9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

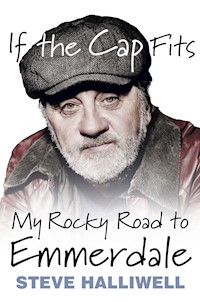

Steve Halliwell is best known as the loveable patriarch Zak Dingle in the hit TV show Emmerdale, a part he has played since 1994 and which has led him to become one of the UK's most recognisable and treasured soap stars. Yet before he found success on the Yorkshire Dales, Halliwell spent many years desperately seeking work, often spending time on the streets in the search of food. This warts-and-all story of Halliwell's rise to fame, where success was only won after great personal struggles, is inspirational to those who wish to establish a life and career for themselves in the face of similar hardships. Going beyond the experiences of one man, If the Cap Fits explores a wider social, cultural and class history that permeated the country in the sixties and seventies, and still lingers today. Above all else, this is an honest tale of rejection and redemption throughout a fascinating and colourful life that will appeal to all who have the ambition to better themselves.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

For Valerie

To the women I have lived with and loved: Jenny, my mother; Susan, my first wife; Valerie, my second wife; Charlotte, my daughter; Lisa, my ex-girlfriend; Valerie – a second time.

Contents

Title Page

Foreword

1 Who Am I?

2 All in a Day’s Work

3 A Different Challenge

4 Sea, Sun and Fun

5 A Different Test

6 A Flight of Fancy

7 On the London Scene?

8 Backward Journey

9 A Soul Mate, Perhaps

10 Reaching the Bottom

11 End in Sight

Postscript

Appendix 1 Quotes from Published Reviews

Appendix 2 All My Joy

Appendix 3 Paintings by Valerie Halliwell

Plate Section

Copyright

Foreword

To all those whom I may have hurt or harmed in my life, I humbly ask for forgiveness. To all those who have hurt or harmed me, I forgive unreservedly. I do not in any way want to glamorise excessive drinking in this book. Where heavy drinking features, it is simply because it is integral to my story, so has to be told if I am to be honest. Heavy drinking has actually caused more harm than good in my life. Part of the sequence of events might be mixed up due to memory failure.

Many thanks to Sandra Kocinski. The sixties black-and-white photographs are by George Broadbent.

Special thanks to Sean Frain, the Bury-born writer, for his help, advice and guidance in producing this book. His works include: The Bury Book of Days, Bury Murders, Cumbrian True Crimes: Murder & Mystery in the Lakes, The Lake District: A Visitor’s Miscellany and many more.

1

Who Am I?

Make it thy business to know thyself, which is the most difficult lesson in the world.

Miguel de Cevantes

I was 18 years old. It was 1964 and I found myself staring hard at my reflection in the Trafalgar Square Wash and Brush-Up, feeling free at last. I had absolutely no idea where I was going, or what I would do with my life, nor had I any idea of how I was going to survive. But this situation felt strangely natural: I was doing the right thing. I certainly felt better about myself than when I was standing at the end of a factory production line, living the life of an automaton.

Often alone, I would walk the streets looking for money or food, but I found London to be fiercely hostile to the penniless. Hours passed as I walked my usually unfruitful walk, but still I held on to the feeling that walking those streets for eight hours was far better than standing at the end of a mind-numbing production line for eight hours. It had almost driven me mad. Perhaps it had driven me completely mad and that is why I found myself alone, hungry and skint – virtually living the life of a tramp.

During the dark nights, I sometimes climbed over the fences of private gardens in exclusive squares surrounded by Georgian houses and I would sleep in the bushes, knowing that I could only be disturbed by someone taking their dog for an early-morning walk, before work. I never was disturbed, despite this being a regular part of my routine. During those walks I would sometimes glance through restaurant windows with hunger knots in my stomach, wondering if I would ever be able to eat in such fine places. It wasn’t out of envy that I would look into those comfortable, affluent scenes, for never would I want to be on the other side peering out at someone like myself, with such a disdainful expression on my face. I was hungry, that’s all. Fish and chips or a cheese sandwich would have served me just as well as fine dining. I wanted to eat, and, more importantly, to know what I was going to do with the rest of my life. I wanted to know what I, Steve Halliwell, would become.

