Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

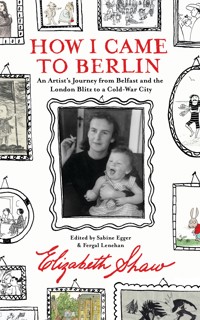

Elizabeth Shaw, who has until now remained all but unknown in her native Ireland, was one of the most celebrated children's authors in East Germany, producing a series of masterful children's books that have stayed in print since her death in 1992. She was also a deeply complex, passionate woman, a brilliant author, and a gifted artist beyond the confines of Children's literature. Born in Belfast in 1920 to Irish parents, Shaw was a life-long outsider, sheltered from the poverty and violence of the city at the liberal, left-wing Royal Academy. At the age of 12, her family moved to Bedford in England, and she would eventally go on to attend the Chelsea School of Art, impressing her teachers and absorbing the social and political struggles of her time. In 1939, she was called up to the war effort and worked in the London telephone exchange. Having published sketches in 1940 and contributed to the London left-wing magazines Our Time and Lilliput, she exhibited works in 1943 at the Artists' International Association in London. In 1944l, she met the Swiss-born émigré artist and communist René Graetz. They married in 1946 and, like other German exiles opposed to National Socialism, decided to help build a better, socialist Germany. Deeply inflected by the politics of East Germany, she worked as a caricaturist with Neues Deutschland, the newspaper of East Germany's ruling Socialist Unity Party, before going on to write 23 enromously successful books for children, making her a household name across Germany. By times elusive, moving and deeply revealing, this is a finely tuned memoir by one of Ireland's great forgotten artists - now illustrated with many never-before-published illustrations, and with an insightful and enligtening afterword by Fergal Lenehan and Sabine Egger which delves into the under-explored aspects of Shaw's relationship to Stalinism, the GDR, and those around her.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 286

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

How I Came to Berlin

How I Came to Berlin

An Artist’s Journey from Belfast and the London Blitz to a Cold-War City

Elizabeth Shaw

Foreword by Anne Schneider

Edited with an Afterword by Sabine Egger & Fergal Lenehan

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published in English 2025 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road,

Arbour Hill,

Dublin 7,

Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © The Estate of Elizabeth Shaw, 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 84351 952 2

eBook ISBN 978 1 84351 953 9

Set in 12 pt on 16.5 pt Adobe Jenson Pro and Adobe Caslon Pro by Compuscript

Cover design by Katie Tooke, katie-tooke.com

Printed and bound in Czechia by Finidr

CONTENTS

Foreword by Anne Schneider

How I Came to Berlin

Afterword by Sabine Egger and Fergal Lenehan

Endnotes

Index

FOREWORD

My parents are still very close to me and, as always, you only realize what has been left unsaid when they are no longer around. Some of the things they did I only understand now, some I still cannot comprehend. But I think that’s normal: parents live their own lives and children shouldn’t try to judge them in retrospect.

When our mother died in 1992, we, my brother Patrick and I, found in her will the wish that her ashes would be scattered in the Irish Sea so that they would reach the Atlantic Ocean when the wind was favourable. Everyone in the family agreed, but making it happen was quite complicated, at least as far as the ashes were concerned. The really nice thing about this, despite the sadness of the occasion, was that we went to Ireland for the first time and met an incredible number of relatives there who organized everything and finally found a place, Carlingford in County Louth, on whose pier we scattered the ashes into the Irish Sea. It was wonderful to hear the family stories. We were both over forty years old and had never seen the country from which our mother had come to Germany. We only really knew the stories about her relatives from England; her siblings had all stayed there and had families there. We saw them very rarely after the Wall was built in 1961; only a few ventured into East Berlin. The long period without direct contact with relatives in Ireland, England and Wales naturally had an impact on the intensity of the relationships, but I know for sure that if we decide to visit them, we will be warmly welcomed.

