There was one last visit in store that day on the return to Edinburgh. At the grand buildings of the School of Agriculture on the King’s Buildings site of the university, Peter Wilson, Professor of Agriculture and Principal of the College of Agriculture, was there to welcome the former students. They thought back to the old location in George Square where they had studied and were amazed by these seemingly vast premises. But Peter Wilson, sensing the question, explained that there had also been a large expansion in the advisory and investigative functions to the industry for which the college had responsibility and which were also housed in these buildings.

Gerald and Margaret returned with two of the party, Olafur Stefansson and his wife, Thorum, to their home in Biggar where these two Icelanders were staying as guests. Olafur had been one of Gerald’s best friends during their student days. He was also one of a distinguished line of Icelandic men and women who had studied agriculture in Edinburgh, going back as far as 1887. Olafur himself had risen to top roles in Icelandic’s agriculture sector. He became acting Director of Agriculture in Iceland. The two friends had kept in touch by letter for many years after graduation. Apart from Ken Runcie and, briefly, Barbara Findlay when organising the meeting, Gerald had not met any of the party since their graduation fifty years earlier, nor were they to meet again.

After graduation Ken Runcie had become a university lecturer before rising to a top position in the School of Agriculture. Most of the others had gone back to farming lives or moved to other agricultural professions. The Canadian, Andy Lyle, had returned to his own country. Everyone thought it had been a rewarding trip, and an emotional occasion in reliving old memories.

That evening, over a glass or two, Olafur and Gerald and their wives got to talking about the past. Olafur said, ‘Did you ever think your life would work out so well, Gerald, when you were a boy, working as a labourer on a farm and watching every penny that you earned? What a climb you have made! Deputy Director of the Research Organisation, and could have been director, so I’m told!’

Gerald smiled, saying that that had been a situation that arose long ago in his career. He was not a great drinker but the day’s events had got to him and he sipped at his whisky, saying, ‘No, I never did, but it’s all in the past now. It’s been a fascinating life. I’m sure that is true of all us visiting Dolly today. It’s been a wonderful career that I’ve had, and more than that I now have friends and colleagues all over the world, thanks to the University of Edinburgh, and the great teaching, the first-class treatment all we students had. What a privileged lot of people we have been.’

‘A toast!’ said Margaret. ‘To Edinburgh and Scotland!’

‘To England and Oxford!’ said Gerald.

‘To Great Britain!’ said Ólafur.

CHAPTER 2

Berlin Childhood

He was called Horst then, in 1930s Germany. He was in Berlin with his mother. Happily out together for an afternoon’s shopping, they were in the food hall of the KaDeWe, the large department store in the west end of the city. It was December 1936, and Sunday would be his grandfather’s birthday. His mother, Luise Wiener, had taken her little boy there for a special purchase. The whole of the food hall at that time was a feast for the eye. There were counters laden with fruits and vegetables, cheeses and sausages from all over the world. There were coffees, teas, spices and herbs, a butcher’s counter for fresh meat and, best of all for ten-year-old Horst, the large tanks with fish of all sorts swimming around as in an aquarium. He pictured how he might come into sight to these enormous fish as he gazed at them in fascination. One of the creatures flipped its tail as a gloved finger appeared in front of Horst’s face. It was the finger of Liesl (the affectionate, familiar name for Luise).

She had picked out a fine, big carp, her father’s choice as a treat on his birthday. Asking the fishmonger to stun the creature, she explained that it wouldn’t be needed for two days, until the birthday party. He gave the fish a slanted blow to the head and advised her to keep it in cold water in the bath.

Luise took the boy’s hand, having placed the fish, wrapped in a damp cloth, in her shopping bag. Together they started out towards Bamberger Strasse. On meeting a neighbour, Helga Plowdiski, the lady from the stationery shop beneath their flat, they stopped and talked of the forthcoming birthday party. They laughed together as Helga remarked that Herr Trost, Luise’s father, was handsome and that her own mother had a fancy for him. They went on to talk of local affairs, Helga asking about Luise’s family. Horst was getting impatient. He was worried about the poor fish. He longed to get it back to the apartment so that they could put it in the bath, and he tugged at his mother’s skirt, pleading quietly, ‘The fish! The fish!’ Soon Luise relented. The two young women said goodbye.

