13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

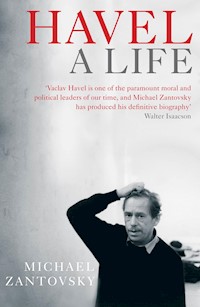

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This startling biography explores the remarkable life of an iconic figure of the twentieth century, Václav Havel, author and dissident, who became the first president of the Czech Republic. Vaclav Havel: iconoclast and philosopher king, an internationally successful playwright who became a political dissident and then, reluctantly, a president. His pivotal role in the Velvet Revolution and the modern Czech Republic makes him a key figure of the twentieth century. Michael Zantovsky was one of Havel's closest confidants. They lived through the revolution and during Havel's first presidency Zantovsky was his press secretary, speech writer and translator. Their friendship endured until Havel's death in 2011, making him a rare witness to this most extraordinary life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

‘[Zantovsky] puts his words lightly on the page and allows them to merge into pictures.’ Irish Independent

‘…this huge book is a labour of love that doesn’t flinch from describing the complexes that made life difficult for Havel and those around him… A contemporary hero perhaps has to be in the mould of Hamlet…There can’t be a last word for someone like that, but this book comes as close to it as possible.’ Literary Review

‘Zantovsky was an elegant writer before he turned diplomat and this is a clear-eyed portrait that never descends into gush or hagiography…Zantovsky’s account of the velvet revolution is masterly.’ Victor Sebestyen, The Spectator

‘…the magnificent new biography by Michael Zantovsky’ Standpoint

‘Zantovsky’s talents as a diplomat, not to mention his gifts as an observer and writer, are apparent in this beautifully written biography. To tell the story of the man who made “living in truth” his motto you must tell the truth about him and Zantovsky sets about the task with exquisite politeness and also with genuine love for the person whose faults he describes the better to show the greatness that transcended them… He tells the story with a flair for detail, almost as though he had stood at Havel’s shoulder, taking notes’ Roger Scruton, The Times

‘A sympathetic, well-documented and highly readable account…[Zantovsky] is a fine storyteller; and there is a great story to be told…This Life comes closer than any previous attempt to do justice to an extraordinary destiny which led Václav Havel from dissidence to the Castle – and back again.’ Jacques Rupnik, TLS

‘Micahel Zantovsky’s Havel is the authoritative biography of a great man, a true artist and a flawed character, by someone who shared Havel’s dissident background, and who writes of him with real insight and love…Zantovsky is as intelligent and subtle as his subject, and his book an unforgettable tribute’ Roger Scruton, TLS Books of the Year

‘Michael Zantovsky’s biography of Vaclav Havel is a joy and an inspiration. Warm, wry, witty, it tells the life story of one of the greatest thinkers, writers and politicians of our time… Zantovsky has paid his friend the ultimate compliment of not writing a hagiography but a superbly nuanced biography which will never be equalled.’ William Shawcross

‘As Havel’s close friend and collaborator for nearly 30 years, Zantovsky helps us admire and understand this philosopher king whose summons “Power of the Powerless” gave courage and hope to people around the globe.’ William Luers, former US ambassador to Czechoslovakia

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Michael Žantovský, 2014

The moral right of Michael Žantovský to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 852 4

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 851 7

Extract from ‘An Arundel Tomb’ © Estate of Philip Larkin and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd; Extract from ‘Annus Mirabilis’ © Estate of Philip Larkin and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd; Extract from ‘August 1968’ © Estate of W. H. Auden and reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd; Extract from ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’ © Estate of W. H. Auden and reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For David, Ester, Jonáš and Rebeka

All my life I have simply believed that what is once done can never be undone and that, in fact, everything remains forever. In short, Being has a memory. And thus even my insignificance – as a bourgeois child, a laboratory assistant, a soldier, a stagehand, a playwright, a dissident, a prisoner, a president, a pensioner, a public phenomenon, and a hermit, an alleged hero but secretly a bundle of nerves – will remain here forever, or rather not here, but somewhere. But not, however, elsewhere. Somewhere here.

Václav Havel, To the Castle and Back

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE

18 DECEMBER 2011, A DARK COLD DAY

BORN WITH A SILVER SPOON

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A VERY YOUNG MAN

THE SILVER WIND

GOOD SOLDIER HAVEL

OLGA

THE APPRENTICE

THE GARDEN PARTY

THE SIXTIES

A PRIVATE SCHOOL OF POLITICS

THE MEMORANDUM

THE GATHERING STORM

SCOUNDREL TIMES

MOUNTAIN HOTEL

ROLL OUT THE BARRELS

THE BEGGAR’S OPERA

IT’S ONLY ROCK ’N’ ROLL

THE CHARTER

THE MISTAKE

THE GREENGROCER REVOLT

THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

THE TRIAL

DEAR OLGA

FREE AT LAST

THE PRAISE OF FOLLY

THE BATTLE FOR WENCESLAS SQUARE

THAT VELVET THING

THE FOG OF REVOLUTION

THE ROAD TO THE CASTLE

THE BAG OF FLEAS

THE PRESIDENT OF ROCK ’N’ ROLL

FIRST WE TAKE MANHATTAN

THEN WE’LL TAKE THE KREMLIN

THE INNOCENTS ABROAD

MAKING THE FISH

THE END OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

WAITING AS A STATE OF HOPE

THE BONFIRE OF SCRUPLES

IN SEARCH OF ALLIES

BACK TO EUROPE

THE YIN AND THE YANG

BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH

THE UGLY MOOD

FAREWELL TO ARMS

PAROLED

LEAVING

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

Božena Havlová and her sons. Family archive.

2.

Good soldiers Havel. Family archive.

3.

Silver wind. Family archive.

4.

The young artist in his den. © Erich Einhorn.

5.

With Olga at Café Slavia. Family archive.

6.

Private view in the basement of Kohout’s country house. © Oldřich Škácha.

7.

‘The Last Supper’. © ČTK/Jiří Bednář.

8.

The mysterious dude. © Jaroslav Franta.

9.

The Plastic People of the Universe. © Ondřej Němec.

10.

The Founding Father. © Dagmar Havlová-Ilkovičová.

11.

The spokespersons of Charter 77. © Ondřej Němec.

12.

