Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

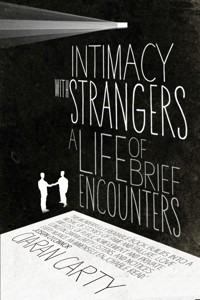

Intimacy with Strangers offers a dazzlingly original, thought-provoking approach to celebrity interviewing. Ciaran Carty draws upon a career involving many of the world's leading writers, artists, actors and directors as they explore intimate concerns, ranging from love and rejection to the smallest physical sensations of pleasure and pain, and to the great issues of politics and war, God and atheism – the big and small of the human condition. Interweaving recent cultural and social history, Carty exposes unexpected affinities shared by his eclectic cast of subjects. Through chains of happenstance and six-degrees-of-separation, Intimacy with Strangers mirrors the cinematic cuts, fades and dissolves of its author's sensibility as film critic and writer. By creating this magical memoir, Ciaran Carty offers an idiosyncratic portrait of a kaleidoscopic Ireland in a global setting.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 555

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Lilliput Press

Dublin

For Francis, Estefania, Antonio and Jack, and grand-daughters Ana, Emma and Rachel Cassidy

Acknowledgments

The interviews that shape the narrative ofIntimacy with Strangersare based on material originally published in various forms in theSunday Independentand later theSunday Tribune. The quotations haven’t changed but the context has in that it brings together in the present tense chance encounters sometimes separated by decades in real time.

I am indebted to all those who gave up their time to talk with me. Sadly some are no longer with us – Antonio Buero Vallejo, Anthony Burgess, Carmen Diez de Rivera, Kieran Hickey, C.R.L. James, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Hugh Leonard, John McGahern, Julius Nyerere, Harold Pinter and Natasha Richardson – but they live in their words and in the immediacy of each shared moment.

Many people have helped over the years in arranging introductions and setting up interviews, in particular Christine Aimé, Harry Band, Kate Bowe, Danielle Byrne, Michael Colgan, Geraldine Cooke, Ginger Corbett, Margaret Daly, Gerry Duffy, Gerry Dukes, Louise Fargette, Siobhan Farrell, Mick Hannigan, Fausta Hardy, Maud Haverty, Grainne Humphries, Janice Kearney, Cormac Kinsella, Anna Laverty, Trish Long, Gerry Lundberg, Brendan McCaul, Niamh McCaul, Charles McDonald, Sharon McGarry, Eilish MacPhillips, Joanna Mackle, Caroline Michel, John Miller, Liz Miller, Christine Monk, Barbara Murphy, Patrick Murphy, Rose Parkinson, Garth Pearce, Marie Rooney, Jonathan Rutter, Antonio Sierra, Graham Smith, Manlin Sterner, Lucie Taurines, Debbie Turner and Sarah Wilby.

I am also grateful to photographers Paolo Ardizzoni, Antonio Carty, Charles Collins, Mark Condren, Ann Egan, Francesco Guidicini, Geoff Langan, Trevor McBride, Aengus McMahon, Joanne O’Brien, Guido Ohlenbostel, Dick Scott Steward and Chris Sanders, and to Anna Bogutskaya, Pascal Edelmann, Olivia Guest, Madeleine McGahern, Louise Ryan and Lucki Stipetic for their generosity in providing illustrations.

I have been lucky throughout a career in journalism to work for editors who left me free to interview whoever interested me, wherever and whenever I wanted, and who published whatever I wrote without interference – Vincent Browne, Matt Cooper, Aengus Fanning, Michael Hand, Noirin Hegarty, Hector Legge, Peter Murtagh, Conor O’Brien and Frank Staniforth. Other colleagues who gave invaluable advice and support were Ros Dee, Diarmuid Doyle, Olivia Doyle, Nick Kelly and Brian Trench.

Intimacy with Strangerswas written on impulse and accepted by the first publisher who read it, a publisher who believes passionately in the importance of each book as an object in its own right. I am grateful to Antony Farrell of The Lilliput Press and his colleagues, Kathy Gilfillan, Sarah Davis-Gough and Djinn von Noorden, and especially my editor Fiona Dunne and designer Marsha Swan, for the enthusiasm and care with which they’ve guidedIntimacy with Strangersinto print.

Image Credits

Photographs of John McGahern by Madeleine McGahern; Kieran Hickey by Charles Collins; Darren Aronofsky by Ciaran Carty; John Updike by Geoff Langan; Doris Lessing by Chris Saunders; Mia Farrow by Ann Egan; Hugh Leonard by Eamon Gallagher; Julie Christie by Trevor McBride; Liam Neeson by Press Eye Belfast; Pedro Almodovar by Paola Ardizzoni and Emilio Pereda © El DeseoDASLU; Harold Pinter by Joanne O’Brien; Jonathan Miller by Gerry Sandford/De Facto; Amos Oz by Aengus McMahon; Ken Loach byEFA/Action Press/Guido Ohlenbostel; Wim Wenders and Danny Boyle byEFA/www.jens-braune.de and William Boyd by Dick Scott Stewart.

Images of André Brink, Kieran Hickey, John Updike, Mia Farrow, Julie Christie, Harold Pinter, Jonathan Miller, Amos Oz, William Boyd, Brian Friel, Hugh Leonard, C.R.L. James and William Trevor are courtesy of Independent Newspapers/The Sunday Tribune. The photo of Michael Caine inThe Actors, which was produced by Company of Wolves, is © Bord Scannán na hÉireann/the Irish Film Board.

Drawing of Mickey Rourke by Antonio Carty.

Ciaran Carty and The Lilliput Press express their appreciation to all copyright holders.

Introduction

While set in 2009,Intimacy with Strangersin a sense begins in March 1914 at a kitchen table in a house in Wexford town. My father Francis Carty is editing an issue ofThe Examiner, a journal he brings out at irregular intervals. It is handwritten in a school copybook and provides a commentary on the daily life of his family. He is fourteen, the eldest of five children. His mother, daughter of a sailing-ship captain, is a former teacher – the law required that she give up her job on marriage – and his father has a business on Main Street.

