Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

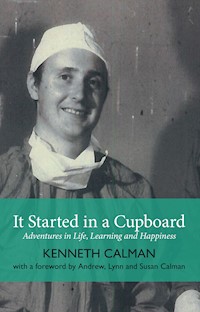

Sir Kenneth Calman's extraordinary life story is based on a passionate love of learning – and it all began with him doing his homework by candlelight in a cupboard of his mum's Glasgow council house. He went on to be at the forefront of three different medical revolutions – oncology, palliative care and the use of the arts in medical education – and to help guide the country through the BSE/VCJD health crisis. As Scotland's and then England's Chief Medical Officer the reforms he pushed through saved many lives by improving both cancer care and the training of doctors. Few people know as much about learning, laughter, health and happiness – or, come to that, sundials, beagles, cathedrals and cartoons. And few people have touched so many lives, especially those of the seriously ill and dying, with quite as much grace, humour and humanity.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 437

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By the Same Author:

Basic Skills for Surgical Housemen (Churchill Livingstone, 1971) An Introduction to Surgical Aspects of Haemodialysis (Churchill Livingstone, 1974) with PRF Bell Cancer Medicine (Palgrave Macmillan, 1978) with J Paul

Basic Principles of Cancer Chemotherapy (Palgrave Macmillan, 1980) with MHN Tattersall and J F Smyth

Basic Skills in Clinical Medicine (Churchill Livingstone, 1984) with C Hanning

Royal Medico-Chirurgical Society of Glasgow: A History (1989) with DA Dow

Healthy Respect: Ethics in Health Care (Faber, 1994) with RS Downie

Invasion: Experimental and Clinical Implications (Oxford University Press, 1984) with M Mareel

Nutritional Support for the Cancer Patient (Saunders, 1986) with K Fearon

Living with Cancer: An Introduction for Patients, Families and Staff (Tak Tent, 1987, privately published) with M Duthie

The Potential for Health (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Risk Communication and the Public Health (Oxford University Press, 1999) Edited with P Bennett

Storytelling, Humour and Learning in Medicine (The Stationery Office, London, 2001)

Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine (Oxford University Press, 2005) Joint Editor with Derek Doyle, Geoffrey Hanks and Nathan Cherny

Handing on Learning: Medical Education: Past present and future (Elsevier 2007)

A Doctor’s Line: Poetry and Prescriptions in Health and Healing (Sandstone Press, 2014)

Afterthoughts (Kennedy and Boyd, 2017)

First published 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912387-66-3

The author’s right to be identified as authors of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted. The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by

CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham

Typeset in 11.5 point Sabon by Main Point Books, Edinburgh

Text © Kenneth Calman, 2019

Contents

Foreword

1 A Cupboard in Knightswood

2 The Tram from St George’s Cross

3 A Surgeon in Training

4 Scotland’s First Oncology Unit

5 Learning from Patients

6 Dean of Medicine

7 Scotland’s Doctor

8 London Calling

9 Mad Cows

10 Make It So

11 The Durham Concerto

12 Me and My Mace

13 The Arts and Health

14 Books and Beyond

15 My Scotland

16 Smile a Lot – It Confuses People

17 Cum Scientia Succurro

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

This book is dedicated to my wife Ann, my three children Andrew, Lynn and Susan and their partners, who have helped and supported me over the years and have given me fun, laughter and love, and to my two grandchildren, Grace and Brodie.

Foreword

Compiled by Susan Calman

ALL THREE OF us Calman children breathed a sigh of relief when Dad told us that he was finally writing the story of his life. For a man who is so well known, there are many things that we have never talked about. To have his memories preserved in the pages of this book means that we can fully appreciate his life and achievements, and my niece and nephew will understand that their Grumps (that’s their nickname for him, not a comment on his temperament) isn’t just a fun-filled man who wears Christmas jumpers: he’s a pioneer and a great man.

Rather than me trying to summarise what we all felt, I asked my brother Andrew and sister Lynn to read the book and then send me their thoughts. They echo my own in many ways.

Andrew noted:

There aren’t too many people who have done quite as much with their life as Dad has with his, yet when I think of him, I don’t think of his achievements so much as the times we’ve spent together walking the dogs, relaxed in each other’s company and putting the world to rights. Even today, those walks mean everything to me

Reading this book made me realise just how much Dad was doing in his professional life while chatting with me about mine. The book is full of references to people, places and events that I remember but did not fully understand at the time, such as Tak Tent meetings at our house, colleagues and friends of his we would bump into, no matter where we were in the world, or seeing him in the news discussing something related to his jobs such as being Chief Medical Officer.

This book has brought back a whole heap of memories of all the places we have lived in, of all the dogs we’ve had over the years and all the various places we have walked them. Significantly, this book connects memories of different stages of my life through each of these dogs depending on where we were and what we were doing at the time. From being a toddler on Wimbledon Common chasing after Bart, our black Labrador – the first of our family’s dogs – to ambling ahead of Ailsa, his slow, snuffling beagle, those walks with Dad have helped shape my past, present and future life, and I treasure them

To this day we all get together on 2 January every year, no matter what else is happening in the world, for a long walk with the dogs. And for all of us it is a chance to connect and relax.