Until his death in 2006, my brother Patrick worked very intensively on our parents’ estate, maintaining contacts with publishers and organizing exhibitions. Now that I’m looking after the drawings and the books, I realize that I know very little about my mother’s life before 1946. There are drawings by her for the English monthly magazine Lilliput, illustrations, political caricatures and sketches. I tracked down a supplier in London on the Internet who still has old posters drawn by her in stock.

When they came to Berlin, our parents were twenty-six and thirty-eight years old respectively. They hadn’t yet made up their minds artistically, they were curious and willing to become involved in something new. That was certainly difficult and also beautiful, as it is with artists, an up and down that fosters creativity. For Patrick and me, the hallmarks of such an eventful artistic life were always a normal part of our childhood – listening to foreign languages, discussions late into the night, books everywhere, going to the cinema and theatre together, hiking and swimming, the Baltic Sea, stories about the family and, of course, drawing and painting.

To this day, I am always delighted by the watercolours and pencil and pen drawings by my mother that I find in the many sketch books and in the drawing cabinet. There are drawings of the apartment in Berlin’s Treskowstraße that complement the memories in my head. Drawing was obviously my mother’s way of intensively engaging with her surroundings. There are some books in German in which this can still be admired: Spiegelbilder [Mirror Images], Das dicke Elizabeth-Shaw-Buch [The Big Elizabeth Shaw Book] and Eine Feder am Meeresstrand [A Feather on the Seashore].

Better-known than these titles aimed at an adult audience are, of course, my mother’s children’s books. These still remain very present today: Kinderbuchverlag Berlin, the first port of call for beautifully designed books for a young audience in the former German Democratic Republic, is now part of the Beltz Publishing Group, and my mother’s books are available and still popular more than thirty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was more than sixty years ago in 1963 that Der kleine Angsthase [The Timid Rabbit] was first published, and it is my experience that people of all ages remember this book as part of their childhood or of their reading time with their own children.

Exhibitions of Elizabeth Shaw’s work have been held in all of the eastern German states. In 2010 we were lucky enough to be able to show the original drawings of some of her children’s books at Burg Wissem in Troisdorf near Cologne, a unique museum specializing in artistic picture-book illustration. It is perhaps also worth mentioning that there has been a primary school called after Elizabeth Shaw – the Elizabeth-Shaw-Grundschule – in Berlin-Pankow for many years. In addition, there are always small theatre groups that produce very original performances based on the stories from her children’s books.

In 2023 we gave the original drawings from the children’s books to the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin [The State Library of Berlin], and in 2024 the original drawings of the illustrated books for adults were given to the Deutsches Buch- und Schriftmuseum [German Museum of Books and Writing] at the German National Library in Leipzig.

All in all, it can be said that my mother’s work is anything but forgotten today in Germany. But what about How I Came to Berlin? The autobiography, first published by the Aufbau Verlag in 1990, has always appealed to me. Many people in Germany know Elizabeth Shaw’s children’s books but know hardly anything about her life. The problems of integration, arriving and living in a country that is completely different, whose people have had completely different experiences – all of this is very much a part of normality today. I often think about the concept of home – or Heimat in German – which I cannot really define for myself. Perhaps everything written in the memoir is this sense of home for me, the totality of my ancestors’ experiences. For this edition I had to scan the English-language text written on a typewriter and transferred it to the computer. I had to read everything very carefully, including the description of a ‘walk’ through London in 1940. How horrible that must have been, at night, without any light, without a soul on the street! My mother and her siblings had the experience of being recognized as foreigners by their accent and their choice of clothing when the family moved from Ireland to England. You have to cope with all of that and, if possible, turn it into a type of positive energy. My mum went to London on her own as soon as she finished school and started her career as an artist, perhaps helped by the experiences she had already had. I only realized some things when I read her memoir. I found images I remembered and also find myself in this text, for example in Lyme Regis, a southern English harbour town, where I was on holiday in 2008: only when I reread the book did I fully realize that my parents were already there, with me, in 1948.

I think my mother was happy with her life. She was successful in her work, had her family in Germany, lots of friends, and she was inquisitive and curious. She was able to contribute to society with her very own talents. My knowledge of my mother is expanding, and it is a pleasure to meet her again and again.