‘The railway bridge over the Crescent on Wexford Quay is composed of wooden planks,’ he reports in his editorial:

The storm on Saturday night washed away many of these planks, leaving holes for the unwary to fall into. On Sunday night a commercial traveller was walking over the bridge. He came to one of these holes and trod on the plank that wasn’t there. He went under, of course, but was fished out some time afterwards.

A younger brother, James, aged eleven, later to become a historian – hisClass Book of Irish Historywas for years a standard text on the Irish school curriculum – reflects on a lecture about earthquakes delivered in the town hall by Father William O’Leary from Mungret Observatory College. ‘The science of seismology now only in its infancy is growing and the time is not far distant when not only will it record earthquakes but foretell those that will come,’ he predicts.

There is a photograph ‘taken by the editor’ of his grandparents sitting by the fireplace in the kitchen. He notes that they will be celebrating their golden wedding anniversary on 25 April 1918.

This seems to have been the last issue ofThe Examiner. The Great War broke out later that year. In 1916, Republicans led by Patrick Pearse and James Connolly seized the General Post Office in Dublin, issued a Proclamation of Independence and held out for a week against British forces before surrendering. My father took a train to Dublin hoping to join the revolution, but got off at the wrong station.

His father, a hairdresser who opened a salon in 1896 offering ‘the latest London styles’, was by then a town alderman. He proposed an amendment to a motion condemning the Easter Rising in which he urged that ‘leniency be shown to the rank and file’. It had no effect, of course. The British army rounded up the leaders, summarily executed most of them by firing squad, and deported many others to jails in England.

Grandfather Francis Carty at the family business of North Main Street, Wexford, 1896.

The amendment was regarded as a stab in the back of John Redmond, the local MP and leader of the Irish Party in Westminster, who had obtained a promise from the British government at the outbreak of the war that if he encouraged large numbers of young Irish men to join up – which they did – Home Rule would be granted when hostilities ceased. Redmond’s supporters boycotted the Carty business on Main Street but their custom was soon replaced by supporters of Sinn Féin, the Ourselves Alone party that declared ade factoRepublic in 1919 following countrywide election successes.

My father as a member of its local publicity committee was appointed registrar of a Republican Arbitration Court, used by the town’s mayor, Richard Corish, as a tactic to bypass the British-run local petty sessions court. Law-breakers were arrested by Irish Volunteers and brought to trial, fines were imposed and my father supplied reports to newspapers.

On one occasion the entire court including my father was seized and brought under arrest to the military barracks, but released the following day without charge.

By the summer of 1920 my father had risen to battalion adjutant of the Volunteers in south Wexford, organizing raids on Royal Irish Constabulary barracks, smuggling arms from abroad, raiding the mail trains and blocking roads. He used his home on Main Street as a headquarters. Because he was so openly identified with the civilian side of the campaign for independence, his military activity was not suspected by the Black and Tans, a mercenary force brought in by the British to use terror tactics to subdue the population.

He was an improbable revolutionary, a small quiet man of five-foot-five and not yet twenty-one, an ordinary citizen caught up in a popular resistance movement against occupation forces.

He fictionalized his experiences in a novel,The Irish Volunteer, published in 1934 by Dent in London and favourably reviewed by Graham Greene. A second novel,Legion of the Rearguard, dealt with the civil war that split the IRA in 1922 when the British, under pressure of international opinion, called a truce and then negotiated a treaty with Michael Collins – bitterly opposed by Eamonn de Valera – which established an Irish Free State, but partitioned the country: a familiar imperial strategy of divide and rule.

My father was lucky not to be shot by the Black and Tans or by Free State troops who captured him during the Civil War and imprisoned him in Portlaoise, where he attempted to burn down the gaol. He then took part in a 23-day hunger strike in protest at being forced in punishment to sleep out in the yard in the middle of a winter snowstorm. He survived the ordeal and helped campaign in the election that swept de Valera to power in 1932. Instead of entering politics he became a journalist onThe Irish Press, a newspaper set up by de Valera because all the existing newspapers opposed him.

After the war my father moved into publishing as manager of The Parkside Press and editor ofThe Irish DigestandThe English Digest. Going through papers in his study one day I came across a copy of his boyhood magazine,The Examiner,and had the idea of resurrecting it asThe Carty Digest. He allowed me to use the upright Remington typewriter on which he wrote his novels and radio plays. I was fourteen, the same age he had been in 1914.

My young brother Francis Xavier contributed a brief autobiography: ‘My life, to the present day, has been a simple one. Part of my school time has been dull, but the rest has been cheerful and happy. I hope my future will be as happy as my past.’

Alice Carty honeymooning in Belgium, 1934.

Our mother Alice, a pianist and editor of two English reading books for schools, submitted a short skit about a Fianna Fáil election poster she spotted on the wall of a cemetery urging voters to ‘Put Them In’. Her father had worked with Dublin Corporation and was involved in planning Fairview Park in the 1890s. The family sided with Michael Collins in the Civil War – her elder sister married one of his henchmen – and she was an admirer of Dr Noel Browne who, as Minister for Health in the Fine Gael-led coalition government, sought to introduce a ‘socialist’ Mother and Child scheme against opposition from the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid. She met my father when she accidentally hit him with her racket at a tennis club. She was obliged to give up her job in the civil service to become his wife: nothing had changed for women in the Free State, they were still not allowed work after marriage.

‘The Constitution says a woman’s place is in the kitchen,’ she told me. ‘Get a voice. Speak out against injustice. Don’t let that continue.’

•••

Intimacy with Strangers: A Life of Brief Encountersjourneys over time through interviews with writers, actors and artists, living and dead. It maps out the shifting landscape of a world of seemingly unconnected lives and experiences that trigger surprising associations, all against the backdrop of a century of war and violent change.

The cast, playing themselves in this wider narrative of which they are unaware, includes Woody Allen, Kim Basinger, Chuck Berry, Beyoncé, William Boyd, Danny Boyle, Michael Caine, Julie Christie, Leonardo DiCaprio, Brian Friel, Werner Herzog, Angelina Jolie, Hans Küng, Hugh Leonard, Doris Lessing, John McGahern, Liam Neeson, Jack Nicholson, Harold Pinter, Mickey Rourke and John Updike. The book is framed by echoes of past encounters that resurface over the course of a single year in my job as an interviewer, working to newspaper deadlines. The chronology strays beyond the initial journalistic challenge as thoughts and moments from earlier interviews as well as personal memories insist on intruding to form patterns and reflections on the nature of art and time and chance, like a ribbon of dreams, which is how Orson Welles described film. A parallel career as a film critic, it seems, has fed into the experience of interviewing, one conditioning the other.