My sister Lynn is the only one of us who has carried on the family tradition of health care. Personally, I faint at the sight of blood so would have been worse than useless in a ward, but she understands Dad’s legacy in a different way.

She says:

There can be few people who have had such an impact on the lives of people living with cancer, both at an individual and service delivery level.

I remember as a child visiting his unit at the hospital in Glasgow every Christmas Day – not realising till much later the impact this had on me. But leading the team by example and being there on the ward was so important to him. Despite his regular absences – evenings and Saturday mornings back in the hospital, conferences and courses all over the world – I think we somehow understood even as young children that what he did was so important for people. The smell of a hospital still reminds me of hugging him when he came home at night

He went above and beyond to be there for patients. The team in his unit was truly multidisciplinary with value placed on the role of everyone. The ground-breaking patient booklets written with patients and nurses are an example of this and were well ahead of the curve of what would now be the standard of care in the NHS. I remember hearing the unit ‘parties’ and skits from my bedroom and thinking whatever they do at work it must be great fun! Back then, I wouldn’t have had any inkling of the strain that poor survival rates and limited treatment options would have placed on the team.

Dad’s influence in cancer care has gone beyond the individual. The 1995 Calman-Hine report was the first comprehensive report on cancer in the UK and set out a radical change in service delivery for cancer patients, a model that is still used today. This has had an impact on millions of people with cancer; its importance cannot be overstated. He believes he is no longer relevant in the area but his impact can still be seen in oncology practice today.

Dad has been an inspiration in what I do and how I do it. I have followed his path to some extent, although I couldn’t match his professorship at 32! I became a nurse and now lead a programme of research in living with and beyond cancer – essentially what the patient-focused care and psycho-oncology, pioneered in his unit, has become – and I am so proud when his contributions are still mentioned at oncology meetings and conferences.

I can’t talk about Dad without mentioning Mum, in her own right a role model – undertaking health promotion research with primary school children in the 1980s that was ahead of its time and latterly chairing a large primary care trust in the north-east of England. Without her support and understanding none of the above would have been possible!

I also remember Christmas Days spent visiting the Oncology Ward in Glasgow. And the memories of those times mean that I still have a deep connection to his work. I’m a patron of the charity that Dad set up, Cancer Support Scotland, and also of Target Ovarian Cancer. I can’t carry on the research work that he and my sister have been part of, but I can help in a small way to carry on the family legacy.

For me, it is the first few chapters of the book that are the most important. I’m named after my gran, Grace, and she looked after me in the house in Knightswood (described in loving detail in this book) while Mum was at work. So much of hers and my dad’s lives were never talked about because it was extremely painful to discuss. The grief over the loss of his father and the struggles that Gran had bringing up two boys on her own are brought vividly to the fore in these pages. It was a revelation to me to finally read the stories and imagine the hardships that the whole family went through. This book has allowed me to know my wonderful gran more as well and that is a priceless, accidental memento.

It’s difficult to find a way to conclude a Foreword to a book, as you probably haven’t read it yet and I’d hate to spoil the journey for you. What I will say is this. Everyone always says that I’m the spitting image of my father and that’s always been a great compliment. After reading the story of his life – and I’m sure I speak for my brother and sister – we are all even more proud to call him our dad.

Andrew, Lynn and Susan CalmanJuly 2019

CHAPTER 1

A Cupboard in Knightswood

I WAS BORN on a day of peace in a world at war. At seven o’clock in the evening on Thursday 25 December 1941, when I came into the world, the BBC’s Home Service was about to broadcast the Christmas Night Troop Service from the Church of the Holy Trinity in Bethlehem. On the other side of the world, on that very day, one of my cousins was killed when the Japanese occupied Hong Kong.

In the Lindores Nursing Home, in the West End of Glasgow, none of that registered. There was no radio in the delivery room, and in any case the news of the fall of Hong Kong had been deliberately held back. To Arthur and Grace Calman, the wider world faded into the background. All that mattered was that their first child had been born, weighed a healthy 7lbs, and they couldn’t wait to take me back home.

Our home at 62 Thornley Avenue was a two-bedroom council flat – what estate agents these days call an ‘upper cottage flat’ – in the west Glasgow suburb of Knightswood. My mother and father had moved there shortly after getting married in July 1939. For the next 55 years, until she moved into a nursing home for the last few months of her life, my mother never lived anywhere else. And as I never stopped visiting her there, and as it’s where I spent the first 25 years of my own life, that house and Knightswood mattered to me a lot. It was my home, and I’m rather proud of the place.

Why? Because Knightswood, which was built in the 1920s, had been properly planned and thought-out, and the answers the planners had come up with chimed in with how people wanted to live their lives. They wanted shops, schools, libraries, churches and railway stations within easy walking distance, so even though they might be living at the edge of the city, it didn’t feel like it. They wanted parks to play in, maybe even with a municipal golf course, pitch and putt greens and tennis courts attached, with the Campsie Fells on the horizon and the countryside just an easy walk or cycle-ride away. Most of all, when they moved out of the inner-city tenements to live there, they wanted their own patch of land too: a 10ft strip of garden in the front, with a waist-high hedge or curved iron railings to separate it from the pavement, and at the back a garden the size of a tennis court.

