Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

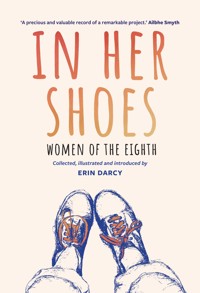

In early 2018, Erin Darcy created an online art project, In Her Shoes – Women of the Eighth, to safely and anonymously share private stories of the real and devastating impact of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution of Ireland. In the five months leading up to the referendum on abortion, the project asked a simple question of undecided voters: put yourself in her shoes. Within weeks, Erin was receiving hundreds of stories from a broad spectrum of experiences of planned and unplanned terminations. By the time Ireland historically voted Yes to Repeal the Eighth on 25 May 2018, the page had gathered over 100,000 followers, was reaching over four million readers each week and had been featured by international news outlets. What began as a solo act of grassroots activism by a mother and an artist had unleashed a national conversation on human rights that would change Ireland forever. Where once there had been silence and shame, now there was honesty and empathy. For 43 per cent of voters, it was 'stories in the media' that influenced their decision to vote Yes. But for Erin Darcy, In Her Shoes was also a distraction from her own heartbreaking loss, loneliness and depression as she grieved her mother's death and sought a community of her own. In time, it became an act of healing, as she connected with other women, mothers and campaigners who felt the same overwhelming need to do something. Here, In Her Shoes: Women of the Eighth reproduces thirty-two of those anonymous stories, representing the entire island of Ireland. Published with their authors' consent and illustrated by Erin, they are powerful testimonies to storytelling as salvation from heartache, stigma and threat. Together, they record lived truths previously omitted from history and signal a monumental change in the social landscape of our country.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WOMEN OF THE EIGHTH

During what was often a fraught and bitter campaign, some forgot the very real people behind the need for reproductive healthcare in Ireland. In Her Shoes helped put those people – and their vastly different backgrounds and stories – front and centre again. We will never know how many untold stories the Eighth Amendment left behind. In telling some of them, this book honours them all.

Tara Flynn, actress, writer and comedian

By changing the conversation, In Her Shoes helped the Repeal movement change Ireland, giving voice to experiences that had been silenced for far too long. This book is testimony to the power of those stories and a moving reflection on a history we should never forget.

Dr Mary McGill, researcher and journalist

It would be hard to overestimate the contribution of In Her Shoes to repealing the Eighth Amendment. I salute the honesty and bravery of the women who told their stories and Erin’s strength and determination in bringing them into the open. This is a precious and valuable record of a remarkable project.

Ailbhe Smyth, Co-Director of Together For Yes and Convenor of the Coalition to Repeal the Eighth Amendment

WOMEN OF THE EIGHTH

Collected, illustrated & introduced by

ERIN DARCY

IN HER SHOES

First published in 2020 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin 14, D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright, Erin’s Story, illustrations and front and endmatter © Erin Darcy, 2020

Copyright, Thirty-Two Stories of Ireland © Individual Anonymous Contributors, 2020

Copyright, The Keepers’ Stories © Individual Contributors, 2020

The right of Erin Darcy and the individual contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84840-784-8

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84840-762-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-785-5

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

The Thirty-Two Stories of Ireland are published in this book with the consent of their anonymous authors.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed by Catherine Gaffney, caegaffney.com

Edited by Djinn von Noorden

Printed by L&C Printing Group, Poland

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland

For my mother, Martha Jane, and the daughters of Ireland.

Born in the United States, Erin Darcy is a mother and a self-taught artist living in Galway, Ireland, since 2006. She has been a contributor toThe Rainbow Way: Cultivating Creativity in the Midst of Mothering and Creatrix: She Who Makes by Lucy H. Pearce and Rise Up & Repeal: A Poetic Archive of the 8th Amendment edited by Sarah Brazil and Sarah Bernstein.In Her Shoes: Women of the Eighth is Erin’s first book.

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Prologue

Storytelling as Salvation:

Erin’s Story

Thirty-two Stories of Ireland

The Keepers’ Stories

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Additional Resources

Notes

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The Facebook page In Her Shoes – Women of the Eighth originated in early 2018 as an art project with the intention of changing undecided voters’ minds in the upcoming referendum on the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution. The grassroots project posted anonymous stories of the negative impacts of the Eighth Amendment alongside a simple photo of a pair of shoes.

