Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

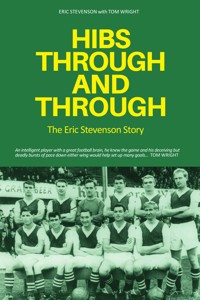

On 21 May this year, Hibs made history by winning the Scottish Cup for the first time since 1902. It was a time of celebration when the supporters revelled in their victory and remembered the great heroes of the club. Eric Stevenson is one of those great heroes. When he was inducted into the Hibs Hall of Fame at Easter Road in 2012, Stevenson declared, 'This means everything to me. My uncle founded the Bonnyrigg Hibs supporters club in 1949–50 and I started going to games when I was seven'. This book traces Stevenson's fanatical interest in the club from a very young age, his time as a left-winger wearing the number eleven green and white jersey in the '60s, and the well-deserved recognition that he has gained today. Throughout his career, Stevenson also played for Hearts and Ayr United, but this story shows that ultimately he is truly Hibs Through and Through.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 535

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TOM WRIGHT was taken to his first game aged nine, a friendly against Leicester City at Easter Road in February 1957. Little did he realise that football, and Hibs in particular, would become such a major influence in his life from that day on. Wright has now been a Hibs supporter for over 50 years, and has the scars to prove it. Previously the Secretary of the Hibs Former Players’ Association, Wright is now the official club historian and curator of the Hibernian Historical Trust. He is the author of Hibernian: From Joe Baker to Turnbull’s Tornadoes, The Golden Years: Hibernian in the Days of the Famous Five and Leith: Glimpses of Times Past and he is co-author of Crops: The Alex Cropley Story.

ERIC STEVENSON comes from a staunch Hibs background – his uncle was a founder member of the Bonnyrigg Hibs Supporters Club. As a schoolboy in 1960 he signed briefly for Hearts, then fulfilled his dream of becoming a Hibs player. Between 1960 and 1971, he made 257 appearances and scored 53 goals. Eric’s intricate close ball control allowed him to regularly outwit the opposition and win a number of penalties. After an eventful career in football, culminating with a spell at Ayr United United 1971–73, he and his wife Agnes ran a successful business in Bonnyrigg for many years. To this day he is a fanatical Hibs supporter.

Hibs Through and Through

The Eric Stevenson Story

ERIC STEVENSON

with

TOM WRIGHT

First published 2016 eBook published 2017

ISBN: 978-1-910745-67-0 eISBN: 978-1-910324-95-0

Eric Stevenson and Tom Wright © 2016

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1:Early Days

2:Signing for the Hibs and Disappointment in Rome1960–61

3:Šekularac, Hugh Shaw’s Resignation and Walter Galbraith1961–62

4:Injury, a Freak Winter and Relegation Dogfight1962–63

5:Exit Harry Swan and Enter the Big Man1963–64

6:The Summer Cup, Real Madrid and Dreams of the ‘Double’1964–65

7:A Stroll at Tynecastle and Semi-Final Disappointment1965–66

8:An Epic Battle at Dunfermline and a North American Tour1966–67

9:See Naples and Die and a Controversial Four Step Ruling1967–68

10:A£100,000Footballer and League Cup Disappointment1968–69

11:Willie McFarlane and a Scottish League Cap1969–70

12:The Ibrox Disaster, Liverpool Fiasco and Dave Ewing1970–71

13:Almost the End1971–72

14:A Dream Team

15:And Finally

Photographs

To my wife Agnes, daughters Sonya and Nadia, and grandchildren Owen, Aidan, Connor, Lucy and Logan.

Acknowledgements

MY THANKS TO Gavin at Luath Press for suggesting a name for the book which in the circumstances was so very appropriate. Most of the photographs in the book are from my own personal collection. The Summer Cup final image is courtesy of the family of the late Peter Caruthers. My thanks also to Tom Purdie for the use of two photographs (Eric playing in the Scottish Juvenile side against at Muirton Park and in his early days at Easter Road). Every effort has been made to locate image copyright holders and to trace sources of media quotes.

Introduction

FOR OVER TEN years Eric Stevenson was probably the best uncapped player in the entire country.

Born at Eastfield near Harthill, Eric comes from a Hibs background, his uncle a founding member of the Bonnyrigg Hibs Supporters Club. Stevenson had been signed by Hearts as a schoolboy, but a contract irregularity later saw the Tynecastle club fined £150 and manager Tommy Walker £75. Hibs, who had been keeping a close watch on the situation, soon stepped in to contract the player to Easter Road. It was a deal that was to pay long term dividends for both parties, Stevenson a lifelong Hibs supporter, realising his life’s ambition to play for the club, Hibs reaping the reward of over ten years’ sterling service from one of the best players ever to wear the famous green and white jersey. Making an almost immediate breakthrough into the first team, barring injuries he would be an almost automatic first choice over the next decade.

During his time at Easter Road Eric would play, with and against, some of the biggest names in the game, taking part in many memorable matches that are still spoken about today, including games against Napoli, Liverpool and Leeds in European competition and many other unforgettable domestic fixtures and a League Cup final.

Equally capable on either wing, he was usually to be found wearing the number 11 jersey, his mesmerising close ball control consistently bemusing the opposing defenders. An intelligent player with a great football brain, he knew the game and his deceiving, but deadly bursts of pace down either wing would help set up many goals for the likes of Joe Baker, Neil Martin, Jim Scott, Colin Stein and later Joe McBride. He also had an eye for goal himself, as he showed when scoring two of Hibs goals in a 4-0 defeat of Hearts at Tynecastle in 1965, when all four were scored in the opening ten minutes of the game.

Slightly built, his intricate close ball control would also help him win a number of penalties for his side. Eric insists that he never dived, although he did not try too hard to stay on his feet.

