Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In a great Irish tradition of autobiographical fiction that includes James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark, Parker's poignant novel depicts events surrounding the amputation of his left leg as a nineteen-year-old university student. Masterful vignettes present the callow protagonist's life before, during and after this ordeal. Belfast, drear locus of rain and despond, contributes to the heaviness at the novel's heart, as its characters strive to rise above the pervasive melancholy of the city and find some human happiness that they can share. Tosh, Parker's alter-ego, is drifting through life before his cancer diagnosis, plagued by the twin 'cankers' of a puzzling pain in the leg and a crippling loneliness. The amputation forces him into a more authentic relationship with life, which 'Starts with the wound. Ends with the kiss. For the lucky ones.' This remarkable, posthumously edited work, largely written in the early 1970s, prefigures the skills Parker would demonstrate in his plays: plainspoken and stoical in tone, the emotion seeps through a membrane of numb reserve. The writing is impressionistically vivid, the descriptions of pain and discomfort wholly authoritative. Hopdance is a beautiful, sincere, personal testament by a true artist, a wondrous 'lost treasure' of literature now presented to its reading public.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 245

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

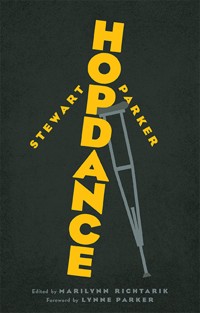

Edited bymarilynnrichtarik

Foreword bylynneparker

thelilliputpress

dublin

Foreword

In 1961 Stewart, my uncle, won his first battle with the vengeful disease that would eventually take his life at the height of his creative powers. Having encountered death while still a teenager he found within himself the resources to live, joyously, in the full awareness of the ‘wave as tall as a ship … creeping soundlessly towards him over the dark water’.

The diagnosis of bone cancer, and the amputation that followed it, happened a few months after I was born. I knew him only in his post-operative state; yet as a small child I had almost no awareness of his physical disability, apart from once glimpsing a prosthetic limb on the stairwell of my grandparents’ house. I was curious, but being as solipsistic as most three year-olds I must have placed the image in a drawer somewhere in my head, and promptly closed it.

In 1964 Stewart left Belfast to take up a university teaching post in America, so our real acquaintance only began in earnest when he returned in 1969. For my sister Julie and me he was chiefly associated with Christmas; a magical, somewhat exotic figure, replete with the stylishness of 1960s New York State bohemia, adding saturnalian spice to a jovial but very ordinary family party. Thrillingly, he would write a short play for us to perform for the rest of the family on Boxing Day. Later, as a fledgling theatre director, I would grow to know him in much greater depth, and have been able to direct his plays throughout my career; his influence on my own work has been profound.

Apart from his very distinctive gait, the image I hold of Stewart is one of warmth, fun, festivity, colour – life. There was never a sense of disability.

Reading this novel now brings me to another image entirely, one apparently at odds with the first, but an essential part of his identity. It brought home to me the effect on my family, their helpless, dogged visits to the hospital, the reference to ‘his brother’s unarticulated anguish’ expressed in the gift of a radio.

After the visceral shock of the diagnosis, the amputation and the – almost more devastating – terror of a recurrence in the other limb, you begin to appreciate the expansive vision that allows him to absorb his trauma and ultimately turn it to use. The intellectually muscular, playfully confident dramatist of Spokesong in 1975, harnessing history to music hall turns, is also the ‘spectral stranger in the corner’ that he describes seeing his amputated figure in the mirror for the first time. His illness and treatment connect him equally to the brute reality of the physical world, and to the netherworld of hospitalization and hallucinogenic pain relief; as he observed, his writing draws on ‘multiplying dualities’. Hopdance focuses clear-sighted, analytical objectivity onto the profoundly vulnerable state of its protagonist. His experience with cancer and amputation did not create this aspect of his personality, but it surely honed its application in his work; and prepared him psychologically to deal with the fragility of his temporal existance.

From childhood Stewart was no stranger to doctors and the rigours of medical treatment. He mischievously parodies their language in his first play, Spokesong, imagining Belfast as ‘a giant body … diagnosis not good’. That playful reference finds its dark counterpoint in the last great speech of Northern Star, when the city has become ‘as maddening and tiresome as any other pain-obsessed cripple’.