Luise called back to Helga to suggest that she come up on Tuesday if her mother gave her time off from the shop. They could have some coffee, and Luise wanted to show her some old photographs of Horst when he was younger and of Paul, her ex-husband.

Then Luise and Horst walked on. For twenty minutes they walked past building after building, then up stairs, until the golden moment for Horst arrived and the great heavy carp was released into the cold water of the bath.

On Sunday, Luise’s sister, Erna, and her husband, Erich, arrived with Horst’s cousin, Marion – a good friend and playmate, almost a sister. Both were only children. The fish had gone from the bath, and the children played in one of the bedrooms while the adults talked.

It was a pleasant, spacious flat in the western part of Berlin. The living room opened out with French doors on to a balcony. The overhang from the balcony above shut out a lot of the light and gave the room a somewhat sombre air. The large mahogany dining table with its six chairs stood in the centre, dominating the room. There was a large armchair usually occupied by Grandfather, where he read his newspaper or listened to the radio. There was also a settee – a dark, heavy piece of furniture, but comfortable. In one corner of the room was a large stove, stretching from the floor to just a little short of the ceiling. It was tiled green on the outside and was the principal source of heat for the flat. The warming oven in the upper half of the stove was rarely used. Leading off the living room was Grandfather’s bedroom and another door led onto the passage with the kitchen opposite and two other bedrooms, one for Luise and one for Horst.

The table had been set for the birthday party, the living room cleaned and polished in preparation for the celebrations. The tempting aroma of cooking was everywhere in the apartment. Anticipation of the Sunday meal, special today, was in everyone’s mind, but first the adults had to have their usual discussion of family affairs. These conversations started in a friendly fashion but went up a notch in tone when matters of money were raised. And then there was politics, and the subdued talk of discrimination against Jews and of the frightening stories of concentration camps.

On the evening of the party for Horst’s grandfather, Hermann Trost, one could still hear the sound of raised voices and angry tones. But the children had become used to the voice of irritation from Hermann. Regularly he berated his son-in-law Erich, and regularly he would then turn to his older daughter, Erna, and scold her for the way they spent their money unwisely, such as the expensive-looking outfit Marion was wearing that day.

For a few minutes, the old man’s mind went back to the hard days of the past. Hermann had known tough times in his youth. At the age of fourteen he had walked all the way from Poland, a journey of many days and many nights, seeking work in Germany. After some years of saving his wages he and his wife had set up a drapery and fabric shop in the town then known as Liegnitz in Silesia. (This was before Liegnitz was handed back to Poland after the Second World War and renamed Legnica). The shop became a good-going business. They sold heavy checked cotton material, stuff that would withstand the work in the fields, to farmers’ wives making shirts for their husbands, and finer material for dresses for the wives themselves. Hermann was a good business man. He and Sarah, his wife, scrimped and saved and gradually became successful. Now the old man could not lose his habit of watching his money.

Erna was two years older than Luise. She had married Erich, who was a commercial traveller and therefore had a car – a rare thing in those days. He had fought on the German side in the First World War and was decorated with the Iron Cross for bravery. However, in Hermann’s eyes they wasted their money on fripperies and they had to withstand a lecture every Sunday when they called to see the old man.

The cousins played on, consciously ignoring the angry voices. Always about money. Horst did not remember his father. He remembered nothing of the little town of Kustrin where he was born. One day he would learn the story of how Paul Wiener had met his mother at a dance in the local village. Of how Paul, debonair and wild, had kissed her at the door and she had said, ‘Now you have kissed me, you will have to marry me!’ Well that’s how the story goes. The year was 1924. Luise was very beautiful, slim and romantic-looking in those days as seen from her photographs. Her father was prosperous.