During his time at Easter Road he would play under a succession of managers from Hugh Shaw to the irrepressible Eddie Turnbull. Much admired by the latter who had earlier tried to sign the player for Aberdeen. Unfortunately personal difficulties meant a move to Ayr United shortly after Turnbull’s return to Easter Road as manager in 1971.

Although retiring prematurely at the age of almost 31 to concentrate on his business interests, a time when he should have been approaching his best, Eric is still fondly remembered by those who saw him play and remains a great favourite of all the Hibs fans who were fortunate enough to have witnessed him at his very best. He left the game with only a single appearance for the Scottish Inter-League side, scant reward for his undisputed talents.

He remains to this day a fanatical Hibs supporter. This was never better demonstrated than when he was fined two weeks’ wages by the then Ayr United manager, Ally MacLeod, for missing a game one Saturday. Where was Eric that day? At Hampden, watching Hibs beat Celtic in the League Cup Final. That, says Eric, was money well spent.

A member of the Hibernian Former Players Association, in 2012 the popular Eric Stevenson was inducted into the Hibernian Hall of Fame and still attends games at Easter Road today.

Tom Wright

CHAPTER ONE

Early Days

I WAS BORN on Christmas Day 1942 in the small coal mining village of Eastfield, near Harthill in North Lanarkshire. At that time the Second World War had well over two years to run, but with the industrial towns and cities like Glasgow and Clydebank not all that far away, a sleepy village like Eastfield didn’t seem to be of much interest to Adolf Hitler and his German bombers. Eastfield was just one of the numerous small towns and villages in the area that depended almost entirely on the pits for its very existence, an industry that for centuries had proved so vital to the country’s economy. Coal had been mined in Scotland for hundreds of years, but it was the coming of steam in the late 18th century that created an almost insatiable demand for the fuel. More and more mines started to spring up, employing, particularly in the mid-1800s, men, women and even children as young as five, many of them Irish immigrants who had fled to Scotland to escape the great potato famines that were ravaging Ireland. It was dirty and dangerous work with many serious accidents, often with fatal consequences. Scotland’s worst ever mining disaster occurred at nearby Blantyre in 1877 when 209 men and boys lost their lives. By the beginning of the 19th century, in Lanarkshire alone there were 200 pits, the industry reaching its zenith just prior to the Great War. By 1947 and nationalisation, there were just 190 mines of varying sizes in the whole of Scotland. By the 1980s only five remained, the closing of the pits forcing a great number of decent hard working miners to look elsewhere for employment.

My mother Christina, or Teen as the family knew her, came from mining stock, her father spending his entire working life at the pit. At the beginning of the war Teen had become engaged to a lad called Alistair, who also lived in the village and worked at the mine. Alistair would eventually be called up for military service and posted overseas. These were difficult times, the population uncertain of just what the future had in store, and unfortunately Teen found herself in the family way, as it was quaintly described at that time, me being the result.

There was obviously no way that Teen’s condition could be kept a secret for long in a small village like Eastfield, but to be fair to Alistair who was always very good to me when I was growing up, on his return from the forces he agreed to stand by my mother. Perhaps understandably though he struggled to come to terms with another man’s child and I was sent to live with my gran and grandad Cove, who also lived in the village.

I have very few memories of Eastfield in the early days, although I can still vividly remember coming home from school one day to be told that my gran had died. I was still very young and obviously there was no way that my grandad could manage to look after a young child on his own so once again I was on the move, this time to live with my mother’s sister Nan and her husband Tam Clark, who for some unknown reason was called Elk by his friends. Like countless other, Tam had spent his entire working life at the pit, but with several of the mines now on the verge of closure he and many of the other men from the surrounding areas were forced to look elsewhere for work.

It must have been around 1948 or 1949 that uncle Tam and several other men from the village went looking for fresh employment, either at the then modernised Lady Victoria pit at Newtongrange or at Bilston Glen. In our case it meant moving into a corporation house in Bonnyrigg which was only a few miles from Edinburgh. Nan and Tam already had a family of their own in Henry who was four years older than me, but I quickly settled in to my new surroundings and to be fair to them I was treated no differently to Henry whom I had taken a liking to immediately. Some time later two half-sisters Christine and Mary would arrive on the scene.

I remember that Tam was always full of encouragement for us youngsters. Once during the local Poltonhall Gala I was leading in a race when I was pushed from behind by another boy, causing me to stumble, so could only manage to finish in second place. The other boy was declared the winner, but my uncle wasn’t having any of that. He stormed over to the judges’ table claiming that clearly I had been pushed and that the decision should be reversed and he got his way. That was the kind of guy Tam was, always full of support.

We lived in a four-in-a-block upstairs-downstairs house in Pryde Avenue which I imagine would have been a far cry from a miner’s house in Eastfield. This house actually had its own bath, a world away from the customary large tin tub in front of the fire that the miners had been accustomed to.

I managed to settle into my new surroundings immediately, attending the local primary school, and have nothing but happy memories from early childhood. For a youngster, life in my new environment was idyllic, our out of school hours usually spent playing football either in the local park or in the street with my pal Daniel Hughes. In those relatively care free days it was normally the latter, and only rarely would our games be disturbed by a passing vehicle of any sort, usually only the coal lorry or the very occasional visitor to the area who actually owned a car.

I was aware from the very beginning that Tam and Nan were not my real parents, something that didn’t bother me in the slightest, but there could be the occasional confusion over my surname. One day at school the teacher asked an Eric Clark to stand up, and it was only when I was nudged by a classmate that I realised, much to my embarrassment, that the teacher was actually addressing me. Other than that I really enjoyed my time at school. One of my last acts at the primary school was to play the part of a page boy complete with wig, tights, the whole caboodle, in the Coronation celebrations in 1953. God knows what my pals must have thought of me. Although I was no scholar I couldn’t have been all that thick, as the pupils involved in the pageant were usually selected on their academic ability.

