Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

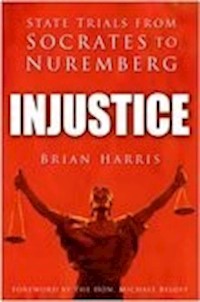

To a lawyer, injustice is the unfair conduct of a trial. This book looks into several notorious cases of supposed injustice: Socrates, Joan of Arc, Charles I, Admiral Byng, Lord Haw-Haw, and the Nuremberg Trials. It looks for answers to the legal question 'was the trial fair?', and the humane question 'was the accused guilty or innocent?'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 524

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

INJUSTICE

INJUSTICE

STATE TRIALS FROM

SOCRATESTO

NUREMBERG

BRIAN HARRIS

FOREWORD BY THE HON. MICHAEL BELOFF

First published in the United Kingdom in 2006 by

Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Brian Harris, 2006, 2013

The right of Brian Harris to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9567 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

For Neil and JaneNo one could want better

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part One: The Traitors

Introduction

1 The Divine Ruler: The Trial of Charles I, 1649

2 The Diarist: The Trial of Sir Roger Casement, 1916

3 The Broadcaster: The Trial of William Joyce, 1946

4 The Atom Spies: The Trial of the Rosenbergs, 1951

Part Two: The Ungodly

Introduction

5 The Maid: The Trial of Joan of Arc, 1431

6 The Starry Messenger: The Trial of Galileo, 1633

Part Three: The Clash of Arms

Introduction

7 The Scapegoat: The Trial of Admiral Byng, 1757

8 The Assassins: The Trial of the Lincoln Conspirators, 1865

9 The Nazis: The Nuremberg Trials, 1945

Part Four: The Disaffected

Introduction

10 The Gadfly: The Trial of Socrates, 399 BC

11 The Good Servant: The Trial of Sir Thomas More, 1535

12 The Martyrs: The Trial of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, 1834

13 The Anarchists: The Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, 1921

Notes

Select Bibliography

Foreword

Justice is both the father and the son of the law. The law’s substance is – or should be – informed by a sense of justice: the law’s procedures should produce a just outcome. Brian Harris’s absorbing book is about cases when very diverse legal systems have – or may have – produced the wrong result; the conviction of the innocent or, at any rate, of those about whose guilt a reasonable doubt exists.

The author has trawled history with discrimination for some of the most famous perceived miscarriages of justice from the trial of Socrates in fourth-century bc Athens to that of the Rosenbergs in twentieth-century ad United States. His subtitle ‘State Trials’ does not bear its conventional sense. For him, state trials are the machinery that the state uses (or, in respect of the Nuremberg trials, a collection of states use) in self-defence against perceived threats to its (or their) authority. And he dissolves the boundary between Church and State to embrace the trials of Galileo and Joan of Arc.

Brian Harris’s achievement is to sweeten his research with a relaxed and readable style. He provides vivid sketches of the characters who people his narrative – the Lincoln conspirators, the Nazi war criminals; and acutely analyses the psychology of such disparate martyrs to their causes as Sir Thomas More and Sir Roger Casement. He conducts a balanced audit of the verdicts reached; and recognises that not all the victims of injustice were necessarily blameless. For every Galileo there was a Lord Haw-Haw too.

Common themes emerge from case histories so distinct in terms of time and context; injustice occurs when the offence charged may be of dubious basis in law, if soundly based in morality. Arguably, the crimes against peace and humanity that were found proven at Nuremberg were offences that did not exist at the time of their alleged commission; treason for which Charles I stood trial should be a crime against a king but not by a king. It occurs when distorted constructions are given to known offences. Both ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ and Sir Roger Casement posed threats to the security of the British nation; the complex issue was whether it was to that nation that they owed allegiance. It occurs when charges are framed in obscure and unspecific terms: a criticism that the author makes of those levelled against Socrates and the Lincoln conspirators. It occurs when the tribunal that determines the case (a military commission in the case of the Lincoln conspirators) lacks constitutional validity or fails the tests now enshrined in the European Convention of independence and impartiality, actual and perceived. It occurs when the punishment does not fit, because it is grossly disproportionate to the crime: as in the case of the Tolpuddle Martyrs or the Rosenbergs.

The book has a theme both perennial and topical. The principle of the common law that it is better that a hundred guilty men go free than that one innocent man is convicted is, in the opinion of many, put at risk at a time when governments, sensitive to populist opinion that sees both results as forms of injustice, dismantle many of the traditional procedural safeguards such as trial by jury or the privilege against self-incrimination. Indeed, the terrorist threat has led many governments to bypass the criminal process altogether and to deprive persons, presumed to be (whatever the actual facts) innocent, partially or wholly of their liberty without any trial at all.

There are, of course, counter trends. The fair trial provisions of the Human Rights Act have been interpreted by a liberal judiciary to mean that no verdict obtained in proceedings conducted in breach of those standards can stand. Whereas in the cases, for example, of Lord Haw-Haw and the Rosenbergs, a single judge stood out in rejecting the claims of the state, in the recent case of the Belmarsh detainees, there was only one Law Lord out of nine who was prepared to support them. Extreme cases may make bad law; but Brian Harris reminds us of the risks of departing from due process, and of blindly accepting that the interests of the state and those of justice necessarily coincide. For this alone it merits a wide and attentive readership, whom it will not disappoint.

Michael Beloff QC

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Alison Cooper of Leicester University, Andrew Carnes and Andrew Tabachnik of 4/5 Gray’s Inn Square, Jack Maurice, barrister and Dr Tom McMorrow for reading the text and correcting its more egregious errors. Nor must I overlook the services of Olney library, whose ability to obtain even the most recondite works suggests a reach almost as extensive as that of the Roman Empire in its prime.

