0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Enhanced Media Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

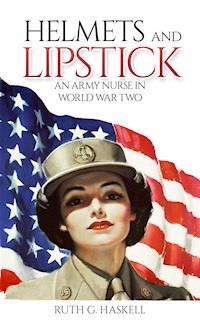

Helmets and Lipstick is the first-hand account of Second Lieutenant Ruth Haskell, chronicling her time spent as a combat nurse with U.S. troops in North Africa during Operation Torch. First published at the height of the war in 1944, Haskell’s memoir is a classic account of combat nursing in World War 2, an important addition to the literature of the war in North Africa and of the history of non-combatants in the Second World War.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

HELMETS AND LIPSTICK

An Army Nurse in World War Two

By Ruth G. Haskell

Table of Contents

Title Page

Helmets and Lipstick

Preface

CHAPTER ONE | Orders for Foreign Service

CHAPTER TWO | We Go for a Boat Ride

CHAPTER THREE | An Introduction to Another Land

CHAPTER FOUR | Life in an English Military Reservation

CHAPTER FIVE | Life on an English Transport

CHAPTER SIX | We Reach Our Destination at Last

CHAPTER SEVEN | Under Fire

CHAPTER EIGHT | Holiday Season in a Strange Country

CHAPTER NINE | On the Move Once Again

CHAPTER TEN | To Tébessa in Truck Convoy

CHAPTER ELEVEN | Life in a Field Hospital

CHAPTER TWELVE | We Make a Strategic Withdrawal

Further Reading: Strategy Six Pack 13 – The Caesars, Patrick Henry, My Sixty Years on the Plains, Anne Hutchinson, A Princess from Zanzibar and Journal of a Trapper: Nine Years in the Rocky Mountains (Illustrated)

Helmets and Lipstick - An Army Nurse in World War Two by Ruth G. Haskell. First published in 1944, this book is in the public domain. This edition published 2017 by Enhanced Media. All rights reserved.

––––––––

ISBN: 978-1-387-12749-8.

To MY SON

Preface

––––––––

USUALLY WHEN ONE thinks of the Army in times such as these, a picture comes to mind of a stalwart group of fighting soldiers striding off to war. It is very true that Uncle Sam has many, many nephews in his service, but in these past three years he has also acquired many nieces. Included among the latter are the Army nurses. These are the girls who are striving to take the best care possible of your sons, husbands, and sweethearts. Our need for many more of these girls is urgent, and this book is intended to tell a bit about the trials and tribulations, the fun and the thrills, to be experienced as a member of the Corps. I personally wouldn't have missed the experience for anything I know of, and I am sure there are others who will feel the same way when this conflict is over and we are a nation at peace again.

––––––––

RUTH G. HASKELL,

2nd Lieut. A.N.C.

CHAPTER ONE

Orders for Foreign Service

––––––––

IT ALL BEGAN with a telephone call. The sharp whir of the bell broke the silence of the hot Tennessee afternoon. I lazily reached for the receiver, still checking the chart on which I was working.

"A-15, Lieutenant Haskell speaking."

"Lieutenant Haskell, this is it! You are relieved of duty as of now. Come to the office for your clearance papers. Clear the post. You are to be in New York not later than midnight on Monday." This was the crisp voice of First Lieutenant Marion Harvey, assistant to the chief nurse.

"Yes, ma’am," I answered meekly, placed the receiver carefully in its cradle, and sat there in a complete daze.

Foreign service! I had volunteered about a month before, but now that the orders were actually here, I found I was a little panicky about the whole thing. It was a thing we all talked about but thought of as being in the dim, dark future. I hastily finished what I was doing, said goodbye to my patients, not without some regrets, and dashed madly across the ramp to the nurses' quarters.

Anyone who has ever lived in the Deep South will know what I mean when I say my room was like an oven. I remember thinking it couldn't be much worse out of doors, so I decided to clear the post first. I ran a comb through my hair, dusted a little powder on my nose, and reported to the Chief Nurse's office.

As I entered the office, Kate Rodgers, the camp glamour girl, was going in just ahead of me.

"Where are my clearance papers?" she asked of Lieutenant Moat.