With money from Luise’s father, Paul was set up in a men’s and boys’ outfitters shop in the town of Kustrin in Silesia (now called Kostrzyn and ceded to Poland after the Second World War). The young couple’s shop was several miles away from Luise’s parents’ house in Liegnitz. The Wieners came from Breslau (Wroclaw) originally. Luise’s father’s idea was to give the young couple a start in making a living. But things did not work out. Paul was a natural musician. He played both the piano and the piano accordion very well, and had recently started his own little dance band. He was also very artistic and, in Luise’s eyes, a bit reckless. He liked stunts, some of which were, of course, to advertise their business. One day he brought back a lion cub from a travelling circus to put in the shop window to attract passers-by. Luise did not approve, especially with their baby in the rooms just behind the shop. But more unacceptable than stunts and a preference for his musician life over the shop was the gossip about Paul. Soon after the birth of his little son it became common knowledge that Paul had not one but two girlfriends in the local area. A proper Romeo. Poor Luise was devastated. Soon she had had enough of his nights out and his unfaithfulness. Always out with the orchestra, as he called it. Often seen with glamorous women. His heart and mind were always elsewhere. Horst was only two years old when Luise took him and returned to live with her parents in Liegnitz and help in their shop. She had tried, but in the end, following a period of separation, divorce had to be accepted two years later.

When Luise’s mother died after a short illness, Hermann decided to sell up his business, to move into retirement in Berlin and to take Luise and his grandson with him. On the night of Grandfather’s birthday party, Horst and his mother had been living with him for three years. This was a sadder, quieter way of life for the young Luise, still only in her early thirties. Here in the big city, she did not have to work in the draper’s shop, and she did not have any money worries, as her father was very good to her. She had a woman to do the cleaning and laundry for her, but still she missed having a partner, a husband who would care for her, and love her. It was sad for Luise to feel alone, and sad that her mother, whom she adored, had passed away. But she had her father, and her beautiful son. The boy could be educated in Berlin while she could take care of her ageing father. And Horst was a great comfort and joy to her. Like his handsome father, he had a bright and sunny nature, a dazzling smile, and eyes full of mischief.

CHAPTER 3

Early Schooldays

It was the first day of school for Horst. Along with dozens of boys and girls, he trooped off on the five-minute walk from where he lived, accompanied by his mother. Outside the school was a throng of the young pupils and their doting parents, excited by this special day. As was the custom, each child had been given a large paper cone full of sweets. Each child was cuter than the next; with their brand new clothes and innocent faces they trooped into their classroom carrying their colourful cones. And at this school Horst stayed for two years. But, sadly, this time came to an end when one day Luise was called into the Headmaster’s room.

‘Frau Wiener, we are sorry to tell you that we have been instructed by the authorities that we can no longer have Jewish children in our school.’ The man was clearly embarrassed at having to convey this message, but continued in regretful tones, ‘I will have to ask you not to bring Horst back to this school after today.’

Horst was enrolled in a private Jewish school, the ‘Lessler Schule’, where he continued quite happily, being a bright child and quick to learn. Here he met his first and best friend, Hardy Seidel. They were friends for almost eighty years, close as brothers right up until the time of Hardy’s death in London at the age of eighty-six in 2010. Horst and his cousin, Marion, were like brother and sister. Each Sunday, they met and played together in those carefree years of their childhood, ignoring the rising voices of the adults as the atmosphere in Berlin gradually worsened. They were both sent to a holiday camp one summer, the idea being for them to get a break from their worried parents and to be outdoors most of the day. They were weighed weekly to see if they had gained weight and the one that gained most got a prize. As Horst was always rushing around he was the only child who gained no weight at all.

At home he had his good friend, Hardy. Each day after school they would take their little model cars and race them around the low wall surrounding the fountain at the end of the street. Sometimes they would call at the little newsagent’s shop for pencils and comics. There they chatted with the old lady and sometimes with her daughter, Helga, who were neighbours and friends of Luise.

One day, when the two of them were sitting on the wall of the fountain, silent for a change, Hardy in stumbling tones informed Horst that he thought he would be going away from Berlin quite soon – probably to America. Horst’s heart sank. He listened while Hardy explained that his mother had been so upset and angry when she couldn’t sit down in the park because of the notices that had been put up by the benches saying ‘No Jews Allowed’. It was then that the Seidels decided that enough was enough.

The two boys were silent for several minutes, slowly dealing with their thoughts. Horst’s mind was on his grandfather’s words to his mother: ‘Be quiet, Liesl, you’ll see it will all blow over. I’ve seen it all before.’

