Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

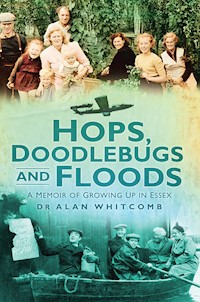

This is the true tale of a boy born into a typical East End family in the Second World War, beginning with his early memories of hop picking and having little money, and moving on to his life in the 1950s and his experience of the devastating east coast floods of 1953. These early memories are the author's own, but what he remembers are a number of events and places that many others growing up in Essex will also recall. This is an entertaining, humorous and nostalgic read for anyone who remembers Essex in the Second World War and beyond.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HOPS,

DOODLEBUGS

AND FLOODS

HOPS,

DOODLEBUGS

AND FLOODS

A MEMOIR OF GROWING UP IN ESSEX

DR ALAN WHITCOMB

To the most important ladies in my life –

Olivia, Lisa-Jane and Jo-Anne.

With thanks for constant love and support.

First published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Alan Whitcomb, 2009, 2012

The right of Alan Whitcomb, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8016 9

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8015 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

ONE:

Straw Sticking in my Bum

TWO:

Floods of Tears

THREEE:

Dead Man’s Bay

FOUR:

Australia Bound

FIVE:

Indecent Exposure

SIX:

The Scum of the Earth

SEVEN:

A Change of Direction

EIGHT:

The Law of Averages

NINE:

School Report

TEN:

Dole to Doctorate

ELEVEN:

Chance Happenings

TWELVE:

Be Kind to Books

Epilogue

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to several people and organisations that have made a contribution to this book:

Firstly my wife, Olivia: she is always the first person to read my work, and she is constructive and encouraging at all times. She is also the one who shares my long periods of isolation while working on a book.

Alfred Price for use of the image of a doodlebug.

The National Maritime Museum and the Museum of London: for permission to use historic photos of Tilbury Docks and women hop picking.

Maureen Reeve, Lisa Chapman, and Josephine Massey: for permission to reproduce family photos.

Geoff Barsby: for allowing the use of some of his valuable photos related to the floods of 1953.

Barbara Carter: who rationalised the many and varied formats of the ancient photos into a single method of presentation.

Nicola Guy and Richard Saunders: my editors at The History Press, who made the final stages of the completion of this book a most enjoyable and painless experience.

And, lastly, the many good people of Essex who shared with me their experience of the war years, hop picking, and the floods of 1953.

PREFACE

Through Hops, Doodlebugs and Floods, I have tried to create a funny, thought-provoking book. It begins with my early childhood as part of a typical East End of London family during the bygone age of the Second World War, and the evacuation of my family out into the relative peace of Essex; I became an ‘Essex Boy’.

Like many ex-London families, we continued our annual exodus from Essex to go hop picking in Kent, even during the war years. Although we picked hops while the war in the air raged above us, there was still much humour that I have related.

My school life seemed blighted by my failure to pass the infamous Eleven-Plus examination, after which it was many years before I put that demon to rest. It was during my school years that I experienced the devastating east coast floods of 1953, during which some of my school friends and their family members lost their lives, but even during that sad event British humour and resolution shone through.

In 1956, I joined the Merchant Navy, illegally at the age of fifteen (through a clerical error!). I spent five years as a seaman and this time broadened my horizons as I grew from a boy to a man. I experienced a brush with danger getting caught up in the Suez War, suffered appendicitis while sailing down the coast of Africa and spent a brief spell in jail in Australia, all at the tender age of fifteen. My service in the Merchant Navy also brought me into contact with British people immigrating to Australia for the princely sum of £10. My memories of my five years as a seaman are full of excitement and all the fun that teenage years should contain.

The need for medical attention for hearing problems led me to a life ‘on land’. I relate here the trials of soul destroying long-term unemployment that eventually inspired me to take on the long slog from limited learning to academic excellence and personal security, with a dizzy rise from life on the dole to a doctorate in just sixteen years.

My meteoric academic development, once it took off, opened a whole new world of career opportunities, including five years at management level with a multinational company, and a long, enjoyable time as a teacher in Essex. This was followed by a satisfying period as a practising psychologist. The spectre of failure and unemployment was finally put to rest!

My entry into the world of publishing was just one result of an amazing number of coincidences that has influenced my personal development. This is my thirty-first book, and my first non-academic publication.

Although this book largely describes my own experiences, I have tried to ensure that you will not be overwhelmed with my personal history. In writing the book my aim was to convey a thought-provoking memoir laced with humour, and a chronicle of what was taking place in Essex at that time.

I hope that you will recognise the trials and progress of a life that you can relate to. We all face tough times in our lives. Hopefully, at such difficult or despairing moments you will be inspired by the trials and difficulties I have overcome, and be inspired by my achievements. Most of all, I hope that you will be thoroughly amused throughout the book.

