Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

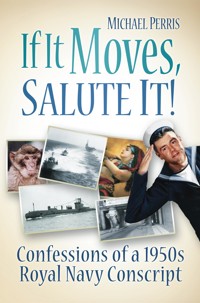

If It Moves, Salute It! relays the uproarious experiences of a young man in the navy during the twilight years of National Service, the late 1950s. A series of encounters help to influence his progress from raw recruit to reluctant adulthood, encompassing his journey through the hazards of training to a submarine depot ship during a visit to Belfast during 'the troubles', a WW2 sub in the Mediterranean, and on a high-profile tour of Scandinavia where he fell in love. The memoir also reveals service life, dress and traditions as they were at the time, many now abandoned or replaced from the modern fighting forces. After clashing with authority on the first day, Mike Perris resolved to keep out of further trouble during the remainder of his call up – a commitment he singularly failed to achieve. After surviving a disastrous security exercise and a simulated atomic bomb attack on a reserve fleet ship, he found that life in the forces was just as eventful off duty as on. This is a lively account of time spent in the navy at the end of Britain's National Service era.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

If It Moves,

SALUTE IT!

If It Moves,

SALUTE IT!

Confessions of a 1950s Royal Navy Conscript

MICHAEL PERRIS

Dedicated to the memory of my wife Anne, who enjoyed a good read.

First published 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Michael Perris, 2011, 2013

The right of Michael Perris to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7509 5358 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Chapter 1

Your Country Needs You

Chapter 2

If It Doesn’t Move – Whitewash It

Chapter 3

Suitable Officer Material

Chapter 4

A Break in Security

Chapter 5

Shore Leave

Chapter 6

A Ship Named Cleo

Chapter 7

Highland Fling

Chapter 8

Escape

Chapter 9

Never Volunteer

Chapter 10

Welcome to Belfast

Chapter 11

Scandinavian Smorgasbord

Chapter 12

Fleet Exercises

Chapter 13

Party Time in Tangier

Chapter 14

Maltese Cross

Chapter 15

Sicilian Drop-out

Chapter 16

Victory in Sight

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to Colin and Marina for reading through the draft, pointing out the mistakes for correction, and making invaluable suggestions for improvement. They were even kind enough to encourage me by saying that they enjoyed it.

INTRODUCTION

‘Pressed into service means pressed out of shape’

(Robert Frost, ‘The Self-Seeker’)

I originally wrote most of this book several years ago. In fact, I realise now that it was probably more years ago than I care to remember. I penned it mainly for my own interest and without any ambition to become a writer.

So why did I decide to have it published now, after all this time? Well, there were several reasons, one of which was the fact that the book is about my time as a national serviceman in the late 1950s, and it is coming up to the fiftieth anniversary of the last national serviceman to leave the forces. And there aren’t likely to be any more – not for a while anyway, though many people have a sort of nostalgia for the old days and would like to see conscription brought back in again for today’s youngsters.

During modern times, there have actually been two separate periods of conscription in the United Kingdom. It was first introduced following the outbreak of the First World War, when the Military Service Act of 1916 decreed that all single men between the ages of eighteen and forty-one were liable for military service – unless they were ministers of a recognised religion or were widowed with dependent children. Before the war was over, the age limit had been raised to fifty-one and married men were no longer exempt. It was not until 1919 that the Act was finally abolished.

And that would have been that if Hitler hadn’t decided that he was going to invade Poland some years later. With war seeming inevitable, a number of precautionary steps were decided upon and Parliament passed the Military Training Act in April 1939. This decreed that all single men aged twenty and twenty-one years of age should undergo a six-month period of basic training which would then be augmented by annual refresher courses. Unfortunately, the outbreak of war put a new complexion on this idea and instead Parliament had to pass the National Service Armed Forces Act, which made all men between the ages of eighteen and forty-one liable for conscription. Single men were to be called up before those that were married. Provision was made for those judged to be employed in essential services to be exempted from duty, as well as conscientious objectors. This led to various inconsistencies, as different interpretations were given to the meaning of ‘essential services’ and to various objections to serving with the military. At one stage, conscripts known as ‘Bevin Boys’ (named after the wartime Labour Minister Ernest Bevin) were even drafted into the coal mining industry. Nevertheless, by the end of 1939 over 1.5 million recruits had been drafted into the forces, over a million of whom had gone into the army. By 1942 call-up had been extended to men aged eighteen to fifty-one and women from twenty to thirty years old. In theory this included pregnant women, but there weren’t any examples in practice.