In the five months from its creation to the referendum vote on 25 May 2018, the page grew to a following of over 115,000 with an organic reader reach of over four million per week. As an artist, immigrant and mother of three living in rural Ireland, creating and holding the space for these experiences became my contribution to the movement to repeal the Eighth Amendment, a referendum in which I could not vote.

Of the thousand stories sent to the In Her Shoes page, I selected thirty-two for this book, as a representation of the entire island of Ireland. I wanted to give these lived truths a communal space that could be recognised the world over. The anonymous stories are reproduced here with their authors’ consent and remain in their original words, with only minor edits for accuracy and ease of reading. The stories published on the Facebook page have been deposited by the Irish Qualitative Data Archive in the Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI), accessible to the public and protected for future generations. By preserving these stories within the archives and in this book, we enshrine women’s experiences in history where they are often written out.

In Her Shoes: Women of the Eighth, the book you now hold in your hands, describes a changing social landscape, an uprising within myself and within Ireland.

PROLOGUE

It’s bitterly cold and windy but the sun is shining as I stand on the streets in my small conservative town in rural Catholic Ireland. This town is my home, but not my home place and so my American accent softens to match the gentler way of speaking. I’m asking strangers to support abortion rights in a place where it is illegal. The date is 13 January 2018.

Being a ‘blow-in’ is a privilege in many ways. It’s far easier for me to campaign for choice than it is for the friends who have grown up here. In these small towns, where everyone knows everyone’s business, being openly pro-choice can have both professional and personal implications. Abortion is a word said in a hushed tone, not something for which you broadcast support.

‘Would you like to sign to support women’s rights?’

I look for a way to encourage curiosity, to avoid the recoil the word ‘abortion’ can produce. The man passing by shakes his head automatically and moves on before pausing and doubling back. He’s poised like a gundog.

‘What did you say?’ Furrowed brow, hands shoved deep into the pockets of his tan jacket, jaw clenched.

‘I asked if you’d like to sign our sheet to support women’s rights. We’re looking for signatures of support for repealing the Eighth Amendment.’

‘I have daughters!’ he barks. ‘Did you not hear about the woman who died after the abortion in England?’1

We’ve been told to move people like this on, but my adrenaline pulses, my heart races.

‘Don’t you think she should have been looked after better? Had she been able to get that help here, she wouldn’t have been rushing out of a clinic to get her flight home. She would have been able to recover and take her time, under supervision of her own doctor.’

‘I just don’t think they should be using it as a form of birth control.’

I try not to feel exasperated and promise him that no one uses abortion as birth control. ‘Do you think anyone wants to have an abortion?’ I tell him how even the morning-after pill impacts our cycle and it’s not a pleasant experience.

‘Well there should be a cap – there’s people that have three, four, five abortions. They need to take responsibility for their actions. They made that mess.’

The women standing at the stall with me continue talking to other people passing by. Trying to keep my voice steady, I ask him: ‘Should she have those babies instead? Is that who you want raising a child, someone who doesn’t want to be a mother?’ I share with him that I have three kids. No one seems to expect a mother to advocate for abortion. ‘Being pregnant shouldn’t be a punishment. Children aren’t a punishment. All children should be wanted, not raised by someone who didn’t want to do this.’

I can see that he understands. ‘I do think that women should be able to get an abortion in certain circumstances,’ he concedes.

‘Well, it sounds to me like you’re pro-choice then,’ I add quickly. ‘The only way a person can get the abortion under any of the “certain circumstances” is if we vote to remove the Eighth Amendment. If you just put yourself in her shoes …’

It doesn’t come to me as a revelation. It’s a turn of a phrase: don’t judge someone until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes.

His entire disposition changes. ‘I’m not sure I agree with abortion, but you’ve made me think. I need to read some things first.’

Heart racing, I hand him a few of our brochures before he moves on.

Oh my god, Erin, you’re doing it. You’ve got this.