ONE

STRAW STICKING IN MY BUM

I was born on 24 December 1940. I have tried to practice walking on water ever since, but my family still accuse me of trying to ruin every Christmas since my momentous entry into the world in the middle of an air raid on London during the Blitz. On the way to the hospital, my father had to abandon buses twice because they were hit by enemy incendiary flares, perhaps a forewarning of what my entry into the world implied.

I was born into a typical close-knit extended family of the East End of war torn London. I didn’t have any say in the matter, it just happened. The family relationship was so close, that I grew up not fully comprehending the difference in the relationship between one set of grandparents and the other. They seemed intermingled. Many family activities such as parties, or even moving home, involved many of the extended family.

As a family, we gradually left London during the Blitz of the Second World War, and settled on Canvey Island, in the relative peace of the estuary of the River Thames; I became an ‘Essex Boy’. Some of my aunts and uncles were just a little older than me, and later I was to be in school with them, so it was difficult to view them as aunts and uncles in the accepted sense that is more common today. I became particularly close to two of these young aunts.

One of my earliest memories of life outside of London was watching my father and neighbours creating our Anderson air raid shelter. First an oblong trench was dug. How I yearned to get among that lovely mud! Six steel sheets were inserted into the two widest sides of the trench and bolted together at the top, to form a curved tunnel. The shaped ends were bolted in position, one of which had an opening for the door.

It was at this stage I experienced my first entry to the shelter. It was dark and smelled of damp earth. The next day all the earth that had been dug out of the trench was piled over the sides and the top of the shelter. We were now supposed to be ready to meet the might of the German bombers.

One of the other distinct wartime memories I have as a kid happened in the bungalow we lived in on Canvey Island. I remember hearing a strange buzzing noise that got louder and louder. Then it suddenly stopped and my mum, who was in the room with me, let out a piercing scream and grabbed hold of me tightly. Then, there was a terrific bang. I saw my sister’s pram that was close to the window literally bounce in the air, with her in it. Fortunately, the window didn’t break and shower her with glass.

I was only young during the war years but this incident left its mark on my memory. It was my first experience of a ‘doodlebug’, or flying bomb. It had crashed and exploded not far from our house. Later I became a school friend of one of those injured who survived the blast.

Apart from the memory of the doodlebug hit, there are other wartime experiences that disturb me to this day. One example of this is the sound of an air-raid siren that always makes my stomach turn. After the war, the old air-raid siren continued to be used on Canvey to summon the volunteer fire brigade, or to warn of the danger of flooding. Today, periodically, the siren is tested and is still used to warn of flooding, and it never fails to affect me.

I can recall my mum taking me out into the garden late one night to show me the ‘pretty lights’ in the sky. These were aircraft tracer bullets and anti-aircraft fire. Perhaps she felt I should be rewarded for arriving ignominiously on Christmas Eve and spoiling the family Christmas, not that there was a lot to celebrate that year.

During the war we had a lovely rag-bag of a dog called Prince. He was good company for my Mum and I while my Dad was on Home Guard duties at night. When the bombers thundered overhead causing my Mum and me to quiver in fear, Prince was completely relaxed. However, strangely, he trembled in terror when there was a thunderstorm, which is something that has always thrilled me.

Prince was an Old English Sheepdog, a gentle loveable animal with a will to please. I loved him at first sight, and he, as dogs do, returned my love completely. He followed me everywhere and I soon taught him to do many things. I started by getting him to stay while I walked some way, and only to come when I called him to my side. In due course I taught him to stay while I disappeared from view, and then come and find me, usually on top of the air-raid shelter. But his greatest accomplishment was in playing hide-and-seek. Unlike my other play friends he never tired of being the seeker, although he had the considerable advantage of his sensitive nose.

Some of my earliest and most enjoyable childhood memories are from the hop picking fields of Kent where I was initiated into the traditional ‘holiday’ of London’s East Enders during the war years, and after our move to Canvey Island, we continued the annual migration of Londoners to the Kent hop fields each September. These ‘holidays’ lasted for about four weeks. It has been estimated that the numbers of migrant hop pickers was as high as 100,000 at times.

During the war years there was an absence of men folk who were engaged in war work. Hop picking, or ‘hopping’ as it was usually called, provided a useful contribution to the family income, as well as giving a kind of working holiday. This was the only kind of holiday that many of us could hope for in those days. Not that it could really be called a holiday. Hop picking was backbreaking and messy work, and involved many hardships. But for many ex-hop pickers it is viewed with a sense of nostalgia.

Families would write away to the farms asking for work in the next hop picking season. In due course they would receive their ‘first’ letter, guaranteeing them a place for the next season. Usually families would return to the same farm year after year, and often they would be re-allocated the same hut as accommodation. Sometimes families who were regulars at the same farm would visit ‘their’ hut during the summer before the season started to make it more habitable. The arrival of the ‘second’ letter from the farmer was the signal to join the farm promptly because harvesting was imminent.