Four years before his death in 1986, Jorge Luis Borges attended a reception in his honour in Dublin Castle. He sat in a straight-backed chair by the wall, his hand on a polished ebony walking stick, a blind man listening. Although he was fluent in English since childhood, it seemed appropriate to talk to him in Spanish. It was the day Port Stanley was captured in the Falklands/Malvinas war. ‘A lost cause,’ he said, sadly. The bloodshed appalled him. ‘So futile. And the older you get the more futile it seems.’

To know me, all he had to go on was what he heard me say. If it had been an interview all I would have had to go on afterwards would have been what was on the tape. You relive an interview like a blind man, listening without seeing. You are a detective putting together evidence of a life briefly encountered. You bear witness.

All we can ever do, as renowned Australian clinical psychologist Dorothy Rowe argues, is create theories or guesses about what another person is thinking or feeling: ‘Our guesses come from our experience and, since no two people ever have exactly the same experience, no two people ever see anything in exactly the same way. Thus we each live in our own individual world of meaning. Empathy is always a leap of the imagination.’

Even those who are closest to us cannot be more than imagined selves. Maybe this is what makes love so compelling, the mystery of longing to know someone intimately but never fully knowing.

When an interview goes well there can be a meeting of minds, an empathy with someone other than our self, which, through the process of writing, communicates some deeper sense of who that other is. But it is ultimately no more than a sketch for a portrait that readers must complete for themselves. There is never a definitive portrait because something of the subject will always remain unknown, an imagined other.

We are our memories and the memories of others. In the beginning was the past and the past is present. Take the experience of Thomas Kinsella when he was putting togetherThe Oxford Book of Irish Verse. He unearthed lines of poetry probably written by a monk in the eighth century as he finished his day’s more tedious job of transcribing sacred scripts. He was interrupted by a bird singing outside his cell and was moved to jot down some lines in a margin of his manuscript:

My hand is tired,

I’ve had an awful day.

Isn’t that a terrific blackbird.

The freshness of the moment lives on hundreds of years later through the immediacy of a verse. ‘You have access to a mind that really is alive and responding to sensual artistic detail in a way you never would from any other source,’ says Kinsella.

This was in 1981 at the time of the publication ofAn Duanaire, which he had translated with Seán Ó Tuama, a groundbreaking anthology in Irish and English of ‘poems of the dispossessed’ from the period between the collapse of the old Gaelic order and the emergence of English as the dominant vernacular.

Thomas Kinsella, Percy Lane, Dublin, 1981.

Kinsella is a poet who, like the old Gaelic scribes, had a day job. As private secretary to T.K. Whitaker in the Department of Finance he worked on the Programme for Economic Expansion that brought industrial and social transformation to Ireland in the 1960s.An Duanaireis something of a departure from the main body of his poetry, which is written in free form with few concessions to popular appeal. Each of his poems, whether inFifteen DeadorOne and Other Poems, has a shape of its own, like an uncharted territory without maps to guide the reader.

‘You have to make your own maps, especially in these times,’ he says. ‘You have to find your paper and your pencil and pare it. We’re out in the woods as those early scribes were. The whole thing has to be done all over again.’

While he was in the mews of his house in Percy Lane translating the lines about the blackbird, it came back to him how in Philadelphia in the 1960s, when he was translating the Irish prose epicAn Táin, he had been interrupted by a mockingbird:

There it was, exactly the same. So I jotted down that memory. And then all these years later before I knew what was happening, there was a thrush hopping out and eating an ivy berry off the opposite wall in the garden outside this window. So I had three dimensions of the same thing. The birds are doing what they always did. So are we. To be able to make that sensual contact is a marvellous thing.

•••

It’s early March, ten years later. Paul Auster is sitting on a leather couch beside an open fire in the foyer of the old Shelbourne Hotel in Dublin. Through the glass revolving door people hurry past along windswept St Stephen’s Green, huddled under umbrellas. He lights a cigarette, a ritual that will later provide the motif for his filmSmoke.

He is a tall man with strong sculpted features, vaguely Byronic: long nose, full lips, deep dark eyes and wavy black hair; accidents of birth, no doubt. ‘Everything is born out of chance,’ he says. ‘Just think of the chance that brought your parents or mine together. We are children of chance. Things happen to us at random. So why should fiction not be able to include these kinds of incidents, which seem to me the very stuff of life.’

He recalls being a little boy of four in Newark. ‘I had a trick record my mother bought for me. It skipped a groove, and a different story would be told. It was chance whatever story you heard.’

Fiction traditionally imposes order on life, trying to make sense of it. Allowing things to happen out of the blue is frowned on. Plot demands that there should be a reason for everything. By defying this taboo, Auster opened up contemporary fiction to a vast but little-explored area of experience. The more outrageous the coincidence inNew York Trilogy,Moon PalaceorIn the Country of Last Things, the more likely it is to happen. ‘You can take any subject or character and start spinning associations,’ he says.

InThe Music of Chancea fireman who has unexpectedly inherited $200,000 from a father he never knew drives aimlessly across America in a red two-door Saab 900, eventually picking up a card shark whom he bankrolls in a bizarre poker game with a couple of elderly eccentrics who won $27 million in the Pennsylvanian State Lottery. ‘Never underestimate the flukiness of our existence,’ Auster says.

A lot of people don’t see coincidences. They walk along a straight path. They have an idea of where they want to be the next day, the next year. But if you’re never really going anywhere, which is the feeling I’ve had all my life, you tend to wander a bit more, you keep more open to the unexpected.

He started wandering as soon as he left high school, heading for Dublin with money he’d saved up.

I stayed in a bed and breakfast in Donnybrook and walked every day, all day, just combing the streets. I was so shy I never spoke to anyone. I didn’t dare go into a pub. I didn’t do anything. I just walked. And for years afterwards, whenever I closed my eyes and was about to go asleep, I’d be walking through Dublin.