Václav and Olga. © Oldřich Škácha.

13.

Comrade Havel. © Jan Kašpar.

14.

Prison Mugshot. Public domain.

15.

Hrádeček and Lunokhod. © ČTK/Jiří Bednář.

16.

The brewery worker. © ČTK.

17.

The spokesmen of Charter 77. © Ondřej Němec.

18.

Free at last. In the Pod Petřínem hospital. © Jaroslav Kukal.

19.

International Human Rights Day rally at Škroupovo Square. © Joel Robine/AFP/Getty Images.

20.

The birth of the Civic Forum. © Jaroslav Kořán.

21.

‘We have not met yet, have we?’ © ČTK/Libor Hajský.

22.

‘Truth and love must prevail over lies and hatred!’ © ČTK.

23.

United we stand. © ČTK/AP/Dusan Vranic.

24.

Re-elected. © Karel Cudlín.

25.

Without the goose step. Reviewing the honour guard. © ČTK/Karel Vlček.

26.

The president and his spokesman. © Oldřich Škácha.

27.

At breakfast. © ČTK/Libor Hajský.

28.

Speaking to the joint session of the US Congress. © ČTK/Jaroslav Hejzlar.

29.

Goodbye to red ties. © Vitaly Armand/AFP/Getty Images.

30.

The Stones in the Castle. © ČTK/Michal Doležal.

31.

Communist leader Antonín Zápotocký makes room for Winston Churchill. © ČTK/Michal Kalina.

32.

The federal conundrum. © ČTK/Stanislav Peška.

33.

The abdication. © ČTK/Michal Krumphanzl.

34.

With Tom Stoppard at the Czech premiere of Travesties. © Ondřej Němec.

35.

‘Welcome, Your Holiness, among us sinners.’ © ČTK/Martin Gust.

36.

‘Ma’m, let me present Gyula.’ © Alan Pajer.

37.

Dancing with Hillary. © Alan Pajer.

38.

With Bob Dylan and Dáša. © Alan Pajer.

39.

The presidents and the first ladies, Madeleine Albright and author. © The White House.

40.

‘The man of my life.’ © Ivo Šilhavý.

41.

With the Dalai Lama. © ČTK/Michal Kamaryt.

42.

The premiere of Leaving. © Alan Pajer.

43.

The Mourning. © ČTK/René Fluger.

44.

A step too far. © Tomki Nemec.

PROLOGUE

THREE QUESTIONS SHOULD BE ASKED, at least implicitly, and answered, at least tentatively, before another small forest of trees falls victim to the idea of writing a book. Is the subject of any interest to anyone but the author? Have there been other treatments of the subject, which could satisfy such interest? Is the author the right person to write about the subject?

Václav Havel was one of the more fascinating politicians of the last century. His unique riches-to-rags-to-riches life story is easily given to simplistic accounts, but there is no doubt that he played a prominent role in finally putting to rest one of the most alluring utopias of all time, and oversaw one of the most dramatic social transitions of recent history.

Although many people, including Havel himself, often marvelled at the fairy-tale nature of his sudden elevation to the highest job in the country, there had been in fact nothing miraculous or accidental about it. As this book will aim to show, the ambition to ‘repair the world’ had been present in Havel’s life ever since, at the age of ten, he envisaged a factory manufacturing ‘good’ rather than goods. Equipped with a hypertrophied sense of responsibility that led him to stand his ground and persist in the face of adversity, and with the less than conspicuous but all the more real discipline and industry with which he applied himself to the tasks at hand, he emerged in November 1989 not just as the most likely, but as the only plausible candidate for the leader of the revolution.

Even so, Havel cannot be simplistically reduced to a dissident or politician. He was also a formidable thinker, who consistently attempted to apply the results of his thinking process, as well as the moral precepts, which were at its core, to his practical engagement in the realm of politics. Some would question whether he was an original thinker of lasting significance. Although well read, he lacked the formal education, broader erudition and systematic discipline of a real scholar, and he was often wont to remind his readers and listeners of this handicap. His moral philosophy can be reduced to three concepts, which are inseparably linked to his name. The first, the ‘power of the powerless’, also the title of his best-known essay, is almost slogan-like in its simplicity. It makes for a great rallying cry, but at first sight it appears not to be applicable to most day-to-day situations, where power rests with the powerful, and the powerless are just that. Paradoxically, it is even harder to apply when the powerless suddenly find themselves in positions of power. And yet, this concept found an indelible expression in perhaps the only revolution in history that left no victims. The second, ‘living in truth’, has an almost messianic tinge, and exposes its author to charges of being starryeyed, hypocritical or worse. By most ordinary definitions of ‘truth’, Havel can sometimes be caught in contravention of his own teaching, and yet few can fault his determination to live up to the principle as best he could. The concept of ‘responsibility’, rooted in the ‘memory of being’, completes the triad. The rest, as they say, is commentary. Havel left behind no comprehensive work, and no formal philosophical system. In some of his metaphysical thinking, especially during his presidential days, he balances perilously on the brink of new-ageism and pop philosophy. For the most part, however, there is a crystal-like moral clarity and consistency to his thought.

Next to, but not second to his role as dissident, politician and thinker, Havel was a wonderful, witty and original writer. His success in that arena owed nothing to his public status and renown as a dissident or a politician; in fact, it came into play a long time before he became the best-known Czechoslovak prisoner of conscience, and an even longer time before he became a president. Quite to the contrary, it could be argued that Havel’s public career imposed severe constraints on his writing. The high points of his creative work came in the mid-1960s with plays like The Garden Party (1964) and The Memorandum (1965). Although never embraced by the Communist art commissars, Havel enjoyed considerable artistic freedom and numerous opportunities during this period. Leaving (2008), his last play, begun before he embarked on the presidency and finished only after he left it, is a telling reminder of his writing potential. The intervening period contains little gems, such as the one-act plays Audience (1975) and Private View (1975), powerful moral dramas like Temptation (1985), intriguing exploits like The Beggar’s Opera (1972) and Largo Desolato (1984), and some arguable failures like Conspirators (1971) and Mountain Hotel (1976). The two autobiographies masked as interviews with Karel Hvížďala, Disturbing the Peace (1986) and To the Castle and Back (2006), attest to both Havel’s unique power of introspection and his subversive humour. His prose writings at the height of his dissident era, including some of his most memorable essays and the unique piece of epistolary work that is the Letters to Olga, are hybrids of creative writing, philosophy and political prose, best appreciated in the context in which they were written; nevertheless, some of these have clearly passed the test of time and changing circumstances.