Anne Schneider

2025

I

1

I and Pangur Bán, my cat,

’Tis a like task we are at;

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

’Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

’Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

Translated from the Irish by Kuno Meyer

Author unknown, ninth century

The first question I have been frequently asked since I came to live in Germany is whether I am related to George Bernard Shaw. To answer this, I can only quote the famous G.B.S. himself, who did a little research on the subject of his forefathers. He wrote: ‘I have no trace in me of the commercially imported North Spanish strain which passes for aboriginal Irish: I am a typical Irishman of the Danish, Norman, Cromwellian, and (of course) Scotch invasions.’

This could apply to me too, except that G.B.S. belonged to the eastern Dublin Shaws, and I belong to the western Sligo Shaws, where some of that North Spanish strain was added by my grandmother McKim.

As you see the Irish are very conscious of clan and history.

The second question which I have been frequently asked since I came here is why did I come to Berlin. To answer this, I have to think a long way back.

I was born in a Protestant bed, delivered by a Catholic doctor. This was in 1920, in the middle of Belfast, when the ‘Troubles’, the sectarian violence, once again escalated in the city. It was advisable then to keep away from the windows because of stones aimed at them, or because of rifle shots from neighbouring rooftops. It was dangerous for a Catholic to be seen entering a Protestant house. We had a maid called Bridget, of whom I was very fond. She was a Catholic and one day a note was dropped through the letterbox saying that if we did not send her away, she would not be the only one to suffer. Such threats were to be taken seriously, and so one of my earliest memories is of sitting on my mother’s arm at the street door and being told to wave goodbye to Bridget, as she walked away with her suitcase. I realize now that this public farewell was staged for the benefit of unseen hostile observers.

We lived above the York Street branch of the Ulster Bank on the corner of Earl Street. The rooms were large and dusty with high, dirty windows, barred at the back of the house, some with stained glass, decorated in the style of the turn of the century. Opposite us towered the massive red-brick Gallaher’s Tobacco factory. Life was regulated by ‘Gallaher’s Horn’, the factory siren, which sounded in the morning, at midday and in the late afternoon. The air was pervaded with the odour of raw tobacco, stale beer and dust. Horse-drawn carts rattled from the docks to the station, and tall trams whined and clanged as they swayed past. Unease and poverty.

My father made hasty exits and entrances to and from the bank office on the ground floor. He swallowed his meals rapidly, retailing the events of the day, often stammering a little. Banks were not then so anonymous as they are today, and his attitude to the customers was paternalistic. ‘Old so-and-so was in today,’ I remember him saying, ‘and he wanted some money, but I told him he couldn’t have it, for he’d only spend it on drink!’

My father was always anxious to be finished with the office work so that he could do something which interested him. He was a self-educated man. No one could follow his method in arithmetical calculation, but the answer was always right. He had a wide range of interests and activities, but never in his life did he learn to boil an egg or darn a sock, for he was a man of the nineteenth century and such matters were taken care of by his mother, then his sister and then his wife. He had a daily programme with which he let nothing interfere. It began with dumbbell exercises, then off to the office to earn a living, then sport in the fresh air, before he settled down to read his many books. His native interest in the past had been sublimated into an interest in history generally and he pursued this with the detachment of a dedicated librarian. This fondness for reading influenced me at an early age and I still find the smell of a newly unfolded newspaper as enticing as the odour of fresh rolls is to some. Before breakfast my father put on his hat, took his walking stick and walked rapidly as usual to the small newspaper shop in York Street. He snatched a little fresh air and picked up his copy of the daily Northern Whig, as well as the weekly Punch and Illustrated London News, when they were due. There was no television and no radio in those days, and one read the papers to find out what was happening – according to the viewpoint of the paper, of course. I remember a drawing in the London News which depicted a monster rather like Jabberwocky in Alice in Wonderland, entitled A Bolshevik, and well calculated to raise a shudder.

