Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

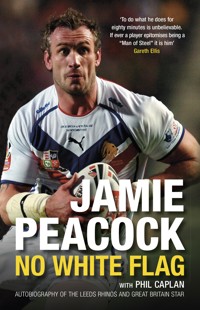

Jamie Peacock is known and respected as one of the most powerful and redoubtable forwards in world rugby. The inspirational skipper at Bradford Bulls until 2005, when he helped them claim the Super League Trophy, the 2003 Man of Steel is now a key figure at hometown club Leeds Rhinos, who he helped to the title in 2007. Having just led Great Britain to their first Test series win in fourteen years, he is also set to captain England in the much-anticipated 2008 World Cup. Coming from a forthright Yorkshireman, this autobiography will pull no punches in describing rugby league as Jamie sees it. Replete with opinions and anecdotes, it is essential reading for anyone with an interest in the modern game. This new paperback edition is fully updated to include the 2008 Rugby League World Cup.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 601

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Faye and Lewis – supporters supreme

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No man is an island, especially in a team sport and my story has been fashioned on the back of the selfless commitment of others.

Thanks must go to school mate Andy Lightfoot without whom there might have been no tale to tell. If he had not given me a letter to take home about my local rugby club, I may never have found the rugby league family. That introduced me to Stanningley ARLFC and, in particular, Mark Adams, Scott Denevan, Darren Robson and John Darby who all played a massive part in shaping my future. At Wollongong University, I was indebted to Chris Bannerman and David Boyle, while coach Greg Mackey gave me the kick up the backside I needed, although I didn’t know it at the time. I have been fortunate to come under some superb coaches who have guided my career and I will be eternally grateful for the patience taken and knowledge imparted by Matthew Elliott, Brian Noble, David Waite, Steve McNamara and Tony Smith. Conditioners Carl Jennings and Martin Clawson made sure that my fitness and strength matched my desire. Everyone who follows a sport needs role models and, if you are a player, mentors. In my early days I had a gang of five who invested a great deal of time on and off the field to guide me in the right direction, whether they knew it or not. To Brian McDermott, James Lowes, Mike Forshaw, Scott Naylor and Bernard Dwyer, thanks for the perfect apprenticeship. Everything I have achieved and experienced has been because of some really special players who I have been privileged to either stand alongside or oppose. Those who have meant the most to me, for a host of different reasons, know who they are but all rugby league players are a breed apart and I respect their bravery and skill. Without the incredible support of the fans of Bradford, Leeds and Great Britain, the deeds would have had little meaning.

When putting pen to paper, Phil Caplan’s dedication and ability to pull together the events and anecdotes was invaluable. I am extremely grateful to Richard Lewis for his foreword and his stewardship of the sport during the time I have risen in it. Dave Williams of the excellent rlphotos.com was responsible for the bulk of the pictures. Thanks also to the editorial and marketing staff at Stadia who have been incredibly supportive of the project from proposal to print, especially Rob Sharman, Stevie Holford, Lucy Cheeseman and Reuben Davison. Peter Smith kindly aided with the proof reading.

Grandad and Nana Gray were incredibly supportive and inspirational during the tough early years when I was trying to make it. My sisters, Amie and Sally have sometimes had to live in the shadows but never as far as I am concerned and have shown great fortitude to put up with me being grumpy all the time. Mum and Dad have been constantly there for me in so many ways and I will always been exceptionally appreciative. By their example of honesty, loyalty, diligence and courage, I got the best possible upbringing and life lessons. Two of the most important influences are my immediate family. Faye has continually kept me grounded and made sacrifices for my career. I cannot thank her enough for her love through all the ups and downs of my turbulent journey. Lewis has given my life perspective; he never fails to make me laugh and smile – no matter what the result.

PHOTOGRAPHIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Plates 8, 10-11, 14-15, 17-18, 19-23, 25-27 and 30-31 supplied by Dave Williams, rlphotos.com; plate 9 courtesy of Ian Beesley, www.ianbeesley.com; plate 29 courtesy of Andrew Varley. All other images are from the author’s own collection.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements and Dedication

Foreword by Richard Lewis

one

It’s Not All Fairy Tales

two

No Pretensions Or Expectations

three

Via Wollongong and Featherstone

four

The Bull Begins to Rage

five

On Firmer Footing

six

Dirt Tracker to Rolls-Royce

seven

At Last the Aussies

eight

World Champ and in the Depths

nine

Hand of Fate

ten

The Best Teams Won

eleven

‘Unbreakabull’, ‘Formidabull’, Sensational

twelve

Frustration at Home

thirteen

Compensation Abroad

fourteen

Confounding the Doubters

fifteen

A Fitting Climax

sixteen

No End in Sight

Career Statistics

Plates

Copyright

‘The desire in the boy is phenomenal – he wants to get better. He asks questions, works very hard and will continue to improve. Five years ago, when he came to the club, he couldn’t catch a ball.’

– Bradford coach Brian Noble at the end of the 2001 season as the Bulls take the Super League crown

‘I remember sitting on a hillside at Siddal watching his game and thinking: “I don’t know how we are going to make a player out of this guy.” But he had something and he has made himself a player. He is very determined and very ambitious; he loves a challenge. Nobody will say a bad word about him to me. He’s a terrific bloke and a terrific player.’

– Brian Noble’s assessment as Jamie Peacock prepares to leave Bradford in 2005

‘He’s been enormous for us pretty much all year, the backbone in many ways. On and off the field he has a big influence in the dressing room. We have some great leaders and he is one of them. He can look knackered for long periods of time and still go out and be effective, he’s got that ability. You think he’s absolutely gone and he gets up swinging. You can’t take into account his body language too much; I’ve learnt that over time.’