Finally, there was Havel the person, someone who achieved his impact on others through means as unique as was his life. From his teens onwards, he was a leader, setting agendas, walking at the front, showing the way. Yet none of this was in any way associated with the monomania of a true visionary, but was conducted rather with a diffidence, kindness and politeness so unwavering (and often unwarranted) that Havel himself caricatured it in some of his plays; moreover, these traits were graced by an all-encompassing sense of humour and the absurd, which was mostly kind, sometimes wicked, but never cruel. A man thriving on company, the heart and soul of the party, winning friendship easily and returning it in abundance. A lovely man, the English would say.

Still, there was the other Havel, ‘a bundle of nerves’,1 depressed, ill, raging at his own impotence, escaping into drink, prescription drugs, sickness and sometimes ill-considered sexual adventures. His confidence never wavered when he stood at the head of millions and pondered the possible crackdown by tanks surrounding Prague in November 1989. Yet when he did become president, with all the trappings of power, he was rarely sure he was up to the task; by his own admission he became suspect to himself. Trying to live in truth, he measured himself, though never others, by this impossibly high standard and by his own judgement he invariably failed. An imperfect man, like the rest of us.

The only way to explain and understand Havel’s enormous and lasting popularity and significance – as the aftermath of his death made plain – is thus to consider not just the individual areas of his work and activity, fascinating and valuable as they are, or to explore the individual aspects of his complex personality, but rather to see how the pieces fit together in a coherent, enduring and mutually reinforcing, though paradoxical, whole, which was so much greater than a sum of its parts. He was the ultimate WYSIWYG, authentic, genuine, real in a way most people can only aspire to and most politicians would kill for. Even his flaws were real, not the peccadilloes of some media-concocted caricature of a celebrity.

As it happens, there exist several previous biographical studies of Havel from various perspectives and angles, in Czech, in English and in other languages, all – with one exception – written before Havel’s death.2 They all contain valuable insights into multiple aspects of Havel’s life, work and personality. Obviously, they are fragmentary: no account of a life can be complete until that life is over; but they are also fragmentary in the sense of focusing on a particular component of the Havel myth, be it his lifelong perspective as an outcast and rebel, his ambivalent attitude to politics in general – and to his presidency in particular – his moral philosophy, his artistic creativity or his free-wheeling lifestyle. That said, there is of course no such thing as a definitive biography, and this work is therefore destined to be regarded as a mere stepping stone on the path towards discovering the true Václav Havel.

Finally, why me? I was close to Václav Havel but I could not claim to be the closest person to him, or to have known him the longest. I knew of him for two thirds of his life, but knew him well only for the last third. We were close for most of that time, but due to the vagaries of the very history he had helped to make, and the obligations that it entailed for both of us, we did not see each other for long periods at a time. In fact, one of the mysteries of Havel – and one on which this book can only shed some partial light – is who really were the people closest to him. Apart from his two wives, and his brother Ivan, who between them comprised the family he had as an adult, and perhaps the late Zdeněk Urbánek, who alternated between the roles of Havel’s alter ego and superego, there were a large number of people with whom Havel was intimate, and yet there was no one who could claim to be his closest friend without being challenged for the title. There was, mixed with the warmth and the friendliness, a certain remoteness to his personality, a sense of detachment, an inner impenetrable core that you could never enter.

This also accounts for a certain asymmetry in Havel’s personal relationships, including our own. No matter how important various people were to him at various times, there was always the sense that they needed him more than he needed them. There was, as far as I could tell, no deliberate effort on his part to dominate or to engage in one-upmanship. On the contrary, he tended to be modest to a fault, self-deprecating, even apparently submissive towards friends, and yet he somehow always came out on top. I believe that this was the secret key to his unique but strangely effective leadership style, and for that reason I will deal with it at more length later in this work.

There is no question that Havel and I felt good in one another’s company, and that we shared many laughs, moments of sadness, quite a few drinks and some incredible moments together, both before and after he became president. My proudest moment with him was not when the two of us ‘jointly’ addressed the joint session of the US Congress as I will describe later on, or when he presented me to the Queen. Instead, it was when he allowed me to carry his personal effects in a string bag on 17 May 1989, as he emerged from the side entrance of the Pankrác prison on his release from his last imprisonment.

During the first two of his four terms as president (from 1989 to 1992), I probably spent more time with Václav Havel than any other person, including his wife. This was not a mark of my importance, but of the nature of my job: as his spokesman and press secretary I had to be present at each foreign trip, each fruitless appointment and each forgettable function, so as to be able to report about it later to the press on behalf of a president who did not particularly enjoy media attention.

I had tremendous respect for his ideas, his sincerity, his unflappable kindness, his authenticity and his courage. Even so, that did not always lead me to agree with him, both about the practical decisions he had to make as president and the philosophy underlying them. Part of my job was to play the advocatus diaboli, and to make the case for doing things differently or for doing different things or, indeed, for not doing some things at all. Occasionally – though not very often – I prevailed. That in turn led to my appointment to a parallel role as political coordinator of the president’s office, a problematic elevation, as it came with no specific powers, and its authority was largely unenforceable in a team of friends.

Over time our differences increased, not in terms of our goals, our view of the world or our role in it, but in terms of the practical conduct of the presidency. Rightly or wrongly, I felt that he would find it more and more difficult to have a real impact on the political and social developments of the country unless he organized the large numbers of his supporters and admirers into an effective political force, or let them organize themselves. He respected the argument and largely shared the analysis, but in the end he would rather live with the handicap of not having a political machine than enter the arena of factional politics. This was something that I had to respect for my part. Nevertheless, it was a major reason for my departure from the president’s office at the end of Havel’s second term, even though I was invited to stay on. Over a couple of drinks in the spring of 1992, Havel graciously accepted my reasons for leaving and threw his full weight behind my next career move, the ambassadorial appointment to Washington. He never ceased to be supportive of me, and continued to be generous with his time and friendship, across three continents, and whenever the occasion arose.