SELKIES

It was the selkies that brought me here. Selkies, I learned from The Secret of Roan Inish,2 are mysterious mythological creatures, half-seal half-woman, that come to shore and shed their pelts to sunbathe in human skin. If someone takes a pelt home, the woman will stay but forever long for home, for the sea, for belonging. I longed for the sea.

*

When I was seven years old we moved from the Puget Sound of Washington to the purple Rocky Mountains of Colorado. High in the sky, as far from sea level as you can get, I would stand barefoot on boulders, surrounded by pines and aspen trees, making wishes into the wind to go to Ireland, to the ocean with selkies, to the land where my ancestors once lived. I roamed the mountains on horseback. In a small ghost town – population 49 – we lived an honest and simple life. I spent my time digging in the soil for remnants from Gold Rush days. I explored abandoned houses and created stories about pilgrims arriving by boat from far away. The days were endless and vast.

Adolescence smacked me in the face with a move back to my birthplace of Oklahoma. It was nowhere near the ocean and far from the mountains. We settled in a typical American neighbourhood of fenced-in back gardens and a paved road out front. The culture shock of school was immense: groups of jocks and geeks, skaters and preps, goths and band nerds. I craved the naivety and sweet simplicity of vast, wild spaces, although it didn’t take long to find my tribe: the misfits, the shy, the artsy, the awkward, the rebels.

At home we were our own little unit, just the five of us: two older brothers, Cody and Trevor, Mom and Dad. My mother was my best friend. We had little money but lived like royalty. Mom and Dad took us on thrilling road trips: we’d sleep in motel rooms with a picnic spread of crackers and canned meats with cheese in a spray can – the height of luxury, I tell you. Living just above the poverty line in America meant brown paper bags from churches with cans of donated food, and yet we were never without.

I grew up with a passion to follow my dreams, like Mom and Dad. The ocean never stopped pulling me to her and I entertained fantasies of returning to Washington, of living in a houseboat near seals and whales and ocean mist, of becoming a marine biologist – a ‘real job’ with a side hobby of art. I considered the Atlantic and fantasised about Rhode Island School of Design, but art school was an impossible financial ask.

Around that time I began to search for a pen pal in Ireland, with the idea of becoming more familiar with the place and the stories I had grown to love. Dial-up internet churned into life, bringing me to the Irish chat rooms. Here were the poets and musicians, the older women looking for love, the perverts and the craic. Here was my escape from Oklahoma. I found a group of Irish people to chat with – and then I met him: a boy, sixteen and ‘sound’. Here I was, talking to a boy from Ireland.

It wasn’t long until I was in love, rushing home from school to see if Steven was online. Night after night he would stay awake into the early hours of the morning while I skipped homework to scheme out our future together, running up phone bills and a hefty collection of phone cards in the process. I drank in his Galway accent as I sat on the floor in my closet, beaming until my cheeks hurt, making him repeat words over and over again.

For two years we talked every day, sending letters and packages until, in the autumn of 2004, he asked his mom for a Christmas gift of a plane ticket that would bring me to Ireland and to him. I was seventeen. How would I even ask my parents for permission to go to Ireland during Christmas break to meet my internet boyfriend? I prepared the speech in my head. I would sit them down and tell them how important this was to me while guarding my heart for the inevitable no. To my surprise they said yes almost immediately. It was the experience of a lifetime, they conceded.

Mom and Dad’s unwavering trust and faith in me led me to believe I could do anything, that I could be anyone. Yet rumours swirled around in school. I became the focus of our psychology class, the teacher dissecting my long-distance relationship, students joining in with jokes about a fat old sexual predator luring me to my death. I had always wanted to shake things up, so going against the grain of what was expected felt all the more thrilling. I would never be the one to stay in town, go to the local state college, have the two kids and a white picket fence. I wanted more. I wanted to travel to Ireland and meet the boy I was in love with. I counted down the days. I cashed in my fifty-dollar savings and applied for a passport.

The day after Christmas my parents hugged me at the departure gate. I navigated the Chicago layover on my own. On the 4,000-mile plane journey I was too nervous to find the toilets. I wasn’t even sure where they were. I sat for six hours, thumbing through magazines and alarming the Irish man next to me with an account of my endeavour.