– Leeds coach Tony Smith, now the Great Britain supremo, as the Rhinos qualify for the 2007 Grand Final

‘To do what he does for eighty minutes is unbelievable; if ever a player epitomises being a “Man of Steel” it is him. He is massive for us. Every time we need someone to take the ball up, he is there. It can’t help but be inspirational.’

– Gareth Ellis, Leeds and Great Britain teammate and fellow ‘Golden Boot’ nominee, 2007

FOREWORD

I was delighted and honoured to be asked to write this foreword. Jamie Peacock is someone I have come to know and admire enormously. He is one of those people who you sense is a natural leader, from the moment you first see them play.

Once you meet him away from the pitch and start to get to know him, it is obvious that the same drive, willingness and enthusiasm he shows in his profession apply equally to his life. A thoroughly well-rounded individual and genuine man, he is a great example to everyone within rugby league and, indeed, outside the sport.

He has shown beyond any doubt that he is a supreme, world-class performer and an outstanding general in rugby league’s most competitive and challenging environment, the international game. Since assuming the captaincy of Great Britain in 2005 he has consistently proved himself against the world’s best players and emerged with great personal credit from virtually every contest he has been a part of, even if his team has not always been victorious.

Jamie displays outstanding courage and fortitude in battle and enjoys widespread appreciation from fellow players who compete alongside him at Great Britain level, for his club side Leeds Rhinos, and with Bradford Bulls before that.

However, to his immense credit, he is far more concerned with the team ethic and earning the respect of those around him, rather than personal accolades. His primary motivation comes from setting the right example to teammates, while also maintaining his fierce winning attitude and superb professional standards.

Jamie is a true gentleman and the perfect ambassador for his club and code. Despite his elevated status as an international sportsman, he has shown a strong commitment to the values which ensure that leading rugby league players always remain accessible to their supporters and followers.

The assistance and support he offers to his former amateur club, Stanningley, is clear proof that he retains a strong connection with the community that he grew up in. He is also a devoted family man with a genuine social conscience which, in all, makes him an excellent role model.

Jamie’s pathway to his current status as the world’s best forward and skipper of his country did not begin in the conventional manner. His transition from academy to first-team player was far from smooth and he was asked to play in the Australian lower leagues in order to prove himself. Since he successfully rose to that challenge and overcame numerous other setbacks along the way, he has gone on to win every domestic trophy available as well as the prestigious individual ‘Man of Steel’ award.

Jamie looks set to achieve even more in his already distinguished career and players, coaches, match officials and supporters throughout the game will be genuinely delighted to see him enjoy further success. They know he will have truly earned such moments of triumph. I wish him well.

Richard Lewis

Executive Chairman

Rugby Football League

1

IT’S NOT ALL FAIRY TALES

I didn’t think I’d ever forgive him at the time, but now I can see that Matthew Elliott was right. We trained in the pouring rain near Old Trafford on the day before the 1999 Grand Final and I was desperate to know if I would be playing in the big game the following night. I’d forced my way into the Bradford side that year, mainly off the bench, and had a couple of good games against St Helens, our opponents for the title, in the lead-up. But during that last week of preparation I had the lingering feeling that I was going to be the one to be left out. As the intense, hour-long session ended, I said to former Great Britain international – and one of my dressing-room mentors – Brian McDermott that I really needed to know if I was going to be involved and what he thought my chances were. It was set to be my first major rugby league occasion and I was anxious for some peace of mind. In his typical, honest manner, McDermott blithely said, ‘Well go and ask him then.’ Matthew looked at me and bluntly confirmed my worst fears; he was a great technical coach but that was poorly handled – communication was not his strong suit, especially with me, probably because I was relatively new to the first-team set-up. During the regular season, I had been about to get on the team bus to go to Saints when he told me not to bother as I wouldn’t be playing and that had devastated me. When you are involved in a team sport, especially one where the giving of your all is a prerequisite, being left on the outside is a desolate feeling.

My mood wasn’t helped by former teammate Danny Peacock, who I had never really seen eye-to-eye with. There is a dressing room pecking order – even among Peacocks – and there always should be in team sports. I was abiding to it at Bradford, which went some way towards helping me gain the respect and assistance of the senior players, which I needed. He took the distinction too far, though, and just saw the younger guys as fair targets to be constantly mocked rather than also trying to help them in some way. He was never one to do that so his comments were far from welcome or appreciated. He had flown over from Australia to be a guest at the Grand Final and I travelled back to the hotel in the same car with him after that last training session. He could see that I was fighting to hold back the tears but kept goading me as to what was wrong. I left him in no doubt of my feelings and the atmosphere between us moved from frosty to frozen. Inexperienced and downhearted, I alternated between sulking and fuming which, even at that late stage may have cost me what should have been the most important occasion of my life. Back-rower Steve McNamara went down with a mild dose of food poisoning in the dressing room just before the game. He recovered to play but my reaction to the heartache had ruled me out of possible contention as I was already on my way to the player’s lounge to console myself with alcohol. It was a reversion to my old ways, a soft option – the kind I hate now. It also proved why Matt was right; I wasn’t ready for that kind of pressure-cooker environment but his decision probably kicked my career on as much as anything else. It put a fire in my belly to train so hard and play so intensely that should the same option ever arise for a coach, he would have no choice but to pick me; it forced me to raise my own personal bar rather than drink it.