My mother told me that I was conceived at Billy Butlin’s holiday camp at Filey, Yorkshire, but I was born on 19 March 1946 at 40 Lord Street, a red-brick terraced house built for mill workers at Heap Bridge, on the edge of the town of Bury in Lancashire. The village consisted of a few streets and factories, two churches, two public houses (both now closed), a working men’s club, one school, four shops, a stretch of river and a railway line, which were surrounded by fields and hill pastures at the foot of the bleak Pennines.

Some of my earliest memories are of going to the local shop for mother, carrying a ration book, which continued to be issued for several years after the Second World War had ended. I would often deliberately set off in the wrong direction just to hear Mum shouting, ‘Ferguson’s, not Yates’s.’ I didn’t see a great deal of Fred Halliwell, my father, as he spent twelve long hours a day working in a nearby mill – the Transparent Paper Mill – which gave employment to many folk in the area. This man, who sat in the chair reading his newspaper, smoking and mutely demanding silence from my brother and I, was a mysterious figure to me.

My brother, Clive, is two years my senior and we both have many memories of those times, yet when we meet up we hardly ever talk about our childhood. Christmas, bonfire night, whit walks, and the occasional and welcome holiday in a wooden chalet at Gronant in North Wales were undoubtedly the highlights of my childhood, but I suppose the long summer holidays wandering the fields and countryside surrounding our village were the happiest and most memorable times. Looking back on those whit walks I can remember the gathering afterwards at Hamilton’s farm field where we had egg and spoon races, three-legged races and many other peculiarly eccentric games.

We rented our house, which was a small two-up, two-down with no bathroom and an outside toilet, known as a privy. The coal fire was the focal point of our evenings and the family would sit around it, sometimes in silence, sometimes listening to the radio – Al Read, The Billy Cotton Band Show, Archie Andrews and Forces Favourites. TV then was still only a dream. My mind would drift freely during the silent intervals as I conjured up boyhood fantasies from the caves and crevices of red and yellow coals glowing in the hearth, the lights from the flames flickering and dancing across the walls around our tiny living room.

I suppose, materially, ours was an average working-class household common to those times. We had basic food, basic clothing, basic affection, but, for some reason, very little fun together. My mother suffered from polio as a child, which had left her lame in one leg. She was the eldest daughter of Harold Moss, an ex-coal miner who had become very well known in the world of northern brass bands. When still a young man he was known as King of the Trombone and by the time I was born he was a bandmaster for Leyland Motors. Several times he adjudicated at the annual National Brass Band Contest at the Royal Albert Hall. He composed and arranged many pieces and was also a teacher of music.

My mother, Mary Jane, was known to all as Jenny and she often played our piano. Debussy’s wonderful ‘Clair de Lune’ was my favourite, and still, whenever I hear it, I’m taken back in an instant to when I first heard it at my mother’s side. As young boys, my brother and I, alongside the other kids we knocked about with, would spend hours throwing stones into the stinking mounds of chemical foam which meandered along the river. When I was a child I thought all fish came from the sea; I didn’t realise our river should have been full of life. It had died due to all the factory waste that had been tipped in there over the years. Despite all of these things, we kids never questioned the quality of life we had in those days. Children, it seems to me, accept their lot much more easily than do adults. Michael Hopkins was a prime example of this.

He lived across the street with his father and he had difficulty speaking. We sometimes played in his house; games like hide and seek. His father wasn’t too house-proud, however, as the bucket used to save nightly trips to the outside toilet wasn’t emptied on a regular basis. In fact, it was often so full that it was close to overflowing. His father was more in the pub than at home with his son and I felt sorry for the lad.

The Brooks family also lived across the street and amongst them were Billy, Edwin, Lena and Roy. They often had no heating and Lena and Roy, both around the same age as me, would sit around the open gas oven in an attempt to keep warm. I didn’t join in, but some of the other kids laughed at Roy’s birthday party, simply because his mum could only afford to put on chips, with jelly for dessert. ‘Jelly and chips’ was the taunt of several children for days after that party.