We landed in Dublin. My stomach all aflutter, I wheeled my giant bag through the exit doors to be met by a sea of faces looking for loved ones. I scanned the line until I found him: tall, dark hair, bright red cheeks and a giant grin. I was engulfed in his embrace, breathing him in, his shyness, excitement and familiarity. The world blurred around us. We were each other’s first kiss in Dublin airport.

The countryside whirled by in a green fuzz. We held hands in the back seat of his uncle’s car, giggly, delirious and lovesick. We arrived at the house, were welcomed in, and I met the entire family. I settled at the table with a cup of tea and stared at a plate piled high with rashers and sausages, eggs and beans, toast and black and white pudding. Aunts and uncles asked all of the questions. It was overwhelming.

During that magical fortnight we’d stay up until the early fog met the morning sun. It was bliss. I was in love with everything. In love with the damp cold air burning ice into our lungs. In love with the upturned umbrellas shoved angrily into bins. In love with the boy who held my hand and kissed me in public. How would I ever leave? Yet our idyll was fast coming to an end. We clung together, crying until our eyes were raw, not knowing when we would see each other again.

By saving money and travelling back and forth across the Atlantic, Steven got to experience my family and life in America while I continued going to school. And then, in 2006, I graduated high school and booked a one-way ticket to Ireland. Steven and I married within the year with just two witnesses. It was a simple affair, without a dress or a cake.

I was eager to begin our family but my body refused to cooperate and I was diagnosed with polycystic ovaries. The doctor dismissed me. ‘You’re young. You have time.’ Depressed by my perceived infertility, I wrote blogs and took photos, explored art and photography. I found communities of women online where we shared our creative selves. We became fast friends, these women who took up space without apology; who wrote poetry, took photographs and spoke freely. I began to heal my relationship with my body. It shifted a dynamic within myself and clarified what I wanted to achieve.

The big freeze of 2009 brought snow, ice, and morning sickness. Forty-two weeks later I was induced – fortunate to be allowed to go past my due date – and became a mom for the first time. Like a selkie shedding her pelt and leaving her watery world, just minutes before midnight, with dark hair and searching eyes, my daughter was born.

The maternity and labour wards were a shock to the system, understaffed with overworked nurses and midwives doing their best to meet the needs of new mothers and their babies – it is between the lines that we are all failed. Your baby made it out of your body alive. You are alive. Be grateful. What more do you want?

Mom flew over for those delicate post-partum days, to mother and teach me how to nourish my babe at the breast, to coax my intuition into confidence and to make the stew that would always taste like home. After a month-long babymoon, I clung to her as she put her bags into the car for the airport. I took my daughter to the bed that Mom had been sleeping in and curled up in the scent of her.

Building my life in Ireland had been my dream. Now, as a new mother, I was desperate to belong in my new home place. While my online circles of women sustained me, I craved Irish women to befriend. Facebook groups opened up the world as I sat on my couch, baby at my breast, talking to other mothers around the country. Virtual breastfeeding support groups, baby-wearing groups and pregnancy groups – I learned about the politics of breastfeeding and the history of formula in Ireland and was initiated into the revelation of feminism. I learned how deep-seated misogyny seeped through our societies; how it had an impact on my choices as a woman, as a pregnant woman, as a birthing woman, as a mother. I was so angry.

Fuelled by my new-found hunger for change, I took a bus to the city to join a Galway birth gathering. We talked about the lack of choice to give birth how and where we wanted and discussed the rising intervention statistics: inductions, caesarean sections, instrumental deliveries, episiotomies. Around a kitchen table with children crawling underfoot and babies asleep in slings, we proposed ways in which we might improve local maternity services. I wanted to know everything.

I became pregnant for the second time, securing a home birth community midwife with the intention to stay away from the traditional maternity system.

Article 40.3.3 of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution states:

The State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal [my italics] right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.

Section 7.7.1: Because of the Constitutional provisions on the right to life of the unborn [Article 40.3.3] there is significant legal uncertainty regarding a pregnant woman’s right to [consent].