There were no restrictions as to what we read in the extensive collection of my father’s books, which began with a faded pink paperback series of the Penny Poets and continued with the bestsellers of his youth, Maurice Jokai, Marie Bashkirtseff, an early paperback of Tolstoy and fat volumes of history, all signed, with the date of purchase, in spidery handwriting.

When the papers and magazines had been read, they were stacked in a small dark cupboard room, known as the Paper Pantry. There we used to rummage among old tracts of the abstinence movement – Grandfather Shaw had drunk too much – and shuddered at woodcuts depicting the fate of little girls driven bleeding out into the snow by an inebriated father. Our parents’ love letters were there, tied in bundles, and there were newspaper cuttings of my father’s shy attempts to take a course in writing fiction, offered by the Irish Times, and the rude reply to ‘G. Wash’ saying that he had no talent and might as well give up at once. In the Paper Pantry there were many secrets of which we never spoke, and our parents did not either, but they induced a kind of gentle understanding. We browsed too through stacks of illustrated magazines dating back to the 1890s. Reading about politics and history was very much a part of daily life in our high house, overlooking the shabby rooftops of dockland Belfast.

2

Because we lived in the midst of a dirty and dusty city and because we might have inherited a Shaw weakness of the lungs from which several relatives had died, we spent all our holidays in the country. Mostly we went to our maternal grandparents in the Magowan farmhouse among the bumpy green hills of County Armagh, the blue tip of Slieve Gullion in the Mourne Mountains always visible in the distance. The Magowan house on the outskirts of the village Mountnorris was built in neat eighteenth-century style. Behind the house was an older one, used for storage, and connected to the later building by the stone-flagged kitchen, which was the centre of the house. Once there had been an opening in the roof to let out smoke. From the kitchen a room had been built on, a small dining room, which opened on to the yard, with its stables, dairy and various outhouses. A house permeated with a long changing past and a paradoxical stability.

The Magowans had come over from Scotland and settled in Mountnorris some three centuries before. They came, it is said, looking for work, and became servitors of the O’Hanlon clan, to whom the land then belonged. Later they were joined by Presbyterian settlers from the lowlands of Scotland and French Huguenot refugees. They formed a close-knit community with much intermarriage. Many Scottish traditions were preserved, including an emphasis on the importance of education and a fierce independence. Nonconformism was particularly manifest among the Irvines, my grandmother’s family – her eldest brother being perhaps an exception, as he became a professor of theology at Magee University. A second brother became a doctor, practised abroad, then returned to his native village. He wrote books about medicine and social progress, in which he quoted extensively George Bernard Shaw, condemning the trade in patent medicines. He preached tolerance in religion as well and put his principles into practice by marrying a Catholic midwife from Cork.

We used to watch our great-aunt Mary, dressed in ancient silk dresses and a toque styled around 1880, walking down the hill to the Catholic chapel to attend Mass on Sunday, while Granny in her best black hat set out in the opposite direction to the Presbyterian Meeting House. We did not join her because we belonged to the Church of Ireland, Protestant too, but the congregation knelt to pray and sang hymns almost Popish, said Granny. Uncle Gilbert, the doctor, did not go to any church, but smoked a big cigar at home, which yellowed his white moustache, and tilted his straw hat over a sardonic eye as he viewed the scene.

Uncle Gilbert’s eccentricities were accepted by his understanding siblings, for they had been brought up in a harsh Calvinist tradition: family were not allowed to learn a profession, they were all expected to marry and raise families. My granny, the eldest, transferred her frustrated ambition to her children. They should all study, get scholarships, get on in life – the girls too!

Elizabeth Shaw’s grandmother, Sarah Ann Magowan, circa 1936.

The Irvines were small and wiry, energetic and tough. The Magowans were emotional and often darkly depressive. Those of her nine children who took after the Magowans had a rough time with Granny. However, aided by the village schoolmaster, Mr Morrison, most of them went her way. The eldest was her special pride, as he became a diplomat and was even knighted. The two eldest girls won scholarships to Trinity College in Dublin, and the younger boys went in for medicine and veterinary surgery.

Trinity College Dublin, 1916. Front row, first from left: Elizabeth‘s mother Mary Magowan, third from left: her sister and godmother of Elizabeth, Jane Elizabeth Magowan.

Our grandfather, whom we called Papa, like our very young uncles and aunts did, used to pick us up with horse and trap at Goraghwood Station,1 which we reached by train from Belfast. The train had no corridor in those days, and the compartments were locked and unlocked at each station. We all climbed into the swaying trap, and it was great to be allowed to sit in front with Papa and hold the reins. During the day Papa was mostly outside, working on the farm. In the evening he would come into the kitchen with the horse collars and harness and hang them on the wall. Then the wicks of the oil lamps were trimmed and lit, first burning with a low flame, then turned up high to a soft glow. A time came when Papa was ill and there he was, sitting up in bed in a white nightshirt, smiling kindly when we came to visit, but we knew it was a sickbed visit, and I was frightened.

Then he died, and I thought I heard his ghost walking in the attic. In front of the house was an enormous, very old beech tree. Its rustling leaves were the music of the night, and one of the girls who worked in the house told me that once when she returned in the evening, she saw a banshee in the tree, looking down at her. One day I went out of the house and there was an old man with a white beard sitting on the milk churn standing under the beech tree smiling kindly. I thought for a moment it was Papa’s ghost and nearly fainted.

‘Don’t bring white hawthorn into the house, it brings bad luck!’ ‘Never open an umbrella in the house!’ for the same reason, and if you should be unlucky enough to spill some salt, a pinch thrown over the left shoulder with the right hand will undo the evil spell.

There was quite a social life in the stone-flagged kitchen. Granny was the central figure, dressed in black, small, brisk and sharp, churning butter in the big wooden hand churn, out to feed the hens, ‘Birdie, birdie, birdie!’ – cooking porridge and chicken soup, calling the men on the farm to dinner on the washed wooden kitchen table. Meals consisted of potatoes, home-made bread, salty butter, bacon, porridge, eggs, oatcakes, beans, cabbage and chicken. All produce of the farm, except tea and sugar, which were bought at Joe Hare the grocer down the bog road.

We had a glimpse of living history here, of a lifestyle which had hardly changed in three hundred years or more. Later when the boys were earning well, electricity was installed in the house, running water replaced the pump in the yard, and a bathroom and toilet were built. A little Austin minicar replaced the horse and trap, and young uncle Irvine, the veterinary surgeon, introduced fancy experiments in the byre – the cowshed – installing water taps with levers, which the cows could push with their noses themselves and drink when thirsty.

Down the hill, towards the Chapel Road, sometimes we met in winter poor children carrying big bundles of firewood on their backs, which they had gathered from the hedges. They had bare blue feet and running noses.

‘It’s a brave day!’ they greeted politely.

‘Brave day!’ we replied.

In the country poverty was painful too.

In spite of the success of her children in their various careers, and the opportunities they offered her to visit them in far-flung places, Granny never went more than fifty miles from the village in her long life – because of the hens, she said. She rose every day at six and cooked her oatmeal porridge. When the lamps were lit in the evening, she did the crossword puzzle in the newspaper, with the help of all present in the kitchen, or read a book before going to bed at nine. Sometimes we slept in another bed in her room, and then I watched with half-shut eyes as she undid her knot of hair and a long grey pigtail fell down her back. Then she took off her dress and her knee-length frilled cotton knickers, put on a long white nightdress and got into bed, blowing out the candle by her bedside.

3

Granny killed chickens by wringing their necks. At the other farmhouse in Belcoo,1 in the west of Ireland, where we often stayed, our cousin Maud chopped their heads off with an axe. Maud and Kathleen Tate were relations on our father’s side of the family, and life was quite different there to life at Granny’s in Mountnorris.