My own relationship to Havel can best be described by a word that I use with the utmost reluctance. But if love means not just liking another person and enjoying his company, but caring for him, worrying about him, dwelling in one’s thoughts with him over considerable distances and periods of time, and being keen on his approval and reciprocation, then love it was. I suspect I was not the only person in Havel’s inner circle who would define his or her relationship to him in this way. It was this bond that kept us together, and kept us going during the crazy early days of Czechoslovakia’s democratic transformation.

Being in love with the subject of one’s biography is not necessarily the best qualification for writing it, for it brings with it the risks of hagiography, lack of perspective and distortion of facts. While I am not sure I can successfully navigate my way around these perils, largely hidden underwater, I could do worse than to fall back on my original profession as a clinical psychologist. One less enjoyable but essential aspect of that and other medical professions is the ability to assume a ‘clinical posture’, i.e. the skill to watch other human beings, including people closest to you, struggle, triumph, decline, suffer and die, all the while taking dispassionate notes of the experience. The result is for the reader to judge.

1

To the Castle and Back (Prosím stručně). Translated by Paul Wilson (London: Portobello Books, 2008), 330.

2

The three most interesting, in this author’s view, are Carol Rocamora’s Acts of Courage: Václav Havel’s Life in the Theater, Martin C. Putna’s Václav Havel: A Spiritual Portrait in the Framework of the Czech Culture of the Twentieth Century and Jiří Suk’s Politics as Absurdist Drama, Václav Havel in the Years 1975–1989, the last two unfortunately only available in Czech. Three general, though incomplete biographies, Eda Kriseová’s Václav Havel, The Authorized Biography, John Keane’s Václav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts and Daniel Kaiser’s Dissident, Václav Havel 1936–1989, are also worth reading for their wealth of detail and for interesting, albeit sometimes disputable perspectives. This author was grateful to be able to draw on all of them.

18 DECEMBER 2011, A DARK COLD DAY

He disappeared in the dead of winter:

The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted,

And snow disfigured the public statues;

The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day.

What instruments we have agree

The day of his death was a dark cold day …

– W. H. Auden, ‘In memory of W. B. Yeats’

IT WAS A WINTRY SUNDAY MORNING in Prague on the last weekend before the Christmas holidays. Most people’s thoughts revolved around wrapping up their Christmas presents and perhaps getting some rest. It had not been a particularly happy year. Although the country was faring better than most in the midst of a European debt crisis, the economy was slowing down, and the austerity measures were beginning to bite.

The news, when it came, first on the social networks, and soon through the general media channels, came as a shock, although it ought not to have. The whole nation had known that the ex-president was ailing. Since the spring, his friends had been aware how serious his condition was. This was not the result of any acute ailment, but rather a progressive general exhaustion combined with a sudden loss of the will and the fighting spirit that had characterized him for most of his life.

If there was no sustained public interest in Václav Havel’s condition, no media deathwatch outside his house, it was simply because the ex-president appeared to be old news, no longer relevant to current events and issues. He was still a subject of moderate interest to cultural and literary editors because of his recent creative exploits, and his name sometimes appeared next to his wife’s in the celebrity pages. The house at Hrádeček, where he had been spending his last months, was a hundred miles away from Prague on a bad country road, with few hotels or restaurants nearby. To the media hounds, it was hardly worth the trouble.

Prime Minister Petr Nečas, appearing on a Sunday television talk show at the moment the news broke, was the first to respond publicly. ‘His death is a great loss,’ he said respectfully. Still nothing suggested more than a few days of polite mourning for a figure from the past.

Shortly after noon, people started to bring flowers and candles to the Castle and to lay them at the perimeter fence. Flowers and candles also appeared around the house at Hrádeček. Some good soul left two bottles of beer from the brewery in Trutnov, which had inspired Havel to write Audience.

At 2 p.m., Havel’s successor as president chimed in. ‘Václav Havel has become the symbol of our modern Czech state,’1 said Václav Klaus. No one expected him to be ungenerous at that moment, and yet there was something remarkable in this sweeping eulogy by a man who disagreed with Havel on so many day-to-day issues of Czech politics.

A crowd began to gather spontaneously on the square under the statue of St Wenceslas, where the demonstrations had begun in 1989. People stood and rattled their keys, just as they had in November 1989. A group marched to the river, taking the same route as the student demonstration on 17 November, which set off the Velvet avalanche, but in the opposite direction. The marchers paused at the plaque honouring that seminal moment in Czech history. Some left packs of cigarettes.

There were few overt expressions of grief, no rending of garments, no hysterics. When, ten weeks later,2 Sir Tom Stoppard paid Havel the tribute of quoting John Motley’s eulogy of William of Orange, ‘As long as he lived he was the guiding star of a whole brave nation, and when he died the little children cried in the street,’3 he himself admitted to ‘sentimental hyperbole’.4 The feeling was that of a communal memory, of remembrance and, yes, of celebration. There were gatherings in other towns and cities throughout the Czech Republic as well.

One could not help ponder the contrast with another kind of mourning half a world away. Kim Jong Il, the Dear Leader of North Korea, died just the day before. There, W. H. Auden’s paraphrase of Motley’s words was irrefutably apt: ‘When he laughed, respectable senators burst with laughter. And when he cried, the little children died in the streets.’5 The Korean state news agency aired footage of huge columns of people wailing in unison. No doubt, many of the 200,000 political prisoners in the country were crying as well, though theirs were tears of joy.

Condolences started to come in from abroad, some official, from heads of states and governments, others from friends, former dissidents and writers. Russian state TV contributed a eulogy of its own: ‘Václav Havel was the main driving force of democratization in Czechoslovakia, and the grave-digger of the advanced Czech arms industry, whose demise was one of the causes of the break-up of Czechoslovakia.’ A balanced assessment, straight from The Garden Party.

The spokesman for the Association of Czech Travel Agencies managed to see the bright side. ‘For a long time the Czech Republic had not been as visible as this,’ said Tomio Okamura, who would announce his own candidacy for president just a few weeks later. ‘In winter people are deciding about where they will go for their summer vacations, and although Havel’s demise is a sad thing, it is a very good advertisement for the country.’6

On Monday, in what was still a family affair, Havel’s remains were brought to Prague in a simple casket, and laid in state at the Prague Crossroads, the Gothic church that he and his wife Dagmar had restored and turned into a cultural shrine and meeting place. For the next two days and throughout the night, people lined up to pay their respects. The government declared a state of mourning. The government of Slovakia, a country that at one time seemed to have repudiated Havel, did the same.