Is not injustice the greatest of all threats of the state?

Plato, The Republic

Introduction

The popular image of the state trial is of a cynical attempt by the authorities to silence an awkward individual at all costs, often with poignantly tragic consequences – and this book contains its fair share of such cases. But state trials are not always like this. In the cold glare of the legal process some accused, though acting from the highest motives, are manifestly guilty; while others, though innocent, prove to have been far from blameless. Even where the trial is flawlessly conducted, the man in the public gallery can be left with the uneasy feeling that justice has not been entirely served, either because the whole truth has not come out or because the line between right and wrong has been imperfectly drawn. With uncertainties and moral ambiguities like these abounding, the state trial can be a fascinating petri dish of human behaviour.

I can – just – remember the fuss at the end of the Second World War when William Joyce, or ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ as he was better known, was hanged for treason. At the time I understood little of the issues at stake and even less about the man at the centre of them, a lack of understanding that I have been able to remedy, in part at least, in preparing this book about state trials and their potential for injustice.

People tend to think of state trials as the trial of a political offence, but few countries have – or are willing to admit to having – political offences. I prefer to think of state trials simply as something that men in power do to people they feel threatened by. An advantage of this approach is that I have been able to include in this book, not only such obvious crimes as treason, espionage and insurrection, but also such diverse matters as inattention to duty, cowardice, robbery for political purposes, impiety and industrial unrest. And, by treating that great supranational institution the Catholic Church as a state, I have been able to take in the worlds of heresy and witchcraft also.

I cannot pretend that my selection of cases is in any sense methodical. I have chosen them, whether famous or relatively unknown, simply because they interested me as examples of real or supposed injustice. This has resulted in a motley cast of defendants, ranging from admiral to actor, royal to rustic, fish peddler to philosopher. Their stories are sometimes horrifying, sometimes ennobling, often both; which is no doubt why such trials have inspired so many works of fiction. But fiction can distort our understanding of events – often the greater the writer the greater the distortion. On examination, the real stories of Joan of Arc, Galileo and Sir Thomas More turn out to be every bit as moving as those that have come from the pens of Bernard Shaw, Bertolt Brecht and Robert Bolt.

Some of these trials disclose a deplorable determination on the prosecutor’s part to secure a conviction by any means; and the prosecutor’s misconduct has sometimes proved to be the judge’s temptation. While most courts try, in the old phrase, to ‘let justice be done though the heavens fall’, we should not allow our proper respect for the law to be carried over into an uncritical acceptance of the courts. Judges are human like the rest of us. The good judges know this and struggle to achieve that dispassionate conduct of the proceedings which their duty demands. Unfortunately, as these pages can testify, not all have been successful. (Of course, jurors can fall into the same trap, but they have a better excuse.)

Conversely, we should not assume that every allegation of ‘injustice’ is well founded. When I looked into a number of notorious cases of supposed injustice I found them to be nothing of the kind. It is, for example, difficult to fault the conviction of the Tolpuddle Martyrs; the injustice in that case was the passing of a sentence wholly disproportionate to the offence. (How that came about is a mystery that I attempt to unravel.) And the convictions of Sir Roger Casement and Lord Haw-Haw proved on examination to be more justifiable than some critics contend. But it is to North America that we must turn for real controversy. Sacco and Vanzetti were two young Italian immigrants who went to the electric chair passionately denying their part in robbery and murder. Three decades later Julius and Ethel Rosenberg suffered the same fate for allegedly passing information about the atomic bomb to Russia. Heated debate still surrounds all four convictions, but I will not anticipate here my conclusions on their fascinating stories.

Anyone trying to understand what went on in the minds of men and women in generations long gone is faced with a question that has to be answered. When we have difficulty in judging the lives and morals of even our own grandparents, how can we expect to judge those who lived and died centuries ago? In fact, while outlooks and assumptions may change with the years, human nature seems to be remarkably consistent. For that reason I believe that we are justified in attempting to understand the lives – and deaths – of people condemned by courts now long forgotten, provided only that two criteria are satisfied: we must be in possession of a credible record of what took place and we must judge the past on its own terms, not ours.

To the student of history, one of the advantages of the courtroom is that its proceedings have long been recorded with care. Take, for example, the judicial murder of Joan of Arc. Without the careful account of a fifteenth-century notary public we would have only the barest outline of this exceptional young woman’s story. And the unbelievably poignant tragedy of Admiral Byng comes down to us from the meticulous report made at the time by an attorney-at-law. I have stretched the ‘credible record’ criterion to its limits in the case of the Greek philosopher Socrates, as will be clear from the third note to that chapter. It has, however, ruled out any discussion of possibly the most intriguing trial of all, that of Jesus of Nazareth.

When it came down to it, I found that my decision to judge trials by the standards of their day and not by those of the twenty-first century was not as limiting as I had imagined. Most injustices proved not to turn on fine points of legal theory, but to be blatant attempts to subvert the court or the judicial process, a wrong that our ancestors had no difficulty at all in recognising, although sometimes quite a lot in preventing.

It is a curious fact that lawyers’ concerns with injustice revolve almost exclusively around the question of whether a trial was conducted fairly or not. The consequence of this somewhat blinkered approach is that a trial can be considered ‘fair’ even though an innocent man has been convicted, and vice versa. The man in the street knows better; for him, a just trial is one that results in the conviction of the guilty or the acquittal of the innocent. Perhaps the time has come to pay more attention to this view?