It reignited a stubborn streak that has always been within me; not just the desire to prove others wrong but to challenge myself beyond expectations. Even now, I won’t even do a training run with an iPod because I feel that the music masks the real reasons for being out there. My mum, Denise, tells me that when I was a very young kid, I never cried like some of the others did when it started to snow, I just went out in it; nothing was going to stop me playing. I can remember my auntie gently mocking me when one of my primary school reports said that I should try not to be too competitive. Then when I was eight and really starting to get into the sport, I dislocated my thumb messing around wrestling in the back garden with a mate, a couple of days before a big seven-a-side tournament. I was desperate to play, which helped take my mind off the pain caused by the nurses in casualty pulling my thumb back out, which was awful, and immediately putting it in plaster. Despite the injury, I could still hold a ball and drove my dad, Darryl, nuts begging him to paint it pink so that no one would know and I could continue to be involved with my team, I was that keen. Without that sort of inner drive and desperation to overcome setbacks, I could not have gone on to captain my country – and by rights I shouldn’t have. I was a late developer in the sport; I didn’t even come to the attention of a professional club until I was nineteen. Guys like Paul Sculthorpe and Andy Farrell are groomed for the role from an early age, but I did not play any representative football as a junior. The nearest I got was being on the fringes of the Leeds City Boys teams and, as a young teenager – when a firework badly injured my foot – I nearly gave the game up completely.

A few months after that Old Trafford letdown, the same big-game scenario arose at the Bulls. As I’d promised to myself, I had trained my nuts off over the close-season and began the 2000 campaign really confidently as we qualified for the Challenge Cup final at Murrayfield. This time Matthew told me on the Tuesday beforehand that I would be playing, which, conversely, meant that I had plenty of time to feel nervous – especially as the Leeds Rhinos pack we faced contained three of the toughest, meanest, most respected forwards around: Adrian Morley, Anthony Farrell and Darren Fleary. Playing in that cup decider was the culmination of a long-held dream – just as it would be for so many other kids who have grown up with rugby league. I had touched the famous trophy through the fencing at Wembley when Wigan were doing a lap of honour during their phenomenal run of the late 1980s and early ’90s but I never imagined – even at the false start of my career – that I would get the chance to contest it. I only played for the first, bruising twenty-six minutes that afternoon in the Scottish capital; I was substituted and, although desperate to get back on, Matthew didn’t use me again; but I’d played a part. On the final whistle, my feeling of immense elation was not for me but for my teammate Bernard Dwyer. One of the game’s quiet men, yet a natural leader, he had been a huge positive influence on me with his totally professional outlook, utter dedication and willingness to do the unglamorous toil. It is no coincidence that he subsequently became a prison officer. This was his fifth Challenge Cup final and he had lost the previous four – along with five other major deciders – and it meant so much to me, and the rest of the side, that he could finally bask in some deserved glory. I was lucky – this was my first time and I was a winner.

Just over three years after I felt that Matt Elliott had ruined my ambitions, I was slumped in the accident and emergency department of the Bradford Royal Infirmary. It was during the early hours of the morning and I was ruefully contemplating that I had foolishly wrecked all of the hard work and toil undertaken since that first setback, which had seen me establish myself as a first-team player in a top side and play for my country. Having taken the decision over my chosen profession out of the hands of others and put it in my own, I was now once more – and quite literally this time – on the verge of losing everything. To be a professional sportsman in a code like rugby league – especially among the forwards, where physical imposition and controlled aggression are vital components of your armoury – requires an intense dedication and total focus. Because I perform on the edge, I tend to live on it as well and that has meant occasionally letting off steam with as much zeal as when I have the ball in hand or attempting to make that crunching, intimidatory tackle. Inevitably, perhaps, with sport and alcohol so inextricably linked, that has sometimes meant drinking to excess or, more accurately in the current currency, binge drinking. That is not a justification, and with experience comes increasing realisation of the pitfalls and greater control, but in early March 2003, I looked down at the consequences of my actions fearing the worst.

It was all so needless. We had just played a Challenge Cup tie against Second Division Hunslet which had been switched from their base in the south of Leeds to my favourite haunt, Headingley, to accommodate the expected crowd. Even though they had beaten Super League side Huddersfield Giants in the previous round, we were expected to win at a canter. I was looking forward to the game. It was on the home turf I had worshipped as a boy and there were a number of guys in the opposition ranks who I had socialised with but never got to play against. I’ve been fortunate enough to appear in some huge matches but this wasn’t one of them. Bradford romped to their expected success, hammering the minnows 82-0 and, as arranged, a few of us met up to have a drink afterwards. Somehow that snowballed into a session which saw me arrive home in the early hours rather the worse for wear and, following a beer-fuelled argument, I put my right hand through a plate-glass door, severing the tendons of two fingers, slicing open the flesh and breaking the knuckles. Blood was pumping from the wound but I refused an ambulance, so a taxi was called to hastily take me to casualty where all they could do was dress the ineffective limb and make an appointment for me to come back and see the doctor at eight o’clock that morning.