On Wednesday, the state took over. The casket made its journey across the river and up the hill to the Castle, followed by thousands of people. In the Castle Guard Barracks it was loaded on the same gun carriage that had been used for the funeral of the first Czechoslovak president, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, and carried to the Vladislav Hall in the Prague Castle, the fifteenth-century seat of coronation ceremonies, and the venue of Havel’s first election to the presidency. Once again Klaus was up to the task: ‘Our Velvet Revolution and the era of restoration of freedom and democracy will always remain associated with his name. More than anyone else, he deserves the credit for the international standing of the Czech Republic, its prestige and its authority … As a writer and playwright he believed in the power of the word to change the world.’7

Friday, 23 December, the day of the funeral, was also the last day before the traditional start of the Czech holiday season on Christmas Eve. Despite the inconvenient timing, government planes started landing in quick succession at Prague’s Ruzyně Airport, soon to bear the deceased’s name. In what seemed an unending procession of black limousines, their passengers, eighteen heads of state and government and other dignitaries, including President Sarkozy and Prime Minister Cameron, Hillary and Bill Clinton, Madeleine Albright, Lech Wałęsa, John Major and Prince Hassan of Jordan, proceeded to the St Vitus Cathedral at the Prague Castle, where they joined around two thousand Czech government officials, friends and family.

In a familiar dilemma, I found myself torn between the need to mourn freely for a friend and the duties of the ambassador to the Court of St James’s, which included being on the tarmac to greet the current and former British Prime Ministers. I knew I could never make it to the cathedral in time for the ceremony, for the prime ministers were late, and their motorcade was leaving airside straight from the tarmac, while my driver was waiting kerbside half a mile away. Without a police escort, which only the motorcade had, I would never make it through the security checks in time for the ceremony. The secret servicewoman in charge coldly vetoed my plea to piggyback on the motorcade. Trying to think what Havel would do, I jumped into the already moving limousine of Sian McLeod, the empathetic British ambassador to Prague, before the secret servicewoman could speak a word into her jacket sleeve. I slipped into my seat at the cathedral with the first notes of music.

Just as Havel, a non-denominational believer, was honoured at his election by the Te Deum mass, he was now treated to a Catholic mass, accompanied by Antonín Dvořák’s Requiem. Josef Abrhám, who played Chancellor Rieger in the film version of Leaving, read Dies Irae, words that uncannily reflected Havel’s own thinking:

Great trembling there will be

when the Judge descends from heaven

to examine all things closely.

The trumpet will send its wondrous sound

throughout earth’s sepulchres

and gather all before the throne.

Death and nature will be astounded,

when all creation rises again,

to answer the judgement.

A book will be brought forth,

in which all will be written,

by which the world will be judged.

Havel did not die a Roman Catholic, and during his last days he never asked for the last rites, but his sense of theatre and ritual would have been gratified by the liturgy, celebrated by his fellow prisoner Cardinal Duka, and by the procession that preceded it. He would have enjoyed, albeit with some embarrassment, hearing the praise from friends, Madeleine Albright, his fellow Velvet revolutionary, Bishop Václav Malý, and Karel Schwarzenberg.

For the third time, the president spoke, this time on Havel’s spiritual legacy, embodied in the ideas that ‘freedom is a value worth sacrificing for’, that ‘it is easy to lose freedom, if we care little about it and do not protect it’, that ‘human existence extends into the transcendental realm, of which we should be aware’, that ‘freedom is a universal principle’, that there is ‘tremendous power in a word; it can kill and it can heal, it can hurt and it can help’, that ‘it is able to change the world’, that ‘the truth should be said, even if it is uncomfortable’ and that ‘minority opinion is not necessarily wrong’.8 There were many words of praise that day, but these may have weighed more than most, simply because of the man who uttered them.

While the heads of states and foreign dignitaries attended a reception given by the president, family and friends, myself among them, were making their way across town to the funeral hall of the crematorium in Strašnice for a last goodbye. Unlike in the cathedral, the speeches here were numerous, improvised and mostly heartfelt, though forgettable. Some of the closest friends chose not to speak at all. It was as much a chance to say hello to the others present as to say goodbye to the one who was gone. Then the curtain fell.

There was still a third act to follow, an evening of music, performance and entertainment, to honour Havel the bohemian intellectual, the rock ’n’ roll aficionado and the chief of an Indian nation, a title awarded to him by an open-air rock festival in Trutnov. It took place in the Lucerna Hall, the house that Havel’s grandfather built. The last number on the bill belonged to the Plastic People of the Universe, a band that had played an influential role both in Havel’s life and in Czech history.

It was an amazing week, a week of mourning a loss, and a celebration of a great find, or perhaps a rediscovery. People emerged from ‘the cells of themselves’,9 and at least for a while forgot about the coming winter, the thousand necessities of a family Christmas and the uncertain perspectives ahead. They joined in a rite of mourning and respect, were nice to their fellow men and spoke kindly of their enemies. In this strange mixture of sadness and joy, the latter seemed to have prevailed, joy at being confronted with greatness. Havel would have disliked that word. He would have been a little embarrassed by it all, and his comments would reflect a combination of modest pleasure with subtle irony, and a sense of wonder about a nation that he sometimes said was capable of the most amazing feats of dignity, solidarity and courage, if only for a couple of weeks once every twenty years.

1

Statement by the President of the Czech Republic Reflecting the Death of Former Czech President Václav Havel, 18 December 2011, http://www.klaus.cz/clanky/3002.

2

Remembering Václav Havel, RIBA, London, 1 March 2012.

3

John L Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic (EBook #4811 Project Gutenberg, 2012).

4

Remembering Václav Havel, RIBA, London, 1 March 2012.

5

‘Epitaph on a Tyrant’ (1940).

6

‘Václav Havel died December 18, 2011’, www.lidovky.cz, 19 December 2011.