Despite the great efforts that go into the preparation and conduct of criminal cases, the outcomes seldom satisfy everyone. This is because a trial is not a scientific experiment that can confirm or refute a hypothesis. Underneath the majesty of the law a trial is in fact nothing more than a mechanism – and a very imperfect one at that – designed to provide an agreed version of disputed facts. Viewed in the cold light of history, however, all facts are provisional. That is why I have felt no compunction in offering my own opinion on the guilt or innocence of those unhappy individuals who fill the starring roles in this book. I would be surprised, not to say disappointed, if all my conclusions prove to be acceptable to everyone. I ask only that readers should do what I have tried – no doubt imperfectly – to do: namely, to base their judgements, not on preconceptions and prejudices, but on a dispassionate review of the facts, wherever that might lead.

It is here that I must own up to a glaring omission. It is sometimes overlooked that an injustice occurs whenever a guilty person is acquitted. The verdict of the court is ‘not guilty’, rather than ‘innocent’, and convictions are upset on appeal only on the narrow grounds that they are unsafe or unsatisfactory, not that they were wrong – and that is how it should be. But the consequence of this is that, tabloid headlines notwithstanding, the courts do not ‘clear’ people of crimes; they are simply not equipped to do so. However, since the English law of libel has the capacity to draw blood, it would be a brave commentator who dared to suggest that a living person was guilty of a crime after he had been acquitted or his conviction quashed on appeal. No matter that wrongful acquittals are probably quite common even today, you will look in vain for any examples of them in this book.1

As a lawyer, I was first attracted to the topic of injustice by the legal questions it can pose, and I have certainly dealt with those whenever they have gone to the heart of the matter. Was Admiral Byng shot, for example, because of a misunderstanding of the Articles of War? Were the Tolpuddle Martyrs properly convicted under an Act of Parliament passed for an entirely different purpose? Should the Nazi leaders have been found guilty of offences that did not exist at the time they were committed? Intriguing though these questions are, when I came to examine the records I found that they were in every case overshadowed by the deeply moving human stories involved. I was particularly struck by the way in which even great men can bring about their own downfall. Socrates, for all his nobility of mind and spirit, seems almost to have invited the death sentence that was passed upon him; the misfortunes of the great Galileo were due as much to his own pride as to the machinations of his enemies; and Charles Stuart died, not merely for his belief in the divine right of kings, but also because of a series of bad decisions on his part.

Most of the cases in this book raise profound moral issues, many of which still resonate loudly in today’s world. How far, for example, should society go in tolerating dissent? Can a burning belief in social justice ever justify terrorism? Is a charge of treason an appropriate response to someone who takes up arms to liberate his country? And, perhaps most topical of all, is a nation ever justified in attacking a tyrant who is not directly threatening it?

But the cases also raise a question deeper than any of these, a question that concerns the paradox that can sometimes be found at the heart of man: how can people devoted to humanity in general be so contemptuous of individuals in particular? John Wilkes Booth threw away his life in support of a bad cause already lost. Sacco and Vanzetti embraced a movement committed to indiscriminate murder in order to establish the just society. And the intelligent and socially conscious William Joyce walked to the gallows proclaiming his belief in a cause responsible for more misery than he could bring himself to believe possible. How is it that benevolence and malevolence, greatness and fallibility, bravery and wickedness, can sometimes all be combined in the same person? The stories in this book present a unique opportunity to study this enigma.

PART ONE

The Traitors

Introduction

There is always a temptation for those who come out on top at the end of a bitter conflict to use the courtroom to demonstrate their opponents’ evil ways. These proceedings are usually so far removed from ordinary notions of justice that we describe them as show trials. But show trials sometimes backfire on those who set them up, as was the case with the trial of Charles Stuart.

When Parliament emerged victorious from the English Civil War, all that Oliver Cromwell wanted was for the defeated King to defer to Parliament in financial matters. Believing himself to rule by divine right, Charles did not feel he could concede this without abandoning his duty to God. Though the army fumed, Parliament might have borne even this obduracy had not the King, while ostensibly engaged in negotiations with his former enemies, secretly approached foreign powers with a view to recovering his throne by force. When his double-dealing came to light, the hard-headed, but hitherto tolerant, Cromwell finally snapped. He determined to bring about the King’s death, but with as much of the trappings of legality as he could muster. It might be thought that a modern reader would have no difficulty in deciding where his sympathies lay as between a (more or less) democratically elected Parliament and a man who believed himself to be a divinely anointed ruler, but it is impossible not to admire the courage of the King before a court that he considered, probably correctly, to be lacking in any lawful authority. It was a trial in which legality and nobility inclined one way, brute force and the public will the other. Charles died nobly at the hands of an illegal tribunal, but which of them, ultimately, was in the right?

Ireland has long been a thorn in England’s side, but the story of Sir Roger Casement’s treachery is surely unique. A British consular official who had performed incalculable services for mankind, Casement came to believe that Irish independence justified supporting his country’s enemy in time of war. His feeble attempt at insurrection failed, but his controversial death probably did more for his cause than his life. To forestall any possibility of clemency for the convicted traitor, British Intelligence took a course for which it has since been widely vilified: it leaked to the press documents that appeared to show Casement as a man of depraved character. Nationalist opinion, buttressed perhaps by a degree of homophobia, became convinced that the documents were forged; it is only recently that the full story has come to light.

Casement at least believed in a noble cause. The same could not be said of William Joyce, who in the Second World War famously broadcast for Hitler under the sobriquet Lord Haw-Haw. His trademark, ‘Germany calling, Germany calling’, although threatening at first, came in time to be treated by his listeners with amused contempt. Nevertheless, there was a great deal of unease when at the end of the war he was sentenced to death on what many considered to be a technicality.

Of Casement’s and Joyce’s treasons there can be no doubt, but were the British justified in using Casement’s diaries to blacken his name, and were they right in refusing clemency to Joyce, a man who had long become a figure of fun? Judge for yourself.