By the end of 1945, when the war was at long last over, all women were released from duty, together with skilled men who were needed urgently for trades such as building etc. Some form of conscription carried on and it wasn’t until 1949 that the last wartime conscript was finally released back into civilian life. But that was not to be the end of conscription. The National Service Act was inaugurated in 1948 and it required all fit and healthy males from the ages of seventeen to twenty-one to serve in the armed forces for a period of eighteen months. They were then to remain on a list of reserves to be called up in the event of a conflict. By late 1950, largely as a result of the Korean War, the period of training and service had been increased to two years and national servicemen served with distinction in a number of combats around the world, including spells in Cyprus, Kenya, Malaya and the Battle of the Imjin River, as well as in Korea. Officially conscription finally ended in December 1960, but due to deferrals, the crisis at the time of the erection of the Berlin Wall and a general confusion over periods already served, the last conscript left the Army Pay Corps on 13 May 1963. The honour of that place in history went to a Lieutenant Richard Vaughan.

At this time, the view of the regular armed forces about conscription was clear enough, though I don’t suppose it had anything to do with my service. You could almost hear the sigh of relief coming from the direction of Admiralty House when, a short time after I was ‘demobbed’, it was announced that they were going to end all national service. Then, to the Civil Service’s dismay, it was discovered that there were still a number of excused draftees left over that they had overlooked.

Some youngsters’ service had previously been deferred for a year or two because of various health, college, family or job-related problems and so it was not until May 1963 that the last national serviceman quit the services – from the army. The navy had long since stopped taking any more conscripts, citing as a reason that the short period was insufficient for the thorough training of recruits in that branch of the military.

But this book is not just about national service. It’s also about a way of life and a lot of traditions which are fast disappearing from the modern navy. It seemed a pity not to record some of them before they vanish for ever and the many priceless episodes which interspersed a somewhat routine life at sea bear testimony to the fact that it wasn’t all work. I’ve tried to give my story a flavour of what it was like to wear bell-bottoms, go for a ‘run ashore’ and afterwards to try and climb up into a hammock. How it felt to curse your mates when they are the pretend enemy in a war game, and were dropping grenades on to the casing of your submarine to let you know that you’ve been detected and destroyed. It’s then that you realise that next time it could be for real! Throughout, I’ve tried to tell it as it was; warts and all, some may think!

I should confess that I wasn’t personally involved in every escapade described herein. Some of the events were recounted to me by fellow servicemen and so I can’t vouch that it wasn’t coloured a bit in the telling. I have used fictitious names for many of the characters I met and shared time with. It seemed kinder and fairer that way!

Oh, and the final reason for only now bringing out a book written about events that happened fifty years ago, was that the publishers also thought it made a good story. I hope you do too!

The opinions expressed by characters in this book are neither those of the author nor the publisher and are included to illustrate the period described. Occasionally, language used is ‘of its time’ and is not intended to cause offence.

CHAPTER 1

YOUR COUNTRY NEEDS YOU

A plaque on the desk claimed that the man sitting behind it and regarding me rather quizzically was a Chief Petty Officer Davies. I wasn’t sure about the importance of a petty officer in the navy’s hierarchy, let alone a chief, but I guessed that it probably wouldn’t be a good idea to get it wrong. He certainly looked very smart in a double-breasted, dark navy blue suit, with gold-coloured buttons and complementary gold lapel badges. His white-topped, peaked cap, complete with more gold badges, had been placed on the desk in front of him. I thought: ‘I could look good in a uniform like that.’

I hesitated for a moment, not knowing quite how much respect to show.

‘Can I help you sir?’ he enquired, saving me the trouble. I probably didn’t realise it at the time, but it was going to be quite a while before anyone called me ‘sir’ again.

I showed him the official-looking letter of introduction that I had received.

‘I suppose you want the army or the air force,’ he said, rather caustically I thought. But he seemed to perk up a bit when I told him that I had thought more in terms of the navy.

It didn’t seem a good idea to tell him I believed the navy might be the least worst choice of the three. I had sat through all those heroic navy films with John Mills and Richard Attenborough, and although it looked as though it might not be all that safe at sea, it was probably better than either of the alternatives. Anyway, I’d heard you got cheap cigarettes in the navy!

‘I’ve been thinking about joining the navy for some time,’ I said eventually, trying to look a bit like John Mills. I even half-believed it myself. I had heard somewhere that it was the most difficult of the services to get into, so logically it should be the best choice. At least I would probably be some way away from home. Not that I was particularly desperate to get away, but I rather liked the idea of free travel.

‘Isn’t it called the senior service?’ I asked hastily – and probably a bit inanely. At the time it was all I could think of to say. I had been looking at the recruitment slogans on the way in – and illogically remembered the brand of cigarettes with the same name.

‘Have any of your relatives served in the navy?’ he asked. He didn’t sound very concerned either way.

‘Yes I think so,’ I said, remembering that an uncle of mine had once served in the Royal Navy during the war – or maybe it was the Merchant Navy, I couldn’t be sure. Luckily he didn’t seem greatly interested anyway.

‘You’ll have to have a medical,’ he said doubtfully. ‘We’ve got a doctor here at the moment, so if you go and wait in reception we’ll do it now.’

I joined three or four others who were sitting on chairs in a row near the door. From here they were called one at a time into a side room, but it was nearly an hour later before my name was called and the receptionist said I should go in and see the doctor.

I stripped to the waist as directed and presented my body for inspection. The short, elderly doctor regarded it quizzically through thick, rimless glasses and then, not content with merely looking, he proceeded to first prod it and then press the end of a stethoscope against various parts of my front and back. After some more thumping with his fingertips on the back of a hand placed at various strategic parts of my body, he pronounced himself satisfied and we moved on to the next stage.

As instructed, I sat down on a chair opposite him and alternately crossed one leg over the other while he tapped on the knee with a rubber hammer and watched to see what reaction it provoked. I gathered from his expression that everything so far was in good working order. Then I stood up again as directed and dropped my trousers and underpants to the floor. It was then that I began to get concerned. The doctor held my privates in one hand and told me to turn my head alternatively to each side and cough. At the time I assumed that this was all part of a vital medical test, but later I wasn’t so sure. It even crossed my mind that perhaps he just liked doing it. I hastily pulled my trousers back up and hoped he’d washed his hands!

‘How do I stand, Doc?’ I asked, trying to sound unconcerned.

With pursed lips, he seemed lost in thought. ‘That’s just what has been puzzling me too,’ he finally remarked. As he burst out laughing, I realised it was his little medical joke.

Before I could think of a suitable reply he led me next door to a dimly lit room where he announced that he was going to check my hearing. I stood in one corner while he first whispered something in the opposite corner and then asked if I had heard what he had said. I told him that it had sounded to me as if he was reciting the days of the week, which appeared to be the right answer. He declared that I had passed the hearing test.

There didn’t seem much else of me to check, except of course my eyes, and eventually they got round to those as well. First of all I had a test for colour-blindness. At the time, the significance of whether I could distinguish between red and green escaped me, but months later I was to find out. In any case I satisfied them on that point and moved on to the eye chart. By now, I was beginning to enjoy myself and had hardly got past reading off the first two or three rows of letters before I was declared fit in all departments. I wasn’t sure whether to be glad or sorry, but as it turned out it didn’t seem to matter either way, and a month later I got a letter telling me to report for duty to HMS Raleigh. As an afterthought the note suggested I should bring along my own toothbrush and shaving gear…

I was nineteen years old and had just failed the first year’s exams at college. At that age you rarely know for certain what you want to do in life. You’re too old and grown up for being a ‘teen’, but somehow you’re not yet ready to conform to being an adult. So until I had made up my mind, I had decided to take a job driving a delivery van for an electrical wholesalers in Brighton.

One winter’s evening, probably driving too fast along dark Sussex lanes in the rain, I had gone around a corner and suddenly came across a cow standing in the middle of the road. It must have strayed out of its field, or something, but it was an even bet as to which of us was the more confused. I swerved to try and avoid the obstacle and at that moment the cow decided to panic – closely followed by me. As it tried to get past there was a crash against the side of the van and, with me still hanging on to the steering wheel for dear life, we all ended up on the grass verge.