Having returned home to ponder the guilt-laden significance at about five, wait for the painkillers to kick in and then sleep off the effects of the booze, I missed that appointment. I got there about an hour late and by then my hand had badly swollen up; I couldn’t move it and it began to dawn on me that my cherished career could be over. The nursing staff said that I had to come back later in the afternoon, no matter how much I pleaded with them that I needed to see a doctor straight away because my job was in jeopardy. I sheepishly called the Bradford coach Brian Noble who, from looking out for me in the reserve team and persuading the club to give me a contract when Matthew Elliott had thought better of it, again came to my rescue. He didn’t mince his words about how stupid I had been and then made two decisions which illustrated why he is held in such high regard by the players who work under him. He said he would deal with the Press, releasing a statement from the club that I had broken my hand in the Hunslet game and that I had been sent for an X-ray to cut any speculation that might leak out and take that pressure off. Then he rang his sister, who worked high up in the local NHS and virtually controlled the Bradford hospitals, and she immediately made sure I got to see a specialist straight away. I was incredibly fortunate.

The hand was a complete mess but because the tendons had been severed in a clean and diagonal cut, there was maximum surface area for the surgeon to knit them back together and for them to properly heal. I was booked in for an immediate operation which entailed putting wire rods in my hand to stabilise it. All I kept mulling over was why had I done such a stupid thing. I didn’t feel sorry for myself; it was more the thought that I had let myself and so many other people down – including my teammates, who had shown their belief in me and to whom I owed so much. Under the knife, they also discovered a postage-stamp-sized piece of near-century-old glass and several other shards embedded in my hand, which had all become infected.

Having come through the operation successfully, I had to stay in hospital for five days after the surgery to make sure that the antibiotics were working and although some of the Bradford boys came down to visit, being in that room crystallised my frustration and anger as I went stir crazy. My wife Faye was out at work during the day but I wasn’t good company to be around anyway and, by the time I was released, I was fuming and disgusted with myself. I vowed to repay those who had shielded and kept faith with me and the 2003 season turned out to be one beyond my wildest expectations. The surgeon did a terrific job but his initial diagnosis – after he had put my mind at rest that it wasn’t a career-threatening injury – was that I would be out of action for three months while the tendons repaired. Straight away I decided that it wasn’t going to be that long and I used what turned out to be the seven-week lay-off – the longest I have had to endure – to put in an extra pre-season, even though I couldn’t do anything for a fortnight. Under the guidance of Bulls’ conditioner Martin Clawson, I trained relentlessly with a massive point to prove, put on some weight and came back stronger – defying medical orders to play in the Challenge Cup semi-final and then in the decider in Cardiff, which remains one of my favourite matches of all time.

I’m sure that my mental toughness, above everything else, has enabled me to get to the very top and helped to overcome natural skill deficiencies. It particularly manifested itself during that trying period. Genetically I seem to mend quickly anyway but I also tried to visualise the healing process speeding up and imagined myself to be stronger and fitter, perhaps, than I actually was in a medical sense. I quickly realised in those long, desolate hours of rehab, the ingredients that had been missing from my game and, when I look back, it was that incident that gave me the desire to move up a level again. It has remained a motivation since. The worst thing that could have happened turned into the best over time, and in many ways that is the story of my rugby life.

After that, I played a part in Bradford becoming the first side to achieve a cup and Grand Final double, and while performing with such a sense of purpose and desperation to right my wrong, I ended the campaign with a host of awards, including the highest individual accolade: I was recognised as the coveted ‘Man of Steel’. I was also honoured to be named as the ‘Professional Players’ Player’ and the ‘Rugby League Writers’’ best. There was still one final twist to the saga, however, which proves that in the toughest of arenas, even when you reach the summit, it’s never all fairytales. I’d come back early and was playing with a protective plastic shield around the hand – which got me the nickname ‘The Claw’ – and because I could just about move it, there was an agreement to put off having the metal rods that were keeping my knuckles together removed until the end of the year. After the regular season and our Grand Final triumph, I was included in the Great Britain side to take on the Kangaroos in a three-match Ashes series. Fiercely patriotic, I wasn’t going to pass up the chance of playing for my country in the most demanding, highest-profile matches against the very best. That’s the stage you aspire to through the long, dark days of gym work and physiotherapy. After each Test, though, the hand swelled to ridiculous proportions, although a regular dose of intravenous antibiotics seemed to do the trick to enable me to take the field. When the dressing was finally taken off at the end of the series, gangrene had set in and it took a quickly administered course of antibiotics from GB doctor Chris Brookes to save my hand – just. They tried to remove the rods under a local anaesthetic but the surgeon could not get them to budge. I could feel him rooting about in there, but initially to no great effect. It was nearly a case of making the ultimate sacrifice.

It’s often said that there is a very fine line between madness and genius and in elite professional sport a similar distance divides utter despair and the euphoria of success. The end of the 2007 season marked my tenth anniversary of being a professional rugby league player and I couldn’t have wished for a better way to commemorate it, winning the greatest domestic honour with the club I supported and then leading my country to a first series win in fourteen years. On the Super League front, Leeds finished the season in sensational fashion, eclipsing their rivals to confound a number of doubters, not least within the ranks of our own fans. Getting knocked out of the Challenge Cup early hurt us as a team; we had really wanted to be there to christen the new Wembley. It was that setback, though, which probably worked in our favour, allowing us to play in three-week blocks towards the end of the season. We lost, somewhat surprisingly, at home to Wakefield towards the end of July. The Rhinos players were shocked at the outcome, we got booed off and coach Tony Smith suffered some fearful personal abuse walking down the stand afterwards, which was bang out of order. I had an argument with a bloke in the bar who wanted to have a go about Tony. I told the accuser in no uncertain terms not to come to me on the sly and expect me to bag my boss and that he should either keep his opinions to himself or have the balls to confront the man they were directly aimed at. Faye had to hold me back but I felt aggrieved and justified. We were all down, including the boss, which was unlike him, but the massive thing I’ve learned from our second-rower Jamie Jones-Buchanan – my old mate from Stanningley – is the need to always remain positive. Normally, after a defeat like that, I’d have been incredibly frustrated, annoyed and ranting but, strangely, I was not this time. I went round cajoling the lads, saying: ‘Look, let’s ignore everyone else, they don’t matter. We need to close ranks, concentrate and do this for ourselves because I’m confident we can.’ It was the same conversation I had with Smithy, who was in his final few weeks in the job. I stressed to him how we were in this together and could succeed for one another. It was time to stand up for ourselves and disregard the nonsense that was being churned out. He made a couple of speeches over the next few weeks about how fanatics, not true supporters, are the ones that jeer you and that you have to be prepared to go through the bad times to truly appreciate the good.