The estate on which the council built 6,174 houses was carved out of about four square miles of farmland and disused mining works just outside what was then the city’s north-western boundary. All the flats had fitted bathrooms and decent-sized rooms – ‘homes not hutches’ in the words of John Wheatley, Labour’s first Secretary of State for Health, whose 1924 Housing Act provided the financial guarantees councils needed to start building. But there was far more to the estate than that. It had eight churches, because this was still a rigorously Christian society: my parents were both devout members of the Church of Scotland and I grew up to share their faith. There were four shopping centres, each with enough for most families’ daily needs, and six schools, both primary and secondary. At the end of our street there was even a library and a community centre.

Knightswood wasn’t just the biggest housing estate Glasgow built between the wars, but it was arguably the best. On Saturday evenings, from 1939 to 1953, one of the most popular radio shows on the BBC’s Scottish Home Service was a radio soap opera called The McFlannels. It was about a working-class Glasgow family who had originally lived in Partick tenements. When they moved to a four-room flat in Knightswood it was made quite clear that they had ‘gone up in the world’, although some of the characters complained that because it was so remote, commuting to work took too long.

Where we lived, though, that didn’t seem so much of a problem. There was a good bus service, Scotstounhill railway station was only about a quarter of a mile away, and the nearest shipyard on Clyde was just about the same distance again. And when you reached the river, whether you looked left or right, for miles in either direction you’d see shipyards hard at work: great thickets of cranes at Barclay Curle, Charles Connell, Blythswood, Yarrow, Fairfield, and, a mile or so up the river, the famous John Brown yard at Clydebank, where they’d built the Queen Mary and where they would go on, after the war, to build her successors, the Queen Elizabeth and the QE2. In the early 1900s yards like these had produced a fifth of the world’s ships. By the time of the Second World War, that proportion was falling back, but after the lean years of the Depression, the yards were busy again, and so were the other riverine businesses filleted between them: propeller and pump manufacturers, repair yards, engine works and dry docks. During the war, my father worked as an engineer in one of the Scotstoun shipyards. As this was a reserved occupation, he was exempt from conscription, though he also served in the Home Guard.

Sometimes, when I look back at my parents’ photo albums from those days, it’s hard to imagine that there ever was a war on. Certainly there are no signs of it in the pictures they took on holiday in Largs in June 1940. France might have fallen, and many people thought Britain might be next, but that wasn’t going to stop Arthur and Grace Calman going on their first proper holiday after their honeymoon, walking down the promenade, watching films in the Viking Cinema, eating ice cream, and smiling for the camera. They were back in Largs again exactly a year later. The war was still going badly, but again there was no hint of that in the family photo album, just as there wasn’t in the photographic record of their summer holiday in 1942, when we stayed in the Station House at Hopeman, on the Morayshire coast, after travelling to Inverness on the sleeper. By this time, I was six months old. My dad wrote a poem about me:

Six months ago on Christmas day

God filled our hearts with joy

He gave to us love’s precious gift

A lovely baby boy

So Kenneth Charles we christened you

And will our vow fulfil

That with God’s help your mum and dad

Will keep you from all ill

And yet the war was there, all the time, all around them. Even in those happy family snaps, it creeps in around the edges. Take my first appearance in the family album. It’s 23 May 1942 and there I am, being proudly shown off to my adoring gran in our back garden. Again, at first glance, it seems as though it belongs in peacetime: but look again at the garden and you can see that it has been given over to growing potatoes. By 1941, thanks to the Dig For Victory campaign, and the songs and recipe books of Captain Carrot and Potato Pete, Britain’s food imports had halved to 14.65 million tonnes. Some 10,000 square miles of gardens and neglected spaces had been taken over by vegetable growers. At No. 62 Thornley Avenue, we were doing our bit too.

In some of the photographs, in the middle of the potatoes is the grim hump of an Anderson shelter. Again, there’s nothing unusual about that: 2.1 million of these corrugated galvanised steel shelters were half-buried in Britain’s gardens, with most resurrected in peacetime, as ours was, to serve as a garden shed where we also kept our bikes. But nine months before I was born, in the middle of the Clydebank Blitz the shelter had its use. I might even have been conceived in it!