But he did go into a shop to buy a suit. ‘And I literally wore it every day for my entire freshman year at Columbia University, until it fell apart.’

It’s the coat the eccentric Marco Polo Fogg wears inMoon Palaceon his search for his lost father, just as Uncle Victor, who goes away leaving him crates of books, is based on one of Auster’s uncles:

He was a translator of Dante and went off to Italy for twelve years. My parents had no education. They didn’t have any books in the house. So they put his books in the attic. But when I was ten my mother went up and said all the books were going to rot if we kept them in boxes. Let’s take them downstairs and put them on shelves. And that’s how I started reading. It was completely arbitrary reading, whichever books happened to come out of the boxes.

After graduation, Auster worked as a merchant seaman and lived in France for two years, writing poetry. Samuel Beckett befriended him. ‘He was very gracious. But it was terrifying. Tell me about yourself, he said. This was the last thing I wanted to talk about.’

•••

Now it’s autumn, another hotel, same year. Blakes in South Kensington is a haunt for celebrities who don’t want to be bothered. The fashionable designer Anouska Hempel combined two Victorian houses into one on a quiet residential street off Brompton Road. The décor has oriental associations.

Robertson Davies is staying here. Tall and imposing in a quaintly old-fashioned three-piece tweed suit with silk handkerchief in top pocket, his bushy white hair and beard give him the aura of a Shavian Methuselah. The youngest of his family, but now seventy-seven, the Canadian novelist and one-time journalist has memories that reach back beyond the last century as if it were yesterday.

As a child he heard talk about how his great-grandmother fled up the Hudson River in a canoe with her family after the defeat of the English in the American War of Independence. ‘They had to get out because they were loyal to the crown. They were impoverished and victimized, arriving in Canada with enormous numbers of other refugees. This is what the United States does not like to remember.’

His mother, who gave birth to him when she was forty-four, was born in 1869 and her mother in 1824. ‘I remember them both very well, so there is a stretch of memory that goes way back. You get a sense of the absolute reality and actuality of history, hearing it from someone who really has been there or talked to somebody who was.’

Davies injects this sense of a living past into the characters that recur in his novels, like real people accumulating memories. His novels tend to group into trilogies –The Deptford Trilogy,The Saterton TrilogyandThe Cornish Trilogy(which includes his 1989 Booker Prize-nominatedWhat’s Bred in the Bone).

His latest,Murther and WalkingSpirits, might seem an exception: at his age it would be perhaps presumptuous to contemplate another trilogy. ‘It’s complete in itself,’ he says. But in fact it’s really four novels in one. Murdered in the first paragraph, the hero becomes a ghost, time-tripping back and forth through the lives of his various ancestors:

I wanted to suggest that he might, like any of us, have thought he was alone and self-sufficient, purely an individual. But nobody is that. We are all a combination of what we’ve been made by people in the past. And we are contributing to what people will be in the future. We’re really beads on a string rather than single beautiful gems.

Which gives an ingenious new twist to the autobiographical fiction genre: Davies through his protagonist Gil, a journalist, as he was for much of his life, in effect becomes a witness to his own distant origins. Stories his great-grandparents told their children, who then passed them on to his parents, are woven into the narrative. Chance events and coincidences lead inexorably to his present self through the misadventures of his mother’s Loyalist ancestors, driven north to Canada, and through the poverty that forced his Welsh father to emigrate during the great depression of 1894, a printer who used his Celtic feel for words to become publisher ofThe Peterborough Examiner, the paper that Davies himself would edit for nearly twenty years.

Davies was brought up to be curious not only about the past but about everything around him:

We moved a good deal around Canada as my father acquired larger and larger papers. I saw quite a lot of different people and different places when I was very young. I knew all the news that was fit to print and, more interesting still, all the news that was not fit to print. As my mother was not well, my father would entertain her by bringing home the ripest gossip and amusing her with it at meals.

But it was a staunch Presbyterian upbringing, too, inculcating an obligation to make sense of life that has fed into his fiction. He had to learn by heart the shorter Catechism:

Which was not short at all. By the time you’ve chewed through that, you’ve got a lot of answers to rather difficult questions. They may not be completely satisfactory, but at least they’re something. A lot of people today are religiously illiterate. They think people who have religious beliefs believe stupid and impossible things. They’ve never looked into it to find out what they really do believe or why. So they’re rather bereft. They’re lacking any insight into one of the great concerns of mankind.

Going off to become an actor with the Old Vic in the 1930s made Davies something of a renegade. There he became a lifelong friend of Tyrone Guthrie, and was horrified to discover when he visited Annaghmakerrig, an artists’ haven in Monaghan bequeathed to the Irish nation, that Guthrie’s grave was overgrown with weeds. ‘It looked like the neglected grave of a dog.’

He hardly had time to meet and marry Brenda, a stage manager and his wife of fifty years – ‘It’s been a long conversation’ – before the war closed down all the theatres, forcing him to return to journalism in Canada, ‘the family trade’. His numerous columns, collected asThe Diary of Samuel Marchbanks, launched him as a writer:

People say that journalism spoils a writer’s style. It’s just baloney. I enjoyed the work and meeting people and knowing what was going on. A criticism I would make of some novelists is that they don’t seem to know anybody but other literary people. They don’t know a shopkeeper or a farmer or children or any ordinary people. It gives them a very squint-eyed view of life.

Davies is living out his last years in the countryside beyond Toronto, ‘a very clean and orderly place which Peter Ustinov likened to New York run by the Swiss’. His neighbour, the director Norman Jewison, filming there because it was cheaper than in the US, had garbage dumped in the streets to make them pass for New York. ‘When the property people returned from lunch, it had all been cleaned.’

Although he has a swarm of grandchildren, he doesn’t get a chance to talk to them the way his grandparents did with him. ‘It’s very hard to pass anything on to them because I don’t see them very often. And when I do they just smile and that’s all there is to it.’

He feels compelled to continue writing fiction to keep memories alive for them. ‘It’s gone if nobody passes it on.’