The last trial in this section took place in the 1950s when America was in the grip of the twin fears of Russian domination and atomic war. When Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted of ‘giving Russia the secret of the atom bomb’, therefore, it is not surprising that many felt they should suffer the ultimate penalty. Their supporters – not all of them communists – sought to show the couple as the victims of an oppressive government and a corrupt legal system. The facts as they have finally emerged support neither scenario completely. Perhaps more than any other case in this book, that of the Rosenbergs exemplifies the conflicting issues and moral ambiguities that so often surround state trials.

CHAPTER ONE

The Divine Ruler

The Trial of Charles I, 1649

Relations between the English King and his Parliament were at breaking point. Charles I, having so long sidelined his most capable lieutenant, now brought Thomas Wentworth back from Ireland, which he had recently pacified, and made him Earl of Strafford and his chief adviser. He also gave him an assurance ‘on the word of a King’ that, whatever should befall, he would not suffer in life or fortune. But it was too late. Believing that he intended to use Irish troops against his own countrymen, the House of Commons threw Strafford into the Tower of London and began impeachment proceedings against him for treason. Strafford’s formidable defence before his peers forced the Commons to resort to a bill of attainder, a procedure that dispensed with the need for proof of guilt. The bill passed both Houses of Parliament, but Strafford could not be put to death without the King’s warrant. On Good Friday 1641, believing that he could still save his faithful servant, the King wrote to Strafford renewing his promise of protection; he had not reckoned with the strength of feeling in the country. The judges and the Church advised Charles that he had no option but to sign the warrant and Strafford generously released Charles from his promise. The King ruefully commented, ‘My Lord of Strafford’s condition is happier than mine’ and on a sunny day in May 1641 the head of the King’s first minister was struck from his body at Tower Hill. Eight years later Charles had occasion bitterly to regret his betrayal of the only man who, had he been called for earlier, might have saved him.

The English Civil War had many causes, chief among them religion and taxation. Puritanism – the idea that people did not need the clergy to mediate between them and their God – had taken firm hold in England during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, particularly among the ‘lower’ classes. It was anathema to England’s religiously conservative King and his Catholic wife, Henrietta Maria, and the response was a series of increasingly repressive measures designed to secure conformity. It alienated large chunks of society. (In Scotland it even led to war.) But it was not only religion that led to unrest.

Charles had inherited from his father, James, a system under which the king had all the responsibilities of government without the power to raise the funds necessary to discharge them. Parliament held the purse strings and the king was forced to resort to various stratagems to circumvent its wishes. In 1628 Charles had reluctantly accepted a Petition of Right outlawing non-parliamentary taxes and arbitrary imprisonment, but it was not to last; the following year he dismissed Parliament and attempted to rule solely by virtue of the royal prerogative. The ensuing Eleven Years’ Tyranny, as it came to be called, was a deep affront to a people accustomed to seeing their laws approved by their representatives from the shires.

In the end, lack of funds forced Charles to call another Parliament. It promptly declared the widely resented ‘ship money’ illegal,1 abolished the unpopular court of Star Chamber and voted to support the Scots; everything, in other words, except provide the taxes necessary to run the country. A Catholic revolt in Ireland now prompted the parliamentary leader John Pym to organise what was known as the Grand Remonstrance. After listing Parliament’s grievances, which it blamed on the King’s popish advisers, the Remonstrance demanded that the King should employ only those whom Parliament ‘may have cause to confide in’. Meanwhile, Pym and four other Members of Parliament were planning to impeach the Queen. Her crime? Attempting to enlist foreign aid against her own subjects.

Charles decided to make a stand. On 4 January 1642 he went to the Commons in an attempt to arrest the five awkward Members. As he entered the Chamber the door was left open so that Members could see his escort aiming their pistols at them. But firmness is effective only when it works and Charles had not laid his plans well. The five Members, who had had warning of his approach, had already left by the back door. Doffing his hat, Charles said, ‘Mr Speaker, I must for a time make bold with your chair’. When he asked the assembly whether the five were present, the King was met with silence. When asked directly, Mr Speaker Lenthill memorably replied, ‘Sire, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me.’ As he left the Chamber empty-handed, the King wryly observed ‘all my birds are flown’. From high drama his mission had turned into low farce. With popular opinion in London now firmly against him, the King felt compelled to leave town, first for Hampton Court and then for Windsor.

WAR

Rumours now began to circulate of a royal attack on London, and barricades were thrown up in the streets. Parliament issued an ordinance raising the militia; Charles’s attempt to forbid it was ignored. Conflict was now inevitable, and on 22 August the King raised his standard at Nottingham. It was an inauspicious beginning to a military campaign: last-minute alterations to the text led to the proclamation being garbled by the herald, and the standard blew down in the wind.

The first major engagement was the inconclusive battle of Edgehill (23 October 1642). After that, fortunes swung from one side to the other until in 1645 the Parliamentarian generals Cromwell and Fairfax created the formidable New Model Army. Their efforts were to bear fruit in the decisive Parliamentary victory of Naseby (14 June 1645). The last Royalist force surrendered at Stow-on-the-Wold in March the following year. Charles, hoping to avoid falling into Parliamentary hands, disguised himself as a servant, fled to Newark and surrendered to the Scots. Although there were more battles, the King’s cause was now lost. As with all civil wars, families had been split in their loyalties, with brother pitted against brother. The conflict was made all the more bitter by pamphleteering that graphically exaggerated the atrocities which violent hotheads on both sides sometimes perpetrated on their defeated opponents. All in all, nearly 800,000 people had died throughout the British Isles, directly or indirectly, as a result of the war, proportionately more than in the bloodbath that was to be the First World War of 1914–18.