Hardy said that his cousin had been attacked by a gang of thugs in uniforms on the corner as he had walked past.

Slowly, it was dawning on Horst that he was about to lose his best friend. Life had been so good, so easy, so sunny. But now the clouds were moving in.

The Seidels did not go to America after all, but took up an offer to go to London instead. Horst’s grandfather, it seemed, helped them a little financially. Hardy’s father had been in a panic about the deteriorating situation around them. He was more politically aware than his neighbours, and the danger signals of each passing day had scared him and they left abruptly. Luise and her father heard from the Seidels in due course. They were doing all right in London, and they urged Hermann Trost to think about moving. But the old man turned a deaf ear. The year was 1937.

Helga Podowski had stories for Luise of her mother’s worry about their little stationer’s shop. Business was very bad. The burly boys of the Hitler Youth had taken to standing outside their premises, stopping people from going in, saying, ‘These are Jews, you know. Don’t give them your money. They have brought all the trouble to our country.’ Another day she came to the apartment on the second floor with tears in her eyes. Her uncle who was a doctor had been told to close down his practice and move somewhere else. No longer were Jewish people allowed to be doctors, or to sell medicines. The poor young woman was close to a breakdown. Luise was scared. Each day she tried to persuade her father to leave Berlin. But it was no use, he would not listen. She began to make her own plans.

As is well known, things got worse and worse for Jews in Germany. There was at this time a dreadful happening, a day never to be forgotten. The residents of their little friendly street were stunned. It was November 1938, the awful Night of Broken Glass, ‘Kristallnacht’. The Nazis had broken all the windows on any shops in the street that were owned by Jews, and painted ‘Jude’ on the doors. This included the little stationer’s shop owned by Luise’s friends. It was a shocked Luise who saw the destruction next morning as she looked out from the balcony of their apartment. Suddenly Horst, now twelve years old, became fully aware of the danger of being Jewish in Berlin at that time. Although they did not attend synagogue, had no kosher rules in the house, and never discussed religion, they were to be outcasts in their own country. It was about then that Luise wrote to the Seidels in London to ask for help. She had heard of the efforts of the Save the Children organisation. She asked if they could get in touch with this organisation to help Horst to escape from the dreadful situation building up in Berlin.

Luise had to carry on with her domestic duties, looking after her son and her father. She had to hide her anxiety from both of them. She had to keep in check the sadness that would come when she had to say goodbye to both of them. At last the papers came through, and Horst was to be allowed to go unaccompanied to Great Britain in what became known as the Kindertransport.

The UK was unique in having agreed to take 10,000 refugee children, and not only Jewish ones, who were in danger of persecution from the Nazis in Germany and other countries in Europe. Homes were to be found for these children – the children on the transports that started in November 1938 and ended in August 1939, just before the outbreak of war. Horst was one of those lucky 10,000. As it turned out, the move of the Seidels to the UK had been a godsend for Horst and, what is more, they helped Luise to escape also.

CHAPTER 4

Goodbye, Berlin

The railway station in Berlin was seething with people. Children, accompanied by one parent, sometimes two, stood in little groups awaiting the train for Hamburg. The unmistakable pounding noise and the smoke and steam of the great engine preceded the appearance of the train. There was the twelve-year-old Horst and his mother among the crowds. Stiff and nervous, like all the other mothers and fathers, Luise tried to keep the tears from her eyes. But the breaking hearts were hard to hide, and the poor young woman kept her handkerchief tightly squashed in her hand as she held the shoulder of her son. This child was her world. He was what she lived for. He had to go, to be sent away from a loving, caring home into the darkness of the world.

‘I will follow you, Horst. Don’t forget that I am coming to England very soon.’ She looked hard into the child’s eyes to make sure he was paying attention. She was like all the surrounding parents, intent on telling their children that they were loved, and that was why they were being sent away. But the boy knew what was going on. He looked at the yellow star on his mother’s sleeve. He knew of the sadness that had descended on their little family already. He was trying to put the whole desperate situation behind him. Horst was projecting himself into a new life, an adventure. He knew that his mother had applied to emigrate to England, and it was almost certain that she would follow him.