Apart from the cow’s dignity and my pride, nothing else appeared to have been hurt. The only damage was to the side of the van. So, after a few moments I drove on and hoped it wouldn’t come to anything. The cow meanwhile had given me a disdainful look and ambled off into the night. To make things worse, I didn’t get much sympathy when I turned up at work the next day either. They even suggested that I should get some glasses.

A week later I got a message to go to the manager’s office.

‘It’s your lucky day,’ said Mr Daniels as I entered. ‘This time…’ he added, slowly and rather ominously, I thought. ‘The insurance will pay for the damage, and the company has decided not to take it any further.’

It had been a couple of weeks ago now and there was still a bit of a dent in the side of the van. As the evening papers had put it succinctly, ‘the vehicle had come into contact with a farm animal’.

Inwardly I breathed a sigh of relief. Happily for me, it looked as if the company couldn’t believe that a cow had caused the damage, but failing any other cause they had decided to give me the benefit of the doubt. Things seemed to be looking up, after all.

I found that my optimism was short-lived. The very next day I got a letter in the post saying that as I was over the age of eighteen and as I was no longer in full-time education, I might be liable for national service instead. I had been half-expecting this to happen, but it was still a bit of a shock when the official letter actually landed on the doormat. I was instructed to go along in a week’s time for an interview at the nearest employment office. If necessary they would probably arrange to give me a medical check-up as well. Presumably to see if I was fit enough to die for my country, I thought; but at least they were very polite about it.

I had the distinct feeling that I’d only just got over one problem and blow me if I hadn’t landed in the thick of it again! It looked as if I was to be a victim of ‘Murphy’s second law’ which, if I remember correctly, states that for every cloud with a silver lining there’s often another one waiting around the corner when you’ve gone out without a raincoat.

Over the next few days I had to endure the mock salutes and military jokes of my fellow workers. So it was with some trepidation that I got a day off work and caught the bus to the local labour and employment office, which apparently doubled up as a forces recruitment centre. Here my fate was to be decided and by the time I had caught the bus back home again, the die had been cast. It seemed that I would be spending the next two years in the navy. I just hoped that it wouldn’t be anything like the film Two Years Before the Mast.

CHAPTER 2

IFIT DOESN’T MOVE – WHITEWASHIT

According to the address and instructions that I had received in the post, HMS Raleigh was located somewhere near Plymouth on the Devon coast. And so, following a fairly long and tedious journey by train and ferry, I eventually stepped down from the local bus and out into pouring rain at the gates of what I now discovered was a naval camp and not a ship at all. Apart from a lack of barbed wire, it reminded me of the PoW camps that were shown in the popular war films of the time.

Lines of dark wooden huts disappeared into the misty distance. On the right-hand side, just inside the wooden entrance gates, stood a larger hut which I later learned was the guard house. Next to it there appeared to be a reception and an administration block where I reported. Then, after completing and signing various forms (which appeared to make the Admiralty responsible for any disasters that might befall me while in their care), I was directed towards yet more huts known as the New Entry Block. This, it transpired, was to be my home for the next six months while I completed initial training. By the end of that period, I had learnt how to march in a straight line, how to wash my underpants, to interpret orders, fall in line, get up, go to bed, repair my own socks, iron concertina-looking trouser creases, cope with bullies, sleep in a hammock instead of a bed, avoid getting the pox and any number of other things that they said would come in handy in later life.

For the next two years, in fact, they would become an integral part of my life in the forces. Some of the things I spent time practising, seemed at the time to be pretty silly and unnecessary but later, I learnt that they perhaps had more relevance than I had realised. Throughout the rest of that first day a lot more, rather dejected-looking initiates like me, arrived spasmodically at the camp. Some came late, some got lost on the way, and two didn’t turn up at all!

As more new recruits arrived we tentatively started to chat and get to know each other. It soon became clear that we were a pretty motley crowd, certainly not suited to any sort of disciplined combat. There was Tim Reynolds, who had been to a minor public school somewhere, hated it and wanted instead to be a farmer. The last thing he wanted was to waste his time doing national service. Then there was Phil Roberts the Teddy boy, with long sideburns, Brylcreemed and combed-back hair, strangulated clothes and ‘winklepicker’ shoes. He didn’t mind being there – for a time anyway, while they stopped looking for him! He stole anything that belonged to authority, but wouldn’t think of stealing from his ‘mates’. There were apprentices, milkmen and assistant lorry drivers. There were a couple of young unemployed mine workers and a trainee bank clerk. In fact anyone who couldn’t skive out of doing his time in the forces or managed to fail the medical examination for one reason or another. There were even a few youngsters who were looking forward to it! By the end of the evening, we had all shared each other’s problems, said goodbye to civvy street and most had resigned themselves to what we all agreed would be two wasted years.