Throughout the year, old clothes that would normally have been discarded were collected in the ‘hopping box’. This was a large trunk or tea chest, and it was the repository of the strangest combination of fashion wear. You always wore old clothes while hop picking as they got so stained and smelly from the hops. My pride of attire from the hopping box during my early teens was a pair of horse riding jodhpurs. These were perfect for hiding the ill-gotten gains of a scrumping expedition into the orchards that adjoined the hop fields. Wellie boots were essential footwear for working in the fields and they were worn for most of the hopping season.

During the year food, such as tea, tins of corned beef, and other goodies, would also be saved and packed in the ‘hopping box’, along with blankets and pillows. All necessary cooking utensils would also have to be made ready. Anything that it was thought might come in handy would be packed ready for the mass exodus to Kent.

Prior to the start of the hopping season the hopping boxes would be sent ahead to the farms. They were either forwarded by rail to be collected at the destination station by the farmer, or a lorry driver would be enticed to make a diversion during journeys for their employer. In Kent, the fields where the hops were grown were often referred to as hop ‘gardens’. They were certainly the only gardens many Londoners experienced.

The excitement mounted among the children of hop pickers as the time approached to leave for the hop fields at the end of August for the September season. Sometimes the picking period could extend into October, depending on the weather. This excitement was not only in anticipation of a glorious four weeks holiday, but also in the knowledge that we would miss a further four weeks of schooling following the long school summer holiday. For some families the hop picking season was also followed by fruit picking.

Eventually the time to depart would arrive and the mass migration of hop pickers from their home towns would begin, in my case from Canvey Island. The journey to the hop fields would be undertaken by a variety of means of transport, sometimes with whole families on an open-backed lorry. Fat people were levered on board with much laughter. Old people were perched perilously on collapsible chairs and wrapped in blankets. Lorry journeys involved an exciting crossing of the Thames via the ferry at Tilbury or Woolwich, or the mysterious Blackwall Tunnel. In later years, due to new traffic acts, hoppers were no longer allowed to ride on the backs of lorries and more conventional transport had to be used.

My favourite way of reaching the hop fields was to go by train. For us, it meant travelling into badly war-damaged London to catch the train into wildest Kent. On the journey into London, barrage balloons could be seen, like huge tethered silver whales, floating high above the railway stations, and dotted in the sky along the route into the Kent countryside. Men in the stirring uniforms of the different services were seen everywhere, much to the wonder of children travellers.

The ‘‘Oppers Special’ was invariably a ramshackle train that appeared to have been brought out of mothballs just to carry the hoppers into what we looked on as the wild countryside. This left London Bridge Station in the early hours of the morning on the way to our destination in Kent. The particular train we caught was referred to as ‘Puffing Billy’, but I am sure that was not the real name of it.

Bulky boxes and chests were loaded into the luggage wagon at the rear of the train. In spite of this, all kinds of strange shaped packages were jammed into the carriages, wedged into the luggage racks or supported on laps. The strangest ‘luggage’ I saw in a carriage was a huge lady with a voluminous skirt, from which emerged a little lad like myself who had been made to hide to avoid paying a fare.

Some children, who were older than me, described how they would get past the ticket collector by rushing by and shouting out, ‘Mum’s got my ticket.’ All clever stuff, or so it seemed to me!

On one journey to the hop fields I remember a woman putting her two young children up in the luggage rack, where they slept soundly. I thought this would be an exciting adventure but I was not allowed to achieve such dizzy heights.

It only took a little while for the hoppers to get comfortable for what in those days was a long journey ahead. There were friends from previous seasons to update on events that had taken place over the past year, and new friends to make. During the journey picnics would be unpacked and shared around the carriage. Some of the ‘posh’ people even had thermos flasks!

After a while isolated sing-songs developed throughout the train. These would include current popular songs, as well as ones that belonged to the hoppers. They would improvise from time to time to include the names of other hoppers in humorous rhyme. This would cause much laughter among the travellers. One of the popular songs for the journey was:

Sons of the sea,

Bobbing up and down like this …

This was accompanied by actions, with all of the passengers in the crowded carriage on their feet bobbing up and down. It was amazing that the train managed to stay on the track. Other typical songs sung that were popular with the hoppers were Londoners’ songs such as ‘Doing the Lambeth Walk’ (rather difficult to act out in a crowded carriage) and, of course, ‘Maybe it’s because I’m a Londoner’.

The hop pickers were destined for several different stations along the railway which ran through the heart of Kent. As they left the train at their destinations they were met by a variety of conveyances, provided by the farmers, to take them to their respective farms. At the end of the season the hoppers would re-converge on the ‘Hoppers Special’ for the return to their homes. For the majority of them this meant the East End of London, but for me it meant back to Essex.

When families arrived at their destination station, pandemonium broke out as they searched for their baggage which was in the luggage compartment at the rear of the train. Just when it seemed that the train would be unable to leave for the next station, miraculously, all parcels and trunks were restored to their rightful owner.