The Tate sisters were cousins of ours. When their mother died Kathleen was adopted by our Shaw grandmother, who lived with my father in Belfast until her death in 1912. Maud kept house for her father, Dr Tate, in Belcoo, and when my father married, Kathleen came to live with her. Maud was tall and red-haired, big teeth, jolly laugh. She ran the farm. Kathleen, frail, slight and pale, drifted about, cooking little scones and turning out meals at unexpected intervals, giggling quite a lot in a friendly way. Both were unmarried. It was leisurely in Belcoo. Time did not seem to matter. No Magowan ambitions were pursued. I cannot remember seeing books in the house, but there was a small glass veranda above the front door where a pile of old magazines lay among pots of geraniums, where we liked to sit in the warm sunshine, reading and enjoying the strange odour of the plants. Maud and Kathleen must have gone to school somewhere, but they never mentioned it. The spirit of Mr Morrison, the village schoolmaster in Mountnorris, was far away. There was a piano in the living room, and an oil painting by Jack Yeats, brother of the poet William Butler Yeats, hung on the wall. They were neighbours.

‘But whatever happened to poor Willie?’ mused Maud.

People dropped past – a curate who played the piano and sang, armed customs guards from the frontier down the road, and there was much talk and laughter. The sisters lived in a house called Danesfort, among fine wild scenery of mountains and lakes. Sometimes we went fishing on the lake with Maud. A stream ran along the bottom of the garden, where trout swam in small deep pools and coloured dragonflies darted over the water. There was a short drive up to the house, lined with fir trees and a stretch of meadow at the side. On this there was a hillock with a few trees on top, and inside these was a ring of stones, the grave of some old Danes, who had invaded the coast here around the ninth century and given the house its name. The grave had been examined by archaeologists but then left undisturbed, because otherwise, it was said, it would bring bad luck.

A little along the road was the quiet lake, Upper Loch Macnean, on the left, and moorland on the right. At the crossroads there was a small pool known as the Wishing Well, a circle of moss-covered stones surrounding a spring of delicious clear water, from which we used to drink with hollowed hands, and then walk round the well and make a wish, which should come true.

Opposite Danesfort lived old Mrs Doherty, in a tiny, white-washed cottage with a thatched roof. When Kathleen had baked some fresh scones, we were told to take a few over to Mrs Doherty. She was very poor. Hens wandered in and out of the cottage, roosting on the beams, and when we asked if we could scatter some grain for them, Mrs. Doherty said yes, but then ‘Not too much!’ Once she showed us a present she had received, a lump of fat bacon, wrapped carefully in a cloth, like a precious stone. We travelled from Belfast to Belcoo by train. In Enniskillen we changed to a small old-fashioned train, which we sarcastically called ‘The Belcoo Express’. The train took off when it suited the railway staff, rather like Kathleen’s cooking habits. When it was time for us to return to Belfast, Maud waited until she heard the engine whistle, and then she went down to the field to catch the pony, which was to transport our luggage to the station.

Today this all sounds very idyllic. For us from the city, with its social tensions, with its dirt and noise, it was indeed.

Was it really such an intact world?

I would say, yes.

The frightful poverty, the damp climate, which encouraged tubercular disease, drove people away, but the water was pure, the air unpolluted, there were no old plastic bags on the shore of the lake, and scarcely a car on the rough roads.

4

Most summers we visited our Aunt Annie. She was my father’s sister. As she was a widow, she lived for a time with him in Belfast, and when he married, he bought her a house on the north coast, in the seaside resort of Portstewart, so that she could support herself and her daughter by running a boarding house for holidaymakers. We did not like staying there because the house smelt of cabbage and burnt cake, the unsuccessful result of Cousin Peggy’s cookery course. We did not like Aunt Annie or her daughter, who complained continuously, and as soon as we could we set off on expeditions with sandwiches and bathing suits. We walked along the promenade, past the small harbour. When the tide was in, each wave threw up a jet of water through a hole in the rocks. We followed a cliff path, crossed a small shell-strewn beach and came at last to the wide, white strand, washed by the strong waves of the Atlantic. In the background rose high sand hills and, in the distance, one could see the blue mountains of Donegal. Sometimes in the evening we went out over the stretch of grass and sea-pinks at the back of the house to the rocks beyond, clear pools between them when the tide was out, where velvety sea anemones waved, and tiny sea creatures darted to and fro. There too we could watch dramatic scarlet sunsets over the western water.