The end of the war had not put an end to popular discontent, but this time it was combined with a new radicalism. The Parliamentary army, which had gone for many months without being paid, was concerned that all its sacrifices should not go in vain. Some regiments elected four of their number (known as ‘agitators’) to represent their views to the leadership, a system that was eventually embodied in the army structure. At the same time a loose populist movement called the Levellers was active among them. Its manifesto, The Agreement of the People, made a number of proposals well in advance of their time, including universal franchise and parliamentary constituencies based on population. (The movement proved to be an embarrassment to the generals and was put down by force in 1649.)

This new-found radicalism led to what was perhaps the most extraordinary political event of the war. From 28 October to 1 November 1647 in the chancel of St Mary the Virgin Church, Putney, Cromwell chaired a series of meetings between all strands of opinion in the army. To read the shorthand account of the Putney debates is to witness the first rehearsal of that great disputation between authority and the individual that the Western world has been engaged in ever since. It was during these discussions that Colonel Rainsborough, soon to be murdered by Royalists, memorably declared: ‘I think that the poorest he that is in England has a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore truly, sir, I think it’s clear that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government.’2 Ultimately, it proved impossible to reconcile all the conflicting opinions, and Cromwell dissolved the meeting before it got out of hand.

Meanwhile, the Scots, having sought unsuccessfully to persuade Charles to introduce Presbyterianism into England, effectively sold him to Parliament for £400,000 arrears of pay. The King’s correspondence captured at Naseby had revealed how he had been plotting to offer concessions to Catholics in exchange for military aid. It was published within a month. Nothing could have upset the army more. One day, a troop of horse under the command of a cornet,3 Joyce, arrived at Holdenby Hall in Northamptonshire, where the King was detained, for the purpose of removing him to a more secure place. Asked by what authority he was acting, Joyce indicated the soldiers behind him, saying: ‘There is my commission.’ Charles ruefully admitted: ‘It is written in characters fair and legible enough.’4 He was taken to Newmarket and thence to Hampton Court Palace in what was far from close confinement. Despite the fact that he was engaged in negotiations with Parliament, he foolishly escaped, as he claimed, ‘for feare of being murder’d privatly [sic]’.5 Without any clear plan of action, the King ended up in the Isle of Wight, whose Parliamentary governor he believed to be sympathetic to his cause.

WAR REIGNITES

Lodged comfortably at Carisbrooke Castle, the King resumed negotiations with Parliament. Behind their backs, however, he swallowed his pride and secretly agreed to introduce Presbyterianism into England in exchange for a Scottish army. With this agreement under his belt the King felt able to reject Parliament’s terms, unaware that his duplicity had been revealed to Cromwell. As the Parliamentary commander Henry Ireton remarked, he ‘sought to regain by art what he had lost in fight’. Matters now took a serious turn for the worse, provoked almost certainly by royal intrigue. In March 1648 uprisings took place in Wales that quickly spread to other parts of the country. In July the Scots invaded England. Order was swiftly restored, but only after a great expenditure in effort and blood. The Second Civil War, as it is called, was characterised by even greater acts of brutality on both sides, which only served to harden the resolve of those calling for extreme measures. But even at this late date Parliament still sought an accommodation with the King, the so-called Treaty of Newport. While these negotiations were going on, the now paroled Charles was secretly planning to escape.

The rift between Parliament, which wanted to continue talking with the King, and its impatient army now became wider. At the beginning of the war there had been no thought of deposing the King, let alone of his execution, but in November Parliament was presented with a ‘Remonstrance of the Army’ that called for the King to be put on trial. Even at this eleventh hour a council of officers sought an accommodation with the King. But Charles rejected their proposals and was removed to the more secure Hurst Castle on the Solent and thence to Windsor Castle, while London was garrisoned by the army. When Parliament voted to continue negotiations, 150 of its Members were forcibly turned away from its doors in an action that came to be known as Pride’s Purge after the army colonel who undertook it.

Cromwell, who had not until then been directly involved in the discussions with the King, made one last effort to reach an agreement. He sought no more than what we would call a constitutional monarchy, but when the King refused even to see his representative Cromwell angrily commented: ‘I tell you we will cut off his head with the crown on it.’6 What manner of man was this king who could thus reject his only hope of survival?

CHARLES THE MAN

Charles was a second son, becoming heir to the throne only on the death of his charismatic elder brother, Henry, whom he had adored. Charles himself was short, suffered from a slight stammer and tended to keep his own company.

A loving husband and devoted father, Charles pursued interests in art and in the field. Disarmingly courteous even to the humblest, he did little to seek popularity. ‘Princes’, he once told the House of Lords, ‘are not bound to give account of their actions but to God alone’. In the words of the historian C.V. Wedgwood, this slight, reserved man ‘neither solicited nor gained the affection of his people from whom he expected neither more nor less than duty’.7 Throughout his life the King had no doubts about the place of the monarch in God’s plan. His father James had taught him that a good king had ‘received from God a burden of government whereof he must be accountable’.8 A king, in other words, ruled by divine right; his powers and duties were not temporal and could not be removed by man. In battle there was no question of the King’s personal bravery, but he had little skill or interest in the art of government, which, combined with a dogmatic sense of divine mission and a naturally devious nature, was to prove his undoing.