On the night of 13 March 1941 the first of three waves of German bombers flew west over our house. They’d already done their aerial reconnaissance, and you can see the targets marked out on their largescale (1cm:150m) briefing photographs. On them, Knightswood is unmarked, the neat geometry of its streets undisturbed by parked cars or indeed vehicles of any kind. The real targets were in Clydebank, just over a mile to the west. The giant Singer Sewing Machine works, then largely given over to munitions work (they made Sten guns), was the biggest one, but John Brown’s shipyard wasn’t far behind: this was, after all, where the British battle cruisers HMSHood and HMSRepulse – both sunk, with appalling loss of life, later that year – had both been built. Beardmore’s engineering works was badly hit, as were the Admiralty oil storage tanks at Kilpatrick, and a huge timber yard at Singer’s was lost – the last two adding immeasurably to the fires that earlier incendiary bombs had started. Before the Clydebank Blitz there had been 12,000 houses in the town. Only seven were unscathed; 4,300 were destroyed or beyond repair. In the two-night bombing raids of 13 and 14 March 1941, 528 people died in the concentrated carnage of Clydebank, and a further 650 in Glasgow.1

It’s odd, isn’t it, the things you never ask your parents? While they were alive, I never remember asking either of them what it felt like as those German planes roared overhead under a full ‘bomber’s moon’ and the Drumchapel ack-ack guns opened up – whether they were frightened and stayed in the Anderson shelter until the all-clear sirens sounded, or whether they couldn’t stop themselves going outside to look at the flames devouring Clydebank. It wasn’t as if they were far from the danger themselves. Some of the earliest bombs in the raid fell on Knightswood – on houses in Alderman Road, Baldric Road and Kestrel Road. But it was the eight foot-long cylindrical 1,000lb landmine that landed on Bankhead School that did the most damage. Witnesses reported hearing a ‘flapping’ sound, looking up and seeing it swing down by parachute, hitting the school roof, sliding down the slates and dropping down to the playground, where it exploded. The blast destroyed almost the whole of the west wing of Bankhead School, which at the time was being used as a first aid post, fire station and ARP (Air Raid Precaution) centre. Thirty-nine people were killed, including 21 auxiliary firefighters and two teenage messenger boys. The fire burnt until dusk the next evening. St David’s, where we all went to church, was damaged in the raids too, but so slightly by comparison to the horrors at Bankhead School – which my brother Norman and I subsequently attended – that I can’t remember anyone ever mentioning it.

People forget just how long the war overshadowed the peace that came in 1945. Norman was born that year, but even by the time he left Bankhead school in the mid-’50s, ten years after the end of the war and 15 years after the bombing, they still hadn’t replaced the gym hall or the canteen. Rationing lasted almost as long: it only ended in 1954. Years later, when I was Chief Medical Officer for first Scotland and then England, I used to tell my political masters that if they really wanted a healthy population, they should bring it back. Britain’s wartime diet may have been deeply unpopular, but the country has never had a healthier one.

That, then, is a snapshot of the place and the time I was born into. But before I got any further, I should introduce you to my parents and the rest of my family. I loved my Dad. I loved my Mum too, but she wasn’t the one who played football with me in the back garden, put me on her shoulders to watch Rangers at Ibrox, taught me to play golf on Knightswood’s municipal nine-hole course, or made wooden toys for me at Christmas. Dad was fun to be with, and he had a great sense of humour. He used to play a game called Mr Bumble, where he dressed up and sang, ‘My name is Bobbie Bumble, he doesn’t mind a tumble, but up he jumps, and rubs his bumps and doesn’t even grumble’ and fell on the floor. It always made me laugh anyway. After the war, when work started to dry up in the shipyards, he got a job as a mechanic at MacKinnon’s, a local textile manufacturer. I always looked forward to seeing him. To this day, I can remember listening out for him as he walked home along the street, whistling the first few bars of the Woody Woodpecker theme tune.

He was the youngest of eight children (and two who didn’t survive childhood) and as all of them had children of their own, I had plenty of Calman cousins. The one I never knew was Charles, who was killed by the Japanese on the day I was born. He was the son of my uncle Alex, who had moved out to Hong Kong, where he managed a shipyard. I never knew my paternal grandfather either, but he was the one who brought the family from Dundee, where they lived at Lochee, to Glasgow early in the previous century. The word Calman is Gaelic and means a dove or pigeon, and the family, and the name, have an interesting history.2 They lived in Partick, a district in Glasgow near the Clyde. My father attended Hamilton Crescent School, which he left when he was 14 to work in the shipyards. I have a Certificate of Merit for him from his final year, where his subjects included Laws of Health, Civics and the Empire.

My mother’s family were also very close to me. She had been born Grace Douglas Don and her sister Cathy lived close by in Knightswood with her family and my Gran Daisy. Her brother and his family lived for a long time in the South Ayrshire village of Dailly, near Girvan. At one time he had a chip shop in which I occasionally helped out: not bad training for a future Chief Medical Officer! My father’s brother, Charles, and his family also lived in Ayrshire: he was a Hoover salesman with great patter and his key phrase when going anywhere was ‘The sky’s the limit!’ His daughter Doreen had a special dance which she demonstrated at weddings to the tune of ‘Salome’ with great effect.

Mum was devoted to my father. She wasn’t as much of an extrovert as him, and if you didn’t know her you might even mark her down as being quite shy, but they seemed to complement each other. She had been secretary to Sir Hugh (later Lord) Fraser and was an excellent typist and typed my PhD thesis. Her mother lived in Knightswood along with her sister, my auntie Cathy, so there was plenty of family support on hand to help in bringing up me and my brother Norman. Beyond the family, there was the church and the Women’s Guild, and, after the war, the community centre at the end of our street, where she won prizes for her baking, sewing, and special tablet – a wonderful fudge. She loved the cinema too, and would regularly head off with my father to catch the latest shows at the Ascot, the Rosevale and the Vogue. My bedroom was just across the hall from the sitting room, and I can still remember crawling there like Wee Willie Winkie, unable to sleep and wanting a story, as my babysitters Moira and Norma sat on the sofa in front of a coal fire banked with dross, ready to last through till morning.