We had no bathroom and on hot summer days my mother would drag the old tin bath into our dirt yard at the back of our house, and then plonk me and my brother into its silvery depths. As we grew up, any other baths we had were at the local swimming pool in Bury. People then were not as obsessed with bodily hygiene as they are nowadays. Different friends had different smells – mostly unpleasant ones! Kids with nits; nurses known as ‘Nitty-Nora the Bug Explorer’; bitten fingernails; speech impediments; fathers with missing fingers, or missing arms even, all lost in industrial accidents; stunted women with bow legs due to rickets; fleas in our beds – these are just some of the early memories which have remained with me across the decades.

Sundays at that time were spent going to the early-morning service with Mum, who was very much involved with the local church, as she was quite a religious person. Dad, on the other hand, was an atheist. This situation set up very early confusion in my mind about what to believe and what not to believe. I had quite strong spiritual feelings as a young lad and listened with a lot of interest to the stories which were told in church, but the biblical phrase ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you’ left a vivid impression and remains with me to this day. It is the one and only teaching I find hard to fault, though, of course, it is difficult to live up to. Even though that ideal was always in my mind, I still managed to get involved in quite a number of fights when I was a young lad. I never mentioned such fights at home, however, for fear of Mother’s disapproval. Dad, on the other hand, enjoyed boxing as a spectator.

This confusion regarding religious beliefs wasn’t helped when I noticed the hypocrisy of the church. They would preach that it was proper to give one of your two coats to your brother in need, yet poverty was rife all around and I didn’t see the church giving up much to help the poor. I wondered why our vicar didn’t give up his large four-bedroom house to the Stone family, who had, if my memory serves me correctly, eight children. They somehow had to manage in a two-bedroom house. Surely giving up the large house to that family would have been the Christian thing to do! I believe that leading by example is the best way of teaching. That vicar’s example, it seemed to me, had taught nothing of any positive value.

The Drakes* were a really tough family who lived up our street. There were four brothers among them – Terry, Raymond, Richard and Johnny, who all fought like caged tigers, so they were generally the leaders of the kids in our village. And thus their often dodgy activities became the pursuits of us lesser mortals. Setting fire to meadows and fields was a major summer amusement and my brother, Clive, proved more inventive than the rest of our gang. He devised a way of setting fire to the grass so that we could watch from the safety of the distant railway bridge, which was known as Twenty-three Steps. Clive would light a cigarette pinched from our dad’s packet when he wasn’t looking, lay it in the grass, pile a few matches part-way along and then pile some dry grass on top of that. As the cigarette burned down towards the matches – bingo! – field or meadow was soon ablaze. We called this field-burning activity ‘swealing’ – I recently looked in the dictionary and it turns out that it is a genuine word, which surprised me.

The railway line running through our village was a little branch line which ran into Duxbury’s Paper Mill, in order that trains could bring in pulp and then take out the finished paper. Ernie Hardman was a kid of my age who lived at the other end of our terrace. One day he and I hung onto the buffers of a slowly moving train, laughing hysterically at our own stupidity. We rode the buffers until we could hold on no longer and then dropped onto the railway tracks, watching the little steam engine clang and puff away into the distance. We would then hurry to tell our friends of our latest achievement. Walking across a pipe which crossed the river was another dare that all the boys in our village had to do – if they wanted to fit in, that is. If not, they would then forever be branded a ‘soft-arse’.

One way or another I always seemed to find myself in trouble and, as a result, I was given the cane at school almost as many times as a mate of mine named Barry Nicholson, who also had a reputation as a troublesome lad. When I had almost attained the kudos of being the most caned boy in school, ‘Baz’ would always go and beat me to it. There was an old piano in his home too and he could play it by ear, as he was a naturally talented musician. He enjoyed singing and would do so very loudly as he walked to and from the local shop. In later years he became a club singer whose stage name is Barry Gee.