Another vivid memory I have from school is watching, either in the cinema or on a neighbour’s television, as we didn’t own one ourselves till much later, Hungary defeating England 6–3 at Wembley, particularly the famous Puskás goal when he drew the ball back with sole of his boot to leave full-back Alf Ramsey floundering on the ground, before firing a fierce shot past goalkeeper Gil Merrick into the top corner of the net. That evening all us boys were out in the street trying to emulate the move.

It was around then that I was considered old enough to visit my mother on my own, although at that time I still didn’t know that she was my mother. I was only about nine or ten when I was first put on the bus to St Andrew’s Square in Edinburgh. There I would catch the bus to Harthill where I would be met by my grandad, later making the reverse journey home. It sounds a terrible thing now to let a lad that young travel such a distance by himself, but these were more innocent times and nobody ever thought much about it.

At that time Hibs were by far the best team in the country, and one day Big Tam and a few of his pals, who all drank at the Anvil pub in Bonnyrigg High Street, decided to form a local branch of the Hibs Supporters Club. During the immediate post-war years, Hibs were a huge draw and were well capable of attracting crowds of 30 or 40,000, often more, and soon the supporters club was thriving. The bus would leave from the High Street in Bonnyrigg for both the home and away games and would invariably be packed, stopping at nearby Dalkeith to pick up more fans. I don’t know in the early days if the club would have been officially affiliated to the Hibernian Supporters Association that had been formed in 1946, but by 1952 with Tam as chairman and Alex McQuaid as secretary, they had been accepted as full members, one of almost 40 supporters clubs throughout the Lothians and Fife. From what I can remember, monthly meetings were held in the church hall at Poltonhall, the occasional Sunday excursions always eagerly anticipated by the children.

Came the magical day when along with Big Tam, Auntie Nan, Henry and my pal Robert Healy, who has now sadly passed away, I was taken to my first game. I could only have been seven or eight and unfortunately I have no memory of who Hibs were playing that day, or even the score, all I know is that the entire proceedings made a great impression on me, and started a passion for the game that remains as strong today. A passion for Hibs in particular, but also for all things football. In the ’50s the Scottish game was experiencing arguably the greatest period in its history and there was no bigger draw than the Hibs. During the war thousands of young men serving abroad had been deprived of their traditional Saturday afternoon pastime of watching their favourite sides in action, and the game in the immediate post-war years attracted supporters in unprecedented numbers. Nearly everyone worked on a Saturday morning, and with few of the leisure pursuits that are available or acceptable nowadays, like betting shops, TV, or even going shopping with the wife, it was common practice for the men to have a few pints after work in the local pub, then it was off to watch their heroes in action.

After that first game my appetite had been whetted. I wanted more, and soon I was attending games both home and away, with the possible exceptions of Parkhead, Ibrox or Tynecastle (places that my uncle Tam considered to be unsuitable for youngsters of my tender age). My main problem was that I would burst out crying on the rare occasions that Hibs lost. Apparently I was well known for it. The men on the bus would try to cheer me up, but uncle Tam would always insist jokingly that he was not bringing me back. I particularly remember one away trip to Methil to see Hibs play East Fife who were then one of the top teams in the country. On the way Tam bought me a ticket for the customary sweep that was always held on the bus. I remember drawing a player called Eddie Turnbull who fortunately scored the first goal that afternoon to make me a winner. Little did I know then that not only was I to become great friends with Eddie in later years, but would actually line up alongside him in practice matches at Easter Road.

For home games the bus would park in one of the many side streets near the ground and in those more innocent days we would be given the admission money and complete with our autograph books would be allowed to run ahead, hoping to get a lift over the turnstiles from a passing adult which would allow us to keep the money. Once inside the ground we would make our way to the top left-hand corner of the ‘Dunbar End’ where we knew we would find our grownups. It was the perfect spot to watch the Hibs international left winger and future Scotland manager Willie Ormond making his mazy runs up the left wing, little realising that within a few years I would be pounding that same furrow myself.

Willie was a talented outside-left whose direct style of play was perhaps in direct contrast to the exquisite ball skills of Gordon Smith on the other wing, but he was no less effective. Capped half a dozen times for the full Scotland side and nine times for the Scottish League, he helped Hibs win three championships between 1948 and 1952. At that particular time the Famous Five was in full flow, each one a Scottish International in his own right and it was something to see them at their very best as they swept through the opponents defence with consummate ease.

Inside-left Eddie Turnbull, who as I have already mentioned would later become a great friend, was considered to be the workhorse of the side, but he was far more than that. A rugged, but determined competitor with a great engine and thunderous shot, his never-say-die attitude inspired the side on the rare occasions when things were going against them, and it was only later when I played alongside him in training at Easter Road that I realised just how good a player he really was.

The other inside position was filled by the diminutive Bobby Johnstone who was considered by many to be the brains behind the legendary forward line. Johnstone, who hailed from Selkirk in the Borders, made one of his first appearances for the side in a league game against Queen of the South at Easter Road in 1949, in what was the first ever outing in a competitive match by a forward line that would shortly become known universally as ‘The Famous Five’. A two-footed player, ‘Nicker’ was blessed with exquisite ball skills and a great football brain, it was often said that he could open the proverbial can of beans with his educated feet. Capped 13 times for Scotland at full level, Bobby joined Manchester City in 1955 leaving Hibs and the Scottish game much the poorer. At Main Road he would become the first ever player to score in consecutive FA Cup finals in 1955 and 1956. Later in his career he would return to Easter Road, helping the then England International Joe Baker to a record haul of 42 goals in a single season, before leaving to join Oldham after a disagreement with the Hibs chairman Harry Swan. Much to my great disappointment I would miss playing alongside this mercurial talent by only a few weeks.