How lucky we were to have relatives so well-placed and willing to receive a family with four children!

The Shaw family in Portstewart, 1933. From left to right: Elizabeth, sister Matilda, mother Mary Shaw, father George W. Shaw, brothers Patrick and Warren (in front).

5

The Shaws probably came over to Ireland in the seventeenth century, as adventurers, as Cromwellian soldiers, in the English army of occupation. They received grants of land as a reward for their services. They belonged to what was known as the Protestant Ascendancy, the dominant influence in social life. They considered themselves a cut above the Magowans, who were tenant farmers. The Shaws and their kin raised horses which lost races, went salmon fishing and drank the good whiskey. When money was short, they managed to get another grant of land, as long as that was possible, or emigrated to the colonies.

Elizabeth’s grandfather George William Shaw, circa 1902.

Grandfather Shaw died in 1888, leaving debts and a widow with six children, the eldest being my eighteen-year-old father. After a vain attempt to run the estate most of it was sold, and he took a job as a clerk in the Ulster Bank in Ballina. He worked hard for a small wage, sent most of it home to his mother and cured himself of threatened tuberculosis by taking long walks over the mountains. Finally, he was appointed manager of the Ulster Bank in York Street, Belfast. There were spacious, rent-free living quarters over the bank, and he moved in with his mother, his widowed sister and her daughter and Kathleen Tate. So the female members of the family were taken care of. The younger brothers dispersed, emigrated to New Zealand, or died of tuberculosis. One settled in Dublin and founded a family of staunch republicans down there. My mother, then Mary Magowan, studied languages at Trinity College in Dublin, and during vacations she used to work as assistant teacher in her old boarding school in Whitehead, not far from Belfast. The headmistress of the school, Miss McKeowan, had an eye on my father as an eligible bachelor and a good match for one of her girls, and she used to send them as messengers to consult him on bank business. With Mary she had success at last. My mother broke off her studies at Trinity College, much to the chagrin of teachers and feminist friends, for she was doing well. But the difference in age was great – almost thirty years – and she felt that she should not wait. They married in 1918, and the widowed sister and Kathleen Tate were hustled out to make way for the bride.

River estuary in Ballina, Ireland, 1982.

1

6

Once when my little brother was about six, he was riding his tricycle along the street in front of our house in Belfast when he was accosted by a bigger boy, who blocked his path and demanded belligerently: ‘What sort of man are you?’ My little brother hesitated. He knew that the wrong answer could cost him a bloody nose. ‘I’m a Christian!’ he said, at last. ‘Then get away from a good Protestant like me!’ growled the big boy, taken aback. My little brother pedalled away hastily to the fortress of our house, the Ulster Bank.

As banks are, it was solidly built of red brick and stucco, with a marble base. Iron gates closed over the front and side entrances, all the back windows were barred, a pistol in a case lined with blue velvet lay on the dressing table of the guest room – it was loaded, we were warned – and a policeman stood day and night on duty at the corner. At the back of the house the cranes of the docks could be seen rising in the distance beyond a sea of rooftops, between which, from time to time, the funnels of a steamer moved out to Belfast Lough with a weary moan. From York Street, as it was then, cobbled side streets branched out with rows of small brick houses, built about the middle of the nineteenth century. They had names like Earl Street and Queen Street, but here lived no earls and queens, only the wretched and filthy poor. There were Protestant streets and Catholic streets distinguishable by their graffiti. Protestant walls were decorated with large, coloured murals of King William of Orange on a white horse, winning the Battle of the Boyne against Catholic James I. ‘Remember 1690!’ was the slogan and sometimes, rudely, ‘Kick the Pope!’ The Catholics retorted with a reminder of the Easter Uprising in Dublin, ‘Remember 1916!’ and ‘Up Dev!’ De Valera was then president of the Republic.1