Another early showbiz influence was Keith Smith. He would perform wherever and whenever he got the chance. He would sing a song, play the mouth organ and one of his finest party pieces was doing Hilda Baker impressions. He was only about 10 years of age at the time, but he already had business cards printed which announced: Keith Smith – the Wonderboy of Heywood. Every Saturday morning I would get my spending money and walk from Heap Bridge to Bury town centre in order to watch the morning Odeon screening, which was known as the kids club. One Saturday Keith and I were in the cinema and, because he didn’t want to miss any of the film by having to go off to the toilet, he urinated under the seats instead, which I found hysterical at the time. No wonder those old cinemas stank so awful.

One Saturday a pea-souper smog, a mixture of low cloud and smoke from the hundreds of mills and factories in the area, descended on our village. These terrible smogs were very bad for the health and caused severe breathing problems in some cases; later legislation was passed which enforced smokeless zones. I was 10 years old at the time of the pea-souper and I had never witnessed anything like it before. I could hardly see more than a few inches in front of me. I decided I would go outside and ‘disappear’ into the gloom, becoming the ‘invisible man’ or, I should say, ‘invisible boy’. I walked very slowly and carefully to the churchyard, which was near our house, and I noticed what looked like bits of soot mixed in with the fog. It was incredibly dense and the eerie silence was just a bit scary.

I then decided I would shout out anything that came into my head. I bellowed from the thick gloom as there was no fear of being identified. I shouted whatever I wanted, including ‘FOGBALLS!’ after I had wondered if the fog could be made into balls, as one could do with snow. Of course, I knew this wasn’t possible, but my imagination ran away with me in that surreal setting. I also shouted, ‘I’M NOT ’ERE!’, though I don’t know why.

After this bout of acting the goat, as Mum would call it, I began to wonder if any of my family were lost in this smog, so I set off for home, but had to tread very carefully in order to avoid bumping into the trees. I thought I would enjoy just one last shout as I neared the house, so ‘TIT!!’ echoed around the village before silence prevailed once more. When I went inside, my brother was home, but he never mentioned hearing a lunatic shouting in the smog. Mum returned from the nearby shop; then Dad got home from work and Sandy, our cat, suddenly appeared at the door, so everyone was safe.

I also have a vivid memory of jumping out of bed late one night and going over to the window in order to see the red glow of a steam train chuffing along the distant tracks as it blew its whistle. I must have been only about 4 or 5 years of age at the time, yet I imagined those distant trains were heading off to far-flung places such as America, France, Australia and other exciting foreign lands. I can remember thinking, One day, when I am older, I will get on one of those trains and set off on an adventure. These memories still evoke that far-off childhood dream – of things yet to be discovered, of a future yet to be lived. Alas, it wasn’t long before I found out those trains were just going up the line to Rochdale, about 6 miles from our home.

Both my grandfathers had been coal miners and I can think of no better way of describing their work than as slavery. I visited the mining museum at Wakefield years later, in 2012, and was utterly disbelieving of what my grandfathers were expected to do each working day. For most miners there was no other way of keeping a roof over their heads and food in their bellies. My father and uncle hadn’t gone down the mines, but they still had to graft long hours in order to make a living. This incredibly hard way of life left a lasting impression on me and I felt I had to find another way of living. I was determined that I was not going to be yet another ‘slave’. But how could I free myself? It seemed an overwhelming task.

Glynn Harman was another childhood hero of mine. He was about a year older than me and proved to be a good footballer and a good fighter. He also had a knack of finding bird nests, as he was good at climbing trees, as well as digging out underground dens and making bows and arrows. He had three older brothers who had taught him all these tricks. Some of my earliest memories are of him taking me to farms where we would steal apples and turnips. Glynn later became a professional footballer.