I’ve always been a hoarder, so I’ve held onto quite a number of things from my childhood that I hardly remember or don’t remember at all. My mother’s baby book, for example, informs me that I first slept through the night aged ten months, and that I started walking about the same time. By 18 months, I could say ‘Please, mummy’, ‘Thanks’ and (very polite) ‘Pardon me’. On Monday 10 February 1947, I first went to school, and apparently liked it. My dad made me a wooden rocking chair, in which I was photographed when I was one: I’ve still got it, and my children and grandchildren have sat in it, just like I still have the three cut-down hickory golf clubs he used to teach me on the nine-hole Knightswood municipal course (threepence for children on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons). I still remember the sign on the clubhouse, ‘Each player must have at least 3 clubs, one of which must be a putter’. When I was eight, and we were on a family holiday in St Andrews, the two of us played all three major courses, including the Old Course, which probably isn’t possible to do now. I’ve also still got my father’s helmet and booklet from his Home Guard days, bits of blackout material, the airplane hangar he made me for Christmas in the war when toys were luxuries beyond compare. I can tell you that when I saw the Scottish Cup Final on 20 May 1944, I sat in Section K, Row L, on the East Stand, though I can’t tell you anything else about the game. And the first time I saw Rangers play a foreign side was on 25 November the following year, when they played Moscow Dynamos – who caused controversy by taking to the field with12 players. It was a Wednesday afternoon kick-off, but still a stonking 10 shillings a ticket.

Without anything I’ve hoarded to prompt my memory, however, I can still remember the big freeze in 1947, when the snows were so deep that the Great Western Road – the A82, the main road to Loch Lomond – was closed, and we could sledge down a hill and all the way across it. And I can remember Hogmanay in the days when the Clyde was rammed with ships, and the sound of their horns at midnight welcomed in the New Year. In 1948, I remember the huge family reunion we had in Troon, when uncle Alex and his wife Laura finally came back to Scotland from the Far East. He had been captured after the fall of Hong Kong in which his son had been killed, and spent the rest of the war in appalling conditions in Japanese prisoner of war camps. By the time peace came, he was completely emaciated, and had no idea what had happened to his wife: mercifully, she had somehow managed to escape to Australia, where they finally met up again.

Significant or trivial, but all mixed together – that’s how memories flood back when I reflect on my childhood. Firing up the memory neurons in my brain, a whole variety of unrelated scenes and facts from childhood leap across my synapses. My mother tying my laces and asking me to run down and see what food was in the shops (‘There’s mince in the butcher’s’ I would announce to the whole street on those comparatively rare days when there was). Long games of marbles that we’d play on roads empty of all traffic apart from the occasional horse-drawn coal cart. Listening to Children’s Hour on the radio. Cycling for a picnic in the Bluebell Woods of (then undeveloped) Drumchapel. Playing interminable games of football where we used the ‘pig-bins’ (where food waste was kept to be fed to pigs: another hangover from wartime rationing) as goal-posts. Long after I ever needed to know it, I can recite my Co-op number – 251214 – or the best-ever Rangers line-up (Brown, Young, Shaw, McColl, Woodburn, Cox, Waddell, Gillick, Thornton, Finlay and Duncanson). Shards of my childhood are buried in memories like that, or in the print of the football programmes I used to collect, or in the pages of the ten volumes of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia, which I was given for my seventh birthday.

But there’s one memory from my childhood that overshadows all others. On 25 June 1951, Norman was looking out of the window hoping to see Dad coming whistling up the street when he saw a policeman opening our gate. Seconds later there was a knock on our main door, at the side of the house. Mum went down and he told her that she’d better get round to the Western Infirmary, because my dad had just been taken there. She ordered Norman and me to go out and play and went off to find Mr Kirkland, one of only two people in our street who had a car, to ask if he’d take her to the hospital.

We were playing football in the next street a couple of hours or so later when one of the neighbours came to find us and told us that we were wanted back home. He didn’t say why, but I knew there was something wrong as soon as I turned the corner. There were three cars, all parked outside our house. Norman, being only six, didn’t realise that spelt trouble. The two of us went up the stairs and into the lounge. It was packed out with relatives: Mum’s sister, Auntie Cathy and her mum, our Gran, had walked over from Upper Knightswood. On my father’s side, Auntie Dove and Uncle Tec had driven over from Newlands, Auntie Jean and Uncle Jimmy had come from Baillieston and Aunt Ellen and Uncle Willie from Rutherglen. They all looked up at us with pity in their eyes. I forget who it was who told us that my father had just died of a heart attack.

Dad had been to see the doctor that morning about something quite trivial – a painful toe that was probably gout. Yet as he was being examined, he had symptoms of a heart attack. The GP told him he should go straight to hospital. He took a bus to Western Infirmary, where he collapsed and died at the porter’s gate. He was just 41.