7

Speech by the President of the Czech Republic at the solemn gathering to honour the late President Václav Havel, 21 December 2011, http://www.klaus.cz/clanky/3005.

8

Speech by the President of the Czech Republic at the Funeral Service in St Vitus Cathedral, 23 December 2011, http://www.klaus.cz/clanky/3007.

9

W. H. Auden, ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’.

BORN WITH A SILVER SPOON

MYTHOLOGIES MATTER. In retrospect, it seems hardly accidental that the first-born son of a prosperous Prague family, which epitomized in miniature the achievements of a newly independent nation with an ancient history, received his name after the patron saint of Bohemia. Nor does it seem accidental that by virtue of his birth and name he became heir to a dynasty. Just as St Wenceslas,1 the tenth-century Premyslid duke, came to be followed by three kings of the same name, the founder of the Havel dynasty, an entrepreneurial miller’s son and part-time spiritualist, Vácslav Havel, gave his name to his son Václav Maria, who in turn did the same, on 5 October 1936, for his own son, the future president. The mythology does not end there, for the legendary treatment of the historical St Wenceslas constitutes a direct equivalent to the Arthurian tale, possibly with the same antecedents. Not far from Prague there is a hill called Blaník, conceivably a sister knoll of Planig in the Rhineland, Blagny near Dijon and Bligny near Paris, all of them with Celtic roots, inside which an army of knights is said to be sleeping and waiting for the moment when things could not be worse for the Czech nation, at which point, under the command of St Wenceslas himself, they will come to its rescue. Anybody using the name for the third time in as many generations must have aimed high.

There were good reasons for such ambitions. Starting from scratch with a small town sewerage project, the eldest Havel had built a construction and property empire, which included the proud townhouse on the banks of the Vltava River where the family lived; nevertheless, his crowning achievement was the big commercial and entertainment complex called Lucerna on the conveniently named Wenceslas Square, at once the Piccadilly and the Champs Elyseés of the bustling town. The first edifice built of reinforced concrete in the city, it was dubbed ‘Palace’ at the time, but with its dance hall, shops, bars, a cinema, a music club and numerous offices it might today be called a mall. Prague is not a city the size of New York or London, but neither is it a small town, and so the regularity with which the above places and symbols crop up time and again in the story of Václav Havel’s life is quite remarkable.

Vácslav’s two sons were no slouches, either. Václav Maria followed in his father’s footsteps and expanded the construction and property business, although he was hard hit by the Great Depression in the early 1930s. Inspired as a young man by his trip to California, he conceived of an exclusive property development on the Barrandov Hills above the Vltava River, hired the foremost modern architects to build the first flat-roof, functionalist villas there, so unlike the typical Prague gable-roofed houses, and added an American-style bar and restaurant with spectacular views of the river and the city, loosely modelled after San Francisco’s Cliff House.2

The other son, Miloš, was also inspired by California, though more by its dream entrepreneurs than by its developers. On the vacant land next to his brother’s property development, he built one of the largest film studios on the continent, becoming one of the founders of the Czech film industry. The semblance to the Hollywood Hills was so striking that one half-expected there to be a big sign perched up on the hill for everybody to see from near and far. And indeed, there has been a five-metre-long steel memorial plaque with the name ‘Barrande’, the French palaeontologist after whom the rock is named, visible from across the river since 1884, preceding the Hollywood sign by forty years and raising questions about the original inspiration.

The brothers were close, but markedly different. Václav Maria was a serious, no-nonsense, solid family man, a paragon of bourgeois virtues, including a mistress or two kept discreetly out of sight. In his business dealings he was motivated not so much by the ‘capitalist longing for profit … but enterprise, pure and simple – the will to create something’.3 He was a pillar of society, a Rotarian, Freemason and member of assorted other clubs and associations, an enlightened patriot, who brought up his sons in ‘the intellectual atmosphere of Masarykian humanism’,4 politically connected though not politically active, a cultured man, friend to important Czech writers and journalists, with a sizeable library of his own, a good husband to his wife and a ‘wonderful, kind’5 father to his two sons. He was also a genuinely decent and modest man, as is evident from the way he treated his subordinates, and even more from the quiet and dignified manner in which he coped with adversity and social exclusion during the last thirty years of his life.

Miloš the movie mogul was the bohemian in the family, a gay man of lavish lifestyle and popular parties, who preferred the company of film stars and musicians to that of bankers and politicians. He and his circle amounted to what counted for glamour in Czechoslovakia in the 1930s. By most accounts he was fiercely devoted to his studios and loyal to his stars, which led to his involvement in some questionable projects and some even more questionable concessions and compromises following the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, when the studios were turned into part of their war propaganda machine.

Václav’s mother Božena was no mere footnote to this family of strong individuals, but very much a personality in her own right, an archetypal Prague matron, just as her husband was the archetypal gentleman and her brother-in-law the archetypal bon vivant. She organized family life, saw, with the help of several nannies, to her sons’ upbringing and education, remained in charge of the social diary, and dabbled in music, the arts and science. Her father, Hugo Vavrečka, another remarkable product of the national renaissance, was a Silesian engineer, journalist, author and diplomat, an early visionary of Central European integration and, briefly, a minister in the Czechoslovak government.

Though she was by all accounts a good and conscientious mother, and though she encouraged all kinds of intellectual interests in her sons, from chemistry and science in general to literary pursuits and home puppet theatre shows, Božena was apparently not much of an emotionally nourishing parent, especially with respect to her first-born. She doted on the younger son, Ivan, born two years after Václav, made Václav responsible for his well-being and blamed him for things gone wrong – not an unusual ordeal for an older sibling.6

On the whole, though, it was a privileged, comfortable and happy childhood, and Václav was a privileged, comfortable and happy child. The only problem, for a child born in 1936, was that it would not last for long.

His mother, a keen documentarian, provided perhaps the best illustration of the contradictions that were to shape Havel’s life. The Family Album of 1938, which she lovingly collected and illustrated with her own drawings, starts with a panoramic photograph of the Barrandov Terraces headlined ‘Venóškovo’ (Little Václav’s),7 with the clear, though mistaken, implication that these would one day be his.