Savita Halappanavar and I were both seventeen weeks pregnant when she died in University Hospital Galway on 28 October 2012 at the age of 31 from septic shock following what was diagnosed as an ‘inevitable miscarriage’. Savita attended the hospital because of back pain, where she was advised physiotherapy and sent home. She returned to the hospital hours later with more pain. A foetal heartbeat was detected and blood tests later showed key signals of the risks of sepsis infection. However, the blood test results were not followed up at the time.

In the night her waters broke and she was told about the risk of infection. A scan showed the presence of a foetal heartbeat. Savita asked if there was any way to save the baby and was told it was not possible. ‘Inevitable miscarriage’ is recorded on her medical notes. Aware that her baby would not survive, Savita asked her obstetrician for a termination. She was told that in Ireland it was not legal to terminate a pregnancy on the grounds of poor prognosis for the foetus, and as her life was not currently at risk it was not legally possible to carry out a termination. Savita was given antibiotics to guard against infection. Communication broke down between all medical staff; information on Savita’s health was not passed on. It was noted that she had failed to be monitored as often as hospital policy states. The obstetrician decided to carry out a termination, as it was now clear that Savita’s life was at risk. Her condition deteriorated in theatre after the spontaneous birth of her dead baby, and she was moved to the high-dependency unit, where lifesaving measures continued and ultimately failed.

The baby that could never survive outside of the womb took precedence over Savita’s own health. Savita Halappanavar died because the Constitution denied her rights to make healthcare decisions in pregnancy under the Eighth Amendment. Combined with an overcrowded and understaffed health service, Savita was failed on multiple levels, resulting in her tragic death.

*

I stood in the cold dark November rain at the first vigil in Galway city, staring at Savita’s photo. My own baby tumbled within me as I cried, knowing how easily this could be me or any one of us. Candles flickered. There was a moment of silence. How can this have happened?

The awareness of my own mortality in pregnancy and the superstitions of trading one life for another had become an obsession. In February 2013, when I was 37 weeks pregnant, my 52-year-old dad suffered a heart attack, which required invasive open-heart surgery. As my due date approached and passed, I became certain that Dad would die when I gave birth to this baby. My anxiety only eased when Dad – released from hospital and signed off for travel – and Mom boarded a flight to Ireland. It was as if everything within me was waiting until Dad was safe and well before I could allow myself to give birth. The night of their arrival a babe came spiralling through my pelvis, velveteen head in the caul at my fingertips. My Pisces boy was born in my living room. Dad did not die. The spell was broken.

I updated my bio: Artist and mother of two. My online community became all the more important. Baby in sling, toddler in hand, I took buses across the country to sit at kitchen tables and solve the world’s problems with other women. I ignored the heavier feelings that left me drained. I took herbal remedies and supplements and went to yoga. I had a supportive husband, an empowering birth and I loved being a mom. Post-partum depression can’t happen to me. Yet I couldn’t write or paint my way out of it. I was so tired. Situational depression, I told myself. Motherhood is inherently lonely, I decided. And then Mom lost her job, they lost their home, and Dad was diagnosed with early-onset dementia.

*

I sit on the stairs, pregnancy test in one hand, phone in the other, calling a community midwife while staring at the two solid lines in the little plastic window. What the fuck are you doing? You already have two kids. I don’t know why I’m shocked. We hadn’t used birth control: how ironic, given our infertility years, that I could become pregnant by accident. When Steven gets home we talk about how we’ll figure out a way to make this work. Abortion never crosses my mind. I consider how I might miscarry, a thought that fills me with guilt. Days later I start bleeding.

The early pregnancy unit confirms a strong healthy heartbeat despite the blood telling me otherwise. The relief surprises me. I look at the screen. I want that little blob. Each bleed brings me back to the hospital for another scan and the reassurance of a growing babe. We celebrate Christmas and ring in the New Year. I’m out of the ‘danger zone’, society’s magical twelve-week milestone after which the gestation can be revealed to the rest of the world. Excitement replaces fear at the thirteen-week scan to see that the blob and its heartbeat has grown legs and is bouncing around.