Next morning, once we’d breakfasted and collected our clothing issue, we changed and assembled on the parade ground. We had gathered that we were there to learn all about marching and drill. Sheepishly we gathered in front of a chief petty officer and formed ourselves into three shambling, more-or-less straight lines. Meanwhile, the chief just stood there silently, his hands behind his back, and his head thrust forward in a slightly menacing attitude. The neck beneath his well pulled-down cap was sweating and swathed in a dirty bandage.

At last he came to life, gave a sort of twisted grin and bellowed out: ‘My name’s Burt. Some people call me Burt the bastard. Soon you’ll be finding out why.’

He gave us another lengthy examination, slowly walking up and down along the irregular lines of new recruits.

‘Gawd,’ he exclaimed loudly at last. ‘I’ve seen better formations in the Come Dancing programme on telly. You look like an advert for birth control.’

He scowled at Shepherd. ‘Unless you are about to change sex,’ he called out, ‘clasp your hands behind your back when you stand at ease, not in front of you. Only Wrens stand like that, and they have a very good reason.’ I discovered that Wrens were members of the Women’s Royal Navy and during the course of the next couple of years I not only had to learn new words, but a whole new language.

CPO Burt paused for a moment while he gathered his thoughts. Then, after giving us the benefit of another scowl, he began what I soon realised was his standard welcome to all new recruits.

‘Now, let me make this clear,’ he shouted, ‘I’m going to make your lives bloody miserable. If you’ve any ideas about enjoying yourselves on the parade ground – forget them. You’re here to work and I’ll see that you do. You’ve got two weeks to learn what the regulars learn in five, but you’re going to do it better than them. You’re going to do it until you get it right, see. I haven’t had a failure yet and I promise you I’ll not get one this time either.’

It was the longest speech I was to hear him make during the next two weeks – without a stream of abuse and swearing, that is!

‘You play ball with me and I’ll play ball with you,’ I heard ‘Taffy’ Edwards whisper behind me. A little too loudly, as it turned out. I grinned; and that was to be my first mistake.

The chief marched straight up to me and, with his now-reddening face only inches from mine, bellowed out, ‘So you think it’s funny do you?’

‘No Chief,’ I managed to answer, reasoning that it wasn’t a good idea to have a clash with authority on your first day.

‘Well,’ he shouted, ‘see if you find running round the parade ground twice, funny instead. AT THE DOUBLE!’ he bellowed. There seemed no alternative but to obey his orders. I started off at a jog around the vast tarmac square.

By the time I was about halfway around I began to realise that I had learned two important lessons – lessons which would largely influence my next couple of years. First of all, I began to realise that the career servicemen, who were in charge, didn’t have much time for us ‘temporaries’. During our training, we were mostly under the watchful eyes of either petty officers or chief petty officers, who weren’t really commissioned officers in the traditional sense. Perhaps as a result, they mostly considered us a bit of a distraction from normal service life and a waste of their time and efforts. From their point of view, we wouldn’t be there long enough to be of any real use!

The next thing I become conscious of was that if I tried to play the fool with the POs and CPOs in charge, I was going to have a miserable time for the next two years. There and then I resolved to keep my head down and bend with the wind of authority instead of railing against it. As I often heard said later, ‘You can’t beat the system’.

I completed my two laps of the parade ground and rejoined the others without another word.

At the time of my original arrival at the camp and during my initial appraisal, I had happened to mention that I’d studied a bit of engineering. At that point they decided that I should join the mechanical engineering branch, known to everyone else in the navy as ‘stokers’ – though there wasn’t much to stoke these days. I’d actually said that I had done a bit of electrical engineering, but they presumably had enough people already in the electrical branch. Or perhaps it was just the navy’s sense of humour.