In scores of photographs, many with his mother, father, family, their friends and brother Ivan, against the backdrop of toys, villas and luxury cars, Havel is the very model of a child who wants for nothing. He stands smiling self-confidently, dressed and nourished like a prince. His shyness and insecurity must have developed somewhat later. One of the earliest photographs of the younger brother, a few days after his birth, shows Václav prodding Ivan’s nose with his finger, ‘to verify that I really existed’.8 At the age of four, he was not a little opinionated. Of a bald-headed friend of the family, one Dr Wahl, he enquired why he had no hair. When the man, in an attempt to humour the child, answered that this was because his hair grew outside in, the boy remarked helpfully: ‘And do you know, uncle, that it’s already growing out of your nose?’9

And yet there is a darker note, which Božena did not fail to document in the album. Several of its pages are devoted to disasters, billed without differentiation as ‘Scarlatina’, ‘Mobilization’ and ‘War’. A week before Václav’s second birthday, Czechoslovakia mobilized its army to defend itself against Hitler’s threats, only to capitulate before the ‘peace-saving’ agreement negotiated by Hitler, Mussolini, Daladier and Chamberlain in Munich. Under the agreement, Czechoslovakia lost the Sudetenland with its largely German population, in exchange for guarantees of the territorial integrity of the rest of the country. Five months later, the Wehrmacht occupied Prague, and Hitler imposed a ‘protectorate’ on Bohemia and Moravia, while Slovakia declared an independent state closely affiliated with Nazi Germany. Eleven months later, World War II started, bringing about a tsunami that destroyed large parts of Europe, changed its political map beyond recognition and shattered the well-being and the certainties of millions of families, including Havel’s own.

In the Havels’ case the impending implosion came with a delayed fuse. In 1942, while Uncle Miloš footed a fine line with the Germans in an effort to save his beloved studios, his brother, never a flamboyant type, withdrew from public and social life and moved his family to the relative safety and comfort of Havlov, the family retreat in the rolling hills of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands. There, the boys, catered to by a cook, a maid and a nanny, under the watchful eye of Božena, continued to have an idyllic childhood, not unlike Proust’s Combray, surrounded by whispering pines, the calls of a cuckoo and the smells of Božena’s tempera paints. Even the water from the well smelled sweet.10 Indeed, from the family letters and the children’s drawings, it is hard to discern that a war was on. The major events reported by Božena and the boys during the war and the early post-war period consist of skiing at Barrandov in the winter of 1941, little Václav coming down with scarlatina while visiting his Vavrečka grandparents in Zlín, being chased by geese in the village next to Havlov, or being felled by a ‘cold as big as an elephant’, together with an appropriate drawing of the event, elephant and all.11 Some of the incidents described in Václav’s correspondence to his grandma and grandpa were serious only from the perspective of a ten-year-old: ‘In the afternoon I had to write my penalty homework because we had behaved indecently on an outing. We went to the woods to collect branches and went every which way so that the teacher could not find us.’12 Even at this age Havel went in for dramatic effect: ‘We went to the movies today. The film was called Taboo. It was quite nice, but one old man spoiled it all. He was quite old, ugly and liked young girls.’13 A major event, referred to no fewer than three times in as many letters, was Rezi (the cook), Mařenka (the maid) and Miss (the nanny) going to a ball. Havel notes that they must have enjoyed the dance, as they came back at four in the morning. Mother Božena did not sleep all night.14

The confident Václav and the sweet curly-haired Ivan, addressed by his mother endearingly as Ivánek or even – in her own coinage – as Iveček, continued to stay unaffected by the turmoil around them. In the summer the family is seen dining al fresco at Havlov. When the boys returned with an empty basket from a mushroom-picking expedition, mummy came to their rescue by painting a small pile of appetizing ceps into the photograph. In Zlín, Václav spent a lot of time playing with the family dog, marking the start of a lifelong affection for canines. In the summer the boys swam in the lake nearby, and in winter, when it froze over, they skated there. Apparently, Václav felt physically superior to his little brother: ‘After half an hour I skated like a devil. Ivan kept falling a lot.’15

Encouraged by his talented mother, Václav spent a lot of time on drawings and paintings. His choice of topics could be thought of as symptomatic, even though hardly atypical for a boy of his age. He drew a lot of kings and queens, castles and crowns; he even painted ‘the order of St Wenceslas’,16 apparently blissfully unaware that at the time a distinction of that name was being awarded to Nazi collaborators. He enjoyed drawing soldiers in historic costumes, most of them with Havel-like moustaches or other facial hair. His drawings of birds and mushrooms are colourful and stylized, not unlike what Audubon would have drawn at the age of ten. Ivan, on the other hand, had shown a closer touch with reality, attempting to draw the likeness of Adolf Hitler.

Both boys were fascinated with instruments, complex machinery and factories. ‘Grandpa, could you draw for me how the vacuum cleaner is made up so that electricity goes inside and so that it sucks the dust and rubbish? I can’t wait.’17 Grandpa Vavrečka readily obliged. But intellectual curiosity apparently blended in young Václav with a good deal of empathy and social conscience as well. When asked the temperature one day, he replied puzzlingly: ‘Sixteen on the Réaumur scale,’ and then added: ‘I felt sorry for the poor man. Everybody prefers Celsius, so I took pity on Réaumur.’18

In Havlov during the war, the two boys started attending the village school. Though nothing is known about its standards, on at least two occasions Václav boasted to his grandparents of having straight As on his report card, not failing to add that Ivan got a B in his singing and handwriting.19

The picture we get is of a bright, talented, self-confident and more than a little sapient child. When his grandma was coming for a visit from Zlín, his mother wrote to the older woman: ‘I am sure he will want to read political editorials to you, no doubt adding his own commentary.’20 Havel was a zoon politikon from the start.

For all the enviable aspects of his situation, Havel himself did not remember his childhood as particularly happy. He attributed it to the ‘social barriers’ he experienced as a privileged child growing up in a rural – and largely peasant and proletarian – environment. He perceived this as an ‘invisible wall’, behind which he, rather than his neighbours, felt ‘alone, inferior, lost, ridiculed’ and ‘humbled by my “higher” status’.21

This feeling of being outcast and isolated, and at the same time unfairly privileged, remained with Havel throughout his life. In his own thinking it endowed him with a lifelong perspective from ‘below’ or from the ‘outside’.22 He attributed his problems, which he could not then have diagnosed as existential, to his parents’ ‘unwittingly handicapping care’.23

Unlike Franz Kafka, one of his great models, Havel never felt himself to be a victim of crushing, impersonal forces beyond his control. Maybe it was his inner stubbornness and courage that made him, time and again, challenge and struggle with such forces as an equal, and occasionally as a victor and conqueror, despite, or perhaps because of, the awareness of his own frailty as an individual. It was this rebellious spirit that predestined him for the role of an outcast rather than a victim. His perspective had always been from the ‘outside’ rather than from ‘below’.