Two days later I toss and turn in my sleep, woken by my own whimpers, my body convulsing with cramps. I google ‘pregnancy symptoms at the end of the first trimester’. Could it be round ligament pain? I stay in bed with a migraine, shivering with cold. I can’t warm up. When the thermometer climbs to 39.4°C, I know something isn’t right. I wrap up in a robe, put a bucket in front of me and close my eyes. Steven and the kids squeeze into the back of my mother-in-law’s car and she drives us all in the dark to the hospital.

In triage I’m brought back to an isolation room to rule out meningitis. ‘Why are you still breastfeeding your two-year-old?’ ‘How much longer are you planning on doing that for?’ ‘He doesn’t need it. He’s old enough.’ I beg for pain relief, writhing in the bed, vomiting into cardboard kidney dishes until there’s nothing left. I will be admitted to the ward for the night as a precaution. In the car park, the kids are asleep in the car. I send Steven home to get some rest.

‘Sorry,’ I call to the nurse, ‘I think I wet myself – I just felt a gush down my legs.’ We pull back the makeshift blanket of my dressing gown to discover the blood pouring from between my thighs.

‘Not to worry!’ the nurse trills. ‘Let’s just get you to sit on this pot so we can measure how much blood you’re losing.’

As she helps me to stand, I can’t stop the river. ‘I’m so sorry! Oh god, I’m so sorry!’ I apologise over and over again, trying to hold it in, trying not to make a mess. The floor, her shoes, her hands; I can’t contain it. Clots escape, thick and black. More people come in to help move me back to the bed and to pull the soaked pyjamas off my legs.

‘How long ago did you last eat or drink?’ a doctor yells at me. Everything is moving fast forward but in slow motion. A primal bellow escapes from my throat, I recognise it as labour. I’m losing my baby. I’ve made it happen.

‘Is your husband here? You need to call him – he has to come back.’ Thick needles pierce my veins as I’m prepped for theatre as fast as possible. So many hands touching and pulling at me, asking questions, giving orders, moving quickly. A nurse presses my phone into my hand. I call Steven and leave a message, telling him that I’m going in for surgery. ‘I love you,’ I tell him. What if I die? I think.

As the bed is pushed through double doors and down the hallway, I watch the ceiling tiles and lights above my head and I pray. I pray that they won’t do a scan and find a heartbeat. I think about Savita as they push the bed into the elevator. Please stop bleeding. Please stop bleeding. Please stop bleeding. They can take my uterus; I have two healthy kids at home. Please stop bleeding.

I wake to a warm hand holding mine.

‘Erin?’

I’m in a hospital bed, in a gown, wearing mesh underwear packed with thick pads as Rebecca, my midwife, tells me that the baby I’ve lost was a boy. It’s over, and I am relieved. And there is grief. Two nights of IV antibiotics. The chaplain brings me a little white box. Inside it, a tiny foetus I had seen bouncing on a screen just days before. I’ve made it happen.

Steven digs a hole in the garden as the January rain falls. Snowdrops dot the ground. I kneel and bury my hands in the soil, placing the babe I’ve wrapped in flower petals and silk into the tiny grave, baptising him with my tears and offering the earth around him seeds to nourish into life. I am a wild and wounded animal. From inside the house, a small voice calls for toast. I weep and we move on. This is women’s work.

The notes I have requested from the hospital arrive, written evidence of the infection that had not been looked for nor diagnosed on previous hospital visits. I think about Savita. Had she received the healthcare she needed, she would still be alive. The baby I’d held in my palm was no more valuable than my own life. Of course he would have been loved, and I mourn for him, but he was not equal to me, nor equal to my other children. My children need their mother. My husband needs his wife. I need my life.

Spring arrives and seasonal hayfever sends me to the doctor. The moment she asks me how I am doing, I break down in tears. It all comes tumbling out: the undiagnosed post-partum depression, the surprise pregnancy, the anxiety about my parents, the miscarriage, the mothering being lonely as hell. She looks at me with gentle concern. I accept the prescription, feeling that my shame about taking antidepressants probably means I need them more than I think. I write about my miscarriage, about the duality of grief and relief, of not being ready to be a mother again and of the intrinsic sadness of losing a baby.