"Are you going, too?" I asked in a rather astonished manner.

"Before I change my mind, I hope," she replied. "This seemed a rather good idea a few weeks ago, but now I don't know!"

I could appreciate what she meant, because secretly I was feeling the same way.

Lieutenant Moat handed each of us a sheaf of papers and explained what they were for. It seemed we had to be signed off the post by all the various departments to vouch for the fact we didn't owe the government any money.

"Am I late?" This was the voice of Margaret Hart of Bristol, Tennessee. "Thought I never would get off duty. We certainly have been having a busy day in the O.K."

Marjie, as we called her, was a contradiction if ever I saw one. Vivacious, good-looking, and a beautiful dancer, always in the throes of either falling in or out of love, she was a marvelously efficient operating-room nurse. This fact had never ceased to amaze everyone who knew her.

Just as we turned to leave the office, Lieutenant Moat asked, "Do any of you know anything about Mildred Harris? She signed for this thing too and she is on leave. I'm not sure where I can reach her."

We all grinned at each other, thinking about what Millie's reaction would be if she found her, because she had been trying for some time to get home on leave.

Just about the time Marjie started to answer her, in dashed Eleanor Faulk. She, too, it seems, was looking for her clearance papers. Lieutenant Moat repeated her question regarding Mildred; Eleanor thought for a second, and then: "Oh, yes, she is visiting with relatives in Rome, Georgia. But I don't know just where."

At this point I began to wonder if I might just possibly be going to be the only Northerner in an entire "Rebel" group.

"How many of us are leaving?" I asked.

"Let me see," looking back at the list before her. "There are five of you. Mildred Harris, Eleanor Faulk, Kate Rodgers, Margaret Hart, and yourself." She began to smile as she told me this, as though she might be thinking the same thing.

The four of us started back for the barracks, and as we walked along we discussed the problem of Lieutenant Moat finding Millie in time to get her started off with us as it was mid-afternoon on Saturday and time was short.

"Listen here," said Eleanor. "I don't see any sense in all of us running around in this heat. Why don't two of us take these confounded papers around and get them signed?"

Rodgers and Hart looked quickly at each other and smiled and I thought: They certainly have something up their sleeves.

Kate spoke up. "I certainly would appreciate it if I didn't have to go. I have a date for the officers' club tonight."

"So have I," chimed in Marjie.

I looked at Eleanor to see what she was going to add, but she looked rather preoccupied and wasn't paying any attention to what was being said.

"I'll take them if someone will come with me. I'm not sure where all these places are. Where is the Signal Corps headquarters, and why do they have to sign us out?"

I couldn't see any sense in going there or to the camp bakery, but it seemed that the Army thought we should, so we didn't have anything to say about it, I guess.

Finally Eleanor and I sadly started off in the heat to get the darned things signed. It was Saturday, and about a third of the people we had to see weren't in. Time was going, and we still had all our packing to do. We returned to the barracks and, much to our disgust, found Kate and Marjie all freshened up, manicured, shampooed, and rested.

"Are you packed?" I asked.

"Yes, Madge packed for us. We're all set. Isn't that fine?"

I muttered something about some people having all the luck and stalked off toward my own room. About the time I arrived there, Pauline Loignon, a girl from home, came in, and the look on her face was something to behold. She and I had come into the Army the same day and had become fast friends. Evidently she had just heard that I had received my orders, and she was much upset about it.

"What am I going to do without you?" she asked. "You know how much I depend on you. I don't want you to go, do you hear?"

"Pauline, honey, in two weeks’ time you'll never know I existed. Stop your fussing and start helping me pack!"

We finally got busy and I began to see my way clear to being able to get to bed some time before midnight. I still wonder who in the world besides myself could possibly have acquired all the junk I seemed to have collected from somewhere. The worst of it was, I didn't want to dispose of any of it. I swear I would have packed the dusty old corsages I took down off the wall if Pauline hadn't thrown them into the wastebasket first.

Late that night as I tried to get ready to sleep, and goodness knows by that time I was ready to, I began to think of all the friends I had made in the past fourteen months and of how much I was going to miss them. Camp Forrest, Tullahoma, Tennessee. I grinned to myself in the dark when I remembered how I had hunted frantically on the map for the place when I first received my orders to report there. That is one sad thing about army friendships, you meet so many people, learn to like them, and then away one or the other goes and you never see them again.

Sunday morning! When I first wakened I couldn't imagine what my trunk was doing there in the middle of the room and packed to overflowing. Then I remembered, this was the day! I lay there a few seconds blinking into the sunlight and wondered what the next month, or even the next week, might bring. I began to wonder about the other four girls and whether or not we would get along. Kate was from Houston, Texas. Slim, pretty, almost Spanish-looking with her black hair and shining dark eyes. She was exceedingly popular with the officers on the post, danced beautifully, and was much in demand socially. She had the knack of getting things done for her rather than doing them for herself, just from the pure force of her personality. As it developed, she had Madge, our colored maid, do her packing for her while the rest of us slaved away at our own.

Marjie was tall, a striking brunette, extremely well proportioned. She appeared to be rather young and not entirely sure of her own mind, although, as I have said before, she was a very good nurse. Her chief hobby in life seemed to be the number of scalps she could collect from the poor helpless males. Her home was in Bristol, Tennessee, and she certainly was the typical Southern belle.

Mildred was a slim little thing, determined and emphatic about her likes and dislikes, and with a temper that flew off at a tangent at the most unexpected times and places. She was a loyal friend if she liked you, and made no bones of letting you know it if she didn't. As I thought of her, I wondered if Lieutenant Moat had been able to reach her, and I smiled to myself as I imagined what she would say if called back from her leave. Her home was somewhere in Georgia, and I often wondered what sort of place it might be.

Eleanor was a type all her own. Her hair was dark brown and reached her waist. She wore it braided and wound around her head coronet fashion. Her nose and cheeks were sprinkled liberally with freckles, which she disliked very much but which served to make her very attractive. She had a rather driving, dynamic personality, evidently used to getting her own way. There were many times when one could shake her for being so very sure of herself, but the damning part of it was that she was almost always right! Her home was in Memphis, Tennessee, and I think, all in all, she was the most likable girl of the gang. "Well, lazybones! Are you going to sleep all morning?" I got up on my elbow to see who was speaking, and there stood Marianna Smith with a tray. It seemed they were to make a lady of me my last day and give me breakfast in bed!

"Get out of there and enjoy this while it's hot," she said as she plopped herself down on the foot of my bed.

"You know, don't you, that you are going to be missed around here?" She looked rather serious for a second, and then: "In a way I wish I were going, too, but I guess I can't just make up my mind what I want to do and when!"

"I rather think I'm going to be lonely for all my Camp Forrest friends, too. You know, folks have been darned nice to me around here."

Some way or other I managed to finish all the last minute things one has to do when packing. I looked around the little boxlike room that had been my home for the past fourteen months and wondered what the future would bring. If I had only known!

"Ruth, you are wanted on the telephone. You are going to have dinner with us in the mess hall today, aren't you?" asked Pauline.

"Yes, honey, I sure am. I’m glad it's fried chicken. Lord only knows when I'm apt to get another one." I walked over to the telephone. "Lieutenant Haskell speaking," I said.

"Lieutenant Haskell, this is the Chief Nurse. There will be transportation for you girls to go to the station at two-forty-five. Be at Quarters One at that time. Your reservations are all made, and your luggage will be picked up shortly after lunch."

I thanked her, and as I hung up the receiver I had a very funny feeling about this really being terribly final as far as my life at Camp Forrest was concerned.

Two-forty-five, and a station wagon rolled up to the door of Quarters One. I think in a way we were all relieved, because we were a little upset, emotionally, at the many goodbyes to be said.

We were all rather proud of the way we looked. We were wearing, for the first time that summer, the beige uniform of the Army Nurse Corps, and feeling for the first time as though we might really be part of the Army. Up to that time, uniforms had not been compulsory and we wore civies when off duty.

Lieutenant Moat had given Eleanor instructions for the entire group and last-minute orders to remember that we were part of the Army and that we must always be a credit to the uniform.

"I’ll say goodbye to you here as I feel you should start out on this responsible trip entirely on your own. Good luck to you. Keep well. I know I shall always be proud of you, wherever you may be!" With this remark Lieutenant Moat shook our hands, gave us a hurried pat on the shoulder, and left.

"Come on, you kids, we'll be late, you haven't got all day!" This from Ruth Jones, a very attractive girl from Philadelphia who had been a close friend of mine for many months.

"I'll see you at the station," sang out Kathryn Goodman.

Finally we climbed into the station wagon, and as we drove around the circle in front of headquarters I wondered if we would ever be back there again.

"What about our foot lockers?" asked Eleanor of the driver.

"Everything that I own is in it and I’m darned sure I don t want to lose track of mine, do you?" This was little Millie speaking (yes, Lieutenant Moat had reached her, and Rome, Georgia, was not too far away).

"They are all at the station and are to be shipped through on your tickets. Don't worry about them. They will be there when you arrive." Thus spoke the driver of the vehicle as we drove up into the yard of the station.

It being hot enough almost to cook a gal, I for one was glad when we saw the locomotive of the good old Chattanooga Choo-Choo rounding the bend. Everybody who had come to see us off kissed us goodbye (even a few soldiers who were just innocent bystanders! Guess they thought it was like a wedding, where everybody kissed the bride!).

"Write to me soon. I hate to write letters, but I promise I’ll answer every one I receive." Jonesy looked a little bright around the eyes as she said this.

I laughed and hugged her close to me.

"See you in Timbuctoo or some other fine place. You will be following us soon."

(You can imagine my surprise when I came face to face with her in Algeria some five months later!)

We pulled slowly out of the small town of Tullahoma, and as we looked back at the barracks of camp fading from sight, we all became very quiet. Guess we realized how many good friends we were leaving behind, and our minds were crowded with memories of all the fun we had enjoyed there.

Several hours passed. Each of us had apparently been lost in thought about personal problems.

"I'm hungry," Eleanor said. "What do you say we go into the diner for a bite to eat?"

"Fine, I didn't realize I was so hungry. What about the rest of you girls, are you coming with us?" Marjie stepped out into the aisle and started down toward the end of the car.

"Why don't we all go?" I asked, and promptly followed the other two girls.

We enjoyed a fine dinner, for which we paid just about enough to buy the train, and returned to our seats to read for a while before the porter made up our berths.

We arrived in Washington the next morning, and as we came back through the train from having breakfast in the diner, we passed another group of about six girls who were gazing out of the window in a very disconsolate manner. I recognized the Nurse Corps insignia on the collar of one of the girls' shirts.

"Excuse me, but aren't you Army nurses too?" I smiled at one of the girls and hesitated by the seat.

The rest of the girls had gone on ahead, so I sat on the arm of the seat to talk to them for a second. It was a boiling hot day, and I felt badly for them because they were wearing their winter woolens and I was nearly dead in a Palm Beach cloth suit!

"We are from Camp Wheeler, Georgia," volunteered one of the group.

I replied that we were from Camp Forrest down in Tennessee. "I imagine," I added, "you are going to the same place we are."

One of the girls seemed willing to talk and visit, but the others were rather distant. Finally I asked her if she wouldn't like to join us back in the other car, and along she came.

"You know, I didn't ask to come on this safari." She looked a little indignant. "I've only been in the Army a couple months and didn't expect orders for foreign service for some time. Oh, well, I guess it doesn't make much difference as long as I have to go sometime anyway."

This girl was Louise Miller, a winsome little blonde from Selma, Alabama. I instinctively liked her. She was frail and, like myself, of average height with fair complexion.

I was much surprised that she had received orders without volunteering for the mission. She told us that not enough girls had volunteered to go, so their chief nurse had just picked two girls to fill the quota.

Soon she returned to her friends and we began to gather our things together, as we were due into the city in a very short time.

Orders for our group read: Report to the Port of Embarkation. Mildred Harris was the only girl in the group who knew New York at all. I had been there a couple of times with patients and had gone up to the World's Fair the year it opened. But, I certainly didn't feel I knew enough about the city to find my way around—to say nothing of getting the gang of us to the port.

After much discussion we decided to taxi to the Army Base, and so we piled the five of us, luggage and all, into one of the ubiquitous Yellow Cabs and off we started on what was to prove an adventure. In the first place the cab driver was strictly a Manhattan product, and after he got out of the midtown district he didn't know where he was, and neither did we! He seemed much amazed that we knew where we wanted to go but didn't know how to get there. Finally, after riding back and forth and around and about, we arrived at the front gate of the Army Base with an armed guard walking slowly back and forth giving everybody suspicious looks. It seems you are definitely wrong until you prove you have a right to be there. We all had passes of the regular Army type, the kind that has a picture of you pasted on it that looks more like your old maid aunt than it does like you. We finally convinced the guard that we had business there, and he let us through the turnstile. Of course on the way through I practically had the suitcase torn out of my hand. Just a little gal from the country!

We walked into a large barnlike building. Finally we came across another soldier with a gun over his shoulder.

"Say, soldier, where is the Chief Nurse's office around here?"

He grinned in a condescending manner and told us to take the elevator to the third floor and, when we got there, to ask for Lieutenant Witter’s office.

Finally, after following instructions, we arrived in a huge room on one side of which dozens of soldiers and girls sat at typewriters working like mad. A little farther on were about fifty nurses looking as if they had lost their last boyfriend. We finally located the Chief Nurse, and Eleanor passed over the envelope containing our written orders. She looked them over hurriedly and waved us on to where girls in groups of four or five were writing at several small tables.

"I wonder what those girls are doing?" asked Kate.

"I don't know, but I imagine we'll soon find out. Let's go over and ask. Probably we have to do the same thing."

With this remark Eleanor led the way over to the nearest group of girls who were standing around looking as puzzled as we were. It developed that this particular group were from Fort Knox, Kentucky.

"What are all these girls writing?" asked Mildred. "Do we have to do it, too?"

At this point the Chief Nurse came to our assistance.

"All you girls who have just arrived come over to this section of the room and we'll explain how you are to make out your insurance and allotment papers."

About the time we got it through our thick heads what we were to do to the various forms we were given to fill out, another girl came bustlingly over to us and said, "If you are finished, you are to come out back to the dispensary and have your shots."

"Shots! What kind of shots?" we all chorused as one.

"Tetanus, typhus, and typhoid!"

"All at once?" we cried.

"Certainly," she smiled sweetly. "You are in the Army now, or didn't you know?"

With that remark we felt there was very little left to say, so we just followed her—not without some fears, for we had heard many an enlisted man rave about the "assembly line" method of inoculations.

We all stood in line and one by one received our shots. The medical men who were giving them to us were as impersonal as though they were sticking a hypo needle into an orange (as we had been taught to do early in our training days). They looked down our throats, listened to our chests, tapped us here and there, and pronounced us physically fit for whatever was ahead of us.

By this time we were getting pretty tired, but it seemed we had only just begun! We lined up again, this time to receive our issue of field equipment. Holy cats! First we received a sack-like affair that they told us was a musette bag, and then a belt with a container hanging from it that was to be our source of drinking water from there on in. When they passed me some sort of gadget that looked like a frying pan with a cover, they told me that it was my mess kit! That didn't mean a thing, then, but I certainly found out it was a mess in more ways than one before the next ten months were out.

"Have you girls received your bedding rolls?" asked Lieutenant Witter.

We looked a little puzzled. We had no idea what she was talking about.

"I guess you haven't, if I am to judge by the very intelligent look on your faces!" With this remark, she spoke to a soldier who was standing nearby and told him to take us along with him and to see that we received a bedding roll and were taught how to roll it.

First we were given a huge canvas-like affair with three huge straps on it. The soldier spread mine out on the floor, and we discovered that there were two pockets on each end of the thing and that the sides folded over and strapped before it was rolled. I was still in doubt as to what it was when the soldier said,

"Have you anything you want to pack in this?"

"What in heaven's name is it? What do you mean, do we have anything to pack in it?"

He gave me a withering and pitying look, and I began to feel properly squelched.

"This, my dear Lieutenant, is your bed and your trunk all in one. You pack your clothing flat under your blankets, always arranging it so that when you open the thing it is ready to sleep in. The pockets are for your shoes and small equipment, and you must interfold your blankets for warmth. You are a field soldier now."

About two hours later we emerged from that room perspiring and hot and tired, but with more than a vague idea what a bedding roll was and at least some idea how to roll the thing so that it wouldn't fall apart the first time it was picked up from the floor.

At this point I had begun to wonder if we were ever to get anything else to eat, but it seems that was the least of our worries. We were soon herded into one small room to have gas masks issued. August in New York, and we spent the greater part of another hour trying on face pieces of various types of gas masks to see if they fitted. Personally, I didn't see what the difference was between one that didn't fit and one that did, but there was a very stern gentleman wandering about with a birdie on his shoulder who seemed to think that there was a difference. I think we signed for the things and left just before he decided we were a group of mentally incurables.

"Young ladies, step over to this section and sign up for your helmets."

That did it. As we entered that room, a smart-looking corporal planked a helmet down on my already aching head, grinned, and swung me around to the mirror. Ye gods, I knew I wasn't anything to look at, but the face I saw reflected there was enough to scare children.

"That isn't exactly a Knox model, miss, but you will find that it is a comforting sort of thing to have between your head and any stray shells or shrapnel. Besides, it makes a grand washbasin."

When we had signed about a million forms and received enough equipment to take care of a small army, we were told to report back there at six-thirty the following morning. We were told also that our foot lockers would be at the hotel and we should have them completely packed and ready to be picked up early the next day.

Finally we hopped a cab and arrived at the hotel. We must have presented a pretty picture. We entered the lobby with gas masks slung over one shoulder, musette bag over the other, and carrying our suitcases, canteen belts, and helmets. Leave it to a New York hotel clerk to be blasé, for this one didn’t bat an eyelash when we registered.

"Have you foot lockers in the baggage room for Lieutenants Haskell, Faulk, Harris, Hart, and Rodgers?"

The clerk called the baggage room, only to tell us that our lockers were not there as yet. That rather staggered us, as we had traveled in summer uniform, and our wools that we would have to wear on board ship were in our lockers with our overcoats and sweaters.

Marjie and I were assigned to room together and were taken to a room on the sixth floor. We dropped down onto the bed from sheer exhaustion before the bellhop had time to get the door closed.

"Ruth, aren't you terrified at the thought of that ocean trip?" Marjie asked.

"I hadn't thought about an ocean trip," I confessed, "to say nothing of Uncle Sam paying for one for me." I fell to wondering what kind of sailor I'd be.

We went to sleep without bothering to get anything to eat, and all too soon the desk clerk called and told us it was six o'clock. We asked if the lockers had ever been delivered to the hotel, and she informed us that as yet nothing had come for us. We really began to be concerned about it then, and wondered what we would do about the uniform situation.

As soon as we reported back to the Port of Embarkation we told the Chief Nurse that we didn't have our lockers. She looked rather annoyed and said she would have them checked on from the Tennessee end of the trip and see if they had ever been put onto the train.

We spent another two hours getting registered here and there, and then Lieutenant Witter came and told us our lockers had not been put on the train and wouldn't arrive in New York until after we were due to sail. She took us to the storeroom and issued us uniforms and warm clothing for the ocean trip, and we had to put our pretty beige uniforms into the confounded bedding rolls, and I think we were pretty well satisfied we had seen the last of our belongings. I was very unhappy, because I had had my uniform altered to fit and the one I was issued was a forty-two chest measure and I wore a thirty-eight.

About noon we were told that the afternoon was ours to do with as we wished, that we mustn't make any long distance calls to our parents or boyfriends, and that we mustn't send any telegrams that might give out any information as to the troop movement in the offing. We were told to report back by eight the next morning ready to go on board the transport.

That evening our group went out to have a final fling. We went into a restaurant just before returning to the hotel and decided to order what we wanted to eat no matter what it cost. You could almost tell where we were from by what we ordered.

"I’ll have fried chicken," chorused the Rebels.