The legendary Gordon Smith is perhaps rightly acclaimed as Hibs greatest ever player. An integral member of what is still considered by many to be Scotland’s greatest ever forward line, Smith played well over 700 games for the club, scoring 364 goals in all matches while helping his side to three league titles between 1948 and 1952. Later in his career the Scottish International would create his own piece of football history by becoming the first player to win league championship medals with three different clubs, none of them the two big Glasgow sides, before retiring from the game aged almost 40. There is no doubt that Smith, with his film star looks and bewitching ball control was the darling of the Hibs fans, but I only had eyes for one, someone who would also become a great friend in later years, centre-forward Lawrie Reilly. Perhaps he lacked the delicate ball skills of some of the others, but Lawrie would end his career at the almost obscenely young age of only 29 due to injury, as Hibs’ top goal scorer of all time in official games. Nicknamed last-minute-Reilly because of his penchant for scoring late goals, often for Scotland, I can still remember him standing, legs splayed with the ball at his feet, almost inviting the defender to come and try to take it from him.

In our street games or down the local park I was always Lawrie Reilly, and would spend hours on end, often on my own, kicking a small rubber ball against a wall pretending that I was playing for Hibs against Hearts. At the time I had no idea that I had anything special to offer as a football player, although looking back my brother Henry and his friends who were all a good few years older than us, would let both myself and Bobby Nesbit join in their often 12 or 13-a-side games in the local park. I don’t think that would have happened if we’d not been any good. Indeed, although I was still only very small I would regularly take them on and beat them and I’m sure that helped me gain their respect.

Henry was a very good player. He played for the Edina Hearts under-21 side, and would later sign for Hearts. Although he would fail to make the grade at Tynecastle he did manage to play several games for Dunfermline before moving to Berwick Rangers. Later he would become a police officer in Grimsby of all places.

It was only in the final year that the primary school had a football team. We weren’t a bad side reaching a cup final only to lose, but it was after I had moved on to Lasswade High that I really started to take the game seriously. Nearly all of the school side were later selected for trials for the County. About the only two players who were not picked was a lad named George Peden, who would later sign for Hearts, and myself. Ironically, as far as I am aware, we were the only two who went on to play professionally.

Near the end of my schooldays I managed a few games for a local amateur team, but was soon invited to join the Edina Hearts under-17 juvenile side, probably at the recommendation of my brother Henry who at that time was still playing for the under-21s. Edina Hearts were run by a lad called Davy Johnstone who had been on Hearts books at one time and still had connections at Tynecastle and also a guy named Johnny Smart who would later train the Hibs youngsters at Easter Road in the evenings. Unfortunately, at that time I still had the physique of a fag paper seen sideways, and I didn’t get many games. It was only later when I was farmed out to the local Easthouses Boys’ Club and playing against lads of my own age and stature that I really started to come into my own. By then I knew I was good, and playing in my favourite position of inside-left it didn’t take me long to become the best player in the team. I was recalled to Edina Hearts after a player called Fred Jardine left to join Dundee. Jardine would later go on to have quite a good career in the game. Although he would make only a few appearances at Dens Park, Fred would spend almost a decade with Luton Town before ending his career at Torquay United.

I really enjoyed my time with Edina, although I’m not sure if the secretary didn’t rate me or was merely trying to encourage me psychologically, but all he seemed to do was criticise. I was getting better and better however, and before long I was one of the main men in the side. I still lacked a physical presence, but had learned to rely on speed of thought and action to avoid most of the hard tackles that came my way. We had a very good side, winning the league and also the Lord Weir cup in my first season, and from a squad of around 14 or 15 players I think that only two or three did not go on to sign for Hearts. I had not been at Edina long when, probably due to the influence of Davy Johnstone, I was invited along to Tynecastle to train with the youngsters a couple of evenings a week. At this time because I was playing so often I rarely managed down to Easter Road to see the Hibs. Although I do remember after one of our games being extremely upset to discover that they had lost to Clyde in the 1958 Scottish Cup Final. However, for me it was no real problem to be training with the Easter Road side’s greatest rivals or in wearing the maroon and white jersey.

One evening after training I was taken by Davy Johnstone to see the Hearts manager, Tommy Walker, in his office at Tynecastle. I was still only 16, but can vaguely remember signing the piece of paper that was put in front of me without really looking at it or realising just what I was signing. I was far more interested in being informed that I would now be paid £3 per week, money luckily that my uncle Tam insisted that I put directly into the bank.

It was while I was at Edina Hearts that I was capped for the Scottish Juvenile side to play Ireland at Muirton Park in Perth. To say I was surprised to be selected would be an understatement. I believe that someone had called off at the very last minute and that I had been hurriedly called into the team, but I was in extremely good company. Several of the side that evening would later go on to play professionally, including Willie Henderson who would later star for Rangers and Scotland, Alex Ferguson – I wonder whatever happened to him! – and Andy King, who would later join Kilmarnock. I remember being met at the door of the team’s hotel before the game by Ferguson who welcomed me into the set-up and even then he seemed to be the main man. I have very little memory of the game itself, but I still have the framed jersey hanging on the wall at home as a permanent reminder of a very special day in my life.