That small settlement known as Heap Bridge produced some real characters, none of whom could be described as boring. Glynn was small, strong and wiry. He usually spoke fluently, but occasionally stammered in his speech. One day we were walking through some fields far from home when he suddenly stopped and said, ‘Sssssnipes nest in fields like this.’ He was right too, as one flapped away rapidly after we disturbed it. Glynn found its nest and we arrived home later with an egg each. We blew them in his backyard after putting a pin-hole through both ends. Robbing nests was common among young lads in those days, but is now thankfully rare (as well as highly illegal, not to mention cruel). Glynn also made spears, catapults and pea guns, which were useful for firing at the backs of heads!

Another clear memory I have is of walking in the fields one hot summer’s day with Glynn, my brother, Clive, and a few other lads, when we were joined by a stray dog we named Dirt Boy. He remained with us all that hot, shimmering day with the sun beating down on a countryside in full summer glory. But as we arrived back at the village, the dog, for some unknown reason, ran straight under a passing truck and was killed instantly. All of us tried to be macho by holding back the tears, as being tough and seemingly unemotional was the norm in those days, just after the Second World War. This is possibly why Mum teaching me to be quiet and Christian in nature was always at odds with the peer pressure of what was expected of me as a working-class lad in a working-class village.

One Christmas my brother and I were given boxing gloves and we would box each other in the house or in the backyard. Other lads would come round and we would have mini-tournaments. Clive and I were in the house having a few rounds one day when his sock started to hang loose and I must have stood on it at the same time as I threw a cracking straight left – Clive was literally knocked out of his sock. Dad, who was watching from round his newspaper, let out a rare laugh. I felt sorry for my brother as he was clearly angry, him being two years older than me. However, he later made me pay for that punch, during a backyard three-rounder, which was the beginning of my long drawn-out nose-flattening process.

It wasn’t until years later, in fact, that I found out that the district of Heap Bridge was considered a no-go area by young lads from other parts of Bury. We had a reputation of being ‘hard-nuts’, but this particular ‘hard-nut’ child spent some lonely nights silently crying, so as not to disturb his brother, who was sleeping in the next bed. I was sad, confused and frustrated by my seemingly loveless father, my religious mother and my introvert brother. I didn’t know how on earth I could help them to be happy, or myself for that matter. It never dawned on me then that almost everyone is unhappy a lot of the time.

There were always some things to look forward to though, such as the whit walks, which helped take our minds off the harder side of life. St George’s Church always employed a Scottish Pipe Band at such times and one of the highlights was seeing the bonny girls in their kilts, velvet jackets and plaid socks. They seemed such exotic creatures and I always imagined they had come all the way down from Scotland just to be with us. So I was a bit disappointed to find out that they came from Oldham, just a few miles up the road. I went to Heap Bridge Primary School and behind it were some old air raid shelters, underground concrete bunkers that had been built during the Second World War. They were very damp, smelly and cold. I don’t know who first came up with the idea, but we took to piling dry grass in the shelters and setting it alight. The object of this game was to see who could stay in the shelter the longest, despite suffering from the effects of smoke inhalation. Most would come running out with deep barking coughs and streaming eyes, only to be jeered at for giving in too easily. I am certain that was a contest I never won.

Clive and I did, however, win quite a number of bogey races, racing in a very fast cart built by our dad, using wheels from our old pram. I would push while Clive steered and these races usually took place on the Oller, which may have been the Lancashire rendering of ‘hollow’. It was just a bit of spare land. Bonfires were lit on the Oller in November, as well as at Waterfold Lane and on Lord Street, where I lived. These had to be carefully guarded, as lads from other areas, or even our own, would attempt to raid and steal the wood.

A huge fight kicked off one Saturday afternoon when a gang of lads from Prettywood, a district less than a quarter of a mile from Heap Bridge, raided our Lord Street bonfire. My brother received a cut under his eye during a stick fight and this raised conflicting emotions in me. Should I turn the other cheek, as I had been recently taught in church, or should I get stuck in? The matter was quickly settled for me by a blinding migraine attack as the Prettywood gang got away with quite a lot of our wood. One year the Lord Street and Oller gangs pooled their resources in the hope of enjoying one enormous bonfire. We were all sat around a little camp fire one evening as we guarded the precious wood. Richard Drake arrived and suggested we all had a walk over to Seven Arches. We didn’t usually disagree with the Drakes, so we set off down Waterfold Lane. Someone then shouted, ‘It’s a race,’ so off we sprinted like whippets, but by the time we reached the first of the seven arches, we realised Richard had disappeared. Fearing the worst, we ran back towards the village and ahead we could see billowing smoke and the glow of fierce flames lighting up the night sky. Richard had hidden paraffin and had then sneaked back and lit up the Oller. Despite a fire engine being called to the scene, we lost all of the wood we had been collecting for several weeks – and this with only two days to go till 5 November. This wasn’t the first or last time someone would set light to our bonfire before the official date had arrived.