Oliver Cromwell had his own understanding of the divine will and now turned all the force of his formidable personality to the task of bringing the King to trial. It was a narrow thing; the decision to set up a High Court of Justice to try the King scraped through the Commons by only 26 votes to 20. When the House of Lords refused its consent, the Commons decided to go ahead without it. Any attempt at impartiality was abandoned at the outset by the Act of Commons setting up the court, which charged that

Whereas it is notorious that Charles Stuart, the now King of England … not content with the many encroachments which his predecessors had made upon the people in their rights and freedoms, hath had a wicked design totally to subvert the ancient and fundamental laws and liberties of this nation, and in their place introduce an arbitrary and tyrannical government, and that besides all other evil ways and means to bring this design to pass he hath prosecuted it with fire and sword …9

Well over a century before the American Declaration of Independence, the Act proclaimed the revolutionary doctrine that

the people are, under God, the original of all just power … That the Commons of England … representing the people have the supreme power in this nation … whatever is enacted, or declared for law, by the Commons … hath the force of law … although the consent and concurrence of King, or House of Peers, be not had thereunto.

There were 135 commissioners appointed to the court, including some of the chief officers of the army, landed gentry and City aldermen. The two chief justices (of the King’s Bench and Common Pleas) and the lord chief baron refused to preside, ostensibly on the ground that the trial contravened the principle that all justice flowed from the king. In the end the presidency went to a reluctant Welsh judge, the little-known John Bradshaw. A barrister, John Cook, was appointed Solicitor-General and joint prosecutor, becoming sole prosecutor when his leader fell out.10

A Dutch scholar, Isaac Dorislaus, was brought in to assist in drafting the indictment, for which there was no precedent in England. It alleged that Charles

trusted with a limited power to govern by and according to the laws of the land, and not otherwise … out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people … he, the said Charles Stuart … hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented … [and] hath caused and procured many thousands of the free people of this nation to be slain …

All which wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation, by and from whom he was entrusted as aforesaid.

By all which it appeareth that the said Charles Stuart hath been, and is the occasioner, author, and continuer of the said unnatural, cruel and bloody wars; and therein guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby.11

‘NOT AN ORDINARY PRISONER’

The trial began on the afternoon of Saturday 20 January 1649 in the south end of a crowded Westminster Hall, where the law courts customarily sat.12 In the event, only 68 of the 135 commissioners turned up. When the name of Fairfax was called, his wife shouted from an upstairs window: ‘Not here. He has more wit than to be here.’

The judges sat at a table covered by a rich Turkey carpet, on which was placed the sword and mace. Lord President Bradshaw, flanked by two lawyers, sat in a chair raised above the rest wearing an iron-reinforced hat in fear of assassination. Armed men were stationed on the roofs and the cellars were searched.

The King was brought in by the Serjeant at Arms and took his seat on a chair upholstered in crimson velvet facing his judges. He was dressed in black and wore the silver Star of the Garter. Around his neck was the blue ribbon and jewelled George of the Order, a locket that contained a miniature portrait of his wife.13 He refused to acknowledge the court, declining even to remove his broad-brimmed hat. His composure was disturbed, however, by a trivial incident at the outset of the proceedings. When the prosecutor Cook began to speak, Charles, seeking to interrupt, tapped him on the shoulder two or three times with his cane, causing its silver head to fall off. The King looked round but, finding no one willing to pick it up, did so himself. Some saw the incident as symbolic of his reduced circumstances.

The reading of the indictment was the first time that the King had been made aware of the accusations against him and he laughed at the reference to himself as ‘tyrant’ and ‘traitor’. When asked to plead guilty or not guilty, Charles demanded to know

by what power I am called hither … by what Authority, I mean, lawful; there are many unlawful Authorities in the world, Thieves and Robbers by the highways: but I would know by what Authority I was brought from thence, and carried from place to place, (and I know not what), and when I know what lawful Authority, I shall answer: Remember, I am your King, your lawful King and what sins you bring upon your heads and the judgement of God upon this land, think well upon it – I say think well upon it – before you go from one sin to a greater. Therefore let me know by what lawful Authority I am seated here and I shall not be unwilling to answer. In the meantime I shall not betray my trust. I have a trust committed to me by God, by old and lawful descent. I will not betray it to answer to a new unlawful Authority.

This was not the answer that the judges wanted to hear. Bradshaw asked the King once more ‘in the name of the people’ to answer to the charge, adding inadvisably, ‘of which you are elected King’. Charles promptly corrected him: ‘England was never an elected kingdom, but a hereditary kingdom for these thousand years …’. He went on to challenge the court directly:

I do stand as much for the privilege of the House of Commons, rightly understood, as any man here whatsoever. I see no House of Lords, here that may constitute a Parliament, and [the King too] should have been. Is this the bringing of the King to his Parliament? Is this the bringing an end to the Treaty in the public Faith of the world? Let me see a legal Authority warranted by the Word of God, the Scriptures, or warranted by the Constitutions of the Kingdom, and I will answer …

The King spoke confidently and without any sign of his usual slight speech impediment. The court, unsettled by his robust defence, retired to consider what to do. As they left the hall, the soldiers, seemingly acting under orders, shouted, ‘Justice, Justice’. Nevertheless, the King had had the better of the first day’s proceedings.

Next day, the commissioners met privately in the Painted Chamber of the Palace of Westminster to decide how to deal with the problem of the King’s refusal to plead. Should he persist in it, they concluded, it should be treated as an admission of guilt. After they had filed back into court, Bradshaw announced that they were ‘satisfied fully’ with their authority and that the King was required to answer to the charge. Charles continued to challenge the authority of the court. ‘A King cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth.’ When Bradshaw insisted on a direct answer, the King replied,

I do not know the forms of law; I do know law and reason, though I am no lawyer professed: but I know as much law as any gentleman in England, and therefore, under favour, I do plead for the liberties of the people of England more than you do; and therefore if I should impose a belief upon any man without reasons given for it, it were unreasonable.

He again required to know how the Commons, that is to say, the Commons alone without the Lords, had become a court of judicature. Told that it was not for prisoners to ‘require’, he responded bitterly: ‘Sir, I am not an ordinary prisoner.’

The trial now went into its third day, still with no plea from the accused. When Bradshaw foolishly told the King that he was ‘before a court of justice’, Charles contemptuously replied: ‘I find I am before a power.’ Offered the opportunity to speak in return for a plea, the King replied,

For the charge, I value it not a rush. It is the liberty of the People of England I stand for. For me to acknowledge a new court, that I never heard of before, I that am your King, that should be an example to all the people of England, to uphold justice, to maintain the old laws, indeed I do not know how to do it.

For the next two days the court sat in private and without the prisoner in order to hear the depositions of thirty-three witnesses concerning the behaviour of the Royalist forces in the field and the King’s personal responsibility for it. By now, the commissioners’ attendance had dropped to forty-six. At the end of this session the court ordered the preparation of a draft sentence, omitting only the form of execution. The omission was remedied the following day.

When the court met for the last time, on Saturday 27 January, cries of ‘Justice’ and ‘Execution’ were heard in the hall, no doubt as carefully orchestrated as those of the previous days. Charles asked to address the Parliament but was refused. At this point, Downey, one of the commissioners, publicly broke ranks and asked to speak against the sentence. The court promptly retired. After he had been reminded of his duty by Cromwell (one may imagine how forcibly), the hearing resumed. Bradshaw, dressed for the first time in scarlet robes, now began his address to the prisoner. As he started to speak, a masked woman cried out in objection: ‘Cromwell is a traitor.’ It was the indomitable Lady Fairfax once again. Bradshaw’s peroration was a long one and after it was finished, the clerk of the court read out the sentence of death. The King was dismayed to realise that this had happened without his having been given another opportunity to address the court: ‘I am not suffered to speak! Expect what justice other people will have!’ As he was bustled out of the hall the soldiers scoffed at him and puffed smoke in his face; one even spat at him. Charles was heard to remark: ‘Poor creatures. For a sixpence they would say as much of their own commanders.’ The execution was to take place in three days’ time.

Within forty-eight hours the warrant for Charles’s execution was signed, but only by 59 of the 135 commissioners, 8 of them Cromwell’s relatives. Some were later to claim that he had bullied them into submission. (Cromwell is said to have held the hand of one and forced him to sign.) Nevertheless, nine of those who had been present at the sentence failed to sign the warrant.

‘THE BRIGHT EXECUTION AXE’

Charles, who had hitherto been lodged in a private house, was now taken to St James’s Palace, perhaps in order to spare him the sound of the scaffold being built outside Inigo Jones’s great Banqueting House in Whitehall, at where the execution was to take place. Two musketeers were stationed in his bedchamber all night and he got little sleep. (This indignity was removed after the first night.) Allowed to see his two youngest children, Charles commanded them to forgive his enemies but not to trust them. In an attempt to save his father’s life, the Prince of Wales sent the Commons a blank sheet of paper with his signature at the foot. The Dutch ambassadors also sought to intervene. It was all in vain; the Commons now sent for ‘the bright execution axe’.

It was a cold morning on the day of the execution and Charles asked for ‘a shirt more than ordinary by reason the season is so sharp, which some will imagine proceeds from fear’.14 He was attended by the Bishop of London, William Juxon, who read chapter 27 of St Matthew’s Gospel, the trial and execution of Jesus. Asked by the King whether he had chosen this specially, Juxon explained that it was the reading prescribed for the day. At about ten o’clock the King was taken across the park accompanied by a guard of halberdiers marching to the beat of drums, but a delay in the arrangements meant that the execution could not take place until nearly two o’clock in the afternoon. When all was ready, the King, wearing the Star of the Garter, walked through the Banqueting Hall with its splendidly decorated Rubens ceiling and stepped out of a specially enlarged window onto the scaffold. The first people he must have seen there were two grotesquely disguised headsmen, ready, should the King resist, to fasten him to staples driven into the scaffold. (Their identities were to remain a closely guarded secret.)

Charles made a brief speech to the crowd, saying that he had ‘forgiven all the world, and even those in particular that have been the chief causes of my death’.15 He had made his confession and received absolution and was in a state of grace, but he could not resist protesting his innocence for the last time: Parliament had started the war, not him. He desired the liberty and freedom of the people, which even at the end he declared was his responsibility, not the people’s. Referring to the fate of his faithful servant Strafford, he said: ‘An unjust sentence that I suffered for to take effect is punished now by an unjust sentence upon me.’ When the executioner inadvertently touched the axe with his foot, Charles broke off to remark, ‘hurt not the axe, that may hurt me’. Almost his last words were: ‘I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.’ (The language was from Corinthians via Bishop Juxon.) Few could have heard his words; the public had been kept well back behind a mass of soldiers.

Tidying his long hair under his cap, Charles arranged himself on the low block. When he stretched out his arms to indicate that he was ready, the executioner severed his head from his body with a single stroke. A young lad in the crowd later recalled that they gave ‘such a groan as I have never heard before and desire I may never hear again’.16

A week later the monarchy was abolished and replaced by the Commonwealth, which in turn was replaced by the Protectorate in 1653. Though restored briefly following the death of Cromwell, the Commonwealth proved unable to survive. Two years later a commission was sent to Holland instructed to bring the late King’s son back to his realm. With the Bill of Rights of 1689 England began to evolve into the constitutional monarchy that Charles I had refused to contemplate.

THE FATE OF THE REGICIDES

Charles II was wisely magnanimous towards his father’s enemies, but about a hundred men who had been closely involved in the execution of the King were specifically exempted from the Act of Pardon. Of these, most were in fact pardoned, particularly if they had surrendered to justice. Twenty-nine were put on trial before a court set up for the purpose. They received more justice than the late King. In the end only ten were executed as traitors in the usual barbarous way (the prosecutor John Cook was one of them), and the rest were imprisoned for life. An equestrian statue of Charles now stands in Whitehall near the spot where they suffered their horrible deaths. Two years later three of the regicides who had fled abroad were extradited, tried and executed. Yet more were privily killed, the unfortunate lawyer Isaac Dorislaus among them.

Some were not to escape even after death. Cromwell, his son-in-law, Ireton, John Bradshaw, the president of the court, and Colonel Pride had all died before the Restoration. They were nevertheless tried posthumously for high treason, after which their bodies were exhumed and hung on the gallows at Tyburn (now Marble Arch). Time gives a better perspective, and a statue of Cromwell now stands outside Westminster Hall, the site of England’s most famous trial.

But did Charles get a fair trial?

WHO WAS IN THE RIGHT?

The judgment of the court that Bradshaw had read out was a curious mixture of historical inaccuracies and legal truisms. In summary and stripped of the flowery language of the seventeenth century, it alleged that:

• the King is subject to the law;

• by his actions Charles had put himself above the law;

• the people of England had chosen their form of government;

• while ‘the King had no equal within the realm’, he was ‘the lesser within the whole’;

• the barons of old had stood up to King John for the people;

• today, the Parliament is doing the same;

• Parliaments were ordained to redress the grievances of the people;

• the King had refused to call a Parliament;

• kings have been called to account in the past (Edward II and Richard II were particularly mentioned);

• as ‘protection entails subjection’, so ‘subjection entails protection’;

• the King had been a ‘tyrant, traitor, murderer and a public enemy’.

Charles’s written defence,17 which he had been denied the opportunity of reading out in court but which was published after his trial, argued that:

• a prosecution may be warranted only by God’s laws or the municipal laws of the country (i.e. English law);

• the Old and New Testaments demand obedience to kings;

• English law states that the king can do no wrong;

• the House of Commons, acting alone and without the House of Lords, has no authority to set up a court;

• the authority of the Commons had been diminished by the forcible exclusion of so many of its Members;

• the Commons had no popular mandate (to use a modern expression) for trying the King;

• by doing so without authority the Commons was violating the privileges of both Houses of Parliament, as well as the liberties of the people;

• it was a breach of faith for the Commons to begin the trial while the King was negotiating a settlement with them.

The defence was legally correct in most of its particulars (though the last was a bit hypocritical when the King had been plotting war while negotiating peace). The Commons acting alone has never had power to act as a court. Even if it had, it was, following the coup d’état that was Pride’s Purge, no longer a representative assembly. The law of treason had never contemplated the prosecution of a king. The worst criticism of the court that tried its king, however, was that it was not fair, either in its appointment, its composition or its procedures.

The court’s verdict was implicit in the instrument by which it was set up (‘Whereas it is notorious that …’). None of the judges was independent; in fact, all were enemies of the accused and for the most part determined on his death; any backsliding was met by the personal intervention of the most powerful man in the land. And the prosecutor John Cook’s claim at his subsequent trial that his part was simply that of any lawyer dispassionately acting for a client was given the lie by a former pupil who had heard him declare: ‘He must die and monarchy must die with him.’18

Charles was given no prior notice of the charges against him, charges that were of the utmost gravity. And the only evidence called affected the outcome not one whit. The trial was a procedural disaster. Throughout the proceedings the court permitted, indeed, probably arranged for, the prisoner to be publicly intimidated and humiliated by the soldiers. Today, though not then, his refusal to plead should have been treated as a plea of not guilty.

‘CRUEL NECESSITY’

But none of this mattered to Parliament. The trial and execution of the King were political acts concealed only by a veneer of legality. As Charles rightly wrote in his defence, ‘power reigns without rule or law’.19 Rivers of blood had been spilt in the Civil War and the victors were determined to punish the person they saw as principally responsible for the tragedy.

For all its defects, the Civil War changed England for the better, perhaps the world. While Charles may have had the law on his side, the arguments deployed by Bradshaw probably represented the deeper feelings of the ordinary people. The king was not above the law; Parliament should not be merely an advisory body; sovereignty should lie, not with the king in person, but with ‘the King in Parliament’. Without the victory of Parliament the Bill of Rights of 1689 might not have happened. Without the Instrument of Government of 1653 America might not have hit on the idea of a written constitution.

There is no record of the King ever having met his nemesis, Cromwell, in life, but a story told by Alexander Pope to Joseph Spence in the eighteenth century recounts that after the execution a muffled figure, suspected to be Cromwell, visited the King’s corpse by night. Before turning away it was heard to mutter, ‘Cruel necessity’.20

CHAPTER TWO

The Diarist

The Trial of Sir Roger Casement, 1916

The U-boat arrived off the Bay of Tralee at dawn; it was Good Friday 1916 and the war with Germany was at its height. Three men dressed in civilian clothes attempted to row ashore, but their collapsible boat overturned in the surf and the expected reception committee was nowhere to be seen. The leader was a tall (6 feet 4 inches), thin, bearded man with intense deep-set eyes. Soaked to the skin, having gone without sleep for twelve days and still recovering from a nervous breakdown, he decided to rest in an abandoned Iron Age fort, while his companions buried their kit in the sands and made for Tralee.

A local farmer called the police when he discovered his eight-year-old daughter playing with revolvers she had found on the beach. The leader of the three was soon arrested and taken to the police barracks, where he was searched. On him were found field glasses, maps, ammunition and a German bus ticket. He had also been seen trying to destroy a document that contained what appeared to be codes. He gave the police a false name but later, when examined alone by a doctor who was a nationalist sympathiser, identified himself as Sir Roger Casement and asked for help in calling off the planned uprising against the British. The doctor duly contacted the Irish Volunteers, but they were suspicious of his story and did nothing.