By now it was time to leave school and no deep consideration was required as far as work was concerned. It was merely accepted that I would follow the family tradition and go down the pit. After passing the basic exam, I started work at the Lady Victoria pit in Newtongrange. At that time, far too young to work on the coal face itself, all the recent school leavers would spend the first few weeks separating coal from the conveyor belt at the surface as part of our training. We did get taken down to see the working conditions at the face where some of the digging still took place by hand, but were never allowed to stray far from the bottom of the shaft, where our job would soon be to couple and uncouple both the empty and full wagons. We were also expected to attend college one day each week, but that didn’t last long as I was thrown out for fighting – only from the college, I have to say, and not the pit. I am not normally aggressive by nature, but for some reason this guy in the class had been niggling me for ages. Finally I snapped and belted him. Funnily enough, as so often happens, we later became great friends.

I was still only 16 and training two nights a week at Tynecastle with the part timers. The legendary former Scotland player Jimmy Wardhaugh who worked for a newspaper during the day, would normally train alongside us in the evenings, as did another first team regular, Billy Higgins. Being young and somewhat impetuous, one night I shimmied Higgins, putting the ball through his legs as he tried to tackle me. The big mistake I made was in going back to try to do it again. This, perhaps understandably, was too much for the experienced Higgins, who clattered into me, only for Andy Kelly, a young player who could look after himself, to step in, remonstrating that I was far too small for that kind of treatment. Jimmy Wardhaugh however was something else. Then approaching the veteran stage of his career, his still mesmerising ball control made him great to watch, and brought back memories of standing on the Easter Road terracing watching him display his magical ball control in games against the Hibs, as incidentally did Willie Fernie of Celtic who was yet another player that I admired greatly.

When I was on the back shift at the pit and couldn’t make the evening training sessions at Tynecastle I would usually join the full timers at Saughton Enclosure on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. One morning there was a full-scale practice match with the first team taking on the reserves. Much to my surprise I was selected to play for the reserve side and found myself lining up at outside-left in direct opposition to right-back Bobby Kirk in a forward line that consisted of the great Gordon Smith, manager Tommy Walker – (who although he was getting on a bit, you could still see that he had been some player) – Willie Bauld and Jimmy Wardhaugh. For a 16-year-old to be playing alongside these legendary figures in the Scottish game was like going to heaven.

At that time Hearts were by far the best side in the country. At the end of the season they would win the league cup and also the league championship for the second time inside three years. After his controversial free transfer from the Easter Road side during the summer, Gordon Smith would not only collect his first ever cup winner’s medal in senior football after Hearts victory over Partick Thistle in the League Cup final at Hampden, but would also win another league championship medal to go alongside the three he had already won at Hibs. Centre-forward Willie Bauld was something special. Although he could often appear lethargic on the field, he had a great football brain and the uncanny ability to place headers with great accuracy. I thought my future team mate at Hibs, Neil Martin, was exceptional in the air, but I have to admit that Bauld was the best that I have ever seen. I have already mentioned ‘twinkle-toes’ Jimmy Wardhaugh who was almost impossible to dispossess on the run with the ball at his feet, a superb master of the dribble. The side was packed with so many exceptional players, including Alex Young who would go on to achieve legendary status on Merseyside with Everton, the fans favourite Johnny Hamilton, goalkeeper Gordon Marshall who would soon join Newcastle and the ever reliable John Cumming to name, but a few.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time at Tynecastle. It was a great experience for one so young and I always received great encouragement from everyone at the club. One morning I was standing outside the ground waiting for the bus to take us to training at Saughton Enclosure. It was an extremely cold day and I was wearing only the thin training gear that had been supplied by Edina when I was surprised to be approached by Willie Bauld who asked if I didn’t have anything heavier to wear. When I replied no, he told me to wait there and in no time at all he came back out with his own tracksuit top. Before I could thank him, my pal Archie Kelly nipped in to say impishly: ‘What a cheek Willie, he’s a Hibs supporter and his hero is Lawrie Reilly. You ought to hear him tearing you to ribbons.’ I could only stand there embarrassed, but Willie just laughed and walked away. He was one of the nicest guys you could ever wish to meet, and what a player.

At Hearts I took part in just the one reserve game, against Hibs of all teams. That evening at Tynecastle I faced several of my future Easter Road colleagues, Desmond Fox who scored a hat trick, Pat Hughes, John Fraser, Duncan Falconer and most notably Jim Scott who would soon become one of my best pals. I was at outside-left in a Hearts side that contained several players with first team experience including goalkeeper Wilson Brown, Danny Ferguson, Billy Higgins, Jimmy Murray and Ian Crawford, but that didn’t stop us from going down to a heavy 6-2 defeat.

The teams that evening were:

HEARTS: BROWN, FERGUSON AND LOUGH, FRASER, OLIPHANT AND HIGGINS, LIVINGSTONE, MURRAY, BLUE, CRAWFORD AND STEVENSON (LISTED AS A TRIALIST).

HIBS: MUIRHEAD, FALCONER AND MACKAY, NICOL, HUGHES AND DAVIN,

FRASER, FRYE, BUCHANAN, FOX AND SCOTT.

It was around this time that a scout from Wolves started to turn up at the house. The English side had just won consecutive First Division championships and with players of the calibre of the England captain Billy Wright, Ron Flowers and goalkeeper Malcolm Finlayson and were a team to be reckoned with. I wasn’t really interested in a move to England, but the scout kept insisting that at least I should come down and look the place over. I still wasn’t interested and it was only when I was told that I could take a pal down with me that I agreed and the next thing I knew both Peter Nesbit and myself were both on the train bound for Wolverhampton. At Molineux we were met by a couple of lads we knew from the Bonnyrigg area who were already on the ground staff who made us welcome. The following day I took part in a wee bounce game that lasted no more than half-an-hour playing alongside Norman Deeley who was then a first team regular. While getting changed back at the ground I was notified that manager Stan Cullis wanted to see me in his office. Cullis, a former rugged England centre-half, explained that although I had been asked down only to look the place over, he had been given a good report by Deeley and he wanted to sign me there and then. Incredibly, I was offered the same basic wage as the first team squad including the current England captain, Wright. I was not sure and asked for time to think it over. As we were leaving the ground my pal Peter asked if I had received any money. We were absolutely skint so I went back and asked Cullis if I would be getting any expenses for my trouble, at which he pulled out a £20 note from a huge wad in his pocket. Although we had barely turned 17, working down the pit we had already been well grounded in the drinking culture that was prevalent among miners and we both immediately headed for the nearest pub and a couple of pints of lager.