•••

Charlton Heston thought nothing of being John the Baptist, Moses, Ben Hur and Michelangelo, or even God. He played all roles with a gravitas that made him a Hollywood icon. But being himself was something else. ‘Many actors are in fact shy people,’ he says. ‘That’s one of the reasons why they pretend to be other people.’

We’re in a lift in the Shelbourne Hotel on our way up to his room. It’s late November 1995, long before Alzheimer’s disease would purge all his memories and shut him off from the world.

He takes me to a couch by the window looking out onto St Stephen’s Green. Perhaps his shyness has to do with growing up alone in the vast forests of the Michigan peninsula, where his father had a timber company. ‘I had no playmates, but that’s because there weren’t any children nearby. I was happy roaming the woods, hunting and fishing. All kids play pretend games and I did it perhaps more than most, acting out the books I read.’

At ten his life changed drastically and forever. His parents divorced and overnight he was on a Pullman car heading south with his mother, sister and baby brother:

It was the most traumatic experience of my life. But then again, if my parents had not divorced I’d never have gotten to Northwestern University and studied drama. I’d never have met my wife Lydia, who has made my life, and we wouldn’t be talking here with the sun shining in the window.

At school in Wilomette, Ohio, he was a gauche kid from the backwoods, nervous even about crossing a paved street with moving cars. His parents’ divorce was ‘a dark and terrible secret I told no one’. It was only when he began acting in school plays that he felt at ease. Already by his late teens he had the gangling six-three build that, with his piercing blue eyes from his Scottish ancestry, distinctive broken nose acquired at high-school football and a deep voice, would make him a screen natural.

His later life has been lived with Lydia on a ridge in Beverly Hills surrounded by several hundred acres of Water Department woodland:

The only thing I leave here for is to act. Actors have a public identity that they have to learn to be. I have been a public man for much of my life. It’s the public man that’s speaking to you now. I don’t mean to imply that I’m a Jekyll and Hyde. But the public man is still a different kind of person, slightly more outgoing, more communicative.

One thinks of actors as outgoing people, loving an audience. That’s singers and comedians. They talk directly to the audience. Listen, they will say, looking right at you, and the next song I’m going to sing I heard in a little coffee bar, and I think you’ll like it. But an actor on the stage is not relating to the audience. He’s doing the play. The audience is watching. He’s within the play. And of course in film, the audience is a year down the road.

Paradoxically, being a star is Heston’s intuitive way of keeping a distance, as it is for Joan Allen, who is more readily thought of as the characters she plays than as Joan Allen. There is a sense in which she seems to live through who she becomes.

She’s more comfortable being a suburban mother escaping conformity inPleasantville, the long-suffering wife of a disgraced president in Oliver Stone’sNixon, or the wife in Nicholas Hytner’s film version of Arthur Miller’sThe Crucible, who realizes that by lying to protect her adulterous husband during the Salem witch-hunts she has in fact damned him, than she is in being Joan Allen.

‘I was raised in a conservative Midwest family,’ she says.

One thing you learn is that you don’t talk about religion and you don’t talk about politics. It was a kind of rule of thumb in my house. As a child I probably felt not very comfortable in how I was and like some people do, I tried to find a way in which I could express or pretend to be other people or to reveal aspects of myself in the guise of a character. I find a lot of actors are like that. They sometimes are very reserved in themselves.

She went through agony during the run-up to the Oscars in 2001 when Ang Lee invited her to present him with his American Directors Guild nomination for best director forCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. ‘Julia Roberts was going to introduce Steven Soderbergh forTraffic. Russell Crowe would be there to introduce Ridley Scott forGladiator, so Ang asked me, because we knew each other so well fromThe Ice Storm.’ She gives a shiver. ‘It came off all right, but to be myself in front of people and make a speech and know that I was saying my own words was an incredible burden for me. I find it most difficult when I have to be myself.’

•••

Maybe interviewers are like actors in this respect. I was chronically shy as a child, hiding in daydreams. Books were an escape into other worlds reimagined in minutely detailed, painted comic strips or by modelling characters and landscapes in Plasticine, turning their stories into plays performed by little cut-out puppets in a handmade cardboard theatre. Lying in bed, that child, who in memory seems like another person, fell in love with the contralto voice of his sister Jane’s friend, Bernadette Greevy, as they practised duets downstairs to his mother’s piano accompaniment. In the middle of the night he roamed the world, turning the dial on the radio and shifting wavebands, listening to a babble of languages, the lights out and the curtains open to the stars.

He typed out with two fingers on his father’s upright typewriter stories with surprise endings, a formula assimilated from the collected stories of O. Henry, Guy de Maupassant and Damon Runyon, and found the courage to submit one toThe Evening Herald. Seeing it in print and receiving a cheque for £3 – his pocket money at the time was six pence a week – emboldened him to embark on a book about howhomo sapiensfirst evolved in Africa in the Olduvai Gorge, disproving the arrogant colonial claim that Africans were not intelligent enough to govern themselves.

Holy Ghost priests who were in Africa as missionaries spoke glowingly in class about their experiences. His father made journeys there accompanied by a publishing colleague from Macmillan in London, with the idea of translating the existing schoolbooks from English into Ibo, Swahili and other indigenous languages. Eager to learn more about this exotic continent that seemed so near, through his father’s letters, he tried to make contact with revolutionary nationalists who were struggling to win independence for their countries.

Months later a letter came back from a former mission school teacher, Julius Nyerere, typed out on five pages of flimsy airmail paper, introducing himself and spelling out his dream for a free Tanganyika. ‘I was born thirty-seven years ago in Butiama in the Musoma district of the Lake Province. I am married and have five children. I now live in Dar es Salaam. I have no hobbies.’

Nyerere was leader of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), a party claiming to have 700,000 members, which had just won twenty-eight of the thirty seats for the legislative council. ‘The elections are artificial because the constitution is an artificial one,’ he wrote. ‘The voters were required under law to vote for three candidates, one from each racial group. This device of racial representation was invented to emphasize and entrench the racial divisions in this country. We were opposed to it. When we failed to get it abolished we decided to use it to explode the bogey of race.’