Both their lives were now in a fragile state. The febrile atmosphere of children parting from their parents was being repeated that day all over Europe. And time was running out. The whole operation had to be done, and was done inside ten months. Escape was everything; the alternative could not be borne.

The noise in the station increased and the smoke and steam grew thicker as the train filled with children. Innocent and beautiful, full of excitement were the faces that beamed out of the windows of the long train. Hands were waved in goodbye, and handkerchiefs fluttered as the great beast pounded slowly out of the station.

As his mother told Gerald in later years, she returned, empty and dazed, to her father’s home. She felt the shock of leaving her child, and collapsed into her father’s arms, quite unable to speak. Hermann was patient. He was sad for her loss and for his loss too. The child had kept them both going each day. He waited for her recovery silently. Soon he suggested that she should sip some coffee and brandy, and as evening fell, he told of two surprises he had for her. That afternoon he had been to visit a friend of his, Herr Meyer Woolfson, a jeweller in the town.

The old man explained to the jeweller that he wanted something of value that could be hidden in Luise’s clothes – a diamond ring perhaps. Both of the men knew that this would be all that the young woman would have. Only a small, token amount of money was allowed to be taken out of the country by Jews.

And so it was that a ring was chosen. It held a diamond of remarkable purity, of magnificent cut. It was a ring that cost Hermann a good deal of money. The idea was that, in an emergency, it could be redeemed in England. When the deal was done and the ring was stowed away, Hermann’s old friend advised him quietly that he should apply to go to Palestine, saying that he would have no bother to get in with his money. Then it was that Hermann’s voice started to rise in anger, saying that he was a businessman, and that he was not giving all his savings away with the excessively bad exchange rate on offer for his money. In a shaking voice he announced that his money was what he had worked hard for all his life. It was for his retirement. He told the jeweller that he had lost all his first fortune in the years of hyperinflation during the depression. Meyer Woolfson had to listen to this long story, which ended with the old man saying that he couldn’t start up in business again, and that he was too old for the Nazis to bother with him. He was of no use to them, he thought.

That evening, Hermann talked to Luise about her future and how they would communicate with each other when she managed to get away. Their voices became muted and a sadness crept in. She had lived with her father now for years, and cared deeply about him. He and Horst were her family. But she knew she had to be firm in her determination to leave. She had to face facts.

Thoughts of the future rushed through her head. She had been accepted for training as a midwife in Oxford, but not before a medical examination in Berlin, when they had checked that she was of the required weight for the job. Luise was a slight woman and not very heavy so she contrived to put weights in her coat pockets for the weighing and got away with that ruse. Being nearly thirty-six years old, she was too old for full training as a State Registered Nurse, her first choice.

Now Hermann took out the ring. He held it up, explaining that this gift to her was something for her to fall back upon should she run out of money. He told her gruffly to sew it into her coat. Tears were not far from his eyes. She took the ring, and she also felt the tears, never far away, come rushing back to her eyes. The ring, he told her, was valuable, and any honest jeweller would recognise that. Then, turning away, he said that there was something else but since she had had such a hard day it would keep until the next day. She pleaded to be told what else he had to say. The old man shuffled over to the sideboard and produced a letter. He explained that he thought it had come from her sister-in-law, Thea. He recognised the handwriting. Luise was startled. She could not restrain herself from taking the letter. She knew that her ex-husband’s sister, Thea, would not write for nothing. They had been close friends in the past. Thea had loved little Horst as a two-year-old. He would run around wildly, trying to talk and getting the words all strung together and mixed up. Many afternoons the two girls had spent walking in the park with the child, and then meeting up with Paul for coffee and chatter. Paul had also adored his son. He had photographed him endlessly and had made a beautiful album of baby pictures, a book decorated with leaves and flowers, with carefully wrought lettering in coloured inks, all done with great skill and artistry. She had loved that album and gave it to her son who has it to this day.

Luise knew that Thea must have some news of interest to her, and she pleaded with her father to let her read the letter. Shaking with emotion, she retired to her bedroom, the letter clasped in her hand.

Breslau, March, 1939.

