10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

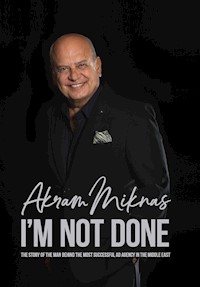

The name 'Akram Miknas' is synonymous with the birth and growth of the advertising industry in the Middle East. He embodied the styles of David Ogilvy and Leo Burnett with a flair all his own, and his vision of the industry was far more sophisticated than that of any of his contemporaries. Miknas founded Fortune Promoseven (FP7), now the largest advertising and communications agency in the region, with six friends and $7,000 in Beirut, Lebanon in 1968. His passion, creativity and persistence have driven a perpetual winning streak: he refuses to fail. His charisma, charm and vision have helped him win clients and friends all over the world. I'm Not Done is the moving story of a perennial achiever, told in his own unique voice – warm, intimate and charming. It is also a glimpse into an age of discovery in a region that needed dreamers, told by the brand man who marketed it all.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

I’m Not Done

The Story of the Man Behind the Most Successful Ad Agency in the Middle East

Akram Miknas

I’m Not Done

The Story of the Man Behind the Most Successful Ad Agency in the Middle East

Published by

Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court

South Street

Reading

RG1 4QS

UK

www.garnetpublishing.co.uk

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Copyright © Akram Miknas, 2019

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

First Edition 2019

ISBN: 9781859644553

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by: Samantha Barden

Cover image: Photographer: Loredana Mantello/Designer: FP7

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press:

Contents

Introduction

Prologue

Part One: Learning

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two: Making My Way

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Three: Dubai to Bahrain

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Part Four: Pitches and Growth

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Part Five: Expansion

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Epilogue

Introduction

Over the past few years, I have come to the decision that I need to tell my family and friends, and the people I have worked with, about my advertising journey. I think that my personal history is a reflection of the changes that have taken place in the Middle East in the business of communications and advertising. I believe that in some small measure I have had an impact on this history, as I have been an integral part of the process of evolution.

Prologue

‘God help you! God help you! Only God can help you now!’

More than forty-five years have passed and the housekeeper’s high-pitched screams still ring in my ears as if it were only yesterday. She was beating her breast and wringing her hands as she wailed. I just stood and stared at the screeching woman across the bed on which lay my mother, still trying to hold on to her life with all her strength.

I ran closer to the bed; all I saw was her angelic face, which is still engraved deep inside me. She beckoned me with her hands. I ran towards her crying out, ‘Don’t leave, don’t leave, Mama, Mama, don’t leave us!’ I was hysterical and yet the tears were frozen in my eyes. As I watched her life slip away I felt that she took with her everything that was beautiful in life. For me, at that moment, the world was strange; it was already lost.

Suddenly, all I wanted to do was to get away from the place, that dreaded room in which she’d spent her last few months. That house, which had never quite been a home for me, was the home of my stepfather, Khalil. The only love I had ever experienced there was that which my mother had lavished on me. I felt as though the walls were closing in. Everything around me felt dark and unfeeling. And through it all, like a jagged flash of lightning heralding an impending storm: the housekeeper’s screams.

‘Come and look at her!’ she yelled at me. ‘Come!’ she beckoned through her weeping and tears. Her howling filled the house, piercing my skull and ringing in my brain. It’s a sound that sometimes still echoes in my ears with all its original intensity and, if I pause to think about it, I am plunged into that terrifying moment as if it were yesterday.

I turned away and ran. I knew that my mother was gone forever, but I didn’t have the strength to approach her lifeless body. For several months I had known – we all knew – that she didn’t have much time left. Yet, that day, the reality of it caught me like an unexpected blow in the chest. The sobs rose like bile in my throat, but somehow I managed to control them and run, out of the house, away from the chaos around me.

I escaped to the woods behind our summer home in Aley near Beirut. I could only think of one thing: my sisters. ‘Oh, God! Baria and Amal,’ I said aloud to the woods and the sky. ‘They’re alone now; what can I do to help them? I am responsible for them now. It has happened. This dreaded day. Mama had asked me to prepare for it, but I’m not prepared, I’m not!’ I forced myself to control my tears and tried to concentrate on Mama’s last wishes: for me to care for my stepbrother and sisters. I told myself, ‘I must be strong. Mama asked me to be there for Jihad and Nawfal as well. What am I going to be able to do for all of them? It’s a big responsibility. I must carry it. I promised Mama! How can I help them? Dear God, how can I help anyone!’ On the day that my mother died that’s all I could think of – that and the housekeeper’s screams still reverberating in my head: ‘God help you! Only God can help you now!’

I kicked at the earth underfoot and threw stones at the trees. I thought of my mother and all that she had done for me and for others. She was always helping people. She ran a school for children in Burj al-Barajneh; she had even planned for my future. With a bitter laugh, I remembered that she’d just had a new suit made for me. I thought: she won’t see me wearing that! And yet she had always said to me, ‘Look smart. Be well-mannered, get a good education, go to university.’ At that moment I didn’t realise it, but this last plea from Mama was soon to become a mission for me.

At that moment my mind was all over the place. One minute I was recalling her words to me, the next I was thinking about Baria and Amal. Then I remembered that Mama had some land that she had given me. I remember wondering how much money I’d get if I sold it. Then I looked up at the sky and saw a plane flying; I thought, maybe I can become a pilot.

As all these possibilities played out I gradually calmed down. In my heart I knew I could do it. I could become a pilot if I decided to. In fact, I suddenly felt that I could be something more than a pilot – I could become whatever I wanted to be. With that small glimmer of hope, I returned home.

My mother had taught me to defy barriers. She said to me that there was no wall bigger than the Great Wall of China, but even this wall has entrances. This became the motivation for my life. Throughout my life I have never thought that I faced barriers to self-realisation. The word ‘no’ does not exist in my dictionary. I always look at it as: how can I do it and get what I want?

Part One: Learning

Chapter One

On 1 August 1961, Hekmat Abdul Hai Murad, my mother, died.

She was a great lady. Her father had been the Chief Judge of Jordan; her mother, the daughter of Yusuf Pasha al-Hassan, a member of the village of Batoratij – the last appointment made by the Ottoman Empire in Lebanon.

She was one of few women to gain a high education in Lebanon, and was able to persuade the Ministry of Education to open a girls’ school in one of Beirut’s poorest districts, Burj al-Barajneh. Within four years, this school became one of the largest in Beirut. All the students and staff loved her; she always urged me to mingle with them, and treat them as sisters.

I recall what she once said to me, ‘Do not accept failure. If you fail, quickly try again; again, a second, third and fourth time if necessary.’ She told me the story of Alexander of Macedonia who stood on the walls of Tyre after failing several times to break into it. He watched an ant on a tree as it tried to climb and fell, but tried again and again, and eventually reached the top. Then Alexander said to himself: is this ant better than me? Stories like this have sustained me through my life.

I had been the light of her life, her pet and her beloved son. I was mischievous, and had been thrown out of a number of schools; and I had been in and out of all kinds of scrapes. Yet she lavished all her affection and love on me. No one ever loved me as unconditionally, as purely, and selflessly, as she had. She wanted nothing but the best for me. I attended several schools, including the Choueifat, one of Lebanon’s oldest private schools, before my mother enrolled me, at the age of thirteen, in the International College of the American University. To this day it is one of the best schools in Lebanon, the Arab world and the region as a whole. It was an important move in my life – as if my mother was reassuring me, before her death, to stay in a prestigious school. I think she knew that this school would play a decisive role in my self-realisation, in giving me creative goals and high values.

In the summer sunshine on the day of her funeral, I stood up to talk about her. I don’t remember the words I said. I had pushed my sorrow and tears down into a space in my mind and shut them out. All I felt deep down was a heaviness in my heart and an ache that after all these years has still not left me. I wanted to be a man and felt that God wanted me to be one too, so I stood firm despite the deep sadness in me. For some inexplicable reason, I felt that I was responsible for her death. To my still immature mind, the fact that I could not have been blamed for the breast cancer that took her didn’t come into play. I looked at all the people around the grave, many of whom she had helped, and at that moment I felt that they too were all responsible for her death.

When I finished speaking, I looked at the crowd of people gathered to pay their respects to my mother. My heart leapt. There among the mourners, with a hand on each of my sisters’ shoulders, was my father, Rashad Miknas. At this moment I felt his paternal tenderness, and was convinced that he would do what he could for us. The fear of total abandonment was, in that instant, relieved, and a quiet sense of peace filled my heart.

I stepped down to join the mourners and let another speaker take my place. Just as I was beginning to feel a little calmer, behind me I heard my stepfather whisper loudly to someone, ‘Poor boy, he is finished.’ To this day I don’t know if it was said in malice or if he really felt I was done for. At that time, I felt he wanted me to hear him, and my whole being recoiled as if I had been slapped.

I turned around to look at him. My stepfather, Khalil, was a tall man with a hooked nose, a high forehead, receding hair, and large brown eyes. His lips were turned down in contempt of me and my condition. I saw no sympathy – not even the slightest hint of tenderness towards the son of the woman this man was supposed to have loved. He obviously envied my mother’s love for me.

In that instant, I decided, I was not finished. I had just started. This feeling settled on me with rock-hard resolve. Since then and throughout my life, whenever I face any difficulty, I remind myself that, ‘I am not finished.’

***

After the burial service and ceremonies, I rushed to my father’s side. He embraced us all, my sisters, Baria and Amal, and me.

My sisters were crying, ‘What will become of us? Where will we go?’

My father comforted us. ‘Don’t be afraid, Akram, I know your fears, I will not leave you or your sisters,’ he said. ‘You will come and stay with me.’

He turned and walked up to my stepfather and the other older people in the household to inform them that he would now be taking care of us.

While the older people were talking, my sisters clung to me, finally breaking down completely, their tears and sobs flowing.

‘Even if we stay with him, what will become of us?’ Baria asked. She was desperate and lost, and my heart went out to her.

‘We won’t have Mama any more,’ Amal added, weeping openly.

There they were, two young girls adrift and in need of an anchor. Their tear-stained faces were red from crying. I had to give them hope, although right then I had no plans and no hope myself. I put my arms around them. ‘Why are you worried? Dad is here, he is going to look after us, and I will always be there to support you.’

‘How?’ Baria, begged, ever the practical one.

‘What can you do?’ Amal chimed in. Although she was the elder of the sisters, she was shy, scared and easily discouraged.

‘We will think of something. I am a man. I will educate myself, I will work. I will do whatever it takes. I am your brother. Never forget that. Even when you have no one in this world, you will always have me.’

They both held on to me even tighter. Words cannot even begin to explain what we read in each others’ eyes and the feeling of that embrace. And so we stood for an instant, our arms around each other, three children between sixteen and nine years old preparing to take on whatever the future had in store for us.

Jihad and Nawfal, my half-brother and half-sister from my mother and stepfather, stayed with their father and I saw very little of them until we were all much older. My sisters and I went back to our father’s home in Tripoli, Lebanon. He was a jeweller and reasonably well-to-do with a comfortable life; but he’d married often and had many children, so there wasn’t that much to go around.

After the burial, we all returned with my father to his home in Tripoli, where I had been born on 29 May 1944 and where I had lived for six years before my parents separated. When they separated, my mother decided to live in Beirut, with me and my sisters, in Burj al-Barajneh.Growing up with my mother, we three children had the privilege of the affection and protectiveness of a virtuous mother who was generous and ambitious. She was a fighter and a believer in permanent work and activity. Her humanity, love and passion for culture and science had a tremendous impact on our upbringing. She knew exactly how to build her future and the future of her family, society and country.

After she died we went with my father to live in his large penthouse in a building that he owned, set on a hill, overlooking the Abou Ali river in the Abou Samra area of Tripoli. This time we were not there for a holiday, but for good. There was a well-kept garden in front, but the area behind was unkempt and overgrown with weeds and wild plants. It was like a small wood. There were days when I would escape to this place and for a few hours pretend that I was a young boy again. I’d climb trees, listen to the birds, run around and just be free. Sometimes, to ease my agitation, I would throw stones at trees, into the distance, anywhere. This had a calming effect on me. There are times, to this day, that I still resort to it when I’m deep in thought. It was a period in my life when the realisation that I needed to do something, anything, to take care of my sisters had set in motion a restlessness that has stayed with me since then.

***

For a brief while that fear of being left stranded and abandoned was held at bay; my father showered me with kindness and love when we first started living with him again. He was sorry for me and the only way he knew to express it was by hugging me or drawing me close, putting his hand on my shoulder – simple acts of sharing my pain without saying anything.

We spent a few weeks with my father while his wife, who was twenty-five years old, was on holiday with her children at her family home in Homs, Syria. So for those few weeks we had our father all to ourselves. We were able to bond, talk and reconnect with him. I discovered that the man I called my father, Rashad Ahmad Miknas, was a warm person, not highly educated, but nonetheless wise, successful and with a heart of gold.

About a week after our return, my father called me into the living room. His face was deeply serious. He was a handsome man of medium height, with sharp features, arresting eyes, and a charming smile, which he used generously. He was a self-made man and had struck out into the jewellery business after breaking away from his father’s business, which was running a Turkish bath in the jewellery souk in Tripoli. Although his education was very basic, he was intelligent and had even taught himself a little English. As far as the jewellery business was concerned, he was completely self-taught. His smile and his good looks made him a success. And he did well by it.

However, there were no smiles for me that day. ‘Sit down, we need to discuss your future,’ he said, nodding at the chair next to the sofa on which he was sitting. He absent-mindedly twirled the prayer beads that he often held in his hands.

I was nervous but sat down without showing any sign of my inner trembling. ‘Yes, Dad.’ I leaned forward to listen to him.

‘What do you want to do with your life?’

‘I’ll think of something. I mean I am now responsible for Baria and Amal, not just myself.’

‘Don’t worry about them, son. First take care of yourself. I will look after them and their education. It’s you I’m concerned about.’

‘Where will they go to school?’ I whispered, hoping that he would put them in a good school.

‘Here, in Tripoli’ he responded, ‘I’ll enrol them in the American School. They’ll be in boarding so they’ll be OK. And they’ll be home on the weekends.’

Those words put me at ease. I took a deep breath. ‘I want to be a pilot,’ I told him in earnest.

‘You can’t just become a pilot,’ he informed me, ‘You are too young, there are a lot of studies that you need to complete.’

‘I know,’ I said, ‘I do want to study and do well.’ I was aware of the fact that I couldn’t just leap into the profession.

‘That’s good.’ He nodded. ‘It will be good if you join me in the jewellery business. I see you as a personable young man and I think you’ll do well.’

‘I’ll think about it,’ I replied, ‘but Mama told me many times that I should go to AUB [American University of Beirut] and I want to go, not only to fulfil her wishes but to achieve something.’

He didn’t say anything. I think the idea made him uncomfortable. He knew that my mother was one of the few women in her generation who had been to university, and was among the first women to graduate from the University of Baghdad. Education was very important to her, always had been, but my father didn’t consider it that important.

Back in August 1961, I could never have imagined the life that eventually played out for me. As far as my sisters were concerned, my father did take care of them as he had promised. That immediate burden was temporarily lifted from my shoulders. Although my mother was a very strong woman, I grew up in a culture that believed and still believes that girls are fragile and need to be looked after, and that was my father’s thinking too. That summer, he secured their admission into the American School in Tripoli as he said he would. I was left to manage on my own. The world seemed a bleak and lonely place and the only comfort came from my father.

As soon as his wife returned from her holiday, she took one look at me and I could feel the venom in her eyes. ‘What are they doing here?’ she demanded of my father.

‘Their mother just died,’ he explained, challenging her with a look. ‘They’re my children and I’m all they have.’

She bit her tongue at that time and held back. But I had seen the pure hatred in her. She tried to hide it, but it came out in fits and spurts.

‘You’re spoiling him,’ she said to my father one day as he continued to pay a lot of attention to me and even hugged and caressed me in front of her.

He was firm. ‘Leave him alone. The poor boy has just lost his mother.’

She glared at me. Her eyes drilled their animosity into my head. I ignored her; I knew she envied his affection for me.

More than a sullen resentment, I could feel that there was real jealousy in her, the kind that steals people’s souls away. Some people have such a strong sense of self-preservation that their humanity leaves them. Any thought that I was just a teenager, with enough emotional problems to deal with at the best of times, that I was alone and perhaps lonely, didn’t cross her mind. She resolved to get rid of me.

She saw us as snobby city kids, smarter than her own children. She had that small-town suspicion of city people, and obviously hated the fact that my mother had been a well-educated, elegant and respected woman. Rashad’s wife was from Homs in Syria, married to a man who was her senior and had children from three previous marriages.

When my father wasn’t around she said nasty things to me, such as, ‘Because of you, your mother died.’ I said nothing. I kept quiet, gritted my teeth and concentrated on reading the schoolbooks that I had brought with me. I would run away to the open space behind the house. I’d kick the trees or throw stones with all the force I could muster. I had a burning rage inside of me and against the world. I fought with myself. ‘I will not cry. I will not cry,’ I promised myself.

***

‘She hates you, more than us,’ Amal said one day when we’d all gone to the woods, which was a refuge for us, away from her.

‘I don’t know why,’ I replied. ‘It’s not as though I’ve said or done anything to her. She’s just mean. Sometimes I think of running away.’

‘What about us?’ they both chimed in. ‘Don’t leave, Akram… don’t leave us, please don’t leave us!’

‘What will we do without you?’ Baria demanded. ‘You said you’d be there for us and here we are with the first bit of trouble and you’re ready to run!’ Her fear made her angry.

‘Don’t say that!’ I shouted at her. ‘I told you I will care for you and I will.’ I paced around in the woods. After a few seconds I forced myself to smile. ‘Look, I’m telling you, I will not abandon you. Dad is there for you. That woman doesn’t seem to hate you as much as she hates me. I want you both to remember that I’ll always be there for you. But you have to learn to be strong, too. I may not always be physically present. All I know is, first I must get myself on track and then I will be able to take care of you. OK, Baria.’ I grabbed her by the shoulders and forced her to look at me. ‘We have to support each other. Amal, you need to look out for Baria, and you, Baria, you have to listen to her. There will be times when it might seem as though I have forgotten you. In fact I’m sure there will be days when you’ll think that I have left you. But you both will always be here!’ I thumped my chest.

‘Why are you saying this?’ Baria exclaimed, fear making her eyes grow large.

‘I don’t know.’ I shook my head. ‘There are days when I feel I can’t take this any longer. But I do know that the most important thing for me is to get a good education, no matter what.’ Perhaps I had a premonition of events to come. It was one of those days when the determination and anger inside of me boiled up.

‘Dad will look after us, Akram is right,’ Amal said, trying to look on the bright side. ‘I know that he will. Look, he’s already got us admission to the American School and he bought us new dresses. He loves us. He really loves us.’

‘I do, too,’ I said, hugging them. ‘I want you to remember, no matter what happens, I will never let either one of you down. Promise me that you will remember this.’

‘We promise,’ they said, their faces sombre.

Although Baria was younger, she was the stronger of the two and I could see a firm resolve settle into her eyes. She was a determined girl. I looked at Amal; she was still so delicate. We hugged each other fiercely – not saying anything more, just fighting the emotions that were threatening to break our dams of resolve.

***

One morning, a few days later, my father’s wife offered me some food. I was surprised and thought perhaps she’d had a change of heart, so I suspected nothing. I took it to our room, where we usually had our breakfast. We three were given a room slightly detached from the rest of the apartment. It had a common bathroom just outside. And, once my father left for his work, we were expected to stay there and not interact with the rest of the family. Baria was with me and had also been given a similar bowl; I don’t recall where Amal had gone off to.

Not suspecting anything, I ate a few mouthfuls. A terrible fiery pain and the feeling of grit in my mouth made me spit out the food. Baria, who had taken just a spoonful, spat her morsel out immediately. There I saw it – pieces of broken glass and freshly flowing blood. I rushed into the bathroom with Baria at my heels. I vomited and saw more glass pieces. I spat and spat. Rinsed my mouth with cold water. Then she leaned over the sink and I made her spit out the glass too and wash her mouth.

Fortunately Baria hadn’t taken anything in. I vomited a few more times. I might even have swallowed some glass, I don’t know. This woman was so far gone that she was prepared to kill me. I banged the door, shouted at Baria, ‘Go! Just leave me alone!’ I burst out. I didn’t want her to see me as I was on the verge of breaking down. I rushed out of the house to the woods at the back. I vomited some more and then, because it was an unsightly mess, I kicked some mud over it. I picked up pebbles and stones and rocks and flung them mindlessly at the trees until I was exhausted.

I knew that for my father’s sake and for my relationship with him, it was best that I leave his house. Even if I were to be promised that this would not happen again, there was ill feeling and she had evil plans towards me.

I finally extinguished my anger in the woods, returned to my room, sat on the floor and held a pillow against my chest until the pounding in my heart and head eased up. When I could finally think, I took stock of my situation. That witch, I thought, she’ll do anything to get rid of me. Next time I may not discover it until it’s too late. If one thing burned inside of me with any ferocity it was the need and knowledge that, not only would I survive, I would do well. I decided that my future lay in Beirut, not in Tripoli.

I began to seriously reorientate my emotions. I told myself I would not dwell on unpleasantness. I would move on. I had either to deal with an obstacle or find a path around it. My father’s wife was one of those obstacles that couldn’t be dealt with head on.

I rummaged in my pockets and found that I had about five Lebanese lira to my name, the equivalent of two and a half American dollars. I assessed my situation and packed the few possessions I had: some shirts, the made-to-measure suit, with enough cloth in the seams so that it would last for two to three years. How thoughtful my mother had been! What foresight! She’d had these items made because she knew that she was dying and wanted to ensure that I would always be well dressed – a final act of love for me, her beloved son. I wore that jacket for many years and treasured it as if it were a part of her. When I wore it, I felt I still had her embrace around me, keeping me safe.

Along with my precious jacket, and a couple of neckties, I collected some other small items like underwear, socks and toiletries. I made sure that the things I packed were all undeniably mine so that my father’s wife couldn’t accuse me of theft. I collected these items and wrapped them in a small, thin mattress. Being practical, I didn’t rush off without a plan in my head. I thought I would need somewhere to sleep and should at least have a mattress.

Whenever I am faced with a difficult situation, I immediately try to find a solution. I don’t dwell on the difficulty itself. This has been my saviour every time – my ability to be realistic and yet always believe in that ‘light at the end of the tunnel’. Every time I have looked for it in earnest, I have found it. It is true what they say: ‘In your darkest moments the light really does appear.’

I put the rolled-up mattress on my shoulder, slung a small bag with other things and my schoolbooks over my other shoulder, and stepped out of the room. I looked around; there was no one in sight. Even Baria, obeying my last shouted request, had disappeared. I wanted my departure to be quick and quiet. I tiptoed down the stairs, and hurried out onto the pathway from where I practically ran down to the main road below, leaving my father’s house, without a backward glance or a farewell.

***

It took me three hours to walk down to the intercity bus station with my bundle on my back. I kept looking over my shoulder and walking as fast as I could. I was afraid that someone would discover that I had left, and force me to go back. I knew the worst was behind me. Things are looking up, I told myself. You’ve made a decision and you’re going to be fine.

I believed I was on the road to freedom. Every step I put between myself and my father’s wife was a step towards hope. By the time I reached the bus station I was feeling almost upbeat and happy. I had escaped!

I checked the schedule and caught the first bus to Beirut. That cost me one lira, and with a smile on my face I mentally erased what had happened in the past few hours. I looked to the future. It was an open road and I was heading for Beirut and new possibilities.

The green landscape rolled by on one side and the blue sea on the other, but I had no eyes for such sights. All I could focus on was getting back to school and re-joining, no matter what it took. In spite of all the pampering of my childhood, the unrealistic life I’d led until the point when my mother died, I now faced the reality that I was on my own; and I was determined to get an education.

Chapter Two

When I arrived in Beirut, I was tired but excited. I hauled my bundle onto my back and walked for another hour until I reached the school. I was on home territory and the school was a beacon of promise. My school, International College, or ‘IC’ as it is still popularly known, was the best school in Beirut and the Middle East. The students who attended it were from the most reputable families in Lebanon and the Arab world. There were students from neighbouring countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq… from further afield, countries like India and Iran. Even one of the Shah of Iran’s cousins was a student at the time I attended.

I have to continue my education. It is the only thing. These thoughts consumed me. As I made my way to the school, it was this burning desire that drove me on.

When I finally got to the school, I ran through the gates in tremendous joy. I had arrived safely. My future was assured. I was going to make it!

I stopped short. It was so quiet. Where was everyone? Then I realised it was the summer holidays and school was closed. Was I disappointed? Shattered? No, none of this had the power to put me down. I knew that Mr Ed Sullivan, the head of the boarding school campus, had to be around, and I was sure in my heart that he would find a place for me. I knew that if I thought positively, things would work out. Eventually this became my mantra and has carried me through many tough moments in my life.

When I found Mr Sullivan, all the pent-up emotions of the past few weeks bubbled up and I blurted out my story, ending with the plea, ‘…I can’t live with my father because he’s far away in Tripoli, please sir, you have to take me in, you have to find me a place, it is very important for me to continue my education.’ I told him my fears for my sisters, everything, except the attempt on my life. The words flowed out in a rush. I desperately wanted to continue attending IC and I wanted to stay in the boarding school; and that to me was the only possibility. I felt safer away from Tripoli and far away from my father’s wife. I rattled on, breathless with urgency. By the time I finished I was trembling.

Sullivan was a calm and measured man. He sat down and made me sit down. Then, biting on his pipe, he looked directly at me and said, ‘Does your father know you are here?’

‘No! Please, please, I don’t want him to know.’ I pleaded with him, fell on the floor and clung to his legs. ‘Don’t tell him! I cannot go back. Please don’t call him.’

Mr Sullivan calmed me down and reassured me. He then left me alone for a while, and decided to call my father and inform him that I was safe. My father told him that he would come immediately to Beirut to find a solution and take me back to Tripoli.

When I heard the last sentence I began to cry, and revealed to Mr Sullivan what happened to me with my father’s wife and why I had run away. I said to him, ‘Please, sir, do not send me to my death again, let me work as a servant, please do not send me to my death.’

***

My father arrived in Beirut early the next day. He was very moved. His English was weak so I had to translate what he was saying to Mr Sullivan. It was clear that Sullivan had thought about it overnight and had decided that he would not allow me to return to Tripoli.

He said to me in English, ‘Why don’t you tell your father what his wife did?’ I replied, ‘Please do not do that, I do not want to ruin their relationship.’

‘Your son is a good boy,’ he told my father. ‘It is clear that your wife does not want him. I have no objection to him staying with me for a week or two until the school opens its doors and we try to find a place on its campus.’

But my father insisted that this was not logical and that he would leave no room for his wife to bother me or hurt me.

‘I hope to register his sisters at the American School for Girls in Tripoli for them to stay in the boarding school,’ he told Mr Sullivan.

I insisted that I wanted to stay at IC and that Mr Sullivan had offered to support me.

My father reluctantly agreed and offered Sullivan some money to spend on me.

Sullivan said, ‘Give it to Akram.’ And my father gave me 25 lira.

‘OK,’ said Mr Sullivan. ‘You can stay with me until the end of September. But,’ he added, a little mock-seriously, ‘you’ll have to help around the house.’

Overnight, I went from being a spoilt child who had never done housework to someone who was helping to clean and tidy an apartment. We worked together and in no way did he make me feel beholden to him. I was so grateful that I willingly helped him. He had a flat off campus and a one-bedroom suite on campus so he could stay and supervise the boys in the boarding school.

Life throws many strange people one’s way. On the one hand I had people connected to me like my father’s wife who wanted to kill me, a stepfather who had no faith in me and didn’t want to have anything to do with me; on the other, here was a stranger who was ready to open his home, his heart and his generosity to me.

***