Another game we played around this time was very dangerous, to say the least. This was dropping bangers down cellar grids and the biggest dare was to drop one down into Walsh’s cellar, the local greengrocers, as Jim Walsh would definitely chase us. If he caught any of us we would receive a good hiding for our troubles. One night I plucked up some courage after much goading and dropped a banger down that cellar – the loud echoing blast set us off running. The sense of fear was overwhelming. ‘Come ’ere you buggers.’ Big Jim, as he was known, was out, running like a madman and gaining on us. I sprinted into the church grounds to try to make my getaway through the trees. However, my heart was pounding like a steam-hammer. I thought I was going to have a heart attack, so I dropped into the long grass and rolled down the hill, hoping that he couldn’t see me in the dark. It was then that I heard it: a blood-curdling scream, which meant that one of the lads had been caught and was receiving a good thrashing from Mr Walsh.

Sometimes, on a Saturday afternoon, a gang of us lads would walk to Ashworth Valley, where we enjoyed steep woodland walks. At times we would start out at Heywood and walk back up the banks of the River Roch to Bury, all the while playing cowboys and Indians, or Robin Hood, or whatever we had seen that morning at the Odeon cinema. Sometimes just my brother and I would go and we got to know every inch of Ashworth Valley, including all the different ways of crossing the river, which in places was very shallow. We had an old tent and occasionally my brother and I would camp overnight. Clive had an air rifle and I had an air pistol, so we would set up camp, light the fire and then play cowboys and Indians.

We would also place tin mugs and plates around the fire and Clive would shoot at these from nearby trees while I took cover behind some rocks. I would fire through the trees, pretending to shoot at Clive, and could hear the pellets rattling through the leaves. All of these shoot-outs were in imitation of the cowboy films we had seen at the cinema. I suppose it was quite dangerous, but we never thought about such things at the time. Clive was a very good shot and on one occasion he aimed at and hit an empty pop bottle that was very close to my head. Some of the shattered glass actually hit me in the face, but thankfully I sustained no serious wounds.

When we finally settled down and went to sleep we would take the hot stones from around the camp fire and put our feet on them for warmth. I would drift off, dreaming that I was tired from the day’s cattle drive across the prairie. In the morning we would open a tin of beans and place the tin directly on the fire, which would warm them up very nicely. We would sometimes end our walk through the valley at a district known as Fairfield, or sometimes we would walk on to another district, Walmersley, from where we would then walk home to Heap Bridge. When I first went on this walk there was a small café in the woods known as Nab’s Wife (a corruption of the area originally known as Nab’s Wharfe), where you could get a refreshing cup of tea and a Mars bar. You could also get a bacon butty, but we never had enough money for such ‘luxuries’. On one occasion I persuaded Mum to give Clive and me enough money for a bacon butty each, but when we got to the café it was all boarded up and, sadly, never reopened.

I really enjoyed watching cowboy films on these Saturday visits to the cinema, but there were so many random deaths in these films that I spent some of my time worrying about the families of those guys who were always getting shot in saloons or livery stables, even though these characters were baddies, often described as ‘dry-gulching sidewinders’ or ‘bushwacking coyotes’. I also worried about the Indian braves who were usually just left lying around for the vultures. Such little respect for human life really confused me – and it still does today. Those were only movies, but there seems to be just as little respect in real life.