My Dear Liesl,

It is a long time since I have written to you, and things here are not good. I am lucky in a way, in that as you know my husband’s name is Haesler and that is not a Jewish name, so they are leaving me alone just now. However, sad to say, my dear brother, Paul, your ex-husband, has been arrested and put in a concentration camp. Tomorrow I go to see if I can visit him. His dance-band has broken up, and people all around are wondering which way to turn. I have one or two friends staying with me who are scared that they will be arrested. They feel safer here in my house.One man I know spent fourteen hours on trains with his fifteen-year-old son, afraid to get off for fear of being caught by the Nazi police.

I will be in touch with you again in a few days when I return from the camp. I hope then to be able to tell you how the land lies. I hope that you and Horst are managing OK in Berlin, and your father is well.

Love from Thea.

On reading the letter, Luise pictured the scenes of those first years of happiness with Paul. Those had been her best times. Those were a few golden days, before Paul went off the rails with women friends and late nights in the dance hall.

The SS Manhattan rose high above the refugee children as they lined up ready to board her in Hamburg that day in March 1939. The boys, maybe about a dozen of them, had gathered in a knot to gaze up at the magnitude of the ship.

They were fascinated by the enormous size of the ship’s funnels. The two large funnels were painted red with their tops in stripes of white and blue. The decks, six of them, were painted white and the hull a shiny black where it hit the blue water of the North Sea. She had provision for over a thousand tourists in cabin, tourist and third class. It was a luxurious liner, built to carry wealthy tourists to and fro across the Atlantic. But on this day, the passengers were hundreds of refugees leaving Germany, eighty-eight of them children, almost all of them travelling unaccompanied, overseen by the Save the Children organisation. Horst was in the most excited state of his young life. The parting from his mother now behind him, he decided that this was to be a great adventure. Somehow he had developed a capacity to put unpleasant thoughts and bad experiences behind him, and this skill was to stay with him for the rest of his life. However, he would later discover that they were always there when his memory was jolted.

It was a beautifully decorated and furnished ship, and except for the youngest children who seemed a bit dazed and unsure, the young refugees were thrilled with their experience. The crew were kind and welcoming to them. They each exchanged their one Deutsche Mark for English money. Horst was sick at the time of the money changing, and was lucky enough to receive a penny more than the others. They were each given fruit, drinks and sweets, and balloons were hung around their quarters. Games were organised so that it was almost a party atmosphere.

The SS Manhattan was bound for New York, her home port. On this voyage, the ship was scheduled to stop at Le Havre in France and Southampton in England before crossing the Atlantic.

When the ship docked at Le Havre in the early hours of the morning, the older boys, hugging the rail, were dumbfounded to see a great eagle sculpture on the quayside that looked like a Germanic symbol. For a few minutes they thought they had returned to Germany, and fear was on their faces and in their hearts. But it was found to be a false alarm, and they were soon sailing on their way to the south coast of England, and the welcome sight of the white cliffs of Dover.

CHAPTER 5

New Beginnings

Horst, along with several other children, was taken to a hostel on the coast in the south of England, near Margate, where, although the children were safe and looked after, they always complained of feeling hungry. The hostel must have been short of money and did its best. After a week or two the children were given pocket money. They spent hours deciding on the best way to spend their three pennies a week. The favourite purchase was chewing gum because it lasted longer.

Horst would lie in bed at night thinking back to the wonderful visits to the Kurfürstendamm, the fashionable street in the centre of Berlin, bustling with coffee houses. The wonderful aroma of the coffee drifting from every café and the sound of little orchestras playing the music of Strauss came back to the boy as he lay in his narrow bed. It had been one of his grandfather’s treats for himself and his cousin, Marion, to go into a favourite café. There they had the thrill of being allowed to go to the marvellous cake counter to choose a cake for themselves. It was a lost magic.

He remembered wonderful Saturdays strolling in the Tiergarten, sometimes visiting the zoo to see the lions and tigers. How he and Marion had screamed with excitement on those sunny days with their grandfather. How was she, and how were her parents? They must be trying to leave Berlin. Marion would be fourteen now. Did she remember those times at the KaDeWe department store, where they went some Saturdays? That was their favourite outing. How he wished he could be there to see that food hall again – the colours, the smells of food, of coffee, and seafood and the fish swimming in the great tanks.