Back in Scotland, Edina Hearts were having a good season. We were still involved in several cups and were due to play on the following Wednesday. I was well up for the game, but had been puzzled to receive a letter from the SFA a couple of days before notifying me that as I had signed a contract with Hearts I was now a professional footballer. That evening when I turned up with my boots I showed Davy Johnstone the letter to be told that as I was now a professional I could no longer play for Edina. This was news to me. As far as I was aware the only thing I had signed was a form saying I was to be paid £3 per week. It later turned out that although I was not old enough to do so, the form I had signed earlier had been a full professional form which had been kept in a drawer until I had turned of age, something that was totally against the rules at that time. Although Hearts insisted that they had done nothing wrong they were eventually fined £75 and manager Tommy Walker £150.

My uncle Tam had not been all that keen on me working down the pit and a few months earlier he had contacted Tommy Walker to see if the club could find me a job, a move that may well have meant me remaining at Hearts. Although he had been told by Walker to leave the matter with him, no more was heard about it and I never went back to Tynecastle again as a Hearts player.

The whole sorry saga stretched out over several months during which time I was not allowed to play for anyone. For weeks the event filled many column inches in the back pages of the newspapers, one well known sports reporter, Bob Scott of the Daily Express even started labelling me ‘The Rebel’, a nickname that would stay with me for several years.

It later turned out that Eddie Turnbull who was then the trainer at Easter Road had been well aware of the situation at Tynecastle for some time, and out of the blue one day I was contacted by the Easter Road scout George Smith who told me that he knew I was a Hibs fanatic and asked that if he could get things sorted out would I be interested in signing for the club? I explained about the Hearts contract wrangle, but was told not to worry. The other problem was that I had been receiving £3 each week and would have to pay the money back. Once again I was told not to worry as I would be reimbursed by Hibs.

During the long months of inactivity I had also been contacted by Jimmy Murphy who was then assistant manager to Matt Busby at Manchester United. At that time United were still recovering from the disaster at Munich that had occurred only a couple of years before, but they still had some great players on their books including Noel Cantwell, Johnny Giles and Bobby Charlton. Murphy tried his hardest to persuade me to sign for the Old Trafford side, telling me that perhaps I didn’t realise just how big a club United were. They had obviously had me watched several times, but I was already in enough trouble over the contract situation, and besides didn’t really want to leave home. Murphy tried everything to convince me that I would be making the right move in joining United, but it was only after he finally realised that my mind was made up about signing for Hibs, that he eventually gave up and wished me well in the future. The Aberdeen manager Tommy Pearson also turned up at my doorstep in person one evening, as did the legendary George Young who was then the manager of Third Lanark, but they both received the same answer as Murphy. My mind was made up: I wanted to sign for the Hibs.

It was only much later that I learned I could have taken my pick from almost anybody as there had been a long list of top clubs all keen for my signature. I could well have joined Rangers. Apparently their scout had turned up to watch me one day and later told Davy Johnstone that they would have signed me in a minute, but after seeing the name Edward McConville Stevenson on the team lines he had wrongly assumed that I was a Catholic and left. That didn’t bother me in the slightest. It had taken some time, but at last it looked as if I had achieved my boyhood dream of wearing the famous green and white of Hibs.

I believe that the contract fiasco at Hearts eventually went some way in addressing an anomaly regarding the signing of young players in Scotland. The earlier introduction in England of an apprentice professional scheme had meant that clubs down south could sign schoolboys at 15, while in this country the rules that existed at that time prevented our clubs from signing a boy on a full professional contract until he was 17. This obviously gave an unfair advantage to the English clubs. Possibly because of the Hearts situation, the rules would eventually be changed to bring the Scottish clubs more into line with their English counterparts.

CHAPTER TWO

Signing for Hibs and Disappointment in Rome 1960–61

THE CONTRACT SITUATION with Hearts dragged on all through the summer months and well into the following season while I sat twiddling my thumbs, unable even to turn out for Edina. I just wanted to play football. Hearts themselves had made no contact at all during this time. In their eyes they had done nothing wrong and still considered me to be their player. The Scottish League agreed, but the SFA saw things differently and although I didn’t know it the time I was now a free agent. I don’t know the exact circumstances regarding the contract situation, but the next thing I knew I was being invited down to Easter Road for signing talks.

Extremely nervous, but also very excited, I remember climbing the stairs at Easter Road accompanied by my uncle Tam to meet manager Hugh Shaw and chairman Harry Swan. Unfortunately, it would not be the last time I would be invited up to the boardroom to meet Harry Swan! Hugh Shaw, who had played for the celebrated Hibs side of the mid-1920s that had reached successive Scottish Cup finals before leaving to join Rangers, had been manager at Easter Road since the sudden death of his predecessor Willie McCartney in 1948. During his tenure he had overseen the halcyon post-war days at Easter Road when, fronted by the legendary Famous Five forward line, the club had won three League Championships and had also been Britain’s first ever representatives in the inaugural European Cup in 1955.

Shaw, who was rarely seen without his collar and tie, was a true gentleman in every sense of the word. Perhaps a throwback to a different generation, he rarely took much to do with the day-to-day training itself, leaving that side of things to Eddie Turnbull who had retired from playing to take over as trainer in 1959. Apart from the very occasional visit to the dressing room before training to have a quick word, we would rarely see the manager except on match days.