Miscarriage. A word that garners visible pity. And then the reasoning: the higher plan, the at least you have kids, the you can try again. My mom had an abortion and when I miscarried she blamed herself, as if the act of self-survival would one day punish her future daughter. Karma: trading one woman’s abortion for another’s miscarriage. My loss – a statistic, the one in four pregnancies that ends in miscarriage – became a personal responsibility and deal of fate. Yet loss gave me understanding and empathy and the taboo of miscarriage connected me to women around the world. It felt like a rite of passage in the experience of being a human, of being a fertile woman. I was safe, others were not. I have to do something.

*

While I was training as a doula – to become more involved in birth activism and to root myself into the community – the virtual circles remained a treasured resource. Monthly gatherings left me inspired and determined that we could change the world together. Later, the antidepressants help pull me out of the fog. I stop taking them. A few months later, I call Rebecca. Another baby will be joining our family. This time we are ready, but the familiar anxiety comes back to haunt me. What if my dad dies during this pregnancy?

Thirteen weeks pregnant, I travel to the States on my own, visiting my family for Thanksgiving. Though Dad’s dementia is upsetting, there is much to be positive about. My parents are getting back on their feet financially. Things are looking up. Yet I can’t shake off the birth/death paradox that had consumed my second pregnancy. When Dad stands up to greet family arriving through the door, the entire six foot three inches of him comes crashing down, leaving a dent from his head in the wooden coffee table. Mom’s scream pierces the air. My pregnancy becomes an omen.

Dad doesn’t die. We continue on with the festivities, carving the turkey and eating pumpkin pie. When he falls again the night before I’m due to fly back to Ireland, I realise I have no idea how the fuck I’m supposed to manage with the way things are going. Dementia or medication or both take him to a weird land of far away. I miss him. I say goodbye to Dad in the hospital before catching my flight and squeeze him tight. Please don’t die.

Twenty-eight weeks later, a tidal wave crashes within me. Hot salty womb water pours down my shaking thighs. My voice trembles before finding the satisfying hum, the low moan, the vibration of shapeshift. My hands reach under the water, guiding a slip of a babe from one world into the next. I take her to my breast, her dark eyes gazing back at me. She is mysterious and wise, her black hair slicked to a velveteen head. My daughter, my seal pup.

*

Four months after giving birth I venture again to the States, this time with a newborn and two kids. It will be the first meeting of the youngest grandchild. Mom is exhausted. Coming home from work every evening she’d collapse straight into bed before getting up again to play with her grandchildren. It is so unlike her. She books routine blood tests with the family doctor who diagnoses elevated white blood cells – most likely a deficiency. Under the safety of a sleeping house I look up what the numbers are spelling out. I feel sick.

A second opinion sends her to a haematologist. I entertain the kids in the hospital waiting room with stickers and empty water cups. ‘Are these the Irish grandkids?’ The nurse calls us back. Despite having just endured a bone-marrow biopsy, Mom never missed an opportunity to show off and tell the stories of her children to anyone who asked, or didn’t.

Under orders to enjoy the holidays, I curl her hair while she applies makeup.

‘What if I lose my hair?’ In that moment, looking at her face in the mirror, it feels like we both know.

‘You won’t. We don’t know anything yet. Besides, there are so many different types of treatment these days. If you lose your hair, I’ll shave mine off too.’

I won’t allow myself to believe any of the potentials the doctors are looking to rule out. It won’t be talked about today, not with extended family, not just yet. Loading up the truck with kids, we drive two hours south to Granny’s, where we’re joined by my brothers and their families for Thanksgiving. Pies and casserole dishes, stuffing and sweet potatoes.

The TV blares while the little cousins run around after each other. Dad’s dementia is the main focus of conversation – what doctor’s appointments are coming up, what medication is helping. I watch him zoning in and out. I watch Mom trying to make it through the day without falling asleep. I text Steven all of the gossip. I wish you were here. It’s taking everything within me to not say something. I wonder if he really voted for Trump?! I eat pie and explain to Granny again how we don’t have Thanks-giving in Ireland.