For most of my life since that day, I’ve wondered what it would take to make a heavy smoker like my father stop. When I was Chief Medical Officer, working out an answer to that question, that would apply to everyone, was a key part of my job. How do you stop someone smoking? Is spelling out the risks enough or will smokers just ignore the mountainous accretion of evidence that it’s bad for them? At what point do you give up on efforts to try to persuade them – or should you? What, in short, works? And would it have worked for Dad? That’s one of the biggest ‘what if’ questions in my life – and if anything, it has grown even bigger in my mind as I have grown older. As the years have gone by, I actually miss my father more and more. I think of the joy my wife Ann and I have found watching our grandchildren Grace and Brodie grow up. I know he would have felt that same delight in our own children – Andrew, Lynn and Susan.

My father had died only a year after the first definitive evidence of the link between smoking and lung cancer emerged.3 Smoking was not only socially acceptable, but, hard as it is to understand now, the first government information campaigns actually encouraged it. In 1917, the Pipes and Tobacco League sent tobacco to soldiers and sailors on the frontline, arguing that it was good for their health as well as for morale. Six million men who served in the First World War were introduced to smoking when they joined up, and free tobacco only encouraged their addiction. Such attitudes carried on into the Second World War public health education too: a wartime ‘Blood donors wanted’ poster featured an injured soldier being tended by his comrades while contentedly drawing on a cigarette. The 1947 Budget even went so far as issuing pensioners with tobacco vouchers to offset tax increases.4

Back then, of course, I knew nothing about any of this, or that this was one of the main directions my life would take. I was just a nine-year-old boy shattered by grief. I now have close on 70 years of hindsight, and I occasionally think of how easy it would be for that nine-year-old boy’s world to collapse. But it didn’t. We were surrounded, I can now see, by love. It was there in my primary school teachers (Miss Bissell and Miss McKellar), despite having classes of 50-plus to contend with, taking the time to encourage me. I knew they cared. When school ended on my first day back, one of them came to me, bent down and did up the buttons of my coat. She’d never done that before – no teacher had – but as she did, I saw tears welling in her eyes.

And it wasn’t just her. In searching through my archives, I came across a small autograph book. The biggest cluster of contributions to it from friends and relatives came in July and August 1951 and include signatures they knew would mean a lot to me, like those from Rangers and Queen’s Park football players. It’s as if my family, friends and neighbours were trying to take my mind off my father’s death and giving me other things to think about. We had always been a close family, and my father’s death didn’t change that: his family always remained close and supportive, just as my mother’s did.

Then there was the community centre, less than 100 yards away at the end of our street. After it opened in 1950, it was where about 20 or 30 of us would go in the years before we had a television of our own, to sit in front of the 12-inch screen and watch programmes like What’s My Line?. Communal television-watching was then fairly commonplace, as it was only after the Queen’s coronation that we, along with millions of other families, got a set of our own. We watched the coronation on the tiny set hired for the day and placed in the church hall at St David’s. We had packed sandwiches and taken them to church, where the minister had led a special coronation service before we went into the church hall to watch events at Westminster Abbey. In my surprisingly neat 11-year-old’s copperplate, I wrote up what happened next:

We saw our beautiful Queen Elizabeth crowned. As well as seeing the television, we got sweets, balloons, lemonade and tea. At night, we went round the parks watching the fireworks and seeing bonfires. At last we had to go home, but what a lovely day it had been.

Generally, though, it was at the community centre that most of our social life took place. They held Scottish country dancing classes there, and there was a room in which Miss John’s Orchestra rehearsed (with me on drums: my favourite was The Radetzsky March by Johann Strauss). There was a library there too, and both my mother and I used it a lot: her to borrow romantic novels, me to work my way through books like Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series or Angus MacVicar’s The Lost Planet. Before the war, there had been plans to build a swimming pool there too, but the council had run out of money and the site was fenced off. This – along with the fact that it was a shortcut between our house and Bankhead primary school half a mile away and that we could easily climb over the fence – meant that the long-abandoned building site became our unofficial adventure playground.

My father’s death meant that looking after the garden now became my responsibility, and as I grew older and stronger I used to help out with neighbour’s gardens too, which provided me with a bit of pocket money. While I was at school I used to help my uncle, who made and repaired watches and clocks, for a couple of afternoons each week. Usually, this involved taking repaired watches to the shops, or doing odd jobs. Sometimes, however, I cleaned the clocks and began the process of rebuilding and resetting them. It was fascinating, and to this day my brother Norman keeps the small business going. For me, however, the key thing was my interest in time; how important it was and how it should not be wasted – something I still feel strongly. It also underlies my interest in sundials, which continues to this day. I had plenty of hobbies – making balsa wood model aeroplanes, stamp collecting, and photography among them – but my real priorities were elsewhere: church and the Boys’ Brigade, music and study.

It is hard to underestimate how important Christianity has been to me, not only now, but in my teenage years too. Even when my father was alive I’d attended Sunday school, and later joined the Scripture Union, went to their camps, and won a Young Worshippers’ League prize for attending a Sunday service every week for five years. St David’s was close to our home and its Christmas Eve midnight service still lingers in my memory – and not just because my birthday started when it ended. At midnight, as we sang ‘Still the Night’, the lights were dimmed and left only the cross lit up with a star on a dark blue velvet curtain background.

The church always had a series of powerful ministers, and the one I remember most was the Reverend Eric Alexander, who was at St David’s for four years before going on to be minister at St George’s Tron church in the centre of the city. I saw him as a role model, and even briefly contemplated being a minister. In April 1955, I had, after all, seen the most impressive evangelist in the world. The first night Billy Graham preached at the Kelvin Hall, on 21 March 1955, 16,000 people turned up. ‘But when I gave the Invitation at the end of the sermon,’ Graham said afterwards, ‘not a soul moved. I bowed my head in prayer, and moments later, when I looked up, people were streaming down the aisles, some with tears in their eyes.’5 It’s hard these days to convey the effect Billy Graham had on Scotland that year. Even the statistics, though verifiable, seem completely implausible now: audiences of 2,647,365 people in the entire All Scotland Crusade, church attendances in Glasgow 50 per cent higher at the end of the decade than before he arrived, 100,000 people at his farewell rally at Hampden (and, in those more ordered and respectful days, not a single one of them on the pitch), a worldwide audience of 30 million for his Good Friday rally at Kelvin Hall. But those figures don’t even begin to explain what it felt like to watch, as I did, Billy Graham’s rally at Kelvin Hall. This was, remember, the biggest exhibition hall in Europe, and it was packed. Packed with people who hung on the preacher’s every word, whose lives were changed by his message. I was already sure of my Christian faith, but that Kelvin Hall rally had a profound effect on me all the same.

All through my teenage years, the Boys’ Brigade was a hugely important part of my life. ‘The best way to enjoy yourself in the Life Boys,’ the membership card of its junior branch advised, ‘is to put your heart into everything.’ I did too, moving up into the Boys’ Brigade proper and then ascending the ranks until I was 18, when I was a staff sergeant. (Years later that ascent continued, as I became first President of the Glasgow Battalion and then UK President of the Brigade in 2007. Little did I know that my future wife, Ann, was also heavily involved in the organisation.)

The Boys’ Brigade’s Glasgow credentials are impeccable (it was founded there in 1883 by Sir William Smith), but for me it had many other attractions. Its Friday meetings were where my folk singing began and my limited acting talents found their first stage. Working towards the various badges – woodwork, birdwatching and so on – they taught me practical skills I might not have acquired anywhere else. For my first aid, I learned to master the basic skills of bandaging and resuscitation, and although I never thought so at the time, in hindsight that might have been the first glimmer of an interest in a career in medicine.

But of course, I didn’t think like that. The 14-year-old corporal in his Boys’ Brigade pillbox cap, assiduously learning about marching and playing the drums in its pipe band (for which Norman played the bagpipes) didn’t have a clue what career he wanted to pursue. I followed the old Life Boy mantra and put my heart into everything they taught me, and ended up as the troop’s best-drilled recruit and winner of the trophy for ‘best all-round boy’. I mightn’t have known what I wanted to do with my life at that stage, but the Boys’ Brigade gave me a sense of purpose. Its motto of ‘Sure and steadfast’ could just as easily have been mine too: I shared its Christian values and aims (‘the advancement of Christ’s kingdom among Boys and the promotion of habits of obedience, reverence, discipline self-respect and all that tends towards a true Christian manliness’) and looked forward to the Bible study sessions that were every bit as important a part of our Sundays as were the parades. These were, as Billy Graham’s crusade made clear, different days: stronger in Christian faith than our own. Where St David’s had six Boys’ Brigades squads in my time, there now isn’t even one.

During the week, I wore another uniform: the navy blazer of Allan Glen’s. This was a remarkable school, founded in the middle of the 19th century by a successful Glasgow businessman who left an endowment ‘to give a good practical education and preparation for trades or businesses, to between forty to fifty boys, the sons of tradesmen or persons in the industrial classes of society’. It did a lot more than that. Over the years, it established a reputation as being Scotland’s best school for teaching science, and the roll call of its eminent former pupils would prove the point. One of the most famous was the architect Charles Rennie Macintosh, and when I first started thinking seriously about my career, I thought that I might try to follow in his footsteps.

At Allan Glen’s I developed a great interest in science and technology, as might be expected. But the arts were also important to me, especially music, and I sang in the school choir. Through one of my longstanding friends, Andrew Dobson, I was introduced to classical music and bought my first records, Finlandia by Sibelius and Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Andrew and I keep in touch and he still sends me terrible jokes. Painting was also important at school, as was pottery, woodwork and metalwork. I loved making things. This was also when I wrote, in neat italic handwriting, and then bound my first book, ‘The History of Flight’. I still have it at home.

Although I had won a bursary to Allan Glen’s, money was still tight – in fact, there wasn’t any coming into the house apart from a small widow’s pension. So my mother began to take in boarders, two at a time, who were training to be physical education teachers at the nearby Jordanhill College. She replaced her double bed with two singles and the two students took over that bedroom. Norman and I shared the other one. Mum slept on a pull-down bed in the lounge. When I look back and think of what she did for us all, as a single mother bringing up two young boys, I am overcome with gratitude.