Chairman Harry Swan, on the other hand, was the main man – Mr Hibs. Along with the secretary, Wilma, he ran the day-to-day operations at the club. Like Shaw, Harry Swan was rarely seen in the dressing room, and if truth be told although he was a small man in stature, he had such a presence that I was probably more frightened of him than respectful. It didn’t take me long to accept the contract put in front of me, full time football and far more money than I had been earning at the pit, but in fact there was never any doubt in my mind that I was going to sign, and I was now a Hibs player.

The first thing I did was to hand in my notice at the Lady Victoria. I was absolutely delighted to be exchanging my pit boots for football boots and almost the next thing I knew I was boarding the early morning bus from Bonnyrigg, bound for Easter Road. By that time the golden years of the late 1940s and early ’50s, when Hibs had generally been recognised as the best side in the country, were well in the past. The club was now in what was, for the want of a better phrase, generally described as in a state of transition. There were still some very good players at a club that had lost only narrowly to Clyde in the Scottish Cup final a couple of seasons before and there was no air of despondency around the place and certainly no lack of ambition.

I was still very shy, but was welcomed by all the senior players who soon made me feel at home, particularly John Grant and Tommy Preston who immediately took me under their wing. Perhaps being that bit older they had recognised immediately that I would be a good addition to their regular drinking school. Grant, who had been capped twice for Scotland only a couple of years before was a particular help to me in the early days. Both he and his defensive partner, Joe McClelland, had been the full-back pairing at the club for a couple of years. John was very strong, could tackle, was good in the air and had a fair bit of pace although his distribution could sometimes let him down. When fit he was probably the best defensive full-back I ever played with.

McClelland was more a rugged type of defender prevalent in the game at that time, although I think that Joe himself often had delusions that he was Maradona. His dad would turn up to watch him every Saturday, and even if Joe hit a bad pass into the crowd, something he did with regularity, he was always ready with an excuse. Nicknamed ‘Walkie-Talkie’ by the rest of the players because he rarely stopped talking, possibly his best ever excuse came after Hibs had been beaten 6-1 by Rangers in a League Cup game at Easter Road. While the rest of the players were down in the dumps after the heavy defeat, Joe was quite happy that the player he had been marking had not managed to get on the score sheet, totally oblivious to the fact that outside-right Willie Henderson had made most of the goals. He was another great lad though, just one of many at Easter Road at the time.

Then approaching the veteran stage of his career, Tommy Preston was still some player. Although a bit on the slow side, he was blessed with a brilliant football brain and had scored many important goals for the club. Another great guy, after he moved back to left-half behind me on the wing, he would just give me the ball and would often say that I kept him in the game for an extra couple of years.

Finally, what is there to say about Joe Baker? Nicknamed Roy-of-the-Rovers by the other players, he had the looks of a film star and was always surrounded by the girls wherever he went. He had a bit of a ruthless streak on the field and didn’t suffer fools gladly, but was a genuinely nice guy who treated everyone the same, whether it was the kit man, Tommy Scotland, or the Lord Provost of Edinburgh. Although I was just a young boy he didn’t differentiate, and treated me no differently from all the other lads. Joe was a one-off. He had it all. Strong, good in the air, fast with the ball at his feet, he could shoot with both feet and could tackle. Although not quite as aggressive as Lawrie Reilly, to my mind he was probably the better of the two and without doubt he was the glamour player at Easter Road.

I arrived at the ground early that first morning full of a mixture of excitement and trepidation and was probably the first in the place. There was no one around to meet me and being extremely shy I just sat in the corner of the dressing room. Probably understanding just how nervous I was feeling, I appreciated the gesture when Jimmy McDonald, an outside-right who had signed from Wishaw Juniors the previous season, came over and introduced himself. Jimmy was great pals with Joe Baker and the pair travelled through from the west each morning. We became good friends, but sadly, although he was a fairly prolific goal scorer for the reserves, Jimmy would fail to make the breakthrough into the first team and would be released at the end of the following season.

As I’ve already mentioned, while working at the pit I had grown accustomed to the drinking culture that was prevalent amongst miners, and even at the age of 15 I would often pop into the local Jug Bar for a couple of pints with my pals. At Easter Road I soon became great friends with Jim Scott, and both Scottie and I would be welcomed with open arms into the post-match drinking school of Tommy Preston, John Grant, Joe McClelland and Ronnie Simpson.

Not long after signing for the club, a couple of mates and myself attended a Sunday night dance at the Bilston Glen Miners’ Club. Obviously someone must have contacted chairman Harry Swan because immediately on arriving at Easter Road the following morning I was informed that I was ‘wanted’ upstairs. I arrived in the boardroom to be confronted by a far from happy Swan who asked as to my whereabouts the previous evening. He obviously knew the answer so I told no lies. Asked if I had been drinking, I replied that I had a few. At that he almost erupted. ‘I’m warning you now,’ he ranted, ‘for years I’ve had nothing but trouble from one player, and I don’t want another.’ A reference, I later found, to the former Famous Five forward Bobby Johnstone, who had left the club in mysterious circumstances just a few weeks before I arrived. I don’t know if Harry thought that Selkirk where Bobby lived and Bonnyrigg were close to each other, but I had never been in Johnstone’s company, although I had heard that he could drink for Scotland. It was his second spell at the club and some of the older players would tell me that Bobby would sometimes be out on the town on a Thursday and Friday evening before a game. Come the Saturday he would often play for just 15 or 20 minutes, but what a 20 minutes, managing to lay on many of Joe Baker’s club record 42 league goals in a single season. However, back to Harry Swan. Suffice to say, being young, the chairman’s advice regarding the perils of drink went in one ear and out the other.