Being a lad from a small village, I believe I had quite a narrow view of life, but things were about to change. I had failed my Eleven Plus exam, which ruled out grammar school, though my brother had managed to get into Rochdale Technical School. My uncle Albert, brother to my dad, also worked at Transparent Paper Mill, but he had progressed to Personnel Manager, so he had been able to send my cousin Keith to a small fee-paying school in Prestwich, south of Bury and not far from Manchester. So Mum, not wanting to be outdone by Uncle Albert, sent me for an entrance exam. I tried desperately to fail it, as I wanted to go to Regent Street School in Heywood, where all of the other lads from the village were going. However, to my horror, they said I had just managed to scrape through. Scrape through? I’d hardly answered any questions and those I did I deliberately answered wrongly. They had obviously passed me simply to get the school fees. This signalled the death-knell of my bond with the other lads. In no time at all ‘Snob’, ‘College Boy’ and ‘Soft Arse’ had all been chalked on our end terrace wall. It was bad enough my brother going to Rochdale Technical School, but me setting off every day in a maroon blazer was, to them at least, unforgiveable.

My first day at the school, Cliff Grange, was also my first time in long trousers. I am sure they were made of horse hair, or some similar material, as they rubbed my legs raw. My new shoes were made of plastic. Mum thought they looked very smart. The school building was an enormous detached house that had been converted into several classrooms and the founder and head teacher lived upstairs in a flat.

As I walked through the door on that first morning I noticed a lot of special needs children queuing up. This made me begin wondering if I had been tricked into going to this school, perhaps because Mum and Dad thought I was deranged. Perhaps they had always known that it was me shouting ‘tit’ in the fog and they had decided I wasn’t a ‘full shilling’. I certainly felt that I didn’t belong. The school seemed very Dickensian and gloomy, especially during times when we lined up in the cellar, or ate our meals down there. During school dinners I was advised to get my ‘dinner pocket’ ready, which meant having a plastic bag in my blazer pocket ready to put food in. This baffled me to begin with, but I soon realised why this was common practice. We were all expected to clear our plates and the food, unfortunately, was disgusting. One meal served to us was nicknamed ‘barley and bizz’. I don’t know exactly what it was, but I would in no way be surprised to hear that it was rat and barley. This disgusting concoction was usually served alongside cold boiled potatoes and was enough to put you off food for life. Another ‘horror’ dish was ‘the rissole’, which was about as appetising as a dog turd. Rissoles usually ended up in the dinner pocket bag and were later thrown over the fence into the grounds of the neighbouring residence. This gave rise to the legend of the ‘rissole tree’, as dozens of rissoles in bags hung from its many branches.

During one lesson we were asked to write descriptions of our homes and one kid told me that he couldn’t remember the colour of his bathroom suite. I could not join him in such trivialities, however, as we didn’t have a bathroom of any colour. So I lied and said ours was green and red.

I felt a little less out of place a year or so later, when Barry and Peter Tracey began attending the school. They were the sons of John Tracey, who was the landlord of the Boar’s Head public house in Heap Bridge. He was also a tinker who owned a fleet of rag and bone carts pulled by ponies, which also belonged to him. He earned a decent living combining these two completely different businesses. Barry was about the same age as me and Peter was a couple of years younger. Barry was a strange mixture: handy with his fists, yet at the same time a rather sensitive soul. He later became a scenic artist for Yorkshire Television.

The head teacher was a local Conservative councillor and part of our ‘curriculum’ was to deliver political leaflets to houses and shops in the area. I wondered how my dad would have felt, had he known he had been working long hours in a mill in order to pay for me to help campaign for the Tories? I was only a young lad of 12, but already I could clearly see that this school thrived on gullible people like Mum and Dad, people who cared about their children’s education, despite their offspring being far from the brightest marbles in the bag. The school also got us kids to write ready-prepared letters to various companies, begging for free produce, which was to be sold at our local charity event in the school. What that charity was I have no idea, though rumours abounded that it was probably the head of the establishment’s political campaign. I couldn’t bring myself to tell Mum and Dad about the realities of this place as I was certain Dad would have replied, ‘What do you know, you’re only a kid.’