Even so, Havel may have been overestimating the uniqueness of his own feelings. It is natural for most adolescent children to experience a sense of isolation from their peers, their families and their social situation. He himself cites the fact of being a ‘well-fed piglet’ as one of the circumstances that added to his sense of being outcast, not quite a unique predicament at that age.

But that is hardly the whole picture. In all of Havel’s reminiscences, testimonies and interviews about his childhood, there is a gaping hole. One does not have to be a psychologist to notice that Havel’s mother, unlike his father, uncle, brother and grandfathers, is rarely mentioned. This is even stranger for the fact that, taking after her father, she was of a more artistic and intellectual bent than her husband, spoke several languages and tried her hand at painting. She also believed in a hands-on approach in raising her children. Although there was a gouvernante in the family, Božena Havlová took it on herself to teach her sons the alphabet, and even designed the big characters that she pinned on the wall.24 She encouraged Václav’s artistic talent as well as his interest in science. Yet Havel rarely mentions her, and most of what we know about her comes from his brother Ivan.

The contrast between Havel’s relationships to his mother and father is well illustrated by two later items of correspondence, both sent from Václav’s boarding school in 1948, as the Communists were taking over the country. To his mother, on 31 May: ‘Did not I forget my fountain pen? What were the election results in Prague and in the country? Otherwise, everything is fine. Respectfully, V Havel.’25 To his father, around 28 September, the St Wenceslas Day: ‘Dear Daddy, let me wish you on your name-day all the best that the heart can wish and words cannot express, mainly that your future name-days occur under better circumstances. Your son Václav Havel.’26

It is one thing to establish that Havel’s relationship to his mother was not particularly close, it is quite another to guess at the reasons why. At first sight there seems to be nothing amiss. Božena was rather typical of well-to-do Prague ladies of her time. She was the czar in her own household, she supervised the education of her children, she entertained and was entertained in turn along with her husband, and she tolerated her husband’s infidelities. Theirs was a good, stable marriage, although it was Václav’s second, and she was sixteen years his junior. She seemed to be both protective and supportive of her sons, and keen on their success.

But somewhere along the way, she apparently contributed to the deep ambivalence towards the opposite sex that characterized her older son throughout his life. There was the deep-seated need for female company and its tenderness and comfort, but also for the guidance and order it could provide. For all his life, Havel instinctively sought the company of strong, dominant, directive women who could assuage his sense of helplessness and insecurity. At the risk of using a tired psychoanalytical cliché, they all, in one way or another, resembled his mother.

At the same time, Havel often disrespected and persisted in running away from the very authority and order that the women in his life provided. Though thinking about the intricacies of the relationship between a man and a woman occupied a lot of his time and informed much of his writing, he spent most of his time in the company of men, where he was more often than not the dominant figure. Although he attached much importance to the sharper instincts of women and their better ability to communicate with the deeper mysteries of life, he had little respect – with a few notable exceptions – for their intellectual abilities. In Letters to Olga, he would exhibit a somewhat patronizing attitude to his wife’s writing and thinking.

This conflicting attitude towards women is also clearly reflected in Havel’s presidency. On the one hand, he kept surrounding himself with women, and at one time had even risked comparisons with Muammar Gaddafi by having two female bodyguards in his close security detail. At the same time, he would not often entrust a woman with a position of high responsibility. From among more than a hundred ministers he appointed to the government during his time as president, fewer than five were women. The two women in the erstwhile inner circle of the presidency, Eda Kriseová, an old friend and a fine short-story writer, and Věra Čáslavská, the seven-time gold medal-winning Olympic gymnast, were assigned to deal with the letters to the president and to advise on social and welfare policies, respectively. In the subsequent period of his Czech presidency, Havel relegated women to the roles of assistants and secretaries. The only professional women of importance on his team were then his legal counsels, both private and official, and Anna Freimanová, in charge of his literary rights. Ultimately, perhaps, he preferred to rely on women to protect his personal well-being and interests.

Anyone with an ambition to provide a nuanced picture of Havel’s personality will thus have to deal with the deep duality traceable all the way back to his early years and not limited to his relationships with women. Combined with the awkwardness of a chubby self-conscious child, there emerged from the earliest age the assured self-confidence of a precocious boy with unending curiosity and intellectual interests well beyond his age. Through all the ups and downs of the roller-coaster life that lay ahead of him, both sides of his character remained clearly in evidence. If anything, his self-confidence increased in direct proportion to the adversity and difficulties he faced, and his doubts came to be inseparable from the moments of his greatest achievements. Such a mental disposition does not inevitably make for an easy life, but it can make its bearer well equipped for dealing with its complexities.

1

Václav in Czech.

2

In April 1969, Václav’s brother Ivan, then on a doctoral fellowship at Berkeley, sent his father a postcard of Cliff House and the surrounding Seal Rocks. ‘The sea lions are real. I saw them, barking.’ In the margin, he adds: ‘Inside it resembles Barrandov even more.’ Ivan M. Havel’s archive, Václav Havel Library (hereafter VHL) ID18301.

3

Disturbing the Peace (1990), 4.

4

Ibid. 7.

5

Ibid. 5.

6

Conversation with Ivan M. Havel, Košík Farm, 20 August 2012.

7

Like many frequently used names, ‘Václav’ in Czech lends itself to a dozen colloquial and diminutive forms, signalling various degrees of familiarity and affection, like ‘Véna, Venca, Venda, Venoušek, Vašek, Vašík, Vašíček’, etc., most of them applied to Havel by other people during his life. Interestingly, by dropping the ‘u’ in ‘Venóškovo’ Božena signals here her Silesian extraction.

8

Conversation with Ivan Havel, 20 August 2012.

9