Our farmer would take us from the station in lorries or horse-drawn wagons to the common where the hop huts were situated. This was usually on high ground overlooking the lush green hop fields, which in a few weeks would be laid bare by the combined labour of the hop pickers. When arriving at our allocated hut the first task would be to unpack our belongings from the tea chests. These had been packed throughout the year as discarded clothes, toys and other unwanted items were added; at the time of unpacking many forgotten treasures were uncovered. That previously discarded penknife with a broken blade became a very useful addition to my personal store.

The hop huts were made of corrugated iron which formed a long row of connected single rooms. Several such rows would be on one common. Each family was allocated a single room hut, about ten feet square. Sometimes as many as eight people would live in one hut. Often the rooms of related extended families were allocated adjacent to each other, if they were lucky! Some of the regular hoppers tried to make their huts more comfortable by white washing the corrugated iron walls, and by putting up curtains at the door (there were no windows).

The hop huts allowed little privacy within them or between them. All that separated one family’s hut from the next was the ill-fitting corrugated wall. Consequently, all conversations and disputes could be clearly heard in many nearby huts. Flatulence drew much mirth to neighbours and embarrassment to the sufferer.

In the darkness of the late evening disjointed, quiet-voiced conversations passed between the women from one darkened hut to another, ‘Do you remember, Mol, when your ol’ man blew all his wages on that set of encyclopaedias?’ ‘Yeh, silly sod. Pointless really. We’ve sold em now. He reckons he knows everything anyway, so why did he bother?’ – ‘Lil, do you remember all the fuss your Bert made when he found out you’d pawned his fob watch?’ ‘Nah, us married women should forget their mistakes, there’s no point in two people remembering the same thing – men never forget!’

Another amusing conversation was taking place between Ada and Betty. Ada and her husband, Sid, were elderly and had occupied the same hut for years. Sid was a surly sod and too old for war service. Betty Knowles was a relatively young woman with two children, and it was her first season hop picking.

‘Is Mr Knowles here?’ Ada called across the croaking frogs of the night. ‘If he were he’d be a sensation,’ Betty replied. ‘He’s been dead for four years.’ ‘Oh dear,’ Ada said, ‘What have I said, I’m sorry.’ ‘Don’t be silly,’ Betty retorted, ‘I’m not bothered, so why should you be?’

‘I sometimes wonder which is worse, divorce or death. After all, people do sometimes get back together after a divorce,’ Ada ruminated seriously. ‘It’s difficult to get back together after death, thank God,’ Sid acidly commented.

‘Well we were both,’ said Betty. ‘We divorced, and then he died. Neither was particularly upsetting for me!’

Nobody complained about these late night conversations, no matter how late. Eventually they subsided as the occupants of the huts fell asleep.

Each hut had about one third of its area allocated to a ready built wooden platform which served as a communal bed for all the family. Every family was allocated a bale of straw. This was spread on the platform to form bedding. The more enterprising hoppers took along large sacks like mattress covers (‘ticks’) which they stuffed with straw to form a kind of mattress.

We had a single acknowledgement of luxury in my grandmother’s hut. This was a rag rug that adorned the rough concrete floor of the hut. It was multi-coloured with no set pattern. You could say it was abstract, but more likely ‘distract’. My grandmother had made it out of bits of old clothes. It was backed with sacking that still smelt of the dried hops it once contained.

My first experience of hop picking was at the age of four when I accompanied my grandmother and my aunts, who, as mentioned earlier, were not a lot older than me. My mother was obliged to stay at home with my younger sister, and my father was engaged in war work. We went to a farm that we called ‘Clover Field’. This initiation into hop picking took place in the years of the Second World War.

At first the novelty of sleeping five or six in a big bed was exciting. Later I was not so sure. The room was lit by a hurricane lamp which conjured up all kinds of frightening monsters on the walls. These were cleverly dispelled by my aunts who had the dexterity of creating friendly shadows such as rabbits and birds with their hands.

No sooner had I got over the terror of ogres on the walls than a new nightmare began; the orchestra of frogs croaking. My aunts’ assurances were of little avail once a hysterical scream was heard from several huts away. This was followed by a plaintive wail, ‘Bloody hell, Dolly, there’s a frog in my bed’. Aunt Rita was quickly despatched by my grandmother to rescue the poor lady from a fate worse than death.

For the first few nights of sleeping the straw tended to be spiky because it was new. As a tot with a tender rear end, I was continually complaining, ‘There’s straw sticking in my bum, Nan’, much to the amusement of the occupants of the nearby huts. This was the signal for my aunts to bounce up and down on my part of the bed to break the straw down. Later our bedding became more comfortable with continual use, but towards the end of our stay it was more compact, hard and less restful, but always beautifully warm.

Cooking took two forms; on primus stoves or on open fires. High-tech families had a primus stove which could be used inside the huts. These always terrified the life out of me. They consisted of a brass chamber that was filled with paraffin oil. The chamber had a pump which was used to increase the pressure in it and cause the paraffin to be pushed out in a fine stream through a minute hole in a protruding stem. But the stem had to be hot in order for the paraffin to vaporise as it left the chamber. This was achieved initially by burning a lip full of methylated spirit around the stem until it was hot. Pumping the paraffin through the hot stem created a fine vapour that could be lit, achieving a fierce and roaring economical flame. But many people ended up with singed eyebrows and hair as a result of lighting the paraffin before the methylated spirit had done its job. Primus stoves were even operated by young children then. Most people today would be appalled by children being exposed to such a danger, especially in the confinement of rows of connected huts.

Most cooking took place on open fires outside the huts, when weather permitted. Each hut had its own open fire cooking arrangement, which merely consisted of an iron bar supported across a wood fire by a metal stand. There were also communal cooking areas between groups of huts. These were more substantially built, often with a tin roof affair to give some protection from the rain, but still largely open to the elements.

‘‘Opping pots’ were essential hop pickers’ equipment. These were heavy iron cauldrons that were positioned on the cooking pole by strong ‘S’ shaped hooks. The fires were made from brush wood called ‘faggots’. The latter were provided by the farmers in a communal pile some safe distance from the huts. It was the job of the children to ensure that a ready supply of faggots was kept by their hut.

The most common main meal fare for hoppers was stew which everyone, even children, could produce. Variations in taste were achieved by using different meats, e.g. bacon hocks, lamb, and corned beef. Local rabbits were a favourite, if one didn’t question too deeply how they were obtained! Chicken was considered too expensive a meat to be used in stew. Mushrooms were abundant and free in the local fields, and the illicit raids on the farmer’s onions and other vegetables were considered fair game and a source of cheap food. There was an abundance of wild herbs for those knowledgeable enough to recognise them.

The leftovers from one day’s meal was left in the cauldron and added to the next day with further ingredients. From day to day meats and vegetables and herbs and spices would be added to vary the flavour. By the weekend the mixture had become a confusion of taste and the cauldron would be completely cleaned out to start a new week. A particular luxury I enjoyed was a jacket potato cooked to a cinder in the open fire, and the tasty inside scooped out. The art of eating a hoppers jacket potato was being able to eat the flesh, without getting any cinders in your mouth.

All water was obtained from standpipes situated at various places around the site. It was, usually, the task of children to collect the water in a variety of containers. By the time we got back to the hut with our buckets of water, our wellie boots were also awash inside. For me the standpipes were important meeting places with other children when we devised all kinds of devilment which invariably ended up with us soaking wet.

The communal toilets (often referred to as the ‘thunder box’ – for obvious reasons!) were a crude and unsanitary arrangement set up at a discrete distance downwind from the huts. They consisted of small corrugated adjoined privies with a wide wooden plank and a hole positioned over a large tin drum, which was emptied periodically by the farmers. Male and female used the same toilets (can you imagine the cries that would come from the European Parliament today?), and the only concession to privacy was a bolt on the door. There were no windows and despite the considerable gaps in the doors and walls, the smell was overpowering in hot weather, and was only slightly alleviated by the crude disinfectant and other chemicals used. Perched on the wooden plank seat, with my feet dangling well above the floor, I was always terrified that I would fall through the hole and into the smelly drum below. Bum balancing became a fine art!

Each morning the hoppers awoke early. First there was the procession of chamber pots and overnight buckets to the toilet for emptying. These were followed by visits for ‘sit downs’. The majority of those going to the toilets clutched roughly torn squares of newspaper. The more well-to-do marched down the hill proudly displaying toilet rolls.

The less hardy people would wash inside the huts, perhaps with the luxury of a bowl of warm water. The more seasoned campaigner washed out in the open with cold water. This was followed by a quick and basic breakfast. Next was the important task of preparing sandwiches and drinks for the day. These were essential to keep us going while we were working in the hop-fields. The standard drink was orange squash made from National Health Service supplements for children.

A typical hop picking morning started early with a cold damp sunrise, and the morning mist still hovering. Spiders’ webs hung heavy with dew, and the smell of the fires outside the huts hung in the air. A nippy breeze assured you that the winter frosts were not far away. By eight o’clock in the morning everyone had to be assembled in the hop fields, but there were rarely latecomers because this was why the hoppers had really come - to earn a meagre supplement to their normal income. A hard-working adult could earn about £12 during the four week’s picking.

On the first day of picking there was an early morning ‘briefing’, when the families were allocated the bins into which they would pick the hops. At this time we would also be told the rules the farmer wanted followed, e.g. no raiding the fruit orchards, and the ‘tally’, which is the payment per bushel of hops picked, e.g. four bushels to the shilling. Sometimes the tally became a subject of heated argument between the pickers and the grower when it was considered that the tally was not fair. At this time the pickers would also be warned about picking ‘dirty’ hops. This referred to having too many leaves in the bin.

The hop ‘bines’ grow from a crown sending up tendril-like growths. Each hop plant had four harsh sisal strings spreading out vertically like a square cone, with the widest spacing at the top. These stretched up to a combination of upright and diagonal poles set in rows, and criss-crossed with a network of overhead wires. The bottom three feet of strings were constrained by a horizontal string called the ‘cradle’. Four tendrils of hop bines were trained up each string, resulting in sixteen stems from one mature hop plant. When I first went hop picking, much of the preparation of the supports for the growing hops was carried out by farm workers on stilts. Who needed to go to a circus when there were so many versatile farm workers around us?

Hop bines carry rich clusters of green cone-like flowers, rather like grapes on a vine. They form a forest-like growth of lush green, towering to a height of twelve feet. The bines have coarse, hairy branches that scratch wherever they touch the skin. The bines stretch in long straight lines, or ‘alleys’, the length of the hop field, forming a seemingly impenetrable jungle. At the start of the picking each hop row looked like a long green tunnel of leaves with the pungent smelling hops glistening with the morning dew or overnight rain.

The hops were picked into a large ‘bin’, although on some farms they were picked straight into bushel baskets. The bin was about seven feet long and consisted of two ends made of crossed pieces of strong wood, and joined by two sturdy wooden side rails, extended at the ends to form ‘handles’ which were used for moving the bin. The side rails supported a long sacking bag to form a kind of trough some three feet wide. These trestles were strong and stable enough to support four adults sat on each corner whilst they picked the hops into the bin. They were light enough to be moved along the rows of hops by two people, but to move it when fully loaded with hops required the combined strength of four adults. One bin would be used by an entire family.

The hop pickers moved along the maze of rows, pulling on the coarse bines until the string broke, allowing the coarse hairy bines to fall, showering the hoppers with water from the overnight rain and dew, pollen, and all kinds of insects. Several bines would be pulled down to be draped across the hop bin. All who were old enough were expected to pick the silky, sticky, green-yellow hops. Children not tall enough to reach the bin side rails would be given a box or an upturned umbrella to put their picked hops into.

Sometimes a bine, or the string supporting it, would stubbornly refuse to break. This was the signal for as many children as possible to swing on the vine together until the string broke, dumping the kids in an untidy heap of giggling bodies on the ground. When a bine still refused to come down a worker, called a ‘pole puller’, was summoned. He would use a long pole with a sharp hook on the end to cut the offending overhead string.

The hop picking family would work along between the rows of bines, picking off the flower heads, and trying to avoid getting too many leaves in the bin. During the picking the thumb and forefinger became blackened by the pale green flowers. This was caused by the pollen or by the chemicals the farmers sprayed on the hops. This blackening tasted bitter, in a way similar to the taste of the residue left from picking tomatoes.

There were no toilets out in the hop fields. The procedure for ‘going’ was to walk some way ahead of the pickers and squat in the rich leafy lanes ahead where there was some privacy. The problem was that in due course the pickers would eventually arrive at the same spot as they progressed along the alley. Then it was a case of ‘tread carefully’.

Children old enough to do so picked alongside their mothers, whilst younger ones might be lucky enough to be given the glorious freedom of wandering among the bines playing hide and seek. For me the greatest pleasure was to wander alone among the quiet leafy green aisles. It seemed like a fairyland where one was cut off from civilisation. The ringing of a bell was sure to bring all the children to their mother’s side. The bell announced the arrival of the lollipop man. If the day’s work had been pretty successful then you might be rewarded with a lollipop, a mint humbug, sherbet dabs or aniseed balls.

During the war years I was fortunate to be considered too young to pick hops alongside the adults, so I was left very much to my own devices. Whilst the young girls tended to search for pretty pieces of broken glass and china, the boys would explore the local countryside. I spent many happy hours wandering in the local woods, where the fruits of nature, such as nuts, apples and blackberries, sustained me throughout my travels. There were also treasures to be collected and taken back to show the adults. My favourite trophies were spent shells and shot off pieces of the aircraft that could be seen engaged in battles high above the fields of Kent. The pickers carried on picking even during air raids.

As enemy aircraft flew overhead, we could see the puffs of smoke that surrounded them as they flew through the anti-aircraft fire. After such an event the fields were frequently littered with shrapnel and all sorts of evidence of the attack, which were exciting prizes for children to find. Apart from spent shells and bits shot off aircraft, one of my most exciting finds was a substantial chunk off a magnetic mine.

The hop-fields were situated in what later became known as ‘Doodlebug Alley’; the flight path of the rockets aimed at London. On one occasion, during the later years of the war, there was all the usual banter going on between the pickers, then suddenly they all went silent and the ominous sound of a doodlebug penetrated the silence. Everyone waited for the fatal time when the engine of the rocket would stop, signalling the ultimate disaster for some poor soul. Then a young girl from London began screaming uncontrollably from the memory of horror the sound brought back to her. The incident also served to remind me of my own recent experience of a doodlebug.

After the war I went hop picking with my parents and my brother and sister. My father would work at the Ford Motor Company in Dagenham during the week, and then he would come to see us at weekends, often cycling all the way from Essex to the hop farm to save on the train fare. We were not wealthy enough to buy one of the cars he worked all week producing.

During one winter we had to abandon a planned visit to our hop hut to prepare it for the next season. It was January of 1947, which was the worst winter on record at that time. Even the River Thames froze that year. Just walking from our back door to the street was an enormous task for my little seven year old legs, so deep was the snow. It was impossible to see where the side of the road ended, and even more importantly where the dykes by the side of the road were.

During the picking season on the farms, lunchtime would usually be spent in the fields sitting on a pile of stripped bines, munching on sandwiches, and trying to avoid too much of the bitter-tasting hop blackening getting into your mouth. But, no matter what the filling of the sandwiches was, the bitter taste of the hop pollen disguised it completely. A few people would wear rubber gloves while picking, but these were the exception as most people agreed that wearing gloves slowed down the amount you were able to pick.

Tea would be available to those fortunate enough to own a thermos flask. Often pickers would mix up tea containing milk and sugar in a ‘billy can’. This would then be heated up on an open fire in the field. We didn’t have a flask for tea, and sometimes it wasn’t convenient to light a fire in the fields, for example, when it was raining. One of the answers was to make tea in the morning and put it in a stone hot water bottle, and then wrap it in a towel to keep it warm until tea break time.

Sometimes a ‘well-to-do’ hop picker was fortunate enough to have a portable radio to play in the fields, and all could hear the familiar sound of Workers Playtime, introduced by the classic theme music of Eric Coates, ‘Call your workers’.

During the day, farm workers would go behind the pickers and cut off the stripped bines near the base. These would be carried away by wagons drawn by huge shire horses or tractors. Children moved around the horses seemingly oblivious to any danger. However, I was always timid when near them and this fear has remained with me through to adulthood. The final view of the picked and cleared field looked like an area that had been attacked by locusts.

Late in the afternoon a crew of farm workers, called ‘tally-men’, would come round to measure the pickings of each family. This was a time of abuse and ribald comments. The hops were measured using a bushel basket. The ‘tally’ for a bushel of hops was set at the start of the season, and the rules were that hops should be picked free from leaves, although this was impossible to achieve and a compromise quality was the realistic aim. The bushel basket was scooped into the bin and each full one was tipped into large sacks called ‘pokes’, thus measuring the picker’s output and income.

Before the tally-men arrived the pickers would try to fluff up their hops so that they would take up as much room as possible in the basket. When a tally-man was considered too heavy handed in pushing his basket into the hops he would be cursed by the hoppers for deliberately crushing the flowers and reducing the overall quantity. The tally-man would often be told to do something impossible to himself! It was uncomfortable to pick hops when it was raining, but when they were wet they made a bigger quantity in the measuring baskets because they were so swollen by the dampness. To some extent, this compensated for getting wet while picking.

The process of scooping out the flowers was overseen by the team foreman, or even the farm owner himself. He would count the bushels of hops and record the tally for each bin, adding it to the previous total. Sometimes the foreman would refuse to allow a bin to be emptied because it contained too many leaves. The family would then be left to clean out as many leaves as possible before the tally-men finished their rounds. To be told that their hops contained too many leaves offended the pride of the hoppers.

In the early days of my hop picking experience, horse drawn carts were used to transport the large sacks (called ‘pokes’) containing the hops to the kilns. Later the horses were replaced by tractors. At the kilns the hops were dried by charcoal or oil fired heating. We children were not allowed into the kiln areas, but I was once given the chance to see what went on there. However, I found the heat and the smell too over-powering to ever want to visit again.

One of the things I hated about hop picking was the great big caterpillars which looped over the bines and dropped on us. One clever Dick said that they belonged to the hawk moth. This knowledge did not reduce my revulsion of these creatures.

When children had picked what was considered their quota of hops as a contribution to the family’s collection, usually by lunch time, they were allowed to go off and amuse themselves. This was a time when the hop garden resounded with the sound of children at play and engaging in adventures that only children can conjure up. This was a time when the mothers would gossip to neighbours and friends picking nearby.

The picking days were very long. Although we had to be on the field by eight o’clock, we were often on there as early as seven in the morning, and rarely stopped work until the whistle blew at four in the afternoon. The call would then come to ‘Pick no more bines’ and the day’s picking was over. Children were called back; coats and other things were gathered for the tramp back to the common, the huts, and the evening meal.

In the evening there was a lot of good-natured banter and singing around the fires. Sometimes there would be someone who could play the accordion or a mouth organ, and this was sure to get the singing going. But, to be honest, it didn’t take much to get the friendly hoppers joking and singing.

A visit to the local shop always interested me, not only because of the wide range of things sold, but I was also fascinated by the wire mesh in front of the shop counters. At home I only saw this wire mesh in the local Post Office, but here all of the shops seemed to have it. It was not until many years later I found out the reason for this. Normally, prior to the hopping season, merchandise would be stacked outside on the pavement in fine weather, and many items hung for close inspection around the shop to tempt shoppers. However, once the hoppers arrived in the area all goods were protected behind the counters and wire mesh partitions. Hoppers were not to be tempted – or trusted!

Being sent to the shops was for me an occasion for adventure. We always chose the most torturous of routes. Scrambling along a narrow alley behind a barn, wading through a running stream, hurtling across the field where the supposedly ‘wild’ bull roamed. We followed any route other than the easy way, by road.

We would arrive at the shop dirty and dishevelled, in holey jumpers and trousers, and wearing our ever present wellie boots. It was hardly surprising that the shopkeepers treated us with disdain and suspicion. One day I returned from a shopping expedition with one of my aunt’s bearing a crusty loaf. Our hunger got the better of us on the return journey and we had picked out the inside of the loaf, leaving a crusty shell. We were incredulous that no one would believe us when we said, ‘The mice must have got at it.’

I loved the camaraderie that abounded among hop pickers, and this was particularly apparent at night time. In the evenings the common area of the huts site glowed with the many fires outside the huts and, if the weather was reasonable, all the families would sit around the fires on homemade stools chatting. This was a time when children were allowed to experiment in cooking toast, baked potatoes, and apples pinched from the local orchards. A special evening treat was a mug of dry baby milk powder mixed with cocoa and sugar and eaten dry, again, courtesy of the National Health Service.

Scrumping was considered a normal extension of hop picking and, try as he might, the farmer couldn’t possibly prevent it. When I was about ten years old and working on a hop farm in Kent, I initiated my younger brother and sister into the noble art of scrumping. One day, when we were returning from a scrumping expedition, we were challenged by the farmer. ‘Have you been scrumping in my orchard?’ he demanded. Our denial was promptly followed by a cascade of fruit bursting out from the bottom of my trousers; the contraband had been hidden in my trouser legs which had not been, as I thought, firmly tucked into my wellie boots! We took flight and spent the rest of the day worrying that the farmer would turn up on the common and send our family home in disgrace. But it didn’t happen.

The real experts at scrumping were the gypsies who frequented many hop farms. They extended their haul of illicit food to chickens, eggs and rabbits, or so I was told by the adults. They were regarded with suspicion by hoppers and farmers alike, but they were hard workers. They would continue to pick in all weathers, even heavy rain. For this reason their work was held in high regard by the farmers. The other pickers would also work during the rain, but tended to do so with less enthusiasm than the gypsies.

The gypsies usually occupied a section of the common separate from the other hoppers. Often they would make up an area with their own caravans rather than use the huts that were available. Although many of the hoppers were wary of them, I got on well with them.

Romany families were present on most hop farms. Many would meet and stay for the whole of the season, which was longer than just the hop picking period, and continued into fruit picking. They always seemed a proud race to me and did not appear to mix readily with the rest of us pickers. Some people were hostile towards them but I found them both mysterious and interesting, and I spent a lot of time safely in their company. They taught me how to find the appropriate leaves which could be rubbed on my legs to instantly dispel the discomfort caused by stinging nettles, which grew in abundance around the hop fields. Their life was far from easy and they always seemed to work with a greater intensity than the rest of us. But whatever hardships their way of life entailed, it always seemed to me that they were compensated with a greater degree of freedom.

The gypsies had many words that were special to them. They used to call me ‘chavvie’ (child) and their teenage children ‘chie’ (young woman) and ‘rai’ (young man). My family were referred to as ‘gorgio’ or ‘gorgie’ (non-gypsy) and the gypsy home as ‘vardo’ (caravan). They told me what seemed wonderful tales of their life on the ‘drom’ (road). It all seemed exciting to me and was further enhanced by their strange words. But I also learned of their aversion to the word ‘diddecoi’, which was used by many of the hoppers to refer to gypsies. I learnt that this was really a derogatory term for gypsy implying a half-breed.

You either loved hop picking or you hated it. In the morning it was generally cold, and you got wet with the dew as the bines were pulled. In the afternoon it tended to get hot, so you often got burnt by the sun. When you got back to the hut you were tired and dirty, and there was no bath to soak in and freshen up. A strip wash, hopefully in warm water, was the best to hope for.

The weekends were important times because this was when many husbands and fathers would come to visit, especially during the war years when those engaged in reserved occupations would come to see their family. Picking, if it took place at all, finished early on Saturday. This was a time to visit local shops and go to the Saturday matinee at the local cinema. In the evenings there would be a walk to the local pub, where we children sat outside with our lemonade and a bag of crisps.