The close call with death was to permeate much of his work – the most vivid and direct treatment taking shape in Nightshade, his play about an undertaker who is also a magician, and who is thus practising two forms of illusion. This play, which contains some of his most beautiful dramatic prose, echoes Hopdance; in its connections to Shakespeare and to the biblical story of Jacob, but in particular to the Fair Rosa legend, the tale of the Sleeping Beauty.

A crucial part of its fabric is the gallows humour so bitingly evident in Hopdance – the acid, sardonic wit that Tosh harnesses to control his rage and desolation. Dark comedy is the engine of Stewart’s work, and his weapon against the deadly parasites of piety and sentiment. ‘First he cripples you. Then he gives you his blessing,’ says Delia, the Magician’s daughter. Later she speaks of death, and our inability to deal with it, as ‘an action we perform throughout our lives. And so – at the heart’s core – we are the tribe that has lost the knowledge of how to live.’

The origin of that quest for life and the manner of living – voiced by Delia in Nightshade, articulated and resolved by Marian in his last, majestic play Pentecost – can be traced to Hopdance. This vibrant novel demonstrates the humour and intellectual discipline that enabled Stewart to transcend the death of a part of himself. He went on to achieve a monumental body of work that expressed fully his personality, philosophy and vision. He was the least crippled person I’ve ever known.

My thanks, and those of my family, to Marilynn Richtarik, who has worked tirelessly to capture the complexity of an extraordinary writer. Hopdance, which she has edited with such precision and judgment, gives further invaluable insights in addition to those contained in her perceptive biography. Thanks also to Antony Farrell and Lilliput for this splendid publication.

Lynne Parker, Dublin

Note on the Text

At age nineteen, during his second year as a student at Queen’s University Belfast, Stewart Parker learned that he had Ewing’s Tumour, a rare form of bone cancer. The only effective treatment for it then entailed removal of the diseased limb before the cancer could spread, and so, on 17 May 1961, surgeons at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast amputated his left leg above the knee. Parker remained in hospital for three months, then spent the rest of the summer convalescing at home before returning to university that fall. Desiring fervently at the time to appear merely inconvenienced by his loss, he threw himself back into his old activities with an intensity that left him little opportunity to reflect on it.1 For nearly a decade following his ordeal, however, Parker lived with the uncomfortable knowledge that the cancer could recur. Only when this apprehension had begun to fade could he admit to himself what a heavy burden he had been carrying since his diagnosis, and he decided to attempt to capture in writing the period before, during, and immediately after his hospitalization. As he confided to an interviewer in 1977, he sought to exorcise the trauma by getting it out of his head and onto the page.2 (His protagonist, Tosh, defines the ‘artistic impulse’ as ‘the obsessive need to rehearse your memory of hell’: ‘If you don’t enact it from time to time, it’ll rend out your heart.’) Conversely, he may have wanted to preserve his memories of that phase of his life before they lost their sharp edges. Most of all, though, recording the experience allowed him to structure it for himself in such a way as to endow it with meaning.

In early 1970, Parker began planning a screenplay about his amputation, and he eventually started writing it in January 1971. Likely stymied by the intractably psychological nature of what he wished to convey, however, he never completed more than a few scenes of this. By January 1972, when he returned to the subject, he had probably decided to write his story as a novel instead, although he kept the same title for it: Caution In the Traffic, Prudence In the Rain. (He would not rename it Hopdance until 1974.) Parker finally achieved some momentum on the work early in 1972 after assigning himself a daily quota of 300 words, a tactic intended to help him make headway on his most artistically ambitious projects even amid the pressures of paid work with urgent deadlines. This method of composition, together with the text’s genesis as a screenplay, likely influenced its structure of short, vivid vignettes. He worked on the novel through 1972 and 1973, completing a draft of it in September 1973. Within a week, though, he began tinkering with the order of the sections. From the beginning, he had conceived of the work’s structure as non-chronological – inserting, for example, scenes from before Tosh’s cancer diagnosis between scenes taking place after it – but now he exchanged one non-chronological arrangement for another one, in some cases cutting handwritten scenes apart with scissors and taping them back together in a different order.