My first ever appearance in a Hibs jersey was in a reserve Penman Cup tie against Cowdenbeath at Easter Road on Wednesday 5 October 1960. I can’t remember much about the game itself except that we drew 2-2, the Hibs goals scored by John Fraser and Johnny McLeod. But if I remember rightly the press were fairly kind to me the following morning suggesting that I had showed promise and could earn a quick promotion to the first team. The Hibs side that evening featured several players who already had, or soon would, feature in the first team, namely:

WILSON, FALCONER AND MCCLELLAND, DAVIN, EASTON AND YOUNG,

MCLEOD, FRASER, BUCHANAN, STEVENSON AND ORMOND.

I already knew goalkeeper Willie Wilson from playing against him for Lasswade against Musselburgh High School, and later for Edina Hearts against Musselburgh Windsor, and had always been impressed. Willie was some keeper, and who knows just how good he would have been, but for a serious back injury that ultimately affected him throughout his career. He had made his debut at the start of the 1959–60 season at Dens Park just days after signing, when he replaced the off form Jackie Wren who had just conceded six in a comprehensive home league cup defeat by Rangers. During only his second first team appearance a few days later he had the misfortune to be in goal when Motherwell’s Ian St John managed to score a hat trick in just two-and-a-half minutes at Easter Road. Nevertheless, Willie had performed well and kept his place in the side. There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that he would have got better and better, but for the back injury received in a game against Dundee a few months later, when according to some he had been rushed back playing before he was ready. In later years he would often make a great save, but struggle to get back for the follow-up. Despite that he went on to give the club more than ten years’ service before leaving to join Berwick Rangers in 1969.

I found John Fraser to be a gem, a great guy who is still a good friend. Although, as his nickname would suggest, ‘Bacardi’ liked a drink, he was not one of the hardened ‘clique’. He had joined the club several years before as yet another potential replacement for the great Gordon Smith before moving back into defence. A very good full-back, he was also more than passable on either wing, and when moved into the centre he could certainly score goals. John served the club well for over 12 years as a player before returning later as trainer to the great Turnbull’s Tornado’s side of the early 1970s.

Willie Ormond was another player that I always had a lot of time for. Although he was well aware that potentially I could eventually take his place, he was always a great help to me in passing on advice and we became great friends, remaining so until his premature death in 1984 aged only 57. Willie liked a laugh and was always joking. He treated the younger players more like a father and one of my favourite memories of him was after the game in Barcelona when he decided to take both Jim Scott and me out on the town. I don’t know if Willie thought that he was looking after a couple of inexperienced youngsters, but at the end of the night the roles were reversed and it was us who escorted him back to the hotel a tad under the weather.

To my mind many people don’t fully realise just how big a club Hibs are. We would often be taken away during the season for a few days training at Gullane, including gruelling sessions up and down the infamous sand dunes, a location the club had been using since the 1920s and long before it was famously ‘discovered’ by Jock Wallace and Rangers in the 1970s. In the evenings we would be let off the hook and a few of us, including Willie and Sammy Baird, would go for a few drinks at a local hostelry. One night Willie asked me what I wanted to drink. Unsure, I replied that I would just have what he was drinking. One gin-and-tonic turned into quite a few and I don’t know yet how we managed to get back to the hotel. I can vaguely remember walking across some fields, it could well have been the golf course for all I knew, before entering the hotel by the back door. Although nothing was said to me personally, in the morning Eddie Turnbull gave both Ormond and Baird a right rollicking. In their playing days Turnbull and Ormond, who both hailed from the Falkirk area, had been great buddies, but I remember Willie telling me later that, ‘The bastard’s changed since he became the trainer.’

It would be easy to give the impression that it was nothing but fun, but all the players took the playing side extremely seriously. After spending time down the pit, for me every day was like a holiday. The only down side as far as I was concerned was the training. I hated training, always had, and always would until the day I retired from the game. Under the eagle-eye of Eddie Turnbull, we would spend hours either running up and down the huge main terracing at Easter Road or sprinting endlessly around the pitch. That may well have been okay for the bigger and stronger boys, but I was still just a slip of a lad and often found it hard going. Eddie however, seemed to have taken a liking to me from the beginning, and sensing that I was struggling, he would sometimes say, ‘Okay Eric, that’s enough for you.’ This would immediately bring the lighthearted comment from Tommy Preston that I was ‘the ‘f***ing teacher’s pet’.

The newspaper article had been right regarding the quick promotion. Just days after my debut for the reserves I was surprised to be taken aside by Eddie Turnbull who informed me that I would be playing for the first team against St Johnstone at Muirton on the Saturday. The club had been struggling since the beginning of the season failing to win any of the previous six games, and had not won since a 6-1 defeat of Airdrie in mid-August. In an attempt to change things, in midweek goalkeeper Ronnie Simpson had been signed from Newcastle United and Sammy Baird from Rangers. Simpson, who had been the youngest ever player to feature in a competitive Scottish game when he lined up for Queens Park against Hibs in 1945, aged only 15, was now reckoned to be at the veteran stage of his career, but he was still some goalkeeper. Although he was not the tallest, he was great in the air and could punch the ball further than most people could kick it. He was also great in one-to-one’s with the opposing forwards, saving the ball with every part of his body including his feet. Like most goalkeepers, Ronnie loved to play outfield during training and was brilliant on the left wing. He also had something of a reputation at penalty kicks, saving six out of six in his first season at Easter Road. Ronnie’s trick at penalty kicks was to stand slightly nearer one post than the other, seemingly by accident, almost inviting the taker to aim for the larger area, which of course Ronnie had already anticipated.