The only problem was that our two-bedroom flat was completely full. There wasn’t anywhere for me to do my homework. After making us all a meal, in the evening mum would put her feet up in front of the television. The students would either work in their own room or join her in the lounge. Either way, there wasn’t anywhere else I could get out my books and study. But I wasn’t going to be put off easily. To the right at the top of our stairs, between the bedroom and the lounge, there was a small cupboard space. Technically, it was a walk-in cupboard, because it had a door and you could walk in, although it was only four-foot deep and little more than the width of the door. There was a waist-high shelf at which I could sit and, using it as a desk, spread out my books while everyone’s coats and jackets hung on hooks behind me. There was just one drawback; the walk-in cupboard didn’t have an electric light, so I used candles placed in a tin box. And that is where it all began, my learning and writing, both of which have brought me great happiness.

I have kept all my school exercise books, along with timetables, reading lists and even exam papers for my 1959 Scottish Higher Leaving Certificate (I’d find them impossible to do now). And as I take them out of their box, glance at the school’s coat of arms (two compasses above a set square) on the cover, I find it easy to imagine the years dissolving and being back at 62 Thornley Avenue, my younger self beginning to learn the basics of chemistry, calculus, trigonometry or dynamics in the soft, flickering candlelight.6

Allan Glen’s widened my horizons in other ways too – sometimes painfully. Rugby was the sport of choice at school, and my height (or lack of it: 5ft 3¾ins is the tallest I’ve been) meant that I was a natural pick as a hooker. In those days, the rules for scrums were different, and hookers were allowed to swing forward and into the opposition pack to retrieve the ball. I was reasonably good at this, though I did have some accidents, and my nose was broken twice. While I was struggling with my rugby, my cousin Jimmy Docherty (JT Docherty) was being picked to play for Scotland. In 1955, in his second match, he scored a drop-goal in the 14-8 victory over Wales at Murrayfield.7 His father, another Jimmy, who married my father’s sister, had the distinction of playing football for both Rangers and Celtic. Like my own father, my cousin died much too young.

Even before I went to Allan Glen’s, at weddings and other family gatherings, I’d often be dragged out to sing songs such as ‘Over the Sea to Skye’ or ‘If I Can Help Somebody’. I also became interested in folk music, both Scottish and American, and decided to learn the guitar. I couldn’t afford to buy one, so I made one from a kit. I played skiffle music with a group at the Boys’ Brigade and expanded my folk repertoire by cutting out and learning the learning the songs published each week in the Glasgow Bulletin newspaper. My hero was Lonnie Donegan.

What with music, sport, the Boys’ Brigade and homework, my teenage years at school were satisfyingly busy. But as I moved into my last year, I still hadn’t got a clear idea of what career path I should be aiming at. And here my memory, normally so clear, lets me down. All I remember is that the Calman cousins were having one of our regular get-togethers when the subject came up. I can’t remember who was there, or whose house we were in, only that I told them I was thinking about studying engineering.

‘Really?’ said one of my older cousins. ‘What about medicine? Have you ever thought of that?’

Everyone else in the room seemed to think it was a good idea. Why, I don’t know: it wasn’t as though there were any doctors in our family and I didn’t even know anyone who was one. Against that, at Allan Glen’s I’d had as good a secondary education as any working-class Scot could hope for. I’d worked hard and conscientiously. So why not?

CHAPTER 2

The Tram from St George’s Cross

I SOMETIMES TELL people that I got my wife off the back of a lorry, and it’s not a word of a lie. Towards the end of January 1960, Glasgow students were planning their annual Charities Day Parade. Although the tradition has died out now, back then it was a huge carnival – an ‘invasion’ of the city centre in which lorries were turned into carnival floats and packed with students in fancy dress shaking collecting cans in shoppers’ faces. As well as the lorries, there would be a surreal march-past of pipe bands, followed by students dressed in homemade costumes as knights, ghosts, animals and clowns. The parade would wend its way through the city centre towards a viewing platform where it was inspected by the university’s Charities Queen, sometimes with the Lord Provost in attendance. As it passed, onlookers would lob pennies at the passing floats or put coins in the students’ collecting tins.

Back then, I was playing banjo in an eight-piece jazz band, having moved on from the guitar. This made sense: musically, because these were the days of Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, and the Clyde Valley Stompers; financially, because we were paid the heady sum of ten shillings a night. One of the boys in the band was going out with a girl who was a trainee teacher at Jordanhill College. For Charities Day on 30 January, she and her friends decided that they wanted to dress up as flappers and dance the Charleston on the back of a lorry that would join the big parade to George Square before peeling off to collect money in the suburbs. They needed us to provide the music as they danced round the city. First, though, the lorry had to be decorated with streams of coloured paper, they had to meet us, and we had to rehearse.

So that’s why, in a lorry depot at the bottom of University Avenue on 29 January 1960, I met the woman who would become my wife.

‘Are you one of the dancers?’ I asked hopefully.