We improved from that day and it was one of the reasons behind us going on to win the competition; we took our intense desire as a team to a new level. To be fair to that guy in the bar, once we had achieved our goal and I bumped into him again, he apologised for his earlier outburst. Jamie Thackray was important in those intervening weeks, talking up our chances even though he didn’t get to play in the Grand Final. He wandered around the dressing room from then on geeing everyone up, saying: ‘Are we going to do it, or what?’ It was a sense that hadn’t been at Leeds the year before and proving doubters wrong again figured largely in my psyche. Twelve weeks after being booed off, those same people couldn’t wait to back-slap us.

Super League has become so even that sides can expect to lose one in three of their games now, no matter how good they are, and that trend is set to continue. Supporters need to come to terms with that as the norm and realise that it is the form you get into at the back end of the year that really counts. I’ve never played as consistently well as I did over the final three weeks of the 2007 campaign that encompassed the play-offs. After that Wakefield defeat we had a two-week break and I set myself a target to give everything I had for the final three regular-season rounds and then into the knockout phase. My form improved each week, getting more carries and making further metres, which is generally a sign that things are going well for me. I felt fit and we had another week off before the final stages kicked in, which helped me refocus into a familiar mindset, and things snowballed from there. It’s hard to say if I’ve ever played better than I did in the Grand Final when we put the favourites, St Helens, to the sword. The amount of work I got through was a massive achievement; the stats were pretty impressive on all fronts. It was my sixth time on that stage and going into the match I knew that I had to lead from the front, taking the ball in when others were tired and doing what I do well. I was really pumped up in the week leading up to Old Trafford and Tony primed us perfectly for the contest.

In 2005, when Leeds had last been there as defending champions but lost to their closest rivals, they didn’t take the occasion at Old Trafford seriously enough. I’d witnessed that close up having skippered Bradford to the ultimate triumph that evening, in my final match for them. Tony was smart, he could see what had gone wrong and he changed the routine accordingly. That included an overnight stay, which proved to be another defining factor in our Grand Final success. You need something extra going into the big games; it’s not necessarily greater skill but it’s the channelled emotion and determination you take into them that counts at the final whistle. That is helped by building the occasion up a little bit and the night before, in camp, we had a team meeting. I was nearly in tears for most of it, I was holding them back because I didn’t want to cry in front of the others but it made me even more desperate to win the most sought-after prize alongside that group. We spoke in turn about who we wanted to win for and veteran centre Keith Senior was one of the first up. He said that he was looking to do it for his daughter who got teased a bit at school because she has a kind of cleft palate but it had made her so proud the last time he collected a winner’s ring. Then youngster Carl Ablett told how twelve months before he had been undergoing a full knee reconstruction and was now, after just a handful of games, on the verge of playing in front of over 70,000 fans for the right to be called a champion. Everyone had a compelling reason which we got to share, it was an unbelievable meeting and, with Tony leaving as well, it gave us a massive psychological edge.

Winning the trophy in such a commanding fashion was incredibly important to me, especially after enduring a difficult first season at Leeds when we had underachieved. I had been keyed up to make an early impression with my new club, and did, but threw all my eggs into that basket and then suffered from fatigue towards the end of the 2006 campaign. The fact that I then went on to have a good Tri-Nations tournament skippering Great Britain – culminating in being voted ‘International Forward of the Year’ – led to some murmurings that I was short-changing the Rhinos. Turning those perceptions around a year later was immensely satisfying because so many of the side were from the city and it meant such a lot to the people closest to me, because they all support the team. It felt different, but on a par, with the climax to 2005 when I wanted my last, sign-off appearance with Bradford to be the most memorable. With so much invested at the Bulls spiritually and physically over the years as I was coming through, I wanted to leave on the right note and being able to do so meant everything to me.

Likewise with the Test whitewash against the Kiwis which ended the 2007 season. I feel so lucky to have played with the calibre of player I have at that level. To have put the Great Britain jersey to bed – for me and a lot of the other senior guys – in that fashion just does not get any better; especially after having personally waited seven years for a series win at international level. You only borrow that shirt off its previous incumbents and hold it for the next generation, and we were desperate to do it proud before we relinquished our tenure.

It is only really by sitting down and trying to write a book like this that you can properly reflect on such achievements – not that it means I am contemplating retirement; there are far too many new and exciting challenges on the horizon for that. If you try to evaluate too much while you are still in the midst of everything, it merely becomes self-indulgence. I’ve been fortunate in my career to have had lots of ‘Sky Plus’ moments, where you can programme in and record your favourite bits and keep going back to them. I’ve been involved in a lot of fantastic games and unbelievable nights that I’d like to play in again, if you could do such a thing. Cataloguing them has made me appreciate the huge enjoyment and meaning behind them even more, and how fortunate I am to have played in teams that have been successful. People know about those showpieces because they are well documented, but the events in your life that perhaps you don’t want saving for posterity are the ones that make winning even more special and give the best times their true importance and significance. Writing about the ones I’d like to erase and, often, the despair that surrounds them has been equally important as the glory. Those experiences, as much as anything, have made me who I am today.

2

NO PRETENTIONS OR EXPECTATIONS

From the minute you see some kids playing sport, you can tell they are something special. I was never one of them. I loved being involved, it dominated my early years, but making a living from it or playing at its pinnacle couldn’t have been further from my ambitions. Family life was centred on a typical working-class upbringing; hard work, honesty and loyalty were the watch words around the house. I’ve got two sisters – Amie who is eleven months younger than me and Sally four years my junior – so I spent a lot of time looking out for them from an early age. They are not massive fans of the game, they’ve got their own families and lives but, when they get the chance, they come and support me. Of course we used to argue a lot and as you get older you grow apart, especially if you’re a different gender, but, even so, we remain tight-knit and mates.

Holidays were always spent in either Wales or Cornwall and they were fantastic trips, good times, and the house was always full of cats – I think we had about sixteen at one stage – but from the inside, to me, everything just seemed normal.

I did seem to spend a lot of my early years in hospital and maybe that is why, sometimes, you think that there are forces within you. When I was two, I nearly died. I was in intensive care for quite a while but they never really found out what was wrong with me. The medical people said it was mumps with complications; Mum still reckons that was not the case but I pulled through, even though I was pretty sick. Even before that I knew my way around accident and emergency because as an eleven-month-old I broke one of my legs, slipping down between two parts of the sofa, and I was forever cutting my head open. I’m clumsy anyway but because I always wanted to do things, I naturally just seemed to keep getting into scrapes. It was a regular trip down to St James’s or Leeds General Infirmary for my parents.

Rather than put me off anything to do with physical contact, my stubborn streak just used to make me more determined to carry on. Such determination and dedication is genetic; my granddad on Mum’s side was a professional boxing champion when he was in the navy and a decent footballer – he played for a while for Bournemouth. He was mad keen on the round-ball game but watches rugby league now and wishes he’d had the chance to give it a go. My dad is the hardest-working bloke I know; he has run his own business manufacturing false teeth for as long as I can remember and always made huge sacrifices, doing whatever it took to keep himself above the breadline and the family afloat. There was never much money around and in the days when interest rates soared and nearly sent him over the edge, he was regularly putting in sixteen- or even eighteen-hour days without complaint. He knew it just had to be done and that set a terrific example. Mum possesses the same virtues; she has been unstinting, never griping or moaning about her lot.

I began playing league around the age of four when I brought a letter home from school. Andrew Lightfoot gave it to me and it was from my local club Stanningley saying that they were looking to take on more juniors. Subs were ten pence a week; training began at 6 p.m. on Wednesdays with a match on the Sunday for anyone interested in coming down. That was the start. A lingering memory remains of playing in the park for them, down at the bottom end where there were some council-owned changing rooms. Winters tended to be a lot colder and snowy then and the ritual after games was plunging our iced-up hands under the hot water taps of the big sinks in those freezing huts to try and warm up. It stung your arms like hell but we had to do it to try and get some feeling back and it became something of a dare to see who could keep them under the running water or in the basin the longest. I always enjoyed those days.

School was okay, I went to Stanningley Primary which was a good one and then Intake High Middle School. My results were always quite good but it wasn’t the most conducive environment for a kid like me. I knew how to do just enough to wing it; I could get through without having to hand in too much coursework or, especially, homework. I was pretty sound academically – especially in maths and sciences – but I could have done better if, maybe, I had been pushed, challenged or encouraged more by the teachers. Perhaps that was my problem; I was more interested in having a good time than going that extra mile with my studies. Intake was a strange place for the subjects that I favoured; its renown was in the performing arts. Learning was based around that, which didn’t really suit me. I felt they were more interested in those potential entertainers who had come in from further afield and who wanted to be stars rather than the talent they had on their own doorstep. It was pretty easy to get into trouble and I often did. A lot of us took drama because it was easier to get a good mark in and there was more of a chance to mess about for an hour compared to dance and music, which were the other options. I was never the leading-man type but I didn’t mind a mess about on the drums – although you only got a couple of months’ shot at it before having to make up your mind what course you were doing – but dance was definitely out. It was a bit of a laugh but I never fancied a career as an actor and I could hardly imagine being in a musical.

Some of the friendships made at Intake have endured; Simon Priest and Chris Radford are still good mates, as is Paul McGinity – who, ironically, I had a fight with which saw him expelled. Generally I used to knock around with the older kids, playing football a lot in the park and around the back of the school. That got me selected for the school teams although normally in the age brackets above me; it was not due to the fact that I was any good but more because I always used to get stuck in. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I was a central defender, whose main asset was scything opponents down – finesse was somewhat lacking.

When it came to rugby, Dad coached me most of the way through until I left school. I don’t think he was that interested in the sport until I started playing and he saw it as a chance to get out of the house socially on a regular basis. On many an occasion we used to be running around the old, rickety Stanningley club house after training while he sat at the bar. Unlike now, rugby at amateur level in Leeds seemed to be pretty disorganised. I used to turn up for the trials for the City Boys, and occasionally tagged along as a substitute, but it seemed as though I was never quite good enough to make the starting line-up.

As I progressed through the age groups, Mark Adams and Scott Denevan took over at Stanningley and they had a good set of players to work with and we were quite successful. In the early days, local rivals Milford were the team to beat with the likes of Gavin Brown, James Bunyan, Micky Horner and Guy Adams, who all went on to play professionally, in their ranks. We thought we were pretty sound until we came up against them. My interest waned when I hit my mid-teens and, like a lot of hormonal young men, I didn’t know what I wanted out of life. Standing around with my mates seemed more appealing for a while than making sacrifices for sport. That phase coincided with an accident with a firework. It’s tough sometimes in this country for youngsters when there’s nothing much to do at night and you end up dicking about on street corners getting into petty mischief. A banger, which was being tossed around, landed on my foot and exploded, scorching through my trainers and causing second-degree burns. It hurt like hell and meant that for quite a while I couldn’t wear rugby boots but that was also an excuse I was looking for. My dad was pissed off with me for giving up and it was the first of a number of times when something happened that could have stopped me making it. The group of mates I knocked about with were typical kids who preferred to be outside, trying to avoid getting into scrapes rather than causing them. We never instigated anything malicious – we were better termed as mischievous – but that used to find us in bother every now and then. I wasn’t one to back down from any sort of challenge, which was great grounding for my later life in the game. I had a year out but by the age of sixteen I had regained my enthusiasm and started to enjoy rugby again.

Back at Stanningley I began playing successfully at both under-18 and open-age level, which meant two games a weekend. John Darby was the coach and the life and soul of the club. Sadly, he has now passed away but one of his legacies was to change my name. I arrived as James and almost immediately he started calling me Jamie. I mentioned to him that it was James and he said: ‘Okay, Jamie, off you go.’

It’s almost impossible to put an exact time on when it first dawned on me that I might be able to make a career out of the sport. I just enjoyed being a youth in the men’s second team and the lads involved seemed to think I was making a contribution. At the same time I was doing well for the under-18s, we got to a cup final and I managed to claim the Man of the Match award even though we lost. I received a similar accolade when the senior side won a sevens tournament and things seemed to be progressing. I was happy to play anywhere; I guess I was as keen as I was versatile, so they threw me in at second-row, scrum-half, wherever. I was skinny, had a bit of speed and I loved it. The set-up really suited me; building up for games, having a great time with a good bunch of lads and then, invariably, going out on the piss after matches together – Stanningley was a great club for that. If there hadn’t then been scouts sniffing around, I would have continued playing at amateur level.

I’ve never really suffered from nerves before a game; my only real worry when I was younger was to play well and not let my teammates down rather than be too concerned with the opposition or the stage. More than anything I had to overcome shyness and the prospect that, if there was a big crowd, people would laugh at me if I messed up. Nowadays, that is not a factor because I know that I have done everything possible to prepare thoroughly for a game with a routine that doesn’t alter or vary too much. If I can do my job well, I know that it will help the team and I’ve never lost the anticipatory thrill of getting out there and mucking in. Such a philosophy is the basis of my captaincy, particularly for Great Britain. I’m not necessarily one for Churchillian speeches; it’s more about stressing to the lads to do it for each other because we are all good blokes, and making sure the game plan is set and the emotions are intact. ‘Play well for your mate, yourself and above all enjoy it’ has always been my mantra. What you are good at, you revel in doing well, whether it is kick-chasing like Jamie Jones-Buchanan, smashing people in the manner that Gareth Ellis does so well or taking the big hits that I do every now and then. The sum of those parts, done to be the best of a player’s ability usually means a team will win; there’s no great mega-science or mystique about it.

I seem to have always had an instinctive timing and technique on defence. Whenever we did tackling practice, even as an under-nine, and were trying ten repetitions, nobody wanted to do it with me because they said I hurt them too much. That’s always been in me, as has wanting to beat someone in whatever task I’ve faced. They were ethics which were reinforced by what Dad constantly drilled into me; he had me practicing all the time. Progress was helped by a growth spurt when I was around seventeen, which was important in the way I wanted to play. I’ve always had a wiry kind of strength but the added height enhanced my self-confidence. I wasn’t one of those young kids I sometimes came up against who already sported a beard; I was a late developer on a number of fronts. Solving another medical condition about that time was another significant turning point, when I finally went to be fitted for contact lenses. I really couldn’t see, I’m very short-sighted and even though I was thoroughly enjoying my rugby, that visit to the opticians improved it immensely. I started chasing the ball rather than carrier bags flying across the pitch, as Matt Elliott used to remind me. The first time he came down to see me play at Stanningley before the lenses were inserted, he saw this eager kid often running in the wrong direction. Suddenly, from barely being able to distinguish teammates or where the try line was, I could appreciate what was going on around me, my handling skills increased out of sight – excuse the pun – which was another great confidence boost and I never looked back.

I had wanted to stay on at school and take my ‘A’ levels but, in hindsight, to have done that I should really have gone to college; that would have suited me better. The school regime wasn’t for me; I felt that that they treated the older pupils too childishly and I wanted to go out socialising. I left and got a job working full-time loading parcels for DHL and had some ambitions to go through the ranks there on the management and logistics side.

Soon after I started in the depot, I was asked to attend a trial at Wakefield Trinity. I played a couple of academy matches for them against Hull and then, ironically, Bradford. In that match they put me in at prop and I must have been the skinniest one ever to take the field. Peter Tunks, the former Aussie Test front-rower who had played for Leeds, was the chief executive at Belle Vue at the time and although he said he wanted to sign me for Trinity, the money was ridiculously low. Bradford said they were interested in the summer of 1996, just as Super League started but I had very little self belief in my ability to play at that level. My dad must have been sick of making excuses for me failing to show up for training but eventually I overcame my doubts and went up to Odsal. I didn’t want to end up like one of those guys who sat around the pub telling no one in particular: ‘I could have had trials or done that or achieved this’. I made up my mind to go and they threw me in against Castleford who were a top academy side at the time. Determined to make the most of the chance, I must have played pretty well because I got the Man of the Match award. That, though, left me with a problem. The Bulls said they were going to sign me to a professional contract so I left my job but it took them three months to come up with a firm offer.

In the interim, to keep body and soul together while I was in limbo, I was forced to get employment with a roofing company working twelve-hour shifts for twenty quid a day. Dave and Pete Rennie took me on to do the labouring and it was just really tough graft. The work didn’t faze me but it was hard times, the kind which make you appreciate what you do eventually get that much more. We were on site at seven in the morning and I’ve never forgotten how exhausting and often inhospitable it was. Occasionally, even now, you need to draw on inspiration from elsewhere when it gets tough on the rugby field or in training and when that happens I remember and appreciate those days. It’s often said that if you find a job that you enjoy, then you never do a day’s work but that’s bullshit. I love playing professional sport but there are times when it feels like the hardest work imaginable and that’s when I think back that I could be on top of someone’s house lugging pieces of wood instead. There were no inklings of being Great Britain captain when I was slung in the back of a van among various assorted materials and tools. Not every day is a great day, whatever job you do.

From the minute I saw it, I was impressed with the Bradford set-up, which had undergone something of a transformation with the advent of Super League and summer rugby. Even though I had supported Leeds from as far back as I could remember, and spent many an afternoon following the likes of Ellery Hanley – who had initially made his name at Odsal – from the Headingley terraces, playing for their great rivals was never an issue. Leeds never approached me throughout my junior days and if you’ve gone past the age of sixteen without being spotted then you rarely get swept up. I’ve always felt that although the scholarship systems and apprenticeships now provide an excellent grounding for a youngster, there should always be safety net for those who miss out in their formative years. Some young, talented players look superb before they get into open age and are then found out; Adam Hughes, who I played with in the Leeds City Boys squads, would be a prime example. Nevertheless, I was convinced that the Bradford deal was going to fall through so I carried on doing full shifts of manual work and then going training. The no-nonsense, deep-thinking, hard-nosed Aussie Brian Smith was the Bulls’ revolutionary head coach and one evening, because his son Rohan was playing at Stanningley, he gave me a lift home. I was nineteen at the time and although I can’t quite remember what he said, I know it was one of the most nerve-racking journeys I’ve ever taken – and that only one of us was doing any of the talking. I was seriously intimidated.

Eventually, going full-time at the Bulls was sorted out but it was an incredibly hard transition. The money I was earning was less than being employed and it was difficult to adjust, partly because being a young professional was such a new concept. In many ways, the first batch of signings were like guinea pigs, we were expected to be fully switched on to a life in the sport but we were entrenched in an amateur environment that included seeing your mates and going out for a good time, which invariably involved drinking. We had no mentors and it was never really made clear what was expected of us. Looking back, I don’t know if I ever really got to grips with it. It was very long hours; we trained in the mornings, would go out to work with schools in the afternoons and then come back to train again in the evening. I can see why a lot of the lads who were around at that time fell by the wayside. My early career ran almost parallel with another of my Stanningley teammates, Craig Horne. He went up to Bradford and then on to Featherstone and ended up playing in France and we lost touch. He used to fight like mad with his brother Mark, they were always at each other, but Craig was a pretty determined winger and even though it didn’t work out for him at Odsal, he made a go of it at Rovers, did a good job for them and was around when I later went over there on loan. That helped me and we used to travel together to Post Office Road. The only other one from our age group at Stanningley to spend a significant time in the professional ranks was Andy Bastow, who was one of the better players in the side. He got a run out with Wakefield, signed for Featherstone and then ended up at Hunslet. It would have been good to play against him but the only chance would have been in that ill-fated cup clash at Headingley which was the precursor to the drama with my hand, only he was out injured at the time. Another Bramley lad, Michael Banks and I came through the ranks together at Stanningley and we were almost inseparable. We signed on the Bradford scholarship scheme at the same time and the great bonus for me was that he had transport and used to give me lifts to training and just about everywhere else. He made one appearance for the Bulls first team in 1998 and eventually ended up playing back at our first club.

My roots have always been incredibly important to me, which is why I am only too pleased to try and help out with the coaching and I have an involvement back at Coal Hill Drive now. Brian McDermott said to me recently that when you have been through what we have as professional players, it changes you. I’m not the same as the blokes I used to knock about with at school, you can’t help that. Top-level rugby league makes you grow as a person and a man, and although it might sound grandiose, those experiences – even though it is through sport – make you look at life differently. I’ve done some things that not many others have and that’s not arrogance, it’s just stating facts. But I come from the kind of background and a code that if you get above yourself you get shot down, and I like to stay close to those values. I don’t just play the sport – I love it, and I’d go back and run around in amateur rugby league tomorrow if that was the only option. What I’ve achieved should show any aspiring junior what can happen. I’m fortunate that I was brought up within the middle of a good, supportive family, with a great set of friends and in Yorkshire. I have an undying love of the place and the people, who have few airs and graces. Rugby has taught me to be open-minded and I’ve been able to travel to other places and appreciate different cultures as a result of it but, no two ways about it, my favourite places are still among the Broad Acres.