"Make mine a sea food plate," said I, a stern New Englander.

It didn't work with the dessert course, though, as we all settled eagerly for watermelon.

Back to the hotel and to bed. Tomorrow would be the day, and we were all too excited to sleep.

CHAPTER TWO

We Go for a Boat Ride

––––––––

"COME ON, MARJIE, it’s time to get up. We’ve a date with the Army today, and somehow I don't think we'd better be late." With this remark I swung my pajama-clad legs over the side of the bed and staggered sleepily toward the bathroom. I remember wondering, as I stood there under the needle-like spray, where I would be likely to take my next shower—and when.

"I don't want to get up," protested Marjie, petulantly. "As far as I'm concerned, Haskell, six-thirty only comes in the afternoon."

"But this, my little chickadee," said I from the shower, is the day we go for a boat ride. Remember?" There was a lazy yawn from the bedroom. "Oh, all right. All right. Get out from under that thing so I can get in."

In a short time we joined the rest of the group in the foyer of the hotel. It was terribly hot, and we were dressed in our winter blues with gas masks, canteens, musette bags, and what have you, all over us. Needless to say, we were anything but comfortable. Eventually we checked in at the Army Base and arrived upstairs just in time to receive orders to go back down again and line up for the march to the ferry which was to take us to the transport.

"My head aches," said Kate. "Besides, I don't see any sense in wearing all this collateral right here in New York." With this remark she gave her helmet a shove back on her head, only to have it promptly drop down over the bridge of her nose. Poor Kate. I thought: Well, darling, you may have had Madge do your packing for you, but you sure as blazes are going to have to wear your own helmet.

We stood there in formation, a very unmilitary-looking lot. I don't believe anyone had a very comfortable-fitting uniform, and we were all a bit nervous and apprehensive. That was a very deep and wide-looking ocean out there, from where we stood.

"Well, girls, good luck to you. We have only known you for a few hours but I’m sure you are the sort of girls who will go over there and do the job you have volunteered to do, and do it well. Keep well, and remember you live in the finest nation on this earth. Be a credit to that nation, the uniform that you wear, and most of all to yourselves. May God watch over and keep you, one and all." The Assistant Chief Nurse finished speaking and smiled at us, the sort of smile that just seems to enfold you in its sincerity.

"Attention—forward march." With this order we fell into line and started the long hike which would bring us to the dock.

There was the sound of a long-drawn-out whistle, and we looked up to see a large number of soldiers hanging out of the windows and grinning their heads off. I imagine we did present a funny sight with all that equipment just hanging off us, and most of us out of step, but even at that we didn't quite appreciate being laughed at. Later we learned to whistle right back, but at that time we were exceedingly annoyed.

As we lumbered along toward the harbor under the load of assorted equipment we could look up and see the old Statue of Liberty stood there in all her glory as though she were watching over her children. Soon we bumped and banged against the side of the transport, which appeared to be a rather large affair, and then the trek up the gangplank started. Our luggage had been carried on board for us, but we all felt rather weighed down by what we had on our backs. An officer stopped us and asked us our names, and gave us a stateroom number and told us how to get there.

''What's your stateroom number, Eleanor?" asked Millie.

"Sixty-four on A deck. What's yours?"

"Why, that's my number too," chorused Marjie and Kate together.

Just then I received a card bearing the same number, so it looked as though the Camp Forrest five were to stick together for the time being. After a fashion we reached A deck and Stateroom 64. The transport had evidently been one of our luxury liners before being converted into a troop ship, and the stateroom was a beautiful one with all the niceties removed. It seemed there were to be six of us to a room originally intended for three. There were three regular beds in the room, one of them a second-story bunk, and three regular Army cots, the canvas folding kind.

"This one is mine," announced Eleanor, throwing her luggage on the bed nearest the portholes.

"I want to be next to you," said Millie, and she chose the cot next to Eleanor's bed.

"This one looks all right to me. First come, first served," and I dropped my things down on the other bed. That left two cots and the upper bunk. Soon Marjie and Kate wandered in, and as they were discussing the sleeping arrangements, a slim, rather attractive-looking girl [...]