He set out how he hoped to unite Tanganyika and persuade the British to leave through debate and reason rather than violence:

I have a notorious reputation of being a moderate. I can distinguish between the ideal and the possible. I know that we cannot push the British from Tanganyika; but I know that as long as they allow us freedom of organisation they will soon find it impossible to govern us. I give them a maximum of six years. The people of Tanganyika don’t want to wait one more minute. The question, therefore, is not whether the people of Tanganyika will wait that long, but whether the British will be stupid enough to wait that long.

This was April 1959. Nyerere was true to his word. Harold Macmillan made his famous ‘Wind of Change’ speech. Within three years Tanganyika peacefully achieved independence as the new sovereign state of Tanzania, with Nyerere as its first president. Writing this up in an article while still a student, a first attempt at an interview, failed to impressThe Irish Times: they didn’t even bother to send a rejection slip. Nyerere was little known. Africa was not yet on their radar.

Having just graduated in economics from UCD this would-be journalist left home for experience on a weekly paper in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, then emigrated to England as a subeditor onThe Northern Despatch. On the strength of the rejected Nyerere piece he was interviewed by Anthony Sampson forThe Drum, a paper established in South Africa with black journalists to challenge the apartheid regime. UPI at the same time offered a job in their London bureau.

Instead he returned to Dublin to a staff job on theSunday Independent, a rival paper toThe Sunday Press, which his father edited, having been brought in to runThe Irish Pressin 1957 because de Valera felt its coverage of the IRA had become too sympathetic.

The chance to go to Africa was tempting, but a few months earlier he met a dark-eyed, vivacious 22-year-old Spaniard, Julia Alonso Beazcochea, in Darlington, England, to learn English. She was going back to Madrid. He didn’t want to lose her. She joined him instead in Dublin and they married that summer.

Julia Alonso Beazcochea boating in the Isle of Skye, 1960.

•••

Joan Allen says that an attraction to otherness was why she became an actress. Acting took her out of herself to become herself. Writing provides a similar release, allowing a way into other people’s worlds, setting up encounters where it is possible to talk freely with a stranger and then make sense of it on the page. It can become, as it has for me, a life of getting personal with people you have never met before and may never meet again.

It’s like stopping at a traffic light. You glance at the car beside you and glimpse a face behind the wheel, lost in thought. The lights change. The car pulls away. You wonder who this person is whose life has briefly touched yours but you will never see again. Yet out of billions of lives in the world and over time, each a link in its own chain of intimate but interconnecting memories and longings, the likelihood of meeting at random a person who knows you or someone from your past you didn’t know you had in common is much greater than it might seem.

Shaking the hand of Robertson Davies, whose mother was a granddaughter of a woman who escaped up the Hudson in a canoe in the late eighteenth century, meant that I, too, was touched by that history, reaching back through two centuries as if it were only yesterday. Paul Auster’s memories of his childhood and of an uncle who hoarded books are as real to me through talking with him as any memory of my own. The song of a blackbird overheard by a monk in the Middle Ages is my song, also.

Attempts have been made to rationalize this sense of being just a few heartbeats apart from anyone else. The May 1967 issue ofPsychology Todayfeatured an experiment by the sociologist Stanley Milgram, which purported to show that everyone is connected by an average of six degrees of separation. Although the empirical basis for his conclusion was dubious, the idea caught on. It inspiredSix Degrees of Separation, a tragicomedy by playwright John Guare in which, as Frank Rich enthused inThe New York Times, ‘broken connections, mistaken identities, and tragic social, familial and cultural schisms … create a hilarious and finally searing panorama of urban America in precisely our time’.

The plot pivots on the readiness of people to accept without question the idea that they might be connected with someone famous. A personable young black man turns up at a Manhattan apartment, distraught and bleeding from a slight stomach wound. He explains to the smart art-dealing couple who live there that somebody mugged him in Central Park. He made for their address, the only one he knew in New York, because he’s a Harvard friend of their son and daughter. As he’s cultured and articulate – and, he lets slip, the son of film star Sidney Poitier – they eagerly buy into his story, patch him up, and let him stay the night. When he turns out not to be what they imagined they feel betrayed, even defiled. But is he conning them or are they conning themselves?

Guare’s play was a success on Broadway and the West End. His subsequent screenplay, directed by Fred Schepisi, didn’t so much open out the story as provide the New York detail that was previously left to the audience’s imagination. It launched the Hollywood career of Will Smith – then better known as a Grammy-winning rap artist – who was engagingly persuasive as the young man who so smoothly became a catalyst in the couple’s safe lives, challenging their assumptions and those of all the ‘haves’ they represent. It enhanced popular belief in the ‘small world’ theory that, as Stephen Poole commented inThe Guardian, ‘everyone is a new door opening into other worlds … Everybody on this planet is separated only by six other people … but you have to find the right six people to make the connection.’

It became a parlour game calledSix Degrees of Kevin Baconin which any Hollywood actor can be linked to Kevin Bacon in six steps. ‘I thought it would have gone away a long time ago but it seems to have a tremendous amount of hang time,’ Bacon said several years later. ‘I was bugged by it at first and then I got used to it and came to see it as amusing.’

Amusing it may be, but hardly science. In the March/April 2002 issue ofPsychology Today, Judith Kleinfeld reappraised Milgram’s theory and found that its conclusion had ‘scanty evidence’ and could be just ‘the academic equivalent of an urban myth’, although the chances of making a ‘six degrees of separation’ connection were probably high ‘for educated people who travel in similar networks’.

Since then the advent of Internet blogs and Twitter, Facebook and MySpace friendships and myriad other forms of online social intercourse have created a cyber world where anyone can plausibly connect with anyone they choose anywhere in the world. We experience through live satellite television the euphoria of being, say, with Barack Obama’s family at the moment of his inauguration, or hearing the dying cough of a young Iranian woman gunned down during street protests in Teheran, or watching helpless as people are swept to their deaths in a tsunami.

Over a lifetime of interviewing it’s hard not to feel a sense of being a link that, unknown to the subjects, in some way brings them together in a single consciousness where they play off each other, their experiences and their ideas forming a shared narrative. Their words rerun on a memory tape evoking resonances in unexpected ways, prompted perhaps by a snatch of music on a car radio or a film repeated on television, or a painting in a gallery, or picking up a novel or some poems while browsing in a bookshop.

