9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

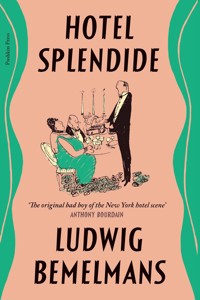

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In this uproariously funny memoir, Ludwig Bemelmans uncovers the fabulous world of the Hotel Splendide, the luxury New York hotel where he worked as a waiter. With equal parts affection and barbed wit, he records the everyday chaos that reigns behind the smooth facades of the gilded dining room and banquet halls.In hilarious detail, Bemelmans sketches the hierarchy of hotel life and its strange and fascinating inhabitants: from the ruthlessly authoritarian maître d'hôtel Monsieur Victor to the kindly waiter Mespoulets to Frizl the homesick busboy. Illustrated with his own charming line drawings, Bemelmans' tales of a bygone era of extravagance are as charming as they are riotously entertaining.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

I

The Animal Waiter

The day was one of the rare ones when Mespoulets and I had a guest at our tables. Most of the time I mugged into a large mirror in back of me. Mespoulets stood next to me and shook his head. Mespoulets was a waiter and I was his bus boy. Our station was on the low rear balcony of the main dining-room of a hotel I shall call the Splendide, a vast and luxurious structure with many mirrors which gave up its unequal struggle with economics not long after the boom days and has since most probably been converted into an office building or torn down.

Before coming to America I had worked a short while in a hotel in Tirol that belonged to my uncle. German was my native language, and I knew enough English to get along in New York City, but my French was extremely bad. The French language in all its aspects was a passion with Mespoulets, and he had plenty of time to teach it to me.

‘When I say “Le chien est utile,” there is one proposition. When I say “Je crois que le chien est utile,” there are two. When I say “Je crois que le chien est utile quand il garde la maison,” how many propositions are there?’

‘Three.’

‘Very good.’

Mespoulets nodded gravely in approval. At that moment Monsieur Victor, the maître d’hôtel, walked through our section of tables, and the other waiters nearby stopped talking to each other, straightened a table-cloth here, moved a chair there, arranged their side towels smoothly over their arms, tugged at their jackets, and pulled their bow ties. Only Mespoulets was indifferent. He walked slowly towards the pantry, past Monsieur Victor, holding my arm. I walked with him and he continued the instruction.

‘“L’abeille fait du miel.” The verb “fait” in this sentence in itself is insufficient. It does not say what the bee does, therefore we round out the idea by adding the words “du miel”. These words are called “un complément”. The sentence “L’abeille fait du miel” contains then what?’

‘It contains one verb, one subject, and one complement.’

‘Very good, excellent. Now run down and get the Camembert, the salade escarole, the hard water crackers, and the demitasse for Mr Frank Munsey on Table Eighty-six.’

Our tables – Nos. 81, 82, and 86 – were in a noisy, draughty corner of the balcony. They stood facing the stairs from the dining-room and were between two doors. One door led to the pantry and was hung on whining hinges. On wet days it sounded like an angry cat and it was continually kicked by the boots of waiters rushing in and out with trays in their hands. The other door led to a linen-closet.

The waiters and bus boys squeezed by our tables, carrying trays. The ones with trays full of food carried them high over their heads; the ones with dirty dishes carried them low, extended in front. They frequently bumped into each other and there would be a crash of silver, glasses, and china, and cream trickling over the edges of the trays in thin streams. Whenever this happened, Monsieur Victor raced to our section, followed by his captains, to direct the cleaning up of the mess and pacify the guests. It was a common sight to see people standing in our section, napkins in hand, complaining and brushing themselves off and waving their arms angrily in the air.

Monsieur Victor used our tables as a kind of penal colony to which he sent guests who were notorious cranks, people who had forgotten to tip him over a long period of time and needed a reminder, undesirables who looked out of place in better sections of the dining-room, and guests who were known to linger for hours over an order of hors d’œuvres and a glass of milk while well-paying guests had to stand at the door waiting for a table.

Mespoulets was the ideal man for Monsieur Victor’s purposes. He complemented Monsieur Victor’s plan of punishment. He was probably the worst waiter in the world, and I had become his bus boy after I fell down the stairs into the main part of the dining-room with eight pheasants à la Souvaroff. When I was sent to him to take up my duties as his assistant, he introduced himself by saying, ‘My name is easy to remember. Just think of “my chickens” – “mes poulets” – Mespoulets.’

Rarely did any guest who was seated at one of our tables leave the hotel with a desire to come back again. If there was any broken glass around the dining-room, it was always in our spinach. The occupants of Tables Nos. 81, 82, and 86 shifted in their chairs, stared at the pantry door, looked around and made signs of distress at other waiters and captains while they waited for their food. When the food finally came, it was cold and was often not what had been ordered. While Mespoulets explained what the unordered food was, telling in detail how it was made and what the ingredients were, and offered hollow excuses, he dribbled mayonnaise, soup, or mint sauce over the guests, upset the coffee, and sometimes even managed to break a plate or two. I helped him as best I could.

At the end of a meal, Mespoulets usually presented the guest with somebody else’s check, or it turned out that he had neglected to adjust the difference in price between what the guest had ordered and what he had got. By then the guest just held out his hand and cried, ‘Never mind, never mind, give it to me, just give it to me! I’ll pay just to get out of here! Give it to me, for God’s sake!’ Then the guest would pay and go. He would stop on the way out at the maître d’hôtel’s desk and show Monsieur Victor and his captains the spots on his clothes, bang on the desk, and swear he would never come back again. Monsieur Victor and his captains would listen, make faces of compassion, say ‘Oh!’ and ‘Ah!’ and look darkly towards us across the room and promise that we would be fired the same day. But the next day we would still be there.

In the hours between meals, while the other waiters were occupied filling salt and pepper shakers, oil and vinegar bottles, and mustard pots, and counting the dirty linen and dusting the chairs, Mespoulets would walk to a table near the entrance, right next to Monsieur Victor’s own desk, overlooking the lounge of the hotel. There he adjusted a special reading-lamp which he had demanded and obtained from the management, spread a piece of billiard cloth over the table, and arranged on top of this a large blotter and a small one, an inkstand, and half a dozen pen-holders. Then he drew up a chair and seated himself. He had a large assortment of fine copper pen-points of various sizes, and he sharpened them on a piece of sand-paper. He would select the pen-point and the holder he wanted and begin to make circles in the air. Then, drawing towards him a gilt-edged place card or a crested one, on which menus were written, he would go to work. When he had finished, he arranged the cards all over the table to let them dry, and sat there at ease, only a step or two from Monsieur Victor’s desk, in a sector invaded by other waiters only when they were to be called down or to be discharged, waiters who came with nervous hands and frightened eyes to face Monsieur Victor. Mespoulets’s special talent guaranteed him his job and set him apart from the ordinary waiters. He was further distinguished by the fact that he was permitted to wear glasses, a privilege denied all other waiters, no matter how near-sighted or astigmatic.

It was said of Mespoulets variously that he was the father, the uncle, or the brother of Monsieur Victor. It was also said of him that he had once been the director of a lycée in Paris. The truth was that he had never known Monsieur Victor on the other side, and I do not think there was any secret between them, only an understanding, a subtle sympathy of some kind. I learned that he had once been a tutor to a family in which there was a very beautiful daughter and that this was something he did not like to talk about. He loved animals almost as dearly as he loved the French language. He had taken it upon himself to watch over the fish which were in an aquarium in the outer lobby of the hotel, he fed the pigeons in the courtyard, and he extended his interest to the birds and beasts and crustaceans that came alive to the kitchen. He begged the cooks to deal quickly, as painlessly as could be, with lobsters and terrapins. If a guest brought a dog to our section, Mespoulets was mostly under the table with the dog.

At mealtime, while we waited for the few guests who came our way, Mespoulets sat out in the linen-closet on a small box where he could keep an eye on our tables through the partly open door. He leaned comfortably against a pile of table-cloths and napkins. At his side was an ancient Grammaire Française, and while his hands were folded in his lap, the palms up, the thumbs cruising over them in small, silent circles, he made me repeat exercises, simple, compact, and easy to remember. He knew them all by heart, and soon I did, too. He made me go over and over them until my pronunciation was right. All of them were about animals. There were: ‘The Sage Salmon’, ‘The Cat and the Old Woman’, ‘The Society of Beavers’, ‘The Bear in the Swiss Mountains’, ‘The Intelligence of the Partridge’, ‘The Lion of Florence’, and ‘The Bird in the Cage’.

We started with ‘The Sage Salmon’ in January that year and were at the end of ‘The Bear in the Swiss Mountains’ when the summer garden opened in May. At that season business fell off for dinner, and all during the summer we were busy only at luncheon. Mespoulets had time to go home in the afternoons and he suggested that I continue studying there.

He lived in the house of a relative on West Twenty-fourth Street. On the sidewalk in front of the house next door stood a large wooden horse, painted red, the sign of a saddle-maker. Across the street was a place where horses were auctioned off, and up the block was an Italian poultry market with a picture of a chicken painted on its front. Hens and roosters crowded the market every morning.

Mespoulets occupied a room and bath on the second floor rear. The room was papered green and over an old couch hung a print of Van Gogh’s Bridge at Arles, which was not a common picture then. There were bookshelves, a desk covered with papers, and over the desk a large bird-cage hanging from the ceiling.

In this cage, shaded with a piece of the hotel’s billiard cloth, lived a miserable old canary. It was bald-headed, its eyes were like peppercorns, its feet were no longer able to cling to the roost, and it sat in the sand, in a corner, looking like a withered chrysanthemum that had been thrown away. On summer afternoons, near the bird, we studied ‘The Intelligence of the Partridge’ and ‘The Lion of Florence’.

Late in August, on a chilly day that seemed like fall, Mespoulets and I began ‘The Bird in the Cage’. The lesson was:

L’OISEAU EN CAGE

Voilà sur ma fenêtre un oiseau qui vient visiter le mien. Il a peur, il s’en va, et le pauvre prisonnier s’attriste, s’agite comme pour s’échapper. Je ferais comme lui, si j’étais à sa place, et cependant je le retiens. Vais-je lui ouvrir? Il irait voler, chanter, faire son nid; il serait heureux; mais je ne l’aurais plus, et je l’aime, et je veux l’avoir. Je le garde. Pauvre petit, tu seras toujours prisonnier; je jouis de toi aux dépens de ta liberté, je te plains, et je te garde. Voilà comme le plaisir l’emporte sur la justice.

I translated for him: ‘There’s a bird at my window, come to visit mine.… The poor prisoner is sad.… I would feel as he does, if I were in his place, yet I keep him.… Poor prisoner, I enjoy you at the cost of your liberty … pleasure before justice.”

Mespoulets looked up at the bird and said to me, ‘Find some adjective to use with “fenêtre”, “oiseau”, “liberté”, “plaisir”, and “justice”,’ and while I searched for them in our dictionary, he went to a shelf and took from it a cigar-box. There was one cigar in it. He took this out, wiped off the box with his handkerchief, and then went to a drawer and got a large penknife, which he opened. He felt the blade. Then he went to the cage, took the bird out, laid it on the closed cigar-box, and quickly cut off its head. One claw opened slowly and the bird and its head lay still.

Mespoulets washed his hands, rolled the box, the bird, and the knife into a newspaper, put it under his arm, and took his hat from a stand. We went out and walked up Eighth Avenue. At Thirty-fourth Street he stopped at a trash-can and put his bundle into it. ‘I don’t think he wanted to live any more,’ he said.

II

Art at the Hotel Splendide

‘From now on,’ lisped Monsieur Victor, as if he were pinning on me the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, ‘you will be a waiter.’

It was about a year after I had gone to work at the Splendide as Mespoulets’s bus boy, and only a month or two after I had been promoted to commis. A commis feels more self-satisfied than a bus boy and has a better life all around, but to become a waiter is to make a really worthwhile progress.

The cause of my promotion was a waiters’ mutiny. On a rainy afternoon several of the waiters had suddenly thrown down their napkins and aprons and walked out. One had punched the chief bus boy in the nose and another had upset a tray filled with Spode demitasse cups. They wanted ten dollars a week instead of six; they wanted to do away with certain penalties that were imposed on them, such as a fine of fifty cents for using a serving napkin to clean an ashtray; and they wanted a full day off instead of having to come back on their free day to serve dinner, which was the custom at the Splendide, as at most other New York hotels. The good waiters did not go on strike. A few idealists spoke too loudly and got fired, and a lot of bad waiters, who had mediocre stations, left.

After my promotion I was stationed at the far end of the room, on the ‘undesirables’’ balcony, and my two tables were next to Mespoulets’s.

It rained all that first day and all the next, and there were no guests on the bad balcony. With nothing to do, Mespoulets and I stood and looked at the ceiling, talked, or sat on overturned linen-baskets out in the pantry and yawned. I drew some pictures on my order-pad – small sketches of a pantryman, a row of glasses, a stack of silver trays, a bus boy counting napkins. Mespoulets had a rubber band, which, with two fingers of each hand, he stretched into various geometric shapes. He was impressed by my drawings.

The second night the dining-room was half full, but not a single guest sat at our tables. Mespoulets pulled at my serving napkin and whispered, ‘If I were you, if I had your talent, that is what I would do,’ and then he waved his napkin towards the centre of the room.

There a small group of the best guests of the Splendide sat at dinner. He waved his napkin at Table No. 18, where a man was sitting with a very beautiful woman. Mespoulets explained to me that this gentleman was a famous cartoonist, that he drew pictures of a big and a little man. The big man always hit the little man on the head. In this simple fashion the creator of those two figures made a lot of money.

We left our tables to go down and look at him. While I stood off to one side, Mespoulets circled around the table and cleaned the cartoonist’s ashtray so that he could see whether or not the lady’s jewellery was genuine. ‘Yes, that’s what I would do if I had your talent. Why do you want to be an actor? It’s almost as bad as being a waiter,’ he said when we returned to our station. We walked down again later on. This time Mespoulets spoke to the waiter who served Table No. 18, a Frenchman named Herriot, and asked what kind of guest the cartoonist was. Was he liberal?

‘Ah,’ said Herriot, ‘c’ui là? Ah, oui alors! C’est un très bon client, extrêmement généreux. C’est un gentleman par excellence.’ And in English he added, ‘He’s A-1, that one. If only they were all like him! Never looks at the bill, never complains – and so full of jokes! It is a pleasure to serve him. C’est un chic type.’

After the famous cartoonist got his change, Herriot stood by waiting for the tip, and Mespoulets cruised around the table. Herriot quickly snatched up the tip; both waiters examined it, and then Mespoulets climbed back to the balcony. ‘Magnifique,’ he said to me. ‘You are an idiot if you do not become a cartoonist. I am an old man—I have sixty years. All my children are dead, all except my daughter Mélanie, and for me it is too late for anything. I will always be a waiter. But you – you are young, you are a boy, you have talent. We shall see what can be done with it.’

Mespoulets investigated the famous cartoonist as if he were going to make him a loan or marry his daughter off to him. He interviewed chambermaids, telephone operators, and room waiters. ‘I hear the same thing from the rest of the hotel,’ he reported on the third rainy day. ‘He lives here at the hotel, he has a suite, he is married to a countess, he owns a Rolls-Royce. He gives wonderful parties, eats grouse out of season, drinks vintage champagne at ten in the morning. He spends half the year in Paris and has a place in the south of France. When the accounting department is stuck with a charge they’ve forgotten to put on somebody’s bill they just put it on his. He never looks at them.’

‘Break it up, break it up. Sh-h-h. Quiet,’ said Monsieur Maxim, the maître d’hôtel on our station.

Mespoulets and I retired into the pantry, where we could talk more freely.

‘It’s a very agreeable life, this cartoonist life,’ Mespoulets continued, stretching his rubber band. ‘I would never counsel you to be an actor or an artist-painter. But a cartoonist, that is different. Think what fun you can have. All you do is think of amusing things, make pictures with pen and ink, have a big man hit a little man on the head, and write a few words over it. And I know you can do this easily. You are made for it.’

That afternoon, between luncheon and dinner, we went out to find a place where cartooning was taught. As we marched along Madison Avenue, Mespoulets noticed a man walking in front of us. He had flat feet and he walked painfully, like a skier going uphill.

Mespoulets said ‘Pst,’ and the man turned around. They recognised each other and promptly said, ‘Ah, bonjour.’

‘You see?’ Mespoulets said to me when we had turned into a side street. ‘A waiter. A dog. Call “Pst,” click your tongue, snap your fingers, and they turn around even when they are out for a walk and say, “Yes sir, no sir, bonjour Monsieurdame.” Trained poodles! For God’s sakes, don’t stay a waiter! If you can’t be a cartoonist, be a street-cleaner, a dish-washer, anything. But don’t be an actor or a waiter. It’s the most awful occupation in the world. The abuse I have taken, the long hours, the smoke and dust in my lungs and eyes, and the complaints—ah, c’est la barbe, ce métier. My boy, profit by my experience. Take it very seriously, this cartooning.’

For months one does not meet anybody on the street with his neck in an aluminium-and-leather collar such as is worn in cases of ambulatory cervical fractures, and then in a single day one sees three of them. Or one hears Mount Chimborazo mentioned five times. This day was a flat-foot day. Mespoulets, like the waiter we met on Madison Avenue, had flat feet. And so did the teacher in the Andrea del Sarto Art Academy. Before this man had finished interviewing me, Mespoulets whispered in my ear, ‘Looks and talks like a waiter. Let’s get out of here.’

On our way back to the hotel we bought a book on cartooning, a drawing-board, pens and a pen-holder, and several soft pencils. On the first page of the book we read that before one could cartoon or make caricatures, one must be able to draw a face – a man, a woman – from nature. That was very simple, said Mespoulets. We had lots of time and the Splendide was filled with models. Two days later he bought another book on art and we visited the Metropolitan Museum. We bought all the newspapers that had comic strips. And the next week Mespoulets looked around, and everywhere among the guests he saw funny people. He continued to read to me from the book on how to become a cartoonist.