Throughout the next few weeks I kept my head down and managed to keep out of any further trouble. There were weeks of intensive activity, with a series of tuition and lectures in naval practice both in the classroom and outside. I became recruit number P/K955741 and I collected the rest of my kit. I was taught to keep my bed and locker tidy, my boots polished and my uniform ironed. I did my ‘square-bashing’, darned my socks with the ‘housewife’ kit of needle and thread with which I had been issued and learned to talk in the vernacular. I discovered that ordinary sailors were in fact ‘matelots’ and that petty officers were POs. On the other hand, they could be ‘chiefs’ if they were chief petty officers and even ‘pussers’ if they were in charge of provisions or stores.

In naval parlance, turning to the left was in fact ‘going to port’, toilets were ‘heads’, watertight doors in ships were ‘hatches’ and going out into the wide world outside our camp (or ship) was ‘going ashore’. The time of day was divided into a number of periods, marked by the sounding of bells over the loudspeaker or ‘tannoy’ system. The ‘first dogwatch’ at sea was the period between 4 and 6a.m in the morning and the ‘second dogwatch’ between the hours of 6 and 8p.m. Then there were the middle, morning, forenoon and afternoon bells or watches. Even more strangely, dog watches only lasted two hours and were split into a series of differently numbered, half-hourly ‘bells’, whilst other watches lasted up to four hours. Windows were ‘portholes’, whilst the lowest form of an officer was a ‘Tiffy’ or Artificer. The officer in charge of a ship was referred to as ‘Jimmy’, or the skipper, but rather confusingly, he didn’t necessarily have the rank of a captain at all.

Early on, I was shown how to use a pay-book to measure the width of the concertina-type creases in my bell-bottom trousers – although by the late 1970s they had been replaced by ‘flares’. In preparation for the restricted spaces on board a ship, I learned how to string a hammock. Eventually, we would have to use them instead of beds but luckily it turned out that they were really quite comfortable if they had been prepared properly.

An essential part of my basic training seemed to involve learning to swear regularly, preferably the navy way. Not just ordinary swearing – I knew how to do that before I joined up – but real, imaginative swearing. I discovered some new and interesting names for parts of the male and female anatomy and eventually got the hang of turning every third or fourth word into a profanity. I even managed the knack of inserting a swear word between everyday terms, such as petty friggin’ officer, but failed miserably when it came to inserting swear words in the middle of other words. Two of the less offensive examples I encountered in the first few weeks were the ‘kitsoddingbags’ that we had been issued with and the ‘lieubloodytenant’ who was in charge of our group.

During my early induction as a stoker, I discovered that the cardinal sin as far as my branch of the service was concerned, was to be involved in a ship ‘making smoke’. It was pretty much equivalent to having a car with a smoky exhaust, but in the navy it was considered to be a far worse transgression. It was a sign of inefficient burning of fuel and would make a ship more visible to an enemy. It was explained to us graphically by the chief instructor: ‘You can do what you like in the boiler room except make smoke. You can open the air lock and let all the air rush out ‘til the boiler blows back in yer face. But you mustn’t make smoke. The boiler room can even be six inches deep in fuel oil, and you go an’ drop yer bloody fag in it. But remember, if any smoke comes out of the funnel when you are at sea you’ll be up to your armpits in gold braid before the smoke’s cleared the top of the stack. The only time it’s all right to make smoke, see, ’cos you can’t avoid it, is when you are striking up the boiler. And then you get every bloody colour. I mind the time I was striking up while we was out in Gib’, and the lieutenant comes blazing into the boiler room. It was his first trip, see, and he was as green as they make ‘em. He’d been a bloody bank manager or something in civvy street. I think he’d only been sailing weekends before he joined up. Anyway, “You’re making smoke,” he yells at me. “Black and white smoke,” he says. “You wait here a few minutes,” I says, “and I’ll make you friggin’ yellow smoke as well.” Mind you, I wasn’t bein’ disrespectful, see – I did call ’im Sir.’

As it happened, I didn’t have to worry too much about this particular problem since I hardly ever saw a boiler room throughout my naval career.

Before a week had passed in New Entry Block, we were instructed to load up all our gear into kit bags and, together with another 60lb of bedding, we carried them over to our new home in Valiant Block. An alternative name coined for it by Taffy Edwards was Stalag Luft 2½ and it was right over on the other side of the camp. Like it or not, it was here in Room 23 that I was to spend the rest of my time at HMS Raleigh. I remained there until I had completed the rest of my basic training and ultimately my first real taste of navy life.