An interviewer over time becomes like the angel portrayed by Bruno Ganz in Wim Wenders’ elegiacWings of Desire, a ghost wandering through the lives of others, listening and observing unseen, in the way a barman is unseen, someone to talk to but not really remember. The format of an interview allows freedom to talk close up with strangers with a freeness you rarely achieve with a good friend or family member.

The concept forIntimacy with Strangersemerged early in 2009 while completingCitizen Artist, the second volume of a biography of the painter Robert Ballagh: the first volume,The Early Years, was published by Vincent Browne in 1986. Mirroring the way Ballagh bases his paintings on photographs of his subjects, the biography drew on years of interviews recorded with him and others who know him since our first meeting in 1977. It took the form of flashbacks while observing a particular work in progress, his portrait of Professor James Watson, the genetic scientist whose Nobel Prize-winning discovery with Sir Francis Crick of the double helix in 1953 led to the decoding of DNA and the secret of life. The observation of an artist’s day-to-day engagement with society becomes a personal chronicle of the times: all art and literature is in one way or another an ongoing dialogue with the world in which it is created.

Intimacy with Strangersis an attempt to apply this approach to interviews with writers and artists whose work provides a cultural mirror of the good, the bad and the beautiful of recent decades, an alternative narrative. Its concept owes something to a series of documentary histories written by my uncle James in which he used contemporary reports and testimonies to provide a version of Irish history, in all its contradictions, through the eyes of people who lived it.

The art critic Adrian Searle argues that all photography has an undeniable autobiographical element. ‘After all, the photographers had to be there, even if they were on assignment,’ he says. Interviewing is subjective in the same way. In talking to others you find you are also talking to yourself. Moving back and forth through time and place in a life of interviews occasions all sorts of associations that mightn’t have been apparent at the time but now form interweaving chains of unexpected connections, imbuing the past with a sense of the living present, an eclectic parallel history.

There is a strange intimacy about an interview that lingers on even if the interviewer and the interviewee never meet again. You can’t talk in depth with someone without being changed by it. You imagine yourself into his or her life in a way that makes them characters in the story of your own life: the interviewer becomes, in some oblique way, the interviewed. This book is an attempt to give some shape and make some sense of years of such intimacy with strangers.

Ciaran Carty on the Croisette during Cannes Film Festival, 2009.

WINTER

one | Danny Boyle, Kieran Hickey, John McGahern, Anthony Burgess and Chuck Berry

John McGahern at home in Mohill, Co. Leitrim, 1978.

‘That’s Bombay, movies and excrement. You smell it when you get there – there’s no smell quite like it. But then it’s gone and you smell jasmine, and it’s like heaven …’

Danny Boyle is talking on tape aboutSlumdog Millionaire, a rags-to-riches romance about a penniless shanty-town orphan who wins instant fame in India’s version ofWho Wants to Be a Millionaire.Never mind that up to now a foreign film, partly in Hindi with English subtitles and without box-office stars, would be unlikely to get a release in the US, let alone find favour with Hollywood. America, it seems, is losing its Bush-induced xenophobia. There’s a growing curiosity about otherness. As 2009 rings in,Slumdog Millionaireis already building up Oscar momentum.

‘One thing after another, those are the contrasts you get in Bombay, those are the extremes. It’s an incredible setting for a thriller with its out-of-control money and corruption and this deity, these gods of Bollywood with all their glamour and wealth …’

Transcribing a tape is the most tedious part of an interview, earphones plugged in, clicking on and off, winding back and trying to check what’s said, reliving the immediacy of each moment. Pauses and unfinished sentences can be more revealing than the actual words. As you listen, ideas form, a narrative begins to take shape. There are times when you hear yourself interrupt a fraction of a second before the person being interviewed begins to say something unexpected, but then holds back to allow you to continue, and you mutter at your taped self, ‘Shut up, shut up.’ Interviewing is about listening, not unlike a priest in a confessional or an analyst beside a couch.

And always there’s the problem of deciphering what you have scribbled down, perhaps in too much of a hurry. You check back with the recording, again and again:

We think of these slums as being full of abject poverty. But they’re not. There’s poverty, of course. But what they’re full of is business. Everybody is making deals. It feels like life is being lived to the maximum the whole time – they just go for it. There’s movement and energy everywhere, and an extraordinary sense of dance and Bollywood dreamland …

Each tape can take two hours or more to transcribe. It’s hard to stay focused. Right now in the garden below my window a bird is pecking at a rotting apple left on the grass from autumn. It only takes what it needs and then flies off. It will be back tomorrow for another bite. This is a seasonal ritual, an understanding that has developed. You don’t think of birds as individuals but each one has a life of possibly ten or twenty years. They form a relationship with the garden and what they can expect to find there.

I first heard of Danny Boyle from Dublin film-maker Kieran Hickey when he was a drama producer with BBC Northern Ireland over twenty years ago. With virtually no funding for films available in the Republic, Irish film-makers looked to Channel 4 and the BBC for backing. Hickey’sA Child’s Voice, a psychological thriller with T.P. McKenna as the demented victim of one of his own late-night radio ghost stories, was one of the few significant breakthroughs in Irish cinema in the late 1970s. The BBC screened it three times and it was acclaimed at Chicago and Melbourne film festivals. Yet it wasn’t screened in Ireland until five years after its London Film Festival premiere in 1978. ‘Nobody would put up any money,’ Hickey told me. ‘We had to finance it entirely ourselves. Making a film in Ireland is almost an afterthought to the effort of convincing people that you can make it.’

Hickey grew up in a terraced house off the South Circular Road in Dublin. He found James Joyce’sDublinersandA Portrait of the Artist as a Young Manan escape from the rigid nationalism and religious dogmatism drummed into him at school:

Kieran Hickey, Dublin, 1987.

It was immensely reassuring to know a writer who understood what urban life was about. I reached [out] to Joyce because he related to my own experience. What I had in front of me in his work was there in my everyday life. Something as simple as that was in its way more shattering than any other statement he could have made: the realization that there could be art in, as Joyce put it, naming the Wellington Monument, Sydney Parade, the Sandymount tram, Downes’ cake shop and Williams’ jam.