Parker began typing what he then regarded as the ‘final draft’ of the novel in October 1973, but managed only a few sections before losing the impetus to continue. In January 1975, having already reached the decision to focus in future on drama, he returned to Hopdance once again and started typing it from the beginning. ‘Can’t make up my mind’, he remarked in his journal:

I’ve spent too long considering it, I don’t know what it’s trying to be anymore. Only thing that’s certain is, it’s too short for publishers. Am apathetic about it for over a year now. Oh, well. Finish and be damned. There are certainly good phrases in it, here and there. Treat it as a daily chore, be done in a couple of months. Thereafter concentrate on plays, I think now my major energy shd. be applied there.

This time, the effort to produce a typescript foundered before the bottom of the ninth page.

Had Parker considered Hopdance to be a commercial proposition, which he clearly did not, he might have managed to finish it at this juncture. In the absence of any financial incentive, though, he felt more enthusiasm about his first full-length stage play, Spokesong, in development at the time. In truth, as he remarked later, the novel’s writing had been propelled by an overwhelming psychological need. Once he had drafted the scenes, however, the sense of urgency deserted him. He put away the manuscript, satisfied that it had served a ‘therapeutic purpose’ for him.3

Although his work life now revolved around play-writing, Parker never forgot about his autobiographical novel, and, at times both of unusual stress and of unaccustomed time for contemplation, his thoughts reverted to it. In late February 1982 (‘On an impulse,’ as he noted in his journal), he ‘re-read passages of Hopdance, & made notes towards completing it. Must do. Somehow. This year.’ Sporadically, over the ensuing months, Parker worked on the novel, making minute changes to the existing manuscript and playing yet again with the order of the scenes. This was the year in which Parker’s marriage, troubled for some time, broke down entirely – partly as a result of his falling in love with someone other than his wife. He was, simultaneously, undergoing a crisis of confidence in himself and his work. He had both the urge and the opportunity to revisit Hopdance, but he lacked the tranquillity necessary to focus on it. By the time he regained his emotional equilibrium the following year, he had entered a particularly frenetic phase of his career as a dramatist that did not abate until the last months of 1987.

In the summer of 1988, Parker returned at last to his novel. He had decided to add several new scenes to it, and he drafted three of these between July and October: Tosh’s conversation with his tutor, Larmour, about Thomas Rhymer; a debate between Tosh and another student about the relative value of literature and political action; and a scene in which Tosh gives a presentation to a group of schoolboys. He also wrote out yet another plan for Hopdance and seemed determined to rework the book from beginning to end. The most recent additions to the manuscript consist of ten word-processed pages representing the first six scenes of the projected final version. In a sadly ironic twist, however, a diagnosis of terminal stomach cancer in September derailed Parker’s progress. Initially told that, with treatment, he might live for another year, he tried frantically to keep working on Hopdance, but, in the event, he died on 2 November 1988, leaving the novel unfinished.

Hopdance has fascinated me since June 1994, when Parker’s executor, Lesley Bruce, allowed me to examine it. I knew the novel had never achieved the apotheosis Parker had envisaged for it, but to my mind it possessed a raw power even in its patchwork state. Although incomplete in Parker’s terms, its form meant that there were no obvious holes or gaps in it. Fragmentary by nature, it readily accommodated new fragments – and could just as easily do without them. It therefore seemed possible to me to produce an edited version of Hopdance that, while not fulfilling Parker’s ultimate vision for it, at least would not do violence to it.

As a writer of experimental prose, Parker wished to challenge novelistic conventions regarding linear structure and character development by illustrating, as he had explained in notes towards an earlier unpublished novel, The Jest-Book of ST Toile, ‘simultaneity of event and stasis of character… pitted against an alarmingly unpredictable universe.’ Since, he had argued then, ‘life is largely lived, not in the present tense, but in the continuous past tense,’ he rejected the idea of ‘a step-by-step narrative’ in favour of ‘a sequence of narrative images which will enact themselves simultaneously in the reader’s mind when he has finished reading them by the intricate way in which they are connected.’ As Parker’s alter ego, Tosh, explains to his friend Harrison in Hopdance, ‘You take the fragments of your past… You fit them into whatever mosaic seems to work. It has nothing to do with time or space’ – except that, in his own case, ‘figments’ might be a more appropriate description of them: ‘I remember single incidents with surrealistic intensity, they never happened the way they replay themselves in my head. Most of them were insignificant at the time. I’ve forgotten all the big production numbers. But these small moments obsess me.’

The non-chronological aspect of the novel apparently became less important to Parker over the course of composition; in successive revisions he often took pains to clarify the time frame of the scenes that depart from chronology through the addition of signposting words such as ‘had’. Nevertheless, the episodes retain the sense of being suspended in time rather than definitively linked in it. Each section of Hopdance has a coherence of its own, but each also gains from association with the others both before and after it, so that individual incidents gain resonance on repeated readings of the book.

The sections of Hopdance that Parker drafted last – as well as those he wanted, but was not able, to write at the end of his life – were designed to make more overt a theme implicit in the version of the novel he completed in 1973. Tosh is adrift before his cancer diagnosis, plagued by the twin ‘cankers’ of a puzzling pain in his leg and a crippling loneliness. As the story of the amputation and its aftermath unfolds, he begins to allow other people to share his suffering and moves closer to being able to make the great connection he has sought to another human being, although most of the time his efforts are misdirected. Like James Joyce does in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, a seminal influence, Parker punctuates Tosh’s process of maturation as a person (notably incomplete by the end of the novel) with his reflections on writing. The amputation, Parker suggests, prepares him to become a serious writer by forcing him into a more authentic relationship to life, which even before his surgery Tosh believes ‘Starts with the wound. Ends with the kiss. For the lucky ones.’ (In a late note about Hopdance, Parker observed that ‘The daemon lover who comes riding over the fernie brae for him is pain.’)

The scenes that Parker wrote or intended to write in the 1980s (labelled, on his final plan for the novel, ‘He was a student of literature at that time’, ‘Fat student on the picket line’, ‘Anybody know ‘Fair Rosa’?’, ‘Country student, Mullan’, ‘Larmour & Brendan’, ‘Minister & Jacob’, ‘The care of posterity is greatest’, and ‘Larmour and the sacred texts’), together with an existing section on Tosh’s proposal for a play about the Ancient Mariner (‘Tosh hadn’t helped his case’), would have allowed him to illustrate Tosh’s developing aesthetic philosophy through analyses of his own ‘sacred texts’, which he described in notes for the novel as ‘Five versions of Sancgreal’. Parker listed and explicated these in another brief note for Hopdance:

Jacob the lame. My condition.

Thomas the rhymer. My calling.

Rosa the fair. My poetic soul.

Brendan the Navigator. My aspiration.

The Mariner. My fate.

References to these narratives – the biblical account of Jacob, the Scots Border ballad ‘Thomas Rhymer’, the story commonly known as ‘Sleeping Beauty’, the legend of St Brendan the Navigator as recounted in the medieval Latin poem Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ – crop up repeatedly in Parker’s other writings, most obviously in his plays Nightshade and Pratt’s Fall, and they were charged for him with deeply personal significance. The overall effect of including extended meditations on them in Hopdance would have been to make the novel more self-reflexively about the creation of art and his own initiation into its mysteries. Notes towards the ‘Country student’ scene indicate that Parker even intended to foreshadow his protagonist’s future vocation as a playwright by having him realize that drama could offer a way of reconciling his contradictory impulses ‘to make a proclamation of my own uniqueness’ and ‘to lose every vestige of signature’.

These late additions to Hopdance would not, however, in my opinion, have significantly changed Parker’s conception of the scenes he had written in the early 1970s. As a rule, he composed slowly and carefully, and the initial handwritten drafts of his works are remarkable for their tidiness. He generally preferred sitting for half an hour without writing a line to forcing himself to set words down that he knew from the outset would only have to be rewritten, if not rethought. When he typed a work he usually revised it, clarifying themes and polishing diction and syntax without fundamentally altering the substance of it. This general predilection was likely intensified in the case of Hopdance, the episodes of which he contemplated for years before ever putting pen to paper. The manuscript bears traces of Parker’s repeated returns to it, but he rarely changed more than a word or phrase here and there on the pages dating from the 1970s. He would certainly have introduced further changes at the typing stage, but I think it unlikely that the final versions of existing sections would have differed dramatically from the original ones. The context of such scenes would be altered by the addition of new ones, but they would keep their initial significance within the story of the amputation while gaining new meanings in the expanded narrative of Tosh’s artistic development.

It thus seemed feasible to me to try to prepare a publishable version of the novel based on the manuscript as it existed at the time of Parker’s death. The first decision I made as editor was to include all the scenes that Parker had drafted, in the order in which they appear on his final plan for Hopdance, although I recognize that the resulting version falls between the one he completed in the 1970s and the one he envisaged in 1988. This struck me as a pragmatic way of honouring Parker’s intentions for the work while acknowledging the limits of my own knowledge and understanding of them.

I address some of these limitations in my appendices to the novel itself. The first three deal with the ordering of the scenes, a subject of great importance to Parker himself. Although non-chronological, the arrangement of the sections was hardly arbitrary. Parker thought about this throughout the process of composition and reconsidered it on several occasions. I have to confess, however, that I do not know why he regarded one ordering as better than another. In the hope that others might be able to infer the logic behind Parker’s rearrangements of the vignettes, I have included his successive plans for the novel in appendices 1 through 3.

Appendix 4 concerns a section labelled ‘The care of posterity is greatest’ on Parker’s final plan. The title matches the epigraph of an essay he wrote on the fifth anniversary of his amputation in 1966 and rediscovered in his study in 1979. This essay is inserted into the Hopdance manuscript, along with another prose piece from 1966 and a much shorter fragment probably written in the 1980s, after the section in the novel that describes Tosh writing an essay on ‘the state of poetry in contemporary society’ just before his amputation. Parker probably intended this section to represent Tosh’s essay, but it is not clear how or if the 1966 pieces would have featured in it. It was, however, apparent to me that the narrative ground to a halt at this point if the 1966 essays and the later fragment were read in their entirety here, so I took the decision to include them all with an explanatory note in an appendix, rather than leaving them in their original forms in the text itself.

Parker wrote Hopdance over a period spanning nearly two decades, during which he lived in both the UK and the US, and, unsurprisingly, the manuscript displays inconsistencies. My work on this edition of the novel began with transcribing what Parker had written as precisely as I could, followed by an effort to standardize accidentals in as unobtrusive a way as possible. Early on, I decided to correct Parker’s spelling where necessary, using the Oxford English Dictionary as my authority, although I preserved Parker’s preference for ‘s’ over ‘z’ in words that could take either. On the other hand, I chose to leave his eccentric punctuation largely alone, knowing that Parker cared deeply about the rhythm of his words and sentences. Occasionally, however, I added full stops at the end of sequences not experimental in form when I judged their omission to be an oversight on his part. After a period of agonized indecision, I decided to treat hyphenation as an issue of spelling rather than of punctuation. I have standardized compounds, which Parker treated very inconsistently indeed, according to the usage in the Oxford English Dictionary. Where the OED gave more than one spelling in bold at the beginning of an entry, I chose the one Parker had used if it were an option. In cases where a compound employed by Parker was not included in the OED, I left it as he had written it.

At the end of his life Parker typed out on a computer the first six scenes of the novel (including both new and old ones), and this word-processed segment provided a template for the layout of the whole. It is, for example, clearer in this word-processed segment than it is on the manuscript pages that Parker typically began paragraphs with a normal indentation. (In the early 1970s, the impecunious young author wrote like someone who did not know where his next pad of paper would come from, with little in the way of margins, so in the manuscript it is often easier to tell where a paragraph ends than where one begins.) I have generally preserved Parker’s idiosyncratic punctuation, including his frequent omission of question-marks, substitution of commas for full stops, and use, following Joyce’s example, of dashes instead of quotation-marks.

Where Parker underlined words in the manuscript, I have italicized them. I have also italicized block quotations, for clarity, and begun each paragraph apart from the first in each section with a normal indentation. I have standardized Parker’s use of dashes when conversational tags or descriptive passages intervene between parts of a speech by a single character, adding a second dash in cases where the interruption consists of more than a few words, and standardized capitalization in a couple of scenes where Parker’s treatment of it varied (the Mariner, the Professor). I have inserted two blank lines between sections of the novel labelled separately on his final plan for it and one blank line to mark breaks within sections.

Throughout the editorial process, my aim has been to present, to the best of my ability, Parker’s words, while minimizing the distraction presented by stylistic inconsistencies. I want the reader’s experience of Hopdance to be that of encountering a new novel by a contemporary writer, so I have avoided drawing attention to my procedures in the text itself, confining such comments to this note and the appendices. I am tremendously grateful to Lesley Bruce and Parker’s estate for allowing me to undertake this labour of love and giving me a free hand in its completion, and to Antony Farrell and The Lilliput Press for making the book available to a general readership. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by Mary Grace Elliott, who painstakingly helped me to check the typescript through several drafts and to formulate the rules by which the work would be carried on, and by Tom McHaney, Bernard MacLaverty, Glenn Patterson, Parker’s agent Alexandra Cann, and my agent Jonathan Williams. I thank Georgia State University’s Department of English, Queen’s University Belfast, the US–UK Fulbright Commission, and the Hambidge Center for Creative Arts and Sciences for funding, time, and space with which to pursue the project, and, as always, I am thankful to Matt, Walker, and Declan Bolch for sharing the journey with me.

1 For an account of Stewart Parker’s cancer diagnosis, treatment, and gradual recovery, see chapter three of my biography of him, published by Oxford University Press in 2012.

2 Caroline Walsh, ‘Stewart Parker’, The Irish Times, 13 August 1977.

3 Walsh, ‘Stewart Parker.’

Epigraph

The foul fiend haunts poor Tom in the voice of a nightingale. Hopdance cries in Tom’s belly for two white herring. Croak not, black angel; I have no food for thee.

PART ONE

I

One day they said, It’s time you went to the gymnasium, Mr. Tosh. And so you go there, whistling even, a shanty of sorts. Trying to fancy yourself aboard ship along these long corridors with the curvy low ceilings, a male nurse in his white smock smiling past like a cabin steward. Polished floor, the right crutch sliding a little. Easy. On a real ship, on these things, with one bound you’d be on your arse. All at sea. There now, wordplay even. Of a sort. The boy is back in his mind again.

Tunnelling left, that must be the place, swing-doors with portholes. Eases his right shoulder between the doors, bundling through in an awkward scuffle, the hospital gymnasium. Bars, ropes, curious engines. Nobody here yet. Heeling round to starboard…

a spectral stranger in the corner lurking there eyeing you out of a ragged thicket of dirty fair hair, lank blue jumper hanging limp on the bony shoulders, metal crutches clamping the forearms, fixing you with that glittering eye, transfixed, don’t look down… gross blue knot dangling in the vacant space where the left leg should be, pyjama knot, dangling from the blunt stump fat with its bandages, the one fat thing, gorged full on its own blood. First sight of it. First mirror.

Easy. As others see me. Scary ghost. Sad freak. No wonder they tried to make you wear their long tartan dressing-gown, get a haircut, stay in the ward, spare the feelings of the healthy, no wonder, horrified eyes sliding sideways as they pass me in the corridor.

Motionless, holding the stare. For the slightest move, confirmed by the mirror, will force him at length to identify with that halt scarecrow which now at last stands there revealed to him after the months of living wholly inside that stricken mask. Caught.

Look.

II

A student of literature at the time, and full of certainties at first. To be nineteen in a warm room, surrounded by books and friendship – the certainties came easy. Outside the window, beyond the great chestnuts and the cultivated lawns, the province yawned along rank and stultifying. On Sundays he could hear the hounds of heaven in the park, a tinny evangelical baying and barking and the whine of hymns, drifting across the damp grey air into his back yard and through the big window to where he stretched across Prudence’s tense body for another bottle of Monk from under the bed. The province was without form and void. Darkness moved upon the face of the waters.

He respected Larmour, his tutor, more than the other lecturers in the Department, though warily and grudgingly, for they agreed on virtually nothing.

—You don’t find the study of literature a sufficiently rigorous discipline in itself, Mr. Tosh, without shouldering an additional responsibility for creating it?