Hickey was exhilarated by how Joyce deconstructed time and space, using disconnected words to suggest incident and convey a psychological whole: he defied conventional ‘clock’ chronology, rendering transient impressions and relationships through the literary equivalent of cross-cutting and flashbacks. ‘Joyce learned to look at the world in a cinematic way before cinema had really been invented.’

Hickey was reared on Saturday matinées, eventually graduating to the more refined offerings of the British Film Institute in the early 1960s, poring overCahiers du Cinémawith another young film buff, David Thomson, who remained a friend for life and scripted some of his short fictional films. ‘He was a terrific, eloquent talker – gruff, tender, lyrical, sarcastic,’ writes Thomson in his invaluableThe New Biographical Dictionary of Film. ‘You could feel yourself starting to think better and faster in his company.’

Hickey first attracted critical attention in 1967 withFaithful Departed, a brilliant evocation of Joyce’s Dublin drawn from a forgotten collection of over 40,000 Lawrence photographs he discovered buried in the National Library. ‘They conveyed this frozen sense of time,’ he said, describing his thrill on first seeing them. ‘They recorded visually the images of Dublin Joyce had taken away in his mind and in his heart and later drawn on in his writing. They give us a glimpse of the Dublin that had become fixed in his memory.’

AlthoughFaithful Departedwas chosen to represent Ireland at the 1969 Paris Biennale, Hickey was only able to film it with the backing of the BBC. His later films,Exposure,Criminal Conversation,A Child’s Voiceand William Trevor’s story,Attracta, challenging taboos of sexuality and political hypocrisy, all relied on BBC support, too. Ireland wouldn’t have a proper film industry until Michael D. Higgins became Arts Minister in 1993, too late for Hickey. He underwent open-heart surgery that year. The bypass was a success but he died from an embolism soon afterwards.

Danny Boyle grew up in a working-class family outside Manchester, where, ironically, he had a more conventional Irish childhood than Hickey:

I was brought up a very strict Catholic by my mum, who was from Ballinasloe. The iconography of the saints played a big part in my childhood. I was to be a priest, and went to the Salesian college in Bolton. I was an altar boy for eight years, serving Mass every morning. I remember the parish priest, Father McIvor, always had his slippers on under his vestments because he’d just got out of bed. At fourteen I was supposed to go to a seminary in Wigan. A priest warned me off it. Whether he was saving me from the priesthood or the priesthood from me I can’t be sure.

After that I started getting involved with staging plays at school. You’ll find a lot of people in films, like Martin Scorsese or John Woo, flirted with the priesthood. There’s a lot of theatricality in it, I suppose.

He found his way to the Royal Court Theatre, cutting his teeth as a deputy director on plays by Howard Baker and Edward Bond. He got the job in Belfast because no one would go there: it was the aftermath of the hunger strikes. ‘I’d been there loads of times and it wasn’t frightening at all,’ he says. ‘The BBC didn’t want to appoint a local for political reasons. It was much easier to bring in an outsider, an Englishman, a Brit.’

Boyle had the idea of commissioning three original screenplays from three leading Irish writers, Frank McGuinness, Anne Devlin and John McGahern, to be screened on BBC 2 in autumn 1987. Since Hickey was already working on a film of McGahern’s novel,The Pornographer, Boyle saw him as a natural collaborator.

McGahern was wary. Although it would be his first original screenplay, he had previously worked for the BBC on adaptations of his story ‘Swallows’ and of James Joyce’s ‘The Sisters’. ‘Both were disasters,’ he told me. ‘The idea this time was to get writers and directors from theatre to create work for TV. All we had in common was that none of us knew anything about television.’

McGahern had always been drawn to films, maybe because they were hard to get to see as a child. ‘Our visual senses were very deprived. The nearest cinema was seven miles away. There was a travelling cinema with a tent, but the generator would sometimes break down. I didn’t see my first film until my father took me to Dublin for the All-Ireland final in 1947 and we saw Mickey Rooney and Spencer Tracy inBoy’s Town.’

As a student in UCD he’d queue at the Astor on the rainswept quays to see continental films. He saw Becker’sCasque d’Orseveral times. ‘You can go back to a movie like to a book or a poem. It would be a brave man who would say that almost any novel was superior toMonsieur Hulot’s Holiday.’

McGahern’s screenplay,The Rockingham Shoot, the story of children beaten by a nationalist schoolteacher when they stay away from school to work as helpers on the local lord’s estate during a pheasant shoot, comes from childhood memories, as does all his fiction: the mother dying of cancer inThe Barracks, the small-town claustrophobia ofThe Dark, the bigoted persecution of the teacher inThe Leavetaking.

Growing up in Cootehill, where his father was the garda sergeant, he remembers the British ambassador, Sir John Massey, arriving with all his bodyguards to take part in the annual shoot and ball in the big house at Rockingham. But unlike the children in the film, McGahern was never allowed to go there to earn the half-crown for beating out the birds. ‘The hurt remains. We used to look at the lighted windows from away beyond the main walls.’

The Rockingham Shootbegan as the draft for a story that didn’t work out. ‘The image was always in my mind and wouldn’t go away. The idea of the ordinary life of a new order beginning outside the walls and, in a way, the old order being carried into the beginning of the new order.’

To this teacher, the survival of any trace of Ascendancy ways and the dependence of the village on the estate seems a betrayal of the ideal of a free Ireland. He only has to look out the window to see the gates of the Big House taunting him. Out of frustration and anger he conducts his class like a political meeting so that even a lesson on Goldsmith’sDeserted Villageis turned into nationalist propaganda.

A BBC Northern Ireland flyer for a 1987 series of Irish plays scripted by Frank McGuinness, Anne Devlin and John McGahern and produced by Danny Boyle.

Hickey situated the action of the story in the early fifties with the teacher as a failed Clann na Poblachta election candidate. There is a sense in which he epitomizes the warped nature of much of Irish education of that period. But McGahern has something less specific in mind. ‘The real idea behind it isn’t of any period. It’s that somebody who embraces an idea too literally or too passionately is always a danger to society peacefully functioning and to the natural order of things and to people’s comfort. Lies are the oil of the social machinery.’

The irony is that the teacher is more intelligent than most of the people around him: